Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) form a heterogeneous, widespread group of disorders, generally characterized by progressive cognitive decline and neuropsychiatric disturbances. One of the abilities that seems particularly vulnerable to the impairments in neurodegenerative diseases is the capability to manage one’s personal finances. Indeed, people living with neurodegenerative diseases were shown to consistently present with more problems on performance-based financial tasks than healthy individuals. While objective, performance-based tasks provide insight into the financial competence of people living with neurodegenerative diseases in a controlled, standardized setting; relatively little can be said, based on these tasks, about their degree of success in dealing with the financial demands, issues, or questions of everyday life (i.e., financial performance). The aim of this systematic review is to provide an overview of the literature examining self and informant reports of financial performance in people living with neurodegenerative diseases. In total, 22 studies were included that compared the financial performance of people living with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease, or multiple sclerosis to a (cognitively) normal control group. Overall, the results indicate that people living with neurodegenerative diseases are more vulnerable to impairments in financial performance than cognitively normal individuals and that the degree of reported problems seems to be related to the severity of cognitive decline. As the majority of studies however focused on MCI or AD and made use of limited assessment methods, future research should aim to develop and adopt more comprehensive assessments to study strengths and weaknesses in financial performance of people living with different neurodegenerative diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (MS), form a heterogeneous, widespread group of disorders that can generally be characterized by a progressive decline of cognition and neuropsychiatric disturbances (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hardiman & Doherty, 2016; Simon, 2017). These disease characteristics can lead to functional impairments in complex, higher-order as well as more basic activities of daily life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). One of the abilities that seems to be particularly vulnerable to the impairments in neurodegenerative diseases is the capability to manage one’s personal finances (Griffith et al., 2003; Marson et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2013; Sudo & Laks, 2017).

Being able to adequately handle financial tasks, such as paying bills, budgeting, or taking out insurance, is crucial for successful independent living. Difficulties in handling finances can have adverse personal and legal consequences (Engel et al., 2016; Triebel et al., 2018) and may lead to financial insecurity, debts, poverty, or even financial abuse (Dong et al., 2011; Engel et al., 2016; Manthorpe et al., 2012; Marson et al., 2000; Okonkwo et al., 2008). Despite this demonstrable importance in everyday life, financial capability has received relatively limited scientific attention in the context of neurodegenerative diseases. Specifically, clinically oriented research into financial capability is lacking, and most existing studies focus on dementia or AD rather than on other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Marson et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2013). Early recognition and evaluation of difficulties in financial capability is especially significant in people living with neurodegenerative disease, however, as it may enable researchers and clinicians to identify and timely offer the required type and level of support. Moreover, recent studies suggest that problems with certain aspects of financial capability, including financial decision-making and susceptibility to financial scams and exploitation, may reflect the accumulation of neurodegenerative pathology in the earliest stages of the disease process (i.e., prior to the onset of noticeable cognitive impairments) and could signal subsequent cognitive decline (Fenton et al., 2022; Kapasi et al., 2021). In line with this, it has been suggested that for some neurodegenerative diseases, a decline in financial capability could mark the progression from the mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage to the dementia stage (Gerstenecker et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2008, 2013).

When exploring the literature on financial capability and neurodegenerative diseases, it becomes clear that the terms financial ability, competency, capacity, and capability have been used almost interchangeably with slight differences in meaning across disciplines (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Within the context of the present study, terminology will be used as introduced by Appelbaum et al. (2016), in order to ensure clarity and consistency throughout the text. Appelbaum et al. (2016) defined financial capability as the management of one’s finances in a way that serves one’s personal needs and goals. In the evaluation of financial capability, a distinction can be made between financial competence and financial performance. According to the definition of Appelbaum et al. (2016), financial competence is generally assessed in a controlled setting and refers to an individual’s financial skills as reflected by their financial knowledge (e.g., their knowledge about the concept of money or online banking procedures) and their financial judgment. Financial performance, on the other hand, reflects real-world functioning and refers to an individual’s degree of success in dealing with financial demands, issues, or questions in the context of all stressors and resources in their personal environment. Successful financial performance thus requires both sufficient financial competence, as well as the presence of the abilities to implement financial decisions, and the possibility to use these abilities in everyday life (Appelbaum et al., 2016).

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis by Bangma et al. (2021) showed that people living with neurodegenerative diseases consistently present with more problems on performance-based financial tasks than healthy individuals, and that the degree of these problems seems to be related to the severity of cognitive decline. Indeed, minor cognitive difficulties that accompany normal aging might already have a negative influence on financial task performance and financial literacy (Bangma et al., 2017; Finke et al., 2017), although normal aging could also positively influence performance on financial tasks due to increased financial knowledge and experience, and the more stable affective processing that is associated with advancing age (Bangma et al., 2017). However, while such performance-based financial tasks may form an adequate measure of financial competence, relatively little can be said still, based on these studies, regarding the everyday financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative diseases. As the contextual factors in an individual’s environment can have a positive as well as a negative influence on their financial performance, a discrepancy may exist between an individual’s performance on structured financial tasks as applied in a controlled setting and their financial performance in daily life (Appelbaum et al., 2016). For example, if an individual with limited financial competence is supported by others in dealing with their financial matters (e.g., a caregiver sets up automatic bill-paying for rent and other necessities), they may show deficiencies on financial competence tasks, but still be successful in their everyday financial performance. If, on the other hand, an individual for example suffers from depression, this does not necessarily affect their financial competence either, but the depressive symptoms could negatively impact their ability to meet the financial demands of daily life (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Because of this potential discrepancy between task and daily-life performance, self and informant reports of an individual’s degree of success in dealing with their everyday financial demands, issues, or questions form an important, complementary source of information to performance-based financial competence tasks in determining financial capability. Moreover, self and informant reports can be used to assess financial capability at a different level than performance-based financial tasks. While performance-based tasks usually take place in a highly controlled setting, where individuals are asked to maximize their performance, self and informant report measures often require the individual to rate their daily-life performance over, for example, the past month (Fuermaier et al., 2015). Thus, whereas performance-based measures reflect an individual’s optimal performance at the moment of assessment, self and informant report measures provide information about an individual’s typical performance, averaged over longer periods of time (Fuermaier et al., 2015; Toplak et al., 2013). Indeed, previous research shows that subjective (self or informant report) and objective (performance-based) measures do not necessarily assess the same constructs (Fuermaier et al., 2015; Koerts et al., 2012; Toplak et al., 2013), suggesting that the use of self and informant report measures can offer distinct and valuable information about the financial capability of people living with neurodegenerative disease.

In this context, it is important to mention, however, that as compared to performance-based tasks, self and informant report measures rely more strongly on adequate insight into the daily-life functioning of an individual (Wadley et al., 2003). In people living with neurodegenerative disease, cognitive decline can cause reduced insight into one’s financial abilities (Gerstenecker et al., 2019), which may consequently lead to over or underestimations of their own financial performance. In a like manner, informant reported measures are susceptible to inaccuracy as informants may not always have the opportunity or time to make reliable observations of an individual’s current financial performance (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Given their susceptibility to bias, it should thus be emphasized that self or informant reports must be used to complement rather than substitute performance-based financial tasks. As shown in Table 1, measures of financial competence and financial performance have different strengths and limitations, and information on both types of measures is needed to gain insight into the financial capability of people living with neurodegenerative disease.

