Abstract

A salt-tolerant denitrifying bacterium F1 was isolated in this study, which has high nitrite (NO2−–N) and nitrate (NO3−–N) removal abilities. The salt tolerance capacity of strain F1 was further verified and the effects of initial pH, initial NaNO2 concentration and inoculation size on the denitrification capacity of strain F1 under saline conditions were evaluated. Strain F1 was identified as Pannonibacter phragmitetus and named Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1. This strain can tolerate NaCl concentrations up to 70 g/L, and its most efficient denitrification capacity was observed at NaCl concentrations of 0–10 g/L. Under non-saline condition, the removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 at pH of 10 and inoculation size of 5% were 100% and 83%, respectively, after cultivation for 5 days. Gas generation was observed during the cultivation, indicating that an efficient denitrification performance was achieved. When pH was 10 and the inoculation size was 5%, both the highest removal percentages of NO2−–N (99%) and NO3−–N (95%) by strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 were observed at NaCl concentration of 10 g/L. When the NaCl concentration was 10 g/L, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can adapt to a wide range of neutral and alkaline environments (pH of 7–10) and is highly tolerant of NaNO2 concentration (0.4–1.6 g/L). In conclusion, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 has a great potential to be applied in the treatment of saline wastewater containing high nitrogen concentrations, e.g. coastal aquaculture wastewater.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the advantages of a short production cycle, high yield and convenient management, coastal aquaculture has rapidly developed as a pillar industry in the coastal region of China (Liang et al. 2018). For semi-intensive and/or intensive mariculture, the feed utilization rates were only about 4.0–27.4% (Chen et al. 2016). Owing to lack of indispensable production management and pollution control, more than 60% of the nitrogen in feed for coastal aquaculture was discharged into the adjacent waters without sufficient treatment, resulting in severe eutrophication and deterioration of ecological quality in coastal watersheds (Chen et al. 2016; Kroupova et al. 2005). A high concentration of nitrate can lead to water eutrophication, and even impose a serious threat to human health (e.g., malformation, cancerization, and mutation, etc.) when it is transformed into nitrosamines (Bhatnagar and Sillanpaa 2011; Zhao et al. 2011). High concentrations of nitrite can cause the suffocation of aquatic animals (e.g., fish, shrimp, etc.) by oxidizing the Fe(II) in hemoglobin and generating methemoglobin which would restrain the combination and release of hemoglobin towards oxygen (Zhang et al. 2018). Therefore, the development of an applicable technology for in situ removal of nitrate nitrogen (NO3−–N) and nitrite nitrogen (NO2−–N) in wastewater originating from coastal aquaculture is of urgent needed.

Microbial denitrification has many advantages, e.g., high efficiency, low economical investment, easy operation, and no secondary pollution, etc., and is consequently widely used to treat nitrogen contaminated water. Nitrogen removal by microorganisms mainly uses bacteria (e.g. nitrifying bacteria, denitrifying bacteria, etc.) with nitration and denitrification capacities to achieve morphological transformation of various nitrogenous compounds in wastewater (Lv et al. 2017). Most of NO2−–N in wastewater is removed by the nitrification of nitrifying bacteria. However, due to the slow growth of nitrifying bacteria, and they must grow in aerobic conditions, a long time is needed for their cultivation (Spieck and Lipski 2011; Vekeman et al. 2013). Therefore, it is difficult for nitrifying bacteria to become dominant bacteria and play their role in practical applications. Additionally, although the nitrification of nitrifying bacteria can effectively remove NO2−–N from water, it cannot thoroughly solve the nitrogen pollution problem, as nitrate is the final product of microbial nitrification and the denitrification of NO3−–N is still needed. Denitrifying bacteria, however, can make up for the limitation of nitrifying bacteria. In anoxic and anaerobic conditions, the NO2−–N and NO3−–N in wastewater can be transformed by denitrifying bacteria into nitrogen (N2) and nitrous oxide (N2O), which are eventually released into the atmosphere, and greatly reduce the nitrogen concentration in water (Coban et al. 2015). Coastal aquaculture wastewater contains not only high concentrations of nitrogen, but also a large amount of soluble salts. In a high saline environment, the growth and metabolism of most bacteria are likely to be inhibited, and even lead to death. This is mainly due to the increase of osmotic pressure caused by high salinity, the destruction of bacterial cell membranes, the excessive loss of water in bacterial cells and the separation of protoplasm (Liu et al. 2009). High salinity leads to the limitation of denitrification capacity for general denitrifying bacteria (Tang et al. 2014). Therefore, to identify bacteria with both denitrification capacity and salt tolerant characteristic is of great practical significance.

