Abstract

The societal value of non-profit organizations (NPOs) and the enabling aspect of digital transformations (DTs) pinpoint these as cornerstones in our running after sustainable development goals (SDGs). However, applying DT to NPOs foreshadows outstanding but untapped opportunities to enhance our capacity to meet those goals. This paper shed light on those opportunities by exploring the DT of a food redistribution charity which commits to reach zero hunger in London, the United Kingdom. Our results not only highlight the importance of studying DT in the setting of sustainable-oriented NPOs but also reveal the key role of leadership, entrepreneurship, agile management, co-creation, user-friendliness, and building a data-driven learning culture to strengthen its impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In a recent paper, George et al. (2021) picture a convergence between two seemingly disparate trends. The first is what they call the “sustainability imperative”: The heightened attention to sustainability and the need for societal actors to take expanded roles in the production of social and environmental value. The second is the “digital imperative”: The disruptive process of organizational and social change triggered off by the diffusion of SMACIT (social, mobile, analytics, cloud, and Internet of Things) (Hanelt et al., 2021). To this end, the EU Commission has recently coined the concept of twin transition to stress the importance of managing those transformations together (Muench et al., 2022). In this picture, social entrepreneurs and NPOs are seen as key to realize the potential of sustainability inherent in the development of SMACIT (George et al., 2021), since those two transitions may clash (Muench et al., 2022). Next to that, digital technologies are resource intensive, create waste, and generate new forms of discrimination and social exclusion. More specifically, the peculiar sight and capacity of those entrepreneurs and organizations to apply business logic to tackle social and environmental issues are seen as a powerful source of additional value (Cabral et al., 2019) and an important safeguard against possible drifts in the development of those technologies (George et al., 2021). For instance, the case of Fairbnb shows how social entrepreneurship may limit the negative impacts associated with the development of global house-sharing platforms in over-touristed cities.

Even if the potential contribution of social entrepreneurship and NPOs to the twin transition starts to be recognized, there is not yet literature addressing how DT takes place and how it is managed in NPOs. However, DT in NPOs is important for at least two reasons. First, DT is a construct that originated in the for-profit sector. Thus, it is important to understand what dynamics the adoption of this construct may trigger off in the context of NPOs, since there are some inherent differences like organizational vision, strategic and financial constraints (Euske, 2003; Hull & Lio, 2006). Two aspects are deserving particular attention: the automation associated with the adoption of those technologies, and the nature of NPOs as a workplace, which combines conventional employment and volunteering. Second, DT relies upon more lean and agile methodologies, which aim at supporting a more open, interactive, and inclusive stakeholders’ participation to collectively mobilize and engage in organizational change (Sharma et al., 2021; Upadhyay et al., 2022). This shows the importance to understand how those methodologies, aiming at supporting and strengthening collective participation and collaboration, perform in a non-profit setting. Therefore, this study aims to address the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the main challenges and dynamics DT triggers off in the context of NPOs, especially regarding the specific system values and motivations underpinning participations and collaborations in NPOs?

-

2.

How do lean and agile methodologies, which are often associated with DT, perform and contribute to collaboration and participation in NPOs?

To answer those questions, we applied a grounded theory to a single case study. Grounded theory is a qualitative method particularly suited to conduct explorative research on social processes that have attracted little attention from previous research. Our prior reading has focused on two issues: DT and the strategic approach applied to NPOs (Cabral et al., 2019; Laurett & Ferreira, 2018; Maier et al., 2016). The case being studied is The Felix Project which is one of the biggest food redistribution charities in London, with food provided for roughly 30 million meals in 2021.Footnote 1 The Felix Project initially started a project regarding its route planning process to create a seamless experience for its volunteering drivers. Though, soon it developed into a much bigger project requesting a platform to improve the efficiency of multiple elements of its process management.

Our study produces three major contributions to our current understanding of the management of DT in an NPO. First, the importance of entrepreneurship and agile management supported by leadership to foster openness to change in an NPO with a community of volunteers that have a wide variety of competencies, experiences, and aspirations. Second, the role of co-creation and its human-centered methods to support the verbalization of knowledge and strengthen the sense of mutual belonging in NPOs. Third, stimulating the adoption of a data-driven learning culture to constantly renovate the base of participation in NPOs.

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the “Background literature” Section, we lay the foundation of our study: an extensive analysis of the background literature regarding DTs and NPOs, and the latter’s role in achieving sustainability. In the “Methodology” Section, we discuss our methodology including data collection and analysis methods. In the “Findings” Section, the main findings of the case study are presented which are then discussed in the “Discussion” Section while highlighting the main limitations of this study. Lastly, we reflect on the research question and summarize the study in the “Conclusion” Section.

Background Literature

Principally, digital transformation is not solely about digital technology (Tabrizi et al., 2019). Differently, DT is defined as “organizational change that is triggered off and shaped by the widespread diffusion of digital technologies” (Hanelt et al., 2021, p. 1160). The kind of organizational change driven by those technologies cannot be equated to that of traditional information and communication technologies. This is because it is inherently incomplete, spans to a wider ecosystem and is disruptive in nature. Thus, DT is a strategic process aiming to change and innovate organizational boundaries, market relationships, and stewardship through digital technologies (George et al., 2021; Hanelt et al., 2021; Tabrizi et al., 2019).

