Abstract

In this study, we optimise two types of multi-stream configurations (a T-junction and a flow-focusing design) to generate a homogeneous extensional flow within a well-defined region. The former is used to generate a stagnation point flow allowing molecules to accumulate significant strain, which has been found very useful for performing elongational studies. The latter relies on the presence of opposing lateral streams to shape a main stream and generate a strong region of extension in which the shearing effects of fluid–wall interactions are reduced near the region of interest. The optimisations are performed in two (2D) and three dimensions (3D) under creeping flow conditions for Newtonian fluid flow. It is demonstrated that in contrast with the classical-shaped geometries, the optimised designs are able to generate a well-defined region of homogeneous extension. The operational limits of the obtained 3D optimised configurations are investigated in terms of Weissenberg number for both constant viscosity and shear-thinning viscoelastic fluids. Additionally, for the 3D optimised flow-focusing device, the operational limits are investigated in terms of increasing Reynolds number and for a range of velocity ratios between the opposing lateral streams and the main stream. For all obtained 3D optimised multi-stream configurations, we perform the experimental validation considering a Newtonian fluid flow. Our results show good agreement with the numerical study, reproducing the desired kinematics for which the designs are optimised.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

A great number of industrial and scientific fields require applications that can provide meaningful and accurate information on the mechanical properties of the fluids employed in their daily processes, which are often characterised by a complex microstructure. Microfluidic devices bring about a number of features that makes them a very attractive choice as a platform for monitoring the fluid behaviour and their mechanical properties (Oliveira et al. 2012a). Most importantly, the characteristic small-length scales which microfluidic devices operate (1–1000 \({\upmu \hbox {m}}\)) provide high surface-to-volume ratios, thus enhancing some mechanical properties of the fluids and/or samples of interest, compared to macroscale flows. This offers the ability to perform in-depth studies, such as the characterisation of the elastic behaviour of viscoelastic fluids and the investigation of responses of particles, cells, and molecules. Indeed, lab-on-a-chip devices have been recognised for their potential to provide meaningful measurements in the context of rheological studies of complex fluids (Pipe and McKinley 2009), offering advantages towards their investigation and characterisation, under both shear and extensional deformation.

For studies related to extensional rheological flows of complex fluids, several micro-fabricated designs have been suggested as promising platforms for evaluating extensional material functions such as the extensional viscosity (Galindo-Rosales et al. 2013; Haward 2016). In contrast with Newtonian fluids, for viscoelastic fluids, the flow resistance can increase dramatically and in a highly non-linear manner as the strain-rate increases (Gaudet and McKinley 1998). This makes the evaluation of extensional viscosity highly desired. However, this task has been very difficult and with limited practical success achieved (Haward 2016). The majority of the configurations proposed attempt to generate the appropriate flow conditions, by exploiting geometrical or hydrodynamic characteristics, that will result in a homogeneous extensional flow. Thus, the extension rate applied on a fluid element can ideally be considered as constant both in space and time, allowing for accurate measurements of the extensional viscosity (Walters 1975). This follows a similar principle as employed in shear rheometry, where a homogeneous shear rate is sought and measurements of the shear viscosity of a fluid are ideally performed when the flow is viscometric. Moreover, in a recent review by du Roure et al. (2019), the authors highlight the potential of well-designed configurations that offer an increased and accurate flow control in the context of studies related to the dynamics of flexible fibres.

The microfluidic designs proposed for studying extensional flows can be distinguished in two categories, namely the single-stream and multi-stream designs. The former refers to designs that control a single fluid stream employing only one inlet and one outlet such as contraction, expansion, and contraction/expansion flows (Rodd et al. 2005; Oliveira et al. 2007; Zografos et al. 2016). The term multi-stream refers to designs that manipulate more than one fluid stream by incorporating more than one inlet and/or outlet. All the designs proposed in this study belong to this latter category.

Multi-stream configurations enjoy great popularity in studies related to polymer solutions, multi-phase systems, bio-fluids, and cell responses (Haward 2016). This includes designs such as cross-slots, T-junctions, and flow-focusing configurations. To date, the use of cross-slot geometries has found great success and has been widely used both in numerical (Poole et al. 2007; Afonso et al. 2010; Cruz et al. 2016; Zografos et al. 2018) and experimental (Arratia et al. 2006; Dylla-Spears et al. 2010; Gossett et al. 2012b; Haward et al. 2012a; Burshtein et al. 2017; Abed et al. 2017) studies related to Newtonian flows, viscoelastic flows, and single-molecule/single-cell responses, due to the fact that they are able to generate strong extensional flows exploiting the presence of the stagnation point (SP). Moreover, improved counterparts have also been proposed employing optimisation techniques as potential platforms for achieving accurate rheological measurements (Alves 2008; Haward et al. 2012b; Haward and McKinley 2013; Galindo-Rosales et al. 2014).

T-junction (TJ) configurations shown schematically in Fig. 1a are considered in this study. Compared to cross-slots, their operation is simpler as there is one less stream to control. Depending on the process/application that the TJ geometry is intended for, the channels can be addressed as inlets or outlets in different ways. Here, the fluid is injected into the device by two opposing channels and is ejected through the single perpendicular channel. This stagnation point flow geometry has been used in studies related to single-molecule dynamics (Tang and Doyle 2007; Vigolo et al. 2014), flow instabilities (Miranda et al. 2008; Soulages et al. 2009; Poole et al. 2014; Matos and Oliveira 2014), micromixing (Mouheb et al. 2011, 2012), droplet generation, and other interfacial studies (Christopher and Anna 2009; Anna 2016; Chiarello et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2018; Haringa et al. 2019), and was suggested as a potential microfluidic rheometer (Zimmerman et al. 2006). However, to this day, the capabilities of these shapes for rheological purposes have not been thoroughly explored (Galindo-Rosales et al. 2013). Finally, it is mentioned that the stagnation point flow generated in TJ designs differs from that in the cross-slots. For the former, the SP is pinned at the wall, while for the latter, there is a free SP where the extension rate is finite (Haward et al. 2012a; Galindo-Rosales et al. 2013).

Another multi-stream geometry that can be employed for performing extensional flow studies is the flow-focusing (FF) design, and is shown schematically in Fig. 1b. In contrast with cross-slot and TJ configurations, the FF does not exhibit a stagnation point. The design consists of four orthogonal intersecting channels, where three operate as inlets and the last one is used as a single outlet. An important characteristic of this type of geometry is the potential to minimise the shear effects in the region of interest due to fluid–wall interactions. The fluid that is injected from the two opposing channels shapes the third stream that is introduced through the perpendicular inlet and contains the fluid of interest, generating a region of shear-free, elongational flow (Galindo-Rosales et al. 2013). The converging flow of the fluid of interest is reminiscent of the flow produced by a single-stream hyperbolic contraction channel (Oliveira et al. 2009, 2011, 2012b). An interesting advantage of the FF geometry is that different total Hencky strains can be applied using the same device. This may be achieved by simply changing the inlet velocity ratio between the lateral stream and the main stream. On the contrary, for the constrained type of flow produced in the hyperbolic designs, this can only happen with the use of different devices. The ability of FF designs to produce strong extensional flows, has been exploited in the context of extensional rheology studies (Arratia et al. 2008; Juarez and Arratia 2011). Both in Arratia et al. (2008) and Juarez and Arratia (2011), the authors reported an exponential decay of the thickness of the filament that was formed due to the interactions of the vertical and horizontal streams (see Fig. 1b). This decay was then used to evaluate the extensional viscosity of the fluids considered.

The FF microfluidic device has been mostly considered in studies related to droplet formation and investigation of the filament pinch-off for Newtonian and polymeric immiscible fluids (Steinhaus and Sureshkumar 2007; Christopher and Anna 2007; Anna 2016), in studies related to the destabilising effects of the thread formations for highly viscous miscible and immiscible fluids (Cubaud and Mason 2009) and also finds applications in drug delivery (Xu et al. 2009; Damiati et al. 2018) and in particle focusing (Xuan et al. 2010). Recently, several optimised shapes of flow-focusing devices have been proposed, which are able to generate homogeneous extensional flows in the vicinity of their geometric centreline for the purpose of studying the behaviour of \(\uplambda\)-DNA molecules under extensional flow (Pimenta et al. 2018). They showed, using Brownian dynamics simulations, that the extension of \(\uplambda\)-DNA molecules in these devices is close to that expected in an analytical planar extensional flow. They also highlighted the need of optimised configurations in rheological studies. However, no experimental verification of their optimised geometries is reported in Pimenta et al. (2018).

