Abstract

Introduction

Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) is a rare, non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. The clinical spectrum of ECD is diverse, varying from asymptomatic focal lesion to life-threatening multisystem infiltration. Neurological manifestations of ECD are common, mostly due to the involvement of the central nerve system. However, spinal nerve or peripheral nerve involvement has rarely been mentioned.

Case presentation

Herein, we present a case of a 32-year-old female patient complaining about radiating pain on the front and lateral side of her left thigh for 2 months. Spinal MRI with contrast enhancement showed a space-occupying lesion on the left L3/L4 intervertebral foramen, indicating an initial diagnosis of lumbar nerve schwannoma. The patient underwent surgery to remove the mass and decompress the lumbar nerve. Postoperative histological examination revealed the diffuse infiltration of foamy histiocytes that were CD68+, CD163+, and CD1a− on immunostaining, which confirmed the diagnosis of Erdheim–Chester disease. The radiating pain was gradually alleviated and PET-CT was performed but showed no further involvement of ECD.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of ECD demonstrated as an infiltrative mass on the spinal nerve, with imaging manifestations and compression symptoms similar to those of peripheral nerve schwannoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) is a rare form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis of unknown etiology and is histologically characterized by the accumulation of foamy histiocytes that are CD68+, CD163+, and CD1a−. Clinically, ECD ranges from asymptomatic focal process to life-threatening multisystem involvement. Most frequently, ECD presents with infiltration of the long bones, but extraskeletal tissues, including those of the central nerve system (CNS), pituitary gland, cardiovascular system, lungs, retroperitoneum, kidneys, skin, and retro-orbital tissues, can also be involved [1]. Although the presence of CNS involvement is common in ECD patients, occurring in up to 50% of cases [2,3,4], spine involvement is rarely observed, with even fewer reports of spinal nerve lesion. In this article, we report an unusual case of a 32-year-old female patient with ECD mimicking lumbar spinal nerve schwannoma.

Case presentation

History and examination

A 32-year-old woman initially presented with radiating pain on the front and lateral side of her left thigh that started 2 months previously and kept worsening in the recent 2 weeks without numbness, weakness, or gait difficulty. Physical examination revealed L3/L4 interspinous and left perispinous mild tenderness as well as tenderness of the left sciatic nerve outlet. Femoral nerve stretch test of her left lower extremity was positive. She had full strength in both her upper and lower extremities with normal knee and ankle reflex, negative Babinski sign and negative Lasegue sign.

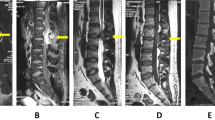

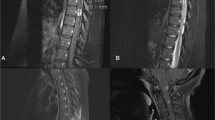

Plain radiography of the spine revealed no obvious abnormity. A contrast-enhanced spinal MRI showed a mass with T1WI hypointensity, T2WI hyperintensity and intense homogeneous gadolinium enhancement on the left L3/L4 intervertebral foramen (Fig. 1). The space-occupying lesion was estimated to be 25 × 15 × 13 mm in diameter, and the foramen was enlarged without infiltration of vertebrae, suggesting the diagnosis of schwannoma.

Operation and pathology

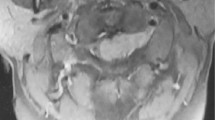

Surgery was performed to remove the mass and decompress the lumbar nerve. Part of the left articular process and transverse process was removed and then the left L3/L4 intervertebral foramen was well visualized. The lesion was fully exposed, estimated to be 25 × 15 × 13 mm in size and originated from the nerve. To achieve complete excision of the mass, part of the L3 lumbar nerve was removed together with the whole lesion. A biopsy was obtained from the mass, and macroscopically, the biopsy was irregular, 30 × 20 × 15 mm in diameter and had a grayish-yellow appearance. Histological examination of the biopsy revealed the diffuse infiltration of foamy histiocytes in a background of fibrosis associated with the infiltration of lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells and a minor population of Touton giant cells (Fig. 2). Upon immunostaining, the foamy histiocytes were positive for CD163 and CD68 and negative for CD1a and S-100. Therefore, the diagnosis of ECD was established.