However, DT does not only change the strategy of organizations but also the way those operate internally and externally. DT strategies are often associated with the adoption of lean and agile approaches to management (Centobelli et al., 2020; Moi & Cabiddu, 2021). Those methodologies implement an experimental approach to management, which aims to maximize the organizational responsiveness to change and minimize waste through frequent and continuous processes of trial and error (Sharma et al., 2021; Upadhyay et al., 2022). Organizations are trained to learn and change in response to the feedback received from their partners and the market.Footnote 2 Lately, this method is being widely applied, also in the development of sustainability-focused business models (Sharma et al., 2021; Upadhyay et al., 2022). Those methods heavily rely on extensive collaboration and regard people as the organization’s most valuable asset (Sakthi Nagaraj & Jeyapaul, 2021; Upadhyay et al., 2022). Thus, NPOs, as an organizational context in which care and engagement are key to motivating people to participate, can be the place where those principles can be fully implemented.

There is not yet sufficient literature focusing on DT in NPOs. However, given the strategic and innovative nature of DT, we can derive some initial insights on the possible challenges and dynamics associated with the adoption of DT in NPOs by looking at literature about strategic management in NPOs (Cabral et al., 2019; Laurett & Ferreira, 2018; Maier et al., 2016). There are several concepts describing the phenomena of NPOs becoming business-like (Maier et al., 2016). Most have been developed related to core and support processes in NPOs. Examples are managerialization, corporatization, marketization, and more recently social enterprise and entrepreneurship, and professionalization. Those different perspectives and definitions can be summarized into the concept of hybrid organizations (Evers, 2005), which emphasizes the merging of logics between private and public sector organizations as two opposite ideal types that are co-shaping characteristics that have been and will remain of NPOs (Brandsen et al., 2005; Evers, 2020). This is because NPOs are growing at the intersection between domains like community, market, and state that are equally different to grasp and whose boundaries are blurring.

While the origins of this literature can be traced back to the 1980s, it was in the early 2000s that the focus shifted from understanding how the application of business-like methodologies affects the nature of NPOs to exploring its influence on specific processes such as innovation, human resources management, and entrepreneurship (Laurett & Ferreira, 2018). Notably, there has been significant emphasis on studying the management of innovation within NPOs. This is driven by several factors, including increasing competitive pressures and the need for greater efficiency (Jaskyte, 2015), the complementary role NPOs play alongside FPOs (Phillips et al., 2015), and the growing recognition of social entrepreneurship and innovation as alternatives to traditional corporate social responsibility approaches (van der Have & Rubalcaba, 2016; Zahra et al., 2009) and NPOs’ managerial practices (Andersson & Self, 2015).

These studies provide insights into the unique aspects of managing innovation in NPOs (do Adro & Fernandes, 2021). Leadership plays a crucial role in managing collaboration among diverse stakeholders (Taylor, 2015; Woo et al., 2022), ensuring the legitimacy and commitment to the original mission of NPOs (do Adro & Fernandes, 2021), and fostering an innovative culture within the organization (do Adro et al., 2022). However, unlike FPOs, NPOs often face challenges in terms of lacking internal competencies required to lead innovation processes (Hull & Lio, 2006). Additionally, NPOs encounter complexity due to the distinctive nature of employment relationships (Aboramadan et al., 2022; do Adro & Leitão, 2020). On the one hand, employees in NPOs may express discontent as innovation is often perceived as imposed by top management, and skilled volunteers often occupy leading positions in the organizations (do Adro & Fernandes, 2021). On the other hand, innovation may impact the relationship with volunteers involved in day-to-day operations (Oliveira et al., 2021). Therefore, the organizational context and internal marketing are crucial in fostering motivation and commitment among all individuals, regardless of their employment or volunteer status (Sanzo et al., 2015). The commitment of employees and volunteers becomes even more significant in the context of DT, where leveraging internal competencies and ensuring employee engagement are considered vital for the success of this strategy (Tabrizi et al., 2019).

In conclusion, DT in FPOs is recognized as a disruptive and innovative strategy that fundamentally reshapes organizational operations and mission pursuit. While the literature on DT in NPOs is still limited, existing studies on innovation management in NPOs and social entrepreneurship offer valuable insights that can inform the exploration of DT in NPOs. Key considerations include the pivotal role of leadership and the establishment of a learning culture to sustain NPOs’ long-term innovation capabilities. Additionally, potential conflicts arising from the adoption of innovative practices within NPOs should be acknowledged, such as vertical conflicts between leadership and employees, as well as conflicts related to the evolving competencies and skills required for active engagement within the organization, encompassing both employees and volunteers. These insights will serve as a guiding framework for the forthcoming analysis of our case study, enabling a deeper understanding of the implications and dynamics of DT in NPOs.