As the aforementioned study by Bangma et al. (2021) has reviewed studies that evaluated the performance on financial competence tasks of people living with neurodegenerative diseases, the aim of this study thus is to complement their findings by providing an overview of the literature examining self and informant report assessments of financial performance in these patient groups. By addressing assessments of financial performance, this study can provide valuable insight into the everyday financial functioning of people living with neurodegenerative disease in the context of their personal environment (see Table 1). In combination with the knowledge we have about financial competence assessments (Bangma et al., 2021), this will add to our understanding of the potential strengths and weaknesses in financial capability of people living with neurodegenerative disease, which is needed to develop and offer tailored support. The specific aim of this study thence was to determine the type and extent of subjectively reported problems in financial performance of people living with different neurodegenerative diseases as compared to the reports of a (cognitively) normal control group or as compared to an earlier point in time. If possible, the self and informant reports of financial performance were also compared between people living with different neurodegenerative diseases. A further aim was to explore what measures or variables are associated with the financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative disease. To this end, the existing literature on neurodegenerative diseases and self or informant reported financial performance has been systematically searched and analyzed.

Method

Study Selection Procedure

A systematic search of the available literature addressing financial capability (including financial performance) and neurodegenerative diseases was carried out according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009). Journal articles were searched through the databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science. Primary keywords for the literature search were related to neurodegenerative diseases, and included, for example, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, OR dementia. Secondary keywords were related to financial capability, and included terms such as financial performance, finances, OR money management (for a complete list of primary and secondary keywords and further clarification of the chosen keywords; see Appendix 1). A combination of primary and secondary keywords (e.g., dementia [AND] financial performance) had to appear in either the title or abstract of the articles. Only peer-reviewed articles that were written in English were included in the review.

The selection criteria for this systematic review were as follows: studies were included when they (a) included at least one relevant patient group that was diagnosed according to published criteria (e.g., according to DSM-5 or ICD-10 criteria), (b) included a group comparison between the relevant patient group(s) and a (cognitively) normal control group ((C)NC group) or adopted a longitudinal design, and (c) reported the outcomes of a structured self or informant report assessment of financial performance (e.g., a questionnaire or interview) or of a structured self or informant report measure that includes a subscale of at least one item on financial performance. Studies were excluded when they (a) only included a mixed patient group (e.g., a “dementia” group), (b) primarily focused on financial risk taking (e.g., impulsive buying), (c) primarily focused on (pharmacological) intervention effects, or (d) primarily focused on self or disease-awareness of the patient group(s) (i.e., reported solely on the relation or discrepancy between objective and subjective measures or between self-reported and informant reported measurements). Self or informant reported assessments were considered measures of financial performance only if they directly addressed an individual’s degree of success in dealing with their everyday financial demands, issues, or questions (after Appelbaum et al., 2016). Measures that were indirectly related to financial performance, such as questions on financial status or whether an individual has a representative payee, were not considered in this review. Additionally, items on (independence in) shopping were also not included as the abilities required to shop independently certainly include, but are not limited to, financial skills only. For example, in the more detailed Instrumental Activities of Daily Living – Compensation scale (IADL-C) (Schmitter-Edgecombe et al., 2014), one of the items that refers to shopping skills includes whether the individual is able to efficiently plan the sequence of stops on a shopping trip.

The literature search for the systematic review was finalized on the 12th of February 2021, resulting in a literature list of 7031 articles, from which duplicates were removed (see Fig. 1). The retrieved literature was supplemented with relevant literature cited in the articles found (manual search; Fig. 1). Titles and abstracts of a remaining 2914 studies were screened to see whether these studies addressed the topic at hand. After this screening, 395 studies remained, which were read in full in order to identify those articles that did not fulfill the selection criteria listed above. These articles were subsequently excluded (see Fig. 1). In total, 22 studies were included in the review.

Flow diagram of the systematic search and review process according to the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Moher et al., 2009)

Content Analysis

After the study selection procedure was completed (see Fig. 1), a content analysis was conducted for the included studies. The results were extracted and organized in table format according to diagnosis of the relevant patient group(s), including the following aspects; first author, country and year of publication, study design, sample characteristics (i.e., demographic and disease characteristics), adopted financial performance assessment, measure or item, source (i.e., self or informant report), and the main study outcomes considered relevant for the research question at hand. Relevant study outcomes included outcomes of comparisons between neurodegenerative disease group and a (C)NC group or comparisons between different neurodegenerative disease groups and longitudinal analyses regarding the financial performance assessments, as well as reported associations of other measures/variables with the financial performance assessments used. If a study included more than one participant group, only those groups for which outcomes on the financial performance assessment were reported and were described in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. In line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, (comparisons with) mixed patient groups (e.g., a dementia group) were not listed in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, as it is not possible to draw clear conclusions about individuals with a specific neurodegenerative disease based on this information. Study outcomes were all reported in close accordance with the results reported in the original studies, and, if reported on, group differences were considered significant at the alpha levels used in the original studies. If possible, effect sizes were calculated for the relevant group comparisons based on reported statistics or group means, making use of www.psychometrica.de (Lenhard & Lenhard, 2016). Via this website, all effect sizes were converted to Cohen’s d. Effect sizes in the order of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 can be interpreted as small, medium, and large, respectively (Cohen, 1969).

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

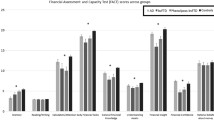

A modified version of the QUADAS-2 tool (Whiting et al., 2011) was used to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of each of the included studies. The QUADAS-2 tool can be used to assess risk of bias in four key domains: (1) patient/participant selection, i.e., the selection of the neurodegenerative disease and (C)NC groups; (2) index test, i.e., the financial performance assessment; (3) reference standard, i.e., the use of normative data or pre-defined cut-offs for the level of financial performance; and (4) flow and timing, i.e., the flow of the participants through the study, assessments, and analyses. The QUADAS-2 was originally designed to assess the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies (Whiting et al., 2011), but, as recommended by the authors, the signaling questions used to help reach judgment on the risk of bias were tailored to better fit with the type of studies included in the present review. The signaling questions used to assess the risk of bias for each of the QUADAS-2 domains are provided in Appendix 3 (Table 11). Based on the answers to these signaling questions and narrative descriptions of the results, the risk of bias within the included studies was judged as being high, low, or unclear for each of the four domains. The first three QUADAS-2 domains (i.e., patient selection, index test, and reference standard) were furthermore considered in terms of the level of concern regarding applicability to the review question. The level of concern regarding applicability was also rated as high, low, or unclear. We did not aim to exclude studies based on the risk of bias or applicability judgments. Further, as recommended by the authors, the QUADAS-2 tool was not used to generate a numerical quality score (Whiting et al., 2011). Instead, the results of the QUADAS-2 assessments were summarized in table format for each of the individual studies (see Table 8), and overall results were displayed graphically in Fig. 2.

