Abstract

Being a police officer is a very stressful job, characterized by occupational stressors that impact mental health and increasing work-family balance. Quantitative research is unable to clarify how police officers cope with the impact of work challenges on work-family balance. This study aims to understand how police officers narrate the impact of their work on their family experiences. Nineteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with Portuguese military police and civilian service forces working in the Northern region of Portugal. The interviews were transcribed and analyzed according to the principles of thematic analysis. The main themes indicate that participants are concerned about the work-family conflict. Both common and unique police officers’ perceptions of the impact of professional challenges on work-family balance emerged among both groups. Common work-family balance challenges for both civilian and military police officers included a negative impact on family dynamics and the sharing work experiences with family, but also recognized positive impacts of the profession on the family. For military police officers, making decisions regarding career advancement is a specific challenge. This study enables clinicians and other professional groups, such as commanders and politicians, to further develop a deeper understanding of these challenges and their different levels of impact. It also allows for the development of targeted strategies aligned with the unique needs of these professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Being a police officer is a highly stressful job, and recently, Tuttle and collaborators (2018) described four main stress sources: organizational, operational, external, and personal. Specifically organizational stress includes issues, such as the policing hierarchy, lack of support within the organization, shift work, lack of resources, restrictive policies, and judicial system inconsistencies (Fagan 2015; Violanti and Aron 1993). Operational stress pertains to exposure and response to critical incidents in an unusual and routinized way (Slate et al. 2007) and exposure to intense human suffering. Additionally, external factors include public scrutiny (Jones 2020), and, on a personal level, stress is related to the fact that they consider themselves on duty 24/7, to the absence at significant family events and also to work-family conflict (Fagan 2015). It should be noted that, in Portuguese institutions, a high number of police officers are initially placed in departments far from their area of residence, taking on average 15 years to get placed closer to their hometown (Cruz 2010).

Police culture promotes that police officers must be strong, minimize the impact, perform well, be emotionally regulated, and cognitively flexible. This culture also demands the omission of events or parts of events, either due to professional secrecy or by the need to convey an image of security and stability (Violanti 2003). The accumulation of these professional challenges, the potential risk to their lives, and organizational stress all impact on various levels, highlighting physical and psychological problems (Berg et al. 2003; Regehr et al. 2021; Rosa and Aranibar 2009), as well as work-family conflicts (Acquadro Maran et al. 2020). Researchers have shown that, although these professionals describe families as a resource that helps them cope with the different stressors and shields them against adverse effects (Jones 2020), work-related stress may also affect family members (Regehr and Bober 2005). This has consequences for family and marital relationships (Brodie and Eppler 2012; Roberts et al. 2013; Roberts and Levenson 2001; Spicer 2018), leading to deteriorating reactions that do not align with the emotional control expected in their profession (Violanti 2003).

Although an extensive body of research has been examining the negative consequences associated with the challenges inherent to police activity, including aggressive behaviors (Queirós et al. 2013), impact of numerous potentially traumatic exposures (Acquadro Maran et al. 2020; Beshears 2017; Geronazzo-Alman et al. 2017; Hammock et al. 2019; Maguen et al. 2009; Mona et al. 2019; Papazoglou 2013; Spicer 2018; Velazquez and Hernandez 2019), stress in routine work environment (Liberman et al. 2002; Maguen et al. 2009), work-family balance and its effects on families (Griffin and Sun 2018; Karaffa et al. 2015; Kaushal and Parmar 2018; Lambert et al. 2019), mental health barriers and stigma (Haugen et al. 2017), and psychological intervention strategies and programs (Au et al. 2019; Papazoglou 2017; Papazoglou and Tuttle 2018), little is known about how police officers narrate and cope with the impact of work challenges on work-family balance. In particular, there is limited understanding of how the demands and emotional repercussions of their work affect other areas of the officers’ lives.

Despite the increasing research on work-family balance in police officers (Frank et al. 2017; Griffin and Sun 2018; Lambert et al. 2019; Qureshi et al. 2019; Tuttle et al. 2018), there are still two main limitations to the studies on this topic. Firstly, there is a predominant reliance on quantitative studies, which are often considered to be reductive regarding the way these professionals perceive the impact of professional challenges in their lives. Secondly, there is a lack of studies with civil and military police, which would provide a better understanding of their realities. To the best of our knowledge there are no records of studies in this scope. Given the increasing impositions of a personal and professional daily life that is more and more demanding, it is essential to understand how police officers combine professional and personal challenges. In this regard, as qualitative data is often used to explore complex phenomena and gain an in-depth understanding of people’s experiences, perspectives, and behaviors (Braun and Clarke 2006), we believe that this is the method best suited to facilitate a more in-depth understanding of the realities experienced by these professionals, thereby giving them a voice.

This study aims to tackle the limitations identified in the literature, using semi-structured interviews, seeking to understand, in a systematic and in-depth way, police officers’ perceptions regarding impact of professional challenges on work-family balance, along with factors that may either mitigate or exacerbate this impact.

