Abstract

Volunteering involves caring for the outcomes of others and typically long-term orientation so that one can achieve goals that are not always clearly visible in the short term. As with any activity, volunteering attracts people of different social value orientations—some rather individualistic, some rather altruistic. The aim of the study was to find out whether the future time perspective, which promotes thinking about future goals and planning, is linked to volunteers' declarations of the probability of them continuing volunteering in a month, year, and three years and whether this link is moderated by social value orientation. An online questionnaire-based study was performed on a sample of 245 volunteers. The results indicated that the higher the social value orientation, the greater the predicted probability of continuing volunteering. Future time perspective was related to the predicted probability of continuing volunteering in all investigated time horizons only when volunteers had a more individualistic than altruistic social value orientation. Younger age and longer experience with volunteering were also linked to the predicted probability of continuing volunteering in a year and three years (but not in one month). The results show the importance of social value orientation and future time perspective for more individualistic volunteers in their willingness to volunteer further. The study has practical implications for organizations' management, who should consider developing cooperation skills in their volunteers. For competitive volunteers, they may also highlight how challenges could make an impact in the future so that they intend to remain active.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Volunteering is an activity aimed at helping people, groups, or organizations and encompasses devotion of time out of free will (Omoto & Packard, 2016; Wilson, 2000). No friendship, family, or professional relations should be present between the volunteer and the beneficiary so that no previous obligations to help exist (Snyder & Omoto, 2007). Many organizations rely on volunteers to successfully pursue their mission (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al., 2015). A significant and current problem is retaining volunteers and preventing quitting the activity (Dwiggins-Beeler et al., 2011), especially among young people (Veludo-de-Oliveira et al., 2015).

Voluntary action is typically associated with attentiveness to others, their needs, and outcomes. Moreover, young volunteers tend to prefer to participate in such volunteering activities in which they see that their engagement improves the quality of life of others. They introduce positive changes thanks to their work, and where they can obtain some benefits for engagement (Shields, 2009).

It is congruent with the functional theory of volunteering (Clary et al., 1998), according to which this activity may be performed out of various motives. The care for others or the desire to show altruistic values may be one of many such motives. In some cases, volunteering can attract more individualistic than altruistic people, for example, when motivated to enhance their careers, learn new skills, or elevate a positive mood. Being ready to volunteer for longer may be more manageable for altruistically oriented people. It might be due to better internalization and congruence of this role with their values and identity. For individualists, however, the intention to remain active might need to be stronger, as their motivation could be only to get the needed benefits. What could help them in deciding to stay? We hypothesize that this factor could be the consideration of the temporal aspect of engagement—future time perspective—which supports planning and long-term orientation, as well as being able to sacrifice in the present to achieve future goals.

The aim of the study is to test whether future time perspective links to the predicted probability of further volunteering (by the volunteers themselves) in three time horizons: one month (short), one year (long), and three years (very long). The study will test whether social value orientation (greater competitiveness/individualism versus greater prosociality/altruism) moderates this relationship. Below, we present a literature review and the hypotheses with their justification.

Literature Review

Social and Temporal Aspects of Prosocial Behavior

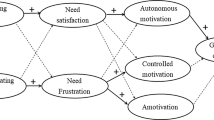

According to researchers of prosociality, the decision to undertake prosocial behaviors relies on consideration of two aspects by the actors: social (conflict between acting for own interests versus collective interests) and temporal (conflict between acting for short- and long-term interests; Joireman, 2005; Joireman et al., 2001; Milfont & Gouveia, 2006). Social and temporal facets have been considered in studies on various prosocial outcomes (Arnocky et al., 2014; Joireman et al., 2001; Maki et al., 2016). Social value orientation is often used to operationalize the social aspect, which refers to caring for others' outcomes in social interactions (Murphy et al., 2011). For the temporal aspect, in volunteering studies, attitudes toward the future are used as an operationalization (e.g., consideration of future consequences; Joireman et al., 2001; and in newer studies, future time perspective; Maki et al., 2016). It is because volunteering involves planning, setting goals, striving for long-term goals, and believing that a change can occur in the future (Maki et al., 2016; Simons et al., 2004). In the subsequent sections, we will elaborate more on these aspects, stating specific hypotheses.

