Abstract

Introduction

Acquired copper deficiency myelopathy is a rare disorder associated with hematologic abnormalities, peripheral neuropathy, and sensory ataxia. Although its clinical presentation and radiographic findings are similar to other nutrient deficiencies, practitioners often fail to diagnose copper deficiency. This report describes a case of copper deficiency decades after a jejunoileal bypass (JIB) to draw attention to potential long-term sequelae associated with this now abandoned procedure.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old female presented with bilateral paresthesias of her hands and legs, accompanied by gait instability and frequent falls. The individual had a significant history of malabsorption and malnutrition related to a 40 years prior JIB for weight loss. MRI demonstrated T2 hyperintense signal in the dorsal spinal cord between C3 and C5. She was found to have copper deficiency, underwent IV repletion, prescribed oral repletion, and was discharged home. She subsequently developed progressive symptoms over the following year and remained unable to function at home. Treatment required inpatient copper repletion followed by inpatient rehabilitation. Following rehabilitation, the individual demonstrated significant improved independence.

Discussion

Although JIB surgery is not currently performed, it is important to recognize the metabolic consequences of nutrient deficiencies related to this procedure and the potential for the development of neurological sequelae including myelopathy. Furthermore, additional causes of copper deficiency to consider in cases of undifferentiated myelopathy include congenital metabolic syndromes, zinc toxicity, and malabsorption. This case demonstrates the potential of intensive physical and occupational therapy regimens, along with symptomatic treatment and nutrient repletion, to help an individual regain independence and improve activities of daily living.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Copper is an essential nutrient within the human body, necessary for the proper functioning of numerous metabolic processes. It acts as a prosthetic group in several key enzymes [1] within the bone marrow and nervous system, and thus its deficiency can result in hematologic and neurologic abnormalities [2].

In a series of 55 cases, the most common cause of copper deficiency is a previous upper gastrointestinal surgery (47% of all cases), while zinc toxicity (16%), malabsorption (15%), and iron ingestion (2%) are also potential causes. In 20% of cases, no etiology was identified [3]. Copper deficiency can manifest in a variety of ways including central nervous system demyelination [4], optic neuritis [4, 5], anemia [2], leukopenia [2], peripheral polyneuropathy [6], and lower motor neuron disease [7]. The most common neurological presentation of copper deficiency is progressive sensory ataxia related to spinal cord dorsal column involvement [8, 9]. While paresthesia and sensory ataxia related to copper deficiency in the upper and lower limbs is common, myelopathy leading to other impairments including urinary function is rare [3]. This case highlights the importance of investigating nutritional causes of myelopathy, in context with an individual’s surgical history, as well as the potential importance of rehabilitation in conjunction with nutrient repletion.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old female with history of Graves’ disease, hepatic steatosis, and chronic macrocytic anemia with unremarkable bone marrow biopsy initially presented with progressive bilateral paresthesia and gait instability. She also noted mild back pain. She was malnourished and had a 36 kg weight loss over the prior year.

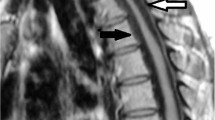

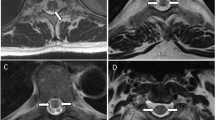

A work-up was undertaken which revealed a macrocytic anemia (hemoglobin 9.0 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume of 109 fL) and neutropenia (white blood cell count of 4200 THO/µL with 1100 THO/µL neutrophils). Vitamin B12 (891 ng/mL) and folate (19.1 ng/mL) were within normal limits. Cerebral spinal fluid studies including glucose, protein, cell count, flow cytometry, and cell culture were normal. MRI of the cervical spine revealed a T2 hyperintense signal in the dorsal spinal cord between C3 and C5 without pathologic enhancement, felt to be consistent with subacute combined degeneration (Fig. 1). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy with multiple small bowel biopsies was obtained and unremarkable.

On further work-up, she was found to have an undetectable copper level (<10 µg/dL) and a ceruloplasmin level of 5 mg/dL. She was started on copper repletion with improvement in her symptoms. Upon further discussion, she reported a “weight loss surgery” she underwent ~40 years prior to admission [10]. This was assumed and later confirmed on a small bowel follow through study to be consistent with a jejuonal bypass (JIB). She was started on oral and IV copper repletion. At that point, she was recommended to go to acute rehabilitation, but she declined.

Ten months later, the individual was admitted to an inpatient neurology service for progression of her neurologic symptoms. Since her previous discharge, she had been on oral copper repletion. Over the month prior to admission, she underwent weekly intravenous copper infusions for continued low copper levels despite oral repletion.

