At first glance, the position of women in academia has improved considerably over the past 30 years or so: the number of female students enrolled in many highly ranked undergraduate and graduate programs has significantly outpaced that of male students. There are considerably more female faculty members. The #MeToo movement has brought renewed attention to the issue of sexual harassment and sex- and gender-based violence. Nevertheless, despite all these accomplishments, women still face significant barriers inside and outside academia. In Reference Criado Perez2019, Caroline Criado Perez published her book Invisible Women, in which she argues that the entire world is designed based on the needs, preferences, physical anatomy, travel patterns, and basic gender characteristics of men. She identifies the “gender data gap” as the key reason for this: the omission of women from many aspects of data collection and research has essentially led to a lack of accounting for female differences in vast realms of life. In the places where these differences have been acknowledged, they have often been recognized only as “divergences” from the “norm”—in other words, the male. This means that in much of human life, women are characterized as “outside the norm.” Norms are inherent guiding principles of institutions, and they are notoriously slow to change (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010). Men have shaped and dominated most institutions for centuries, many since their inception, leading to a level of institutional blindness regarding women’s work patterns, habits, and needs.

In this article, I examine the gendered nature of political science departments within colleges and universities in the United States. Conceptually, the article builds on feminist institutionalism. Specifically, it examines the broad institutional norms, formal and informal, that define political science departments within their larger institutions, as well as potential avenues for change. In doing so, the article tests specific concepts from feminist institutionalism, such as critical actors (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) and critical mass, as ways of bringing about positive institutional change. It also explores the institutional mechanisms that hamper such change and cause institutions to fall back into the “old ways” (Kenney Reference Kenney1996; Leach and Lowndes Reference Leach and Lowndes2007; Mackay Reference Mackay2014). To that end, I conducted a survey among 1,273 female PhD students and faculty members in political science departments across the United States. The survey questions revolve around women’s perceptions of institutional gender norms, the way they are judged by them, their ability to have professional success under them, and their (or others’) ability to change them.

In terms of institutional change, my operating assumption is that a critical mass of women in any department and at critical ranks in the university administration should mean positive changes in institutional gender norms. However, this article also considers the possibility that critical actors (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) may be more successful in bringing about positive gendered changes within both universities and political science departments.

After discussing the survey results within the context of feminist institutional theory, I offer some conclusions about the positions of women in political science departments in the United States, the implications of this for the profession at-large, and some thoughts on avenues for future research on the issue.

Based on the results of my survey, I find that a critical mass of women is necessary but not sufficient to bring about such positive gendered change. While women provide important new impulses and perspectives for institutions to change their gendered norms, their presence alone cannot bring about enough profound normative change. Critical actors in key positions of power within the institution are needed in addition to a critical mass of women to bring about meaningful change. However, I caution that it is crucially important to open up institutions to the perspectives and challenges of women of color. While women of all ethnic and racial backgrounds remain underrepresented in political science, women of color face particularly tough challenges. A more intersectional approach is needed to elevate and consider their particular experiences and the specific challenges they face in the field. Research fields that are built predominantly on the perspectives and contributions of white people cannot possibly make generalizable claims.

Feminist Institutionalism and the Academy

Prior work in feminist institutionalism provides the theoretical foundation for my research. Institutions such as universities are inherently, by means of their organizational structure, gendered to the disadvantage of women. Acker (Reference Acker1990, Reference Acker1992) notes that gendered organizations revolve around four dimensions: a gendered division of labor, gendered interactions, gendered symbols, and gendered interpretations of anyone’s position in the institution. Organizational structures and institutional norms tend to stand in the way of women’s career aspirations while simultaneously reproducing male dominance within the same settings.

If we assume that educational institutions are structured based on gender, and around the needs, work routines, and habits of men, we need to first understand how institutions and their underlying norms evolve in the first place. Sociological institutionalists have argued that institutions evolve around the needs and perceptions of the actors within them (DiMaggio and Powell Reference DiMaggio, Powell, DiMaggio and Powell1991). Thelen (Reference Thelen1999, 386) notes that institutions “are collective outcomes” and “socially constructed in the sense that they embody shared cultural understandings.” In other words, institutions are the product of social interactions and some level of normative consensus.

Institutions also maintain, by design, a certain level of stability and path dependence (Mahoney and Thelen Reference Mahoney, Thelen, Mahoney and Thelen2010). Kingdon (Reference Kingdon1984) describes institutional change mostly as the result of incrementalism: as criticism of and attention to institutional practices grow in certain areas, pressure for change increases incrementally until a tipping point is reached and change occurs. In some special cases, however, sudden exogenous events can lead to a “punctuated equilibrium” in which institutional change is sudden and violent (Kingdon Reference Kingdon1984). Those who benefit from institutional arrangements and institutional norms have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo, and they use their institutional power to mobilize support for doing so (see Streeck and Thelen Reference Streek, Thelen, Streek and Thelen2005).

Feminist institutionalists have long attempted to draw attention to the embeddedness of gender in institutional norms and power relations (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010). For instance, Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010, 580) point out that gender underlies social relationships “based upon perceived (socially constructed and culturally variable) differences between women and men, and as a primary way of signifying (and naturalizing) relationships of power and hierarchy.” In a “gendered institution,” according to these authors, these notions of what it means to be feminine and masculine are deeply embedded in its regular operations. Furthermore, access to resources and power tends to be deeply gendered, as are norms of “acceptable behavior” (Chappell Reference Chappell2006; Duerst-Lahti and Kelly 1995). Importantly, feminist institutionalists have pointed out that many norms of behavior that are framed as “neutral” in fact embody typically male characteristics and make certain assumptions about male patterns of working behavior, domestic support, and so on (Chappell Reference Chappell2006). This “gendered neutrality” can seriously disadvantage women in terms of their salary and opportunities for promotion, as they are evaluated based on highly gendered assumptions of what constitutes appropriate work. Likewise, institutional norms may also commend what is considered “appropriate behavior” for men and women who work within institutions (Chappell Reference Chappell2006). Institutions, therefore, operate based on gender norms, but in doing so, they also reproduce gendered expectations of “appropriate behavior” over and over again.