Results

In total, 22 studies were included in this review (see Fig. 1; Appendix 2 (Table 10)). All studies made use of a self or informant reported assessment, measure, or subscale of at least one item to study financial performance in people living with MCI (k = 18), AD (k = 8), PD (k = 1), or MS (k = 2). Regarding the use of questionnaires or subscales on financial performance, 14 studies (i.e., 64%) made use of a subscale that included 1 to 3 items on financial performance, one study (i.e., 5%) made use of a subscale of more than three financial performance items, and four studies (i.e., 18%) used a full questionnaire, addressing various aspects of financial performance. Three studies (i.e., 14%) used a different form of assessment for financial performance, i.e., clinician ratings of the “level of financial independence” (Kenney et al., 2019) and the “mental competence to make financial decisions” (Lui et al., 2013), and family reports of the occurrence of specific problems with financial management (Terada et al., 2019). Seven of the included studies (i.e., 32%) only described the outcomes of a self-report assessment, 13 studies (i.e., 59%) only described the outcomes of informant reported assessments for the patient group(s), and one study (i.e., 5%) described both self and informant reported outcomes on the financial performance assessment. For one study (i.e., 5%), it was unclear, based on the information provided, whether the financial performance assessment was self or informant reported.

A detailed description of all instruments, subscales, or items on financial performance used in the included studies is provided in Table 2. An overview the study characteristics and relevant study outcomes is given in Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. The overall interpretation of the most important study outcomes for each of the individual studies is summarized in the Conclusion column of Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, and a synthesis of the outcomes in the context of the present review is laid out in-text. Finally, the results of the QUADAS-2 quality assessment and risk of bias evaluation are described in-text, summarized in Table 8, and displayed graphically in Fig. 2.

Financial Performance in People Living with MCI

Characteristics of Included MCI Groups

Eighteen studies investigated self or informant reported financial performance of people living with MCI (see Tables 3 and 5), evaluating a total of 2382 MCI participants. The mean age of the participants ranged from 67.1 to 82.9 years (weighted average = 70.7 years). Since Kenney et al. (2019) only reported on the descriptive characteristics of their total sample, it must be noted that the mean age of the MCI group in their study could not be included in the calculation of the weighted average.

For all 18 studies, the presumed MCI etiologies of the participant groups were either unknown or not reported. The diagnostic criteria for MCI that were applied in the different studies generally distinguished between two major clinical subtypes of MCI: amnestic MCI (aMCI) and non-amnestic MCI (naMCI). Depending on the number of cognitive domains that are impaired, these clinical subtypes can be further divided into single-domain aMCI or naMCI, or multiple-domain aMCI or naMCI (Petersen, 2004; Winblad et al., 2004). Eight studies (i.e., 44%) included people living with single or multiple-domain aMCI, and one study (i.e., 6%) included both an aMCI and an naMCI group. In four studies (i.e., 22%), the MCI group was mixed (including aMCI and naMCI participants), and five studies (i.e., 28%) did not report on the clinical subtypes of MCI included in the MCI group(s).

MCI Compared to Cognitively Normal Controls

Comparing self or informant reported financial performance of people living with MCI and cognitively normal controls participants (CNCs), the results of 15 of the 18 studies (i.e., 83%) indicated that more problems in financial performance were reported for/by people living with MCI than for/by cognitively normal controls. Thirteen studies found significant differences between the reported financial performance for the MCI and cognitively normal control groups, and two studies did not report on significance levels between the cognitively normal control and MCI groups, but results were in line with the MCI group having more problems in financial performance than the cognitively normal controls (Brown et al., 2011; Kenney et al., 2019). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the comparisons between the MCI and cognitively normal control groups could be derived for eight of these 15 studies and ranged from small to large, with the majority being considered as medium effects (see Tables 3 and 5). The type of problems in financial performance reported for/by people living with MCI were diverse and included problems with paying bills and handling money (e.g., calculating change), the organization of financial or tax records, finance and correspondence, and financial management (e.g., writing checks, balancing a check book, managing a budget or business affairs). In line with this, problems were reported for people living with MCI in “global financial capacity” and on several domains of the current financial capacity form (CFCF) (Gerstenecker et al., 2019; Griffith et al., 2003). Several studies furthermore reported people living with MCI to need (more) assistance in or to be (more) dependent on others in their financial management (see Tables 3 and 5). Finally, in three of the 18 studies (i.e., 17%) comparing the reported financial performance of MCI participants and cognitively normal controls, no (significant) between-group differences were found. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) in these studies (k = 3) could be interpreted as negligible or small (Ahn et al., 2009; Lui et al., 2013; Ogama et al., 2017).

Looking at the self and informant reported assessments separately, all six studies (i.e., 100%) that described the outcomes of a self-report assessment found that significantly more problems in financial performance were reported by people living with MCI than by cognitively normal controls. Of the 12 studies that described the outcomes of informant reported assessments for the MCI groups, eight studies (i.e., 67%) found significant differences between the MCI and cognitively normal control groups, while two more studies (i.e., 17%) did not report on significance levels between the MCI and cognitively normal control groups, but the results were in line with the MCI group having more problems in financial performance than the cognitively normal controls (Brown et al., 2011; Kenney et al., 2019). Finally, two studies (i.e., 17%) did not find significant between-group differences in the informant reports. For the study by Ogama et al. (2017), it was unclear, based on the information provided, whether the financial performance assessment was self or informant reported, but this study yielded no significant differences between the MCI and cognitively normal control groups.

Longitudinal Findings

Apart from a cross-sectional comparison between the MCI and cognitively normal control groups at baseline, Tuokko et al. (2005) also applied a longitudinal design, by comparing the MCI group to a cognitively normal control group at two points in time, with a five-year interval. Although sample sizes were very small for the longitudinal analysis, and results should be viewed with caution, they concluded that, among the people not reporting impairments in their money management at baseline, a significantly larger percentage of people living with MCI than cognitively normal controls reported impairments in this area after five years (see Table 3).

Financial Performance in People Living with AD

Characteristics of Included AD Groups

Eight studies investigated self or informant reported financial performance of people living with AD (Tables 4, 5 and 6), evaluating 824 AD participants in total, with a mean age range of 71.0 to 82.2 (weighted average = 77.4 years). Six of these studies (i.e., 75%) only included people living with (very) mild AD. In one study (i.e., 13%), participants in various stages of AD were included and subclassified for later analyses according to total MMSE scores (MMSE range: 15–30), while in another study (i.e., 13%), the disease stage of the AD group was not specified.