Method

Study Population and Design

Using semi-structured qualitative interviews about the impact of job demand on work-family balance, we explored the work environment and its characteristics in two groups of police forces (military and civil). We used an inductive thematic analysis that followed the guidelines developed by Braun and Clarke (2012). Thematic analysis is a qualitative method used to “identify, analyze and report patterns in the data” (Braun and Clarke 2006). According to the terminology of these authors, an essentialist paradigm was adopted as it was in the researcher’s interest to report experiences, meanings, and participants’ perceptions of reality along with some interpretation of the researcher (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Participant Recruitment and Data collection

Nineteen interviews were conducted with Portuguese police officers from two police forces. Given the need to make the sample as homogenous as possible, only males with minor children were selected, whether they were married, in a consensual union or divorced. Single men were not included in the sample. The participants were informed of the study by their superiors, and after this first contact, the snowball technique was used to access a larger number of officers. Interviews were analyzed as they were performed until data saturation was reached (i.e., no new themes emerged).

Prior to the semi-structured interviews, participants completed a brief questionnaire that included relevant variables such as rank patrol, duration of service, living situation, and work-home distance. If the participant presented clinically significant malaise, they were made aware of the need to see a mental health clinician but were not excluded from the study. The interviews, conducted by the first author with experience in psychological first aid and emotional stabilization, happened at the police station and lasted 21 to 120 min. Participants did not receive any monetary incentive for their participation.

Data collection procedures were approved by the institutional forces and the ethics committee of the university. Eligible participants provided written informed consent prior to entering the study. All data was anonymized to ensure the confidentiality and privacy of participants.

Qualitative Interview Protocol

The interview protocol was developed based on literature research, the study’s theoretical framework, our knowledge of police forces, and personal experiences as psychologists. One of the included questions was, for example, “How do you disconnect from work problems when you go home?.” Furthermore, although the interviews had a semi-structured script, the participants’ responses led to the inclusion of other questions that proved to be relevant. For instance, when participants introduced new concepts such as career progression or suicide, the interviewer induced further investigation by asking them to elaborate on their statements: “can you give me an example about...?”; “how did you feel when...?” (see Table 1).

Qualitative Analysis (Thematic Analysis)

To facilitate thematic analysis, all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim following Azevedo et al. (2017). Detailed notes were also recorded during the process, as well as possible analytical insights. The interviews were analyzed using NVivo12 software.

Following suggestions from Braun and Clarke (2006), the first author engaged in multiple in-depth readings of the data, before getting immersed in it. Second, the data was read again and coded to produce meaningful insights related to the raw data phenomena. Third, the coded data was collected and organized into higher-order themes. This process involved important judgment of the code similarities, code grouping, and creation of specific codes through inductive information. This dynamic process involved continuous revisions between codes, themes, and their relationships. At last, after deciding and doing some adjustments, the final themes were defined, named, and given a brief description to. It was when analyzing the interviews that we realized that the police groups were contrasting in some themes that emerged. Then, the groups were analyzed comparatively.

Qualitative Rigor and Trustworthiness

As a form of qualitative rigor and trustworthiness, we used several strategies. To improve credibility and to have greater internal consistency within each interview, the interview protocol was elaborated to include direct and indirect questions about the participant’s experiences as well as experiences of acquaintances (Krefting 1991). Regarding the transferability and because the generalization was important, we selected only participants whose experience represented this population (men, married, with minor children). To improve the dependability, we used a stepwise replication strategy in the coding process. Another co-author (GM) double-coded 40% of the interview transcription and coding. Likewise, the coded data included the context under which the discussion occurred, ensuring that the data collection process was related to the context. Additionally, peer examination was conducted. We solicited feedback on the data analysis at different stages throughout the study from team members and other researchers not directly involved in the process (Morse 2015). Co-authors assisted all the process through peer debriefing, where we dialogued about our interpretations. Finally, we discussed the process with a team of qualitative researchers, to increase confirmability.

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

The sample comprised 19 policemen, namely 11 military and eight civil policemen. The two groups of professionals had an average of 45.39 (SD = 4.83) years and 21.79 (SD = 4.61) years of professional experience. Fifteen participants (78.9%) were married or in a consensual union, and 4 (21.1%) were divorced. Each of them had at least one minor child. Most (N = 17) were low-rank patrol (89.47%), and only 7 (36.8%) considered themselves to be working away from their area of residence (Tables 2, 3 and 4).

Findings

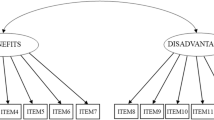

In this study, four main themes were found where civil and military police officers describe some unique and some common impacts of job demands on work-family balance (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). The impact of the profession on family dynamics stands out. The difficulties in planning routines, vacations, important family events and even the mental availability to be with relatives were narrated with anguish. There is also the struggle to decide whether to share professional experiences with the family, which is described as necessary, but ambivalent, becoming a barrier to communication and the well-being of the family and the couple. Despite all the challenges, both groups can identify positive aspects of their profession and view it with pride. Nevertheless, the dilemmas associated with (non-)career progression were specific sources of stress for military police officers. They proved to be the central theme for these professionals, in contrast to what is reported by civil police officers, where this theme did not emerge significantly.

Job Demand for Work-Family Balance Common in Both Groups

Negative Impact on Family Dynamics

All participants describe a high impact on family and family dynamics caused by professional characteristics (e.g., work on shifts, excessive workload, and adverse situations), organizing their narrative into two levels of impact: family and children and marital relationship.

