Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.5 ) Pub Date : 2022-06-10 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.13946 Rafaella Canessa 1, 2 , Liesbeth van den Brink 2 , Monica B. Berdugo 1 , Stephan Hättenschwiler 3 , Rodrigo S. Rios 4, 5 , Alfredo Saldaña 6 , Katja Tielbörger 2 , Maaike Y. Bader 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Litter decomposition, that is, the breakdown of organic matter and the release of its components in mineral forms (e.g. CO2) or as organic molecules, is a fundamental process in biogeochemical cycles and plays a central role in ecosystem functioning (Berg & McClaugherty, 2003). Litter inputs to ecosystems vary tremendously as a function of the identity and diversity of plant species, as species differ widely in their litter phenology, chemistry and morphology (Cornwell et al., 2008). This diversity is thought to influence litter decomposition (Hättenschwiler et al., 2005; Kou et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Litter diversity can affect decomposition positively (faster decomposition of litter mixtures than predicted from single litter species decomposition) or negatively (slower decomposition of litter mixtures), although overall non-additive effects (decomposition of mixtures equals the mean of its parts) seem to prevail (Gartner & Cardon, 2004; Kou et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). These responses to litter diversity may depend on the nature of the mixtures, on environmental conditions (e.g. climate or soil properties) and on decomposition stages (Handa et al., 2014; Kou et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Moreover, the multiple mechanisms that can drive positive or negative litter mixture effects remain difficult to determine (Hättenschwiler et al., 2005). Previous studies have shown that the diversity in initial litter quality (i.e. functional diversity) may drive litter mixture effects in predictable ways (Barantal et al., 2014; Handa et al., 2014), because the mechanisms behind these effects are driven by specific litter traits (Barantal et al., 2014; Handa et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020). However, it still remains largely unclear which traits or combinations of traits are the most relevant.

While several traits have been proposed to drive litter decomposition (Canessa et al., 2021; Makkonen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2008), only a few of them may be particularly important in determining litter mixture effects. Nutrients such as nitrogen, potassium, calcium or magnesium can be actively transferred among different litter types within mixtures by micro-organisms (Bonanomi et al., 2014; Briones & Ineson, 1996; Handa et al., 2014; Schimel & Hättenschwiler, 2007). Since such nutrients are frequently limiting resources for micro-organisms, transfers between litter types can help to optimize resource availability for decomposers. As a result, the relative mixing effects may be stronger for slowly than for more rapidly decomposing litter types within a mixture (Liu et al., 2020; Salamanca et al., 1998), leading to an overall positive effect, that is, faster decomposition in mixtures than predicted from their respective single-species litter (Hättenschwiler et al., 2005; Lummer et al., 2012).

Apart from transferable nutrients, secondary compounds may represent another relevant group of litter traits determining litter mixture effects (e.g. polyphenols; Hättenschwiler et al., 2005). The presence of toxic or recalcitrant compounds in one litter type may inhibit microbial activity, affecting other litter types and decreasing overall decomposition (McArthur et al., 1994), consequently producing negative mixture effects (i.e. slower decomposition than predicted). This process appears to occur principally via passive transfer (e.g. leaching, water films) of inhibitory compounds (Gessner et al., 2010). Hence, any expected correlation between functional diversity and litter mixture effects may be related to relatively mobile nutrients and/or secondary compounds from specific litter types within the mixture (Gessner et al., 2010). As these trait-related mixture effects can be positive or negative, the net effect on the overall litter mixture may be zero despite the fact that specific litter types may decompose at different rates within the mixture compared to when they decompose singly. Because different mechanisms associated with distinct litter traits may be at play simultaneously within litter mixtures, it is important to characterize multiple traits to be able to disentangle their relative role in litter mixture effects (Hoorens et al., 2003). In fact, it seems that no single trait or group of traits is sufficient to reliably predict litter mixture effects (Porre et al., 2020). However, very few studies explicitly include multiple traits to study litter mixture effects, which makes it difficult to understand litter mixture effects and their drivers.

