Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2022-05-21 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.13927 Louis A. Mielke 1 , Alf Ekblad 2 , Roger D. Finlay 1 , Petra Fransson 1 , Björn D. Lindahl 3 , Karina E. Clemmensen 1

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Much of the boreal forest is a continuous expanse of ectomycorrhizal trees and ericoid mycorrhizal understorey shrubs (Romell, 1938, Lahti & Väisänen, 1987, Read et al., 2004, Kron & Lutyen, 2005), yet the potentially contrasting and interactive effects of these functional groups on below-ground processes are often overlooked. Multiple, global-scale analyses indicate that higher latitude ecosystems dominated by ectomycorrhizal trees accumulate more soil organic matter than lower latitude arbuscular mycorrhizal ecosystems (Averill et al., 2014; Read, 1991; Soudzilovskaia et al., 2019; Steidinger et al., 2019). However, within high latitude systems, there are multiple studies pointing to an increase in soil organic matter stocks along gradients from ectomycorrhizal to ericoid mycorrhizal dominance (Clemmensen et al., 2013, 2021; Friggens et al., 2020; Hartley et al., 2012; Read, 1991; Ward et al., 2021). In much of the boreal forest, ericaceous dwarf shrubs and trees coexist and have spatially overlapping root systems. Ericaceous roots are located largely in the organic horizon (mor layer; Persson, 1983) and their hair roots are typically colonized by a range of ascomycetous fungi including ericoid mycorrhizal species (Kohout et al., 2011; Lindahl et al., 2007). Tree fine roots are more extensively distributed across soil horizons, but typically with highest density at the interface between mineral and organic layers (Persson, 1983; Rosling et al., 2003). The ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with tree roots are primarily basidiomycetes with prominent mycelia extending into the surrounding soil (Rosling et al., 2003). Trees and ericaceous shrubs with their root-associated fungal communities have contrasting ecological niches, and appear to affect soil C and N dynamics in contrasting ways on both small and large scales (Clemmensen et al., 2015; Sietiö et al., 2018; Ward et al., 2021).

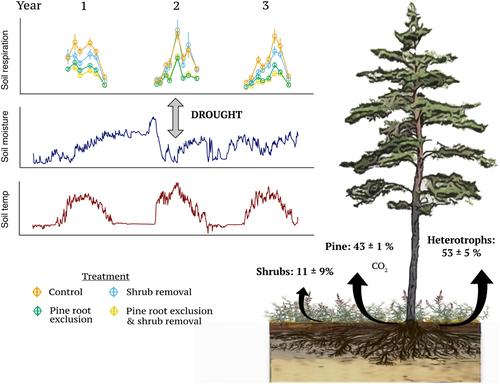

Soil respiration is the most important biological process that leads to losses of soil organic carbon from terrestrial ecosystems, and consequently, knowledge of how soil respiration is partitioned into autotrophic and heterotrophic components is vital to understand soil respiration dynamics and ecosystem carbon budgets (Chapin III et al., 2009; Högberg et al., 2001). An autotrophic component in this case, is defined as the respiration that directly depends on plant carbon allocation to roots, mycorrhizal fungi and other closely associated organisms. Heterotrophic respiration is defined as the respiration that is independent of recent below-ground plant allocation, and instead depends on the decomposition of organic matter by free-living organisms. In forests, plant-driven contributions to soil respiration have been estimated in experiments where the below-ground carbon flow was interrupted by stem girdling or root exclusion (i.e. trenching; Subke et al., 2006). One girdling study in a boreal forest demonstrated a decrease in soil respiration of 54% (within 1–2 months) with a steep decrease just 5 days after below-ground inputs were disrupted (Högberg et al., 2001). A meta-analysis of 25 independent experiments in boreal coniferous forests found, on average, higher heterotrophic (65%) than autotrophic (35%) contributions to soil respiration (Subke et al., 2006). However, in all these studies, understorey shrubs were removed (see Bond-Lamberty et al., 2004; Haynes & Gower, 1995; Vogel et al., 2005), absent or ignored (Lavigne et al., 2003; O'Connell et al., 2003), despite their generally high abundance in boreal forests (Kron & Lutyen, 2005; Nilsson & Wardle, 2005; Romell, 1938).

Only a few studies have estimated contributions of ericaceous dwarf shrubs to soil respiration, and they have provided a wide range of results from almost no effect (Friggens et al., 2020; Kritzler et al., 2016) to contributions between 8% and 55% (Kopittke et al., 2013; Ryhti et al., 2021). Unaccounted respiration by dwarf shrubs could lead to an overestimation of the heterotrophic contribution in tree root exclusion studies, especially in boreal ecosystems where net primary productivity of the understorey may be comparable to trees (Nilsson & Wardle, 2005; Wardle et al., 2012). Furthermore, soil respiration mediated by saprotrophs, pine roots and ericaceous dwarf shrubs may elicit different responses to variation in soil moisture and temperature, since they occupy different parts of the soil profile (Lindahl et al., 2007; Persson, 1983), and harbour fungi with different ecological strategies (Clemmensen et al., 2015; Sietiö et al., 2018).