Feminist institutionalists, however, do not rule out possibilities for institutional change. Thompson (Reference Thomson2018) addresses the possibility of positive gendered change in institutions through critical actors (see also Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009). As has been established, institutional change is mostly slow and incremental (save for a disruptive event that would create a “punctuated equilibrium”), but not impossible. Instead of arguing for a critical mass of women represented within any given institution, Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2009) point to critical actors who promote positive change around women’s issues as crucially important for institutional reform. Critical mass theory, they note, makes specific and somewhat questionable assumptions about the behavior of women and men as actors within institutions, merely based on their gender. In other words, if we cannot predict the behavior of all actors within an institution based on their gender, we cannot not know whether descriptive representation of women will also lead to substantive representation and necessary reform (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009, 145). Critical actors, on the other hand, are institutional actors who (regardless of their gender identity) under specific circumstances, in particular contexts, in a special position can make positive institutional change happen.

Even if the formal rules of institutions can be changed to better incorporate and benefit women, institutions may exhibit path dependence in spite of institutional change, as even “new institutions are inevitably informed by ‘legacies of the past’” (Mackay Reference Mackay2014, 552). Mackay uses the term “nested newness” to explain the way in which institutional change is still nested within an institutional history, time, and place. In other words, institutional change does not happen in a vacuum, but it is profoundly impacted by what was there before: the legacy of norms, habits, and behaviors adds to the complexity (and difficulty) of implementing and sustaining institutional reforms in the long term. This can play out either in the form of institutions falling back into old ways and regressing after reforms, or in informal rules and arrangements that may contradict or undermine the reform of formal institutional rules (Kenney Reference Kenney1996; Leach and Lowndes Reference Leach and Lowndes2007; Mackay Reference Mackay2014).

While most of the work on feminist institutionalism revolves around institutions of government—the government bureaucracy as well as the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches—my research focuses on academic institutions, and specifically political science departments. Academic institutions are important generators of research that can also inform policy decisions; educators can also act as important role models for future generations. Moreover, academic institutions in the United States display many of the same patterns that can be observed in the political realm. Women, on average, have less access to networks and professional insider information within departments and the discipline (Kantola Reference Kantola2008; Smith and Calasanti Reference Smith and Calasanti2005), and women’s assigned roles within a department often fall into norms of masculinity and femininity as described by feminist institutionalist scholars. Several researchers have noted that women’s involvement in teaching and service work also reflects what women see as their mission within the institution: a commitment to mentoring students and advancing causes of diversity and equity can be a way to improve academia for women and minorities (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Pifen, Humphrey and Hazelwood2011; Griffin and Reddick Reference Griffin and Reddick2011; Kantola Reference Kantola2008; O’Meara et al. Reference O’Meara, Kuvaeva, Nyunt, Waugaman and Jackson2017; Stanley Reference Stanley2006; Turner Reference Turner2002). Tierney and Bensimon (Reference Tierney and Bensimon1996) suggest that teaching and service work helps women feel more visible and connected in an environment where they still experience significant levels of sexism.

This shows that it is not just the “rules of appropriateness” (Chappell Reference Chappell2006) within institutions that shape their order and inner workings, but that institutional norms and operations are also shaped by the way that marginalized actors cope with gendered norms and their embedded “logic of appropriateness.” Women’s work decisions are essentially a function of gendered organizations and institutional cultures and not purely a function of “gendered choices.” Women tend to be invited to engage in more service and teaching activities (as opposed to research), to increase committee diversity, because they are “typecast” to be reliable and committed teachers and administrators (Cross and Madson Reference Cross and Madson1997; Padilla Reference Padilla1994; Tierney and Bensimon Reference Tierney and Bensimon1996; Turner Reference Turner2002).

Research work, on the other hand, remains the most important factor in determining success in hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions in political science departments. Frances (Reference Frances2018) finds significant salary gaps between men and women in academia, which grow over time. Several studies have shown that women have fewer overall publications than men, even at comparable career levels (Mitchell and Hesli Reference Mitchell and Hesli2013; Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017). The top 10 journals publish proportionately fewer articles authored by women, compared with the proportion of women in the discipline as a whole (Teele and Thelen Reference Teele and Thelen2017). Even though around 40% of new PhDs and 27% of tenure-track faculty within the largest PhD-granting programs are women, only 18% of the articles published in the American Journal of Political Science and 23% of the articles published in the American Political Science Review were written by women. Teele and Thelen (Reference Teele and Thelen2017) found that only two of the top 10 journals in the discipline published work by women proportionate to their representation: Political Theory and Perspectives on Politics, where 34% of all articles were authored by women, respectively. The authors explain that a majority of the flagship journals in political science (except Political Theory and Perspectives on Politics) are heavily quantitative journals, and women have published a larger share of the qualitative work in the field over the past 15 years.

Koivu and Hinze (Reference Koivu and Hinze2017) suggest that women and minorities face more strenuous constraints in terms of research budgets and time—a function of their severe underrepresentation in the higher ranks of the profession. They also note that “methodological rigor is determined by those groups most strongly represented in the field, who have more resources at their disposal” (Koivu and Hinze Reference Koivu and Hinze2017, 1026).

Finally, motherhood appears to make a difference in women’s professional upward mobility within the discipline. Women around the world provide disproportionately more caregiving than men. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, women spend an average of 4.5 hours a day on unpaid care work, more than twice as much as men (OECD 2014). When childcare facilities and schools close down (as they did during the COVID-19 pandemic), when someone in the family gets sick or requires care, women tend to be the ones to remain in the home and provide the caregiving (often on top of their regular work hours) (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020). Care work is notoriously undervalued, which some researchers have attributed to the fact that it remains largely invisible and is mostly performed by women (who self-promote less and whose work is generally valued less than that of men) (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020). Yet simultaneously, such care work is crucially important: the daily work that (mostly) women engage in, such as household labor and physical and emotional care, is critical to what Laslett and Brenner (Reference Laslett and Brenner1989, 383) call “social reproduction”—the rearing and socialization of the coming generation. Without such care work, they argue, our society could not function properly. Because women provide the bulk of this crucial (yet invisible) care work, they tend to work longer total hours than men, do more unpaid labor (ILO 2018; Sayer Reference Sayer2005), are more likely than men to be single parents and provide for more dependents on a single income (Cohen Reference Cohen2010). The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated all these existing gender-based inequities in providing care work. It also put women at higher risk of losing their job (especially when no paid leave was available to them). Pandemic lockdowns caused women to be more likely to experience domestic violence and lose access to reproductive care (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020).