Litter mixture effects seem to differ among ecosystems. Positive effects of litter mixtures on decomposition have been reported in grasslands (Liu et al., 2020; Scherer-Lorenzen, 2008) and tree plantations (Alberti et al., 2017), where a higher functional diversity in physical and chemical traits favoured microbial activity. In natural forests, where most of litter diversity studies have been developed, null, negative or positive mixture effects have been reported (Barantal et al., 2014; Gartner & Cardon, 2004; Gripp et al., 2018; Handa et al., 2014; Leppert et al., 2017), with notable differences among climate zones. This suggests that, beyond litter quality differences, the environment (i.e. climate) and decomposer communities play an important role in litter mixture effects (Zhou et al., 2020). Overall, in temperate and subtropical forests positive effects dominate, while in boreal forests and alpine shrublands null and negative effects are more common (Kou et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). This may suggest that relatively high and mild temperatures favour positive mixture effects, whereas low temperatures with more constrained soil decomposer activity rather lead to null or negative effects (Liu et al., 2020). Perhaps, at low temperatures environmental constraints override the biotic responses that support positive mixture effects. Alternatively, where litter traits associated with more severe environmental conditions, such as secondary compounds, become more frequent, negative mixture effects may prevail. Although it is not well studied in the literature why unfavourable climate conditions could promote negative effects (Liu et al., 2020), it seems reasonable to consider that, when an active nutrient transfer does not occur, other mechanisms, such as shared effects of inhibitory compounds, can become dominant. Interestingly, however, recent meta-analyses indicate no clear relationship between litter mixture effects and temperature (Liu et al., 2020; Porre et al., 2020), and the question about how environmental constraints may modulate litter mixture effects remains poorly explored. Limitations in humidity may be even more important than temperature for the determination of litter mixture effects. Indeed, deserts and semi-arid areas are known to impose particularly strong limitations on decomposer communities via low moisture availability (Jones et al., 2018; Moskwa et al., 2020). However, very few studies address litter diversity effects on decomposition in these ecosystems (e.g. Ndagurwa et al., 2020). This lack of data across ecosystems impedes an assessment of the effects of environmental parameters and their interaction with litter traits on litter mixture effects (Porre et al., 2020).

To understand how and why litter mixture effects on decomposition differ among ecosystems, studies that concurrently investigate mixture effects across large climatic gradients including contrasting environmental conditions are urgently needed. Yet, such experimental studies are rare (but see Zhou et al., 2020) and meta-analyses are biased towards temperate ecosystems (Kou et al., 2020; Porre et al., 2020). The comparison of litter mixture effects across large environmental gradients is challenging, because of strong differences in litter decomposition rates among sites (Cornwell et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008), with potentially variable litter mixture effects in different decomposition stages (Santonja et al., 2019). Specifically, mixture effects seem to decrease with time (Butenschoen et al., 2014; Kou et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2013), probably due to converging litter quality during decomposition, leading to a weaker potential for mixture effects in late decomposition stages (Canessa et al., 2021; Currie et al., 2010).

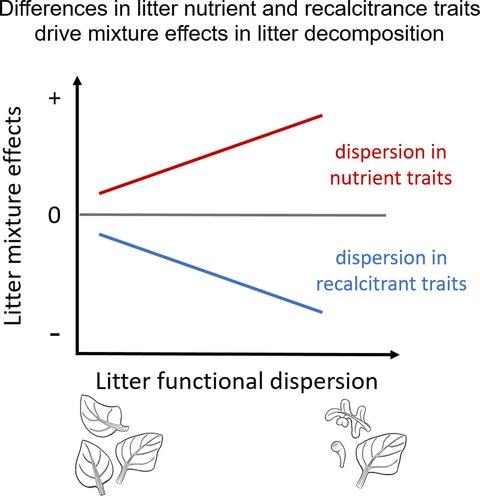

Here, we present a field experiment that ran for almost 2 years to unravel the effects of two aspects of litter diversity, species richness and functional dispersion (FDis, a measure of functional richness and divergence), on litter decomposition along a pronounced climate and vegetation gradient ranging from the Atacama Desert (26°S) to humid temperate forests (38°S) in Chile. Using different sets of functional traits to calculate FDis, we investigated whether nutrient-related traits associated with resource transfer among litter types, or secondary compounds associated with inhibiting decomposition are important for non-additive litter mixture effects (Figure 1). Specifically, we hypothesized the following: (1) Positive non-additive litter mixing effects are more frequent in ecosystems with less moisture constraints and decrease with increasing moisture constraints, eventually becoming negative in the driest ecosystems. (2) Positive mixing effects become stronger with increasing litter functional diversity (FDis) based on nutrient traits, and negative mixing effects become stronger with increasing litter FDis based on secondary compounds (Figure 1). (3) Non-additive litter mixing effects are more frequent during the early stages of decomposition, when trait differences driving non-additive effects are still most pronounced.