Nitrogen limitation is the primary constraint on plant growth in boreal forests (Tamm, 1991) and both ecto- and ericoid mycorrhizal symbioses have likely evolved to overcome low nutrient availability caused by retention of nutrients in the organic topsoil (Read & Perez-Moreno, 2003). Ericoid mycorrhizal fungi have been found to mobilize N from organic sources such as 15N-enriched ectomycorrhizal fungal necromass, both in laboratory microcosms (Kerley & Read, 1997) and after canopy girdling, indicating that relaxed competition for N benefitted the shrubs (Bhupinderpal Singh et al., 2003). More recently, it has been recognized that some boreal ectomycorrhizal fungi may be even more efficient in accessing organic N sources than ericoid mycorrhizal fungi, through their production of oxidative enzymes and Fenton reaction mechanisms (Bödeker et al., 2014; Lindahl & Tunlid, 2015; Rineau et al., 2012). Heterotrophic contributions however tend to be over-estimated in root exclusion and girdling experiments, as saprotrophic growth, decomposition and respiration are stimulated by the flush of recently cut mycorrhizal roots and mycelium (Comstedt et al., 2011; Hanson et al., 2000; Lindahl et al., 2010; Savage et al., 2018). A ‘Gadgil effect’ could additionally increase the activity of free-living decomposers because of a competitive release when ectomycorrhizal roots are excluded (Berg & Lindberg, 1980; Fernandez & Kennedy, 2016; Gadgil & Gadgil, 1971; Sterkenburg et al., 2018). Such a competitive release could be linked to increased soil moisture (Comstedt et al., 2011; Koide & Wu, 2003) and/or soil N availability (Fernandez & Kennedy, 2016). Thus, both free-living decomposers and mycorrhizal fungal guilds may experience a competitive release if N availability is increased after pine root exclusion or shrub removal.

Multi-year, in situ estimates of the contribution of understorey ericaceous dwarf shrubs to soil respiration in forested ecosystems, contextualized with soil N availability and microclimate dependencies, are still lacking. We therefore conducted a factorial root exclusion and dwarf shrub removal experiment to assess the contributions and interactions among three respiration sources: pine roots, dwarf shrubs and heterotrophs, to total soil respiration over three growing seasons in an old-growth boreal pine forest. We hypothesized that dwarf shrubs and pine roots contributed to autotrophic respiration in proportion to their relative fine root production at the same site; 30% and 70% for shrubs and trees, respectively (Persson, 1983). Second, we hypothesized that excluding a plant guild would result in increased root-associated respiration and N uptake by the remaining guild, indicating a competitive release. Third, we expected that heterotrophic respiration would contribute, on average, <50% of soil respiration when also accounting for the understorey. Furthermore, we explored how respiration attributed to each of the three sources, that is, heterotrophs, tree and shrub-associated communities, responded to variation in soil moisture and temperature. Disturbed control plots were used to monitor treatment side effects and ectomycorrhizal root and mycelial re-establishment.

中文翻译:

在北方松林中,杜鹃花矮灌木在土壤呼吸中贡献了重要但对干旱敏感的部分

1 简介

大部分北方森林是外生菌根树和石蒜菌根林下灌木的连续广阔区域(Romell, 1938 , Lahti & Väisänen, 1987 , Read et al., 2004 , Kron & Lutyen, 2005)地下过程中的这些功能组经常被忽视。多项全球尺度分析表明,以外生菌根树为主的高纬度生态系统比低纬度丛枝菌根生态系统积累更多的土壤有机质(Averill 等人, 2014 年;Read, 1991 年;Soudzilovskaia 等人, 2019 年;Steidinger 等人, 2019)。然而,在高纬度系统中,有多项研究表明土壤有机质储量随着从外生菌根到橄榄石菌根优势的梯度增加(Clemmensen et al., 2013 , 2021 ; Friggens et al., 2020 ; Hartley et al., 2012 年;阅读, 1991 年;Ward 等人, 2021 年)。在大部分北方森林中,石楠矮灌木和乔木共存,并具有空间重叠的根系。石蜡根主要位于有机层(mor 层;Persson, 1983 年),它们的发根通常被包括石蜡菌根在内的一系列子囊菌定殖(Kohout 等, 2011; Lindahl 等人, 2007 年)。树细根更广泛地分布在土壤层中,但通常在矿物层和有机层之间的界面处密度最高(Persson, 1983;Rosling 等, 2003)。与树根相关的外生菌根真菌主要是担子菌,其突出的菌丝体延伸到周围的土壤中(Rosling 等人, 2003 年)。树木和杜鹃花灌木及其与根相关的真菌群落具有对比鲜明的生态位,并且似乎以不同的方式在小尺度和大尺度上影响土壤 C 和 N 动态(Clemmensen et al., 2015 ; Sietiö et al., 2018 ; Ward等人, 2021 年)。