On admission, the individual reported progressive bilateral paresthesia in her hands and legs as well as gait instability. The bilateral paresthesia led to sensory ataxia and recurrent falls that resulted in a right rib fracture. She recently suffered a burn from hot water which she was unable to feel. The individual noted some bowel urgency but remained continent. She also reported progressive urinary urgency with episodes of urinary incontinence. She was sexually active without issues.

Repeat MRI demonstrated decreased conspicuity of the previous T2 hyperintense signal in the dorsal spinal cord (Fig. 2). Of note, an electromyography/nerve conduction study was performed and did not demonstrate a peripheral neuropathy.

During her stay, a 5-day daily course of IV copper was administered along with oral copper supplementation. At this point, she was felt to require further rehabilitation and was transferred to an acute rehabilitation hospital.

Rehabilitation course and outcome

At time of admission to rehabilitation, she reported having not been “out of the house by [her]self in 2 years.” She was noted on the right to have 4/5 strength of grip, hip flexion, dorsiflexion, and plantarflexion (otherwise 5/5) and on the left was noted to have 4/5 strength throughout with the exception of hip flexion (and knee flexion) which were graded 2/5. The individual reported decreased sensation to light touch in a glove and stocking distribution (through hands and up to knees bilaterally). She had severely impaired proprioception distally in bilateral lower extremities. She also was noted to have impaired vibration sense in bilateral upper and lower extremities (diminished in bilateral hands, absent at toes and ankles bilaterally, diminished at left knee). Furthermore, she had symmetric 1+ reflexes in bilateral lower extremities with a mute Babinski reflex on the right and downgoing Babinski reflex on the left. Bladder scans revealed that she was completely emptying her bladder.

On rehabilitation evaluation she was noted to be dependent (Functional Independence Measure (FIM) of 1) in using the stairs and ambulating and had impaired transferring ability (FIM of 3). Upon initial evaluation, she was found to have impairment in muscle tone, pain, aerobic capacity/endurance, and balance. She demonstrated poor coordination and motor control/sensation. At time of admission, she was dependent on a wheelchair for mobility.

She began intensive occupational therapy and physical therapy 5–7 times/week for 180 min duration. The interventions of occupational therapy included bilateral lower extremity active range of motion exercise, weightbearing, dynamic standing balance exercises, bilateral upper extremity hand grip/pinch strengthening, purposeful fine motor coordination therapy, and sensory integration before activities of daily living (ADLs) retraining. Physical therapy included lumbo-pelvic stability training, balance for anticipatory and reactive strategies, fear of falling and learning compensatory strategies, and sensory feedback via a mirror.

At the time of discharge, she was able to walk 300 ft at a time with a rolling walker (FIM of 5), navigate steps with handrails (FIM of 5), transfer with assistive equipment (FIM of 6) and was modified independent with all ADLs (with the exception of being unable to fasten clothing due to impaired fine motor skills).

At follow-up 1 month after discharge, the individual reported that she was doing “okay.” She continued to use a rolling walker for mobility, although was challenged by fatigue in community ambulation, particularly after busy days. She reported being independent in ADLs although still did not leave her house alone. She did not have any falls.

The individual ultimately underwent reversal of the previous JIB with take down of the jejunoileal bypass, take down of an ileocolic anastomosis and two small bowel anastomoses.

Discussion

JIB was a popular weight loss surgery in the late 1960s and early 1970s. JIB was felt to be the most effective surgical intervention for achieving and maintaining weight loss [10]. The surgery entails anastomosis of the proximal jejunum to the terminal ileum, ultimately leading to weight loss via malabsorption, essentially creating iatrogenic short bowel syndrome [11, 12]. However, this surgery is no longer performed because of its short- and long-term complications including renal failure, electrolyte imbalance, nephrolithiasis, liver disease, fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies, malnutrition, and ultimately early death [11]. There are very few people alive today with a JIB.

One of the nutritional deficiencies seen following JIB is a copper deficiency. Copper is an essential dietary micronutrient with the absorption occurring predominantly in the duodenum [13, 14]. Copper deficiency can lead to dorsal column degeneration which is indistinguishable to B12 deficiency related subacute combined degeneration [15], making diagnosis and treatment difficult. In cases with JIB, treatment of micronutrient deficiency remains challenging, as oral repletion may not be effective.