AD Compared to Cognitively Normal Controls

All eight studies (i.e., 100%) found the reported financial performance to be worse for people living with AD than for cognitively normal controls. The effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the comparisons between the AD and cognitively normal control groups could be derived for six of the eight studies and ranged from small to large, with the majority of studies finding large effects (see Tables 4, 5 and 6). Of the six studies (i.e., 75%) that only included people living with (very) mild AD, five studies found significant group differences, and one study did not report on significance levels between the AD and cognitively normal control groups, but results were still in line with the mild AD group having more problems in financial performance than the cognitively normal controls (Brown et al., 2011). Reported problems in financial performance for the (very) mild AD groups included problems in handling finances, the organization of financial records, financial management (e.g., writing checks, paying bills, managing check book), tax management, and all domains of the CFCF (see Table 5). As compared to cognitively normal controls, more individuals living with mild AD were furthermore found to need assistance in or to be incapable of financial management (Griffith et al., 2003) or rated by clinicians to be mentally incompetent to make daily financial decisions (Lui et al., 2013). Including a group of people living with AD for whom the disease stage was not specified, Cheon et al. (2015) found that the scores on the managing finances item were significantly higher (indicating poorer functioning) for the AD group than for the NC group. Lastly, Ogama et al. (2017) included people in various disease stages of AD and also concluded that significantly more problems in financial performance were reported for people living with AD as compared to cognitively normal controls. Subclassifying their sample into three groups according to total MMSE score furthermore led the authors to conclude that the ability to handle finances decreases significantly with increasing cognitive impairment (see Table 5). Looking at the source types that were used, seven of the eight studies that investigated the financial performance of people living with AD described the outcomes of an informant reported assessment for financial performance (Tables 4, 5, 6 and 7), one study additionally described the outcomes of a self-report assessment (Gerstenecker et al., 2019), and for one study it was unclear, based on the information provided, whether the assessment was self or informant reported (Ogama et al., 2017). Irrespective of the source type used, all eight studies (i.e., 100%) found the reported financial performance to be worse for people living with AD than for cognitively normal controls.

(Mild) AD Compared to MCI

Six studies investigated differences in financial performance between individuals diagnosed with aMCI and people living with AD (see Table 5). The results of all six studies (i.e., 100%) indicated that more problems in financial performance were reported for/by the (mild) AD groups than for/by the aMCI groups.

Financial Performance in People Living with PD

The study by Cheon et al. (2015) investigated informant reported financial performance in 72 people living with PD, including a group of cognitively normal participants living with PD and a participant group living with PDD (see Table 6). The results showed that the reported financial management abilities did not differ significantly between the cognitively normal PD group and an NC group (negligible to small effects). However, the reported difficulty was found to be significantly higher in the PDD group than in the PD and NC groups (medium to large effects). Furthermore, whereas the reported financial performance of the PDD group did not differ significantly from an AD group regarding the actual scores (small effect), the cognitive scores (i.e., scores corrected for having a motor disability) of the PDD group were significantly lower (indicating better functioning) than those of the AD group (large effect).

Financial Performance in People Living with MS

Two studies were included that looked at the difference in self-reported difficulties in financial performance between people living with MS and NC participants (NCs) (see Table 7). In total, 102 people living with MS participated in these studies, and the mean age of the participants ranged from 47.9 to 51.6 (weighed average = 50.0 years). Goverover et al. (2016) concluded that people living with MS reported significantly more problems in money management than NCs, as reflected by the total scores on the Money Management Survey (MMS) (medium effect). On item level, the MS group showed a significantly greater likelihood than the NCs to have increased problems with regard to operating an ATM, owning debt for bills they have not paid, and needing to borrow money. Goverover et al. (2019) split their sample of MS participants into two groups, including an inefficient and an efficient money management MS group. As the cut-off for group assignment was partly based on the scores on the MMS itself, it was not surprising that the percentage of participants reporting problems on the MMS was higher in the MS inefficient money management group as compared to the MS efficient money management group and the NCs on all but one item (i.e., “don’t often check change”). In contrast, the percentages of participants in the MS efficient money management group reporting problems on the MMS items were low, and highly similar to the percentages found in the NC group. According to the authors, these results suggest that not all individuals living with MS have problems with money management, and that the money management abilities of some people living with MS may be comparable to those of individuals without MS.

Associations of Financial Performance with Demographics, Disease Characteristics, Neuropsychological Measures, and Other Variables

Associations with Financial Performance in People Living with MCI or AD

Gender

Two studies found that in the MCI group, (possibly) combined with the cognitively normal control group, women reported significantly more problems in financial performance than men (Kim et al., 2009; Tuokko et al., 2005; see Table 3). Contrastingly, Lui et al. (2013) found that, when combining the cognitively normal control, aMCI, and mild AD groups from their study, no significant difference in gender ratio was observed between individuals who were found to be mentally competent to make daily financial management decisions, and those who were found to be mentally incompetent.

Age

Tabira et al. (2020) found that for both cognitively normal elderly and people living with very mild AD, the independence in the ability to handle finances decreased with advancing age. Importantly, this decrease in independence was found to start in a younger age group in people living with AD than in cognitively normal controls, and the decreasing slope with age was steeper in the very mild AD group than in the cognitively normal control group. In contrast, two other studies performed regression analyses (see Tables 3 and 5 for an overview of included variables) in a combined sample of MCI participants and cognitively normal controls (Tuokko et al., 2005), or a combined sample of aMCI and AD participants (Ogama et al., 2017), but did not identify age as a significant independent risk factor/predictor for reported problems on the financial performance item.

Cognitive Functioning

Charernboon and Lerthattasilp (2016) examined the relationship between MMSE scores and financial performance in participants without cognitive impairments, with MCI, and with mild, moderate, or severe dementia (diagnoses not specified). When looking for the optimum cut-off score, the authors found that a score of 24 or lower on the MMSE had the best sensitivity (0.84) and specificity (0.97) for differentiating individuals who were able versus unable to independently organize their finances. The organization of finances was therewith shown to be the first activity of daily living to be impaired along the stages of cognitive decline. Combining the aMCI and AD groups, Ogama et al. (2017) performed a multiple logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors for impairments in the ability to handle finances. In their first model, they found white matter hyperintensity in the frontal lobe to the only significant predictor (see Table 5 for an overview of included variables). In their second model, several variables were added as potential risk factors, rendering white matter hyperintensity in the frontal lobe as an insignificant predictor, but MMSE scores as a significant predictor of financial performance. This significant association between MMSE scores and the financial performance item seems to be in line with the finding that more problems were reported in financial performance for AD participants with moderate and lower MMSE scores (20–23 and 15–19) than for AD participants with relatively high MMSE scores (24–30), people living with aMCI and cognitively normal controls (Ogama et al., 2017). Contrastingly, two other studies did not find a significant association between MMSE scores and financial performance in the aMCI, mild AD (Gerstenecker et al., 2019), or cognitively normal control groups (Gerstenecker et al., 2019; Mariani et al., 2008).