土壤呼吸是导致陆地生态系统土壤有机碳损失的最重要的生物过程,因此,了解土壤呼吸如何划分为自养和异养成分对于了解土壤呼吸动态和生态系统碳收支至关重要(Chapin III et等人, 2009 年;Högberg 等人, 2001 年)。在这种情况下,自养成分被定义为直接依赖于植物碳分配给根、菌根真菌和其他密切相关的生物的呼吸作用。异养呼吸被定义为独立于最近的地下植物分配的呼吸,而是依赖于自由生物对有机物的分解。在森林中,植物驱动对土壤呼吸的贡献已经在地下碳流被茎环剥或根排除(即挖沟;Subke 等人, 2006 年)中断的实验中进行了估计。在北方森林中进行的一项环带研究表明,土壤呼吸减少了 54%(在 1-2 个月内),在地下输入被破坏后仅 5 天就急剧下降(Högberg 等人, 2001 年)。对北方针叶林 25 项独立实验的荟萃分析发现,平均而言,异养(65%)比自养(35%)对土壤呼吸的贡献更高(Subke 等人, 2006 年)。然而,在所有这些研究中,下层灌木被移除(参见 Bond-Lamberty 等人, 2004 年;Haynes & Gower, 1995 年;Vogel 等人, 2005 年),缺失或被忽略(Lavigne 等人, 2003 年;O'Connell等人, 2003 年),尽管它们在北方森林中的丰度普遍很高(Kron 和 Lutyen, 2005 年;Nilsson 和 Wardle, 2005 年;Romell, 1938 年)。

只有少数研究估计了石楠矮灌木对土壤呼吸的贡献,它们提供了范围广泛的结果,从几乎没有影响(Friggens 等人, 2020 年;Kritzler 等人, 2016 年)到贡献在 8% 到 55 之间%(Kopittke 等人, 2013 年;Ryhti 等人, 2021 年)。矮灌木的不明呼吸可能导致高估树根排斥研究中的异养贡献,特别是在北方生态系统中,下层的净初级生产力可能与树木相当(Nilsson & Wardle, 2005 ; Wardle et al., 2012)。此外,由腐生菌、松树根和杜鹃花矮灌木介导的土壤呼吸可能对土壤水分和温度的变化产生不同的反应,因为它们占据土壤剖面的不同部分(Lindahl 等, 2007;Persson, 1983),并具有具有不同生态策略的真菌(Clemmensen 等人, 2015 年;Sietiö 等人, 2018 年)。

氮限制是北方森林植物生长的主要限制因素(Tamm, 1991 年),外生菌根和橄榄石菌根共生体可能已经进化以克服由于有机表土中养分滞留导致的养分利用率低(Read & Perez-Moreno, 2003 年) )。在实验室微观世界 (Kerley & Read, 1997 ) 和树冠环剥后,已发现石榴石菌根真菌从有机来源(如15富含 N 的外生菌根真菌坏死组织)中动员 N,这表明对 N 的轻松竞争有利于灌木(Bhupinderpal Singh等人, 2003 年)。最近,人们已经认识到,一些北方外生菌根真菌通过产生氧化酶和芬顿反应机制,在获取有机氮源方面可能比石蜡菌根真菌更有效(Bödeker 等人, 2014 年;Lindahl 和 Tunlid, 2015 年) ; 里诺等人, 2012 年)。然而,异养贡献在根排斥和环剥实验中往往被高估,因为腐生生长、分解和呼吸受到最近切割的菌根和菌丝体的刺激(Comstedt 等人, 2011;Hanson 等人, 2000; Lindahl 等人, 2010 年;Savage 等人, 2018 年)。当排除外生菌根时,由于竞争性释放,“Gadgil 效应”可以额外增加自由生活分解者的活动(Berg & Lindberg, 1980 ; Fernandez & Kennedy, 2016 ; Gadgil & Gadgil, 1971 ; Sterkenburg et al., 2018)。这种竞争性释放可能与土壤水分增加(Comstedt 等人, 2011 年;Koide 和 Wu, 2003 年)和/或土壤氮素有效性(Fernandez 和 Kennedy, 2016 年)有关。因此,如果在松根排除或灌木去除后 N 可用性增加,则自由生活的分解者和菌根真菌公会都可能经历竞争释放。

仍然缺乏对林下生态系统土壤呼吸作用的多年原位估计,与土壤氮的可用性和小气候依赖性有关。因此,我们进行了因子根排除和矮灌木去除实验,以评估三种呼吸源之间的贡献和相互作用:松树根、矮灌木和异养生物,在一个古老的北方松林中三个生长季节对土壤总呼吸的贡献和相互作用。我们假设矮灌木和松树根对自养呼吸的贡献与其在同一地点的相对细根产量成正比。灌木和乔木分别为 30% 和 70% (Persson, 1983)。其次,我们假设排除植物公会会导致剩余公会增加根相关呼吸和氮吸收,表明竞争释放。第三,我们预计异养呼吸对土壤呼吸的贡献平均小于 50%,同时也考虑了下层。此外,我们探讨了归因于三种来源的呼吸,即异养生物、树木和灌木相关群落,如何响应土壤湿度和温度的变化。干扰控制图用于监测治疗副作用和外生菌根和菌丝体的重建。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号