Functional Ecology ( IF 4.6 ) Pub Date : 2022-08-20 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2435.14168 Natalie K. Rideout 1 , Zacchaeus G. Compson 2, 3 , Wendy A. Monk 4 , Meghann R. Bruce 5 , Mehrdad Hajibabaei 6 , Teresita M. Porter 6 , Michael T. G. Wright 6 , Donald J. Baird 2

|

1 INTRODUCTION

In dynamic ecosystems, the ability of communities to remain resilient to natural and human-induced disturbances and support vital ecosystem functions is degraded by biodiversity loss (Tilman & Lehman, 2001). Biodiversity, which reflects taxonomic and functional variety, provides an ‘insurance policy’, whereby many species exhibit a range of responses to varying disturbances. Biodiversity critically also includes redundancy (or niche overlap) ensuring that ecosystem functions are maintained even as species are lost (Díaz & Cabido, 2001). In a review of 100 studies, Srivastava and Vellend (2005) found that 71% reported enhanced rates of ecosystem function with increased biodiversity. Defined by Pacala and Kinzig (2002), ecosystem function describes an ecosystem's stability, its ability to maintain energy fluxes (e.g. production and decomposition) and its stocks of energy and biomass (e.g. Loreau et al., 2002; Tilman et al., 2006). The maintenance of these functions is an indication of a healthy ecosystem. While ‘ecosystem health’ is often an undefined term in ecological literature, even considered controversial by some, it is defined here after Constanza and Mageau (1999) as an ‘ability to maintain structure and function over time in the face of external stress’. In floodplain wetlands, vital functions include decomposition, which link terrestrial and aquatic food webs (Langhans et al., 2006), and primary production, where aquatic macrophyte and periphyton communities generate biomass to support the base of food webs (McCormick & Stevenson, 1998).

The link between biodiversity and ecosystem function (BEF) has been recognized by ecologists for decades (Tilman & Lehman, 2001); mechanisms behind this link are the subject of active research, focusing chiefly on functional traits (Díaz & Cabido, 2001). Traits are defined as the ‘morphological, physiological or behavioural characteristics of a species that describe a species' physical characteristics, functional role in an ecosystem, or its ecological niche’ (Baird et al., 2008). The shift in focus from taxonomy-based biodiversity to traits-based studies is important in that traits allow ecologists to compare across broader scales, where species may be interchangeable, but traits are retained, and account for species that may fill several niches depending on their life stage (Baird et al., 2011). Trait-based ecology also encompasses the fact that abiotic variables act as environmental filters primarily for traits, only secondarily filtering for the taxa that hold those traits (Bonada et al., 2007).

From a biomonitoring perspective, traits influencing key ecosystem functions are critical to conserve (Rosenfeld, 2002); equally important is the maintenance of functional redundancy to sustain resilience to future disturbances (Díaz et al., 2013). Ecosystem vulnerability is strongly dependent on the phylogenetic similarity of groups that provide certain functions (through taxon effect traits), as environmental filtering for response traits can eradicate entire lineages with similar functional roles (Rosenfeld, 2002; Trios et al., 2014). In fact, it is response traits—those that influence a species' ability to colonize and thrive in an environment (and thus, its fitness)—that are subject to natural selection (Rosenfeld, 2002). Trios et al. (2014) proposed that under high disturbance, communities are dominated by phylogenetically similar species, while communities with low levels of disturbance tend to be more distantly related, reducing competition through niche complementarity, resulting in more efficient use of available resources (Hooper et al., 2002). This theory assumes that natural selection of species through environmental filtering of response traits will result in communities with similar sets of traits, and therefore lineages, that are more capable of withstanding disturbance (Trios et al., 2014). While much research focusing on the link between traits and BEF has centred on trophic relationships, more recently, Maureaud et al. (2020) have emphasized the need to consider wider trait responses to multiple ecosystem functions, in real-world situations with complex, varying habitat conditions.

Following from the above, as functionally diverse ecosystems with significant spatial and seasonal habitat disturbances, river floodplains provide an excellent proving ground for traits-based ecological theory, as they support mosaics of habitat patches at different successional stages with varying degrees of hydrological connectivity to the main channel (Bayley & Guimond, 2008; Tockner et al., 2010). Despite the rise in traits-based science, taxonomic resolution has imposed limitations (Vieira et al., 2006), especially in taxonomically rich floodplain wetland ecosystems (e.g. Funk et al., 2017), which are understudied compared to riverine counterparts (Tockner et al., 2010). DNA metabarcoding via high-throughput sequencing provides a powerful tool to characterize community composition in unprecedented detail (Bush et al., 2019; Gibson et al., 2015), delivering sufficient taxonomic detail to study how environmental filters affect invertebrate traits, and the consequences for maintenance of healthy ecosystem function.

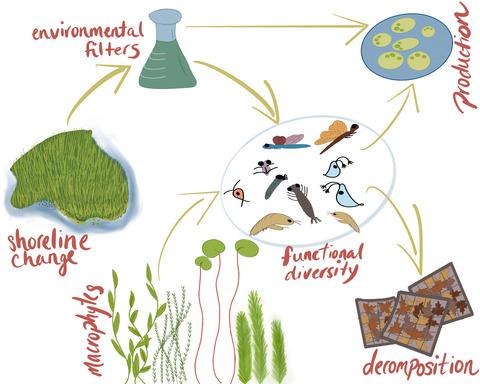

The objective of this study was to elucidate the drivers of macroinvertebrate community structure and associated wetland ecosystem function. This was done by (1) using a structural equation model (SEM) framework to quantify the linkages among environmental filters, macroinvertebrate functional diversity and ecosystem function, and test the specific hypotheses outlined in Table 2 and (2) using Threshold Indicator Taxa ANalysis (TITAN2) to compare how taxa and traits respond to gradients of function and environmental filtering. These are critical issues to address, as they can provide insights into how to improve wetland protection, and how to prioritize wetland restoration actions to restore healthy floodplain ecosystems. Maintaining diverse, functionally redundant communities that are resilient to future disturbances is particularly important in productive, service-delivering ecosystems such as floodplain wetlands, which have been, and continue to be, under threat of human development and climate change.

