Abstract

Recently, there are tremendous developments on the number of controllable qubits in several quantum computing systems. For these implementations, it is crucial to determine the entanglement structure of the prepared multipartite quantum state as a basis for further information processing tasks. In reality, evaluation of a multipartite state is in general a very challenging task owing to the exponential increase of the Hilbert space with respect to the number of system components. In this work, we propose a systematic method using very few local measurements to detect multipartite entanglement structures based on the graph state—one of the most important classes of quantum states for quantum information processing. Thanks to the close connection between the Schmidt coefficient and quantum entropy in graph states, we develop a family of efficient witness operators to detect the entanglement between subsystems under any partitions and hence the entanglement intactness. We show that the number of local measurements equals to the chromatic number of the underlying graph, which is a constant number, independent of the number of qubits. In reality, the optimization problem involved in the witnesses can be challenging with large system size. For several widely used graph states, such as 1-D and 2-D cluster states and the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state, by taking advantage of the area law of entanglement entropy, we derive analytical solutions for the witnesses, which only employ two local measurements. Our method offers a standard tool for entanglement-structure detection to benchmark multipartite quantum systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entanglement is an essential resource for many quantum information tasks,1 such as quantum teleportation,2 quantum cryptography,3,4 nonlocality test,5 quantum computing,6 quantum simulation,7 and quantum metrology.8,9 Tremendous efforts have been devoted to the realization of multipartite entanglement in various systems,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 which provide the foundation for small- and medium-scale quantum information processing in near future and will eventually pave the way to universal quantum computing. In order to build up a quantum computing device, it is crucial to first witness multipartite entanglement. So far, genuine multipartite entanglement has been demonstrated and witnessed in experiment with a small amount of qubits in different realizations, such as 14-ion-trap-qubit,10 12-superconducting-qubit,14 and 12-photon-qubit systems.17

In practical quantum hardware, the unavoidable coupling to the environment undermines the fidelity between the prepared state and the target one. Taking the Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state for example, the state-of-the-art 10-superconducting-qubit13 and the 12-photon17 preparations only achieve the fidelity of 66.8% and 57.2%, respectively, which just exceed the threshold 50% for the certification of genuine entanglement. As the system size becomes larger, see for instance, Google’s a 72-qubit chip (https://www.sciencenews.org/article/google-moves-toward-quantum-supremacy-72-qubit-computer) and IonQ’s a 79-qubit system (https://physicsworld.com/a/ion-based-commercial-quantum-computer-is-a-first/), it is an experimental challenge to create genuine multipartite entanglement. Nonetheless, even without global genuine entanglement as the target state possesses, the experimental prepared state might still have fewer-body entanglement within a subsystem and/or among distinct subsystems.21,22,23 The study of lower-order entanglement, which can be characterized by the detailed entanglement structures,24,25,26 is important for quantum hardware development, because it might reveal the information on unwanted couplings to the environment and acts as a benchmark of the underlying system. Moreover, the certified lower-order entanglement among several subsystems could be still useful for some quantum information tasks.

Considering an N-partite quantum system and its partition into m subsystems (m ≤ N), the entanglement structure indicates how the subsystems are entangled with each other. Each subsystem corresponds to a subset of the whole quantum system. For instance, we can choose each subsystem to be each party (i.e., m = N), and then the entanglement structure indicates the entanglement between the N parties. In some specific systems, such as distributed quantum computing,27 quantum networks28 or atoms in a lattice, the geometric configuration can naturally determine the system partition (see Fig. 1 for an illustration). In other cases, one might not need to specify the partition in the beginning. By going through all possible partitions, one can investigate higher level entanglement structures, such as entanglement intactness (non-separability),23,26 which quantifies how many pieces in the N-partite state are separated.

A distributed quantum computing scenario. Three remote (small) quantum processors, owned by Alice, Bob, and Charlie, are connected by quantum links. Each of them possesses a few of qubits and performs quantum operations. In this case, the partition of the whole quantum system is determined by the locations of these processors. In order to perform global quantum operations involving multiple processors, entanglement among the processors are generally required. Thus, it is essential to benchmark the entanglement structure on this network

Multipartite entanglement-structure detection is generally a challenging task. Naively, one can perform state tomography on the system. As the system size increases, tomography becomes infeasible due to the exponential increase of the Hilbert space. Entanglement witness,29,30,31 on the other hand, provides an elegant solution to multipartite entanglement detection. In literature, various witness operators have been proposed to detect different types of quantum states, generally requiring a polynomial number of measurements with respect to the system size.32,33 Interestingly, a constant number of local measurement settings are shown to be sufficient to detect genuine entanglement for stabilizer states.34,35 Compared with genuine entanglement, multipartite entanglement structure still lacks a systematic exploration, due to the rich and complex structures of N-partite system. Recently, positive results have been achieved for detecting entanglement structures of GHZ-like states with two measurement settings26 and the entanglement of a specific 1-D cluster state of the 16-qubit superconducting quantum processor ibmqx5 machine from the IBM cloud.36 Unfortunately, it remains an open problem of efficient entanglement-structure detection of general multipartite quantum states.