Methodology

Research Design

In this paper, a grounded theory method is embraced within a single case study strategy, relying on an interpretivist approach adopting the inductive logic, using interviews as the main data collection technique. The integration of a grounded theory method and a single case study strategy is justified (Halaweh et al., 2008) as using data to conceptualize an understanding of empirical observations within the case study (Silverman, 2014) allows for the generation of a theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1998; Thomas, 2006). Additionally, its qualitative characteristic supports the exploration of areas that are lacking extensive research (Saunders et al., 2007) and therefore is deemed applicable since the research on DTs in NPOs is still in its infancy.

The study setting is the case of The Felix Project adopting a mobile application, a data monitoring software, and a CRM system. This is an NPO that collects food and delivers it to charities, schools, and local community organizations in London to turn it into healthy meals.Footnote 3 With the guidance of the supporting organizations (Avanade and Accenture), The Felix Project went through a DT to facilitate its services. Initially, the NPO only requested a mobile application to automize its route planning process and digitize the activities of the volunteering drivers. More importantly, through collaborative workshops, the supporting organizations found that the existing CRM system needed to be upgraded and new data handling procedures should be in place to meet the NPO’s changing needs of impact visualization.

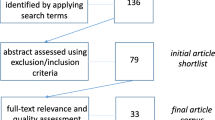

Coherently with the case study-grounded theory methodology (Halaweh et al., 2008), we reviewed existing literature (Yin, 2009) to define an initial set of interpretative categories (Eisenhardt, 1989) around which the interview protocol was designed (Mitchell, 2014). Essentially, these were used to divide the interview guide into subtopics, each with several questions that were relevant to the participant’s role in the collaboration (see Table 1). This resulted in two interview guides; one was used for the participants of the supporting organizations, another was used for the participants from The Felix Project. The study commenced with theoretical sampling which is a form of purposeful sampling that concurrently collects and analyzes data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Ligita et al., 2019) through various stages of coding, jointly undertaken with memoing and constant comparative analysis which is an iterative approach until theoretical saturation was reached (Chun Tie et al., 2019). This is the point where obtaining extra data did not add any new relevant information to the research (Thomson, 2011) and therefore guided the researcher to the appropriate sample size (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Data Collection

Theoretical saturation was achieved at a total of 9 respondents who had actively participated in and taken on a different role during the DT of The Felix Project. After each interview was conducted, it was being analyzed through the formation of codes and categories that emerged from the data to understand what information to collect next and which interview was needed to get this (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The process continued until obtaining extra data did not produce any new nor relevant insights (Thomson, 2011). The data was collected at a single point in time through semi-structured interviews, as both grounded theory and case study take interviews as the main data collection technique (Strauss & Corbin, 1990; Yin, 2009). The interviews, due to the pandemic situation, were conducted online through a videoconferencing tool and lasted between 40 to 50 min each. Interviewees were informed about their privacy rights and gave their consent to record the interview. As participants could express their experience by language, it effectively revealed in-depth details (Black, 2006) and allowed for a full range of visual and verbal exchange (Salmons, 2012).

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed and uploaded in NVivo, which is a software that allows unstructured data like text, audio, or video to be analyzed. To interpret these, six steps of Tracy (2013) were followed: (i) raw data were gathered, stored, and prepared to handle the filing, naming, and de-identification of the respondents, (ii) open codes were created by taking small chunks of text and labeling it with any code that represents a certain topic or theme (e.g., response, feedback, team) (Blair, 2015), (iii) a codebook was created to provide a clear overview of the definition of the codes and the number of times it occurred, (iv) axial codes were created by relating open coded data to each other and combining it into group codes (e.g., collaboration, flexibility) (Scott & Medaugh, 2017), (v) the first four steps were repeated for each transcript, (vi) selective codes were created by linking the group codes to each other to create conceptual categories (e.g., willingness to change: agility, leadership and entrepreneurship) (Bernard, 2002).

During the interviews, memo writing took place to detail out the thought process of coding by creating new codes, collapsing codes, merging codes, separating codes, and identifying relationships between the codes (Chun Tie et al., 2019). These served as an explicit means to support the coding process and evolve a series of relationships into a theoretical framework (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Findings

Willingness to Change: Agility, Leadership and Entrepreneurship

The interviews uncovered the importance of creating a sense of willingness to change by embracing an agile approach with regard to change management, building a shared ambition toward DT in an NPO which is supported by the leadership, and promoting an entrepreneurial spirit toward the achievement of this commitment. Because NPOs generally operate in a relatively rigid environment when it comes to executing major transformations, taking agility as part of changing the way of working in such settings is found to be suitable to continuously feed members’ engagement and participation. Likewise, the involvement of top management toward the change and the perception of reaching the goal of successful DT in an NPO comparable to performing as a business reaching targets is suggested to influence the members of the NPO in the desired direction in a pragmatic way.