Finally, the separate analyses performed by Mariani et al. (2008) in the aMCI and cognitively normal control groups revealed no significant associations between financial performance and comorbid illnesses, or performance on neuropsychological tests for episodic memory, language, attention/executive functioning and praxis. In contrast, Tuokko et al. (2005) found that, in a combined group of cognitively normal control and MCI participants, seven neuropsychological tests in four cognitive domains (i.e., memory, verbal abilities, visuo-constructional ability, and attention and processing speed) taken together in one model could significantly predict present financial performance. Performance on these same seven tests at T1 furthermore contributed significantly to the prediction of future difficulty in handling finances at T2 (i.e., five years later), and specifically, individuals with poorer memory at T1 were shown to be more likely to have difficulty in financial performance at T2.

Associations with Financial Performance in People Living with MS

Goverover et al. (2016) found that in the MS group (possibly combined with the NC group), more problems in financial performance were significantly associated with a higher reported dysfunction on an instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scale, and on a questionnaire for everyday life task performance, social interactions, and problem-solving. Self-reported financial performance scores were not significantly associated, however, with affect symptomatology, or with performance-based test scores in the domains of learning and memory, executive functions, and processing speed and working memory.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The methodological quality and risk of bias of all 22 included studies was assessed using a modified version of the QUADAS-2 tool (Whiting et al., 2011; see Appendix 3 (Table 11)). The results of the QUADAS-2 assessments for each of the individual studies are summarized in Table 8. Regarding the patient/participant selection, twelve studies (i.e., 55%) were judged as having a high risk of bias, eight studies (i.e., 36%) as having a low risk of bias, and for two studies (i.e., 9%) the risk of bias was unclear. The mixed results in this domain were mostly due to differences in the recruitment method for the neurodegenerative disease group(s). Most of the studies with a high risk of bias did not use a random or consecutive sampling method for the participant groups, while most studies with a low risk of bias did include a consecutive patient sample. Using a consecutive sampling method can reduce the risk of bias in a study as all eligible participants at the same hospital or clinic, for example, will have an equal chance of being included in the study, regardless of their performance on the index test. Contrastingly, the studies with a high risk of bias regarding the patient/participant selection mostly made use of purposive or convenience sampling. While widely adopted in patient studies, convenience sampling methods are prone to various forms of research bias and provide with a less reliable representation of the population than random or consecutive samples. For example, eligible patients who present with more cognitive impairments, or potentially more problems on the index test, might be less eager to volunteer for participation and could therefore be less likely to be represented in the recruited sample.

With regard to the index test (i.e., the financial performance assessment), the risk of bias was judged as being high for eighteen studies (i.e., 82%) and as low for four studies (i.e., 18%). For the majority of included studies, the risk of bias was high because the index test was considered inappropriate (i.e., too limited) to assess the multidimensional construct of financial performance. Furthermore, none of the included studies clearly described the use of a reference standard, such as normative data or a pre-defined cut-off for the level of difficulty in financial performance of the participant groups. The risk of bias with regard to the reference standard was therefore judged as being high for all included studies (i.e., 100%). In terms of flow and timing, nineteen studies (i.e., 86%) were judged as having a low risk of bias, as (almost) all participants in these studies both received the index test (i.e., the financial performance assessment) and were included in the analyses for the index test. For three of the included studies (i.e., 14%), the flow of the participants through the study, including the assessments and analyses, leads to a high risk of bias. Regarding the judgments of applicability, there was a low level of concern for all included studies (i.e., 100%) that the included patients did not match the review question. This was due to the fact that the selection criteria of the present review stated that only patient groups diagnosed according to published criteria were included, and that mixed patient groups (e.g., dementia groups) were excluded. Contrastingly, there was a high level of concern for the majority of included studies (i.e., 68%) that the index test differed from the review question at hand. While this review aims to address the construct of financial performance, the majority of index tests used were judged as being too limited to assess this broad construct in full. Finally, as no clear reference standard was defined or described in any of the included studies, the applicability to the review question of the reference standard was considered to be unclear for all 22 studies (i.e., 100%). The overall results of the risk of bias evaluation, including the judgments of applicability, are displayed graphically in Fig. 2.

Discussion

In the evaluation of financial capability, a distinction can be made between financial competence and financial performance. While financial competence is usually assessed in a controlled setting by means of performance-based financial tasks, financial performance reflects real-world functioning, and refers to an individual’s degree of success in dealing with the financial demands, issues, or questions of everyday life (Appelbaum et al., 2016) (see also Table 1). As a previous study by Bangma et al. (2021) reviewed studies evaluating the performance on objective financial competence tasks of people living with neurodegenerative diseases, the aim of the present review was to complement their findings by providing a systematic overview of the literature examining self and informant reported financial performance in these patient groups. In total, 22 studies were included that all compared the reported financial performance of people living with an neurodegenerative disease to a (C)NC group. The vast majority of the studies included people living with MCI of unknown etiologies or people living with AD (k = 19), one study focused on PD(D), and two studies addressed financial performance in people living with MS. Apart from between-group comparisons, associations between the assessments of financial performance and demographic and disease characteristics as well as neuropsychological measures and other variables were explored. Further points for discussion include a critical evaluation of the subjective assessment methods for financial performance used in the included studies, outcomes of the quality assessment and risk of bias evaluation, the limitations of the present review, and, finally, recommendations for future directions of research.

Financial Performance in People Living with Neurodegenerative Diseases

The majority of included studies suggest that subjectively reported financial performance is poorer for people living with neurodegenerative diseases than for cognitively normal individuals. In line with the findings on objective financial competence tasks as reviewed by Bangma et al. (2021), the studies on MCI or AD furthermore indicate that the degree of self or informant reported problems in financial performance seems to be related to the severity of cognitive decline.

Representing a (transitional) state of cognitive functioning between the changes associated with normal aging and dementia, MCI is often considered a prodromal stage of AD related dementia or other types of dementia. For all included studies, the presumed MCI etiologies were either unknown or not reported. MCI is characterized by concern about a change in cognitive function, and an objective decline of cognition in one or more cognitive domain, while independence in functional activities is preserved (Albert et al., 2011; Grundman et al., 2004; Petersen, 2004; Petersen et al., 1999, 2001). Regarding this latter diagnostic criterion of MCI in particular, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for mental disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5) states that “the cognitive deficits do not interfere with capacity for independence in everyday activities” and that “complex instrumental activities such as paying bills or managing medications are preserved” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder, para. 1). The finding of the present review, namely, that the majority of studies including people living with MCI (i.e., 83%) found the reported difficulty in financial performance to be (significantly) higher in the MCI than in the cognitively normal control groups, which was substantiated by mostly medium effect sizes, appears to be in stark contrast to this diagnostic criterion. In this context, it should also be noted, however, that the DSM-5 additionally states that for complex instrumental activities “greater effort, compensatory strategies or accommodation may be required” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Mild Neurocognitive Disorder, para. 1) for cognitive impairments to be considered mild, which could still be in line with the findings of this review. Indeed, the reporting of increased problems in financial performance compared to a normal control group does not necessarily correspond to a loss of independence but could also amount to the MCI groups having greater difficulty in performing daily financial tasks such as paying bills, yet still managing to do so on their own. However, several of the included studies specifically reported people living with MCI to be (more) dependent on others in their financial performance as compared to cognitively normal controls (see Tables 3 and 5) which is, in turn, clearly not in keeping with a preservation of independence in IADL as stated in the DSM-5. Constituting one of the complex IADL, financial performance therefore seems vulnerable to relatively mild impairments in cognition. Importantly, the studies using a questionnaire addressing several domains of financial performance showed that while some aspects of financial performance may indeed already be impaired in the milder stages of cognitive decline, other aspects, such as basic money skills and the comprehension of financial concepts, were generally reported to remain intact in people living with (a)MCI (Gerstenecker et al., 2019; Griffith et al., 2003). These domains thus appear to be less sensitive to mild impairments in cognition. Consistent with previous findings on objective financial competence tasks (see Bangma et al., 2021), the reported problems in financial performance for people living with MCI therefore appear to be less severe compared to the later stages of cognitive decline.