In this work, we propose a systematic method to witness the entanglement structure based on graph states. Note that the graph state37,38 is one of the most important classes of multipartite states for quantum information processing, such as measurement-based quantum computing,39,40 quantum routing and quantum networks,28 quantum error correction,41 and Bell nonlocality test.42 It is also related to the symmetry-protected topological order in condensed matter physics.43 Typical graph states include cluster states, GHZ state, and the states involved in the encoding process of the 5-qubit Steane code and the concatenated [7,1,3]-CSS-code.38

The main idea of our entanglement-structure detection method runs as follows. First, with the close connection between the maximal Schmidt coefficient and quantum entropy, we upper-bound the fidelity of fully- and biseparable states. These bounds are directly related to the entanglement entropy of the underlying graph state with respect to certain bipartition. Then, inspired by the genuine entanglement detection method,34 we lower-bound the fidelity between the unknown prepared state and the target graph state, with local measurements corresponding to the stabilizer operators of the graph state. Finally, by comparing theses fidelity bounds, we can witness the entanglement structures, such as the (genuine multipartite) entanglement between any subsystem partitions, and hence the entanglement intactness.

Our detection method for entanglement structures based on graph states is presented in Theorems 1 and 2, which only involves k local measurements. Here, k is the chromatic number of the corresponding graph, typically, a small constant independent of the number of qubits. For several common graph states, 1-D and 2-D cluster states and the GHZ state, we construct witnesses with only k = 2 local measurement settings, and derive analytical solutions to the optimization problem. These results are shown in Corollaries 1–4. The proofs of propositions and theorems are left in Methods, and the proofs of Corollaries 1–4 are presented in Supplementary Methods 1–4.

Results

Definitions of multipartite entanglement structure

Let us start with the definitions of multipartite entanglement structure. Considering an N-qubit quantum system in a Hilbert space \({\cal{H}} = {\cal{H}}_{2}^{ \otimes N}\), one can partition the whole system into m nonempty disjoint subsystems Ai, i.e., \(\{ N\} \equiv \{ 1,2, \ldots ,N\} = \mathop {\bigcup}\nolimits_{i = 1}^{m} {A_i}\) with \({\cal{H}} = \mathop { \otimes }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{m} {\cal{H}}_{A_i}\). Denote this partition to be \({\cal{P}}_{m} = \{ A_{i}\}\) and omit the index m when it is clear from the context. Similar to definitions of regular separable states, here, we define fully- and biseparable states with respect to a specific partition \({\cal{P}}_{m}\) as follows.

Definition 1

An N-qubit pure state, \(\left| \mathrm{\Psi}_{f} \right\rangle \in \mathcal{H}\), is \(\mathcal{P}\)-fully separable, iff it can be written as

An N-qubit mixed state ρf is \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable, iff it can be decomposed into a convex mixture of \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable pure states

with pi ≥ 0, ∀i and \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {p_i} = 1\).

Denote the set of \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable states to be \(S_{f}^{\cal{P}}\). Thus, if one can confirm that a state \(\rho \ \notin \ S_{f}^{\cal{P}}\), the state ρ should possess entanglement between the subsystems {Ai}. Such kind of entanglement could be weak though, since it only requires at least two subsystems to be entangled. For instance, the state \(\left| {\mathrm{\Psi }} \right\rangle = \left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_{A_{1}A_{2}}} \right\rangle \otimes \mathop {\prod}\nolimits_{i = 3}^{m} {\left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_{A_{i}}} \right\rangle }\) is called entangled nevertheless only with entanglement between A1 and A2. It is interesting to study the states where all the subsystems are genuinely entangled with each other. Below, we define this genuine entangled state via \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable states.

Definition 2

An N-qubit pure state, \(\left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_s} \right\rangle \in \cal{H}\), is \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable, iff there exists a subsystem bipartition \(\{ A,\bar A\}\), where \(A = \mathop {\bigcup}\nolimits_i {A_i}\), \(\bar A = \{ N\} /A \ \ne \ \emptyset\), the state can be written as,

An N-qubit mixed state ρb is \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable, iff it can be decomposed into a convex mixture of \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable pure states,

with pi ≥ 0, ∀i and \(\mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {p_i} = 1\), and each state \(\left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_b^i} \right\rangle\) can have different bipartitions.

Denote the set of bi-separable states to be \(S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\). It is not hard to see that \(S_{f}^{\cal{P}} \subset S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\).

Definition 3

A state ρ possesses \(\cal{P}\)-genuine entanglement iff \(\rho \ \notin \ S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\).

The three entanglement-structure definitions of \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable, \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable, and \(\cal{P}\)-genuinely entangled states can be viewed as generalized versions of regular fully separable, bi-separable, and genuinely entangled states, respectively. In fact, when m = N, these pairs of definitions are the same.

Following the conventional definitions, a pure state |Ψm〉 is m-separable if there exists a partition \({\cal{P}}_m\), the state can be written in the form of Eq. (1). The m-separable state set, Sm, contains all the convex mixtures of the m-separable pure states, \(\rho _{m} = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i} {p_{i}} \left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_{m}^{i}} \right\rangle \left\langle {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_{m}^{i}} \right|\), where the partition for each term \(\left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_m^i} \right\rangle\) needs not to be same. It is not hard to see that Sm+1 ⊂ Sm. Meanwhile, define the entanglement intactness of a state ρ to be m, iff ρ ∉ Sm+1 and ρ ∈ Sm. Thus, as ρ ∉ Sm+1, the intactness is at most m, i.e., the non-separability can serve as an upper bound of the intactness. When the entanglement intactness is 1, the state is genuinely entangled; and when the intactness is N, the state is fully separable. See Fig. 2 for the relationships among these definitions.

