Abstract

Background

In ICU patients, digestive tract colonization by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative (G−) bacteria is a significant risk factor for the development of infections. In patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), colonization by MDR bacteria and risk of subsequent nosocomial infections (NIs) have not been studied yet. The aim of this study is to evaluate the incidence, etiology, risk factors, impact on outcome of gastrointestinal colonization by MDR G− bacteria, and risk of subsequent infections in patients undergoing ECMO.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data: 105 consecutive patients, treated with ECMO, were admitted to the ICU of an Italian tertiary referral center (San Gerardo Hospital, Monza, Italy) from January 2010 to November 2015. Rectal swabs for MDR G− bacteria were cultured at admission and twice a week. Only colonization and NIs by MDR G− bacteria were analyzed.

Results

Ninety-one included patients [48.5 (37–56) years old, 63% male, simplified acute physiology score II 37 (32–47)] underwent peripheral ECMO (87% veno-venous) for medical indications (79% ARDS). Nineteen (21%) patients were colonized by MDR G− bacteria. Male gender (OR 4.03, p = 0.029) and duration of mechanical ventilation (MV) before ECMO > 3 days (OR 3.57, p = 0.014) were associated with increased risk of colonization. Colonized patients had increased odds of infections by the colonizing germs (84% vs. 29%, p < 0.001, OR 12.9), longer ICU length of stay (LOS) (43 vs. 24 days, p = 0.002), MV (50 vs. 22 days, p < 0.001) and ECMO (28 vs. 12 days, p < 0.001), but did not have higher risk of death (survival rate 58% vs. 67%, p = 0.480, OR 0.68). Infected patients had almost halved ICU survival (46% vs. 78%, p < 0.001, OR 4.11).

Conclusions

In patients undergoing ECMO for respiratory and/or circulatory failure, colonization by MDR G− bacteria is frequent and associated with more the tenfold odds for subsequent infection. Those infections are associated with an increased risk of death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is a life-support technique used in patients with potentially reversible refractory respiratory or circulatory failure [1]. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are common in ECMO patients [2,3,4] due to several predisposing factors: intensive care unit (ICU) hospitalization, patients’ comorbidities, immunodeficiency induced by the critical illness and invasiveness of ECMO and other life-support procedures (e.g., invasive mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapies). ECMO patients suffering from HAIs have longer ECMO runs, ICU length of stay (LOS), and higher mortality rate [3]. Recently, we reported that HAIs during ECMO are frequently caused by multidrug-resistant (MDR) Gram-negative (G−) bacteria [2], and we observed that patients infected by MDR bacteria had higher odds for death.

ICU patients have higher rates of digestive tract colonization by MDR G− bacteria (i.e., producing extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL+) and carbapenem-resistant bacteria) compared to patients admitted to general wards [5, 6]. Such colonizations could represent a significant risk factor for the development of subsequent infections [7,8,9]. A growing body of evidence indicates that dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is common in critically ill patients and may play a crucial role in increasing the risk of gastrointestinal colonization. To our knowledge, the rate of colonization by MRD bacteria and the risk of subsequent infections have not been studied in ECMO patients. In such a fragile population, prevention, early diagnosis and prompt treatment of MDR HAIs may significantly affect morbidity and mortality.

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the incidence, risk factors, and impact on subsequent HAIs as well as clinical outcomes of digestive tract colonization by MDR G− bacteria in a large cohort of non-surgical patients undergoing ECMO for respiratory or circulatory failure.

Methods

We present a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data of all consecutive ECMO patients admitted to the General Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of San Gerardo Hospital (Monza, Italy) from January 2010 to November 2015. For further details on ECMO setting and patient care see Setting and Standard of Care, Additional file 1: Methods S1. Notably, at San Gerardo Hospital ICU, rectal swabs are collected and cultured for ESBL+ (i.e., E. coli, Enterobacter spp.) and carbapenem-resistant (i.e., Acinetobacter spp., P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae carbapenemase producing and other Enterobacteriaceae) G− bacteria at ICU admission and twice a week. We will refer to ESBL+ and carbapenem-resistant G− bacteria as “MDR G− bacteria”.