Postoperative

The postoperative condition was stable. The radiating pain in her left lower extremity was gradually alleviated. Physical examination revealed hypoesthesia on her left lateral thigh due to partial excision of the L3 lumbar nerve. Considering the possibility of multisystem involvement in ECD, PET-CT was performed to detect any underlying lesion. The result, to our surprise, showed no increased FDG uptake in addition to the operative area, indicating no further involvement of ECD. The detection of BRAF V600E mutations was also performed and the result was negative. Therefore, this patient received no further treatment. Thus far, 4 months after the surgery, our patient has not reported further discomfort in our follow-up.

Discussion

ECD, which was first described by Jakob Erdheim and William Chester in 1930, is a rare form of non-Langerhans histiocytosis that is histologically characterized by the infiltration of foamy, lipid-laden, CD68+, and CD1a− histiocytes. ECD primarily affects patients between their ages of 40 and 70, and it has been reported to have a male predominance [2, 4, 5]. The underlying etiology of ECD has remained mostly a mystery since its first description. However, the recent identification of BRAF V600E mutations in ECD patients offers new insight into the pathogenesis of ECD [6]. The frequencies of the BRAF V600E mutation in ECD vary from 38 to 68% in most reports [2], with one report even claiming that BRAF V600E mutation can be detected in virtually all patients with ECD by ultrasensitive molecular biology techniques [7]. The discovery of BRAF V600E mutation not only reveals the clonal nature of ECD but also suggests a new approach to molecular-targeted therapy.

The clinical spectrum of ECD is wide and complicated, depending on the distribution and extent of the pathological tissue. Bone infiltration is the most universal symptom among ECD patients, found in over 90% of cases. Bone lesions, mainly affecting the appendicular skeleton and typically resulting in bilateral symmetric diaphyseal and metaphyseal osteosclerosis, can be detected on plain radiographs, CT, MRI as well as most sensitively on PET-CT [1, 2]. The extraskeletal involvement of ECD may include the CNS, pituitary gland, cardiovascular system, lungs, retroperitoneum, kidneys, skin, and retro-orbital tissues.

Neurologic signs or symptoms are common clinical manifestations of ECD, and they are mostly attributed to CNS involvement [1, 3, 8]. However, the involvement of the spine, spinal cord, and spinal nerves has rarely been reported in the literature. Invasion of the spine may involve vertebral bodies, thus causing compression fractures [9], or may involve the epidural and subdural space, thus causing soft tissue mass compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots [10,11,12,13]. The direct infiltration to spinal nerve roots or peripheral nerves is extremely rare, to our knowledge, with only one case report from Niu et al. mentioning the ECD involvement of cervical and lumbosacral nerve [14]. ECD mimicking schwannoma has been observed in the trigeminal nerve and the spine [10, 15]. In our case, the schwannoma-like ECD lesion was located at the L3 spinal nerve, resulting in direct infiltration and compression. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of ECD demonstrated as an infiltrative mass on a spinal nerve. The case we report, again, reminds spine surgeons and neurosurgeons about the possibility of ECD in the differential diagnosis of space-occupying lesion involving spinal nerve roots or peripheral nerves.

The diagnosis of ECD is based on the recognition of its distinctive histological features, supported by relevant clinical and radiologic manifestations. After establishing the diagnosis of ECD, comprehensive baseline evaluations, including radiographic and laboratory examinations, are needed to determine the burden of disease and detect the underlying abnormalities [2]. In addition, considering the possible therapeutic target of BRAF V600E mutations, accurate identification of the mutation is necessary [2]. However, in our case, PET-CT showed no involvement of other organs outside the surgery area, and the detection of the BRAF V600E mutation was also negative, which is rarely compared with the results of other case reports.

To date, no consensus has been achieved regarding the treatment of ECD due to the lack of RCTs and prospective studies. Among all the therapies that have been reported, including PEG-IFNα/IFN-α, Vemurafenib, Anakinra, Cladribine, Imatinib, Infliximab, corticosteroids and radiotherapy, only IFN-α has been identified as an independent predictor of survival [3]. In recent years, Vemurafenib, which targets BRAF V600E mutations, has been reported to achieve significant clinical outcomes [16, 17]. However, further research and evidence will be needed to develop a standard treatment for ECD.