Impact on the Relationship with Family and Children

This profession implies a huge rotation of shifts and even, sometimes, an excessive workload. Interviewees described how shift rotation and unpredictable schedules affected time with family and the impact of more stressful situations on quality time and physical and mental availability. All participants reported difficulties in managing family routines due to the shift’s rotation, as they could not manage work together with the routines of their children, having to take and pick them up from school, along with the incompatibility of schedules with their spouse that made it even harder to manage these routines. Likewise, the shifts and the absence at important family events (e.g., not being always able to be present at dinner, not being able to put the children to bed) and having difficulty spending family time regularly, due to the rotation of shifts, were described by the policemen with a lot of anguish, hurt, pain, and guilt.

When my son was born, I was away... out of the country. And my wife had to go through everything alone.... I saw my son the first time when he was a month old... and no one will ever take that away from me. I missed the birth of my son... my first son.

Besides these physical absences reported by the participants related to shift rotation and work demands, all interviewees reported that exposure to potentially traumatic events, namely crimes involving children, domestic violence scenarios, and unresolved issues at work made them unable to “switch off,” so they would go home thinking about work, which affected their mental availability for the family and impacted the quality of time spent with them. At the same time, the unpredictability of days off and working late made family planning difficult.

And then I’m not in the mental mood... not with the slightest bit of patience and at the smallest thing I yell at the girl

However, the existence of a support network is described by the participants as a way to minimize the impact of the difficulties in managing family routines, since it is described as facilitating the management of their children’s routines, as they helped them in their care, such as taking and picking them up from school, while they and their spouses are working and were not available to do so. In contrast, participants who reported not having a support network nearby left their children alone at home or many hours at kindergarten because they had no one to help them with these dynamics, describing feelings of anguish, guilt, and overload.

Impact on the Marital Relationship

Also, in this subtheme, police officers described similar experiences regarding how shift rotation, physical absences, and exposure to potentially traumatic events (PTE) impacted their marital relationship. Thus, interviewees stated that during absences, the spouses were the ones who took on family responsibilities, such as routines and childcare, and gave up their profession/career to be able to get a schedule compatible with the children’s needs due to their profession not being as flexible, which caused an overload on the spouse. It is also clear from the participants’ speech that the accumulation of several exposures to PTE made it difficult for them to maintain a good temper, projecting stress on the family, and altering their behavior, which caused conflicts between the couple, that reiterated over time, led to the relationship wearing out, impacting the marital relationship.

This profession has this particularity, and it’s normal that with all these things... you get home... it’s very hard for us to find someone who is in a good mood...

Sharing Experiences with the Family

In their professional performance, they are exposed to stressors that can come from either the field work (e.g., exposure to intense human suffering) or the work/institution environment (e.g., conflict between hierarchies and bureaucracies). Exposure to these stressors was described as triggering a need to vent about the experiences they have in their daily lives. However, although the officers acknowledged this need for sharing, it was often perceived as ambivalent. On the one hand, they are told that they should not and cannot share professional experiences outside the work environment due to professional confidentiality. On the other hand, they feel the need to talk to someone and vent the emotions associated with those experiences. Participants describe different positions in a continuum ranging from sharing everything, omitting some aspects, to a preference for managing problems by themselves. This position is defined as an intrinsic way for the professional to manage problems alone, as an attempt to protect the family from the situations to which they are exposed daily, as trying to avoid excessive concern from family members, or as a way to avoid adverse and activating memories for them. However, it is perceptible from the interviewees’ speech that when stressful work situations are too painful and affect them psychologically, they end up sharing these experiences, as well as discomfort and associated emotions, at home with their families, especially their spouses.

I happen to share... I do share... although... always with some reservations. I don't share everything. I don't share everything because I know how to defend myself and I know how to defend my own.

(Positive) Impact of the Profession on the Family

In contrast, “it’s not all bad,” and police officers also described the positive impact of the profession on the family, such as the family’s sense of pride, recognition, financial stability, and their personal development. The vast majority of respondents described that being a police officer provided the family with feelings of pride, with children having the ambition to follow their father’s profession. Likewise, the police profession is perceived by the family as selfless. The interviewees describe the profession’s recognition, importance, and value, being seen as heroes in its eyes. Additionally, the financial stability provided by the profession, which contributes to the support of the family, especially of the children, was narrated as one of the main motivations to continue in the profession. Besides this, the civil police officers can also identify an area not addressed by the military police officers, which is personal development. Thus, the civil police officers described how much their professional experience had contributed to their personal development and enrichment, either because of the people with whom they work daily or because of the countries, cities, and cultures they have had the opportunity to get to know in the work environment. Furthermore, the interviewees reported that the family functioned as a protective factor that helped them cope with the stressors from the work environment, being perceived as a refuge and an important source of support.

The kids at home sometimes...help...help... to forget all that.... Everyone comes into the house, currently helping to do the homework, but then they always want to play and it’s... “dad let’s do this, we have to do that... it’s easier... and that helps a lot. It ends up being a refuge

Therefore, the officers brought meaning to their profession, managing, despite all the challenges and difficulties they experience daily, to build a narrative with a feeling that not everything is bad, finding and valuing the positive aspects and trying, whenever possible, to maintain a balance between their individual and family needs.