Volunteering Among Young Adults

In young adulthood, people can consolidate their self-esteem and prosocial attitude (Crocetti et al., 2016; Padilla-Walker & Van der Graaf, 2023). Social engagement, e.g., volunteering, can support young people in gaining professional experience and developing personally (Flanagan & Levine, 2010; Marta et al., 2006; Nowakowska, 2020a). Even though young adults typically can engage emotionally in the actions they undertake and invest energy in coping with adversities ("virtue of fidelity," Erikson & Erikson, 1998), not every one of them uses it or learns persistence in decisions made throughout the adulthood period. Nowadays, due to many social changes, there is a growing social allowance toward young adults to elongate the time of stabilization of their own lives and remain in the moratorium stage, which is characteristic of adolescents and relies on exploration and seeking their own identity (Côté, 2006; Padilla-Walker & Van der Graaf, 2023). It may negatively affect the young adults’ readiness to remain active in their obligations, including volunteering. The younger the volunteers, the lower their loyalty to the causes and institutions for which they work (Hustinx, 2001; Rehberg, 2005; Shields, 2009). At the same time, young people are essential targets and elements of the volunteering system (Freeman, 1997), and retaining them seems crucial.

Considering the Social Aspect of Prosocial Decisions—Social Value Orientation

As stated above, people need to consider social (mine versus others’ well-being) and temporal (present versus future) aspects when making prosocial decisions (Joireman et al., 2001). An individual difference that is responsible for social considerations is social value orientation. It describes how much a person cares for others in social interactions (Murphy et al., 2011; Van Lange et al., 2007). Social orientations are classified categorically from fully competitive to entirely altruistic (McClintock, 1978; Murphy & Ackermann, 2014). They are a form of a personal norm that obliges one to behave to maximize one's benefits (when the social value orientation is more competitive) or the benefits of another person (when it is more altruistic; Joireman et al., 2001; Messick & McClintock, 1968). Social value orientations are often measured using games based on resource allocation between oneself and others. These games are based on unilateral decisions—the participants decide about the amount of money or other resources, e.g., points they receive and what other receives (Murphy et al., 2011).

According to Gilbert et al. (2017), altruism is a component of the internal need to volunteer. More altruistic social value orientation predicts charitable donations and being a voluntary participant in research (McClintock et al., 1989). Moreover, in research based on the general population, the perspective of improving social justice—which might be interpreted as a component of altruistic social value orientation—through volunteering was one of the most critical aspects of the willingness to start volunteering engagement (Jiranek et al., 2013).

Following the theoretical foundations and empirical evidence, we hypothesize that in the current study:

H1

The higher the social value orientation (the more altruistic it is), the higher the volunteering intention, regardless of the time horizon for which it is declared.

Considering the Temporal Aspect of Prosocial Decisions—Future Time Perspective

The temporal aspect of prosocial decisions involves considering the short- (present) and long-term (future) consequences of actions (Joireman et al., 2001). Moreover, according to the social norm activation model (Schwartz, 1970), individuals act according to the social norms when they believe in their agency and the future consequences of their actions. The belief in the consequences of one's own actions is characteristic of the future time perspective (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). Thus, the future time perspective could help see the long-term benefits for self and others in volunteering.

Time perspectives (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999) are the tendency to assign experiences to the temporal frameworks of the past, present, or future. When habitually utilized, they become relatively stable traits, regarding which we can observe individual differences (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999, 2008). Traditionally, time perspectives are distinguished into past negative (negative attitude toward own past), past positive (nostalgic, positive attitude toward one's past), present fatalistic (the conviction that the present cannot be influenced and one should give up to the events), present hedonistic (connected to the pleasure orientation and seeking sensation in the present) and future (concentration on what is to come, the tendency to plan and work to achieve the desired effect regardless of the cost; Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999).

The future time perspective is linked to setting, monitoring, and achieving goals (Baird et al., 2021). Its role in prosocial behaviors is presented in a twofold way. On the one hand, Zimbardo and Boyd (2008) argue that future-oriented individuals have a lower tendency to help others, given that they are too self-focused. According to them, prosociality requires at least some embeddedness in the present to notice the needs of others in the environment. However, empirical data suggest that future orientation may promote prosocial behaviors thanks to the ability to sacrifice short-term benefits to achieve success and to wait for the effects of own actions. For volunteering, such waiting abilities can help sustain action, given that the effects could not be visible immediately. It applies to the effects of help for the beneficiaries and the potential benefits for self-development, such as gaining knowledge or skills. Empirical data support this notion, as future time perspective can promote helping others to introduce changes in the well-being of others or, more generally, to positively influence society and establish reciprocity norms (Chernyak-Hai & Halabi, 2018; Maki et al., 2016). There are also correlations between future orientation and hours spent on volunteering (Metzger et al., 2018), as well as motivational strength, satisfaction from engagement, and readiness to start extra engagement (Maki et al., 2016).