The individual in this case had initially presented with bilateral paresthesia thought to be related to an acute GI illness. As a result, multiple unremarkable laboratory tests and imaging studies were performed. She was eventually noted to have low copper and started on oral repletion although due to insufficient response, she subsequently required regular IV copper infusions. However, this therapy alone did not improve her function and she remained immobile with frequent falls. She later presented for worsening bilateral paresthesia, gait instability, and falling, in the setting of an ongoing copper deficiency and inadequate repletion. Examination of her history led to the identification of a remote history of a JIB for weight loss, which was ultimately determined to be the cause of her persistent copper deficiency despite oral repletion.

Following her most recent admission, in conjunction with PO and IV Copper repletion and appropriate pharmacological treatment, she began a 2-week intensive inpatient physical and occupational therapy regimen aimed at improving ADLs and increasing mobility. She ultimately was able to regain independence and return home with improvement in her symptoms and function and absence of falls. She did continue to have difficulty with fatigue and community mobility.

This case highlights several important lessons. For all cases of unexplained myelopathy, a thorough surgical history (particularly for bariatric surgery), as well as evaluation for nutritional deficiencies, should be undertaken. If copper deficiency is identified, other potential causes such as zinc toxicity, malabsorption, and excess iron ingestion should be investigated. Furthermore, this case highlights the central role of continued functional monitoring in those with a history of myelopathy given potential for functional decline, immobility, falls, and injury.

Finally, while gastric bypass/surgeries are well understood for their effects on vital nutrients [16, 17], to our knowledge there are no cases detailing the impact of intensive inpatient rehabilitation on an individual with copper myelopathy. Although intensive inpatient rehabilitation appears to have been beneficial in this case, we cannot exclude that increased intravenous copper repletion may solely have led to the her functional improvement. It is important for clinicians to be aware of nutritionally related myelopathies and the potential benefit of concurrent rehabilitation interventions along with nutritional supplementation.

References

Uauy R, Olivares M, Gonzalez M. Essentiality of copper in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:952s–9s.

Dunlap WM, James GW 3rd, Hume DM. Anemia and neutropenia caused by copper deficiency. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:470–6.

Jaiser SR, Winston GP. Copper deficiency myelopathy. J Neurol. 2010;257:869–81.

Naismith RT, Shepherd JB, Weihl CC, Tutlam NT, Cross AH. Acute and bilateral blindness due to optic neuropathy associated with copper deficiency. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1025–7.

Prodan CI, Holland NR, Wisdom PJ, Burstein SA, Bottomley SS. CNS demyelination associated with copper deficiency and hyperzincemia. Neurology. 2002;59:1453–6.

Plantone D, Primiano G, Renna R, Restuccia D, Iorio R, Patanella KA, et al. Copper deficiency myelopathy: a report of two cases. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:559–62.

Weihl CC, Lopate G. Motor neuron disease associated with copper deficiency. Muscle Nerve. 2006;34:789–93.

Goodman BP, Bosch EP, Ross MA, Hoffman-Snyder C, Dodick DD, Smith BE. Clinical and electrodiagnostic findings in copper deficiency myeloneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:524–7.

Kumar N. Copper deficiency myelopathy (human swayback). Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1371–84.

Singh D, Laya AS, Clarkston WK, Allen MJ. Jejunoileal bypass: a surgery of the past and a review of its complications. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2277–9.

Elder KA, Wolfe BM. Bariatric surgery: a review of procedures and outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2253–71.

Griffen WO, Young L, Stevenson CC. A prospective comparison of gastric and jejunoileal bypass procesured for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 1977;186:500–7.

Sternlieb I, Janowitz HD. Absorption of copper in malabsorption syndromes. J Clin Investig. 1964;43:1049–55.

Sternlier I, Morell AG, Bauer CD, Combes B, De Bobes-Sternberg S, Schein-Berg IH. Detection of the heterozygous carrier of the Wilson’s disease gene. J Clin Investig. 1961;40:707–15.

Schwendimann RN. Metabolic, nutritional, and toxic myelopathies. Neurol Clin. 2013;31:207–18.

Tan JC, Burns DL, Jones RH. Severe ataxia, myelopathy, and peripheral neuropathy due to acquired copper deficiency in a patient with history of gastrectomy. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2006;30:446–50.

Griffith DP, Liff DA, Ziegler TR, Esper GJ, Winton EF. Acquired copper deficiency: a potentially serious and preventable complication following gastric bypass surgery. Obesity. 2009;17:827–31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Joshi, S., McLarney, M. & Abramoff, B. Copper deficiency related myelopathy 40 years following a jejunoileal bypass. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 104 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0249-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0249-x