In summary, multi-stream configurations offer the possibility to generate strong extensional flows, which are less affected by shear (Alves 2008; Haward 2016; Pimenta et al. 2018), with the potential to achieve a better performance related to the homogeneity of the extensional field (Haward et al. 2012a; Galindo-Rosales et al. 2014; Oliveira et al. 2007; Ober et al. 2013). In addition, the versatility of being able to generate a variety of different flow conditions (e.g. variation of Hencky strain in a single flow-focusing device) has made these configurations worth exploring in the context of complex fluid flow characterisation.

In this paper, we investigate the flow kinematics in two different multi-stream configurations (T-junction and flow-focusing devices) and propose improved designs based on a numerical optimisation strategy that will be able to produce a region of homogeneous extensional flow and can be advantageous for several applications. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows: initially, the configurations under investigation are introduced and defined in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, the optimisation strategy with the ideal velocity used as “target profile” and the resulting desired strain-rates are presented. Then, the equations of motion that are solved numerically are given. The section concludes by presenting in detail the methods used in the experiments performed for validating the proposed designs. Section 4 presents the optimisation study for all multi-stream configurations considered (TJ and FF). Their performances against standard shapes are discussed, their operational limits under several cases are reported, and their experimental validations are presented. Finally, in Sect. 5, the results of this study are summarised.

2 Geometry definition

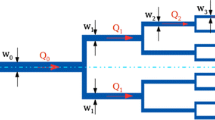

The geometries considered in this work are optimised both in 2D and 3D, and their geometrical characteristics are presented in Fig. 1 and discussed in more detail in this section. For all designs, a desired length for obtaining a region of homogeneous extension, \(L_\text {opt}\), is defined, while the widths of the horizontal segments, \(w_{1}\), are always equal to the widths of the vertical segments, \(w_{2}\). When 3D configurations are optimised, a typical square cross section is considered for all cases, resulting in an aspect ratio \(\text {AR}=d/w_{1}=1\), where d is the depth of the design.

In Fig. 1a, a “bird’s eye view” of the TJ configuration is shown. The fluid inlets are imposed by the two horizontal, opposing channels, with equal flow rates (\(Q_{1}\)). The optimisation length is correlated to the upstream width as \(L_\text {opt}=n_{1}w_{1}\), where for all cases examined in this paper for this particular design, the dimensionless factor is set as \(n_{1}=4\). Similarly, in Fig. 1b, the FF geometry is shown schematically. For this design, the fluids of interest are injected through three inlets: two opposing horizontal channels with equal flow rates (\(Q_{1}\)) and one perpendicular channel (\(Q_{2}\)) that is located exactly opposite to the only outlet channel of the device. This is arguably the most common set-up used in the literature for an FF configuration (Arratia et al. 2008; Cubaud and Mason 2009), where the widths of all channels (inlets and outlets) are set to be the same. Alternative designs have also been considered in other studies, where configurations have varying values of width ratios (Steinhaus and Sureshkumar 2007; Ballesta and Alves 2017) and different angles between the entrance channels (Gossett et al. 2012a; Shahriari et al. 2016). The length of the desired constant strain-rate region is as previously correlated to \(w_{1}\), where for the bulk of the simulations we set \(n_{1}=3\). Additionally, we assess the effect of the optimisation length on the final shape with two extra 3D cases (\(\text {AR}=1\)), considering \(n_{1}=4\) and \(n_{1}=7\). An important dimensionless number for the FF design is the velocity ratio defined as \(\text {VR}=U_{1}/U_{2}\), where \(U_{1}=Q_{1}/w_{1}d\) and \(U_{2}=Q_{2}/w_{2}d\). This parameter dictates the imposed Hencky strain, which can be approximated by \(\epsilon _{\text {H}}\simeq\ln (U_{\text {out}}/U_{2})=\ln (2{\text {VR}}+1)\), and can be varied according to the desired application.

3 Methods

3.1 Optimisation strategy

The shape optimisation strategy employed here follows the same principles of our previous work on the optimisation of 2D and 3D single-stream, converging-diverging channels of different aspect ratios, discussed in detail in Zografos et al. (2016) and in Zografos (2017). Initially, the desired velocity profiles and the expected strain-rate profiles produced are defined mathematically and then are employed as “targets”, to optimise each of the desired geometries. Recently, Suteria et al. (2019) employed one of the optimised converging/diverging channels suggested in Zografos et al. (2016) and investigated its performance. The authors proposed an “easy to use” disposable microfluidic extensional viscometer for low viscosity and weakly elastic polymer solutions, and demonstrated experimentally its very good performance compared to other experimental methodologies. The optimisation approach followed here differs from the one used in Pimenta et al. (2018), since here a more realistic smoothed velocity profile is employed, similar to those used in Zografos et al. (2016) for all cases. Also in their study for the FF geometry, Pimenta et al. (2018) allow changes to the boundary of the vertical inlet channel close to the meeting point with the lateral entrances, while here this boundary remains fixed.

Normalised velocity used as the target in the optimisations together with the resulting strain-rate that is ideally applied along the centreline of the flow at the region of interest (see Fig. 1). The arrows point to the y-axis of reference for each profile

In Fig. 2, the normalised smoothed velocity profile, \(\nu /U_{1}\), along the flow centreline (see Fig. 1) considered as the target in all optimisations is shown, where \(U_{1}\) is the average velocity at the horizontal inlets, as shown in Fig. 1. Based on our previous experience in channel optimisation, the use of a second-order continuous, smooth profile is preferred to remove any unphysical discontinuities of the abrupt profile, which are known to highly affect the optimisation procedure (Zografos et al. 2016). The desired linear velocity increment is shifted along the spatial direction, as shown in Fig. 2, in such a way that a normalised transition region \(l_{\varepsilon }/w_{1}\) is defined at the beginning of the profile. Within this region, the normalised velocity along the flow centreline follows a second-order polynomial function. The length of this transition region is correlated to the upstream width by the use of a factor \(n_{2}\), such that \(l_{\varepsilon }=n_{2}w_{1}\), and is set for all cases (both for the TJ and the FF) as \(n_{2}=0.5\). In the same way, a smoother transition region of the same span is also applied at the end of desired linear increase. The final modified smoothed velocity profile for a T-junction along the flow centreline is expressed in a general form as:

where \({\tilde{\nu }}=\nu /U_{1}\) is the streamwise normalised velocity along the flow centreline, \({\tilde{\nu }}_{d}=\nu_{d} /U_{1}\) the normalised maximum fully developed velocity at the outlet, \(f_{1}={\tilde{\nu}_{d}}/n_{1}\) and \(f_{2}={\tilde{\nu }}_{d}/2n_{1}n_{2}\). The symbols with “tilde” are only used to represent normalised quantities, such as \({\tilde{\nu }}=\nu /U_{1}\) and \({\tilde{y}}=y/w_{1}\), in Eqs. (1)–(6) to increase their readability. The resulting normalised strain-rate profile (\({\dot{\varepsilon }}=\partial {u}/\partial {x}\)) along the flow centreline experienced by a fluid element is expressed by:

The approach discussed for the TJ is applied to the velocity profile that is used as the target for the FF optimisation, following the same principles. Some minor modifications are introduced to take into account the influence of the third inlet stream:

where \({\tilde{\nu }}_{2}=\nu _{2}/U_{1}\) is the maximum normalised velocity along the flow centreline of the third vertical inlet, while the parameters \(f_{1}\) and \(f_{2}\) are now modified as \(f_{1}=({\tilde{\nu }}_{d}-{\tilde{\nu }}_{2})/n_{1}\) and \(f_{2}=({\tilde{\nu }}_{d}-{\tilde{\nu }}_{2})/2n_{1}n_{2}\). The resulting normalised strain-rate profile along the flow centreline which corresponds to Eq. (3) is expressed by:

The equations presented are valid both for 2D and 3D flows. The maximum normalised velocities along the flow centreline at the start and end of the region of interest \({\tilde{\nu }}_{2}\) and \({\tilde{\nu }}_{d}\) are required for constructing the appropriate optimisation profiles and depend on the aspect ratio considered. We set their values by evaluating the fully developed velocity at the centreline (\(y=0\), \(z=0\)) using the analytical profile for a duct with a rectangular cross section as given in White (2006):

where Q is the channel’s flow rate.