I mean, it’s a profession... that... to me personally, but to many of my colleagues as well... gives a lot in return (...) That is, after all these years, the bills are well settled

Job Demands Specific to Military Police

Career Progression Decision-Making Process

When explaining how career advancement decision-making is weighed, participants describe that they ponder, along with their spouses, the (dis)advantages of advancement or non-advancement. The ambivalence of progression or non-progression varies and includes concerns about new roles at work associated with new responsibilities and new family routines, as well as the cost and benefits of these changes that would ultimately affect the entire household. Career progression is associated with positive consequences for most professions, with the benefits clearly outweighing the costs generated. Nevertheless, this is not always the reality in police forces. There were significant and important differences in how civil and military police officers report their experience of career progression or non-progression.

For the military policemen, ambivalence was related to career advancement which usually implies moving away from their families’ area of residence—for months or even years. Upon entering this institution, all military policemen reported expectations of career advancement. Three participants even decided to advance early in their career, for financial reasons or due to wanting to build a career in this profession. However, as the participants began to start a family, they reported the need for family stability, as moving away from home was perceived to have an impact on the family that was exacerbated by having children. At this point, they began to ponder, as a family, the decision of career advancement or non-advancement over prioritizing family. Thus, military policemen and their family evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of this decision on it and on a professional level. Military policemen who decide to advance in their careers are again forced to make other decisions—displacement of only themselves or removal of the whole family unit. In the participants’ discourse, the displacement of only the police officer led to the estrangement of the family, as well as to costs in the parental practice.

I didn’t see my son grow up.... I was from the 1st year he was born down there [in Lisbon], until he was 5...

On the other hand, the relocation of the household implies sacrifices from the spouse, as they might have to give up their profession to relocate and need to look for another job and would often be left without the family support network they had in their hometown, as well as sacrifices from their children who would have to constantly change schools and teachers and would not be able to have stable friendships. In contrast, from the participants’ perspective, the disadvantages of the decision not to progress in their careers or to interrupt them were the costs associated with career building and financial costs, essentially due to the salary gains that will not be achieved when there is no progression. In contrast, civil police officers describe their experience of career (non-)advancement differently. Regarding initial career progression, some participants say it took them a few years to get a position near their family’s area of residence “I spent 5 years in Lisbon, waiting for a vacancy here, in Porto.” The reality is that most of them find it easier to get placements near their area of residence. The civil policemen also explain that since it is a less hierarchical institution, with fewer effective personnel and a smaller organizational chart, when progressions occur, they are less frequent throughout the years of service (due to the smaller organizational chart) and that, therefore, they have not created as many dilemmas as with the military policemen, who have a more stratified and complex organizational chart.

I was 11 years as a (...) then I went to (...) to the course of (...) in more than 30 years, I was 1 year in formation (Lisbon)... and I always came back to Porto, I was always here, except for the time of the courses

For the military policemen, this theme was considered to cause a lot of stress, doubts, and insecurities. It was associated with dilemmas and losses, whatever the decision taken was. As opposed to the civil policemen that referred that the progression or non-progression in their careers was more related to their own will to invest in their professional careers, without this having a negative impact on the structure and dynamics of their families.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore and comprehend how military and civil police officers narrated their experiences and the impact of professional challenges on work-family balance. When analyzing the data, similarities and differences were found between the speeches of the two groups of participants. Shared and unique job demands on work-family balance emerged among military and civil police officers, reflecting different professional experiences and distinct levels of impact on work-family conciliation. Common work-family balance challenges for civilian and military police officers included negative impact on family dynamics and sharing work experiences with family. The specific challenge for military police officers included career advancement decision-making, both described as an unsolvable dilemma. However, despite all the challenges, both groups can identify positive gains from their profession, describing it with pride and a sense of belonging.

Our findings regarding challenges common to both groups are consistent with previous quantitative research (Dingman and Dingman 2020; Friese 2020; McCanlies et al. 2017; Regehr and Bober 2005; Tuttle et al. 2018). However, the results of this study deepen previous research by describing differences in the impact on work-family balance, specifically in terms of career progression for military versus civil police officers.

Although previous quantitative studies have described and emphasized the impact of occupational stressors reported by police officers (Hammer et al. 2005; Mona et al. 2019; Regehr et al. 2021), they have not been able to describe in depth the common and unique experiences of this impact. Qualitative work in this area and with this population is scarce. Yet, previous studies have focused on these professionals’ perceptions of their professional misconduct (Strote 2021) and on the impact of numerous potentially traumatic exposures (Hammock et al. 2019); however, they were unable to explore in depth the impact of occupational challenges on work-family balance.

In line with other studies (Magano et al. 2021; Queirós et al. 2020), Portuguese police officers consider their profession extremely stressful, exhausting, challenging, and very demanding in work-family balance. They also describe the impact on work-family reconciliation, emphasizing the difficulties in managing daily family routines with work demands, as well as the ambivalence between sharing or not sharing professional experiences and their impact. Even though a sense of stress and difficulty reconciling work and family was always present for both groups, civilian and military police officers described the impact of work analogously, except when the issue of career advancement was addressed. Challenges to career advancement were specific to military police officers, who described the decision-making process as ambivalent and an unsolvable dilemma, with high costs, whatever the decision was.