Many studies have been conducted to remove nitrogen from wastewater by denitrifying bacteria. For example, a heterotrophic nitrification bacterium Klebsiella sp. TN-10 was isolated from tannery wastewater, and it exhibited excellent characteristics to remove both NO3−–N and NO2−–N, with the removal percentages of 95% and 100%, respectively (Li et al. 2019). A novel heterotrophic bacterium Acinetobacter sp. T1 was isolated from activated sludge of a pig farm wastewater treatment plant and exhibited efficient heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification capability to utilize ammonium (NH4+–N), NO3−–N or NO2−–N as the sole nitrogen source, and the removal rates of 12.08, 5.53 and 1.69 mg/L/h, were obtained for NH4+–N, NO3−–N, and NO2−–N, respectively (Chen et al. 2019). Although extensive research has been carried out for removing nitrogen by using denitrifying bacteria, there are, however, only a few studies adequately cover the research and/or application of salt-tolerant denitrifying bacteria with salt-tolerance characteristics and efficient denitrification performance. A novel halophilic bacterium Bacillus litoralis N31 was isolated from mariculture water, and its nitrification rate increased with increasing initial NH4+–N concentration (from 10 to 250 mg/L) at 30–40 g/L NaCl (Huang et al. 2017). However, the removal ability of the strain Bacillus litoralis N31 to NO2−–N and NO3−–N was not verified. In summary, salt-tolerant nitrite-type denitrifying bacteria are necessary to be isolated and screened to treat coastal aquaculture wastewater with high nitrite concentration.

Therefore, in order to fill this technology gap, this study aims to: (1) identify the strain F1 that was obtained from seawall muddy water; (2) evaluate the denitrification capacity and salt tolerance of strain F1; and (3) quantify the effects of initial pH, initial NaNO2 concentration and inoculation size on the denitrification capacity of strain F1 under saline conditions. This study can provide an alternative and effective microbial resource for nitrogen removal in saline wastewater. Furthermore, this study may also promote the development of bioremediation technology for water quality control in coastal aquaculture systems.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain and media

Strain F1 was isolated and screened from the seawall muddy water samples in Dalian City, Liaoning Province (39° 38′ 31′′ N, 122° 58′ 19′′ E), and stored in the Key Laboratory of Wetland Ecology and Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China.

The culture media was described as follows: (1) ingredients for the denitrification medium (pH = 10) were: CH3COONa 5 g, K2HPO4 1 g, NaNO2 0.8 g (The initial nitrogen concentration was approximate 160 mg/L, including 115.9 ± 4.63 mg/L of NO2−–N and 42.47 ± 1.19 mg/L of NO3−–N, respectively. The NO3−–N was generated by oxidation of NO2−–N during medium preparation), CaCl2 0.03 g, NaCO3 1 g, FeSO4·7H2O 0.06 g, MgSO4·7H2O 0.2 g, deionized water 1000 mL. It is worth noting that FeSO4·7H2O was added after the addition of deionized water to avoid oxidation of divalent iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+) (Wu et al. 2019); (2) ingredients for the screen solid plate medium (pH = 10) were the same as the denitrification medium but with 2% agar (m/v) added. All media were autoclaved at 121 °C for 30 min before being used.

Identification of strain F1

Colony morphology and physiological and biochemical experiments

According to Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology (Goodfellow et al. 2012), the colony morphology and the physiological and biochemical characteristics of strain F1 were studied.

16S rDNA sequencing

The total DNA of strain F1 genome was extracted by a conventional method using an Ezup column bacterial genomic DNA extraction kit (Sangon, China). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of strain F1 genomic DNA was performed using total DNA as a template. The PCR reaction primer was a 16S rDNA amplification universal primer, in which the forward primer was 27F 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and the reverse primer was 1492R 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′. The PCR reaction process was carried out in a 25 μL system. The composition of the reaction system was described as follows: DNA template 0.5 μL, dNTP (mix) 1 μL, 10× Buffer (with Mg2+) 2.5 μL, Taq enzyme 0.2 μL, primer F (10 μM) 0.5 μL, primer R (10 μM) 0.5 μL, and double distilled water to 25 μL. PCR amplification was completed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 4 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 60 s, and a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min, and termination at 4 °C. A total of 5 μL of the PCR amplification product was taken and detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. After verification, the strip was cut and the PCR product was purified using a SanPrep column DNA Jgel recovery kit (Sangon, China). The recovered PCR products were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) company limited in China for 16S rDNA sequencing.

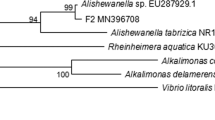

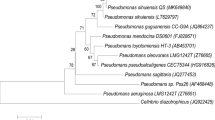

Phylogenetic analysis

The partial sequences obtained by 16S rDNA sequencing were searched against GenBank using the Advanced BLAST similarity search option accessible from the homepage at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The phylogenetic analysis was performed by using Mega 4.0 version (Arizona State University, 2007) software to search for related sequences with high homology. Multiple sequence alignment analysis was performed with program Clustal X. The evolutionary status of the phylogenetic tree of the bacteria in similar strains was analyzed by Neighbor-Joining (N-J) algorithm. The stability of the phylogenetic tree was analyzed by Boot-strap and evaluated based on 1000 replicates.

Experiments on salt-tolerance and nitrogen removal characteristics of strain F1

Denitrification capacity test

The culture solution of strain F1 with 5% inoculation size (v/v) was placed in 250 mL conical flask that contained 200 mL of sterilized denitrification medium to create an anoxic environment, and was cultivated in a constant temperature incubator at 30 °C for 5 days. The concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N in the denitrification medium were determined daily and the denitrification performance of strain F1 was evaluated. Three independent parallel experiments were designed for each treatment.

