PLOS Medicine ( IF 15.8 ) Pub Date : 2017-12-27 , DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002479 Emma Wilson 1 , Caroline Free 1 , Tim P Morris 2 , Jonathan Syred 3 , Irrfan Ahamed 1 , Anatole S Menon-Johansson 4 , Melissa J Palmer 1 , Sharmani Barnard 3 , Emma Rezel 3 , Paula Baraitser 3, 5

|

Background

Internet-accessed sexually transmitted infection testing (e-STI testing) is increasingly available as an alternative to testing in clinics. Typically this testing modality enables users to order a test kit from a virtual service (via a website or app), collect their own samples, return test samples to a laboratory, and be notified of their results by short message service (SMS) or telephone. e-STI testing is assumed to increase access to testing in comparison with face-to-face services, but the evidence is unclear. We conducted a randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of an e-STI testing and results service (chlamydia, gonorrhoea, HIV, and syphilis) on STI testing uptake and STI cases diagnosed.

Methods and findings

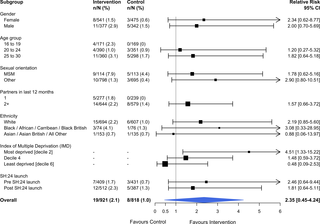

The study took place in the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark. Between 24 November 2014 and 31 August 2015, we recruited 2,072 participants, aged 16–30 years, who were resident in these boroughs, had at least 1 sexual partner in the last 12 months, stated willingness to take an STI test, and had access to the internet. Those unable to provide consent and unable to read English were excluded. Participants were randomly allocated to receive 1 text message with the web link of an e-STI testing and results service (intervention group) or to receive 1 text message with the web link of a bespoke website listing the locations, contact details, and websites of 7 local sexual health clinics (control group). Participants were free to use any other services or interventions during the study period. The primary outcomes were self-reported STI testing at 6 weeks, verified by patient record checks, and self-reported STI diagnosis at 6 weeks, verified by patient record checks. Secondary outcomes were the proportion of participants prescribed treatment for an STI, time from randomisation to completion of an STI test, and time from randomisation to treatment of an STI. Participants were sent a £10 cash incentive on submission of self-reported data. We completed all follow-up, including patient record checks, by 17 June 2016. Uptake of STI testing was increased in the intervention group at 6 weeks (50.0% versus 26.6%, relative risk [RR] 1.87, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.15, P < 0.001). The proportion of participants diagnosed was 2.8% in the intervention group versus 1.4% in the control group (RR 2.10, 95% CI 0.94 to 4.70, P = 0.079). No evidence of heterogeneity was observed for any of the pre-specified subgroup analyses. The proportion of participants treated was 1.1% in the intervention group versus 0.7% in the control group (RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.71 to 4.16, P = 0.231). Time to test, was shorter in the intervention group compared to the control group (28.8 days versus 36.5 days, P < 0.001, test for difference in restricted mean survival time [RMST]), but no differences were observed for time to treatment (83.2 days versus 83.5 days, P = 0.51, test for difference in RMST). We were unable to recruit the planned 3,000 participants and therefore lacked power for the analyses of STI diagnoses and STI cases treated.

Conclusions

The e-STI testing service increased uptake of STI testing for all groups including high-risk groups. The intervention required people to attend clinic for treatment and did not reduce time to treatment. Service innovations to improve treatment rates for those diagnosed online are required and could include e-treatment and postal treatment services. e-STI testing services require long-term monitoring and evaluation.

Trial registration

ISRCTN Registry ISRCTN13354298.

