Abstract

Discounting is a manifestation of behavioral impulsivity, which is closely related to self-regulation processes. The decision-making process for intertemporal choices is governed by the inhibition of impulses, which can influence both risk and time-related attitudes. This paper utilizes self-reported measures of risk, impatience, and impulsivity attitudes to examine their impact on the implicit discount rate used when weighing the current purchase cost against future energy savings of appliances. It analyzes and tests the interplay between these attitudes using specific functional forms and causal models. The results highlight the role of risk, impatience and impulsivity on the discount rate and the biases that arise from omitting impulsive attitudes. In addition, other factors such as environmental and social preferences, attitudes, and financial constraints contribute to the implicit discount rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data generated by the survey are available upon request to the author.

Notes

Self-control is a top-down or Type II deliberate process which entails (a) a conflicting dilemma of deciding between a concrete-proximal goal and an abstract-distal goal and/or (b) overcoming a stimulus-driven response to execute a goal-relevant response (Nigg, 2017). It is a specific self-regulation case where goals are competing (Fujita, 2011).

Smaller delayed rewards are discounted more steeply than larger delayed rewards. Smaller probabilistic rewards are less steeply discounted than larger probabilistic rewards.

Households which had made a purchase more than 4 years earlier were not included.

Houston (1983) used a “very long useful life” to define lifetime, a hypothetical device, total costs of purchase and installation. Here the lifetime was held constant at 10 years. This figure coincides with the central values for the expected duration of a washing machine for households, as per Table 10.

The internal rate of return is calculated with R software using the FinCal package.

No significant multicollinearity was observed in this model. However, there is a possibility of collinearity occurring among the variables of risk, impatience, and impulsivity, as they may be influenced by other variables in the model. Nevertheless, this effect is not substantial, as indicated by the results of the variance inflation test presented in Table 12 in the appendix.

No sample selection bias was detected in the model based on a two-step Heckman procedure.

See Table 11—Models M1 B and M1 C.

The introduction of a cross term between environmental worries and installation of EE windows was not conclusive.

Income has been measured as a self-reported evaluation of relative income (Table 8). The absolute income presents greater missing values and had no significant effect in this model.

The magnitude effect is observed for both delay discounting and probabilistic discounting but operates differently. Smaller delayed amounts are discounted more steeply than larger delayed amounts. Smaller probabilistic amounts are discounted less steeply than larger probabilistic amounts (Green and Myerson, 2004).

References

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & I’Haridon, O. (2013). Sign-dependence in intertemporal choice. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47, 225–253.

Allcott, H. (2011). Consumers’ Perceptions and Misperceptions of Energy Costs. American Economic Review, 101, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.98

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2008). Eliciting Risk and Time Preferences. Econometrica, 76, 583–618. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0262.2008.00848.x

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2013). Discounting behaviour and the magnitude effect: Evidence from a field experiment in Denmark. Economica, 80, 670–697. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12028

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure Altruism and Donations to Public Goods: A Theory of Warm-Glow Giving. The Economic Journal, 100, 464. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Andreoni, J. (1995). Warm-Glow versus Cold-Prickle: The Effects of Positive and Negative Framing on Cooperation in Experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118508

Augenblick, N., Niederle, M., & Sprenger, C. (2015). Working over Time: Dynamic Inconsistency in Real Effort Tasks *. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130, 1067–1115. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv020

Benzion, U., Rapoport, A., & Yagil, J. (1989). Discount Rates Inferred from Decisions: An Experimental Study. Management Science, 35, 270–284.

Berns, G., Laibson, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2007). Intertemporal choice – toward an integrative framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 482–488.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. (2001). Do People Mean What They Say? Implications for Subjective Survey Data. American Economic Review, 91, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.2.67

Bixter, M. T., & Luhmann, C. C. (2015). Evidence for Implicit Risk: Delay Facilitates the Processing of Uncertainty. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 28, 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.1853

Blasch, J., Filippini, M., & Kumar, N. (2019). Boundedly rational consumers, energy and investment literacy, and the display of information on household appliances. Resource and Energy Economics, Recent Advances in the Economic Analysis of Energy Demand - Insights for Industries and Households, 56, 39–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reseneeco.2017.06.001