Despite recognizing the need to share feelings and emotions with their families, the police culture demands professional secrecy, as well as control and emotional immunity, promoting feelings of security and tranquility (Violanti 2003). Hence, sharing professional experiences with the family emerges as an ambivalent process. On the one hand, they prefer to solve their problems alone to avoid causing concern in their loved ones and disturbing memories themselves. On the other hand, when stressful situations are too painful, military and civilian police officers narrate the need to share, mainly the discomfort and associated emotions. Indeed, literature has shown that police officers tend to put their family in a “protective bubble” to shield them from the unpleasant and distressing aspects of work, making the family environment a separate refuge from the stresses and pressures of work (Miller 2005; Karaffa et al. 2015). According to the cognitive model of PTSD (Ehlers and Clark 2000), avoidance is a frequent response following exposure to potentially traumatic events that is widely used by police officers (Arble et al. 2018; Bishopp et al. 2018) and that, in the long term, can hinder the processing and integration of the traumatic experience into a narrative and preclude recovery (Foa and Kozak 1986). Individuals who do not express their emotions and experiences may involuntarily create a negative reinforcement and communication pattern in which emotions and experiences become increasingly feared (Arble and Arnetz 2017), thereby affecting their relationships, notably, the marital relationship (Karaffa et al. 2015; Papazoglou and Tuttle 2018), which are not compatible with such emotional control (Violanti 2003). Moreover, professionals seem to share more organizational problems, such as conflicts with superiors, with their spouses, than disruptive and adverse experiences. Therefore, the (non)sharing of experiences seems to depend more on the content and its impact rather than an intrinsic characteristic of the professional.

Additionally, the negative impact on family dynamics reported by police officers is related to the rotation of shifts and excessive workload, which negatively affects the management of family routines, family events and plans, and the time and quality spent with their families. Literature has described shift work as a significant predictor of family conflict (Burke and Mikkelsen 2007; Karaffa et al. 2015), and its constant changes disable police officers to manage childcare, since they are only home for a brief time, having to suddenly change plans, and missing momentous events (McCreary and Thompson 2006). Likewise, because of the high potentially traumatic exposure, the difficulty in disconnecting from work also affects the mental availability of the family (McCreary and Thompson 2006). While results show that the physical absences of police officers cause a burden on the spouse, the spouse may experience an emotional or psychological loss without experiencing a physical separation (Regehr and Bober 2005). Friese’s (2020) study of police officers’ wives indicated that the high workload of police officers causes the wives to have to adapt to traditional roles by changing their family schedule to take care of their home and feel like single mothers since they must deal with everything that encompasses the family alone and fully assume the care of their children. It is also known that repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of traumatic events (e.g., witnessing human suffering) can lead to a sense of being disconnected or of estrangement from others and a persistent negative emotional state, such as anger (American Psychiatric Association 2013), that sometimes, when accumulated, can culminate in conflict.

All this difficulty in managing routines and family dynamics seems to be minimized when children are older and, consequently, more autonomous (Karaffa et al. 2015). A close support network (nuclear and/or extended family) seems to facilitate the management of children’s routines when they are younger. This network appears to play a mitigating role, as it minimizes the impact of the difficulty of managing routines on the family. It aids in childcare while police officers and their spouses are working and are unavailable. Subjects who report not having a support network nearby describe an increased negative impact on the difficulty of managing routines in the family, as well as feelings of guilt and resentment. Studies conducted with police officers addressing the importance and role of social support emphasize its protective role in helping police officers cope with adversity and improve their mental health (Kshtriya et al. 2020).

Despite the negative impacts of the profession, the results emphasize its positive side. Being a police officer gives the family experiences of pride, recognition, and financial stability that motivate them to continue working in the profession. The feelings of recognition and pride experiences are corroborated by a study from Karaffa and co-authors (2015) conducted with police officers and their wives, which showed that about 87% of the wives reported being proud of their husband’s profession, and 72% agreed that their children were proud of their father’s career. Furthermore, the family works as a protective factor that helps them cope with work-related stressors, being perceived as a refuge and important support (Violanti 2003), protecting them from any negative impact (Castro-Chapman et al. 2018).

Although stress and some feeling of absence at crucial moments of family life were always present in the speeches of both groups, military policemen described career progression as an unsolvable dilemma in which the options (between prioritizing career or family) are felt as very limiting, and all of them carry within themselves the possibility of significant losses, which generates conflicting and competing expectations. Thus, military police officers describe an emotional overload regarding the need to make a career (non)advancement decision. Military policemen seem to adopt a narrative of resignation, in either option, marked by feelings of guilt and injustice towards the family, which may lead to the development of guilt in both the subject and his family. In contrast, those who choose to progress and move alone seem to feel guilty for leaving their family behind and being absent in their children’s lives to the detriment of professional achievement, describing a feeling of abandonment as well as spousal overload. If the household decides to move with the officer, the officer may feel responsible for the children’s constant school changes and consequent family instability, as well as the wife’s giving up her professional career for him to pursue his. This can be explained by the spillover model (Bakker and Demerouti 2013), which assumes that the individual’s experience in one of the psychosocial domains affects his experience in the other domain (work-family). However, civil police officers use a different narrative regarding career progression, and the feeling of an unsolvable dilemma is not perceptible. Career advancement is felt as an opportunity for the individual to grow and the whole family due to the gains it entails. The major justification for this difference seems to be related to movements and placements after promotion. While for civil police officers, career progression does not imply a physical separation from the family for an indefinite period of time, beyond the training time, which varies from a few months to a year; this is not the case for military police officers. This occurs because, usually, after the promotion course, civil elements often get placements in their area of residence and often even within their former department. This is associated with fewer changes in daily family and personal life.