NPOs should promote a proactive attitude toward change through agility by encouraging its people to prioritize, quickly react to, and engage with the supporting organizations. Key components of being agile such as flexibility, coordination, accuracy and speed, help members of the NPO to continuously verbalize their needs and quickly respond to the advancements of the supporting organizations at a constant pace. As Respondent E [The Felix Project] argues: We didn’t spend months documenting requirements and writing complex documents. It was very iterative, very fast moving. We would discuss requirements, the team would go off to develop it, and then a day or two days later we would be looking at it again. Similarly, Respondent B [Avanade] argues: We were able to tell them what we were facing, and they would say all right let’s meet for half an hour, let’s decide and get it through. This shows that the adoption of an agile approach may give members of the NPO the feeling of being listened to, taken onboard, and consulted for input along the DT, which could result in less resistance and more willingness to change.

Furthermore, the experience at The Felix Project supports the idea that DT should be driven from and owned by top management. The CEO at the time was equally committed to technology and the benefits of technology, relevant to our mission: not technology for the sake of it, but technology that would enable us to do more. The senior leadership has to understand this and support the purpose of the technological change—Respondent D [The Felix Project]. Here, the emphasis is on leaders to proactively engage in the management and communication of innovation to reassure the NPO’s members about potential risks and motivate them to undertake an active role in the process of change. More importantly, it shows that senior leadership is fundamental to guide the members of the NPO to embrace the DT by creating a passion among members of the NPO to actively seek opportunities to change and by being transparent about the process to accentuate the purpose and relevance of the DT to the objective of the NPO.

In the situation of The Felix Project, it is also suggested that being entrepreneurial can facilitate successful DT. Specifically, this was defined by being open to innovation, embracing risks, being dynamic in the way of working, and being collaborative while striving for value creation. Respondent E [The Felix Project] states: Generally, the culture within Felix is very entrepreneurial, very much feeling that we are on a real mission with a very can-do attitude. Nothing seems impossible. Respondent A [Avanade] recognized this: They were very collaborative and open to explore new ways of working…. They were prepared to come out of their comfort zone…. If they could see there might be a better way to quickly realize their vision, then they’d be entirely on board. The Felix Project’s members developed a business-like mindset that might have helped the NPO to renovate and strengthen the sense of belongingness and the common purpose of the DT which is also observed by Respondent B [Avanade]: The feedback was really strong…. They were so eager to do the testing…. All of that came because they had the desire, the ambition to be better.

Co-Creation: Technology with and for End-Users

The human factor is experienced to be a key component in The Felix Project. Involvement within such NPOs often cannot be reduced to self-interest, but to emotions and sentiments of belonging to the so-called human sphere. The introduction of innovative managerial practices developed for the for-profit sector may impact the human touch that pervades those organizations. Therefore, implementing methods that ensure that innovation is not developed only for the sake of efficiency, but also for the people and the community, is ought to be crucial for NPOs. This is noticed by Respondent H [The Felix Project]: The sky is the limit with how we run our warehouses, for example with robotics or data technology, all sort of things like that…. We just have to remember the people at the very end of it…. For any tech improvement, we have to be aware that a motivator for a volunteer is that they get to choose themselves how to give what we have to people in the best way…. With any new technology, people can only handle a certain amount of change.

In this respect, the adoption of the co-creation methodology in The Felix Project seems to have succeeded in enhancing the transfer of the human touch in the technology. Employees and volunteers have been involved in a ‘day in the life’ workshop. This is a methodology, based on participant observation, to extract the tacit knowledge embedded in the daily routines and the relationship between people. It is used to co-construct technologies that are user-friendly and in line with targeting users’ know-how and competencies. The interactive nature of those workshops also allows participants to get trained and develop mental representations of the emerging technological context. By working together, it became clear that the DT allowed the tools, that the staff and volunteers were using to carry out their services, to be digitally upgraded in a way that provides seamless operations and supported processes to be made quicker, more accurate, and more worthwhile, as Respondent E [The Felix Project] agrees: It took away some painful parts of the process in the operations.

Simultaneously, the co-creation methodology required a close work relationship between the NPO and the supporting organizations, and a collaborative attitude among staff and volunteers to elicit deeper needs. In this way, purposeful ideas were being shared and feedback was being used to improve together. Here, deep involvement of the end-users is believed to result in an optimal fit between the digital technologies and the operational activities of the NPO, leading to a new, enhanced form of value. From the beginning they were involved. They helped us ideate and brainstorm and design the UI—Respondent C [Accenture]. Moreover, involving staff and volunteers in the DT enabled the processes to be more intuitive, user-friendly and less complicated, which was crucial seeing the diverse workforce in the NPO. We do some just-in-time training to enable the volunteers to get used to the systems…. But I would say it is a bigger problem in our environment than you would find in a more traditional environment with paid employees…. It is harder for volunteers…. So, the systems need to be more intuitive, more consumer styled than you can get away with in a normal commercial environment—Respondent E [The Felix Project].