Brent, D. A., & Ward, M. B. (2018). Energy efficiency and financial literacy. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 90, 181–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2018.05.004

Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The Influence of a Sense of Time on Human Development. Science, 312, 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

Coller, M., & Williams, M. B. (1999). Eliciting Individual Discount Rates. Experimental Economics, 2, 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009986005690

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Golsteyn, B. H. H., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2017). Risk Attitudes Across The Life Course. The Economic Journal, 127, F95–F116. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12322

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual Risk Attitudes: Measurement, Determinants, and Behavioral Consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9, 522–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x

Estle, S. J., Green, L., Myerson, J., & Holt, D. D. (2006). Differential effects of amount on temporal and probability discounting of gains and losses. Memory & Cognition, 34, 914–928. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193437

Fineberg, N. A., Chamberlain, S. R., Goudriaan, A. E., Stein, D. J., Vanderschuren, L. J. M. J., Gillan, C. M., Shekar, S., Gorwood, P. A. P. M., Voon, V., Morein-Zamir, S., Denys, D., Sahakian, B. J., Moeller, F. G., Robbins, T. W., & Potenza, M. N. (2014). New developments in human neurocognition: clinical, genetic, and brain imaging correlates of impulsivity and compulsivity. CNS Spectrums, 19, 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852913000801

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive Reflection and Decision Making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196732

Frederick, S., Loewenstein, G., & O’Donoghue, T. (2002). Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review. Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 351–401. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161311

Fredslund, E. K., Mørkbak, M. R., & Gyrd-Hansen, D. (2018). Different domains – Different time preferences? Social Science & Medicine, 207, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.04.052

Frey, R., Pedroni, A., Mata, R., Rieskamp, J., & Hertwig, R. (2017). Risk preference shares the psychometric structure of major psychological traits. Science Advances, 3, e1701381. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1701381

Fudenberg, D., & Levine, D. K. (2006). A Dual-Self Model of Impulse Control. American Economic Review, 96, 1449–1476. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.5.1449

Fujita, K. (2011). On Conceptualizing Self-Control as More Than the Effortful Inhibition of Impulses. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 352–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311411165

Gabaix, X., Laibson, D., Moloche, G., & Weinberg, S. (2006). Costly Information Acquisition: Experimental Analysis of a Boundedly Rational Model. The American Economic Review, 96, 34.

Gadenne, D., Sharma, B., Kerr, D., & Smith, T. (2011). The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviours. Energy Policy, Clean Cooking Fuels and Technologies in Developing Economies, 39, 7684–7694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.09.002

Gerarden, T. D., Newell, R. G., & Stavins, R. N. (2017). Assessing the Energy-Efficiency Gap. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 1486–1525. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20161360

Green, L., & Myerson, J. (2004). A Discounting Framework for Choice With Delayed and Probabilistic Rewards. Psychol Bull, 130, 769–792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.769

Green, L., & Myerson, J. (2013). How Many Impulsivities? A Discounting Perspective. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 99, 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.1

Green, L., Myerson, J., & Mcfadden, E. (1997). Rate of temporal discounting decreases with amount of reward. Memory & Cognition, 25, 715–723. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03211314

Green, L., Myerson, J., Oliveira, L., & Chang, S. E. (2013). Delay Discounting of Monetary Rewards over a Wide Range of Amounts. Journal of the experimental analysis of behavior, 100, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeab.45

Hamilton, K. R., Littlefield, A. K., Anastasio, N. C., Cunningham, K. A., Fink, L. H. L., Wing, V. C., Mathias, C. W., Lane, S. D., Schütz, C. G., Swann, A. C., Lejuez, C. W., Clark, L., Moeller, F. G., & Potenza, M. N. (2015a). Rapid-response impulsivity: definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders, 6, 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000100

Hamilton, K. R., Mitchell, M. R., Wing, V. C., Balodis, I. M., Bickel, W. K., Fillmore, M., Lane, S. D., Lejuez, C. W., Littlefield, A. K., Luijten, M., Mathias, C. W., Mitchell, S. H., Napier, T. C., Reynolds, B., Schütz, C. G., Setlow, B., Sher, K. J., Swann, A. C., Tedford, S. E., … Moeller, F. G. (2015b). Choice impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders, 6, 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000099

Hausman, J. A. (1979). Individual Discount Rates and the Purchase and Utilization of Energy-Using Durables. Bell Journal of Economics, 10, 33–54.