Considering these insights, it could be hypothesized that in the context of the intention to continue volunteering, the future time perspective could be (1) especially relevant for individualists, as it promotes considering the positive effects for self-development (Zimbardo & Boyd, 2008). Presumably, it could promote engagement in volunteering to get competences or experiences; (2) in the case of individualists, it might promote volunteering intentions, as a higher future time perspective relates to persistence in realizing long-term goals. Individualists have a weaker inner need to contribute to others' well-being (compared to altruists) and need another factor to remain involved in prolonged prosocial action. They need to see the long-term benefits of their actions, and the ability to anticipate future benefits may be critical in their desire to sustain the activity. That is why we hypothesize that:

H2

Future time perspective moderates the role of social value orientation to intentions to remain an active volunteer so that the relationship between future time perspective and intention to remain a volunteer is stronger the more self-oriented (individualistic) the volunteer is.

Demographics and Predicted Probability of Future Volunteering

In our study, we will also control for the age of the volunteers, given that the older the people, the more personal and professional obligations may hinder them from volunteering (Freeman, 1997). We also will control for gender, as traditional, gendered division of labor and gender equality issues shape the volunteering patterns in men and women differently (Bellido et al., 2021; Taniguchi, 2006). We will also see whether the length of experience with volunteering affects our patterns of results, as the longer the experience, the more internalized the role is (Finkelstein et al., 2005).

We will test models for the predicted probability of further volunteering in one month, one year, and three years to see whether the effects differ when the declarations to volunteer in shorter or longer time horizons are considered.

Novelty of the Study

The study expands the existing body of literature regarding the social and temporal aspects of engagement in prosocial behaviors (e.g., Joireman et al., 2001; Maki et al., 2016; Milfont & Gouveia, 2006). It also proposes a novel model involving a moderating effect of future time perspective in the relationship between social value orientation and volunteering intentions, integrating the data from previous research. Despite the theoretical relations between social value orientation and prosocial actions such as volunteering, few studies have been conducted to date on the topic. Contrary to other studies, ours is focused on a specific group of young adult volunteers, who are crucial in their retention within volunteering programs (Shields, 2009). Understanding the examined phenomenon could help organizations better tailor their activities to retain volunteers based on their personal traits (attitudes toward others—competitive versus altruistic, and considerations of the future consequences of their own actions).

Method

Participants

Two hundred forty-five people aged 18–35 (M = 23.93; SD = 4.61), 199 females (81.2%) and 43 males (17.6%), and 3 (1.2%), who declared other gender or refused to answer, took part in the study. Fifty (20.4%) participants lived in a village, 100 (40.8%) in a town with less than 100,000 inhabitants, 50 (20.4%) in a town with 100,001–499,999 inhabitants, and 45 (18.4%) with more than 500,000 inhabitants. Thirteen (5.3%) people had primary school education, 108 (44.1%) finished high school, one person (0.4%) vocational school, 59 (24.1%) had a Bachelor's degree, 56 (22.9%) Master's degree, 4 (1.6%) had a Ph.D. degree, and 4 (1.6%) people declared other education status or provided no answer. Participants had, on average, 5.85 years of experience in volunteering (SD = 4.37) and 3.87 years of experience in the current volunteering organization (SD = 3.63). On average, participants collaborated with 3.92 organizations (SD = 4.51). In the six months before the pandemic (before March 2020), participants volunteered on average 20.52 h per month (SD = 52.42), and six months before filling out the survey (before January–February 2021), they volunteered on average 18.86 h per month (SD = 40.90). Sixty (24.5%) people declared that they volunteer in actions/seasonally, 84 (34.3%) in the long term, and 101 (41.2%) declared volunteering of both types.

Procedure

The study was questionnaire-based and performed online in January–February 2021. The research procedure and materials were approved before data collection by the Research Ethics Committee at The Maria Grzegorzewska University. The survey was anonymous. The announcement about the study was disseminated mainly through a mailing to all regional centers of volunteering, which were associated with the Polish Network of Volunteering Centres, as well as to nongovernmental organizations that offer volunteering opportunities. The study was described as A study of volunteers regarding personality, self-perception, and decision-making. All volunteers were to have been active in the year preceding the study and be between the age of 18 and 35. There was no remuneration for participating.

The first screen of the survey had a control question: "Which of these three words is not a name?" The aim was to exclude potential bots which could fill out the survey. After the introductory screen containing the study description, participants needed to confirm being a volunteer in the last year. Moreover, in random places between items of the standardized questionnaires, there were two attention control questions: This question checks your attention. Mark < an option > . People who answered incorrectly were removed from further analysis.

Measures

All measures are based on self-report. However, we employed measures using different response types to avoid the risks of common method bias (Kock et al., 2021). The details are provided below.