To our knowledge, no previous study was found that addressed progression and its implications on police officers, but its inclusion in this study proved to be crucial, as it emerges in all interviews, of military police officers, with having an impact, which makes these results groundbreaking. Knowing that research results depend heavily on the methodology and theoretical lens used, these results illustrate the advantage of using a qualitative methodology to rigorously, systematically, and in detail gain an in-depth understanding of the perceptions and meanings attributed by police officers to the impact of professional challenges on work-family reconciliation, which would be difficult to achieve through other research methods (Taylor et al. 2015). Data obtained in this study represent experiences lived by these two groups of professionals, reflect the complexity of the impact of professional challenges on work-family reconciliation, add interpretive value to the analysis, and bring a new contribution to the international literature.

There are also limitations to this study, though. The fact that it is a qualitative study carried out in the North of the country may compromise the generalizability of the results. Nevertheless, the detail and depth described by the participants, as well as the rigor of the procedures used and the theoretical saturation achieved, allow us to overcome this limitation, which is not a qualitative studies’ objective. However, the impacts of the profession may be felt more in police officers residing in the North, since they are mostly deployed far from home. In contrast, those residing in Lisbon are usually deployed close to their residence, due to a larger number of vacancies available under the police organic law. Therefore, it would be interesting to conduct interviews with police officers from other parts of the country to see if the impact on the family remains. The fact that superiors mediated the interviews may have been another limitation, to the extent that participants may have felt coerced or morally obliged to participate in this study due to the importance given to respect for their superiors and hierarchy, which is very typical of this profession. Finally, while the sample size was large enough to divide participants into two groups that turned out to be contrasting in the progress of the data analysis, it was not large enough to compare across other potential subgroups (e.g., men vs. women; high vs. low patrol ranks; early career vs. late career, single vs. married men, with children vs. childless).

The in-depth results of this study allow us to improve our ability to understand the values and priorities of the participants and the factors causing family stress that may underlie work-family conflict, but also the psychological and emotional distress of these professionals, as well as professional performance. This study enables clinicians and other professional groups, such as commanders and politicians, to further develop a deeper understanding of these challenges and their different levels of impact and develop directly aligned and targeted strategies for these professionals, highlighting several levels of intervention. On a clinical level, due to exposure to potentially traumatic events on a recurrent basis, it would be crucial to provide periodic psychological screenings, post-critical event psychological support regularly (Gartlehner et al. 2013; Zohar et al. 2011), and easier access to psychological support when needed. Additionally, it would be important to provide strategies and skills, from initial training, to better manage and cope with the experiences and associated stress minimizing the impact on oneself and one’s family, as well as specialized continuing training (Newiss et al. 2022). Lastly, this study also emphasizes the need for policy guidelines, namely the spouse’s law and placements by NTUSP (nomenclature of territorial units for statistical purposes), thereby enabling career progression without too much impact on family dynamics and restructuring the organic law while maintaining organizational commitment by addressing hiring, progression, and retention issues (Fleming and Brown 2021; Newiss et al. 2022).

Data Availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, BS, upon reasonable request.

References

Acquadro Maran D, Zito M, Colombo L (2020) Secondary traumatic stress in Italian police officers: the role of job demands and job resources. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01435

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5)

Arble E, Arnetz BB (2017) A model of first-responder coping: an approach/avoidance bifurcation. Stress Health 33(3):223–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2692

Arble E, Daugherty AM, Arnetz BB (2018) Models of first responder coping: police officers as a unique population. Stress Health 34(5):612–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2821

Au WT, Wong YY, Leung KM, Chiu SM (2019) Effectiveness of emotional fitness training in police. J Police Crim Psychol 34(2):199–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-018-9252-6

Azevedo V, Carvalho M, Costa F, Mesquita S, Soares J, Teixeira F, Maia  (2017) Interview transcription: conceptual issues, practical guidelines, and challenges. Rev Enferm Ref IV Série(No 14):159–168. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV17018

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2013) The spillover-crossover model. New Frontiers in Work and Family Research 54–70

Berg AM, Hem E, Lau B, Loeb M, Ekeberg Ø (2003) Suicidal ideation and attempts in Norwegian police. Suicide Life-Threat Behav 33(3):302–312. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.3.302.23215

Beshears M (2017) Police officers face cumulative PTSD. police one.com

Bishopp SA, Leeper Piquero N, Worrall JL, Piquero AR (2018) Negative affective responses to stress among urban police officers: a general strain theory approach. Deviant Behav 40(6):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2018.1438069