Childbearing and child-rearing have a negative impact on women’s careers in academia, whereas fatherhood has a net positive effect (Ginther and Hayes Reference Ginther and Hayes2003; Ginther and Kahn Reference Ginther and Kahn2004; Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012). Another study found that female faculty members are less likely to be married and have children than male faculty members (Acker and Armenti Reference Acker and Armenti2004). Morrison, Rudd, and Nerad (Reference Morrison, Rudd and Nerad2011, 545) found that male faculty members have higher odds of receiving tenure if they are married to a spouse without a professional degree. Chappell (Reference Chappell2006, 228) writes about the gendered perceptions inherent in supposedly “neutral” labor standards:

The meritorious ideal public servant is a rational, detached, calculating individual, while the desired attributes for appointment to the career service include a full-time unbroken work record, as well as the assumption of full-time domestic support. (emphasis added)

This is as true for academic institutions as it is for the government bureaucracies that Chappell describes: maternity leave and the demands of child-rearing tend to mean the opposite of an “unbroken work record,” and the vast majority of women in academia raise their children without “full-time domestic support.” These realities clash with the gendered norms that are inherent in labor expectations within academia (and most other employers as well).

Chappell (Reference Chappell2006, 228) notes that gendered perceptions of bureaucratic labor lead not only to lower chances of promotion for women, but also to their chronic “absence at senior levels of the bureaucracy,” resulting, in turn, in the further institutionalization of gendered norms:

Without women’s input, … decisions that are made at the highest level have tended to disregard (and thereby reinforce) the unequal political, economic, and social position of the two sexes, as well as make stereotypical assumptions about male and female behavior.

While this article focuses on gender, it is important to note the intersectional nature of race and ethnicity in this context. People of color remain most underrepresented in the discipline. The American Political Science Association’s (APSA’s) Project on Women and Minorities (P-WAM) documents these disparities. According to the most recent data from the 2018–19 academic year, 75% of political science faculty (tenured, tenure track, and non-tenure track) in the country’s 100 highest-ranking academic institutions were white, 7.7% Asian, 4% Latin American/Hispanic, and 3.9% African American/Black. This means that the ethnic and racial composition of political science departments across the country is still not representative of the student population (let alone the population as a whole!), where student Black/African American students averaged 7.2%, Latin American/Hispanic students 17.5%, Asian students 10.2%, and white students 57.6% during the 2017–18 academic year (APSA 2019). The underrepresentation of faculty of color leads to myriad issues for students and incoming faculty of color: on average, faculty of color receive less research funding (Hoppe et al. Reference Hoppe, Litovitz, Willis, Meseroll, Perkins, Hutchins, Davis, Lauer, Valantine, Anderson and Santagelo2019), see fewer of their articles published in high-ranking academic journals (Roberts et al. Reference Roberts, Bareket-Shavit, Dollins, Goldie and Mortenson2020), are less likely to be cited (Chakravarty et al. Reference Chakravarty, Kuo, Grubbs and McIlwain2018), and receive less favorable ratings on student evaluations when teaching the same materials and giving the same assignments as white male colleagues (Chavez and Mitchell Reference Chavez and Kristina2019). During the 2021 calendar year, a number of prominent female professors of color left their institutions, citing racism and lack of institutional support for promotion and tenure (Flaherty Reference Flaherty2021).

APSA’s McClain Task Force on Systemic Inequality in the Discipline provides additional insights with its research on systemic inequities in areas like promotion and tenure, citations, general institutional climate, and graduate training. Published in 2022, the task force’s research examines race-, gender-, sex-, and ethnicity-based (among other factors) inequities, from disparate treatment to harassment in the discipline. In terms of tenure and promotion experiences, researchers found that people of color confront systematic hostilities in the tenure and promotion process, which makes mentorship by colleagues even more key for their success. In terms of general climate in the discipline, the McClain Task Force uncovered significant levels of discrimination that people of color, ethnic and national minorities, and women confront in the discipline, including conferences, but also within their respective departments. In terms of departmental climate, some of the task force’s top findings were

pervasive examples of anti-Semitism, anti-Black bias, anti-Asian bias, other forms of racism, sexism and misogyny ranging from comments about women’s attire to grade deflation as retaliation against non-reciprocity of sexual advances, verbal hostility (usually, but not always, from male faculty members) ranging from snide and sarcastic remarks to talking over someone, browbeating, and outright yelling, senior colleagues demeaning and berating junior colleagues, unsubstantiated accusations and harassment. (APSA 2022, 16)

The findings underscore not only that the climate in many political science departments (and the discipline as a whole) is often outright hostile to faculty of color and women, but also that academic hierarchies in terms of rank still matter greatly.

Since one’s publications and the amount of attention those publications receive are among the most significant ways for PhD students and faculty members to be successful in securing academic jobs, tenure, and promotion, the McClain Task Force also examined citation patterns. The researchers shed light on the highly intersectional effects on citation patterns: gender (women are significantly less likely to be cited than men), race (Black and Hispanic researchers were significantly less likely to be cited—though the effects of identifying as Hispanic was not statistically significant—while identifying as white or Asian was associated with a greater number of citations), as well as employment at an R1 university (being employed at an R1 was associated with a higher number of citations), and recency of one’s PhD (recency was associated with a lower number of citations) (APSA 2022, 39). These findings underscore the importance of intersectionality in considering inequities across all areas of the discipline. They also emphasize that it is important to consider the compounding effects of gender, race, ethnicity, and status within the discipline. Solutions that target gender in a vacuum are insufficient to address the larger issues of inequity in the discipline.

These systemic inequities in political science also affect students. A recent study of political science PhD students found that Black students, as well as students of Middle Eastern or North African descent had less trust in their quantitative methodological skills compared with white students (Smith, Gillooly, and Hardt Reference Smith, Gillooly and Hardt2022). More importantly, the same study showed that gender disparities in confidence in one’s skills were more pronounced among students of color, and racial and ethnic gaps in confidence were starker among women compared to men (Smith, Gillooly, and Hardt Reference Smith, Gillooly and Hardt2022). This implies that race, ethnicity, and gender have a compounding effect on research support and subsequently confidence in one’s own efficacy as early as graduate school,Footnote 1 which has devastating implications for the future academic success of women of color.

It is important to acknowledge the intersectional nature of discrimination within the discipline. Further studies are needed to understand the full extent of this issue. However, the data and the limited number of studies available demonstrate that universities in general and political science departments in particular remain path dependent: the chronic underrepresentation of women and people of color leads to research, teaching, and service standards for appointment, tenure, and promotion decisions, as well as a general institutional culture that are based on the research interests, teaching style, service expectations and general standards of behavior of cisgender white men.