Hermann, D., & Musshoff, O. (2016). Anchoring effects in experimental discount rate elicitation. Applied Economics Letters, 23, 1022–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2015.1128072

Hertwig, R., Wulff, D. U., & Mata, R. (2019). Three gaps and what they may mean for risk preference. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 374, 20180140. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0140

Heutel, G. (2019). Prospect theory and energy efficiency. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 96, 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2019.06.005

Houston, D. A. (1983). Implicit Discount Rates and the Purchase of Untried, Energy-Saving Durable Goods. Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1086/208962

Jaffe, A. B., & Stavins, R. N. (1994). The energy paradox and the diffusion of conservation technology. Resource and Energy Economics, 16, 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/0928-7655(94)90001-9

Johnson, K. L., Bixter, M. T., & Luhmann, C. C. (2020). Delay discounting and risky choice: Meta-analytic evidence regarding single-process theories. Judgment and Decision Making, 15, 381–400.

Linares, P., & Labandeira, X. (2010). Energy Efficiency: Economics and Policy. Journal of Economic Surveys, 24, 573–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6419.2009.00609.x

Löckenhoff, C. E., O’Donoghue, T., & Dunning, D. (2011). Age differences in temporal discounting: The role of dispositional affect and anticipated emotions. Psychology and Aging, 26, 274–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023280

Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (1992). Anomalies in Intertemporal Choice: Evidence and an Interpretation. Q J Econ, 107, 573–597. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118482

Lowry, R., & Peterson, M. (2011). Pure Time Preference. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 92, 490–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0114.2011.01408.x

Mata, R., Frey, R., Richter, D., Schupp, J., & Hertwig, R. (2018). Risk Preference: A View from Psychology. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32, 155–172. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.32.2.155

Megías-Robles, A., Cándido, A., Maldonado, A., Baltruschat, S., & Catena, A. (2022). Differences between risk perception and risk-taking are related to impulsivity levels. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 22, 100318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100318

Meier, A. N. (2022). Emotions and risk attitudes. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14, 527–558. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200164

Meier, S., & Sprenger, C. D. (2015). Temporal Stability of Time Preferences. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 97, 273–286. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00433

Mishra, S., & Lalumière, M. L. (2017). Associations between delay discounting and risk-related behaviors, traits, attitudes, and outcomes. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 30, 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.2000

Mitchell, S. H., & Wilson, V. B. (2010). The subjective value of delayed and probabilistic outcomes: Outcome size matters for gains but not for losses. Behav Processes, 83, 36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.003

Nauges, C., & Wheeler, S. A. (2017). The Complex Relationship Between Households’ Climate Change Concerns and Their Water and Energy Mitigation Behaviour. Ecological Economics, 141, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.05.026

Newell, R. G., & Siikamäki, J. (2015). Individual Time Preferences and Energy Efficiency. American Economic Review, 105, 196–200. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20151010

Nigg, J. T. (2017). Annual Research Review: On the relations among self-regulation, self-control, executive functioning, effortful control, cognitive control, impulsivity, risk-taking, and inhibition for developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12675

Ostaszewski, P., Green, L., & Myerson, J. (1998). Effects of inflation on the subjective value of delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 5, 324–333. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03212959

Qiu, Y., Colson, G., & Grebitus, C. (2014). Risk preferences and purchase of energy-efficient technologies in the residential sector. Ecological Economics, 107, 216–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2014.09.002

Rachlin, H., Logue, A. W., Gibbon, J., & Frankel, M. (1986). Cognition and behavior in studies of choice. Psychological Review, 93, 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.93.1.33

Sallee, J. M. (2014). Rational Inattention and Energy Efficiency. The Journal of Law and Economics, 57, 781–820. https://doi.org/10.1086/676964

Samuelson, P. (1937). A Note on Measurement of Utility. The Review of Economic Studies, 4, 155. https://doi.org/10.2307/2967612