Create a Data-Driven Learning Culture

Within The Felix Project it was discovered that building a data-driven learning culture was essential to understand the effects of the technology and eventually accept and advocate the DT. The interviews highlighted that once members of the NPO were aware of the impact of consistent data collection, real-time data analysis, and doing this with the proper data for the appropriate purposes using either qualitative or quantitative methodologies, the staff and volunteers would be more inspired and passionate about making the DT process a success. Every part of it has really started to appreciate the value of data, how to use that data, and has become more demanding in terms of its reporting and seeing dashboards—Respondent E [The Felix Project].

Respondent C [Accenture] also shows how the workshop brought to light that a clear data governance structure regarding their CRM platform was much needed, rather than only a simple routing app, to accomplish their common mission: We built a day in the life, which was the most critical thing because that is when the Avanade folks realized that the depot manager is using this constellation of low-quality software since they had some random CRM that they were using online…. It ended up being the most useful thing in the entire project, because if we would not have done that, we may have never discovered that: Yes, we will build a mobile app, but the bigger problem they have is this whole CRM spaghetti. Their ambition to scale to 100 million meals by 2024 would be completely hampered by this—Respondent C [Accenture].

To build a data-driven learning culture within the organization, it is required for data collection to have a clear purpose and to have a consistent, standard way of working. Especially for the end-users who will eventually provide the data by manually putting it into the system. Respondent F [The Felix Project]: It puts consistency across the depots about how that data was gathered and what data was gathered. It also gave us the ability to just have information on our fingertips. Likewise, Respondent G [The Felix Project] explains about significance of accurate data storage: Everything links to one place so that there is no disconnect between everything else that we do…. It is a positive impact to the operations having one central point, so there is no confusion…. It is now on the same platform, whereas various other tools have been built previously, and the value of having access to historical data: If you think about small things like all the history who has done what at what time, everyone can access the same information at any given time from anywhere as long as they have the links.

More importantly, a data-driven learning culture shows its importance when the data can produce meaningful information as it is being used to visualize the impact that is being made by the NPO: We built all these great dashboards that would read the data and display it. Instead of having a monthly report that they (the volunteers) all hung over and study, they now have real-time dashboards, always up to date—Respondent C [Accenture]. In this way, it will motivate the volunteers to stay committed to the NPO’s vision and devote their time to volunteer. The value of purposeful data usage will also be uncovered when it shows its potential to help an NPO improve its services. It allows people with influential positions in the NPO to look at their mission and prioritize, align objectives to their strategy, and make better decisions by using facts derived by the collected data. Respondent D [The Felix Project] mentions: We gave the power of data-led decision making to frontline managers and frontline staff. That is really powerful because that cultural change is very difficult to achieve.

Above all, to meet the needs of the community it serves, NPOs need to have the resources to grow and scale up. For this, funding is needed, which can be attracted when NPOs can convince businesses and individuals about the impact it creates for society. As Respondent F [The Felix Project] puts it: We are 100% reliant on people’s donations and we need to be able to make decisions based on facts rather than anecdotally, and being data driven allows us to do that. We can be a lot more accountable and that’s extremely important for a charity. In sum, being open to the collection, storage, and usage of data and creating a data-driven organizational culture is very important for an NPO since it will enable their operations in multiple ways.

Discussion

The goal of this paper was to explore the implementation of a DT strategy in an NPO operating in the field of food charity in London. To this end, to root our exploration on more solid ground, we took the stance of the literature on NPOs and strategy, and we conducted an in-depth single case study applying the grounded theory methodology based on multiple interviews with participants in the project of DT. In this respect, we believe our analysis has produced significant contributions to existing literature.

First, we highlight that cultivating a common willingness to change within an NPO is crucial to make the DT a success. In this respect, our study highlights three matters. First, the importance of adopting agile management to stimulate engagement and participation and build a common sense of purpose in NPOs. Second, the importance of including the right leaders that reinforce the DT and include people at the top who have leadership skills and capabilities to positively assist the DT. The attitude and support from the head of the organization matters the most when it comes to implementing such an organizational change (Frankiewicz & Chamorro-Premuzic, 2020). Third, having an entrepreneurial spirit changes the risk-averse attitude NPO’s generally seem to have (Hull & Lio, 2006), stimulating new value creation.

H1

Adopting an agile approach helps NPOs’ members to renovate their common purpose and sense of belonging through DT.

H2

The capacity of the leadership to support a positive attitude toward change among volunteers is critical to strengthening DT in an NPO.

H3

Fostering an entrepreneurial culture within NPOs facilitates DT, as it encourages members to be open to innovation, more willing to take risks, and more collaborative.