中文翻译:

性状功能多样性解释了气候梯度干旱末端对凋落物分解的混合效应

1 简介

凋落物分解,即有机物质的分解及其成分以矿物形式(例如 CO 2)或作为有机分子的形式释放,是生物地球化学循环中的一个基本过程,在生态系统功能中起着核心作用(Berg & McClaugherty, 2003 年)。生态系统的凋落物输入因植物物种的特性和多样性而有很大差异,因为物种的凋落物物候、化学和形态差异很大(Cornwell 等人, 2008 年)。这种多样性被认为会影响垃圾分解(Hättenschwiler 等人, 2005 年;Kou 等人, 2020 年;Liu 等人, 2020 年))。凋落物多样性可以对分解产生积极的影响(凋落物混合物的分解速度比单一凋落物物种分解预测的更快)或消极的(凋落物混合物的分解速度更慢),尽管总体非累加效应(混合物的分解等于其部分的平均值)似乎占主导地位(Gartner & Cardon, 2004 年;Kou 等人, 2020 年;Liu 等人, 2020 年)。这些对凋落物多样性的反应可能取决于混合物的性质、环境条件(例如气候或土壤特性)和分解阶段(Handa 等人, 2014 年;Kou 等人, 2020 年;Liu 等人, 2020 年))。此外,驱动垃圾混合效应的多种机制仍然难以确定(Hättenschwiler 等人, 2005 年)。先前的研究表明,初始垫料质量的多样性(即功能多样性)可能以可预测的方式驱动垫料混合效应(Barantal 等人, 2014 年;Handa 等人, 2014 年),因为这些影响背后的机制是由特定的垫料特征(Barantal 等人, 2014 年;Handa 等人, 2014 年;Liu 等人, 2020 年)。然而,在很大程度上仍不清楚哪些特征或特征组合是最相关的。

虽然已经提出了几个特征来驱动凋落物分解(Canessa 等人, 2021 年;Makkonen 等人, 2012 年;Zhang 等人, 2008 年),但其中只有少数可能对确定凋落物混合效应特别重要。氮、钾、钙或镁等营养物质可以通过微生物在混合物中的不同垫料类型之间积极转移(Bonanomi 等人, 2014 年;Briones 和 Ineson, 1996 年;Handa 等人, 2014 年;Schimel 和 Hättenschwiler, 2007 年))。由于此类营养物质经常限制微生物的资源,因此垫料类型之间的转移有助于优化分解者的资源可用性。因此,在混合物中,慢速分解的相对混合效果可能比分解速度更快的垫料类型更强(Liu 等人, 2020 年;Salamanca 等人, 1998 年),从而产生整体积极影响,即更快混合物中的分解比从它们各自的单一物种垃圾中预测的要高(Hättenschwiler 等人, 2005 年;Lummer 等人, 2012 年)。

除了可转移的养分,次生化合物可能代表另一组决定垫料混合效应的相关垫料特征(例如多酚;Hättenschwiler 等人, 2005 年)。一种垫料类型中有毒或顽固化合物的存在可能会抑制微生物活动,影响其他垫料类型并降低整体分解(McArthur 等人, 1994 年),从而产生负面的混合效应(即分解比预期慢)。这一过程似乎主要通过抑制性化合物的被动转移(例如浸出、水膜)发生(Gessner 等, 2010)。因此,功能多样性和垫料混合物效应之间的任何预期相关性都可能与混合物中特定垫料类型的相对流动的营养物质和/或次生化合物有关(Gessner 等人, 2010 年)。由于这些与性状相关的混合效应可能是正面的或负面的,因此对整个垫料混合物的净影响可能为零,尽管与单独分解时相比,特定垫料类型在混合物中的分解速率可能不同。由于与不同垫料特征相关的不同机制可能在垫料混合物中同时发挥作用,因此表征多个性状以便能够解开它们在垫料混合物效应中的相对作用非常重要(Hoorens 等, 2003)。事实上,似乎没有任何单一性状或一组性状足以可靠地预测垫料混合效应(Porre 等人, 2020 年)。然而,很少有研究明确包括研究垃圾混合效应的多个特征,这使得很难理解垃圾混合效应及其驱动因素。