The optimisation procedure is an iterative operation schematically described in the flowchart of Fig. 3. It combines an automatic mesh generation routine, a fluid flow solver, and an optimiser. This procedure provides the ability to determine numerically the appropriate boundary shape of the device for obtaining a flow field with the desired characteristics as defined in Eq. (1) for the TJ and Eq. (3) for the FF. Here, we follow the same approach as in Zografos et al. (2016), and a more detailed discussion regarding the use of the current procedure can be found in Zografos (2017). Briefly, we use the freely available derivative-free optimiser NOMAD (Le Digabel 2011; Audet and Dennis 2006; Audet et al. 2009), which is based on the Mesh Adaptive Direct Search algorithm and is appropriate for performing non-linear constrained optimisations. The deformation of the structured grid that discretises the geometry of interest is achieved by a numerical procedure that is based on the geometrical deformation of an object using the Non-Uniform Rational B-Splines (NURBS), a technique that was introduced by Lamousin and Waggenspack (1994). According to this procedure, an external lattice consisting of a desired number of control points initially embeds the numerical grid and is responsible for the desired deformation of the physical domain. More specifically, an initial estimate \(\mathbf {Y^{0}}\) which corresponds to the lattice design-points’ starting positions is given as an input (see Fig. 3) and a first deformation is applied to the numerical grid that discretises the desired geometry. The flow field within the design is then evaluated by a CFD simulation and an initial value of the objective function, \(F_{\text {obj}}(\mathbf {Y^{0}})\), is calculated. The value of each objective function is evaluated as a cell-average velocity difference between the ideal behaviour (desired target profile) and each CFD outcome as:

where \({\tilde{\nu }}_{\rm {target},i}\) is the desired dimensionless velocity value required at the centre of each computational cell i (expressed in Eqs. (1) and (3) for a TJ or an FF, respectively). Moreover, in Eq. (6), \({\tilde{\nu }}_{i}\) is the dimensionless velocity evaluated from the CFD solver at each i-cell along the centreline of the flow, while \(\Delta {\tilde{y}}_{i}\) is the streamwise dimensionless spacing of the computational cell i. After \(F_{\text {obj}}(\mathbf {Y^{0}})\) is obtained, a new estimate with a set of spatial coordinates \(\mathbf {Y^{*}}\) is generated, which corresponds to the new positions of the lattice design points. For each movement of any of the lattice points, a deformation of the numerical mesh is applied via the NURBS deformation lattice. After the geometry is deformed, the flow solver simulates the flow within the new geometry from which a new value of a single objective function, \(F_{\text {obj}}\), is calculated. This process is repeated and each obtained \(F_{\text {obj}}(\mathbf {Y^{*}})\) value is examined by the optimiser. The aim of the optimiser is to approximate the desired velocity profile and this is achieved by minimising Eq. (6). When a minimum value for \(F_{\text {obj}}\) is approached, the final optimised solution \(\mathbf {Y^{\text {opt}}}\) is obtained and the final optimised physical domain is produced; otherwise, a new set \(\mathbf {Y^{n+1}}\) of locations is automatically produced by the optimiser and the procedure is repeated. Here, every \({\mathbf {Y}}\) corresponds to a set of x and y coordinates that result in a movement along a radius R, as indicated schematically in Fig. 1.

3.2 Governing equations

The CFD simulations performed for each evaluation of the objective function consider a laminar, incompressible, and isothermal fluid flow. Therefore, the continuity and the momentum equations given below are discretised and solved numerically:

where \(\pmb {\text {u}}\) the velocity vector, \(\rho\) is the fluid density, p is the pressure, and \(\pmb {\tau }\) corresponds to the extra-stress tensor. The latter is defined as the sum of the solvent stress component, \(\pmb {\tau }_{s}\) (Newtonian part), and the polymeric stress component \(\pmb {\tau }_{p}\):

where \(\eta _{s}\) is the solvent viscosity. Equation 9 is valid for viscoelastic fluids and reduces to \(\pmb {\tau } = \eta _{s}(\nabla \pmb {\text {u}}+\nabla \pmb {\text {u}}^{T})\) for Newtonian fluids when \(\pmb {\tau }_{p}=0\).

In this study, we are interested in using both the TJ and the FF configurations for potential applications in microfluidics for which creeping flow conditions (\(\text {Re}\rightarrow 0\)) are a good approximation. Therefore, the optimisations are performed under such conditions for which the convective term in the momentum equation can be considered negligible (\(\pmb {\text {u}}\cdot \nabla \pmb {\text {u}}\rightarrow 0\)). Additionally, since we aim to propose general designs that are able to generate the ideal/desired flow kinematics, we search for the most efficient solutions employing a Newtonian fluid flow as our base flow. Once the appropriate design is found, its operational limits are then investigated in terms of Weissenberg numbers (\(\text {Wi}\)) for viscoelastic fluids. For the case of the FF optimised configuration, an investigation of the design limits in terms of increasing Reynolds numbers for Newtonian fluids is also performed and the full momentum equation is solved. The Reynolds number is defined here as \(\text {Re}=\rho U_{\text {out}}w_{2}/\eta _{0}\), where \(\eta _{0}\) corresponds to the zero shear total viscosity, \(\eta _{0}=\eta _{s}+\eta _{p}\), defined as the sum of the solvent and the polymer viscosity \(\eta _{p}\) (for Newtonian fluids \(\eta _{p}=0\)) and \(U_{\text {out}}\) is the average velocity at the outlet channel. When viscoelastic fluid flow is considered, the Weissenberg number used to characterise the effects of viscoelasticity is defined as \(\text {Wi}=\lambda U_{\text {out}}/w_{2}\).

The response of viscoelastic fluids is investigated by considering the Oldroyd-B model (Bird et al. 1987) and the linear form of the simplified Phan–Thien and Tanner model (sPTT) (Phan-Thien and Tanner 1977). The former exhibits a constant shear viscosity, and therefore, it is used here to investigate the effects of elasticity alone, whereas the latter is employed because of its additional ability to predict shear-thinning behaviour. Both models are expressed here considering the compact form of the evolution of the conformation tensor, \(\mathbf A\) (Afonso et al. 2009):

where \(\overset{\triangledown }{\mathbf{A }}\) is the upper convected derivative of the conformation tensor, \(\lambda\) is the relaxation time of the polymer, and \(\mathbf I\) is the identity tensor. For the sPTT model, the function \(f_{A}\) in Eq. (10) is a function of the trace of the conformation tensor, expressed as (Oliveira 2002; Afonso et al. 2009):

where \(\varepsilon\) corresponds to the extensibility parameter, which is responsible for the elongational properties of the fluid and sets an upper bound for the extensional viscosity (Phan-Thien and Tanner 1977; Oliveira and Pinho 1999; Alves et al. 2001). At the limiting case of \(\varepsilon =0\), \(f_{A} = 1\) and Eq. (10) reduces to the expression of the Oldroyd-B model for the conformation tensor, (Oliveira 2009) for which the extensional viscosity becomes unbounded (Bird et al. 1987). Once the values of the conformation tensor are evaluated, the polymeric component of the extra-stress tensor (see Eq. (9)) is obtained from Kramers’ relationship:

The ratio of the solvent viscosity (\(\eta _{s}\)) to the total zero shear viscosity (\(\eta _{0}\)), commonly known as solvent-to-total-viscosity ratio, \(\beta\), is set to \(\beta =0.50\) for the Oldroyd-B model, which is a representative value for a constant-viscosity Boger fluid. For the sPTT model, we consider \(\beta =0.01\) and \(\varepsilon =0.25\), to represent relatively high concentration, shear-thinning polymer solutions.

The discretised set of partial differential equations (Eqs. (7) and (8)) are solved using an in-house implicit finite-volume CFD solver, developed for collocated meshes, which is described in detail in Oliveira et al. (1998) and Oliveira (2001). The viscoelastic fluid flow is evaluated using the log-conformation approach (Fattal and Kupferman 2004) which solves the evolution of the logarithm of conformation tensor (Eq. (10)), within a finite-volume methodology, as described in detail in Afonso et al. (2009, 2011). The pressure and velocity fields are coupled using the SIMPLEC algorithm for collocated meshes by employing the Rhie and Chow interpolation technique (Rhie and Chow 1983). Finally, the convective terms both in the momentum and the stress constitutive equation are discretised using the CUBISTA high-resolution scheme (Alves et al. 2003), while all diffusive terms are evaluated with central differences.

3.3 Experimental methods

To validate the numerical optimisations of the TJ and FF geometries, an example of each was fabricated and tested experimentally using micro-particle image velocimetry (\(\mu\)-PIV) to quantitatively measure the Newtonian flow field.