中文翻译:

大型无脊椎动物性状的环境过滤影响大型河流泛滥平原的生态系统功能

1 简介

在动态生态系统中,社区保持对自然和人为干扰的弹性并支持重要生态系统功能的能力因生物多样性丧失而降低(Tilman & Lehman, 2001)。反映分类和功能多样性的生物多样性提供了一种“保险政策”,许多物种对不同的干扰表现出一系列反应。至关重要的是,生物多样性还包括冗余(或生态位重叠),确保即使物种消失也能维持生态系统功能(Díaz & Cabido, 2001)。在对 100 项研究的回顾中,Srivastava 和 Vellend(2005 年)发现,71% 的人报告说,随着生物多样性的增加,生态系统功能的比率会提高。由 Pacala 和 Kinzig 定义(2002 年)),生态系统功能描述了生态系统的稳定性、其维持能量通量(例如生产和分解)的能力以及其能量和生物质存量(例如 Loreau 等人, 2002 年;Tilman 等人, 2006 年)。这些功能的维持是健康生态系统的标志。虽然“生态系统健康”在生态学文献中通常是一个未定义的术语,甚至被一些人认为是有争议的,但它在 Constanza 和 Mageau ( 1999 ) 之后被定义为“在面对外部压力时保持结构和功能的能力”。在洪泛区湿地,重要功能包括分解,将陆地和水生食物网联系起来(Langhans 等, 2006) 和初级生产,其中水生大型植物和附生植物群落产生生物量以支持食物网的基础(McCormick & Stevenson, 1998 年)。

几十年来,生态学家已经认识到生物多样性和生态系统功能 (BEF) 之间的联系(Tilman & Lehman, 2001);这种联系背后的机制是积极研究的主题,主要关注功能特征(Díaz & Cabido, 2001)。性状被定义为“一个物种的形态、生理或行为特征,描述了一个物种的物理特征、生态系统中的功能作用或其生态位”(Baird 等, 2008)。将重点从基于分类的生物多样性转移到基于特征的研究很重要,因为特征允许生态学家在更广泛的范围内进行比较,其中物种可能是可互换的,但特征得以保留,并解释了可能填补多个生态位的物种,具体取决于它们生命阶段(Baird 等人, 2011 年)。基于特征的生态学还包括这样一个事实,即非生物变量主要作为特征的环境过滤器,仅次要过滤具有这些特征的分类群(Bonada et al., 2007)。

从生物监测的角度来看,影响关键生态系统功能的特征对于保护至关重要(Rosenfeld, 2002 年);同样重要的是保持功能冗余以维持对未来干扰的恢复能力(Díaz 等人, 2013 年)。生态系统脆弱性强烈依赖于提供某些功能的群体的系统发育相似性(通过分类单元效应特征),因为对响应特征的环境过滤可以根除具有相似功能角色的整个谱系(Rosenfeld, 2002;Trios 等, 2014)。事实上,受自然选择影响的是反应性状——那些影响物种在环境中定殖和繁衍的能力(从而影响其适应性)的特性(Rosenfeld, 2002 年)。三重奏等。( 2014 ) 提出,在高干扰下,群落以系统发育相似的物种为主,而低干扰的群落往往关系更远,通过生态位互补性减少竞争,从而更有效地利用可用资源 (Hooper et al. , 2002 年)。该理论假设通过对响应特征的环境过滤来自然选择物种将导致群落具有相似的特征集,因此谱系更能承受干扰(Trios et al., 2014)。虽然许多关注性状和 BEF 之间联系的研究都集中在营养关系上,但最近,Maureaud 等人。( 2020) 强调需要考虑在具有复杂多变栖息地条件的现实情况下对多种生态系统功能的更广泛性状响应。

综上所述,作为功能多样的生态系统,具有显着的空间和季节性栖息地扰动,河流漫滩为基于特征的生态理论提供了极好的试验场,因为它们支持不同演替阶段的栖息地斑块镶嵌,具有不同程度的水文连通性。主渠道(Bayley 和 Guimond, 2008 年;Tockner 等人, 2010 年)。尽管基于特征的科学有所增加,但分类学的分辨率已经施加了限制(Vieira 等人, 2006 年),特别是在分类学丰富的洪泛平原湿地生态系统(例如 Funk 等人, 2017 年),与河流对应物相比,这些生态系统研究不足(Tockner 等人)等, 2010)。通过高通量测序进行 DNA 元条形码编码提供了一个强大的工具,可以以前所未有的细节描述群落组成(Bush 等人, 2019 年;Gibson 等人, 2015 年),提供足够的分类学细节来研究环境过滤器如何影响无脊椎动物的性状及其后果用于维持健康的生态系统功能。

本研究的目的是阐明大型无脊椎动物群落结构和相关湿地生态系统功能的驱动因素。这是通过 (1) 使用结构方程模型 (SEM) 框架来量化环境过滤器、大型无脊椎动物功能多样性和生态系统功能之间的联系,并测试表 2 中概述的特定假设和 (2) 使用阈值指标分类分析 ( TITAN2) 比较分类群和性状如何响应功能梯度和环境过滤。这些是需要解决的关键问题,因为它们可以提供有关如何改善湿地保护以及如何优先考虑湿地恢复行动以恢复健康的洪泛区生态系统的见解。保持多样化,

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号