Schildberg-Hörisch, H. (2018). Are Risk Preferences Stable? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32, 135–154. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.32.2.135

Schleich, J., Gassmann, X., Faure, C., & Meissner, T. (2016). Making the implicit explicit: A look inside the implicit discount rate. Energy Policy, 97, 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2016.07.044

Schleich, J., Gassmann, X., Meissner, T., & Faure, C. (2019). A large-scale test of the effects of time discounting, risk aversion, loss aversion, and present bias on household adoption of energy-efficient technologies. Energy Economics, 80, 377–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2018.12.018

Shama, A. (1983). Energy conservation in US buildings: Solving the high potential/low adoption paradox from a behavioural perspective. Energy Policy, 11, 148–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-4215(83)90027-7

Stadelmann, M. (2017). Mind the gap? Critically reviewing the energy efficiency gap with empirical evidence. Energy Research & Social Science, 27, 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.03.006

Thaler, R. (1981). Some empirical evidence on dynamic inconsistency. Economics Letters, 8, 201–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1765(81)90067-7

Train, K. (1985). Discount rates in consumers’ energy-related decisions: A review of the literature. Energy, 10, 1243–1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/0360-5442(85)90135-5

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model. Q J Econ, 106, 1039–1061. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937956

van der Linden, S. (2017). Determinants and Measurement of Climate Change Risk Perception, Worry, and Concern. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication. Oxford University Press.

Vischer, T., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Schupp, J., Sunde, U., & Wagner, G. G. (2013). Validating an ultra-short survey measure of patience. Economics Letters, 120, 142–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.04.007

Weber, E. U., Blais, A.-R., & Betz, N. E. (2002). A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15, 263–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.414

Wittmann, M., & Paulus, M. P. (2008). Decision making, impulsivity and time perception. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12, 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.004

Yap, S. C. Y., Wortman, J., Anusic, I., Baker, S. G., Scherer, L. D., Donnellan, M. B., & Lucas, R. E. (2017). The Effect of Mood on Judgments of Subjective Well-Being: Nine Tests of the Judgment Model. J Pers Soc Psychol, 113, 939–961. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000115

Zuckerman, M., & Kuhlman, D. M. (2000). Personality and Risk-Taking: Common Bisocial Factors. Journal of Personality, 68, 999–1029. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00124

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 program under grant agreement Nº 723741—CONSEED. It is also supported by María de Maeztu Excellence Unit 2023-2027 (Ref. CEX2021-001201-M), funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033; and by the Basque Government through the BERC 2022-2025 program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. There is no conflicts of interest associated with this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendices

A. Description of variables and descriptive statistics

The description of the variable in Table 8 includes its name in the table of results, its description, and format.

Descriptive statistics

Tables 9 and 10 present the descriptive statistics of the variables of the models.

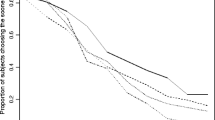

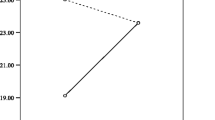

B. Robustness of the model: independence with inclusion of factors

To check how the size and significance of the marginal effects change, different determinants of the IDR are successively included in the IDR equation, as per models 1 to 7 in Table 11. Results show that the IDR model tends to be stable with the inclusion of other factors, especially when impulsivity is included.

Model 1A–C restrict the factors to risk, impatience, and impulsivity attitudes. Model 2 adds social preferences, attitudes, and comparison. Model 3 adds informational factors to the previous model. Model 4 further adds financial and economic factors. Model 5 tests only individual characteristics, while Model 6 adds financial and economic factors to the previous model. Model 7 represents the complete model presented in the main text.

The model specification remains relatively stable when other parameters are included. The inclusion of impulsivity in Model 1C makes the risk variable significant. The effects of age, gender, and life satisfaction disappear when other variables are included (Model 5 vs. Models 6–7).

C. Tests of multicollinearity

Table 12 presents the results of the multicollinearity test conducted using the variance inflation factor.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Foudi, S. Are risk attitude, impatience, and impulsivity related to the individual discount rate? Evidence from energy-efficient durable goods. Theory Decis (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-023-09961-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-023-09961-9