Secondly, we highlight the impact of the human factor on implementing DT in NPOs. This finding also partially aligns with the results of Nahrkhalaji et al. (2018), which identified a lack of technical expertise as a significant constraint during DT in NPOs. However, our study emphasizes an additional dimension, namely the importance of considering the motivations that drive people to participate in NPOs, which can be influenced by the adoption of digital technologies. As expressed by Respondent H [The Felix Project], NPO managers should bear in mind that there are people at the end of it. When introducing technological improvements, managers should be mindful of the motivations that drive individuals to work in NPOs. This is particularly relevant for volunteers, who desire autonomy in determining the most effective ways to contribute their skills and resources to the cause. As suggested by Chui and Chan (2019), digital technologies can enhance NPOs’ ability to recruit volunteers, expand and diversify the volunteer pool, attract professionals, and reduce administrative costs associated with volunteer management. However, technology may hinder willingness to participate if it infringes upon volunteers’ freedom to interpret their roles. Therefore, a DT strategy solely focused on maximizing process efficiency without considering the social significance it holds for individuals performing the work can disrupt engagement in NPOs. Our findings confirm the importance of fostering a supportive environment characterized by mutual care and a sense of belonging, which can elicit collective knowledge within the organization and ensure a human-centered approach to technology. Furthermore, we found that co-creation methodologies can contribute to establishing a positive environment for the development and execution of DT. Specifically, cultivating collaborative and co-creative relationships between staff, volunteers, and supporting organizations can mitigate conflicts arising from the diverse nature of an NPO’s workforce (Hull & Lio, 2006).

H4

DT in NPOs should be led with care to influence people’s motivation to participate and be a member of an NPO.

H5

The adoption of co-creation approaches helps to build up a friendly environment based on mutual care, which is required for DT to succeed.

Third, creating a data-driven learning culture is a relatively new phenomenon in NPOs and builds on existing evidence of Lu et al. (2019), as their research mostly deals with the use of data in NPOs for mission drift avoidance, decision making, and fundraising. First, the interviews found that actively communicating the added value of NPOs helps to avoid a lack of focus as it enables staff and volunteers to discover the difference that is being made because of their hard work. Consequently, this will motivate the members of the NPO and will remind them about the goal they are trying to reach. Second, the interviews highlighted the relevance of data regarding the NPO’s decision-making strategy. It allows the people with influential positions to make better decisions based on the specific circumstances and therefore makes the NPO more accountable. This data-driven decision making adds to the sustainability of the NPO (West, 2019). Third, it is also shown that data is necessary to share the influence NPOs are making based on facts, rather than anecdotes. In this way, the impact of such organizations will be more credible, which is important to receive funds, as NPOs are highly reliant on donations (Lee & Shon, 2018).

H6

The emergence of a data-driven learning culture supports DT as it provides volunteers with better information on the meaning of their contribution to the NPO’s mission.

H7

The emergence of a data-driven learning culture reinforces DT as it strengthens the efficiency and effectiveness with which NPOs interpret their mission through better decision making.

Since this exploratory study is a preliminary research on the relatively new topic of DT in NPOs, some limitations have been found. First, the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic could influence the perception of the role of DT on The Felix Project’s operations. On the one hand, the decrease in volunteers resulted in less food being collected and fewer meals being delivered, which means that the effect of DT on the number of meals delivered could have been underestimated. On the other hand, the decrease in volunteers resulted in fewer feedback loops and less resistance from the end-users, which means that the effect of DT might have been overestimated.

Furthermore, since this research has adopted a single case study approach, it has focused its results on the context and circumstances of one specific NPO. This might have limited the outcome in several ways. First, The Felix Project is an NPO based in the United Kingdom that operates within and around London. The fact that this NPO is functioning in a metropolis could have required a specific setting which could have influenced the outcome. For instance, the location of the NPO might have induced highly skilled, knowledgeable individuals to volunteer. This could have altered the diversity that is generally present in an NPO’s workforce. Second, the DT was prompted in a developed country, which could have been very different in a developing country, given the level of knowledge and the availability of resources. Third, The Felix Project is a specific NPO that is focused on redistributing excess food to provide meals to the ones that experience food poverty. It is active in the food bank industry, which only helps to reach one part of sustainability. This shows that the results of this single case study are limited and cannot be represented in every NPO aiming for every type of sustainability achievement.

Thus, future research should explore this study in crisis-free times to include as many volunteers in the process and receive as many responses as possible to get a better understanding of the effect of the DT. Also, the results of this research are limited by the fact that a single case study approach is adopted where the London-based NPO, The Felix Project, is inspected. To get a broader perspective of the certain factors that can influence the impact of DT on the efficiency and effectiveness of sustainability achievement in NPOs, more cases should be reviewed.

Conclusion

The objective of this paper was to investigate the process of DT in sustainability driven NPOs. To this end, we implemented a single case study-grounded theory methodology around The Felix Project, a charity operating in the food redistribution sector in London. Our interpretation has been grounded on strategy and NPO literature, which focuses on NPOs adopting managerial practices developed in the for-profit sector. More specifically, we focus on the literature studying innovation in NPOs.

From this perspective, our study has produced several contributions as it has uncovered some initial insights into how DT is adopted in NPOs. First, it highlights the key role of leadership and entrepreneurship in enabling change also in NPOs as a setting involving a larger and diversified number of stakeholders imbued with social and ethical motivations to participate. Second, it stresses the importance of agile management and lean methodology to renovate the common purpose to reach the NPO’s mission, especially highlighting the importance of considering the human sphere when implementing DT in the NPO’s setting to prevent possible displacement of altruistic motivations and self-determination when taking part in an NPO. Finally, we emphasize the need of cultivating a data-driven learning culture. However, not only with aim of strengthening optimization and continuous improvement, but also and mainly to enhance internal and external accountability.