Venn diagrams to illustrate relationships of several separable sets. a To illustrate the separability definitions based on a given partition, we consider a tripartition \({\cal{P}}_{3} = \{ A_{1},A_{2},A_{3}\}\) here. The \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state set \(S_{f}^{\cal{P}}\) is at the center, contained in three bi-separable sets with different bipartitions. The \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state set \(S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\) is the convex hull of these three sets. A state possesses \(\cal{P}\)-genuine entanglement if it is outside of \(S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\). Note that this becomes the case of three-qubit entanglement when each party Ai contains one qubit.22 b Separability hierarchy of N-qubit state with Sm+1 ⊂ Sm and 2 ≤ m ≤ N. The m-separable state set Sm is the convex hull of separable states with different m-partitions. Thus \(S_{f}^{{\cal{P}}_{m}} \subset S_{m}\), and one can investigate Sm by considering all \(S_{f}^{{\cal{P}}_{m}}\). A state possesses genuine multipartite entanglement (GME) if it is outside of S2, and is (fully) N-separable if it is in SN

By definitions, one can see that if a state is \({\cal{P}}_m\)-fully separable, it must be m-separable. Of course, an m-separable state might not be \({\cal{P}}_m\)-fully separable, for example, if the partition is not properly chosen. In experiment, it is important to identify the partition under which the system is fully separated. With the partition information, one can quickly identify the links where entanglement is broken. Moreover, for some systems, such as distributed quantum computing, multiple quantum processor, and quantum network, natural partition exists due to the system geometric configuration. Therefore, it is practically interesting to study entanglement structure under partitions.

Entanglement-structure detection method

Let us first recap the basics of graph states and the stabilizer formalism.37,38 In a graph, denoted by G = (V, E), there are a vertex set V = {N} and a edge set E ⊂ [V]2. Two vertexes i, j are called neighbors if there is an edge (i, j) connecting them. The set of neighbors of the vertex i is denoted as Ni. A graph state is defined on a graph G, where the vertexes represent the qubits initialized in the state of \(\left| + \right\rangle = (\left| 0 \right\rangle + \left| 1 \right\rangle )/\sqrt 2\) and the edges represent a Controlled-Z (C-Z) operation, \({\mathrm{CZ}}^{\{ i,j\} } = \left| 0 \right\rangle _i\left\langle 0 \right| \otimes {\mathbb{I}}_j + \left| 1 \right\rangle _i\left\langle 1 \right| \otimes Z_j\), between the two neighbor qubits. Then the graph state can be written as,

Denote the Pauli operators on qubit i to be Xi, Yi, Zi. An N-partite graph state can also be uniquely determined by N independent stabilizers,

which commute with each other and Si|G〉 = |G〉, ∀i. That is, the graph state is the unique eigenstate with eigenvalue of +1 for all the N stabilizers. Here, Si contains identity operators for all the qubits that do not appear in Eq. (6). As a result, a graph state can be written as a product of stabilizer projectors,

The fidelity between ρ and a graph state |G〉 can be obtained from measuring all possible products of stabilizers. However, as there are exponential terms in Eq. (7), this process is generally inefficient for large systems. Hereafter, we consider the connected graph, since its corresponding graph state is genuinely entangled.

Now, we propose a systematic method to detect entanglement structures based on graph states. First, we give fidelity bounds between separable states and graph states as the following proposition.

Proposition 1

Given a graph state |G〉 and a partition \({\cal{P}} = \{ A_{i}\}\), the fidelity between |G〉 and any \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state is upper bounded by

and the fidelity between |G〉 and any \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state is upper bounded by

where \(\{ A,\bar A\}\) is a bipartition of {Ai}, and S(ρA) = −Tr[ρA log2 ρA] is the von Neumann entropy of the reduced density matrix \(\rho _A = {\mathrm{Tr}}_{\bar A}(\left| G \right\rangle \left\langle G \right|)\).

The bound in Eq. (9) is tight, i.e., there always exists a \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state to saturate it. The bound in Eq. (8) may not be tight for some partition \(\cal{P} = \{ A_{\it{i}}\}\) and some graph state |G〉. In addition, we remark that to extend Theorem 1 from the graph state to a general state |Ψ〉, one should substitute the entropy in the bounds of Eqs. (8) and (9) with the min-entropy S∞(ρA) = −logλ1 with λ1 the largest eigenvalue of \(\rho _A = {\mathrm{Tr}}_{\bar A}(\left| \Psi \right\rangle \left\langle \Psi \right|)\).

Next, we propose an efficient method to lower-bound the fidelity between an unknown prepared state and the target graph state. A graph is k-colorable if one can divide the vertex set into k disjoint subsets \({\bigcup} {V_l} = V\) such that any two vertexes in the same subset are not connected. The smallest number k is called the chromatic number of the graph. (Note that the colorability is a property of the graph (not the state), one may reduce the number of measurement settings by local Clifford operations.38) We define the stabilizer projector of each subset Vl as

where Si is the stabilizer of |G〉 in subset Vl. The expectation value of each Pl can be obtained by one local measurement setting \(\mathop { \otimes }\nolimits_{i \in V_l} X_i\mathop { \otimes }\nolimits_{j \in V/V_l} Z_j\). Then, we can propose a fidelity evaluation scheme with k local measurement settings, as the following proposition.