Social value orientation was assessed as a social value orientation angle obtained from the Social Value Orientation Slider Measure, A version (Murphy et al., 2014) with Polish instruction (Nowakowska, 2020b). The instrument is a game where the participants are asked to divide resources (points) between themselves and another (fictitious, imagined) game partner. The participants chose the most preferred resource allocation out of 9 options. The social value orientation angle takes values from -16.26 (utterly competitive) to 61.39 (utterly altruistic). The angle was computed using the algorithm by Baumgartner (n/d) shared on the website of Ryan O’Murphy, the author of the scale. Along with the social value orientation angle, the categorical description of the social value orientations displayed by participants is provided based on cutoff points.

Future time perspective was assessed using the Polish Short Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (Przepiorka et al., 2016; based on Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). The scale is a self-report and consists of 20 items forming four subscales: past negative, past positive, present hedonistic, and future. Participants marked their answers on a scale from 1 to 5. A sample item for future time perspective is: When I want to achieve something, I set goals and consider specific means for reaching those goals. Cronbach’s α for this subscale was 0.74.

Predicted probability of volunteering in three time horizons. The predicted probability of volunteering in one month, one year, and three years was assessed with three direct questions: Not taking into account the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, how probable it is for you (in percentage 0–100) to be a volunteer in (1) a month, (2) a year, (3) three years.

Analytic Strategy

First, from the initial sample of 282, 245 people were left out due to failure in attention checks and after an outlier analysis of the scores (people of z-scores in the subscales of independent variables ± 4 were removed from the database prior to analysis). Pearson’s r correlations were used to gain initial insights into the associations between the variables. The focal hypotheses were tested using multiple regression with interaction. Analyses were conducted in IBM SPSS 28.0.1.0 (IBM, 2021). Post hoc tests were done using the PROCESS 4.2 macro for SPSS by Andrew F. Hayes (Hayes, 2018). Bootstrapping for N = 5000 was employed for regression analysis and post hocs. All variables were standardized to z-scores before analysis.

Results

According to the classification of social value orientation types (Murphy et al., 2014), in the sample, none of the participants were competitive, 11 people (4.5%) were individualistic, 230 (93.9%) prosocial, and 4 (1.6%) altruistic. In Table 1, the correlations between variables are shown along with their means and standard deviations.

In the next step, regression with interaction analysis was performed to test the hypotheses. We construed three models, predicting three dependent variables: the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 month (Model 1), the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 year (Model 2), and the predicted probability of volunteering in 3 years (Model 3). We present the results of these analyses in Table 2.

Data from Table 2 show that in the case of the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 month, in the first step, the overall regression was statistically insignificant, F(3; 209) = 0.92; p > 0.05, and none of the predictors was statistically significant. In the second step, the overall regression was statistically significant, F(6; 206) = 6.11; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.126. The significant predictors were: social value orientation, B = 0.22; 95% CI [0.08; 0.36], p < 0.01; and the future time perspective and social value orientation interaction, B = .− 28; 95% CI [− 0.42; − 0.11], p < 0.01. Post hoc analysis indicated that future time perspective was related to the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 month only when social value orientation was low, B = 0.38; 95% CI [0.21; 0.55], and unrelated in the case of average (B = 0.12; 95% CI [− 0.01; 0.25]) or high (B = − 0.14; 95% CI [− 0.31; 0.04]) social value orientation. Figure 1 presents a visualization of this interaction effect.

In the case of the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 year, in the first step, the overall regression was statistically significant, F(3; 218) = 5.49; p < 0.01; adjusted R2 = 0.057, and the significant predictors were: younger age, B = − 0.16; 95% CI [− 0.30; − 0.02], p < 0.05; and length of experience as a volunteer, B = 0.26; 95% CI [0.11; 0.43]. In the second step, the overall regression was statistically significant, F(6; 215) = 9.09; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.180. The significant predictors were: younger age, B = − 0.17; 95% CI [− 0.32; − 0.04], p < 0.05; length of experience as a volunteer, B = 0.24; 95% CI [0.09; 0.40], p < 0.01; future time perspective, B = 0.13; 95% CI [0.02; 0.24], p < 0.05; social value orientation, B = 0.23; 95% CI [0.11; 0.33], p < 0.001; and the future time perspective and social value orientation interaction, B = − 0.23; 95% CI [− 0.35; − 0.13], p < 0.001. Post hoc analysis indicated that future time perspective was related to the predicted probability of volunteering in 1 year only when social value orientation was low, B = 0.35; 95% CI [0.19; 0.50], and average, B = 0.14; 95% CI [0.02; 0.26], and unrelated in the case of high social value orientation, B = − 0.07; 95% CI [− 0.24; 0.09]. Figure 2 presents a visualization of this interaction effect.