The experimental TJ and FF test devices were fabricated in poly(dimethyl siloxane) by standard soft lithography methods (Tabeling 2005) and mounted on a glass slide by plasma bonding. As templates for the microfluidic geometries, we used the result of a 3D optimisation for channels with aspect ratio \({\text{AR}} = 1\). The TJ geometry was optimised over a region spanning \(L_{\text {opt}} = 4w_{1}\) and the FF geometry was optimised over \(L_{\text {opt}} = 3w_{1}\). In both cases, the straight sections of channel upstream and downstream of the optimised region were of dimensions \(w_{1}=w_2=d=100 \pm {2}\,{\upmu \hbox {m}}\) (i.e., \(\text {AR}=1\)). The errors in the cross-sectional dimensions were estimated by making measurements on a number of channels sacrificially sliced through xz- and yz-planes.

a Strain-rate profiles along the centreline of the flow (obtained under creeping flow conditions) at the outlet of a \({90}^{\circ }\) sharp bend configuration, together with a rounded and a hyperbolic shaped T-channel designed for \(L_{\text{opt}}=4w_{1}\). b All common geometries are shown schematically together with the location of the stagnation point (SP) and the flow centreline (dashed line) where the profile in a is evaluated

Deionised water (density \(\rho _f \approx {1}\,{\hbox {kg m}}^{-3}\) and viscosity \(\eta \approx {0.9\,\hbox {m Pa s}}\) at 25 \(^{\circ }\)C) is used as a Newtonian test fluid to check the performance of the numerical optimisations. Flow through the microfluidic devices is driven by injecting fluid at the inlets at controlled flow rates using high-precision neMESYS syringe pumps of the low pressure and 29:1 gear ratio type (Cetoni GmbH). Hamilton gastight syringes of appropriate volumes are selected to ensure that the specified pulsation-free minimum dosing rate is always exceeded. In both the TJ and FF devices, a range of flow rates \(0.01 \le Q_{1} \le {1}\,{\upmu \hbox {Ls}}^{-1}\) is applied, and in the FF device, a range of velocity ratios \(1 \le \text {VR}\le 100\) is examined. The Reynolds numbers, based on the average outlet flow velocity \(U_\text {out}\), are in the range \(0.2 \lesssim \text{Re} \lesssim 20\). Although the geometries are optimised considering creeping flow conditions (\(\text {Re}\rightarrow 0\)), which may be a reasonable approximation in microfluidic flows, examining a range of Reynolds numbers allows us to quantify experimentally the operational limits of the proposed configurations.

Quantitative flow velocimetry in the microfluidic geometries is performed using a volume illumination \(\mu\)-PIV system (TSI Inc.) (Meinhart et al. 2000; Wereley and Meinhart 2005). For these measurements, the fluid is seeded with a low concentration (approximately 0.02 wt%) of fluorescent micro-particles (Fluoro-max, Thermo Scientific) with diameter \(d_{p}={0.5}\,{\upmu \hbox {m}}\), density \(\rho _{p} = {1.05}\,{\hbox {kg m}}^{-3}\), and peak excitation/emission wavelength \(542/{612} \,{\hbox {nm}}\). The microfluidic device is placed on the imaging stage of an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti). The midplane of the device (\(z=d/2\)) is located and brought into focus using a \(20 \times\) objective lens (numerical aperture \({\text {NA}}=0.45\)). The fluid is illuminated by a \({60}\,{\hbox {W}}\) dual-pulsed Nd:YLF laser (Terra PIV, Continuum Inc.) with wavelength \({527}\,{\hbox {nm}}\), pulse width \(\approx {10}\,{\hbox {ns}}\), and time gap between pulses \(\Delta t\), which excites fluorescence of the seeding micro-particles. Images of the fluorescing particles are captured in pairs, in synchronicity with the pairs of laser pulses, using a high-speed imaging sensor (Phantom Miro, Vision Research) operating in frame-straddling mode. Each pair of images is binned into \(32 \times 32\) pixel interrogation areas and cross-correlated using a standard \(\mu\)-PIV algorithm (implemented on Insight 4G software, TSI, Inc.). This processing yields velocity vectors u and v in the x- and y-directions, respectively, spaced on a \(6.4 \times 6.4~\upmu\)m grid. Since under all imposed conditions, the flow remains steady, 50 image pairs are captured at each flow rate and ensemble averaged, reducing noise.

For comparison between the experimental and numerical velocity fields (discussed in Sects. 4.1.5 and 4.2.6), we extract the streamwise velocity component along the centerline of the region of interest. We note that with the specified combination of objective lens and fluorescent particles, the measurement depth over which micro-particles contribute to the determination of velocity vectors is \(\delta z_m \approx 13~\upmu\)m (i.e., \(\approx 0.13d\)) (Meinhart et al. 2000). Due to the averaging over this measurement depth, some uncertainty in precisely locating the midplane with the microscope objective, and also the parabolic velocity profile through the channel depth, it is expected that the measured streamwise flow velocity at the midplane will always be slightly below the numerically computed value. In addition, due to the small uncertainty in the precise channel dimensions, an error of \(\pm\; 0.05U_\text {out}\) is estimated on the streamwise vector component. However, since the particle Stokes number \(\text {St} = \rho _{p} d_{p}^{2} \text {Re}/ 18 \rho _{f} w_{2}^{2} < 10^{-4}\) over the range of \(\text {Re}\) examined, we consider that they trace streamlines with negligible error (McKeon et al. 2007).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 T-Junction configuration

The flow in T-junction configurations as described in Sect. 2 and shown in Fig. 1a is examined here. As mentioned, the inlets and outlet are set to have equal widths. By imposing the same flow rate \(Q_{1}\) in each of the inlets (equal average velocity, \(U_{1}\)), then \(U_{\text {out}}=2U_{1}\) (\(d=\text {const}\); \(w_{1}=w_{2}\)). Before presenting the results of our optimisation study, the performance of three typical designs of T-shaped channels that are commonly used are investigated, considering a 2D flow of a Newtonian fluid under creeping flow conditions: a \({90}^{\circ }\) sharp bend configuration, a rounded configuration, and a hyperbolic configuration. Then, the enhanced performance of the 2D optimised geometry is discussed, while afterwards the optimised design proposed when taking into account 3D effects is presented and validated against experimental measurements. In addition, the efficiency of the 3D TJ for use with viscoelastic fluids is discussed in terms of increasing Weissenberg numbers.

4.1.1 Performance of common T-junction configurations

The performance of several common configurations (sharp bend, rounded, and hyperbolic) in terms of the strain-rate profile along the flow centreline, is illustrated in Fig. 4. In particular, Fig. 4a shows the obtained normalised profiles against the target strain-rate profiles (both the abrupt and the modified are included for comparison). In Fig. 4b, the investigated shapes are schematically illustrated, where the location of the stagnation point (SP) and the flow centreline (dashed-line) are indicated. It can be seen that for the \({90}^{\circ }\) sharp bend TJ, the strain-rate along the flow centreline increases rapidly to a maximum upstream value attained around the geometrical centre point of the design (\(y/w_{1}\simeq 0.5\)), deviating \(\sim 380\)% from the desired value, followed by a sudden decay without exhibiting a region of constant strain-rate. In Fig. 5a, the contours of the y-velocity component within the \({90}^{\circ }\) sharp bend configuration are shown and it is clear that the region of interest is reduced to a very narrow section where the channels intersect, resulting in the described sudden changes of the velocity field.

To investigate the case of a rounded geometry, the boundary of the configuration is constructed by considering a radius \(R=3w_{1}\), as shown in Fig. 5b. In the same figure, the contour plot of the normalised obtained solution for the y-component of the velocity is depicted. On the other hand, the equivalent solution for the hyperbolic configuration is shown in Fig. 5c, where the shape of the boundary is designed using a function equivalent to that considered in Oliveira et al. (2007) for single-stream designs.

As shown in Fig. 4, the round and hyperbolic geometries present a better performance than the abrupt configuration in terms of homogeneity of the strain-rate in the region of interest. However, the profiles still exhibit considerable fluctuations around the desired constant strain-rate profile, with a local overshoot clearly visible (maximum deviation of \(\sim 33\)% for the rounded configuration; \(\sim 29\)% for the hyperbolic geometry).

4.1.2 Optimised T-junction in 2D

In this section, the results of the optimisation procedure for a 2D TJ configuration are presented. The mesh M0 (see Table 1) is employed for the optimisations. Figure 6 illustrates the obtained optimised shape together with the normalised contour plot of the y-velocity component and the achieved performance along the flow centreline. The optimised geometry exhibits smooth salient corners in the transition boundaries between the inlet and the outlet, similar to those encountered in the OSCER device (Haward et al. 2012b). The presence of the salient corners, widen the device locally and minimise the developed velocity and shear effects in the region of interest, yielding a better approach to the desired kinematics. This is verified by the normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline shown in Fig. 6b. It can be clearly seen that both the evaluated normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles approximate very well the desired target profile employed for the optimisation, without the drawbacks discussed when common shapes are employed. The strain-rate overshoot is significantly minimised for the optimised geometry, where a minor deviation of \(\sim 4\)% for the maximum value is reported. The dependence of the optimised solution on the numerical mesh was assesed by comparing the results obtained with the mesh M0 used in the optimisation procedure, and those obtained employing a more refined mesh M1 for each of the configurations. The characteristics of both numerical meshes are given in Table 1 and a maximum negligible deviation (less than 1%) was found between the strain-rates along the flow centreline for both meshes.