Representing the more severe stages of cognitive decline, all studies including people living with (mild) AD showed the informant reported financial performance of the AD groups to be worse than for cognitively normal controls, which was confirmed by mainly large effect sizes. As supported by the studies including a cognitively normal control, MCI, and AD group (Table 5), the findings of the present systematic review suggest a decreasing slope that may be observed in subjectively reported financial performance from normal cognition, to MCI, to (mild) AD. Specifically differentiating between MCI and severity stages of AD related dementia, the study by Ogama et al. (2017) for example showed financial performance to significantly decrease with increasing cognitive impairment as expressed by total MMSE scores. Addressing several domains of financial performance, the studies by Griffith et al. (2003) and Gerstenecker et al. (2019) further indicated all domains of the CFCF (i.e., basic monetary skills, financial conceptual knowledge, cash transactions, checkbook management, bank statement management, financial judgment, bill payment, knowledge of assets/estate, and investment decisions; see Table 2) to be affected in people living with mild AD as compared to cognitively normal controls, including the domains that were found to still be relatively intact in the (a)MCI groups. It is, however, important to note that this conclusion is based on cross-sectional studies. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm whether such a decreasing slope regarding financial performance indeed exists when considering the transition from normal cognition, to MCI, to (mild) AD.

The findings of the three studies addressing financial performance in PD(D) and MS seem to substantiate the notion that subjectively reported financial performance is related to cognition. While, as compared to cognitively normal controls, similar levels of financial performance were, for example, reported for people living with PD who were considered cognitively normal, people living with PDD were reported to have significantly more difficulty in financial performance than the cognitively normal controls. The financial performance of people living with PDD was shown to be largely comparable to the financial performance of people living with AD (Cheon et al., 2015). In a like manner, more problems in financial performance were reported for people living with MS than for NCs (Goverover et al., 2016, 2019). Yet, Goverover et al. (2019) concluded that this finding does not apply to all people living with MS. The financial performance of some people living with MS may be comparable to the financial performance of people without MS, which could possibly be explained by differences in cognition between people living with MS.

Associations of Financial Performance with Demographics, Disease Characteristics, Neuropsychological Measures, and Other Variables

Apart from looking at financial performance across diagnostic groups, several studies evaluated the potential relations between subjective reports of financial performance, demographic and disease characteristics, and various other subjective and objective neuropsychological measures within groups. Taking the large differences between these studies into account with regard to which relations were studied, which participant groups were included in the analyses, and the type of relational analyses conducted (e.g., correlational or regression analyses), no definite conclusions can be drawn based on the present review regarding these relations. Importantly, several of the included studies do however provide some indication that demographic characteristics (i.e., Kim et al., 2009; Tabira et al., 2020; Tuokko et al., 2005), global cognition (i.e., Charernboon & Lerthattasilp, 2016; Ogama et al., 2017), and specific cognitive functions (i.e., Tuokko et al., 2005) may be associated with subjective reports of financial performance in people living with different neurodegenerative diseases as well as in cognitively normal individuals. The potential influence of such variables on subjective reports of financial performance in both the present review and future studies can therefore not be ruled out. In the present review, not all included studies that observed significant between-group differences in age or gender ratio, for example, controlled for these differences in their analyses. In these studies, between-group differences in demographic characteristics may consequentially have affected relevant study outcomes, which adds to the risk of bias in terms of participant selection within these studies (see Table 8). Future research should thus aim to evaluate the characteristics, measures, and variables associated with financial performance measures in a more systematic manner in order to more firmly establish which factors may have an effect on self or informant reports of financial performance in people living with neurodegenerative disease. In this regard, future studies should also aim to address factors other than cognition or basic demographics (i.e., age or gender) that may hold relevant relations with financial performance. Factors such as prior levels of financial experience (e.g., Marson et al., 2000), financial literacy, socioeconomic status (see Appelbaum et al., 2016), and income level (Bangma et al., 2017), for example, have been associated with aspects of financial capability, yet, based on the included studies, their influence on the financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative diseases still remains to be explored.

Evaluation of Subjective Assessments for Financial Performance

Financial performance constitutes a broad and multidimensional construct that may include numerous financial tasks such as paying bills, budgeting, or taking out insurances, thus requiring various conceptual, procedural, and judgmental financial skills as well as more general affective and cognitive abilities (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Referring specifically to an individual’s real-world performance (Appelbaum et al., 2016), it becomes clear, based on the definition alone, that the concept of financial performance cannot be fully captured in one single questionnaire item or subscale. However, of the studies included in the present review, the majority made use of 1 to 3 self or informant report items that addressed financial performance in people living with neurodegenerative diseases, specifically inquiring about specific aspects of financial performance only (e.g., difficulty/independence in paying bills; see Table 2). Consequently, these studies all pose a high risk of bias in terms of the assessment used (i.e., the index test) as the adopted methods are considered inappropriate to address the broad construct of financial performance (see Table 8; Fig. 2). This limited manner of assessing subjectively reported financial performance is particularly problematic as the outcomes of the present review indicate that people living with different neurodegenerative diseases report to/are reported to experience more difficulty in this area than cognitively normal individuals. Clearly, the current assessment methods used cannot comprise such problems in full.

Indeed, only four of the included studies made use of an entire questionnaire solely focused on financial performance, providing a more comprehensive picture of the difficulties in financial performance reported for/by people living with neurodegenerative disease (Gerstenecker et al., 2019; Goverover et al., 2016, 2019; Griffith et al., 2003). First, the MMS (Hoskin et al., 2005; see Table 2), used in the studies by Goverover et al., (20162019), consists of 11 factual questions about difficulties in daily money management activities, making the questionnaire relevant for the identification of concrete problems in financial performance. At the same time, the MMS appears less fitting for the evaluation of the relative strengths in financial performance an individual may have, as the items are all phrased in a rather negative manner (e.g., “do you pay the bills late?”). The questionnaire furthermore includes a few items that specifically inquire about financial situations that could be considered less common or more extreme. The item on whether someone has lost their accommodation for not paying rent in particular seems to have led to a floor effect in the study groups included by Goverover et al., (2016, 2019). A final disadvantage of the MMS as a measure for financial performance is that the questionnaire was developed using a sample of people living with acquired brain injury (Hoskin et al., ). Since this comprises a broad and heterogeneous group, the questionnaire may not necessarily be suitable for all participant groups, including people living with a specific neurodegenerative disease.