Conclusion

The clinical spectrum of ECDErdheim–Chester is diverse, depending on the distribution of pathological tissue. We describe the first case of ECD demonstrated as an infiltrative mass on a spinal nerve, with imaging manifestations and compression symptoms similar to those of schwannoma. In regard to space-occupying lesion involving spinal nerve roots or peripheral nerves, the possibility of ECD should be considered.

References

Estrada-Veras JI, O’Brien KJ, Boyd LC, Dave RH, Durham BH, Xi LQ, et al. The clinical spectrum of Erdheim-Chester disease: an observational cohort study. Blood Adv. 2017;1:357–66.

Diamond EL, Dagna L, Hyman DM, Cavalli G, Janku F, Estrada-Veras J, et al. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and clinical management of Erdheim-Chester disease. Blood. 2014;124:483–92.

Arnaud L, Hervier B, Néel A, Hamidou MA, Kahn JE, Wechsler B, et al. CNS involvement and treatment with interferon-α are independent prognostic factors in Erdheim-Chester disease: a multicenter survival analysis of 53 patients. Blood. 2011;117:2778–82.

Cives M, Simone V, Rizzo FM, Dicuonzo F, Lacalamita MC, Ingravallo G, et al. Erdheim–Chester disease: a systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol/Hematol. 2015;95:1–11.

Haroche J, Arnaud L, Cohen-Aubart F, Hervier B, Charlotte F, Emile JF, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2013;39:299–311.

Ozkaya N, Rosenblum MK, Durham BH, Pichardo JD, Abdel-Wahab O, Hameed MR, et al. The histopathology of Erdheim–Chester disease: a comprehensive review of a molecularly characterized cohort. Mod Pathol. 2017;31:581–97.

Cangi MG, Biavasco R, Cavalli G, Grassini G, Dal-Cin E, Campochiaro C, et al. BRAF V600E -mutation is invariably present and associated to oncogene-induced senescence in Erdheim-Chester diseas. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:1596–602.

Parks NE, Goyal G, Go RS, Mandrekar J, Tobin WO. Neuroradiologic manifestations of Erdheim-Chester disease. Neurology 2018;8:15–20.

Caglar E, Aktas E, Aribas BK, Sahin B, Terzi A. Erdheim-Chester disease in thoracic spine: a rare case of compression fracture. Spine J. 2016;16:e257–e258.

Bunaux K, Sevestre H, Emile JF, Capel C, Chenin L, Peltier J. A case of Erdheim-Chester disease with spinal cord compression and sphenoid sinus involvement. Neurochirurgie. 2018;64:439–41.

Hwang BY, Liu A, Kern J, Goodwin CR, Wolinsky JP, Desai A. Epidural spinal involvement of Erdheim–Chester disease causing myelopathy. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1532–6.

Takeuchi T, Sato M, Sonomura T, Itakura T. Erdheim-Chester disease associated with intramedullary spinal cord lesion. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:62–4.

Tzoulis C, Gjerde IO, Softeland E, Neckelmann G, Strom E, Vintermyr OK, et al. Erdheim–Chester disease presenting with an intramedullary spinal cord lesion. J Neurol. 2012;259:2240–2.

Niu N, Cao XX, Cui R. A unique case of Erdheim-Chester disease with cervical and lumbosacral nerve involvement. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:881–3.

Alimohamadi M, Hartmann C, Paterno V, Samii M. Erdheim-Chester disease mimicking an intracranial trigeminal schwannoma: case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2015;15:493–8.

Haroche J, Cohenaubart F, Emile JF, Arnaud L, Maksud P, Charlotte F, et al. Dramatic efficacy of vemurafenib in both multisystemic and refractory Erdheim-Chester disease and Langerhans cell histiocytosis harboring the BRAF V600E mutation. Blood. 2013;121:1495–500.

Gjerde IO, Tzoulis C, Schwarzlmuller T, Softeland E, Biermann M, Neckelmann G, et al. Excellent response of intramedullary Erdheim-Chester disease to vemurafenib: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:171.

Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank our patient for allowing us to present this case.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Li, S., Hong, J. et al. Erdheim–Chester disease mimicking lumbar nerve schwannoma: case report and literature review. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 90 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0234-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0234-4