Salt tolerance test

The growth of strain F1 was observed by changing the salinity levels of the screen solid plate medium. The salinity levels were set at 0, 30, 50, 70, and 100 g/L NaCl concentrations, respectively. Strain F1 was streaked into the medium with each respective salinity treatment, and cultivated in a constant temperature incubator at 30 °C for 5 days. The bacterial colony growth was regarded as the basis for determining whether strain F1 tolerate the corresponding salinity levels. Three independent parallel experiments were designed for each treatment.

Effect of salinity levels on denitrification capacity of strain F1

The salinity levels of denitrification medium were set at 0, 10, 30, 50, 70, and 100 g/L NaCl concentrations, respectively. Strain F1 was transferred to each respective sterilized saline denitrification medium at a 5% inoculation size (v/v), and the mouth of the conical flask was sealed and statically cultured at 30 °C for 5 days. The concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N in the culture medium were determined before and after the 5 days cultivation and the denitrification performance of strain F1 was evaluated. Three independent parallel experiments were designed for each treatment.

Effect of initial pH value, initial NaNO2 concentration, and inoculation size on denitrification capacity of strain F1 in saline condition

A 200 mL sterilized denitrification medium containing 10 g/L NaCl concentration was packed in a 250 mL conical flask and strain F1 was cultivated in a sealed static chamber at 30 °C for 5 days. The NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal abilities of strain F1 were tested as affected by initial pH value, initial NaNO2 concentration, and inoculation size, respectively. (1) The initial pH values were set at 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, and 11, respectively; (2) the initial NaNO2 concentrations were set at 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 2.4, and 3.2 g/L (NaNO2 was added into the denitrifying medium without any initial NaNO2), respectively; and (3) the inoculation sizes (v/v) were set at 1, 3, 5, 7, and 10%, respectively. After a 5 days static cultivation, the concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N in the medium were determined. In this experiment, only each respective factor tested was changed while the other conditions remained constant. Three independent parallel experiments were designed for each treatment.

Sample analysis

The culture solution was centrifuged at 5000 r/min for 10 min, and the bacteria were separated. The supernatant was then diluted for measurement. The concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N in water samples were determined by N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine spectrophotometry and naphthylethylenediamine hydrochloride spectrophotometry, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of all the data was performed by using Microsoft Office Excel 2007 software and SPSS Statistics 22.0. All graphs were prepared by using Origin 9.1 (USA) software. The data in all figures was expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The means between different treatments were compared by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test at a significance level of 0.05.

The Genbank registration number of strain F1 was MN396535.

Results

Identification of strain F1

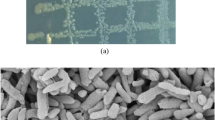

Microbial morphology and the physiological and biochemical characteristics of strain F1

Strain F1 was cultivated in the screen solid plate medium, and the colonies grown were round, small, neat edges, smooth surface and luster. Under the optical microscope, the bacteria morphology of strain F1 was observed to be rod-shaped and confirmed to belong to gram-negative bacteria by gram staining. The physiological and biochemical characteristics of strain F1 are shown in Table 1.

16S rDNA gene sequence and phylogenetic analysis

Strain F1 was identified by a series of DNA extraction, PCR amplification and agarose gel electrophoresis. The full length of the16S rDNA gene of strain F1 was 1440 bp (Fig. 1). A phylogenetic tree constructed by MEGA 4.0 showed that strain F1 was closest to the phylogenetic status of Pannonibacter phragmitetus (Fig. 2). The strain F1 was closest to the phylogenetic status of Pannonibacter phragmitetus. The 16S rDNA identification reveals that strain F1 is 99.72% homology genetic relationship with Pannonibacter phragmitetus (Genbank registration number: AJ314749.1). Therefore, according to morphological observation, the physiological and biochemical characteristics of strains, and 16S rDNA gene analysis, strain F1 was identified as Pannonibacter phragmitetus and named Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1. It was preserved at CGMCC on March 25, 2019, numbered CGMCC No: 17432.

Denitrification capacity of strain F1

NaNO2 was used as the sole source of nitrogen in this experiment. A small amount of NaNO2 however was still oxidized and rapidly converted into NaNO3, as reported by (Philips et al. 2002). Therefore, the initial nitrogen source of the denitrification medium included 115.9 ± 4.63 mg/L of NO2−–N and 42.47 ± 1.19 mg/L of NO3−–N, respectively. As shown in Fig. 3, the concentration of NO2−–N in the denitrification medium maintained stable in the prime 24 h statically cultivation, thereafter, the concentration of NO2−–N decreased with increasing cultivation time. For NO3−–N, however, the concentration remained stable until 36 h after cultivation, and the concentration of NO3−–N then decreased with increasing cultivation time. In general, the decrease of NO2−–N concentration was faster than NO3−–N, as a bigger slope was observed for NO2−–N than NO3−–N. After cultivation of 96 h, both removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 were greater than 95%, i.e., the concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N decreased from 115.90 ± 4.63 mg/L to 2.50 ± 0.33 mg/L, and from 42.47 ± 1.19 mg/L to 1.93 ± 0.21 mg/L, with the corresponding removal percentages of 98% and 95%, respectively. While, with the further increasing of cultivation time (i.e., 120 h), both concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N remained relatively stable. It is noteworthy that during the course of cultivation, the decrease of NO2−–N and NO3−–N concentrations was accompanied by gas formation, indicating that NO2−–N and NO3−–N in the denitrification medium were transformed into gases by strain F1. For the control treatment without inoculating strain F1, the concentrations of NO2−–N and NO3−–N did not evidently change during the cultivation process (only 4% nitrite was transformed to nitrate).