In the case of the predicted probability of volunteering in 3 years, in the first step, the overall regression was statistically significant, F(3; 218) = 7.46; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.081, and the significant predictor was the length of experience as a volunteer, B = 0.33; 95% CI [0.20; 0.48], p < 0.001. In the second step, the overall regression was statistically significant, F(6; 215) = 7.53; p < 0.001; adjusted R2 = 0.151. The significant predictors were: younger age, B = − 0.15; 95% CI [− 0.30; − 0.02], p < 0.05; length of experience as a volunteer, B = 0.32; 95% CI [0.18; 0.45], p < 0.001; social value orientation, B = 0.24; 95% CI [0.12; 0.37], p < 0.001; and the future time perspective and social value orientation interaction, B = − 0.14; 95% CI [− 0.30; − 0.01], p < 0.05. Post hoc analysis indicated that future time perspective was related to the predicted probability of volunteering in 3 years only when social value orientation was low, B = 0.21; 95% CI [0.05; 0.38], and unrelated in the case of average (B = 0.08; 95% CI [− 0.04; 0.21]) or high (B = − 0.04; 95% CI [− 0.21; 0.13] social value orientation. Figure 3 presents a visualization of this interaction effect.

Discussion

Based on the considerations of prosocial behaviors as being embedded in social and temporal fences (Joireman et al., 2001; Milfont & Gouveia, 2006), the aim of the study was to test whether volunteers of lower (more individualistic) versus higher (more altruistic) social value orientation differ in terms of how their future time perspective links to the intention to remain an active volunteer in three time horizons: a month, a year and three years. The results partially confirmed the hypotheses.

H1 was confirmed, as the social value orientation was indeed positively linked to volunteering intention in all three investigated time horizons. It is congruent with the view of volunteering as a collaborative, cooperative action involving other-orientation rather than selfishness (Gilbert et al., 2017). Moreover, it confirms the results obtained in previous studies on social value orientation's role in shaping voluntary prosocial behaviors, e.g., participation in research (McClintock and Allison, 1989) and other studies on volunteering specifically (Nowakowska, 2022). The result suggests that altruistically- or cooperatively oriented volunteers may be easier for organizations to retain than competitively oriented individuals, even for a long time. It is, however, worth noticing that in the sample, based on the cutoff points by the Social Value Orientation measure authors (Murphy & Ackermann, 2014), a vast majority of participants fell into the category of prosocial, and only a few into the categories of individualists or altruists. None of them were competitors. Therefore, the results, relying on a continuous metric, show the inclination toward individualism or altruism among prosocials rather than differentiate pure individualists and pure altruists. It should be considered when drawing further conclusions or new studies based on these results.

In the current study, it has also been found that future time perspective links to volunteering intentions for all investigated time horizons in the case of more individualistic volunteers, which partially confirms H2. There was no link between future time perspective and volunteering intentions for average or high social value orientation (thus, more altruistic than individualistic). Therefore, the results suggest that social value orientation is strong enough to display a willingness to engage in further volunteering, and future time perspective does not play a role then. It extends the results obtained by Maki and colleagues (2016), who suggested that, in general, the future time perspective relates to volunteers' beliefs and behaviors. Our study shows that it may be true for people who are less caring for others' outcomes. For altruistic volunteers, the cost–benefit calculation for short- and long-term benefits could be less crucial than for more individualistic ones. It may be due to the congruence between their altruistic values and their behavior. For them, prosocial behavior could be rewarding instantly (due to realizing their personal standard of helping others; see Kim et al., 2019) and in the long term (if they could see the positive results of their actions; Maki et al., 2016).

Only for people with low social value orientation (more individualistic), the higher the future time perspective, the higher the predicted probability of future volunteering engagement. It might be due to a utilitarian view of volunteer engagement in the case of individualistic people—they would engage as long as it serves their own needs (Lee & Brudney, 2009). As future time perspective is essential for planning and seeing future consequences (Mohammed & Marhefka, 2020), it could help competitors see the benefit for themselves in the long term. For example, it could facilitate thinking about volunteering as an element of reciprocal altruism—when a volunteer helps now, he or she could get help from others in the future (Chernyak-Hai & Halabi, 2018; Nowakowska, 2023). People low on future time perspective focus more on the short-term (Zimbardo & Boyd, 1999). If an individualistic person has such a feature, they have two obstacles to present willingness to continue volunteering. They are less motivated by the desire to achieve outcomes for the well-being of beneficiaries or the organization they work in than are more altruistic volunteers, as competitiveness promotes selfish orientation (Mudrack et al., 2012). At the same time, if they are also short-term oriented, they could have difficulty declaring themselves for long-term commitments that are not entirely congruent with their self-orientation.