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2(3):77–101

Braun V, Clarke V (2012) Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological 2:57–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Brodie PJ, Eppler C (2012) Exploration of perceived stressors, communication, and resilience in law-enforcement couples. J Fam Psychother 23(1):20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975353.2012.654082

Burke RJ, Mikkelsen A (2007) Suicidal ideation among police officers in Norway. Policing Int J Police Strategies Manag 30(2):228–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510710753234

Castro-Chapman PL, Orr SP, Berg J, Pineles SL, Yanson J, Salomon K (2018) Heart rate reactivity to trauma-related imagery as a measure of PTSD symptom severity: examining a new cohort of veterans. Psychiatry Res 574–580https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.024

Cruz S (2010) A relação trabalho-família em elementos policiais deslocados e não deslocados da área de residência. [The work-family relationship in police elements displaced and not displaced from the area of residence]. Instituto Superior De Ciências Policiais E Segurança Interna

Dingman RC, Dingman RC (2020) Rotating work schedules and work-life conflict for police (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University)

Ehlers A, Clark DM (2000) A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther 38(4):319–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

Fagan N (2015) Tactical police officers, romantic attachment and job-related stress: a mixed-methods study. ProQuest Dissertations Theses 2015:270

Fleming J, Brown J (2021) Policewomen’s experiences of working during lockdown: results of a survey with officers from England and Wales. Polic J Polic Pract 15(3):1977–1992. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paab027

Foa EB, Kozak MJ (1986) Emotional processing of fear. Exposure to corrective information. Psychol Bull 99 : 20-35 Emotional Processing of Fear : Exposure to Corrective Information. Psychol Bull 99(1):20–35

Frank J, Lambert EG, Qureshi H (2017) Examining police officer work stress using the job demands–resources model. J Contemp Crim Justice 33(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986217724248

Friese KM (2020) Cuffed together: a study on how law enforcement work impacts the officer’s spouse. Int J Police Sci Manag 22(4):407–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355720962527

Gartlehner G, Forneris CA, Brownley KA, Gaynes BN, Sonis J, Coker-Schwimmer E, Jonas DE, Greenblatt A, Wilkins TM, Woodell CL, Lohr KN (2013) Interventions for the prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults after exposure to psychological trauma. Comp Eff Rev 109

Geronazzo-Alman L, Eisenberg R, Shen S, Duarte CS, Musa GJ, Wicks J, Fan B, Doan T, Guffanti G, Bresnahan M, Hoven CW (2017) Cumulative exposure to work-related traumatic events and current post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City’s first responders. Compr Psychiatry 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.12.003

Griffin JD, Sun IY (2018) Do work-family conflict and resiliency mediate police stress and burnout: a study of state police officers. Am J Crim Justice 43(2):354–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-017-9401-y

Hammer LB, Cullen JC, Neal MB, Sinclair RR, Shafiro MV (2005) The longitudinal effects of work-family conflict and positive spillover on depressive symptoms among dual-earner couples. J Occup Health Psychol 10(2):138–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.10.2.138

Hammock AC, Dreyer RE, Riaz M, Clouston SAP, McGlone A, Luft B (2019) Trauma and relationship strain: oral histories with World Trade Center disaster responders. Qual Heal Res 29(12):1751–1765. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319837534

Haugen PT, McCrillis AM, Smid GE, Nijdam MJ (2017) Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 94:218–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001

Jones DJ (2020) The potential impacts of pandemic policing on police legitimacy: planning past the COVID-19 crisis. Polic J Policy Pract 14(3):579–586. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/paaa026

Karaffa K, Openshaw L, Koch J, Clark H, Harr C, Stewart C (2015) Perceived impact of police work on marital relationships. Fam J 23(2):120–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480714564381

Kaushal P, Parmar JS (2018) Work related variables and its relationship to work life balance-a study of police personnel of Himachal Pradesh. Productivity 59(2):138–147

Krefting L (1991) Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther 45(3):214–222. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.45.3.214

Kshtriya S, Kobezak HM, Popok P, Lawrence J, Lowe SR (2020) Social support as a mediator of occupational stressors and mental health outcomes in first responders. J Community Psychol 48(7):2252–2263. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22403

Lambert EG, Qureshi H, Keena LD, Frank J, Hogan NL (2019) Exploring the link between work-family conflict and job burnout among Indian police officers. Police J Theory Pract Principles 92(1):35–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258x18761285

Liberman AM, Best SR, Metzler TJ, Fagan JA, Weiss DS, Marmar CR (2002) Routine occupational stress and psychological distress in police. Policing 25(2):421–441. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510210429446

Maguen S, Metzler TJ, McCaslin SE, Inslicht SS, Henn-Haase C, Neylan TC, Marmar CR (2009) Routine work environment stress and PTSD symptoms in police officers. J Nerv Ment Dis 197(10):754–760. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181b975f8

Magano J, Vidal DG, Sousa HFPE, Dinis MAP, Leite A (2021) Validation and psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Coronavirus Anxiety Scale (CAS) and Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) and associations with travel, tourism and hospitality. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(2):427. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020427