In this article, I examine women’s perceptions of and experiences with institutional norms in political science departments and the institutions. I argue that a critical mass of women in academic departments and the presence of critical actors in departmental and university leadership positions who are sympathetic to advancing the representation and equal treatment of women and powerful enough to implement change can bring about institutional reforms. After discussing the survey results within the context of feminist institutional theory, I offer some conclusions about the positions of women in political science departments in the United States, the implications of this for the profession at-large, and some thoughts on avenues for future research on the issue.

Methodology

During the spring of 2020, I conducted an online survey of all female-identifying tenured and tenure-track faculty members and PhD students and candidates in political science departments across the United States.

A Google search for four-year colleges and universities (including those that grant postgraduate degrees) in the United States yielded a total of 869 institutions with political science faculty (either in a separate department or as part of a composite department of political science and public policy, political science and history, political science and economics, arts and letters, etc.). Of those 869 institutions with political science faculty, 83 (9.5%) did not have any female or female-identifying faculty at all. For the remaining 786 institutions with female political science faculty, I searched the department websites for email addresses of all female or female-identifying faculty. I determined gender identification by name when possible. When this was not possible, I conducted an internet search for each person to help determine their gender identification. When this was not possible either, I included them in the sample. I then added a question about gender identification for all respondents to my survey that allowed them to identify their choice. Since this research was specifically about women and female-identifying people, only respondents who identified as women (regardless of gender assigned at birth) were directed to answer the rest of the survey questions.

I chose to include only women and female-identifying people in the sample because, for the purposes of this study, I was particularly invested in providing a female lens through which to view the institutional norms and culture underlying political science departments and their respective academic institutions. Much of the feminist institutionalist literature introduced in this article points to the deeply gendered nature of institutional norms. Moreover, feminist institutionalist scholars have critiqued the broader field of institutionalism for its gender blindness (see, e.g., Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010). Only through the lens of feminist institutionalism have scholars been able to identify the gendered nature of assumptions, institutions, and labor generally assumed to be neutral. In other words, women may be able to better identify the gendered nature of institutional norms and culture that have long been perceived as neutral. As Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010, 582) note, “the masculine ideal underpins institutional structures, practices and norms … constraining the expression and articulation of marginalized perspectives.” By focusing my survey on women and people who identify as female, I hope to capture one of those marginalized perspectives.

Throughout the 2019 fall semester, my search for email addresses generated a total of 4,811 email addresses of female or female-identifying tenured and tenure-track faculty and PhD students and candidates. I distributed the survey via Qualtrics on April 6, 2020, to all 4,811 email addresses and kept it open until July 6, 2020. During that time, the survey yielded 1,273 responses, a response rate of 26.5%. For a survey in which respondents were not part of a panel, this is an exceptionally high response rate. Even though this cannot eliminate the possibility of nonresponse bias in the sample, it increases the chance that my sample is highly representative of the target population.Footnote 2 All survey responses were anonymous, and any identifying data, such as IP addresses, were immediately removed from the data.

My survey included closed and open-ended questions (“why do you feel this way?”). The survey questions provided a bigger picture and an actual estimate of incidence regarding the general perceptions of women in political science departments across the country. The open-ended questions provided the opportunity to dive deeper and get specific insights into the respondents’ feelings and rationale for their survey responses. The first few questions were demographic questions about the respondent’s identity and their institution and position. The remaining questions focused on the role of gender in career opportunities, such as tenure and promotion; the availability family leave for faculty and students; the possible impact of motherhood on the respondents’ careers; the respondents’ perceptions of the institutional culture of the institution and their departments; and the respondents’ perceptions of the fairness of student evaluations of women (compared with men). One question also addressed the respondents’ thoughts on how the COVID-19 pandemic (and caregiving and homeschooling in particular) affected women’s work lives.

I ran simple crosstabulations on the responses with the respondents’ position (student, assistant/associate/full professor) and the kind of institution (R1/non-R1/PhD-granting/non-PhD-grantingFootnote 3) as independent variables. Any differences noted are statistically significant. I also ran some basic predictive statistical models on the data, but they did not add any significant information to the descriptive statistics.Footnote 4

Findings

Who Were the Respondents?

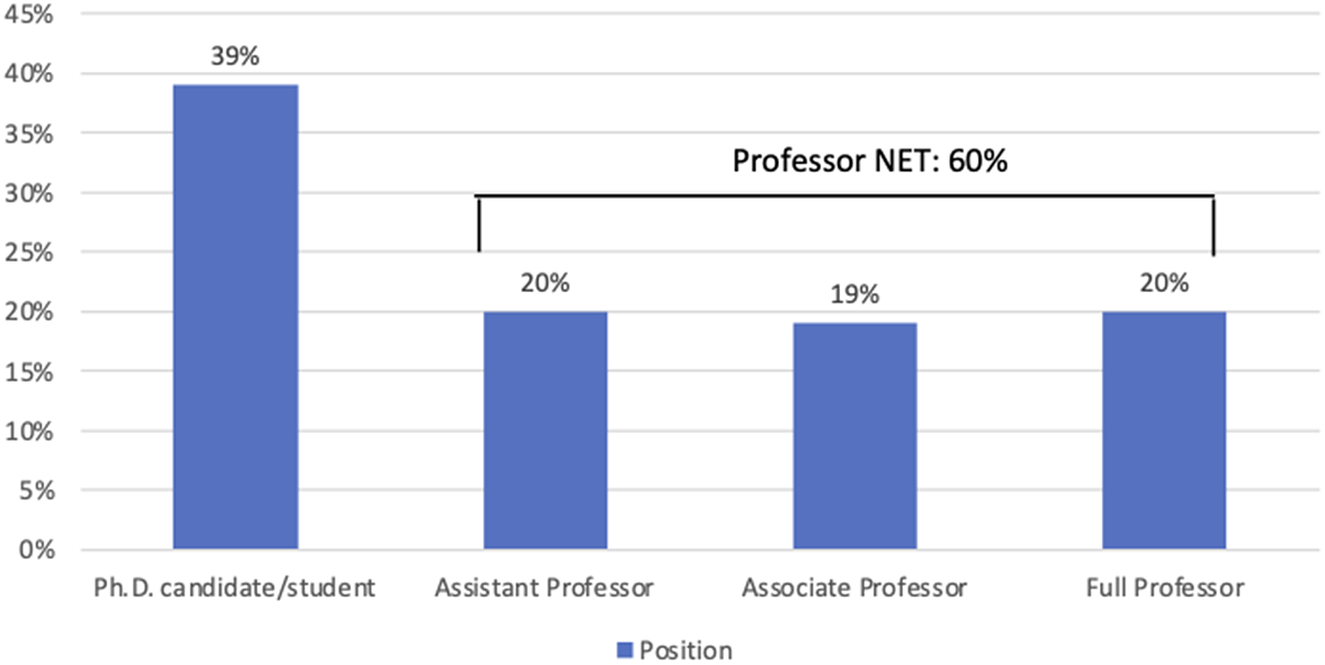

Of the 1,273 respondents, 39% were PhD students, 20% were assistant professors on the tenure track, 19% were tenured associate professors, and 20% were full professors (Figure 1).Footnote 5

Figure 1. Respondents by position.