For the control variables, we found that gender did not play a role in predicting future engagement in any time horizon of declaration. However, we must acknowledge that the sample was not balanced regarding gender distribution.

There was also an interesting pattern regarding age and length of volunteering experience. These variables did not play a role in the predicted probability of volunteering in one month. The reason behind this could be that the time horizon was so short that the volunteers of various ages and experiences did not predict any changes regarding that. For the predicted probability of volunteering in one year and three years, although age and length of volunteer experience were correlated, they were differently related to the dependent variables. The younger the volunteers, the more ready they were to declare that they would continue volunteering. However, the longer they were already volunteering, the more probable they found the continuation of their activity. The youngest persons were eighteen years old, typically a period of higher education in Poland. Such people could predict their engagement as more probable because they may have more time to volunteer than older young adults (as they typically do not have that many personal and professional commitments; Freeman, 1997). It is also possible that in younger volunteers, these declarations were more impulsive, whereas in older—more considerate, as impulsive decision-making is more characteristic of younger adults (Eppinger et al., 2012).

However, at the same time, as predicted, longer experience with volunteering was linked to a greater predicted probability of its continuation. It is probably a function of internalizing the role of a volunteer (Finkelstein & Penner, 2005). The longer one engages, the more difficult it is to give up due to habit, attachment to an organization and people with whom the activity is performed, and the benefits connected to volunteering. It is in line with research that suggests social connections may be more critical for a higher allocation of time for volunteering than self-actualization (Babula & Muschert, 2023).

We also need to acknowledge the data collection period—the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, uncertainty about the future was a general concern, accompanying people regardless of their sociodemographic characteristics (Koffman et al., 2020). As the predicted probability of further engagement in the current study was assessed in percentages, the more significant uncertainty about own plans could also translate into more cautious declarations.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

The current research advances the theoretical views on prosocial behaviors, taking into account social and temporal aspects of engagement in volunteering (Milfont & Gouveia, 2006). It shows that, indeed, congruent with our hypothesis, social value orientation is positively related to the intention to engage in further volunteering. It is a novel result as there is scarce data on the role of social value orientation in volunteering. Moreover, the study indicated that in people with low social value orientation (more competitive), future time perspective can serve as an individual difference related to this intention. Thus, if a person is not altruistic, the orientation on the future goals can help retain them as volunteers. It is a novel result that could be used in further studies to understand better how to encourage people not naturally inclined to care for others' welfare to engage in volunteering.

The study offers insights for organizations to plan development programs for volunteers. Organizations could use the results by developing volunteer cooperation skills to diminish individualistic inclinations. As our results suggest, enhancing a prosocial attitude toward others could further translate into a greater desire to continue volunteering engagement. For example, organizations could encourage volunteers to participate in team projects and activities that could integrate them as a group that operates collectively. Organizations should highlight future, long-term goals and potential achievements for less prosocial/more competitive volunteers. It could help them see personal benefits and become more keen to stay active. For example, during advertising volunteering, organizations could describe the potential positive consequences of engagement for the beneficiaries and volunteers. Volunteers could also be encouraged to keep track of their achievements at work and be rewarded with small remunerations. Organizations could also introduce motivation and award systems so that volunteers (especially those who are competitive) could have the opportunity to engage with a perspective of future achievement, which would be noticed and rewarded.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The current study is not free of limitations. First, it is based on cross-sectional data. There was a gender imbalance in the sample. Only one age group was investigated due to the research design, which makes the results non-applicable to other age groups of volunteers. The study was based on self-report questionnaires, limiting the measurement's objectivity. This method is also prone to the risk of social desirability bias in participants, and the results’ interpretations need to be considered. The study was also conducted in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic period, when volunteers engaged previously had their activity restricted, moved to an online mode, or changed in response to the current needs. Some volunteers could have been active only in the pandemic-related actions, given that prosocial activities were part of the social support landscape that emerged in response to lockdowns (Carlsen et al., 2021; Nowakowska, 2021). The social reality was also quite uncertain (regarding work circumstances, free time, and personal plans for the nearer and farther future, Koffman et al., 2020). Declaring intentions to engage in several time horizons could have been difficult for some participants. In the current study, volunteering was defined and researched as a general phenomenon, similar to a study by Maki and colleagues (2016). However, enlarging the sample and differentiating volunteers in terms of the types of activities they undertake (or targeting a specific group) could deepen the interpretation of the results.