The Institutional Ethical Committee, and written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective observational design of the study. All patients receiving ECMO support were considered for inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: (1) ICU length of stay (LOS) < 24 h; (2) ECMO use < 24 h; (3) occurrence of a NI prior to ECMO connection; (4) missing medical records. At baseline, the following patients data and ECMO parameters were collected: demographics (i.e., gender, age); comorbidities [10]; immunocompromised status (i.e., chronic immunosuppressive therapies, active hematological malignancies, autoimmune diseases); diagnosis at admission; infections at admission; renal replacement therapy before ECMO cannulation; severity scores (i.e., Sequential Organ Failure Assessment—SOFA—score and Simplified Acute Physiology Score II—SAPS II of the first 24 h of ICU stay); PaO2/FiO2 at ECMO connection; ECMO configuration (i.e., veno-venous, veno-arterial, other); transfer from peripheral hospital; length of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) before ECMO connection; antimicrobial therapy (i.e., exposure to extended-spectrum penicillins with β-lactamase inhibitor or carbapenems).

The following outcomes were recorded: survival at ICU discharge, ICU LOS, duration of IMV, and duration of ECMO.

All the positive microbial cultures obtained from ICU admission until ICU dismissal have been independently evaluated in light of the available clinical, laboratory, and radiographic data by two specialized intensivists (VS and GG) and two infectious diseases specialists (AB and LA) following international guidelines [11,12,13]. The patients with rectal or perineal swabs positive for MDR G− bacteria were considered “colonized”. Similarly, patients with diagnostic criteria for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), catheter-associated urinary tract infection (UTI), bloodstream infection (BSI), catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) (see Additional file 1: Table S1, Methods S1) [9] due to MDR G− bacteria were considered “infected”. Infections due to pathogens different from MDR G− bacteria were not considered in this analysis and have been described elsewhere [2].

Statistical analysis

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no statistical power calculation was performed a priori, and the sample size was equal to the number of patients treated during the recruitment period. Data are presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. Categorical variables are expressed as number of patients (percentage of the subgroups). For binary outcome measures, odds ratios (OR) and associated 95% likelihood ratio-based confidence intervals were calculated, and the comparison between patients’ populations (i.e., colonized vs. non-colonized, infected vs. non-infected) were performed with Chi-square test or Fisher’s test, as appropriate. The Kruskal–Wallis test was utilized to compare non-parametric continuous variables between patients’ populations. Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis was used with log-rank test for comparison of colonization-free and infection-free rates. Observations were right-censored.

Univariate regression models were applied to identify risk factors associated with colonization and infection. All subjects were included in the models, and follow-up began at the time of ECMO initiation. All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using JMP 12.1 Pro (SAS, Cary, NC, USA) statistical program.

Results

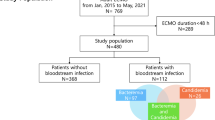

From January 2010 to November 2015, 105 patients were treated with ECMO at the General Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of San Gerardo Hospital (Monza, Italy). Ninety-one subjects (median age 49 years; 63% male) were included in the analysis. Reasons for exclusion of the remaining patients were: diagnosis of HAI prior to ECMO connection (10 patients), age < 18 years (2 subjects), ICU LOS and ECMO shorter than 24 h (2 patients) (see Additional file 1: Figure S1, Results).

Patients’ characteristics, comorbidities, and indications for ECMO support are summarized in Table 1, and Additional file 1: Table S2.