Proposition 2

For a graph state \(\left| G \right\rangle \left\langle G \right|\) and the projectors Pl defined in Eq. ( 10 ), the following inequality holds,

where A ≥ B indicates that (A − B) is positive semidefinite.

Note that Proposition 2 with k = 2 case has also been studied in literature.34 Combining Propositions 1 and 2, we propose entanglement-structure witnesses with k local measurement settings, as presented in the following theorem.

Theorem 1

Given a partition \({\cal{P}} = \{ A_{i}\}\), the operator \(W_{f}^{\cal{P}}\) can witness non-\(\cal{P}\)-fully separability (entanglement),

with \(\langle W_{f}^{\cal{P}}\rangle \ge 0\) for all \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable states; and the operator \(W_{b}^{\cal{P}}\) can witness \(\cal{P}\)-genuine entanglement,

with \(\langle W_{b}^{\cal{P}}\rangle \ge 0\) for all \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable states, where \(\{ A,\bar A\}\) is a bipartition of {Ai}, \(\rho _{A} = {\mathrm{Tr}}_{\bar A}(\left| G \right\rangle \left\langle G \right|)\), and the projectors Pl is defined in Eq. (10).

The proposed entanglement-structure witnesses have several favorable features. First, given an underlying graph state, the implementation of the witnesses is the same for different partitions. This feature allows us to study different entanglement structures in one experiment. Note that the witness operators in Eqs. (12) and (13) can be divided into two parts: The measurement results of Pl obtained from the experiment rely on the prepared unknown state and are independent of the partition; The bounds, \(1 + \min {\mkern 1mu} (\max )_{\{ A,\bar A\} }2^{ - S(\rho _A)}\), on the other hand, rely on the partition and are independent of the experiment. Hence, in the data postprocessing of the measurement results of Pl, we can study various entanglement structures for different partitions by calculating the corresponding bounds analytically or numerically.

Second, besides investigating the entanglement structure among all the subsystems, one can also employ the same experimental setting to study that of a subset of the subsystems, by performing different data postprocessing. For example, suppose the graph G is partitioned into three parts, say A1, A2, and A3, and only the entanglement between subsystems A1 and A2 is of interest. One can construct new witness operators with projectors \(P_{l}^{\prime}\), by replacing all the Pauli operators on the qubits in A3 in Eq. (10) to identities. Such measurement results can be obtained by processing the measurement results of the original Pl. Then the entanglement between A1 and A2 can be detected via Theorem 1 with projectors \(P_{l}^{\prime}\) and the corresponding bounds of the graph state \(\left| {G_{A_{1}A_{2}}} \right\rangle\). Details are discussed in Supplementary Note 1.

Third, when each subsystem Ai contains only one qubit, that is, m = N, the witnesses in Theorem 1 become the conventional ones. It turns out that Eq. (13) is the same for all the graph states under the N-partition \({\cal{P}}_{N}\), as shown in the following corollary. Note that, a special case of the corollary, the genuine entanglement witness for the GHZ and 1-D cluster states, has been studied in literature.34

Corollary 1

The operator \(W_{b}^{{\cal{P}}_{N}}\) can witness genuine multipartite entanglement,

with \(\langle W_{b}^{{\cal{P}}_{N}}\rangle \ge 0\) for all bi-separable states, where Pl is defined in Eq. (10) for any graph state.

Fourth, the witness in Eq. (12) can be naturally extended to identify non-m-separability, by investigating all possible partitions \({\cal{P}}_{m}\) with fixed m. In fact, according to the definition of m-separable states and Eq. (8), the fidelity between any m-separable state ρm and the graph state |G〉 can be upper bounded by \({\mathrm{max}}_{{\cal{P}}_{m}}{\mathrm{min}}_{\{ A,\bar{A}\} }2^{ - S(\rho _{A})}\), where the maximization is over all possible partitions with m subsystems. As a result, we have the following theorem on the non-m-separability.

Theorem 2

The operator Wm can witness non-m-separability,

with 〈Wm〉 ≥ 0 for all m-separable states, where the maximization takes over all possible partitions \({\cal{P}}_{m}\) with m subsystems, the minimization takes over all bipartition of \({\cal{P}}_{m}\), \(\rho _A = {\mathrm{Tr}}_{\bar A}(\left| G \right\rangle \left\langle G \right|)\), and the projector Pl is defined in Eq. (10).

The robustness analysis of the witnesses proposed in Theorems 1 and 2 under the white noise is presented in Methods. It shows that our entanglement-structure witnesses are quite robust to noise. Moreover, the optimization problems in Theorems 1 and 2 are generally hard, since there are exponentially many different possible partitions. Surprisingly, for several widely used types of graph states, such as 1-D, 2-D cluster states, and the GHZ state, we find the analytical solutions to the optimization problem, as shown in the following section.