Future studies could address these shortcomings. It is also worth it to design and evaluate programs for developing cooperative skills in volunteers and their future orientation to encourage them to remain active. Longitudinal, long-term studies would also help assess how cooperative versus altruistic volunteers tend to sustain their activity and what additional personal and contextual factors shape this decision.

Data Availability

The data can be accessed freely at Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/zn86x/

Code Availability

The code can be obtained on request when contacting the Corresponding author.

References

Arnocky, S., Milfont, T. L., & Nicol, J. R. (2014). Time perspective and sustainable behavior: Evidence for the distinction between consideration of immediate and future consequences. Environment and Behavior, 46(5), 556–582.

Babula, M., & Muschert, G. (2023). Does Maslow’s hierarchy of needs explain volunteer time allocations? An exploration of motivational time allowances using the American Time Use Survey. Journal of Public and Nonprofit Affairs. https://doi.org/10.20899/jpna.9.3.1-20

Baird, H. M., Webb, T. L., Sirois, F. M., & Gibson-Miller, J. (2021). Understanding the effects of time perspective: A meta-analysis testing a self-regulatory framework. Psychological Bulletin, 147(3), 233–267.

Bellido, H., Marcén, M., & Morales, M. (2021). The reverse gender gap in volunteer activities: Does culture matter? Sustainability, 13(12), 6957.

Carlsen, H. B., Toubøl, J., & Brincker, B. (2021). On solidarity and volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis in Denmark: The impact of social networks and social media groups on the distribution of support. European Societies, 23(S1), S122–S140.

Chernyak-Hai, L., & Halabi, S. (2018). Future time perspective and interpersonal empathy: Implications for preferring autonomy-versus dependency-oriented helping. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(4), 793–814.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530.

Côté, J. E. (2006). Emerging adulthood as an institutionalized moratorium: Risks and benefits to identity formation. In J. J. Arnett & J. L. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 85–116). American Psychological Association.

Crocetti, E., Moscatelli, S., Van der Graaff, J., Rubini, M., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2016). The interplay of self-certainty and prosocial development in the transition from late adolescence to emerging adulthood. European Journal of Personality, 30(6), 594–607.

Dwiggins-Beeler, R., Spitzberg, B., & Roesch, S. (2011). Vectors of volunteerism: Correlates of volunteer retention, recruitment, and job satisfaction. Journal of Psychological Issues in Organizational Culture, 2(3), 22–43.

Erikson, E. H., & Erikson, J. M. (1998). The life cycle completed (extended version). WW Norton & Company.

Finkelstein, M. A., Penner, L. A., & Brannick, M. T. (2005). Motive, role identity, and prosocial personality as predictors of volunteer activity. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 33(4), 403–418.

Flanagan, C., & Levine, P. (2010). Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children, 20(1), 159–179.

Freeman, R. B. (1997). Working for nothing: The supply of volunteer labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 15(1), S140–S166.

Gilbert, G., Holdsworth, S., & Kyle, L. (2017). A literature review and development of a theoretical model for understanding commitment experienced by volunteers over the life of a project. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 28(1), 1–25.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Hustinx, L. (2001). Individualisation and new styles of youth volunteering: An empirical exploration. Voluntary Action, 3(2), 57–76.

Jiranek, P., Kals, E., Humm, J. S., Strubel, I. T., & Wehner, T. (2013). Volunteering as a means to an equal end? The impact of a social justice function on intention to volunteer. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153(5), 520–541.

Joireman, J. (2005). Environmental problems as social dilemmas: The temporal dimension. In A. Strathman & J. A. Joireman (Eds.), Understanding behavior in the context of time: Theory, research, and application (pp. 289–304). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Joireman, J. A., Lasane, T. P., Bennett, J., Richards, D., & Solaimani, S. (2001). Integrating social value orientation and the consideration of future consequences within the extended norm activation model of proenvironmental behaviour. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(1), 133–155.

Kim, B. J., Kim, M. H., & Lee, J. (2019). Congruence matters: Volunteer motivation, value internalization, and retention. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 19(5), 56–70.

Koffman, J., Gross, J., Etkind, S. N., & Selman, L. (2020). Uncertainty and COVID-19: How are we to respond? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(6), 211–216.

Lee, Y. J., & Brudney, J. L. (2009). Rational volunteering: A benefit-cost approach. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 29(9/10), 512–530.

Maki, A., Dwyer, P. C., & Snyder, M. (2016). Time perspective and volunteerism: The importance of focusing on the future. The Journal of Social Psychology, 156(3), 334–349.