We analyzed a total of 1213 positive cultures. Nineteen (21%) patients were colonized by MDR G− bacteria. Of them, 11 (58%) were colonized by A. baumannii, 4 (21%) by K. pneumoniae, 2 (11%) by P. aeruginosa, and 2 (10%) by other Enterobacteriaceae. The clinical characteristics of colonized and non-colonized patients are depicted in Table 2. Factors associated with increased risk for colonization were male gender [OR 4.03 (1.08–15.0), p = 0.029] and duration of IMV before ECMO connection > 3 days [OR 3.57 (1.25–10.2), p = 0.014]. Among the other variables, ARDS and use of RRT prior to ECMO connection were associated with high, but not significant, OR estimates [i.e., 6.00 (0.74–48.2) and 1.48 (0.41–5.29), respectively]. Multivariable logistic regression was not deemed appropriate due to the small number of events (i.e., n = 19).

Colonization was diagnosed after a median interval of 13 (1–22), 16 (8–32) and 17 (10–34) days from ECMO connection, institution of IMV, and hospital admission, respectively. Of note, 5 (26%) of the colonization were diagnosed in the first three days after ICU admission. The time course of colonization is depicted in Fig. 1.

Colonized patients had significantly longer ICU LOS [i.e., 43 (23–84) vs. 24 (12–37), p = 0.002], longer IMV [i.e., 50 (23–89) vs. 22 (10–37) days, p < 0.001] and longer ECMO support [i.e., 28 (16–60) vs. 12 (6–24), p < 0.001]. Colonization also increased the risk of need for tracheostomy [i.e., 68% vs. 28%, p < 0.001, OR 5.63 (1.88–16.8)]. In our cohort colonized patients did not have a higher risk of death than not colonized patients [survival rate 58% vs. 67%, p = 0.480, OR 0.68 (0.24–1.93)], but they had more than tenfold odds of developing an infection caused by the colonizing germs [84% vs. 29%, p < 0.001, OR 12.9 (3.41–49.1)] with high sensitivity [0.432 (95% CI 0.287–0.591)] and specificity [0.944 (95% CI 0.849–0.981)] of prior colonization to predict subsequent MDR G− bacterial infection.

In colonized patients, we observed 13 VAP, 2 UTI, and 1 CRBSI at a median of 11 (4–22) days from the day of diagnosis of colonization and 24 (13–60), 33 (19–47) and 34 (20–64) days from ECMO connection, intubation and hospital admission, respectively.

Overall, 37/91 patients (41%) developed an infection due to MDR G− bacteria (see Additional file 1: Figure S2, Tables S3, S4), which occurred at a median of 16 (7–31), 22 (12–45) and 25 (15–40) days from ECMO connection, intubation and hospital admission. The most common infection was VAP due to A. baumannii, both in the colonized (n = 7/16 infected patients, 44%) and non-colonized (n = 5/21 infected patients, 25%).

The clinical characteristics of infected and non-infected patients are depicted in Table 3. Factors associated with increased risk for infection were male gender [OR 2.68 (1.09–7.00), p = 0.030], duration of IMV before ECMO connection > 3 days [OR 7.33 (2.86–20.3), p = 0.001], use of RRT prior to ECMO connection [OR 5.29 (1.63–20.6), p = 0.001], diagnosis of ARDS [OR 8.04 (2.09–53.0), p = 0.001], infection at admission [OR 3.28 (1.22–9.93), p = 0.017] and colonization [OR 12.9 (3.83–59.9, p = 0.001]. Kaplan–Meier survival curve analysis with log-rank test showed a significant difference in the time course of infection between colonized and non-colonized patients (p = 0.025), indicating that infections developed earlier in colonized patients (Fig. 2).

Infected patients had longer ECMO support [i.e., 27 (14–61) vs. 10 (5–16), p < 0.001], longer IMV [i.e., 44 (25–87) vs. 18 (9–31), p < 0.001] and longer ICU LOS [i.e., 43 (25–83) vs. 19 (10–29), p < 0.001]. Moreover, infected patients had increased needs for RRT [i.e., 22 (59%) vs. 11 (20%), p < 0.001, OR 5.73 (2.31–15.6)] and tracheostomy [i.e., 18 (49%) vs. 15 (28%), p = 0.042, OR 2.46 (1.03–6.01)]. Finally, infected patients had almost halved ICU survival [i.e., 17 (46%) vs. 42 (78%), p < 0.001, OR 4.11 (1.68–10.5)].