Applications to several typical graph states

In this section, we apply the general entanglement detection method proposed above to several typical graph states, 1-D, 2-D cluster states, and the GHZ state. Note that for these states the corresponding graphs are all 2-colorable. Thus, we can realize the witnesses with only two local measurement settings. For clearness, the vertexes in the subsets V1 and V2 are associated with red and blue colors respectively, as shown in Fig. 3. We write the stabilizer projectors defined in Eq. (10) for the two subsets as,

The more general case with k-chromatic graph states is presented in Supplementary Note 1.

We start with a 1-D cluster state |C1〉 with stabilizer projectors in the form of Eq. (16). Consider an example of tripartition \({\cal{P}}_{3} = \{ A_{1},A_{2},A_{3}\}\), as shown in Fig. 3a, there are three ways to divide the three subsystems into two sets, i.e., \(\{ A,\bar A\}\) = {A1, A2A3}, {A2, A1A3}, {A3, A1A2}. It is not hard to see that the corresponding entanglement entropies are \(S(\rho _{A_{1}}) = S(\rho _{A_{3}}) = 1\) and \(S(\rho _{A_{2}}) = 2\). Note that in the calculation, each broken edge will contribute 1 to the entropy, which is a manifest of the area law of entanglement entropy.44 According to Theorem 1, the operators to witness \({\cal{P}}_{3}\)-entanglement structure are given by,

where the two projectors P1 and P2 are defined in Eq. (16) with the graph of Fig. 3a.

Next, we take an example of 2-D cluster state |C2〉 defined in a 5 × 5 lattice and consider a tripartition, as shown in Fig. 3b. Similar to the 1-D cluster state case with the area law, the corresponding entanglement entropies are \(S(\rho _{A_{1}}) = S(\rho _{A_{3}}) = 5\) and \(S(\rho _{A_{2}}) = 4\). According to Theorem 1, the operators to witness \({\cal{P}}_{3}\)-entanglement structure are given by,

where the two projectors P1 and P2 are defined in Eq. (16) with the graph of Fig. 3b. Similar analysis works for other partitions and other graph states.

Now, we consider the case where each subsystem Ai contains exactly one qubit, \({\cal{P}}_{N}\). Then, witnesses in Eq. (12) become the conventional ones, as shown in the following Corollary.

Corollary 2

The operator \(W_{f,C}^{{\cal{P}}_{N}}\) can witness non-fully separability (entanglement),

with \(\langle W_{f,C}^{{\cal{P}}_{N}}\rangle \ge 0\) for all fully separable states, where the two projectors P1 and P2 are defined in Eq. (16) with the stabilizers of any 1-D or 2-D cluster state.

Here, we only show the cases of 1-D and 2-D cluster states. We conjecture that the witness holds for any (such as 3-D) cluster states. For a general graph state, on the other hand, the corollary does not hold. In fact, we have a counter example of the GHZ state shown in Fig. 3c. It is not hard to see that for any GHZ state, the entanglement entropy is given by,

Then, Eqs. (12) and (13) yield the same witnesses. That is, the witness constructed by Theorem 1 for the GHZ state can only tell genuine entanglement or not.

Following Theorem 2, one can fix the number of the subsystems m and investigate all possible partitions to detect the non-m-separability. The optimization problem can be solved analytically for the 1-D and 2-D cluster states, as shown in Corollary 3 and 4, respectively.

Corollary 3

The operator \(W_{m,C_{\mathrm{1}}}\) can witness non-m-separability,

with \(\langle W_{m,C_1}\rangle \ge 0\) for all m-separable states, where the two projectors P1 and P2 are defined in Eq. (16) with the stabilizers of a 1-D cluster state.

In particular, when m = 2 and m = N, \(W_{m,C_{\mathrm{1}}}\) becomes the entanglement witnesses in Eqs. (14) and (19), respectively.

Corollary 4

The operator \(W_{m,C_{\mathrm{2}}}\) can witness non-m-separability for N ≥ m(m − 1)/2,

with \(\langle W_{m,C_2}\rangle \ge 0\) for all m-separable states, where the two projectors P1 and P2 are defined in Eq. (16) with the stabilizers of a 2-D cluster state.

We remark that the witnesses constructed in Corollaries 1, 2, and 3 are tight. Take the witness \(W_{m,C_{\mathrm{1}}}\) in Corollary 3 as an example. There exists an m-separable state ρm that saturates \({\mathrm{Tr}}(\rho _mW_{m,C_1}) = 0\). In addition, as m ≤ 5, the witness \(W_{m,C_{\mathrm{2}}}\) in Corollary 4 is also tight. Detailed discussions are presented in Supplementary Methods 1–4.