Removal of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 in denitrification medium with different NaCl concentrations. Values represent the mean of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviations. Columns containing different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 by Tukey’s test

Salt tolerance of strain F1

Strain F1 was screened from seawall muddy water, which was considered a saline environment. Therefore, we speculate that strain F1 is salt tolerant, to some degree. To verify this speculation, strain F1 was cultivated in screen solid plate medium with different salinity treatments for 5 days. The growth of strain F1 under different salinity treatments with increasing cultivation time is shown in Table 2. There were no colonies observed in medium with any salinity treatments after cultivation for 1 day. After cultivation for 2 days, the colonies started to grow obviously in medium with 0 and 30 g/L NaCl concentrations, and trace colonies was observed to grow in 50 g/L NaCl concentrations as well, but there were no colonies grew in medium with 70 and 100 g/L NaCl concentrations. After cultivation for 3 days, obvious colonies appeared in the medium with 0, 30, and 50 g/L NaCl concentrations, and trace colonies grew in the medium with 70 g/L NaCl concentration. After cultivation for 5 days, colony growth was observed in the medium with 0, 30, 50, and 70 g/L NaCl concentrations. There was no colony growth observed in the medium with 100 g/L NaCl concentration throughout the experiment. The above observation indicates that strain F1 can tolerate a wide range of salinity levels with up to 70 g/L NaCl concentration, although 70 g/L NaCl treatment lead to a slower growth rate of strain F1 compared to lower salinity treatments. Extremely high salinity treatment, i.e., 100 g/L NaCl concentration in this study, however, stopped the growth of strain F1.

Effect of salinity on denitrification capacity of strain F1

The removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N of strain F1 under different salinity levels after a 5 days cultivation are presented in Fig. 4. Strain F1 maintained high removal percentages for NO2−–N (99–100%) and NO3−–N (91–95%) when the NaCl concentration was below 10 g/L. However, the removal ability of strain F1 to NO2−–N and NO3−–N was significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited when the NaCl concentration was increased to 30 g/L and above. In the medium with 30, 50, 70 and 100 g/L NaCl concentrations, strain F1 exhibited low removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N, with the NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal percentages of 10–36% and 10–15%, respectively. This observation indicates that the NaCl concentration of 30 g/L and above had a significant (p < 0.05) and negative impact on the denitrification capacity of strain F1 compared to 0 and 10 g/L NaCl treatments. There was no significant difference in the NO3−–N removal percentage among treatments with 30, 50, 70 and 100 g/L NaCl concentrations. However, the NO2−–N removal percentage by strain F1 in treatment of 100 g/L NaCl concentrations was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than in 30 and 50 g/L NaCl concentrations.

Removal of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 in denitrification medium with different NaCl concentrations. Values represent the mean of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviations. Columns containing different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 by Tukey’s test

Effects of various factors on the denitrification capacity of strain F1 in saline conditions

Initial pH

Figure 5 illustrates the removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 in saline conditions (10 g/L NaCl) under different initial pH after cultivation for 5 days. The pH is one of the main external factors that can both directly and indirectly affect the growth and metabolism of microorganisms. Therefore, it is particularly important to evaluate the effect of initial pH on the denitrification capacity of denitrifying bacteria, i.e., strain F1 in this study. As shown in Fig. 5, under acidic condition (i.e., pH of 3 and 5), NO3−–N was not removed by strain F1. While, strain F1 exhibited a low NO2−–N removal ability (removal percentage of 29%) at the pH = 3. When the pH was increased to 7–11, the mean removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 were above 99% and above 48%, respectively. There was no significant difference in NO2−–N removal percentages among treatments with pH of 7, 9, 10, and 11. For NO3−–N, the removal percentage of NO3−–N reached a maximum value (83%) when the pH was 10, and the removal percentage was significantly (p < 0.05) higher than pH of 11. The above observation demonstrates that strain F1 could adapt to a wide range of neutral and alkaline environments (i.e., pH of 7–11) under saline conditions (i.e., 10 g/L NaCl).