The time course of antibiotic use is shown in Additional file 1: Table S5. β-Lactam/β-lactamase inhibitors and antipseudomonal carbapenems were the most commonly employed antibiotic classes at time of perineal and rectal swab collection, while antipseudomonal carbapenems and colistin were the most common classes of antibiotics introduced as empiric and cultured-targeted therapy.

Discussion

In the present study, we analyzed the epidemiology of digestive tract colonization by MDR G− bacteria in a large cohort of non-surgical patients undergoing ECMO for respiratory or circulatory failure. MDR G− bacteria colonization was highly frequent (21% of the patients), and risk factors associated with colonization were male sex and the need for prolonged (i.e., > 3 days) IMV prior to ECMO connection. Colonized patients had more than tenfold odds for subsequent infection by MDR G− bacteria, and those infections (mainly VAP due to A. baumannii) were associated with an increased risk of death [14].

In a previous analysis [2], we observed that up to 55% of ECMO patients develop at least an infectious complication, which is associated with worse clinical outcomes. Of those infections, 56% were caused by MDR bacteria, particularly non-fermenting G− bacteria. At San Gerardo Hospital general ICU, rectal swabs are routinely collected and cultured for MDR G− bacteria at ICU admission and twice a week. We hypothesized that, in patients undergoing ECMO, digestive tract colonization might precede infection and thus we retrospectively evaluated such cultures and their relationship with subsequent infections. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the relationship between multidrug resistant bacteria gut colonization and infections in a relatively large cohort of ECMO patients.

Recent studies performed in European ICUs [15, 16], described colonization by MDR G− pathogens to occur in 2–10% of the patients. The higher rate of colonization documented in our patient population may be explained by several factors. First, in the last decade, Mediterranean countries and Italy, in particular, have been plagued by an epidemic of MDR bacteria in hospitalized patients and even in the general population [17, 18], with ESBL+ colonization reaching up to 50% of the patients [19]. Second, the high rate of colonization may reflect the invasiveness of treatment [20, 21] of our patients. Indeed, all our patients were invasively ventilated, and up to 50% underwent CRRT. We observed that longer duration of IMV prior to ECMO and male gender were associated with increased risk of colonization, while the use of RRT before ECMO cannulation had elevated though non-significant odds ratios for colonization. Third, ECMO patients usually receive broad-spectrum antimicrobials, which increase the risk of selection of MDR germs [9, 22]. Contrary to previous literature [23, 24], in our patients’ cohort exposure to carbapenems and extended-spectrum β-lactams/β-lactamase inhibitors and severity of illness (SOFA, SAPS II and PaO2/FiO2 ratio) were not associated with an increased risk of colonization by G− MDR bacteria. Finally, both invasiveness of care [21] and critical illness itself [25] alter the patients’ microbiota (i.e., lower diversity, lower abundance of commensals genera, overgrowth by single genera), limiting the protective role of microbiome thus increasing susceptibility to infection [26].

As previously documented [8, 9, 27], colonization by MDR G− bacteria was independently associated with increased odds for subsequent infection from the colonizing bacteria. While colonization per se was not associated with an increased risk of death, colonized patients had increased length of mechanical ventilation and ICU stay. In addition, infected patients had more than fourfold odds of death as compared to non-infected patients. In our opinion, the finding that infection but not colonization is associated with an increased risk of death is of utmost clinical interest. Treatment of bacterial colonization with broad-spectrum antibiotics is not recommended in patients with critical illness-associated immune dysfunction since it usually does not achieve the eradication of colonizing germs, while it instead increases evolutionary pressure towards the selection of multidrug resistant bacteria [28, 29]. Contrarily, management of colonization should aim at (1) early recognizing colonization through active screening protocols and molecular biology techniques [30]; (2) limiting the spread of MDR bacteria (by enforcing hand hygiene, contact precautions and cohort isolation [31]), and ideally, (3) avoiding development of infection in colonized patients; (4) institute patient-specific antibiotic therapy when a new infection would develop [28]. To reach the latest goal, immunologic profiling [32] of patients at highest risk for progression from colonization to infection would be crucial, also to guide the eventual institution of immunomodulating treatments. Also, we believe that gut microbiota may be a relevant therapeutic target for specific interventions (such as probiotics administration, decolonization strategies, etc.) that might contribute to reducing the risk of digestive tract colonization by MDR bacteria. Further prospective observational studies are needed to evaluate such aspects.

