Abstract

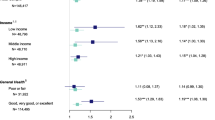

Little is known regarding the health outcomes of people who exit from housing assistance and if that experience varies by the circumstances under which a person exits. We asked two questions: (1) does the type of exit from housing assistance matter for healthcare utilization? And (2) how does each exit type compare to remaining in housing assistance in terms of healthcare utilization? This retrospective cohort study of 5550 exits between 2012 and 2018 used data from two large, urban public housing authorities in King County, Washington. Exposures were exiting from housing assistance and type of exit (positive, neutral, negative). Outcomes were emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and well-child checks (among those aged < 6) in the year following exit from housing assistance. After adjustment for demographics and baseline healthcare utilization, people with positive exits had 26% (95% confident interval: 6–39%) lower odds of having 1 + ED visits in the year following exit than people with negative exits and 20% (95% CI: 6–31%) lower odds than those who continued receiving housing assistance. Neutral and negative exits did not differ substantially from each other, and both exit types appear to be detrimental to health, with higher levels of ED visits and hospitalizations and lower levels of well-child checks. Why people exit from housing assistance matters. Those with negative exits experience poorer outcomes and efforts should be made to both prevent this kind of exit and mitigate its impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:397–418.

Krieger J, Higgins DL. Housing and health: time again for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):758–68.

Quensell ML, Taira DA, Seto TB, Braun KL, Sentell TL. “I need my own place to get better”: patient perspectives on the role of housing in potentially preventable hospitalizations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28(2):784–97.

Wright B, Li G, Weller M, Vartanian K. Health in housing: exploring the intersection between housing and health care. Portland, OR: Center for Outcomes Research and Education (CORE); 2016.

Pollack CE, Blackford AL, Du S, Deluca S, Thornton RLJ, Herring B. Association of receipt of a housing voucher with subsequent hospital utilization and spending. JAMA. 2019;322(21):2115–24.

Simon AE, Fenelon A, Helms V, et al. HUD housing assistance associated with lower uninsurance rates and unmet medical need. Health Aff. 2017;36:1016–23.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Fiscal Year 2022-2026 Strategic Plan. Washington: USDHUD; 2022.

Biederman DJ, Callejo-Black P, Douglas C, O’Donohue HA, Daeges M, Sofela O, et al. Changes in health and health care utilization following eviction from public housing. Public Health Nurs. 2022;39(2):363–71.

Schwartz GL, Feldman JM, Wang SS, Glied SA. Eviction, healthcare utilization, and disenrollment among New York City Medicaid patients. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62(2):157–64.

Richter FGC, Coulton C, Urban A, Steh S. An integrated data system lens into evictions and their effects. Hous Policy Debate. 2021;0(0):1–23.

Smith RE, Popkin SJ, George T, Comey J. What happens to housing assistance leavers? Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2014.

Simsek M, Costa R, de Valk HAG. Childhood residential mobility and health outcomes: a meta-analysis. Health Place. 2021;71:102650.

Lunsky Y, Elserafi J. Life events and emergency department visits in response to crisis in individuals with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2011;55(7):714–8.

Sonne W. Dwelling in the metropolis: reformed urban blocks 1890–1940 as a model for the sustainable compact city. Prog Plann. 2009;72(2):53–149.

Finkelstein A, Gentzkow M, Williams H. Sources of geographic variation in health care: evidence from patient migration*. Q J Econ. 2016;131(4):1681–726.

McClure K. Length of stay in assisted housing. Washington, DC: HUDUSER; 2017.

Scott KW, Liu A, Chen C, Kaldjian AS, Sabbatini AK, Duber HC, et al. Healthcare spending in U.S. emergency departments by health condition, 2006–2016. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258182.

Mkanta WN, Chumbler NR, Yang K, Saigal R, Abdollahi M. Cost and predictors of hospitalizations for ambulatory care - sensitive conditions among Medicaid enrollees in comprehensive managed care plans. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol. 2016;3:2333392816670301.

Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff. 2010;29(9):1630–6.

Public Health - Seattle & King County, King County Housing Authority, Seattle Housing Authority. King County Data Across Sectors for Housing and Health, 2018. Seattle, WA: King County; 2018.

Hinds AM, Bechtel B, Distasio J, Roos LL, Lix LM. Public housing and healthcare use: an investigation using linked administrative data. Can J Public Health. 2019;110(2):127–38.

Headen IE, Dubbin L, Canchola AJ, Kersten E, Yen IH. Health care utilization among women of reproductive age living in public housing: associations across six public housing sites in San Francisco. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101797.

Turner MA, Kingsley GT. Federal programs for addressing low-income housing needs. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2008.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Strategic Plan 2018-2022. Washington, DC: USDHUD;2019.

Washington State Health Care Authority. Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) Measurement Guide. 2022. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/program/mtp-measurement-guide.pdf. Accessed 25 Jul 2022.

Washington State Health Care Authority. EPSDT Well-child checkups for your child or teen. 2020. https://www.hca.wa.gov/assets/free-or-low-cost/19-0056-epsdt-well-child-checkups.pdf. Accessed 8 Aug 2022.

Matheson AI, Colombara DV, Pennucci A, Chan A, Shannon T, Suter M, et al. Seeing the big picture with multi-sector data: factors associated with exiting from federal housing assistance by exit type. Cityscape. 2023;25(2):289–309.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Chronic conditions data warehouse. 2022. https://www2.ccwdata.org/web/guest/condition-categories-chronic. Accessed 15 Jun 2022.

RStudio Team. Rstudio: integrated development environment for R. Boston, MA: RStudio, Inc; 2022.

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2022.

Cairns C, Ashman JJ, Kang K. Emergency department visit rates by selected characteristics: united States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;434:1–8.

Harron K, Dibben C, Boyd J, Hjern A, Azimaee M, Barreto ML, et al. Challenges in administrative data linkage for research. Big Data Soc. 2017;4(2):2053951717745678. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951717745678.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development under funding opportunity FR-6400-N-58.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Matheson, A.I., Colombara, D.V., Pennucci, A. et al. A Good Farewell? Positive Exits from Federal Housing Assistance and Lower Acute Healthcare Utilization. J Urban Health 100, 1202–1211 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00789-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-023-00789-w