Effect of initial pH on denitrification capacity of strain F1 in saline condition (10 g/L NaCl). Values represent the mean of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviations. Columns containing different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 by Tukey’s test

Initial NaNO2 concentration

Figure 6 shows the removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 in saline condition (10 g/L NaCl) under different initial NaNO2 concentrations after cultivation for 5 days. The greatest removal percentages of NO2−–N (99%) and NO3−–N (100%) by strain F1 were observed when the initial NaNO2 concentration was 0.4 g/L. When the initial NaNO2 concentrations were 0.8–1.6 g/L, the removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 were maintained at approximately 99% and 83%, respectively. With the increasing initial NaNO2 concentration (i.e., 2.4 and 3.2 g/L), the removal percentages of both NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 significantly declined (p < 0.05). However, strain F1 still exhibited a promising NO2−–N removal capacity (removal percentage of 80%) when the NaNO2 concentration was 3.2 g/L. The removal percentages of NO3−–N by strain F1 in treatments of 2.4 and 3.2 g/L initial NaNO2 concentration (47% and 54%, respectively) were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than 0.4, 0.8, and 1.6 g/L NaNO2 treatments (100%, 83% and 83%, respectively). Although the removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 decreased with the increasing initial NaNO2 concentration, strain F1 still exhibited some capacity for NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal in high initial NaNO2 concentration treatments. In general, strain F1 can tolerate a high concentration of NaNO2 up to 3.2 g/L.

Effect of initial NaNO2 concentration on denitrification capacity of strain F1 in saline condition (10 g/L NaCl). Values represent the mean of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviations. Columns containing different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 by Tukey’s test

Inoculation size

The removal percentages of NO2−–N and NO3−–N by strain F1 in saline conditions (10 g/L NaCl) under different inoculation sizes after cultivation for 5 days are presented in Fig. 7. The NO2−–N removal percentage by strain F1 in denitrification medium was higher than 99% for all the tested inoculation sizes. However, the removal percentage of NO3−–N was significantly (p < 0.05) reduced by the inoculation size of 10% compared to other treatments. When the inoculation size was 1–7%, the removal percentages of NO3−–N by strain F1 in the denitrification medium were between 75 and 93%. However, the removal percentage of NO3−–N was only 28% when the inoculation size was increased to 10%. This observation indicates that extremely high inoculation size (i.e., 10% in this study) can reduce the denitrification capacity of strain F1.

Effect of inoculation size on denitrification capacity of strain F1 in saline condition (10 g/L NaCl). Values represent the mean of three replicates and error bars represent standard deviations. Columns containing different letters indicate significant differences among treatments at p < 0.05 by Tukey’s test

Discussion

Salt-tolerance and denitrification capacity of the strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 as compared to similar strains of Pannonibacter phragmitetus

A few similar strains of Pannonibacter phragmitetus were isolated and most of the related studies were conducted regarding their ability to reduce Cr(VI) in soil with high Cr(VI) concentrations, to detoxify polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons under extreme conditions and their drug resistance to elucidate antibiotic resistance and infectivity mechanisms etc. (Zhou et al. 2017; Chai et al. 2019). To the best of our knowledge, only one study was conducted to evaluate the denitrification capacity of similar strains of Pannonibacter phragmitetus. A heterotrophic denitrifying bacterium Pannonibacter phragmitetus B1 was isolated from aquaculture water, which had denitrifying genes nirK, norB and narG (Bai et al. 2019). Strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus B1 was proved to have a good denitrification capacity, with the denitrification percentages of 99%, 100% and 99%, for NH4Cl, NaNO2 and NaNO3, respectively, when using NH4Cl, NaNO2, and NaNO3 as sole nitrogen source and the initial concentration of each respective nitrogen species was 14 mg/L (Bai et al. 2019). The salt-tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus B1, however, was not investigated, which hindered its application in saline conditions.

In this study, the salt tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 was verified after confirming its denitrification capacity, which fills both the knowledge and technical gaps of application in saline conditions. Strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 was proved to be an efficient salt-tolerant strain, which can tolerate NaCl concentrations of up to 70 g/L. When the NaCl concentration was below 10 g/L, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 exhibited promising NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal efficiencies, with the removal percentages as high as that in non-saline conditions. Additionally, although strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 showed a slower growth rate in saline conditions of 30–70 g/L NaCl concentrations, it still exhibited denitrification ability (i.e., the NO2−–N removal percentages of 23–36%). Salinity levels of coastal aquaculture wastewater vary with the location of aquaculture ponds (e.g., intertidal zone and supratidal zone, etc.) and aquaculture species (e.g., brackish water, brackish water and broad-salt species, etc.) (Primavera 2006). The salinity levels of coastal aquaculture wastewater reportedly ranged from 2 to 35 g/L NaCl concentrations (McIntosh and Fitzsimmons 2003; Tho et al. 2014; Li et al. 2018). The salt-tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 in this study was within the range of coastal aquaculture water. The high salt-tolerance and promising denitrification capacity of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 observed in this study provide a great potential for practical application in coastal aquaculture wastewater treatment. It is noteworthy that the salt tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 is currently domesticated in our laboratory for further improving its denitrification performance in higher salinity conditions, thereby extending its range of application.

Tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 to nitrite

As far as we know, most denitrifying bacteria were screened using nitrate as sole nitrogen source, e.g., Paracoccus marcusii (Cha et al. 2015), Acinetobacter sp. (Huang et al. 2013) and Pseudomonas stutzeri (Deng et al. 2014), etc. There are only a few studies in which nitrite was used as sole nitrogen source for denitrifying bacteria. For example, an aerobic heterotrophic denitrifying bacterium Pseudomonas sp. YY7 was screened by using nitrite as sole nitrogen source, and its denitrification rate was 18.20 mg NO2−–N L−1day−1, and the removal percentage of NO2−–N was over 80% at initial NO2−–N concentrations of 10–40 mg/L (Wan et al. 2011). A hypothermia highly efficient nitrite denitrifying bacterium Pseudomonas putida Y-12 was isolated and screened using nitrite as sole nitrogen source in a low temperature condition, and the removal percentages of NO2−–N and total nitrogen (TN) by strain Pseudomonas putida Y-12 at 15 °C were 99% and 52%, respectively (He and Li 2015). In this study, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 was isolated and screened from seawall muddy water with NaNO2 as sole nitrogen source. Strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can tolerate high concentrations of NaNO2, and showed efficient NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal abilities when the initial NaNO2 concentrations were 0.4–1.6 g/L. The NO2−–N concentration treated by strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 in this study was higher than the NO2−–N concentrations treated by strain Pseudomonas sp. YY7 (10–40 mg/L) and strain Pseudomonas putida Y-12 (15.22 mg/L). It was illustrated that strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 present a greater potential in denitrification treatment of wastewater with high nitrite concentration.

The tolerance of various denitrifying bacteria to NaNO2 concentration is different. If the NaNO2 concentration is too low, the supply of nitrogen source required for normal growth of bacteria will be insufficient, affecting their biological activity (Egli and Zinn 2003). However, excessive concentration of NaNO2 (50 mg/L) causes serious harm to the growth and normal metabolism of aquatic organisms (Kroupova et al. 2005). Therefore, low or high NaNO2 concentration may both affect the denitrification capacity of denitrifying bacteria. Strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can tolerate high concentrations of NaNO2 (0.4–1.6 g/L). Furthermore, although the denitrification capacity of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 was significantly reduced (p < 0.05) at the initial NO2−–N concentrations of 2.4 and 3.2 g/L treatments, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 still exhibited an acceptable denitrification capacity (Fig. 6) and there was no mass bacterial death observed. In summary, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can endure up to 3.2 g/L NaNO2, and grew in an acceptable manner and maintained an effective denitrification capacity.

Growth of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 in neutral and alkaline environments

Most denitrifying bacteria are suitable for growth in neutral and weak alkali environments (Zhang et al. 2012; Ye et al. 2016). The optimum pH of denitrification by most denitrifying bacteria was 7–8 (Tang et al. 2014; He, Li, and Xu 2015; Yang et al. 2013). However, when the pH was out of the optimal range, the denitrification capacity can be decreased. High pH will affect microbial growth and metabolism, leading to the reduction of its denitrification capacity (Zhang et al. 2015; He et al. 2015). The pH can affect the ionization degree of nutrients in the cultivation process, and the ability of bacteria to absorb nutrients is consequently affected, resulting in the weakening of activities of various enzymes in their growth and metabolism (Han et al. 2013). For example, high pH can inhibit the expression of nitrite reductase (NiRs), leading to nitrite accumulation in wastewater (Glass and Silverstein 1998). Strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 identified in this study can adapt to a wide range of neutral and alkaline environments, and has efficient NO2−–N and NO3−–N removal abilities when the initial pH was 7–11. In particular, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 showed the most effective denitrification capacity at the initial pH of 10. The pH of coastal aquaculture wastewater reportedly ranged from 7 to 10 (Li et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2017), demonstrating that strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can be potentially used for nitrogen removal in coastal aquaculture wastewater, especially for locations with high pH (e.g., pH of 10). Furthermore, the alkali-tolerance of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 also makes it possible to be applied in the treatment of drainage water originating from soda saline-alkaline farmlands, which are usually with high pH (Dendooven et al. 2010; Silva et al. 2008).

In this study, the denitrification capacity of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 in saline condition was evaluated considering the influence of pH, initial NaNO2 concentration and inoculation size. In saline conditions with 10 g/L NaCl concentration, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 can adapt to a wide range of neutral and alkaline environment and has a promising denitrification capacity. Additionally, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 was tolerant of high concentrations of NaNO2 and exhibited efficient nitrogen removal ability with NaNO2 concentrations up to 1.6 g/L. The inoculation size is also one of the important factors affecting the biological nitrogen removal of strains. An appropriate inoculation size is of great significance to obtain the highest denitrification capacity of strains. The role of denitrification can not be achieved if the inoculation size is not enough, while, too much inoculation size will cause the biological competition for nutrients and lead to the death of some bacteria (He et al. 2015). In this study, an optimal inoculation size of 3–7% was obtained for strain F1 in regarding to its denitrification capacity. However, other potential influencing factors like the temperature, carbon source and C/N ratio, etc., were not tested. Therefore, the denitrification capacity of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 is recommended to be further evaluated considering the above factors. Furthermore, strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 produced a large amount of bubbles in the culture in an anoxic condition as observed in this study. The gases produced in the denitrification process include N2, NO and N2O in theory (Coban et al. 2015), and it is recommended to quantify these gases in future studies for further revealing the nitrogen conversion mechanism in denitrification process. Furthermore, the practical use of strain Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1 for the treatment of real coastal aquaculture wastewater in field conditions is recommended for future study.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Bai H, Liao SA, Wang AL, Huang JH, Shu W, Ye JM (2019) High-efficiency inorganic nitrogen removal by newly isolated Pannonibacter phragmitetus B1. Bioresour Technol 271:91–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.09.090