凋落物混合效应似乎在生态系统之间有所不同。在草地(Liu 等人, 2020 年;Scherer-Lorenzen, 2008 年)和人工林(Alberti 等人, 2017 年)中,已经报道了凋落物混合物对分解的积极影响 ,其中物理和化学性状的更高功能多样性有利于微生物活动。在大多数枯枝落叶多样性研究已经开展的天然林中,已经报告了无效、负面或正面的混合效应(Barantal 等人, 2014 年;Gartner 和 Cardon, 2004 年;Gripp 等人, 2018 年;Handa 等人, 2014 年;莱珀特等人, 2017 年),气候带之间存在显着差异。这表明,除了凋落物质量差异之外,环境(即气候)和分解者群落在凋落物混合效应中发挥着重要作用(Zhou et al., 2020)。总体而言,在温带和亚热带森林中,正面效应占主导地位,而在北方森林和高山灌木丛中,无效和负面效应更为常见(Kou 等人, 2020 年;Liu 等人, 2020 年)。这可能表明,相对较高和温和的温度有利于积极的混合效应,而较低的温度和土壤分解剂的活性受到更多限制,反而会导致无效或负面影响(Liu et al., 2020)。也许,在低温下,环境限制会压倒支持积极混合效应的生物反应。或者,当与更恶劣的环境条件相关的垫料特征(例如次生化合物)变得更加频繁时,负面的混合效应可能会占上风。尽管在文献中没有很好地研究为什么不利的气候条件会促进负面影响(Liu 等人, 2020 年),但似乎有理由认为,当没有发生积极的养分转移时,其他机制,例如抑制性化合物,可以成为主导。然而,有趣的是,最近的荟萃分析表明垫料混合物效应与温度之间没有明确的关系(Liu 等人, 2020 年;Porre 等人, 2020 年)),关于环境约束如何调节垃圾混合物效应的问题仍然没有得到很好的探索。对于确定垫料混合物的影响,湿度的限制可能比温度更重要。事实上,众所周知,沙漠和半干旱地区通过低水分可用性对分解者群落施加了特别强烈的限制(Jones 等人, 2018 年;Moskwa 等人, 2020 年)。然而,很少有研究涉及垃圾多样性对这些生态系统分解的影响(例如 Ndagurwa 等人, 2020 年)。整个生态系统数据的缺乏阻碍了评估环境参数的影响及其与凋落物特征的相互作用对凋落物混合效应的影响(Porre 等人, 2020 年)。

为了了解不同生态系统中垃圾混合物对分解的影响如何以及为何不同,迫切需要同时研究大气候梯度(包括对比环境条件)中的混合物影响的研究。然而,此类实验研究很少见(但参见 Zhou 等人, 2020 年),并且荟萃分析偏向于温带生态系统(Kou 等人, 2020 年;Porre 等人, 2020 年)。由于不同地点之间的凋落物分解率存在很大差异,因此比较大环境梯度下的凋落物混合物效应具有挑战性(Cornwell 等人, 2008 年;Zhang 等人, 2008 年)),在不同的分解阶段可能会产生可变的垃圾混合物效应(Santonja 等人, 2019 年)。具体而言,混合效应似乎随着时间的推移而降低(Butenschoen 等人, 2014 年;Kou 等人, 2020 年;Wu 等人, 2013 年),这可能是由于分解过程中垫料质量的收敛,导致混合效应的潜力较弱后期分解阶段(Canessa 等人, 2021 年;Currie 等人, 2010 年)。

在这里,我们进行了一项为期近 2 年的田间实验,以揭示凋落物多样性、物种丰富度和功能分散(FDis,一种功能丰富度和发散度的度量)两个方面对沿明显气候和植被的凋落物分解的影响梯度范围从阿塔卡马沙漠(26°S)到智利的潮湿温带森林(38°S)。使用不同的功能性状集来计算 FDis,我们研究了与垫料类型之间的资源转移相关的营养相关性状,或与抑制分解相关的次生化合物对非加性垫料混合效应是否重要(图 1)。具体来说,我们假设如下:(1) 积极的非加性凋落物混合效应在水分约束较少的生态系统中更为频繁,随着水分约束的增加而减少,最终在最干旱的生态系统中变为负值。(2) 基于营养性状的凋落物功能多样性(FDis)的增加,正混合效应变得更强,而基于次生化合物的凋落物功能多样性(FDis)增加,负混合效应变得更强(图1)。(3) 在分解的早期阶段,非加性凋落物混合效应更为频繁,此时驱动非加性效应的性状差异仍然最为明显。随着基于次生化合物的垃圾 FDis 增加,负混合效应变得更强(图 1)。(3) 在分解的早期阶段,非加性凋落物混合效应更为频繁,此时驱动非加性效应的性状差异仍然最为明显。随着基于次生化合物的垃圾 FDis 增加,负混合效应变得更强(图 1)。(3) 在分解的早期阶段,非加性凋落物混合效应更为频繁,此时驱动非加性效应的性状差异仍然最为明显。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号