In our patient cohort, colonization by MDR G− bacteria occurred in patients with longer ICU stay, longer IMV and higher invasiveness of care, but was not associated with an increased risk of death. As such, colonization may be considered as a proxy for a more complicated clinical course, rather than a causative determinant of the unfavorable clinical course.

The main limitation of our study is its retrospective and single-center nature, which precludes the generalization of the results to the overall population of medical ECMO patients. Moreover, colonization due to MDR G+ bacteria (namely methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) was not evaluated since routine surveillance for MRSA colonization is not performed at San Gerardo Hospital General ICU due to the limited incidence of such infection. Finally, since around 25% of the colonizations occurred in the first 3 days from ICU admission, in this specific subgroup, we cannot clearly distinguish between community-acquired and hospital-acquired colonization, as most of our patients were admitted from peripheral hospitals, where surveillance was rarely performed.

Conclusions

In a large cohort of non-surgical patients undergoing ECMO for respiratory and/or circulatory failure, colonization by MDR G− bacteria was frequent, associated with male sex and with prolonged duration (i.e., > 3 days) of IMV prior to ECMO connection. Colonized patients had more than tenfold odds for subsequent infection by MDR G− bacteria, and those infections were associated with an increased risk of death.

Availability of data and materials

All the anonymized raw database is available after request to the corresponding author.

References

Raman L, Dalton HJ. Year in review 2015: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Respir Care. 2016;61(7):986–91.

Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Di Bella S, et al. Nosocomial infections during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: incidence, etiology, and impact on patients’ outcome. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(10):1726–33.

Biffi S, Di Bella S, Scaravilli V, et al. Infections during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis and prevention. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;50(1):9–16.

Hsu MS, Chiu KM, Huang YT, et al. Risk factors for nosocomial infection during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(3):210–6.

Ma X, Wu Y, Li L, et al. First multicenter study on multidrug resistant bacteria carriage in Chinese ICUs. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1–10.

Azim A, Dwivedi M, Rao PB, et al. Epidemiology of bacterial colonization at intensive care unit admission with emphasis on extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and metallo-β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria—an Indian experience. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:955–60.

Barbier F, Bailly S, Schwebel C, et al. Infection-related ventilator-associated complications in ICU patients colonised with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(5):616–26.

Dautzenberg MJD, Wekesa AN, Gniadkowski M, et al. The association between colonization with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and overall ICU mortality: an observational cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(6):1170–7.

Razazi K, Derde LPG, Verachten M, et al. Clinical impact and risk factors for colonization with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing bacteria in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1769–78.

Ladha KS, Zhao K, Quraishi SA, et al. The Deyo-Charlson and Elixhauser-van Walraven comorbidity indices as predictors of mortality in critically ill patients. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008990.

American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America: guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(4):388–416.

Hooton TM, Bradley SF, Cardenas DD, et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(5):625–63.

Mermel LA, Allon M, Bouza E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the infectious diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(1):1–45.

Du B, Long Y, Liu H, et al. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection: risk factors and clinical outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(12):1718–23.

Detsis M, Karanika S, Mylonakis E. ICU acquisition rate, risk factors, and clinical significance of digestive tract colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):705–14.

Cantón R, Akóva M, Carmeli Y, et al. Rapid evolution and spread of carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(5):413–31.

Giani T, Antonelli A, Caltagirone M, et al. Evolving beta-lactamase epidemiology in Enterobacteriaceae from Italian nationwide surveillance, October 2013: KPC-carbapenemase spreading among outpatients. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22(31):1–11.