Discussion

In this work, we propose a systematic method to construct efficient witnesses to detect entanglement structures based on graph states. Our method offers a standard tool for entanglement-structure detection and multipartite quantum system benchmarking. The entanglement-structure definitions and the associated witness method may further help to detect novel quantum phases, by investigating the entanglement properties of the ground states of related Hamiltonians.43

The witnesses proposed in this work can be directly generalized to stabilizer states,6,45 which are equivalent to graph states up to local Clifford operations.38 It is interesting to extend the method to more general multipartite quantum states, such as the hyper-graph state46 and the tensor network state.47 Meanwhile, the generalization to the neural network state48 is also intriguing, since this kind of ansatz is able to represent broader quantum states with a volume law of entanglement entropy,49 and is a fundamental block for potential artificial intelligence applications. In addition, one may utilize the proposed witness method to detect other multipartite entanglement properties, such as the entanglement depth and width,50,51 as m-separability in this work. Moreover, one can also consider the self-testing scenario, such as (measurement-) device-independent settings,52,53,54 which can help to manifest the entanglement structures with less assumptions on the devices. Furthermore, translating the proposed entanglement witnesses into a probabilistic scheme is also interesting.55,56

Methods

Proof of Proposition 1

Proof. First, let us prove the \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state case in Eq. (9). Since the \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state set \(S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\) is convex, one only needs to consider the fidelity |〈Ψb|G〉|2 of the pure state |Ψb〉 defined in Eq. (3). It is known that the maximal value of the fidelity equals to the largest Schmidt coefficient of |G〉 with regard to the bipartition \(\{ A,\bar {A}\}\),57 i.e.,

with the Schmidt decomposition \(\left| G \right\rangle = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_{i = 1}^d {\sqrt {\lambda _i} } \left| {{\mathrm{\Phi }}_i} \right\rangle _A\left| {{\mathrm{\Phi }}_i^\prime } \right\rangle _{\bar A}\) and λ1 ≥ λ2 ≥ ⋯ ≥ λd. For general graph state |G〉, the spectrum of any reduced density matrix ρA is flat, i.e., λ1 = λ2 = ⋯λd, with d being the rank of ρA.58 As a result, one has

To get an upper bound, one should maximize \(2^{ - S(\rho _{A})}\) on all possible subsystem bipartitions and then get Eq. (9).

Second, we prove the \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state case in Eq. (8). Similarly, we only need to upper-bound the fidelity of the pure state |Ψf〉 defined in Eq. (1), due to the convexity property of the \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state set \(S_{\mathrm{f}}^{\cal{P}}\). From the proof of Eq. (9) above, we know that the fidelity of the \(\cal{P}\)-bi-separable state satisfies the bound |〈Ψb|G〉|2 ≤ \(2^{ - S\left(\rho _{A}\right)}\), given a subsystem bipartition \(\{ A,\bar {A}\}\). It is not hard to see that these bounds all hold for |Ψf〉, since \(\mathrm{S}_{f}^{\cal{P}} \subset S_{b}^{\cal{P}}\). Thus, one can obtain the finest bound via minimizing over all possible bipartitions and finally get Eq. (8).

The entanglement entropy S(ρA) equals the rank of the adjacency matrix of the underlying bipartite graph, which can be efficiently calculated. Details are discussed in Supplementary Note 1. While the optimization problems can be computationally hard due to the exponential number of possible bipartitions, one can solve it properly as the number of the subsystems m is not too large. In addition, we can always have an upper bound on the minimization by only considering specific partitions. Analytical calculation of the optimization is possible for graph states with certain symmetries, such as the 1-D and 2-D cluster states and the GHZ state.

Proof of Proposition 2

Proof. As shown in Main Text, a graph state |G〉 can be written in the following form

Accordingly, Eq. (11) in Proposition 2 becomes,

Note that the projectors Pl commute with each other, thus we can prove Eq. (26) for all subspaces which are determined by the eigenvalues of all Pl. For the subspace where the eigenvalues of all Pl are 1, the inequality (1 + k − 1) − k ≥ 0 holds. For the subspace where only one of Pl takes value of 0, the inequality (0 + k − 1) − (k − 1) ≥ 0 holds. Moreover, for the subspace in which there are more than one Pl taking 0, the inequality also holds. As a result, we finish the proof.

Proofs of Theorems 1 and 2

Proof of Theorem 1

Proof. The proof is to combine Propositions 1 and 2. Here we only show the proof of Eq. (12), and one can prove Eq. (13) in a similar way. To be specific, one needs to show that any \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state satisfies \(\langle W_{f}^{\cal{P}}\rangle \ge 0\), that is,

Here the first and the second inequalities are right on account of Propositions 2 and 1, respectively.

Proof of Theorem 2

Proof. With Eq. (8) one can bound the fidelity from any \(\cal{P}\)-fully separable state to a graph state |G〉. The m-separable state set Sm contains all the state ρm which can be written as the convex mixture of pure m-separable state, \(\rho _m = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {p_i} \left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_m^i} \right\rangle \left\langle {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_m^i} \right|\), where the partition for each constitute \(\left| {{\mathrm{\Psi }}_m^i} \right\rangle\) needs not to be the same. Hence one can bound the fidelity from ρm to a graph state |G〉 by investigating all possible partitions, i.e.,

where the maximization takes over all possible partitions \({\cal{P}}_{m}\) with m subsystems, the minimization takes over all bipartition of \({\cal{P}}_{m}\). Then like in Eq. (27), by combing Eqs. (11) and (28) we finish the proof.

The optimization problem in Theorem 2 over the partitions is generally hard, since there are about mN/m! possible ways to partition N qubits into m subsystems. For example, when N is large (say, in the order of 70 qubits), the number of different partitions is exponentially large even with a small separability number m. Surprisingly, for several widely used types of graph states, such as 1-D, 2-D cluster states, and the GHZ state, we find the analytical solutions to the optimization problem, as shown in Corollaries in main text.