Bhatnagar A, Sillanpaa M (2011) A review of emerging adsorbents for nitrate removal from water. Chem Eng J 168:493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2011.01.103

Cha IT, Song EJ, Seok Y, Lee H, Park I, Lee YK, Roh SW, Choi HJ, Nam YD, Seo MJ (2015) Draft genome sequence of a denitrifying bacterium Paracoccus marcusii PAMC 22219 isolated from Arctic marine sediment. Mar Genom 21:27–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2015.01.005

Chai LY, Ding CL, Li JW, Yang ZH, Shi Y (2019) Multi-omics response of Pannonibacter phragmitetus BB to hexavalent chromium. Environ Pollut 249:63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.005

Chen Y, Dong SL, Wang F, Gao QF, Tian XL (2016) Carbon dioxide and methane fluxes from feeding and no-feeding mariculture ponds. Environ Pollut 212:489–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.02.039

Chen SH, He SY, Wu CJ, Du DY (2019) Characteristics of heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification bacterium Acinetobacter sp. T1 and its application for pig farm wastewater treatment. J Biosci Bioeng 127:201–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.07.025

Coban O, Kuschk P, Kappelmeyer U, Spott O, Martienssen M, Jetten MSM, Knoeller K (2015) Nitrogen transforming community in a horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetland. Water Res 74:203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2015.02.018

Dendooven L, Alcantara-Hernandez Rocio J, Valenzuela-Encinas C, Luna-Guido M, Perez-Guevara F, Marsch R (2010) Dynamics of carbon and nitrogen in an extreme alkaline saline soil: a review. Soil Biol Biochem 42:865–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.02.014

Deng B, Fu LQ, Zhang XP, Zheng JJ, Peng LS, Sun JD, Zhu HY, Wang YB, Li WF, Wu XX, Wu D (2014) The denitrification characteristics of Pseudomonas stutzeri SC221-M and its application to water quality control in grass carp aquaculture. PLoS ONE 9:20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0114886

Egli T, Zinn M (2003) The concept of multiple-nutrient-limited growth of microorganisms and its application in biotechnological processes. Biotechnol Adv 22:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2003.08.006

Glass C, Silverstein J (1998) Denitrification kinetics of high nitrate concentration water: pH effect on inhibition and nitrite accumulation. Water Res 32:831–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0043-1354(97)00260-1

Goodfellow M, Kämpfer P, Busse HJ, Trujillo ME, Suzuki KI, Ludwig W, Whitman WB (2012) Bergeys, Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-68233-4

Han YH, Zhang WX, Zhuang ZG, Zhou ZH, Li M (2013) Isolation and characterization of the salt-tolerant aerobic denitrifying bacterial strain A-13. Acta Microbiol Sinica 53(1):47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.placenta.2013.09.009

He TX, Li ZL (2015) Isolation, screening and identification of the hypothermia highly efficient nitrite denitrifying bacteria. Acta Sci Circum 35:2393–2399. https://doi.org/10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2014.1013

He TX, Li ZL, Xu Y (2015) Denitrification characteristics of a hypothermia nitrite-denitrifier Pseudomonas putida Y-12. Acta Sci Circum 35:3071–3077

Huang XF, Li WG, Zhang DY, Qin W (2013) Ammonium removal by a novel oligotrophic Acinetobacter sp. Y16 capable of heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification at low temperature. Bioresour Technol 146:44–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2013.07.046

Huang F, Pan LQ, Lv N, Tang XM (2017) Characterization of novel Bacillus strain N31 from mariculture water capable of halophilic heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification. J Biosci Bioeng 124:564–571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.06.008

Kroupova H, Machova J, Svobodova Z (2005) Nitrite influence on fish: a review. Vet Med-czecn 50:461–471. https://doi.org/10.17221/5650-VETMED

Li ZP, Song WL, Liu F, Ding Y, You H, Liu HJ, Qi PS, Jin C (2018) The characteristic evolution of soluble microbial product and its effects on membrane fouling during the development of sponge membrane bioreactor coupled with fiber bundle anoxic bio-filter for treating saline wastewater. Bioresour Technol 266:51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2018.06.067

Li D, Liang XH, Jin Y, Wu CD, Zhou RQ (2019) Isolation and nitrogen removal characteristics of an aerobic heterotrophic nitrifying-denitrifying bacterium, Klebsiella sp. TN-10. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 188:540–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-018-02932-9

Liang YX, Cheng XW, Zhu H, Shutes B, Yan BX, Zhou QW, Yu XF (2018) Historical evolution of mariculture in China during past 40 years and its impacts on eco-environment. Chin Geogr Sci 28:363–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11769-018-0940-z

Liu CL, Yamamoto T, Nishiyama T, Fujii T, Furukawa K (2009) Effect of salt concentration in anammox treatment using non woven biomass carrier. J Biosci Bioeng 107:519–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiosc.2009.01.020

