Journal of Ecology ( IF 5.3 ) Pub Date : 2022-05-31 , DOI: 10.1111/1365-2745.13936 Dan A. Smale 1 , Harry Teagle 1, 2 , Stephen J. Hawkins 1, 2, 3 , Helen L. Jenkins 1 , Nadia Frontier 4 , Cat Wilding 1 , Nathan King 1 , Mathilde Jackson‐Bué 5 , Pippa J. Moore 6

|

1 INTRODUCTION

Ecological interactions, such as competition, predation and facilitation, play a key role in structuring communities and ecosystems (Kordas et al., 2011; Stachowicz, 2001; Tylianakis et al., 2008). The disproportionate role of foundation species (sensu Dayton, 1972) that alter local environmental conditions and resource availability, often underpinning positive facilitative interactions with other species, has been increasingly appreciated (Bruno & Bertness, 2001; Thomsen et al., 2010). Moreover, such foundation species can also have indirect positive effects on other organisms via cascading interactions (Thomsen et al., 2010). That is, the presence of a secondary habitat-former may elevate biodiversity, but this is itself dependent on the provision or modification of habitat by the primary foundation species (Altieri et al., 2007; Thomsen et al., 2022). These facilitative habitat cascades are prominent across a range of biogeographical contexts, in both terrestrial (Angelini & Silliman, 2014; Cruz-Angón & Greenberg, 2005; Ellwood & Foster, 2004; Stuntz et al., 2002) and marine ecosystems (Bologna & Heck Jr, 1999; Hall & Bell, 1988; Thomsen et al., 2016), but remain poorly described and understood.

Recent rapid anthropogenic warming has led to a global redistribution of ectothermic species as their thermally favourable habitats shift (Poloczanska et al., 2013; Sunday et al., 2012; Thomas, 2010). Range shifts of foundation species can have disproportionate impacts on communities and ecosystems, given that many associated species are reliant on them directly for habitat and/or food, or indirectly via modification of the local environment (Ellison et al., 2005; Smale & Wernberg, 2013; Thomson et al., 2015). In some cases, however, vacating foundation species may be replaced by functionally similar species that provide comparable primary habitat to support secondary habitat-formers and, as such, wider ecosystem functioning and biodiversity may be maintained (Bulleri et al., 2018). Conversely, where shifting foundation species are not replaced or replaced by dissimilar species that do not facilitate secondary habitat-formers, habitat cascades may be disrupted with consequences for associated communities and local biodiversity. Evidence of climate-driven disruption to habitat cascades is lacking, despite the recognised importance of facilitative interactions in a warming world (Stachowicz, 2001).

Kelps are foundation species that dominate shallow rocky reefs along temperate and polar coastlines (Steneck et al., 2002; Wernberg et al., 2019) and the forests they form represent highly diverse and productive ecosystems (Reed et al., 2008; Smale et al., 2013; Teagle et al., 2017). As kelp species distributions are strongly constrained by temperature (Eggert, 2012), they are sensitive to warming trends and range shifts have been observed all over the world (Fernandez, 2011; Filbee-Dexter et al., 2016; Verges et al., 2014), with wide-ranging implications for associated biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (Tuya et al., 2012; Voerman et al., 2013; Wernberg et al., 2013).

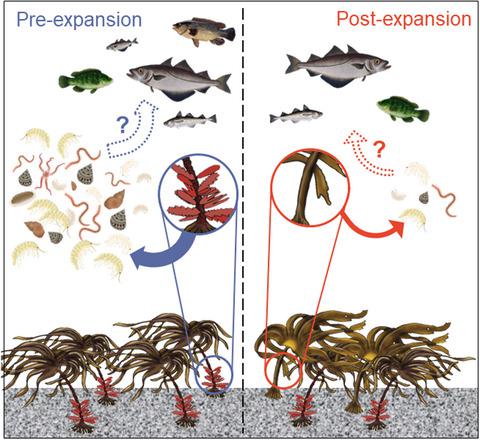

In the North East Atlantic, the cold-adapted boreal species, Laminaria hyperborea, is a dominant habitat-former throughout its distribution from northern Norway to northern Portugal (Figure 1a), particularly on wave-exposed shallow subtidal reefs (Kain, 1979; Smale & Moore, 2017). Atypically among kelp species, L. hyperborea supports abundant epiphytic algal assemblages on its stipe, which serve as secondary habitat-formers (King et al., 2021; Whittick, 1983). This habitat cascade increases living space and complexity for abundant and diverse assemblages of mobile invertebrate fauna, which represent an important food resource for higher trophic levels (King et al., 2021; Norderhaug et al., 2005).

In the United Kingdom (UK), the morphologically similar warm-adapted species, Laminaria ochroleuca, is found towards its leading range edge where it competes with L. hyperborea for space and resources. L. ochroleuca, which is distributed from Morocco and the Mediterranean northwards to the UK and Ireland, has proliferated in southwest UK in recent decades (Teagle & Smale, 2018), and is predicted to expand polewards with continued warming (Assis et al., 2017). Unlike L. hyperborea, however, L. ochroleuca lacks the characteristic secondary habitat provided by stipe-associated epiphytic algae (Smale et al., 2015). Intuitively, a climate-driven substitution of the cold-adapted L. hyperborea with the warm-adapted L. ochroleuca at some locations could disrupt an important habitat cascade, with implications for local biodiversity and higher trophic levels, but evidence is currently lacking. Crucially, relative to facilitation cascades underpinned by other primary foundation species (i.e. seagrass, mangroves, bivalves), little is known about facilitation cascades in kelp forest ecosystems (Gribben et al., 2019).