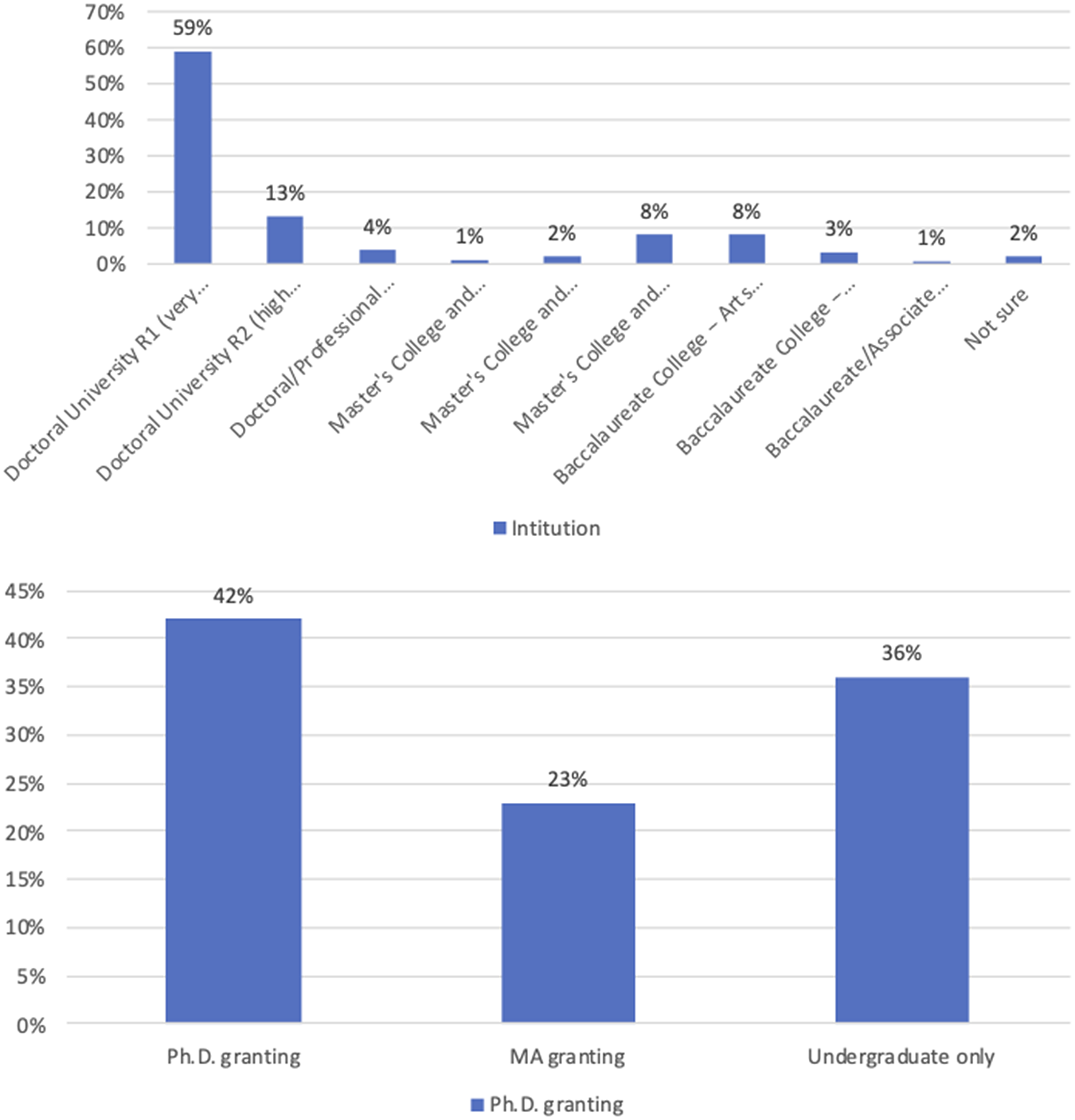

As shown in Figures 2a and 2b, a plurality of respondents were working in a PhD-granting department, and a majority were employed at an R1 doctoral university with very high research activity.

Figure 2. (a) Type of university. (b) Department type.