Shape and performance of the optimised 2D T-junction: a Contour plots of the normalised y-component of the velocity and b normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles along the centreline of the flow in the region of interest of the optimised T-junction in 2D with \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\). The optimisation is performed considering creeping flow conditions when the modified target velocity profile of Eq. (3) is used. The dashed straight line in a illustrates the position of the symmetry plane

It is noted that instead of using a smoothed transition profile, we could have used an abrupt target velocity profile, but this would impose an instantaneous, unrealistic, step change in the strain-rate. Employing this as target can be inherently challenging to optimise the geometry both at the beginning and at the end of the desired homogeneous extension region and could produce shapes with more exaggerated salient corners (Zografos et al. 2016). An alternative to overcome the challenges associated with the non-continuous velocity gradient at the start of the region of interest would be to include a cavity, as used by Soulages et al. (2009). This particular case was found to be efficient in some situations and more information can be found in Supplementary Material.

4.1.3 Optimised T-junction in 3D

Shape and performance of the 3D optimised T-junction (\(\text {AR}=1\), \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\)): a Contour plot of the normalised y-component of the velocity and b velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline in comparison to the 3D geometry with \(\text {AR}=1\) designed using the 2D optimised boundaries, under creeping flow conditions. The dashed straight line in a illustrates the position of the symmetry plane, while the inset figure in b provides a comparison in bird’s eye view of the 3D and 2D optimised shapes

Microfluidic platforms are typically fabricated with low or moderate depths, and therefore, one needs to take into account the influence of the walls and the three-dimensional effects due to these interactions. In such cases, since the flow dynamics are expected to be different, it is anticipated that the optimised shapes obtained for 2D flows will not be adequate (Galindo-Rosales et al. 2014; Zografos et al. 2016; Pimenta et al. 2018; Zografos 2017). Therefore, the optimised shape presented in the previous section is valid only for 3D geometries where the kinematics at the centreline can be well approximated by a 2D flow field as in the core of geometries with high \(\text {AR}\) (Haward et al. 2012b; Zografos et al. 2016; Zografos 2017) (see in Supplementary Material the relative discussion). To investigate the three-dimensional effects due to fluid–wall interactions on the optimised shape of the TJ, a typical case of a geometry with a square cross section (\(\text {AR}=1\)) is examined. For the optimisations, only a quarter of the geometry was considered by applying symmetry conditions along xy- and yz-flow centreplanes, to reduce the computational cost for each three-dimensional CFD evaluation needed to be performed by the optimiser.

Figure 7a shows the optimised shape and the contour plot of the normalised y-component of the velocity, obtained from the optimisation cycle. In Fig. 7b, the performance of the optimised 3D geometry is shown, where it can be seen that the desired velocity and strain-rate profiles are very well approached, with the latter demonstrating a maximum deviation of \(\sim 1.5\)% in the core of the profile. In addition, the performance of a 3D geometry with its boundaries designed to have the shape obtained from the 2D optimisation (shown in Fig. 6a) is included for comparison. It can be seen that the 2D shape when applied to a 3D geometry with \(\text {AR}=1\) is not generating the desired response, with the results obtained demonstrating an under-prediction of the target velocities along the majority of the flow centreline (maximum deviation of \(\sim 10\)% in the core of the profile), displayed in Fig. 7b. This obviously affects the strain-rate profile, where the velocity gradient does not remain constant along the flow centreline, resulting in a maximum deviation of \(\sim 15\)%. This behaviour verifies our initial assumption that optimisations need to be performed to obtain a better approximation to the required behaviour for \(\text {AR}=1\), where 3D effects are important.

Effect of \(\text {Wi}\) on the normalised velocity together with the resulting strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline, for the optimised T-junction with \(\text {AR}=1\), \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) under creeping flow conditions, for a the Oldroyd-B model (\(\beta =0.50\)) and b the sPTT model (\(\varepsilon =0.25\) and \(\beta =0.01\)). Note that for b, \(\nu\) has been normalised with \(\nu _{d,\text {fd}}\), while the inset demonstrates the velocity profile when the standard normalisation is used and the influence of the shear-thinning behaviour is obvious

The 3D optimisations were executed by employing the numerical grid M0 (details in Table 2). As in the 2D case, the dependence of the numerical solution on the mesh refinement is evaluated with the use of the more refined mesh M1 (Table 2), where it was found that the maximum deviation in the evaluation of the strain-rates between the two meshes is less than 1%.

4.1.4 Performance of the 3D optimised TJ for increasing Weissenberg numbers

The performance of the 3D optimised T-junction when considering the flow of viscoelastic fluids for increasing values of the Weissenberg number is investigated here. The viscoelastic fluid flow is described by the Oldroyd-B and sPTT models (see in Sect. 3.2), where for the former, the solvent-to-total viscosity ratio is set to be \(\beta =0.50\) (\(\varepsilon =0\) in Eq. (11)), while for the latter, we consider \(\beta =0.01\) and \(\varepsilon =0.25\).

Figure 8 shows the computed velocity and strain-rate profiles for increasing \(\text {Wi}\) for both cases. For the Oldroyd-B model shown in Fig. 8a, it can be seen that the evaluated velocity along the centreline of the flow follows the desired behaviour of the target profile in the majority of the homogeneous extension region. More specifically, the optimised TJ performs well up to \(\text {Wi}=1.0\), with the core of the strain-rate profile being well approximated (maximum deviation smaller than \(\sim 6\)%). Further increases in \(\text {Wi}\) result in a velocity profile that starts to deviate further from the target, affecting the produced strain-rate (maximum deviation \(\sim 12\)%).

The cases examined for the sPTT model shown in Fig. 8b demonstrate a different behaviour due to the shear-thinning behaviour. Note that to take into account the influence of the shear-thinning in the velocity profiles, they are normalised using the maximum value of the fully developed velocity downstream in the outlet channel \(\nu _{d,\text {fd}}\) and not the average velocity as was done so far (Alves et al. 2003). The obtained velocities along the flow centreline clearly start to deviate above \(\text {Wi}=0.2\), but the flow can be considered fairly homogeneous up to \(\text {Wi}=0.4\). For this value, the maximum deviation in the strain-rate is \(\sim 10\)%. Further increases in \(\text {Wi}\) result in larger deviations of the velocity field, where the formation of an overshoot is encountered, resulting to the obtained deviation of the strain-rate (up to \(\sim 22\)% for \(\text {Wi}\)=1.5). The inset figure of Fig. 8b shows the obtained velocity profile when the standard normalisation is used, where the shear-thinning effect upon the velocity profile is now obvious for increasing \(\text {Wi}\). Moreover, to quantify the influence of shear-thinning within the optimised TJ without accounting the effects of viscoelasticity, the flow of the inelastic Power-law (PL) fluid (Bird wt al. 1987; Morrison 2001) was employed. The responses of the two cases are compared in detail in Supplementary Material.

The results presented above demonstrate that care needs to be taken when \(\text {Wi}>1.0\), since the evaluated strain-rates start to deviate significantly when compared to the Newtonian case. Such flow modification is a typical precursor to the onset of elastic instabilities (Haward et al. 2012b; Haward 2016). Under these conditions, the optimised channels will no longer be appropriate for rheological measurements, but can be considered as potential platforms for the investigation of elastic instabilities.

4.1.5 Experimental validation of the 3D optimised T-junction

In this section, we assess the experimental performance of the 3D optimised TJ. Several flow rates have been considered for a Newtonian fluid flow within the range \(0.2\lesssim \text {Re}\lesssim 20\). That way, the efficiency of the design operating both under conditions of creeping flow and low inertial flow is investigated, as shown in Fig. 9. It can be seen that for all the cases investigated, the experimental profiles slightly under-predict the numerical results (as expected, see Sect. 3.3), but, overall, a good performance is obtained, with the experiments producing a velocity field along the flow centreline that approximates well the desired behaviour. The maximum under-prediction of the desired theoretical response corresponds to the case of \(Q_{1}={0.1}\,{\upmu \hbox {L}}/\hbox {s}\) and was found to be smaller than 10%, evaluated at the outlet of the optimised region. The inset figure of Fig. 9 illustrates a bird’s eye view of the optimised TJ microchannel that is employed in the experiments. The boundary of the optimised numerical geometry is superimposed, demonstrating the good quality of the fabrication.