Principe L, Piazza A, Mauri C, et al. Multicenter prospective study on the prevalence of colistin resistance in Escherichia coli: relevance of mcr-1-positive clinical isolates in Lombardy, Northern Italy. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:377–85.

Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, et al. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(3):310–8.

Jung JY, Park MS, Kim SE, et al. Risk factors for multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia in patients with colonization in the intensive care unit. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:228.

Zhou HY, Yuan Z, Du YP. Prior use of four invasive procedures increases the risk of Acinetobacter baumannii nosocomial bacteremia among patients in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2014;22:25–30.

Ben-Ami R, Rodríguez-Baño J, Arslan H, et al. A multinational survey of risk factors for infection with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in nonhospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):682–90.

Papadimitriou-Olivgeris M, Marangos M, Fligou F, et al. Risk factors for KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae enteric colonization upon ICU admission. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(12):2976–81.

Gasink LB, Edelstein PH, Lautenbach E, et al. Risk factors and clinical impact of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(12):1180–5.

Lankelma JM, van Vught LA, Belzer C, et al. Critically ill patients demonstrate large interpersonal variation in intestinal microbiota dysregulation: a pilot study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(1):59–68.

Wolff NS, Hugenholtz F, Wiersinga WJ. The emerging role of the microbiota in the ICU. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):78.

Barbier F, Pommier C, Essaied W, et al. Colonization and infection with extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in ICU patients: what impact on outcomes and carbapenem exposure? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(4):1088–97.

Sandiumenge A, Diaz E, Bodí M, Rello J. Therapy of ventilator-associated pneumonia. A patient-based approach based on the ten rules of “The Tarragona Strategy”. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(6):876–83.

Salmond GP, Welch M. Antibiotic resistance: adaptive evolution. Lancet. 2008;372:S97–103.

Liu J, Silapong S, Jeanwattanalert P, Lertsehtakarn P, et al. Multiplex real time PCR panels to identify fourteen colonization factors of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). PLoS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0176882.

Kressel AB. Contact precautions to prevent pathogen transmission. JAMA. 2018;320(4):407.

Bermejo-Martin JF, Almansa R, Martin-Fernandez M, et al. Immunological profiling to assess disease severity and prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(12):e35–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional departmental funds and Associazione Nazionale di Lotta all’AIDS (ANLAIDS) Sezione Lombarda (Italy). The present study was supported in part by institutional funding (Ricerca corrente 2019—“Extracorporeal respiratory assistance: pathophysiology, microbiology and biochemical profile for the improvement of outcome.”) of the Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Emergency, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy, and in part by funding of the Dipartimento of Fisiopatologia Medico-Chirurgica e dei Trapianti, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GG and VS equally contributed to the manuscript. Conception and design of the study: GG, VS. Acquisition of data: VS, LA, MB. Analysis and interpretation of the data: VS, GG, LA, AB. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee (Azienda Ospedaliera San Gerardo, Monza) on the 24th of September 2015, protocol #887.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Giacomo Grasselli received payment for lectures from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, Maquet, Draeger Medical and Fisher & Paykel and travel–accommodation–congress registration support from Biotest and Maquet (all these relationships are unrelated with the present work). Antonio Pesenti received payment for lectures and service on speaker bureau from Maquet and Novalung; has received consulting honorarium from Maquet and Novalung (all these relationships are unrelated with the present work). No competing interest has been declared by co-authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Methods S1.

Setting and standard of care. Table S1. Diagnostic criteria for infections. Results—Figure S1. Patients population flowchart. Table S2. Infections at admission. Table S3. Cox regression of the independent risk factors associated to the first NI. Table S4. Infection onset times.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grasselli, G., Scaravilli, V., Alagna, L. et al. Gastrointestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: effect on the risk of subsequent infections and impact on patient outcome. Ann. Intensive Care 9, 141 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0615-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-019-0615-7