Marta, E., Guglielmetti, C., & Pozzi, M. (2006). Volunteerism during young adulthood: An Italian investigation into motivational patterns. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 17(3), 221–223.

McClintock, C. G. (1978). Social values: Their definition, measurement and development. Journal of Research & Development in Education, 12(1), 121–137.

McClintock, C. G., & Allison, S. T. (1989). Social value orientation and helping behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 19(4), 353–362.

Messick, D. M., & McClintock, C. G. (1968). Motivational bases of choice in experimental games. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 4(1), 1–25.

Metzger, A., Alvis, L. M., Oosterhoff, B., Babskie, E., Syvertsen, A., & Wray-Lake, L. (2018). The intersection of emotional and sociocognitive competencies with civic engagement in middle childhood and adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1663–1683.

Milfont, T. L., & Gouveia, V. V. (2006). Time perspective and values: An exploratory study of their relations to environmental attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 26(1), 72–82.

Mohammed, S., & Marhefka, J. T. (2020). How have we, do we, and will we measure time perspective? A review of methodological and measurement issues. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(3), 276–293.

Mudrack, P. E., Bloodgood, J. M., & Turnley, W. H. (2012). Some ethical implications of individual competitiveness. Journal of Business Ethics, 108, 347–359.

Murphy, R. O., & Ackermann, K. A. (2014). Social value orientation: Theoretical and measurement issues in the study of social preferences. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(1), 13–41.

Murphy, R. O., Ackermann, K. A., & Handgraaf, M. (2011). Measuring social value orientation. Judgment and Decision Making, 6(8), 771–781.

Nowakowska, I. (2020a). Prosociality in relation to developmental tasks of emerging adulthood. Psychologia Rozwojowa, 25(4), 15–25.

Nowakowska, I. (2021). Age, frequency of volunteering, and present-hedonistic time perspective predict donating items to people in need, but not money to combat COVID-19 during lock-down. Current Psychology, 42(20), 17329–17339.

Nowakowska, I. (2022). Volunteerism in the last year as a moderator between empathy and altruistic social value orientation: An exploratory study. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 10(1), 10–20.

Nowakowska, I. (2020b). Social Value Orientation Slider Measure by Murphy et al. (2011). Instruction in Polish. Open Science Framework.

Omoto, A. M., & Packard, C. D. (2016). The power of connections: Psychological sense of community as a predictor of volunteerism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 156(3), 272–290.

Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Van der Graaff, J. (2023). Prosocial behavior during adolescence and the transition to adulthood. In L. J. Crockett, G. Carlo, & J. E. Schulenberg (Eds.), APA handbook of adolescent and young adult development (pp. 559–572). American Psychological Association.

Przepiorka, A., Sobol-Kwapinska, M., & Jankowski, T. (2016). A Polish short version of the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 101, 78–89.

Rehberg, W. (2005). Altruistic individualists: Motivations for international volunteering among young adults in Switzerland. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 16(2), 109–122.

Schwartz, S. H. (1970). Moral decision making and behavior. In M. Macauley & L. Berkowitz (Eds.), Altruism and helping behavior (pp. 127–141). New York: Academic Press.

Shields, P. O. (2009). Young adult volunteers: Recruitment appeals and other marketing considerations. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 21(2), 139–159.

Simons, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Lacante, M. (2004). Placing motivation and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 16, 121–139.

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (2007). Social action. In A. W. Kruglanski & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: A handbook of basic principles (pp. 940–961). New York: Guilford Press.

Taniguchi, H. (2006). Men’s and women’s volunteering: Gender differences in the effects of employment and family characteristics. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(1), 83–101.

Van Lange, P. A., Bekkers, R., Schuyt, T. N., & Vugt, M. V. (2007). From games to giving: Social value orientation predicts donations to noble causes. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 29(4), 375–384.

Veludo-de-Oliveira, T. M., Pallister, J. G., & Foxall, G. R. (2015). Unselfish? Understanding the role of altruism, empathy, and beliefs in volunteering commitment. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 27(4), 373–396.

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (1999). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1271–1288.

Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2008). The time paradox. Free Press.

Funding

National Science Centre, Poland PRELUDIUM grant 2021/41/N/HS6/01312.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study materials and procedure were approved by Research Ethics Committee at The Maria Grzegorzewska University, approval number 3/2020. The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki (2001). All participants provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nowakowska, I. Altruists will be Altruists, but What About Individualists? The Role of Future Time Perspective and Social Value Orientation in Volunteers’ Declarations to Continue Engagement in Three Time Horizons. Voluntas (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00613-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00613-8