4.2 Flow-focusing configuration

The flow-focusing multi-stream configuration is optimised and investigated here (see Sect. 2; illustrated in Fig. 1b). The average velocity U1 imposed in the two horizontal inlets is the same, and the velocity ratio is set to \({\text {VR}}=U_{1}/U_{2}=20\) for the bulk of the optimisations. Initially, the 2D case is investigated, and then, the 3D optimal design for a typical square cross section (\(\text {AR}=1\)) is presented, both obtained from optimisations under creeping flow conditions. The limits of the 3D configuration are examined numerically beyond the condition for which it was optimised, including increasing \(\text {Re}\) and increasing \(\text {Wi}\) values. Additionally, its performance is evaluated numerically and validated experimentally for various velocity ratios. Furthermore, the effects on the design in terms of optimisation length are also reported.

Contour plots of the normalised y-component of the velocity with superimposed streamlines for a the \({90}^{\circ }\) standard flow-focusing shape; b the optimised 3D flow-focusing shape with \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\). c Velocity and strain-rate profiles along the centreline of the flow at the region of interest of the standard and optimised shapes

4.2.1 Optimised flow-focusing in 2D

The 2D optimisations of the flow-focusing design are performed using the numerical grid M0 (details in Table 3) for a geometry with \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\). For the CFD simulations carried out at each evaluation step, half of the geometry is considered by applying symmetry boundary conditions along the y-direction, to reduce the computational time needed to reach a good approach of the desired geometry.

Figure 10 demonstrates a comparison between the obtained optimised design and the equivalent standard shape (two sharp intersecting segments at \(90^{\circ }\)) for the same velocity ratio (VR = 20). More specifically, Fig. 10a shows the superimposed streamlines on the contour plots of the normalised velocity magnitude within the standard shape for a Newtonian fluid flow, while in Fig. 10b, the equivalent behaviour produced by the optimised design is presented. In Fig. 10c, the velocity and strain-rate profiles obtained along the centreline of the flow of each geometry are compared, both plotted against the desired target profiles (Eqs. (3) and (4)). For the standard FF configuration, the velocity along the flow centreline rapidly increases to its maximum value, similarly to what was seen for the TJ case. As a result, the strain-rate profile along the flow centreline is not constant, but rather peaks just downstream of the geometrical centre of the design and then decays very rapidly. On the other hand, the optimised shape generates a velocity profile along the flow centreline that approaches very well the desired velocity target, producing a large region of homogeneous strain-rate as desired. The obtained strain-rate has a maximum deviation of \(\sim 4\%\), located immediately after the smoothing transition region. Observing now the streamlines along the centreplane of each configuration (cf. Fig. 10a, b), it can be seen that the horizontal streams of the standard geometry highly compress the vertical incoming stream. This behaviour is akin to that produced by an abrupt contraction. On the contrary, the optimised geometry produces a flow that resembles the one obtained by a smooth contraction, in which transitions are not sudden and the desired profiles are easier to generate.

a Velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline of the optimised 2D flow-focusing geometry (\(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) and \(\text {VR}=20\)) under creeping flow conditions when imposing different velocity ratios. b Shape comparison of the optimised geometries with \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) when considering different velocity ratios in the optimisation. The dashed straight line in b illustrates the centreline of the flow where profiles are extracted

Shape and performance of the optimised 3D flow-focusing: a Contour plot of the normalised velocity magnitude and b velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline of the optimised FF in 3D with \(\text {AR}=1\), \(\text {VR}=20\), \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\). The dashed straight line in a illustrates the centreline of the flow and the symmetry axis, while the inset figure in b provides a comparison in bird’s eye view of the 3D and 2D optimised shapes

In this type of configuration, one is able to exploit the advantage of testing a range of different Hencky strains in a single device by changing the velocity ratio (Oliveira et al. 2009, 2011, 2012b). Therefore, to investigate the performance of the geometry optimised for \(\text {VR}=20\) when different velocity ratios are employed, we analyse the flow behaviour in this geometry when imposing \(\text {VR}=10\) and \(\text {VR}=100\). Figure 11a shows that the desired strain-rate profile is slightly over-predicted for the case of \(\text {VR}=10\) and slightly under-predicted for the case of \(\text {VR}=100\); however, it remains within the well-defined operational limits with a small maximum deviation in the evaluated strain-rates that is less than 2.5%. This can be further supported by the results obtained when performing additional optimisations for the same geometrical configuration for the cases with \(\text {VR}=10\) and \(\text {VR}=100\). As shown in Fig. 11b, when the velocity ratio is increased, the differences between the shapes tend to be smaller. The salient corners formed at the boundaries of the junction region are gradually being smoothed and the resulting shape at the start of the transition region is wider. On the contrary, for the cases with the smaller velocity ratio (\(\text {VR}=10\)), in which the fluid going through the central inlet is subjected to a smaller strain, more abrupt changes occur in the optimised boundary of the design to approach the desired target. The dependence of the obtained numerical results on the numerical mesh is examined by considering a more refined mesh M1 (details given in Table 3). It was found that the maximum deviation between the two meshes is approximately 1.2% for the cases of \(\text {VR}=10\) and 20 and less than 1% for the case of \(\text {VR}=100\).

4.2.2 Optimised flow-focusing in 3D

The 2D optimised shape presented for the FF is not necessarily the best choice for 3D devices that are characterised by moderate values of depth, similarly to what was seen before for the T-junction. This was also shown in Pimenta et al. (2018), where the authors obtained different designs for a range of different aspect ratios. In the present work, the configuration of an FF geometry with an aspect ratio of \(\text {AR}=1\) is optimised and presented here (\(\text {VR}=20\); creeping flow), considering the target velocity profile is evaluated using Eq. (5). As in all optimisations so far, only a quarter of the full geometry is employed by applying symmetry conditions along xy- and yz-centreplanes (mesh M0; details in Table 4) to minimise the computational costs.

The 3D optimised shape for \(\text {AR}=1\) is shown in Fig. 12a, together with contours of the normalised velocity magnitude. In Fig. 12b, the normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline produced by the optimised geometry are given, in comparison with the desired target profiles. A maximum deviation of \(\sim 1\)% from the target response is reported in the core of the strain-rate profile, demonstrating a very good approximation to the desired performance. The numerical results and, therefore, the produced optimised shape for this case were found to be mesh independent, since the maximum deviation of the strain-rates between meshes M0 and M1 employed for this purpose (details in Table 4) is less than 1%.

4.2.3 Performance of the 3D optimised FF geometry for increasing Reynolds numbers

In this section, we report the operational limits of the 3D configuration with \(\text {AR}=1\) in terms of increasing Reynolds numbers considering Newtonian fluid flow (\(\text {VR}=20\) for all cases).

Figure 13 demonstrates the performance of the design for increasing Reynolds numbers. It can be seen that the configuration is able to approximate very well both the normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles up to \(\text {Re}=2\). In particular, for the strain-rate response, a maximum deviation of \(\sim 2\%\) is reported at the core of the profile. For further increases in Reynolds numbers, the obtained velocity responses start to deviate from the desired profile due to inertial effects. In terms of the strain-rate, however, larger deviations appear mostly in the transition region with the profile being slightly shifted, but remaining relatively constant along the desired constant region (small under-prediction of \(\sim 4\%\) in the core). The core of the strain-rate profile starts to be affected for further increases above \(\text {Re}=10\), under-predicting the desired response by approximately \(8\%\). Thus, for \(\text {Re}\ge 10\), a different design should be proposed to take into account inertial effects.

Effect of \(\text {Wi}\) on the normalised velocity and the resulted strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline, for the optimised flow-focusing geometry with \(\text {AR}=1\), \(\text {VR}=20\), \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) under creeping flow conditions, for a the Oldroyd-B model (\(\beta =0.50\)) and b for the sPTT model (\(\varepsilon =0.25\) and \(\beta =0.01\)). Note that for b, \(\nu\) has been normalised with \(\nu _{d,\text {fd}}\), while the inset demonstrates the velocity profile when the standard normalisation is used and the influence of the shear-thinning behaviour is obvious

4.2.4 Performance of the 3D optimised FF for increasing Weissenberg numbers

The performance of the 3D optimised FF configuration is reported here considering the flow of viscoelastic fluids. The effects of elasticity are examined employing as previously (see Sect. 4.1.4) a constant viscosity viscoelastic fluid of a moderate concentration (Oldroyd-B model with \(\beta =0.5\)) and a highly concentrated, shear-thinning viscoelastic fluid (sPTT model with \(\varepsilon =0.25\) and \(\beta =0.01\)).