This study makes only the first step in the direction of understating DT in NPOs as a key driver in our running after SDGs. Further work is required as we identified some possible future research directions to extend the value of our study. We hope those opportunities will be soon seized, and this work may become a small step toward a sustainable future.

Notes

The propensity to apply those methodologies may change from company to company and from industry to industry. It is quite common among companies operating in innovation-driven industries, such as industries in which digital technologies are a source of competitive advantage. It is less frequent in more traditional sectors. However, also in those sectors, there is a growing number of companies is applying these methodologies, such as in the agriculture industry. Furthermore, the propensity to adopt those technologies is lower in public institutions and NPOs. Although, even in those sectors the propensity is also increasing.

Ibidem.

References

Aboramadan, M., Hamid, Z., Kundi, Y. M., & El Hamalawi, E. (2022). The effect of servant leadership on employees’ extra-role behaviors in NPOs: The role of work engagement. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 33(1), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21505

Andersson, F. O., & Self, W. (2015). The social-entrepreneurship advantage: An experimental study of social entrepreneurship and perceptions of nonprofit effectiveness. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(6), 2718–2732. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9543-1

Bernard, R. H. (2002). Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods (3rd ed.). AltaMira Press.

Black, I. (2006). The presentation of interpretivist research. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 9(4), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750610689069

Blair, E. (2015). A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 6(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.2458/v6i1.18772

Brandsen, T., Van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9–10), 749–765. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200067320

Cabral, S., Mahoney, J. T., McGahan, A. M., & Potoski, M. (2019). Value creation and value appropriation in public and nonprofit organizations. Strategic Management Journal, 40(4), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3008

Centobelli, P., Cerchione, R., & Ertz, M. (2020). Agile supply chain management: Where did it come from and where will it go in the era of digital transformation? Industrial Marketing Management, 90, 324–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.07.011

Chui, C. H. K., & Chan, C. H. (2019). The role of technology in reconfiguring volunteer management in nonprofits in Hong Kong: Benefits and discontents. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 30(1), 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21369

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. Sage Open Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312118822927

Do Adro, F., & Fernandes, C. (2021). Social entrepreneurship and social innovation: Looking inside the box and moving out of it. Innovation: the European Journal of Social Science Research, 35(4), 704–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2020.1870441

Do Adro, F. J. N., & Leitão, J. C. C. (2020). Leadership and organizational innovation in the third sector: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 4(2), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2020.04.001

Do Adro, F., Fernandes, C. I., & Veiga, P. M. (2022). The impact of innovation management on the performance of NPOs: Applying the Tidd and Bessant model (2009). Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(4), 577–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21501

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

Euske, K. J. (2003). Public, private, non-profit: Everybody is unique? Measuring Business Excellence, 7(4), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/13683040310509250

Evers, A. (2005). Mixed welfare systems and hybrid organizations: Changes in the governance and provision of social services. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9–10), 737–748. https://doi.org/10.1081/PAD-200067318

Evers, A. (2020). Third sector hybrid organisations: Two different approaches. In D. Billis & C. Rochester (Eds.), Handbook on hybrid organisations (p. 294). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Frankiewicz, B., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2020). Digital transformation is about talent, not technology. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from Digital Transformation Is About Talent, Not Technology (hbr.org).

George, G., Merrill, R. K., & Schillebeeckx, S. J. (2021). Digital sustainability and entrepreneurship: How digital innovations are helping tackle climate change and sustainable development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 45(5), 999–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719899425

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Pub. Co.

Halaweh, M., Fidler, C., & McRobb, S. (2008). Integrating the grounded theory method and case study research methodology within is research: A possible ‘road map’. ICIS 2008 Proceedings, 165.

Hanelt, A., Bohnsack, R., Marz, D., & AntunesMarante, C. (2021). A systematic review of the literature on digital transformation: Insights and implications for strategy and organizational change. Journal of Management Studies, 58(5), 1159–1197. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12639

Hull, C. E., & Lio, B. H. (2006). Innovation in non-profit and for-profit organizations: Visionary, strategic, and financial considerations. Journal of Change Management, 6(1), 53–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010500523418

Jaskyte, K. (2015). Board of directors and innovation in nonprofit organizations model: Preliminary evidence from nonprofit organizations in developing countries. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26(5), 1920–1943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9505-7

Laurett, R., & Ferreira, J. J. (2018). Strategy in nonprofit organisations: A systematic literature review and agenda for future research. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(5), 881–897. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-017-9933-2

Lee, Y. J., & Shon, J. (2018). What affects the strategic priority of fundraising? A longitudinal study of art, culture and humanity organizations’ fundraising expenses in the USA. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(5), 951–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-9982-1