Departmental and Institutional Inclusiveness

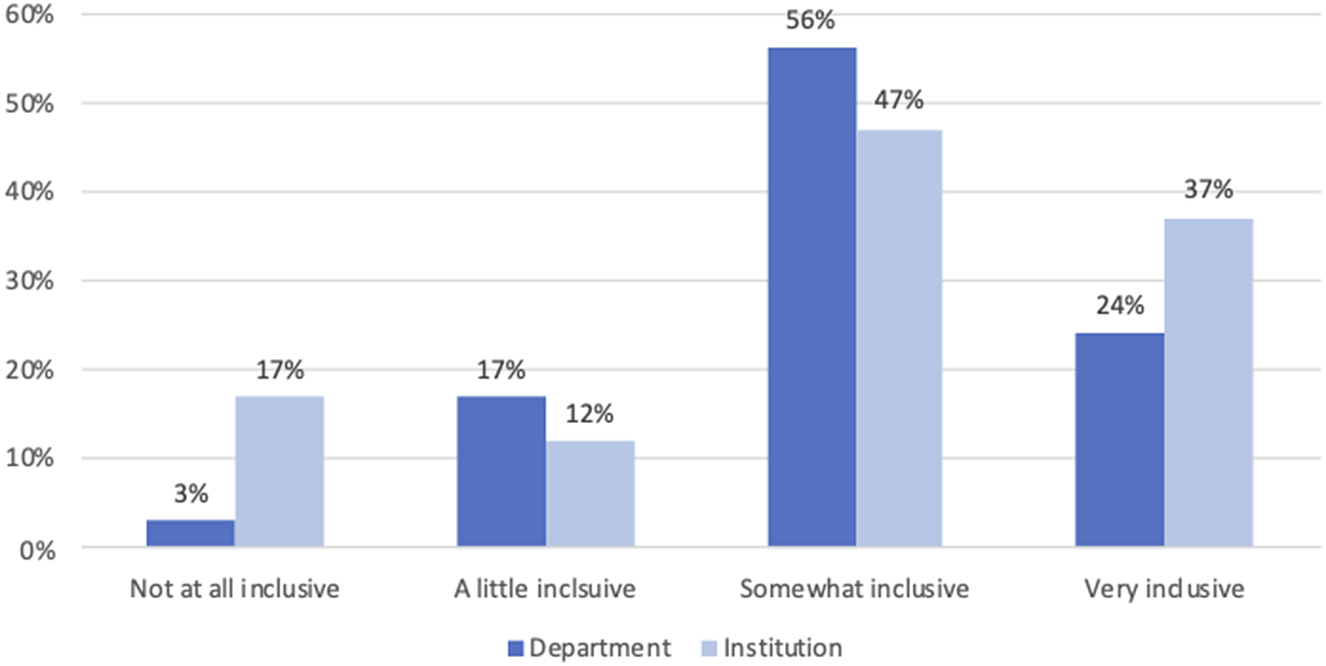

Overall, respondents rated their departments and institutions as overwhelmingly inclusive, with home departments scoring significantly higher than the university as a whole. As shown in Figure 3, departments were rated as “very inclusive” by 13 percentage points more than institutions (24% of respondents rated their institutions as “very inclusive,” while 37% of respondents rated their departments as “very inclusive”).

Figure 3. Inclusiveness of institutional culture.

Figure 3 shows that the majority of respondents saw their department as “somewhat inclusive” or “very inclusive.” Those trends were replicated for respondents’ feelings about their respective institutions, but all respondents felt considerably less confident in the inclusiveness of their institutions, compared with their departments. This trend held across ranks and tenure versus pre-tenure.

A specific question on gender and departmental standing provided important additional insights. When asked about the effects of their gender on their standing in the department, 43% of respondents perceived their gender to have a net negative effect on their standing in the department, and only 16% found their gender to have a net positive effect (with 41% saying that their gender had no effect at all on their standing in the department).

Comparisons across groups, again, add important nuance. Pre-tenure faculty found their gender to affect their standing in the department less negatively than tenured faculty: 34% of pre-tenure faculty thought their gender was affecting their standing in the department negatively, whereas 45% of tenured faculty thought so—a difference of more than 10 points (p = .005). Institution type seemed to affect perceptions as well: 49% of women in PhD-granting institutions found their gender to have a negative effect on their standing, whereas 36% of women in non-PhD-granting departments thought so (p = .001). Similarly, 46% of women at R1 institutions found their gender to have a negative effect on their standing, whereas only 38% of women at non-R1 institutions thought so (p < .0001).

Women seemed to have more negative views about inclusiveness of culture and the way their gender affected their department standing if they were further along in their careers and had achieved tenure. This may be the case because after tenure, the service load increases, which provides additional insights into the institutional and departmental culture that respondents may not have had before. These insights (such as sitting through tenure and promotion decisions) may provide specific insights into the gendered nature of any norms of evaluation within the institution and the department. In addition, more research-oriented institutions (and the departments within them) were perceived to be less inclusive by respondents.

The general impression is that departments, even if they are numerically achieving gender parity, are still dominated by a culture that prioritizes cisgender white male perspectives. The “gender parity” and “family friendliness” of departments and universities were often defined by respondents in terms of how many women are on the faculty (i.e., describing a critical mass of women) or how many individuals in the department have families. However, it appears that the majority of women surveyed were junior (and often still untenured) faculty members. The fact that in many political science departments, men overall outrank female faculty maintains a significant power differential between male and non-male faculty.

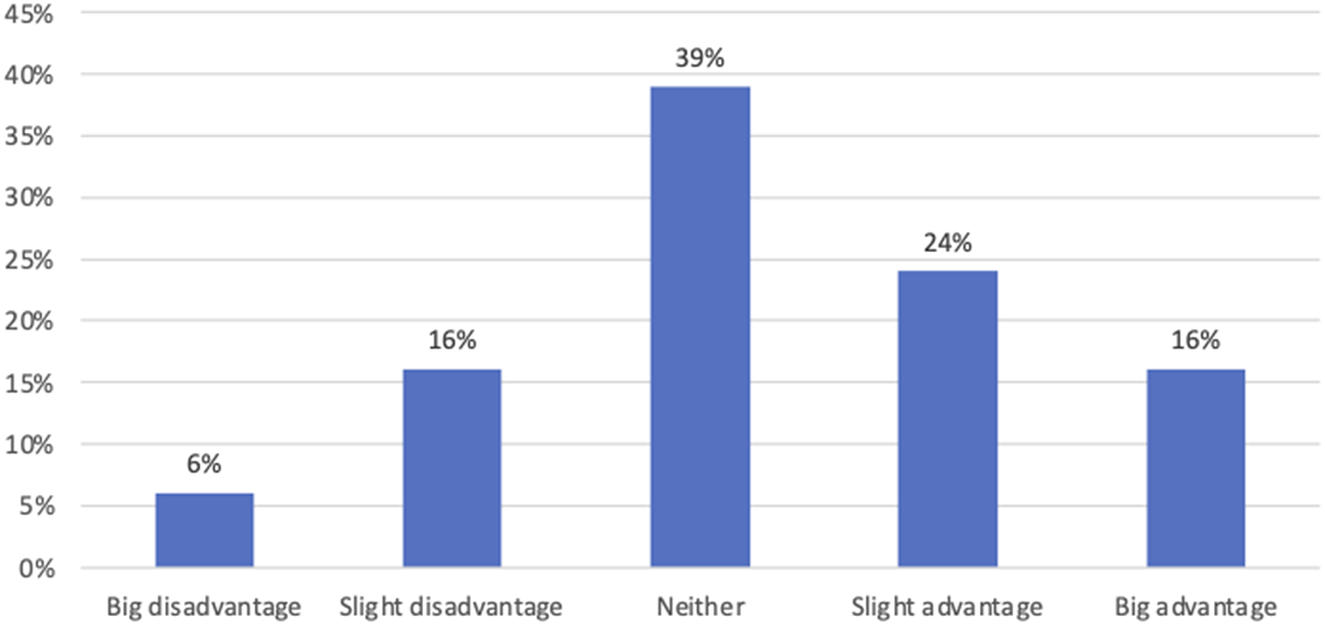

On the question of whether the presence of a larger number of women in the department/university would benefit their careers, respondents remained fairly divided, as shown in Figure 4. However, cross-institutional comparisons reveal some surprising differences among respondents. While, overall, a greater number of women in the department was seen as an advantage by most respondents, the results were less clear when comparing respondents at R1 institutions to respondents at non-R1 institutions. At R1 institutions, 26% of women felt that a greater number of women in the department put them at a disadvantage, whereas only 16% of women at non-R1 institutions felt that way (p < .001). Tenure (or lack thereof) seemed to have a similarly complicating effect on the results. While 49% of pre-tenure women felt that more women in the department provided them with an advantage, only 40% of tenured women felt that way (p = .03).