Figure 14a shows the normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles obtained along the flow centreline of the optimised FF for the Oldroyd-B model. For both profiles, it can be seen that the desired behaviour is attained for the majority of the optimised region up to \(\text {Wi}=0.4\). For further increases in \(\text {Wi}\), the core of both profiles starts to deviate from the desired response. When \(\text {Wi}=1.5\), the strain-rate is under-predicted resulting in a maximum deviation of \(\sim 16\%\), while additionally a strain-rate overshoot is formed after the first transition region, as a consequence of the presence of the vertical stream.

Performance and shapes of the optimised 3D flow-focusing designs: a Normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles along the centreline of the flow in the region of interest with different lengths (\(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(L_\text {opt}=7w_{1}\)) and contour plots of the normalised velocity magnitude for b \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and c \(L_\text {opt}=7w_{1}\). For all cases, the optimisation is performed considering creeping flow conditions employing Eq. (3) as target velocity profile, for \(\text {AR}=1\), \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) and \(\text {VR}=20\). The dashed straight line in b, c illustrates the position of the flow centreline

For the case of the sPTT model (\(\varepsilon =0.25\) and \(\beta =0.1\)) the velocity and the resulting strain-rate profiles are normalised in a similar way as done in Sect. 4.1.4, to take into account the shear-thinning of the velocity profile as \(\text {Wi}\) increases. It can be seen that despite the shear-thinning behaviour, the design works well up to \(\text {Wi}=0.2\), with a slight overprediction of \(\sim 5\%\) in the core of the optimised region. A fairly homogeneous strain-rate region is obtained when the Weissenberg number is further increased at \(\text {Wi}=0.4\), where a maximum deviation of \(\sim 10\%\) occurs. Larger velocity deviations occur almost in the majority of the optimised region when \(\text {Wi}\ge 0.4\), with a velocity overshoot being formed at the transition region located at the end of the optimised zone. This response results in an undesired strain-rate profile along the flow centreline, which overpredicts the target by \(\sim 20\%\) at \(\text {Wi}=1.0\). The inset figure in Fig. 14b considers the standard normalisation used for all the cases that consider constant viscosity fluids, where the influence of the shear-thinning on the velocity profile is clear. To quantify the influence of the shear-thinning without viscoelasticity, the flow of the inelastic PL fluid is considered, similarly to what was done for the TJ. The different behaviour of the \(\text {sPTT}\) and the PL fluids are given in more detail in Supplementary Material.

The results presented above for both non-Newtonian fluid models demonstrate that care needs to be taken when \(\text {Wi}>0.4\). Clearly, above these values, the behaviour of the strain-rate deviates significantly when compared to the Newtonian case and thus, the flow field may no longer be symmetric. As it is reported in Oliveira et al. (2009), an elastic instability is expected to occur above a critical Weissenberg number for the FF design, as the lateral stream impinges on the main stream. Furthermore, in Oliveira et al. (2011), it is shown experimentally that the flow of a Boger fluid within a common flow-focusing design of a square cross section becomes asymmetric at \(\text {Wi}=1.4\). In line with the TJ case, the critical limits of the onset of an elastic instability for the optimised FF design are expected to increase within the optimised geometry, given the wider area in the intersecting channels region.

4.2.5 Optimisation length effects

In this section, the effects of the optimisation lengths are investigated. All previous cases considered an optimisation length \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), while a transition length \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) was applied both at the beginning and the end of the target profile (see Fig. 2). Here, the length of the transition region remains the same and two cases with different lengths for homogeneous extension are optimised. The desired length for which each configuration is able to produce a constant strain-rate region is increased, considering the cases with \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(L_\text {opt}=7w_{1}\). As it was done for the case of \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\), Eqs. (3) and (4) are employed for defining the target profile for the 3D designs with \(\text {AR}=1\), while optimisations are done for \(\text {VR}=20\) and creeping flow conditions.

Figure 15a compares the normalised velocity and strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline of the optimised geometries, while in Fig. 15b, c, the optimised shapes for the cases with \(L_\text {opt}=4w_{1}\) and \(L_\text {opt}=7w_{1}\) are shown, respectively. Examining the target velocity profiles, it can be seen that as the length of the desired constant strain-rate region increases, the slope of the target profile decreases. This corresponds to a smaller nominal strain-rate that is expected to be applied on a fluid element that travels along the flow centreline. The employed transition regions are directly affected by this change in the slope, in terms of normalised velocity values that need to be obtained, which are in turn lower for increasing lengths. As a result, the optimiser will “push” the boundaries of the FF designs further away from the centreline, generating wider areas in the region of interest to achieve smaller velocities.

Strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline of the 3D optimised flow-focusing geometry (\(\text {AR}=1\), \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\)) for different velocity ratios, obtained a numerically and b experimentally. The inset figure of b demonstrates a 2D view of the fabricated microchannel with the optimised boundary superimposed for comparison

For all the optimisation cycles, the meshes M0 for each case are employed (Table 5). As previously, the dependence of the obtained solution to the numerical mesh is investigated by employing a more refine mesh M1 (details given in Table 5), where for both cases, a very good agreement is found with the maximum deviation at the evaluated strain-rates being less than 1%.

4.2.6 Numerical and experimental performance of the 3D optimised FF for different VR

Changing the flow rates in the different branches can be considered equivalent to imposing different contraction ratios and thus, one can force the fluid and/or the sample of interest to exhibit different Hencky strains (Oliveira et al. 2009, 2011, 2012b). As such, an experimentalist would ideally prefer to exploit this characteristic and make use of the same optimised configuration for various \(\text {VR}\). Here, we demonstrate both the numerical and the experimental performance of the 3D FF microchannel when different velocity ratios are considered. We focus on the performance of the design for varying velocity ratios within the range of \(1\le \text {VR}\le 100\). For the numerical study, all velocity ratios are examined under creeping flow conditions, while for the experiments, the equivalent study corresponds to a range of Reynolds numbers from \(0.01\lesssim \text {Re}\lesssim 5\) (as real inertialess flow is not possible).

Figure 16 demonstrates the strain-rate profiles along the flow centreline for both the numerical and the experimental examined cases. Starting from the numerical results shown in Fig. 16a, it can be seen that the optimised geometry works well for all the cases where \(\text {VR}\ge 10\) (maximum deviation is \(\le 3.5\%\) for all), generating a region of homogeneous extension. For lower velocity ratios (\(\text {VR}=1\)), the design fails to produce the desired behaviour, producing a maximum deviation of \(\sim 48\%\).

Contour plots of the normalised velocity magnitude with superimposed streamlines along the flow centreplane, comparing CFD and experimental results for the 3D optimised flow-focusing design with \(\text {AR}=1\), \(L_\text {opt}=3w_{1}\) and \(l_{\varepsilon }=0.5w_{1}\) when a \(\text {VR}=1\), b \(\text {VR}=10\), c \(\text {VR}=40\), and d \(\text {VR}=100\)

The velocity ratio can be expressed as a function of the horizontal average inlet velocity \(U_{1}\) as \(U_{\text {out}}=(2+\text {VR}^{-1})U_{1}\). As \(\text {VR}\) increases for \(VR>>1\), the centreline velocity at the outlet channel nearly plateaus, since the contribution of the vertical stream to the outlet flow rate becomes negligible and \(U_{\text {out}}\rightarrow 2U_{1}\), explaining this behaviour of the strain-rates. In Fig. 16b, it can be seen that the experimental results, although more noisy than the numerical results (as expected since \({\dot{\varepsilon }}\) is obtained by calculating the derivative of experimentally obtained data), when \(\text {VR}\ge 5\), a good performance is obtained, with the experiments resulting in strain-rate values that approximate well the desired behaviour. For lower velocity ratios and when \(\text {VR}\le 2\), the experiments show larger deviations from the target profile, due to the higher influence of the vertical stream, in agreement with the numerical simulations. Thus, although the design is optimised specifically for \(\text {VR}=20\), provided that \(U_{1} \gg U_{2}\), VR can be varied in a wide range and the final fully developed profiles will converge to the optimised profile.

Figure 17 presents a comparison between the CFD and the experimental velocity field in the region of interest for different velocity ratios, where the ability to resemble different contraction-type flows is depicted. More specifically for the cases of \(\text {VR}=1\), \(\text {VR}=10\), \(\text {VR}=40\), and \(\text {VR}=100\), the normalised contour plots of the velocity magnitude with superimposed streamlines along the flow centreplane are shown. The diverging streamlines seen for \(\text {VR}=1\) in Fig. 17a when the main stream enters the junction result in a decrease of the centreline velocity, which in turn results in the large deviations of strain-rate from the desired behaviour. On the contrary, for \(\text {VR}\ge 10\), the generated velocities are not affected significantly by the presence of the main stream, but are mostly influenced by the lateral streams (see Fig. 17b–d). Both the contour plots and the streamlines demonstrate the nice agreement between experiments and simulations. Small quantitative deviations in the velocity magnitude are due to errors intrinsic to the experimental methodology used, e.g. channel fabrication and the ability to perform measurements exactly at the location of the midplane.