McCanlies EC, Gu JK, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, Violanti JM (2017) Resilience mediates the relationship between social support and post-traumatic stress symptoms in police officers. J Emerg Manag 15(2). https://doi.org/10.5055/jem.2017.0319

McCreary DR, Thompson MM (2006) Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing: the operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. Int J Stress Manag 13(4):494–518. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.494

Miller L (2005) Police officer suicide: Causes, prevention, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health 7(2):101

Mona GG, Chimbari MJ, Hongoro C (2019) A systematic review on occupational hazards, injuries and diseases among police officers worldwide: policy implications for the South African Police Service. J Occup Med Toxicol 14(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-018-0221-x

Morse JM (2015) Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Heal Res 25(9):1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501

Newiss G, Charman S, Ilett C, Bennett S, Ghaemmaghami A, Smith P, Inkpen R (2022) Taking the strain? Police well-being in the COVID-19 era. Police J Theory Pract Principles 95(1):88–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X211044702

Papazoglou K (2013) Conceptualizing police complex spiral trauma and its applications in the police field. Traumatology 19(3):196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765612466151

Papazoglou K (2017) Examining the psychophysiological efficacy of CBT treatment for first responders diagnosed with PTSD: an understudied topic. SAGE Open 7(3):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017729407

Papazoglou K, Tuttle BM (2018) Fighting police trauma: practical approaches to addressing psychological needs of officers. SAGE Open 8(3):215824401879479. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018794794

Queirós C, Kaiseler M, Leitão da Silva A (2013) Burnout as predictor of aggressivity among police officers. Eur J Policing Studies 1(2):110–134

Queirós C, Passos F, Bártolo A, Faria S, Fonseca SM, Marques AJ, Silva CF, Pereira A (2020) Job stress, burnout and coping in police officers: relationships and psychometric properties of the organizational police stress questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(18):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186718

Qureshi H, Lambert EG, Frank J (2019) When domains spill over: the relationships of work–family conflict with Indian police affective and continuance commitment. Int J Offender Ther Comp Criminol 63(14):2501–2525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X19846347

Regehr C, Bober T (2005) In the line of fire: trauma in the emergency services

Regehr C, Carey MG, Wagner S, Alden LE, Buys N, Corneil W, Fyfe T, Matthews L, Randall C, White M, Fraess-Phillips A, Krutop E, White N, Fleischmann M (2021) A systematic review of mental health symptoms in police officers following extreme traumatic exposures. Police Pract Res 22(1):225–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1689129

Roberts NA, Leonard RC, Butler EA, Levenson RW, Kanter JW (2013) Job stress and dyadic synchrony in police marriages: a preliminary investigation. Fam Process 52(2):271–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01415.x

Roberts NA, Levenson RW (2001) The remains of the workday: impact of job stress and exhaustion on marital interaction in police couples. J Marriage Fam 63(4):1052–1067. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01052.x

Rosa B, Aranibar F (2009) Burnout syndrome in police officers and its relationship with physical and leisure activities. 1–17

Slate RN, Johnson WW, Colbert SS (2007) Police stress: a structural model. J Police Crim Psychol 22(2):102–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-007-9012-5

Spicer M (2018) Running head: The effects of police work on family life 1 The effects of police work on family life by Mercedes Spicer. 1–19

Strote J, Warner J, Scales, RM, Hickman, MJ (2021) Prevalence and correlates of spitting on police officers: new risks in the COVID era. Forensic Sci Int 322:110747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2021.110747

Taylor PJ, Snook B, Bennell C, Porter L (2015) Investigative psychology. (pp 165–186)

Tuttle BMQ, Giano Z, Merten MJ (2018) Stress spillover in policing and negative relationship functioning for law enforcement marriages. Fam J 26(2):246–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066480718775739

Velazquez E, Hernandez M (2019) Effects of police officer exposure to traumatic experiences and recognizing the stigma associated with police officer mental health: a state-of-the-art review. Policing 42(4):711–724. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2018-0147

Violanti JM (2003) Suicide and the police culture. In: Police suicide: tactics for prevention (pp 66–75). Charles C Thomas Publisher

Violanti JM, Aron F (1993) Sources of police stressors, job attitudes, and psychological distress. Psychol Rep 72(3):899–904. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.72.3.899

Zohar J, Juven-Wetzler A, Sonnino R, Cwikel-Hamzany S, Balaban E, Cohen H (2011) New insights into secondary prevention in post-traumatic stress disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 13(3):301–309. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2011.13.2/jzohar

Acknowledgements

The authors express appreciation to the police forces and the Institutions from the North of Portugal. Finally, the authors are grateful to the police officers who, generously and patiently, participated in this research.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). This study was conducted at the Psychology Research Centre (CIPsi/UM), School of Psychology, University of Minho, supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) through the Portuguese State Budget (UIDB/01662/2020), as well as through the funding of a research grant awarded to the first author; Foundation for Science and Technology (2021.05085.BD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (59th Amendment) and was approved by local ethics review boards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sousa, B., Mendes, G., Gonçalves, T. et al. Bringing a Uniform Home: a Qualitative Study on Police Officer’s Work-Family Balance Perspective!. J Police Crim Psych 38, 1025–1043 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-023-09619-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-023-09619-w