中文翻译:

互联网访问性传播感染 (e-STI) 检测和结果服务:一项随机、单盲、对照试验

背景

互联网上的性传播感染检测(e-STI 检测)越来越多地用作诊所检测的替代方法。通常,这种测试方式使用户能够从虚拟服务(通过网站或应用程序)订购测试套件,收集自己的样本,将测试样本返回实验室,并通过短信服务 (SMS) 或电话通知他们的结果. 与面对面服务相比,e-STI 测试被认为可以增加获得测试的机会,但证据尚不清楚。我们进行了一项随机对照试验,以评估 e-STI 检测和结果服务(衣原体、淋病、HIV 和梅毒)对 STI 检测和诊断的 STI 病例的有效性。

方法和发现

该研究在伦敦的兰贝斯和南华克区进行。2014 年 11 月 24 日至 2015 年 8 月 31 日期间,我们招募了 2,072 名年龄在 16-30 岁之间的参与者,他们居住在这些行政区,在过去 12 个月内至少有 1 个性伴侣,表示愿意接受 STI 测试,并且可以访问到互联网。那些无法提供同意和无法阅读英语的人被排除在外。参与者被随机分配接收 1 条带有 e-STI 测试和结果服务(干预组)的网络链接的短信,或接收 1 条带有列出位置、联系方式和网站的定制网站的网络链接的短信。 7 家当地性健康诊所(对照组)。在研究期间,参与者可以自由使用任何其他服务或干预措施。主要结果是 6 周时自我报告的 STI 检测,通过患者记录检查进行验证,以及在 6 周时自我报告的 STI 诊断,通过患者记录检查进行验证。次要结果是接受 STI 治疗的参与者比例、从随机化到完成 STI 测试的时间以及从随机化到 STI 治疗的时间。参与者在提交自我报告的数据时获得了 10 英镑的现金奖励。截至 2016 年 6 月 17 日,我们完成了所有随访,包括患者记录检查。干预组在第 6 周时增加了 STI 检测的使用率(50.0% 对 26.6%,相对风险 [RR] 1.87,95% CI 1.63 至 2.15 , 次要结果是接受 STI 治疗的参与者比例、从随机化到完成 STI 测试的时间以及从随机化到 STI 治疗的时间。参与者在提交自我报告的数据时获得了 10 英镑的现金奖励。我们在 2016 年 6 月 17 日之前完成了所有随访,包括患者记录检查。干预组在第 6 周时增加了 STI 检测的使用率(50.0% 对 26.6%,相对风险 [RR] 1.87,95% CI 1.63 到 2.15 , 次要结果是接受 STI 治疗的参与者比例、从随机化到完成 STI 测试的时间以及从随机化到 STI 治疗的时间。参与者在提交自我报告的数据时获得了 10 英镑的现金奖励。我们在 2016 年 6 月 17 日之前完成了所有随访,包括患者记录检查。干预组在第 6 周时增加了 STI 检测的使用率(50.0% 对 26.6%,相对风险 [RR] 1.87,95% CI 1.63 到 2.15 ,P < 0.001)。干预组确诊的参与者比例为 2.8%,对照组为 1.4%(RR 2.10,95% CI 0.94 至 4.70,P = 0.079)。对于任何预先指定的亚组分析,均未观察到异质性证据。干预组接受治疗的参与者比例为 1.1%,而对照组为 0.7%(RR 1.72,95% CI 0.71 至 4.16,P = 0.231)。与对照组相比,干预组的测试时间较短(28.8 天对 36.5 天,P < 0.001,检验限制平均生存时间 [RMST] 的差异),但未观察到治疗时间的差异(83.2天与 83.5 天,P =0.51,检验 RMST 的差异)。我们无法招募计划的 3,000 名参与者,因此缺乏对 STI 诊断和治疗的 STI 病例进行分析的能力。

结论

e-STI 检测服务增加了包括高危人群在内的所有群体的 STI 检测。干预要求人们到诊所接受治疗,并没有减少治疗时间。需要进行服务创新以提高在线诊断患者的治疗率,其中可能包括电子治疗和邮政治疗服务。e-STI 测试服务需要长期监控和评估。

京公网安备 11010802027423号

京公网安备 11010802027423号