Ligita, T., Harvey, N., Wicking, K., Nurjannah, I., & Francis, K. (2019). A practical example of using theoretical sampling throughout a grounded theory study: A methodological paper. Qualitative Research Journal, 20(1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/QRJ-07-2019-0059

Lu, J., Lin, W., & Wang, Q. (2019). Does a more diversified revenue structure lead to greater financial capacity and less vulnerability in nonprofit organizations? A bibliometric and meta-analysis. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(3), 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-019-00093-9

Maier, F., Meyer, M., & Steinbereithner, M. (2016). Nonprofit organizations becoming business-like: A systematic review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014561796

Mitchell, D. (2014). Advancing grounded theory: Using theoretical frameworks within grounded theory studies. The Qualitative Report, 19(36), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2014.1014

Moi, L., & Cabiddu, F. (2021). Leading digital transformation through an agile marketing capability: The case of Spotahome. Journal of Management and Governance, 25(4), 1145–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09534-w

Muench, S., Stoermer, E., Jensen, K., Asikainen, T., Salvi, M., & Scapolo, F. (2022). Towards a green and digital future. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2760/977331

Nahrkhalaji, S. S., Shafiee, S., Shafiee, M., & Hvam, L. (2018). Challenges of digital transformation: the case of the non-profit sector. In 2018 IEEE international conference on industrial engineering and engineering management (IEEM) (pp. 1245–1249). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEM.2018.8607762

Oliveira, M., Sousa, M., Silva, R., & Santos, T. (2021). Strategy and human resources management in non-profit organizations: Its interaction with open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 75.

Phillips, W., Lee, H., Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., & Jamer, P. (2015). Social innovation and social entrepreneurship: A systematic review. Group and Organization Management, 40(3), 428–461. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601114560063

Sakthi Nagaraj, T., & Jeyapaul, R. (2021). An empirical investigation on association between human factors, ergonomics and lean manufacturing. Production Planning & Control, 32(16), 1337–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1810815

Salmons, J. (2012). Cases in Online Interview Research. Sage Publications.

Sanzo, M. J., Álvarez, L. I., Rey, M., & García, N. (2015). Business–nonprofit partnerships: Do their effects extend beyond the charitable donor-recipIENT Model? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(2), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013517770

Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2007). Research methods. Business Students 4th edition Pearson Education Limited.

Scott, C., & Medaugh, M. (2017). Axial coding. The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, 10, 9781118901731. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0012

Sharma, V., Raut, R. D., Mangla, S. K., Narkhede, B. E., Luthra, S., & Gokhale, R. (2021). A systematic literature review to integrate lean, agile, resilient, green and sustainable paradigms in the supply chain management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 1191–1212. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2679

Silverman, D. (2014). Interpreting qualitative data. Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research techniques. Sage Publications.

Tabrizi, B., Lam, E., Girard, K., & Irvin, V. (2019). Digital transformation is not about technology. Harvard Business Review, 13(3), 1–6. Retrieved from Digital Transformation Is Not About Technology (hbr.org).

Taylor, K. (2015). Learning from the co-operative institutional model: How to enhance organizational robustness of third sector organizations with more pluralistic forms of governance. Administrative Sciences, 5(3), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci5030148

Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

Thomson, S. B. (2011). Sample size and grounded theory. Journal of Administration and Governance, 5(1), 45–52.

Tracy, S. J. (2013). Qualitative research methods. Wiley-Blackwell.

Upadhyay, A., Mukhuty, S., Kumari, S., Garza-Reyes, J. A., & Shukla, V. (2022). A review of lean and agile management in humanitarian supply chains: Analysing the pre-disaster and post-disaster phases and future directions. Production Planning and Control, 33(6–7), 641–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537287.2020.1834133

Van der Have, R. P., & Rubalcaba, L. (2016). Social innovation research: An emerging area of innovation studies? Research Policy, 45(9), 1923–1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2016.06.010

West, A. (2019). Data-driven decision making for not-for-profit organizations. The CPA Journal, 89(4), 10–12. Retrieved from Data-Driven Decision Making for Not-for-Profit Organizations (cpajournal).

Woo, D., Actis, K., & Fu, J. S. (2022). Nonprofits’ external stakeholder engagement and collaboration for innovation: A typology and comparative analysis. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 33(4), 711–733. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21547

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications.

Zahra, S. A., Gedajlovic, E., Neubaum, D. O., & Shulman, J. M. (2009). A typology of social entrepreneurs: Motives, search processes and ethical challenges. Journal of Business Venturing, 24(5), 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Milano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Cindy Li Ken Jong, while collecting the data for this paper, was working as an intern at Avanade, one of the supporting companies involved in the project. She did not contribute to the project in any way as it was already finished when she started to collect data. Afterwards, she continued to work at Avanade and is currently still employed there.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jong, C.L.K., Ganzaroli, A. Managing Digital Transformation for Social Good in Non-Profit Organizations: The Case of The Felix Project Zeroing Hunger in London. Voluntas (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00597-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00597-5