In the studies by Griffith et al. (2003) and Gerstenecker et al. (2019), the CFCF (Wadley et al., 2003) was used as a measure of financial performance. This questionnaire addresses various financial domains (i.e., basic monetary skills, financial conceptual knowledge, cash transactions, checkbook management, bank statement management, financial judgment, bill payment, and knowledge of assets/estate) on the basis of which an overall financial performance score labeled “global financial capacity” can be calculated (see Table 2). Since the CFCF includes items on complex as well as more basic financial abilities, the questionnaire seems to provide a comprehensive picture of the financial performance of an individual or a group. It should be noted, however, that some aspects of financial performance still remain unaddressed in the CFCF. Important aspects that are not considered, for example, include knowledge of personal income, regular financial liabilities, insurances, loans, or debts, the ability to set personal financial goals and plan ahead financially (e.g., planning for retirement), budgeting skills, and the ability to save money. Nevertheless, out of the assessment methods used in the studies included in the present review, the CFCF appears to be the most comprehensive instrument for financial performance that has been adopted to date. Currently, we would therefore recommend to use this instrument in research and clinical practice to assess the financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative disease. Particularly in combination with the corresponding performance-based Financial Capacity Inventory (Griffith et al., 2003; Marson et al., 2000), which addresses the same financial domains as the CFCF, both the self and informant report versions of the CFCF can provide useful insight into the strengths and weaknesses in financial capability of an individual or group. For one of the two included studies that used the CFCF (i.e., Gerstenecker et al., 2019), the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for the comparisons between the three study groups could be calculated based on the information provided in the study. For the comparisons between the informant reports for the cognitively normal control, aMCI, and mild AD groups, the effect sizes for all nine financial domains and the overall financial performance score were large (see Table 5). For the comparisons between the self-reports of the cognitively normal control, aMCI and mild AD groups, the effect sizes ranged from small to large, with most effect sizes being interpreted as medium (see Table 5). Within this context, it is important to mention that the large effect sizes were predominantly determined by the comparison between the cognitively normal control and mild AD groups.

Finally, instead of using a questionnaire, item, or subscale, Kenney et al. (2019) and Lui et al. (2013) included a clinician rating. Whereas these ratings seem to have been based on comprehensive information (i.e., patient interviews or informant interviews, questionnaires and medical records), the outcome measures used to address financial performance were still limited, as they were either dichotomous (i.e., mentally competent/incompetent to make financial decisions) or trichotomous (i.e., fully dependent/needs assistance/independent in financial management). Therefore, these kinds of clinician ratings do not seem useful to fully capture the level of financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative disease.

Apart from more thoroughly addressing difficulties in financial performance, comprehensive questionnaires or interviews can also be used to shed light on the domains of financial performance that are still relatively intact in people living with neurodegenerative diseases. Such evaluations of both the relative strengths and weaknesses in financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative diseases are of the utmost importance to identify the required type and level of support, while at the same time determine domains of financial performance in which autonomy can be preserved. Whereas the present review does indicate people living with neurodegenerative diseases to be more vulnerable to impairments in financial performance than cognitively normal individuals, it should thus be emphasized that this does not necessarily apply to all domains of financial performance (e.g., Gerstenecker et al., 2019; Griffith et al., 2003), or to all (people living with) neurodegenerative diseases. In their study, Lui et al. (2013), for example, stress that despite the significance of their between-group findings, more than half of the participants living with mild AD were still found mentally competent to make day-to-day financial decisions based on the clinician ratings (see Table 5). These kinds of findings are particularly relevant in the evaluation of financial performance, as they show that having neurodegenerative disease does not mean that a person lacks the capacity to manage all aspects of their finances per se. In this context, it should also be noted that the quality assessment and risk of bias evaluation (Table 8 and Fig. 2) indicated that in addition to the use of a control group, none of the included studies clearly described the use of a reference standard, such as normative data, or pre-defined cut-offs to determine the participants’ level of financial performance. While most studies found that the neurodegenerative disease participants scored significantly worse on the financial performance assessment than the cognitively normal controls, these between-group differences do not necessarily indicate people living with neurodegenerative disease cannot perform a certain financial task, but solely that they perform worse than cognitively normal individuals. Reference standards such as normative data or cut-off scores are needed to interpret the assessment scores in the context of a condition or to determine whether scores on the financial performance assessment deviate from the financial performance of a normative sample, large enough to represent the general population. To gain further insight into the financial capability of people living with different neurodegenerative diseases, it is thence highly recommended that future studies aim to develop, adopt, and adequately report on more comprehensive assessments for financial performance and compare outcomes of these assessments to both cognitively normal controls and to normative samples that represent people living with neurodegenerative disease or the general population. Rather than using a small number of self and informant report items that inquire about specific aspects of financial performance only, comprehensive assessments could for example include questionnaires (e.g., the CFCF) or interviews that address financial performance across several domains.

Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

For all included studies, the methodological quality and risk of bias was assessed by making use of a modified version of the QUADAS-2 tool (Appendix 3 (Table 11)). As this tool was originally designed to assess the quality of diagnostic accuracy studies (Whiting et al., 2011), not all domains were found optimally fitting for the type of cross-sectional studies included in the present review. The domain addressing the reference standard in particular turned out not to be applicable to the included studies. As explained above, none of the included studies clearly described the use of a reference standard, which we defined as either normative data or a pre-defined cut-off for the level of financial performance. However, by tailoring the signaling questions to this review (Appendix 3 (Table 11)), the QUADAS-2 quality assessment that was carried out still provides a good indication of what aspects of the included studies pose the greatest risk of bias. Overall, the risk of bias in terms of participant selection was mixed due to the heterogeneity in recruitment methods for the neurodegenerative disease groups in particular, and the risk of bias regarding flow and timing could generally be considered low (Fig. 2). In accordance with our evaluation of the assessment methods used, as discussed above, the largest risk of bias within the included studies therefore concerned the conduct and interpretation of the index test (i.e., the financial performance assessment). For the vast majority of studies, the assessment method used was considered inappropriate (i.e., too limited) to fully address the multidimensional construct of financial performance (Fig. 2). When interpreting the results of this review, this high risk of bias in terms of the index test, as well as the absence of reference standards for the interpretation of the participants’ level of financial performance, should be taken into account.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research

The results of the present review have to be interpreted with care as several limitations need to be acknowledged. A first limitation that manifests itself on review level is that only a limited number of studies could be included (k = 22) in the present review, and that the vast majority of included studies focused on people living with AD or people living with MCI. Consequently, no conclusions can be drawn, based on the present review, about the financial performance of individuals with other common neurodegenerative diseases, such as frontotemporal dementia or Huntington’s disease. This systematic review has, therefore, identified a gap in the current evidence base. More research is needed concerning subjectively reported financial performance in people living with neurodegenerative diseases in general, and neurodegenerative diseases other than AD or MCI specifically. Further, all of the included studies have adopted a cross-sectional design, while only one study additionally included a longitudinal analysis (Tuokko et al., 2005). The longitudinal analysis performed in this study can moreover be considered as suboptimal, since the sample sizes were very small, and financial performance was only studied over time in people living with MCI and cognitively normal controls who did not report impairment on the financial item at baseline (see Table 3). As the present review indicates that cognitive decline seems to be associated with decreasing financial performance, it is thus highly recommended to conduct more longitudinal research in order to enable further investigation of this association.