Figure 4. Gender representation — a benefit for one’s career?

The open-ended responses provide additional clues as to why numerical representation is not a simple answer to improve the workplace for women. Respondents often mentioned that gender parity on the faculty did not guarantee a workplace culture more friendly to junior women faculty and graduate students. In fact, some respondents reported that some female colleagues were just as (or more) hostile than male colleagues vis-à-vis junior (and especially junior non-male) faculty. Still, a plurality felt that more women faculty in the department (especially at the more senior level) would translate into more support for junior women and graduate students in terms of mentorship, protection from hostile behavior by male faculty, better understanding of family demands and the obstacles that women face in the profession, and a softer, more caring climate around the department as such.

This provides some nuanced insights into the question of whether a critical mass of women and female-identifying people or a number of critical actors would be best able to bring about institutional change. The survey results, and especially the responses open-ended questions on that matter seem to imply that both matter to an extent. Gender parity alone seems to be a welcome but not sufficient condition for institutional change to many respondents, whereas critical actors—that is, sympathetic actors in positions of power seem to make a significant difference.

In the open-ended questions, many respondents noted that they carry disproportionate service burdens and that there was less sensitivity toward working mothers (as opposed to working parents more generally) and their juggling of schedules, particularly if they did not have a stay-at-home partner. In addition, many respondents noted that informal networks, especially among faculty, remain “old boys’ clubs,” which involve activities and conversations that women either do not feel welcome or comfortable in participating in. As one respondent remarked,

Male faculty and graduate students socialize in extremely gendered activities including playing poker. As a woman I have either been excluded from these activities or subjected to harassment while participating in them. I am rarely consulted in informal networks and conversations in the department, which is where most consequential decisions have traditionally been made. … I still find it challenging to penetrate the old (and young) boys club in the department, and I constantly push for decisions to be made in the open through formal institutions rather than through secret male-dominated conversations behind the scenes.

This underscores many of the arguments made by feminist institutionalist scholars, who have noted that even if institutions do change to become more gender inclusive, backsliding in institutional culture can often happen through informal channels. Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell (Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010, 583), for instance, point out that “the ways in which male-dominated … elites have shifted the locus of power from formal to informal mechanisms in order to counteract women’s increased access and presence in formal decision-making sites.” My survey responses indicate that as the number of women in departments increases, some male actors may shift to those informal mechanisms to broker decisions and wield influence.

A 2018 APSA-commissioned study found that 30% of women reported to have experienced sexual harassment at APSA meetings between 2013 and 2016 (APSA 2018). Sexual harassment appears to be common in contexts across the discipline and came up in many responses to the open-ended questions. Respondents who had experienced harassment noted that there had generally been few consequences for such behavior: sexual harassment issues appear to be mainly “resolved” through retirement, not through any proactive efforts by the department or the university, which presents a real issue for the many victims of such harassment, as well as an obstacle to institutional change.

Feminist institutionalists have addressed sexual harassment and violence as part of the gendered normative structure underlying most institutions. Raney and Collier (Reference Raney and Collier2022), for instance, see harassment and violence as part of the same logic that Chappell (Reference Chappell2006) describes as the “gendered logic of appropriateness.” Where the normative framework within institutions is already deeply gendered, gender-based violence and harassment further enforce this framework. In fact, some research suggests that male actors may use sexual harassment and violence as means to reinforce gendered power structures when women “intrude” on traditional male territory within deeply gendered institutions (Collier and Raney Reference Collier and Raney2018; Lovenduski Reference Lovenduski2014).

Sexual harassment and violence, therefore, are both a function of gendered institutions and a reinforcer of them, used to put “intruders” in “their place.” The fact that many respondents indicated that sexual harassment tends not to be formally resolved and often remains without consequences for the offenders implies that many departments maintain a deeply gendered normative structure. As Collier and Raney (Reference Collier and Raney2018, 450) note, “institutional rules, procedures, and norms can perpetuate violence against women.” If institutional rules and norms allow sexual violence and harassment to go unsanctioned, they become complicit in violence against women, which goes beyond merely maintaining a gendered institutional culture. Where sexual violence and harassment can become a tool for those traditionally favored by institutional rules and norms—men—to defend against the proliferation of women into higher institutional ranks, they become intrinsically weaponized. Based on my survey results, the weaponization of sex- and gender-based harassment and violence appears to be a not infrequent occurrence. This is among the most disturbing findings in this research and warrants more investigation and action, not just by researchers but also by upper-level administrators.

Intersectionality

In terms of standing at the department level, many respondents identified confounding factors, such as race/ethnicity and motherhood, that led, in their perception, to a more disadvantaged standing. As established earlier in this article, the vast majority of political science departments are overwhelmingly white, and the intersectional perspectives of women of color are particularly underrepresented at the department and university levels. Said one respondent,

I want to be clear that gender has to be tied with race here. I am not an acceptable female [to the men in the department] because I am a woman of color, and even worse, I am young. … Every aspect of my advancement is a battle, and my diversity is an adversity. Also, I don’t think that the few female scholars are supportive either, they promote a problematic agenda that supports a particular form of white feminism.

Women of color in particular reported concerns about their standing in the department. Concerns were related to a variety of issues, among them the lack of inclusiveness of white feminist ideals often advocated by white female colleagues (who are almost always in the majority), the insensitivity and often outright hostility of white males to the challenges faced by women of color, and departments’ affirmative action policies, which are often poorly and insensitively implemented, leading to, as one respondent put it, “female hires not having the same credibility as male hires.” Powell (Reference Powell2018) draws some similar conclusions in her research on affirmative action and other programs to increase gender equity in academia. While affirmative action programs were able to add more women faculty, they did not have any success in changing structures and values. Instead, as Powell (Reference Powell2018, 30) puts it, they “simply added women to an unchanged structure.” In addition, Powell found that affirmative action approaches generally lacked intersectional perspectives, and therefore lack breadth, depth, and inclusivity.