5 Conclusions

The study of complex fluid systems under extensional flow conditions can provide a variety of important information, both in terms of the characterisation of viscoelastic fluids and the individual behaviour of particles, such as cells, fibres, proteins, and DNA, but often require flows with well defined and known characteristics, to allow or simplify their analysis. Two different arrangements have been investigated and optimised: a T-junction and a flow-focusing design. The multi-stream geometries optimised here give the ability to generate a region of homogeneous strain-rate and can be potential platforms for studies of cell and droplet deformation, or stretching of single molecules (e.g., DNA and proteins) under uniform controlled extensional flows. It is shown that the optimised configurations perform better than their standard counterparts, providing a wider region of homogeneous strain-rate. In addition, they have the potential to be used for performing measurements of the extensional properties of complex fluids. All designs have advantages and disadvantages and the choice of the geometry strongly depends on the application.

The good performance of the designs has been validated experimentally and the limits of their applications were tested using numerical simulations. The designs have been shown to work well in creeping flow and low Reynolds regimes, \(\text {Re}\le 10\). The configurations were also found suitable for studies that are related to viscoelastic fluids, but care should be taken if the fluids to be used exhibit high levels of elasticity and additionally if they have shear-dependent viscosity. Additionally, the ability of the 3D optimised FF geometry to operate efficiently when different velocity ratios are applied was tested. An agreement was found between experiments and numerics with the designs being able to generate the desired performance for the cases where \(\text {VR}\ge 5\), thus maintaining the major advantage offered by these configurations that is to be able to apply different Hencky strains on the fluid samples of interest.

Data Availability Statement

Data files containing the outlines of the optimised shapes presented in this paper are available for download at http://datacat.liverpool.ac.uk/id/eprint/961.

References

Abed WM, Domingues AF, Poole RJ, Dennis DJC (2017) Heat transfer enhancement in a cross-slot micro-geometry. Int J Therm Sci 121:249–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2017.07.017

Afonso A, Oliveira PJ, Pinho FT, Alves MA (2009) The log-conformation tensor approach in the finite-volume method framework. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 157:55–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2008.09.007

Afonso AM, Pinho FT, Alves MA (2010) Purely elastic instabilities in three-dimensional cross-slot geometries. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 165:743–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2010.03.010

Afonso AM, Oliveira PJ, Pinho FT, Alves MA (2011) Dynamics of high-Deborah-number entry flows: a numerical study. J Fluid Mech 677:272–304. https://doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2011.84

Alves MA (2008) Design a cross-slot flow channel for extensional viscosity measurements. AIP Conf Proc 1027:240–242

Alves MA, Pinho FT, Oliveira PJ (2001) Study of steady pipe and channel flows of a single-mode Phan-Thien-Tanner fluid. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 101:55–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0257(01)00159-8

Alves MA, Oliveira PJ, Pinho FT (2003) A convergent and universally bounded interpolation scheme for the treatment of advection. Int J Numer Meth Fluids 41:47–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/fld.428

Anna SL (2016) Droplets and bubbles in microfluidic devices. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 28:285–309. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-122414-034425

Arratia PE, Thomas CC, Diorio J, Gollub JP (2006) Elastic instabilities of polymer solutions in cross-channel Flow. Phys Rev Lett. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.144502

Arratia PE, Gollub JP, Durian DJ (2008) Polymeric filament thinning and breakup in microchannels. Phys Rev E. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.77.036309

Audet C, Dennis JE Jr (2006) Mesh adaptive direct search algorithms for constrained optimization. SIAM J Optim 17:188–217. https://doi.org/10.1137/040603371

Audet C, Le Digabel S, Tribes C (2009) NOMAD user guide. Tech. Rep. G-2009-37, Les cahiers du GERAD

Ballesta P, Alves MA (2017) Purely elastic instabilities in a microfluidic flow focusing device. Phys Rev Fluids. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.2.053301

Bird RB, Armstrong RC, Hassager O (1987) Dynamics of polymeric liquids. Fluid dynamics, vol 1. Wiley, New York

Burshtein N, Zografos K, Shen AQ, Poole RJ, Haward SJ (2017) Inertioelastic flow instability at a stagnation point. Phys Rev X 7:041039. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.7.041039

Chiarello E, Derzsi L, Pierno M, Mistura G, Piccin E (2015) Generation of oil droplets in a non-Newtonian liquid using a microfluidic T-junction. Micromachines 6:1825–1835. https://doi.org/10.3390/mi6121458

Christopher GF, Anna SL (2007) Microfluidic methods for generating continuous droplet streams. J Phys D Appl Phys 40:R319–R336. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/40/19/R01

Christopher GF, Anna SL (2009) Passive breakup of viscoelastic droplets and filament self-thinning at a microfluidic T-junction. J Rheol 53:663–683. https://doi.org/10.1122/1.3086871

Cruz FA, Poole RJ, Afonso AM, Pinho FT, Oliveira PJ, Alves MA (2016) Influence of channel aspect ratio on the onset of purely-elastic flow instabilities in three-dimensional planar cross-slots. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 227:65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2015.11.008

Cubaud T, Mason TG (2009) High-viscosity fluid threads in weakly diffusive microfluidic systems. New J Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/11/7/075029

Damiati S, Kompella UB, Damiati SA, Kodzius R (2018) Microfluidic devices for drug delivery systems and drug screening. Genes-Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9020103

du Roure O, Lindner A, Nazockdast EN, Shelley MJ (2019) Dynamics of flexible fibers in viscous flows and fluids. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 51:539–572. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-122316-045153

Dylla-Spears R, Townsend JE, Jen-Jacobson L, Sohn LL, Muller SJ (2010) Single-molecule sequence detection via microfluidic planar extensional flow at a stagnation point. Lab Chip 2010:1543–1549. https://doi.org/10.1039/b926847b

Fattal R, Kupferman R (2004) Constitutive laws for the matrix-logarithm of the conformation tensor. J Non-Newton Fluid Mech 123:281–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnnfm.2004.08.008

Galindo-Rosales FJ, Oliveira MSN, Alves MA (2013) Microdevices for extensional rheometry of low viscosity elastic liquids: a review. Microfluid Nanofluid 14:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10404-012-1028-1

Galindo-Rosales FJ, Oliveira MSN, Alves MA (2014) Optimized cross-slot microdevices for homogeneous extension. RSC Adv 4:7799–7804. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ra47230b

Gaudet S, McKinley GH (1998) Extensional deformation of non-Newtonian liquid bridges. Comput Mech 21:461–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004660050325

Gossett DR, Tse HT, Dudani JS, Goda K, Woods TA, Graves SW, Di Carlo D (2012a) Inertial manipulation and transfer of microparticles across laminar fluid streams. Small. https://doi.org/10.1002/smll.201200588

Gossett DR, Tse HTK, Lee SA, Ying Y, Lindgren AG, Yang OO, Rao J, Clark AT, Carlo DD (2012b) Hydrodynamic stretching of single cells for large population mechanical phenotyping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:7630–7635. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1200107109

Haringa C, de Jong C, Hoang DA, Portela LM, Kleijn CR, Kreutzer MT, van Steijn V (2019) Breakup of elongated droplets in microfluidic T-junctions. Phys Rev Fluids. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevFluids.4.024203

Haward SJ (2016) Microfluidic extensional rheometry using stagnation point flow. Biomicrofluidics. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4945604

Haward SJ, McKinley GH (2013) Instabilities in stagnation point flows of polymer solutions. Phys Fluids 25:083104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4818151

Haward SJ, Ober TJ, Oliveira MSN, Alves MA, McKinley GH (2012a) Extensional rheology and elastic instabilities of a wormlike micellar solution in a microfluidic cross-slot device. Soft Matter 8:536–555. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1sm06494k

Haward SJ, Oliveira MSN, Alves MA, McKinley GH (2012b) Optimised cross-slot flow geometry for microfluidic extensional rheometry. Phys Rev Lett. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.109.128301

Juarez G, Arratia PE (2011) Extensional rheology of DNA suspensions in microfluidic devices. Soft Matter 7:9444–9452. https://doi.org/10.1039/c1sm05347g

Lamousin HJ, Waggenspack WN (1994) NURBS-based free-form deformations. IEEE Comput Gr 14:59–65

Le Digabel S (2011) Algorithm 909: NOMAD: nonlinear optimization with the MADS algorithm. ACM T Math Softw 37:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1145/1916461.1916468