A second limitation concerns the high level of variability between the studies. The included studies differ greatly regarding sample characteristics, financial performance assessments, and statistical analyses used (see Tables 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7), complicating their comparability for the present review. One of the factors that may particularly contribute to the heterogeneity between studies is that the diagnostic criteria of the included neurodegenerative diseases have evolved over time. One of the more impactful changes being that the diagnostic criteria for dementia in the DSM IV-TR have been adapted to include criteria for minor and major neurocognitive disorders in the DSM-5, which was published in 2013 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); criteria that largely correspond to the criteria for MCI and dementia, respectively. As the publication dates of the included studies range from 2003 to 2020, such adaptations in the diagnostic criteria may have influenced the results.

A third limitation on review level is that, based on the chosen keywords and inclusion criteria, not all studies have been identified that focused on IADL, or may have used an IADL item or subscale focused on financial performance. Importantly, the focus of the present review was on assessments of financial performance specifically, rather than IADL measures generally. Furthermore, many of the studies that focus on IADL do not report their outcomes on subscale or item level, but only report a total IADL score instead. In addition, as has been argued above, single items or subscales can be deemed unsuitable to address financial performance in everyday life properly and comprehensively. Moreover, part of the available IADL scales include items that focus on general shopping abilities, which, as discussed before, does not coincide fully with the definition of financial performance. Taking these considerations into account, the present systematic review can and should not be taken as a complete overview of all studies using finance-related IADL items, but rather as an overview of studies specifically addressing financial performance in people living with different neurodegenerative diseases, for which some studies made use of an IADL (sub)scale.

A fourth limitation concerns that none of the included studies formally examined the influence of factors such as ethnicity and cultural background, socioeconomic status, or prior financial experience on self and informant reported financial performance. Some of the included studies did, for example, add race, socioeconomic status, or income level as a demographic characteristic to their study, but none of the studies subsequently addressed associations between these kinds of variables and the assessment of financial performance. As factors like ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or financial experience seem to be of clear relevance to the level of financial performance of an individual, it is recommended future studies take these factors into account when examining the financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative disease.

Finally, it needs to be acknowledged that the present review has focused on self and informant reports of financial performance, which are known to be susceptible to bias (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Indeed, both the self and informant reports considered in this systematic review could potentially be over or underestimations of the actual financial performance of people living with neurodegenerative diseases. Further, discrepancies may exist between self and informant reports of financial performance, which have been suggested to be due to reduced insight of people living with neurodegenerative diseases into their financial abilities (Gerstenecker et al., 2019). It should be stressed, however, that the aim of the present review was to specifically identify what kind of problems in financial performance are reported for/by people living with neurodegenerative diseases, and to, in this way, complement rather than substitute the outcomes on performance-based financial tasks. While objective, performance-based financial tasks may form an adequate measure of financial competence and are less susceptible to bias, subjective assessments appear to be more suitable measures for the everyday financial performance of an individual or group (see Table 1). Future research should thus aim to combine both objective and subjective measures to gain further insight into the financial capability of people living with neurodegenerative diseases.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review indicates that people living with neurodegenerative diseases are more vulnerable to impairments in financial performance than cognitively normal individuals. Furthermore, financial performance appears sensitive to relatively mild impairments in cognition. In line with the findings on the performance of people living with neurodegenerative disease on objective financial competence tasks (Bangma et al., 2021), the degree of self or informant reported problems in financial performance seems to be related to the severity of cognitive decline. As the vast majority of studies addressed financial performance in people living with MCI or people living with AD, more research is, however, needed to investigate financial performance in other neurodegenerative diseases. Further, associations between financial performance and demographic variables, global cognition, and specific cognitive functions still need to be established and should be systematically evaluated by future research. A substantial limitation of the small number of studies that report on financial performance outcomes in people living with neurodegenerative diseases (k = 22) is that the majority seems to assess financial performance with a single item or subscale. As financial performance constitutes a broad and multidimensional construct, these methods of assessment cannot fully comprise the problems in financial performance people living with neurodegenerative diseases might experience. Moreover, these methods do not allow for the evaluation of their relative strengths in financial performance. In order to avert adverse personal and legal consequences, identify the required type and level of support, and preserve autonomy in those domains of financial performance that are intact still, it is thus recommended that more comprehensive assessments for financial performance (e.g., detailed questionnaires or interviews) are developed and adopted. Specifically in combination with performance-based assessments of financial competence, these self or informant report assessments can offer valuable information about the strengths and weaknesses in financial capability of people living with neurodegenerative diseases.

Appendix 1; Overview and Clarification of Chosen Keywords

Clarification of Chosen Keywords

Primary Keywords

The primary keywords of this review (i.e., all keywords related to neurodegenerative diseases; see Table 9) are broadly consistent with the primary keywords used in the aforementioned review by Bangma et al. (2021) and were selected based on the prevalence rates of the diseases. Therefore, rarer neurodegenerative diseases, such as Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease or corticobasal degeneration, were not included as keywords. Since it goes beyond the scope of the present review to elaborate on the different neurodegenerative diseases, only a short description of the neurodegenerative diseases that were considered as keywords for this review will be provided here.

With prevalence rates increasing markedly with age, AD is the leading cause of dementia and the most common neurodegenerative disease (Qiu et al., 2009). AD is characterised by an insidious onset and gradual cognitive decline that typically starts with impairments in memory and learning, but can concern various cognitive domains, inevitably leading to a progressive loss of functional independence (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Representing a (transitional) state of cognitive functioning between the changes associated with normal aging and dementia, MCI is often considered a prodromal stage of AD related dementia (or other types of dementia) and was, for this reason, also considered in the present review. The diagnostic criteria of MCI generally include a subjective concern about a decline in cognition, an objective impairment in one or more cognitive domain, the preservation of independence in functional activities, and cognitive impairments being sufficiently mild for the person not to be diagnosed with dementia (Albert et al., 2011; Grundman et al., 2004; Petersen, 2004; Petersen et al., 1999, 2001).

After AD, PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease (de Lau & Breteler, 2006). Whilst the clinical diagnosis of PD is based on the associated motor-symptoms (i.e., bradykinesia, resting tremor and rigidity), non-motor symptoms, including cognitive impairments in the domains of attention and executive functioning, memory, and visuospatial functions (Kehagia et al., 2010), are often also present in people living with PD (Kouli et al., 2018). The cognitive deficits associated with PD are common even in the early disease stages (Pfeiffer et al., 2014) and can, with progression of the disease, result in PDD (Hely et al., 2005; Williams-Gray et al., 2013).