Lv PY, Luo JX, Zhuang XL, Zhang DQ, Huang ZB, Bai ZH (2017) Diversity of culturable aerobic denitrifying bacteria in the sediment, water and biofilms in Liangshui River of Beijing, China. Sci Rep 7:12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09556-9

McIntosh D, Fitzsimmons K (2003) Characterization of effluent from an inland, low-salinity shrimp farm: what contribution could this water make if used for irrigation. Aquacult Eng 27:147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0144-8609(02)00054-7

Philips S, Laanbroek HJ, Verstraete W (2002) Origin, causes and effects of increased nitrite concentrations in aquatic environments. Rev Environ Sci Bio 1:115–141. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020892826575

Primavera JH (2006) Overcoming the impacts of aquaculture on the coastal zone. Ocean Coast Manage 49:531–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2006.06.018

Silva CC, Guido ML, Ceballos JM, Marsch R, Dendooven L (2008) Production of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide in alkaline saline soil of Texcoco at different water contents amended with urea: a laboratory study. Soil Biol Biochem 40:1813–1822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.03.004

Spieck E, Lipski A (2011) Cultivation, growth physiology, and chemotaxonomy of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Method Enzymol 486:109–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381294-0.00005-5

Tang J, Xiao YN, Qu SS, Fu JX, Sun YQ, Wu R, Gao H (2014) Identification and denitrification characteristics of a strain of halophilic denitrifying bacteria. Chin J Environ Eng 8:5499–5506

Tho N, Merckx R, Ut VN (2014) Impacts of saline water irrigation and shrimp pond discharges on the surrounding waters of a coastal district in the Mekong delta of Vietnam. Environ Earth Sci 71:2015–2027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-013-2603-9

Vekeman B, Hoefman S, Vos PD, Spieck E, Heylen K (2013) A generally applicable cryopreservation method for nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol 36:579–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.syapm.2013.07.002

Wan CL, Yang X, Lee DJ, Du M, Wan F, Chen C (2011) Aerobic denitrification by novel isolated strain using, NO2 −–N mathcontainer loading mathjax, as nitrogen source. Bioresour Technol 102(15):7244–7248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.04.101

Wu SB, Vymazal J, Brix H (2019) Critical review: biogeochemical networking of iron in constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment. Environ Sci Technol 53(14):7930–7944. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b00958

Yang SH, Cho JK, Lee SY, Abanto OD, Kim SK, Ghosh C, Lim JS, Hwang SG (2013) Isolation and characterization of novel denitrifying bacterium Geobacillus sp. SG-01 strain from wood chips composted with swine manure. Asian Austral J Anim 26:1651–1658. https://doi.org/10.5713/ajas.2013.13184

Yang P, Lai DYF, Jin BS, Bastviken D, Tan LS, Tong C (2017) Dynamics of dissolved nutrients in the aquaculture shrimp ponds of the Min River estuary, China: concentrations, fluxes and environmental loads. Sci Total Environ 603:256–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.074

Ye J, Zhao B, An Q, Huang YS (2016) Nitrogen removal by Providencia rettgeri strain YL with heterotrophic nitrification and aerobic denitrification. Environ Technol 37:2206–2213. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593330.2016.1146338

Zhang QL, Liu Y, Ai GM, Miao LL, Zheng HY, Liu ZP (2012) The characteristics of a novel heterotrophic nitrification-aerobic denitrification bacterium, Bacillus methylotrophicus strain L7. Bioresour Technol 108:35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2011.12.139

Zhang SN, Wang XY, Xia DP (2015) Effects of initial pH on denitrification of microorganism. Environ Eng 33(S1):67–71

Zhang Y, Nie JT, Wei HY, Xu HT, Wang Q, Cong YQ, Tao JQ, Zhang Y, Chu LL, Zhou Y, Wu XY (2018) Electrochemical detection of nitrite ions using Ag/Cu/MWNT nanoclusters electrodeposited on a glassy carbon electrode. Sensor Actuat B-Chem 258:1107–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2017.12.001

Zhao YX, Feng CP, Wang QH, Yang YN, Zhang ZY, Sugiura N (2011) Nitrate removal from groundwater by cooperating heterotrophic with autotrophic denitrification in a biofilm-electrode reactor. J Hazard Mater 192:1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.06.008

Zhou YJ, Jiang T, Hu SH, Wang MX, Ming DS, Chen SC (2017) Genomic insights of Pannonibacter phragmitetus strain 31801 isolated from a patient with a liver abscess. Microbiologyopen 6:14. https://doi.org/10.1002/mbo3.515

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study is supported by Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment, Harbin Institute of Technology (No. ESK 201802), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2016YFC0500404-4), and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (No. 2017274).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XW carried out all experiments and drafted the manuscript. HZ (corresponding author) is responsible for this study, participated its design and help to draft the manuscript. BS, BF and BY provided technical and theoretical support. XY, HW and XC executed the experiments, analyzed all data and produced figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This article does not contain any studies with animals or human participants performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Zhu, H., Shutes, B. et al. Identification and denitrification characteristics of a salt-tolerant denitrifying bacterium Pannonibacter phragmitetus F1. AMB Expr 9, 193 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0918-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-019-0918-y