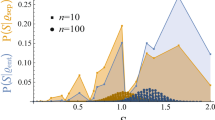

Robustness of entanglement-structure witnesses

In this section, we discuss the robustness of the proposed witnesses in Theorems 1 and 2. In practical experiments, the prepared state ρ deviates from the target graph state |G〉 due to some nonnegligible noise. Here we utilize the following white noise model to quantify the robustness of the witnesses.

which is a mixture of the original state |G〉 and the maximally mixed state with coefficient pnoise. We will find the largest plimit, such that the witness can detect the corresponding entanglement structure when pnoise < plimit. Thus plimit reflects the robustness of the witness.

Let us first consider the entanglement witness \(W_{f}^{\cal{P}}\) in Eq. (12) of Theorem 1. For clearness, we denote \(C_{{\mathrm{min}}} = \min _{\{ A,\bar {A}\} }2^{ - S(\rho _{A})}\). Insert the state of Eq. (29) into the witness, one gets,

where nl = |Vl| is the qubit number in each vertex set with different color, and in the second equality we employ the facts that \({\mathrm{Tr}}(P_l) = 2^{N - n_l}\) and Tr(Pl|G〉〈G|) = 1. Let the above expectation value less than zero, one has

Similarly, for the \(\cal{P}\)-genuine entanglement witness and the non-m-separability witness in Eqs. (13) and (15), we have,

where we denote the optimizations \(\max _{\{ A,\bar {A}\} }2^{ - S(\rho _{A})}\) and \(\max _{{\cal{P}}_{m}}\min _{\{ A,\bar {A}\} }2^{ - S(\rho _{A})}\) as Cmax and Cm, respectively.

Moreover, it is not hard to see that all the coefficients Cmin, Cmax, and Cm are not larger than 0.5. Thus, for any entanglement-structure witness, one has

As a result, our entanglement-structure witness is quite robust to noise, since the largest noise tolerance plimit is just related to the chromatic number of the graph.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Code sharing is not applicable to this article as no code was generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Horodecki, R., Horodecki, P., Horodecki, M. & Horodecki, K. Quantum entanglement. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 865 (2009).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Teleporting an unknown quantum state via dual classical and Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 70, 1895 (1993).

Bennett, C. H. & Brassard, G. in Proceedings of IEEE International Conference on Computers, Systems, and Signal Processing, 175 (India, 1984).

Ekert, A. K. Quantum cryptography based on Bell’s theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 661 (1991).

Brunner, N., Cavalcanti, D., Pironio, S., Scarani, V. & Wehner, S. Bell nonlocality. Rev. Mod. Phys. 86, 419 (2014).

Nielsen, M. A. & Chuang, I. L. Quantum Computation and Quantum Information: 10th Anniversary Edition. 10th edn (Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, 2011).

Lloyd, S. Universal quantum simulators. Science 273, 1073 (1996).

Wineland, D. J., Bollinger, J. J., Itano, W. M., Moore, F. L. & Heinzen, D. J. Spin squeezing and reduced quantum noise in spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. A 46, R6797 (1992).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 010401 (2006).

Monz, T. et al. 14-Qubit entanglement: creation and coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 130506 (2011).

Britton, J. W. et al. Engineered two-dimensional Ising interactions in a trapped-ion quantum simulator with hundreds of spins. Nature 484, 489 EP (2012).

Friis, N. et al. Observation of entangled states of a fully controlled 20-qubit system. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021012 (2018).

Song, C. et al. 10-Qubit entanglement and parallel logic operations with a superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 180511 (2017).

Gong, M. et al. Genuine 12-qubit entanglement on a superconducting quantum processor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 110501 (2019).

Wang, X.-L. et al. Experimental ten-photon entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 210502 (2016).

Chen, L.-K. et al. Observation of ten-photon entanglement using thin BiB3O6 crystals. Optica 4, 77 (2017).

Zhong, H.-S. et al. 12-Photon entanglement and scalable scattershot boson sampling with optimal entangled-photon pairs from parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 250505 (2018).

Lücke, B. et al. Detecting multiparticle entanglement of dicke states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 155304 (2014).

Luo, X.-Y. et al. Deterministic entanglement generation from driving through quantum phase transitions. Science 355, 620 (2017).

Lange, K. et al. Entanglement between two spatially separated atomic modes. Science 360, 416 (2018).

Dür, W., Vidal, G. & Cirac, J. I. Three qubits can be entangled in two inequivalent ways. Phys. Rev. A 62, 062314 (2000).

Acín, A., Bruß, D., Lewenstein, M. & Sanpera, A. Classification of mixed three-qubit states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 040401 (2001).

Guhne, O., Toth, G. & Briegel, H. J. Multipartite entanglement in spin chains. New J. Phys. 7, 229 (2005).

Huber, M. & de Vicente, J. I. Structure of multidimensional entanglement in multipartite systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 030501 (2013).

Shahandeh, F., Sperling, J. & Vogel, W. Structural quantification of entanglement. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 260502 (2014).

Lu, H. et al. Entanglement structure: entanglement partitioning in multipartite systems and its experimental detection using optimizable witnesses. Phys. Rev. X 8, 021072 (2018).

Cirac, J. I., Ekert, A. K., Huelga, S. F. & Macchiavello, C. Distributed quantum computation over noisy channels. Phys. Rev. A 59, 4249 (1999).