Here, we adopted mixed kelp forests in the UK as a model system to test the following hypotheses: (1) climate-driven substitution of foundation species leads to a weakening of a facilitative interaction; (2) disruption to an important habitat cascade results in impoverished, distinct mobile invertebrate assemblages; and (3) lower abundances of mobile invertebrates potentially reduce prey availability for higher trophic levels (e.g. predatory fish). We thereby explored the consequences of intra-generic replacements of morphologically similar species, differing only in some superficially small traits, but with likely major consequences for community structure and ecosystem functioning.

中文翻译:

气候驱动的基础物种替代导致促进级联的崩溃,可能对更高的营养水平产生影响

1 简介

竞争、捕食和促进等生态相互作用在构建群落和生态系统中发挥着关键作用(Kordas 等人, 2011 年;Stachowicz, 2001 年;Tylianakis 等人, 2008 年)。基础物种(sensu Dayton, 1972 年)改变当地环境条件和资源可用性的不成比例的作用,通常支持与其他物种的积极促进相互作用,越来越受到重视(Bruno 和 Bertness, 2001 年;Thomsen 等人, 2010 年)。此外,这些基础物种还可以通过级联相互作用对其他生物产生间接的积极影响(Thomsen et al., 2010)。也就是说,次生栖息地形成者的存在可能会提升生物多样性,但这本身取决于主要基础物种对栖息地的提供或改变(Altieri et al., 2007 ; Thomsen et al., 2022)。在陆地(Angelini 和 Silliman, 2014 年;Cruz-Angón 和 Greenberg, 2005 年;Ellwood 和 Foster, 2004 年;Stuntz 等人, 2002 年)和海洋生态系统(Bologna 和Heck Jr, 1999 ; Hall & Bell, 1988 ; Thomsen et al., 2016),但仍然缺乏描述和理解。

最近的快速人为变暖导致了全球变温物种的重新分布,因为它们对热有利的栖息地发生了变化(Poloczanska 等人, 2013 年;Sunday 等人, 2012 年;Thomas, 2010 年)。基础物种的范围变化可能对群落和生态系统产生不成比例的影响,因为许多相关物种直接依赖它们作为栖息地和/或食物,或者通过改变当地环境间接依赖它们(Ellison et al., 2005 ; Smale & Wernberg , 2013 年;汤姆森等人, 2015 年)。然而,在某些情况下,腾出的基础物种可能会被功能相似的物种所取代,这些物种提供可比的主要栖息地以支持次生栖息地形成者,因此可以维持更广泛的生态系统功能和生物多样性(Bulleri 等人, 2018 年)。相反,如果移动的基础物种没有被不利于次生栖息地形成的不同物种取代或取代,栖息地级联可能会被破坏,从而对相关社区和当地生物多样性产生影响。尽管气候变暖的世界中促进相互作用的重要性得到公认,但缺乏气候驱动的对栖息地级联破坏的证据(Stachowicz, 2001)。

海带是温带和极地海岸线浅层岩礁的基础物种(Steneck 等人, 2002 年;Wernberg 等人, 2019 年),它们形成的森林代表了高度多样化和多产的生态系统(Reed 等人, 2008 年;Smale 等人)等人, 2013 年;Teagle 等人, 2017 年)。由于海带物种分布受到温度的强烈限制(Eggert,2012 年),它们对变暖趋势很敏感,并且在世界各地都观察到范围变化(Fernandez, 2011 年;Filbee-Dexter 等人, 2016 年;Verges 等人, 2014),对相关的生物多样性和生态系统功能具有广泛的影响(Tuya 等人, 2012 年;Voerman 等人, 2013 年;Wernberg 等人, 2013 年)。

在大西洋东北部,适应寒冷的北方物种,海带,是从挪威北部到葡萄牙北部的主要栖息地形成者(图 1a),特别是在波浪暴露的浅潮下带珊瑚礁上(Kain, 1979 年;Smale和摩尔, 2017 年)。在海带物种中非典型的是,L. hyperborea在其菌柄上支持丰富的附生藻类组合,作为次生栖息地形成者(King 等人, 2021 年;Whittick, 1983 年)。这种栖息地级联增加了丰富多样的移动无脊椎动物群的生存空间和复杂性,它们代表了更高营养水平的重要食物资源(King 等, 2021; Norderhaug 等人, 2005 年)。

在英国 (UK),在其主要分布范围边缘发现了形态相似的暖适应物种海带,它与L. hyperborea竞争空间和资源。L. ochroleuca分布于摩洛哥和地中海向北到英国和爱尔兰,近几十年来在英国西南部大量繁殖(Teagle & Smale, 2018),预计随着持续变暖将向极地扩张(Assis et al., 2017 年)。然而,与L. hyperborea不同的是, L. ochroleuca缺乏由菌柄相关的附生藻类提供的特征性次生栖息地(Smale et al., 2015)。直观地说,在某些地方用温适应的L. ochroleuca替代冷适应的L. hyperborea可能会破坏重要的栖息地级联,对当地的生物多样性和更高的营养水平产生影响,但目前缺乏证据。至关重要的是,相对于以其他主要基础物种(即海草、红树林、双壳类)为基础的促进级联,人们对海带森林生态系统中的促进级联知之甚少(Gribben 等人, 2019 年)。

在这里,我们采用英国混合海带林作为模型系统来检验以下假设:(1)气候驱动的基础物种替代导致促进相互作用减弱;(2) 对重要栖息地级联的破坏导致贫瘠的、独特的移动无脊椎动物群落;(3) 移动无脊椎动物的丰度较低可能会降低较高营养水平的猎物可用性(例如捕食性鱼类)。因此,我们探索了形态相似物种的属内替代的后果,仅在一些表面上的小特征上有所不同,但可能对群落结构和生态系统功能产生重大影响。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号