Kimble, H. J. The quantum internet. Nature 453, 1023 (2008).

Terhal, B. M. A family of indecomposable positive linear maps based on entangled quantum states. Linear Algebra Appl. 323, 61 (2001).

Guhne, O. & Toth, G. Entanglement detection. Phys. Rep. 474, 1 (2009).

Friis, N., Vitagliano, G., Malik, M. & Huber, M. Entanglement certification from theory to experiment. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 72 (2019).

Gühne, O., Lu, C.-Y., Gao, W.-B. & Pan, J.-W. Toolbox for entanglement detection and fidelity estimation. Phys. Rev. A 76, 030305(R) (2007).

Zhou, Y., Guo, C. & Ma, X. Decomposition of a symmetric multipartite observable. Phys. Rev. A 99, 052324 (2019).

Tóth, G. & Gühne, O. Detecting genuine multipartite entanglement with two local measurements. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 060501 (2005).

Knips, L., Schwemmer, C., Klein, N., Wieśniak, M. & Weinfurter, H. Multipartite entanglement detection with minimal effort. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 210504 (2016).

Wang, Y., Li, Y., Yin, Z.-q & Zeng, B. 16-qubit IBM universal quantum computer can be fully entangled. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 46 (2018).

Briegel, H. J. & Raussendorf, R. Persistent entanglement in arrays of interacting particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 910 (2001).

Hein, M. et al. Entanglement in graph states and its applications. http://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0602096 (2006).

Raussendorf, R. & Briegel, H. J. A one-way quantum computer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5188 (2001).

Raussendorf, R., Browne, D. E. & Briegel, H. J. Measurement-based quantum computation on cluster states. Phys. Rev. A 68, 022312 (2003).

Schlingemann, D. & Werner, R. F. Quantum error-correcting codes associated with graphs. Phys. Rev. A 65, 012308 (2001).

Gühne, O., Tóth, G., Hyllus, P. & Briegel, H. J. Bell inequalities for graph states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 120405 (2005).

Zeng, B., Chen, X., Zhou, D.-L. & Wen, X.-G. Quantum information meets quantum matter—from quantum entanglement to topological phase in many-body systems. https://arxiv.org/abs/1508.02595 (2015).

Eisert, J., Cramer, M. & Plenio, M. B. Colloquium: area laws for the entanglement entropy. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 277 (2010).

Gottesman, D. Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. arXiv: quant-ph/9705052. https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/9705052 (1997).

Rossi, M., Huber, M., BruB, D. & Macchiavello, C. Quantum hypergraph states. New J. Phys. 15, 113022 (2013).

Orus, R. A practical introduction to tensor networks: matrix product states and projected entangled pair states. Ann. Phys. 349, 117 (2014).

Carleo, G. & Troyer, M. Solving the quantum many-body problem with artificial neural networks. Science 355, 602 (2017).

Deng, D.-L., Li, X. & Das Sarma, S. Quantum entanglement in neural network states. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021021 (2017).

Sørensen, A. S. & M, K. Entanglement and extreme spin squeezing. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4431 (2001).

Wölk, S. & Gühne, O. Characterizing the width of entanglement. New J. Phys. 18, 123024 (2016).

Branciard, C., Rosset, D., Liang, Y.-C. & Gisin, N. Measurement-device-independent entanglement witnesses for all entangled quantum states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 060405 (2013).

Liang, Y.-C. et al. Family of bell-like inequalities as device-independent witnesses for entanglement depth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 190401 (2015).

Zhao, Q., Yuan, X. & Ma, X. Efficient measurement-device-independent detection of multipartite entanglement structure. Phys. Rev. A 94, 012343 (2016).

Dimic, A. & Dakic, B. Single-copy entanglement detection. npj Quantum Inf. 4, 11 (2018).

Saggio, V. et al. Experimental few-copy multipartite entanglement detection. Nat. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0550-4 (2019).

Bourennane, M. et al. Experimental detection of multipartite entanglement using witness operators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 087902 (2004).

Hein, M., Eisert, J. & Briegel, H. J. Multiparty entanglement in graph states. Phys. Rev. A 69, 062311 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Y.-C. Liang for the insightful discussions. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant Nos. 11875173 and 11674193, and the National Key R&D Program of China Grant Nos. 2017YFA0303900 and 2017YFA0304004, and the Zhongguancun Haihua Institute for Frontier Information Technology. Xiao Yuan was supported by the EPSRC National Quantum Technology Hub in Networked Quantum Information Technology (EP/M013243/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and X.M. initialized the project. Y.Z., Q.Z., and X.Y. developed the idea and formulated the problem as it is presented. X.M. supervised the project. All authors contributed to deriving the results and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Zhao, Q., Yuan, X. et al. Detecting multipartite entanglement structure with minimal resources. npj Quantum Inf 5, 83 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0200-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0200-9

This article is cited by

-

On the structure of mirrored operators obtained from optimal entanglement witnesses

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Partial transpose moments, principal minors and entanglement detection

Quantum Information Processing (2023)

-

A scheme to create and verify scalable entanglement in optical lattice

npj Quantum Information (2022)

-

Optimized search for complex protocols based on entanglement detection

Quantum Information Processing (2022)

-

Multipartite uncertainty relation with quantum memory

Scientific Reports (2021)