Family and Children

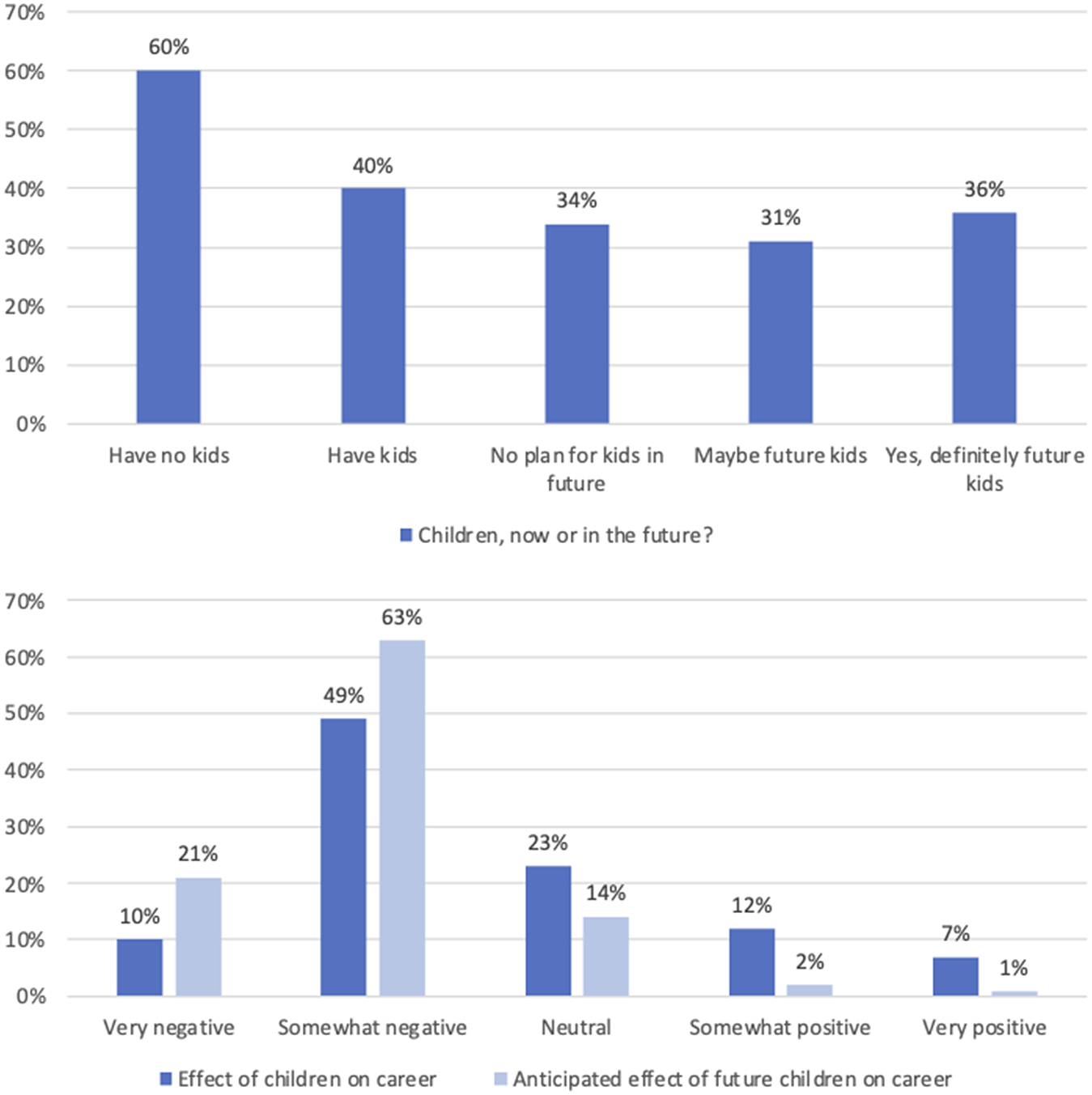

A majority of respondents (59%) who had had children at some point during their careers reported that having children had a net negative effect on their professional advancement (Figures 5a and 5b). On the other hand, 19% thought that parenthood had had a net positive effect on their careers, and 23% saw no effect at all. Those who did not have children at the time the survey was conducted but said that they wanted children in the future were asked what effect they anticipated their future children would have on their careers. Their perceptions were far more negative than the perceptions of respondents who already had children: 83% thought that their future children would have either a very negative or a somewhat negative effect on their careers.

Figure 5. (a) Plans to have children, now or in the future. (b) Perceived or anticipated effects of having children on career.

Previous studies have found that women engage in the bulk of the caregiving: on average, they spent twice as much time as men on unpaid care work (ILO 2018; OECD 2014). In addition, motherhood is met with particular challenges in the academic profession and, in a male-dominated institutional culture, tends to be treated differently than cisgender fatherhood (Ginther and Hayes Reference Ginther and Hayes2003; Ginther and Kahn Reference Ginther and Kahn2004; Hesli, Lee, and Mitchell Reference Hesli, Lee and Mitchell2012).

Mothers were also asked to compare the effect of their gender on their careers to the effect of having children, specifically. Figure 6 shows that a majority (52%) found that motherhood had impacted their careers more negatively than their gender, whereas just 16% thought it had had a more positive effect than their gender.

Figure 6. Career impact of motherhood versus gender.

The sentiment that parenthood affects women’s careers more deeply than gender is reflected in many of the qualitative responses. As one respondent reported,

Despite having a large contingency of feminists (male and especially female), it is routinely made clear to me—even by them—that one should be very careful not to remind anyone that there are children in the equation. Other women in my program are routinely cautioned by faculty not to mention family aspirations. Men in the department who have children or talk about the prospect of family do not appear to face similar biases.

The differential perceptions of the impact of parenthood on men’s and women’s careers again speaks to what Chappell (Reference Chappell2006) describes as the “gendered logic of appropriateness” within institutional settings. Men and women are evaluated differently because the supposedly neutral ideal of a worker, a public servant, a politician, or, in this case, a professor is based on deeply gendered norms of appropriateness, such as “an unbroken work record, as well as the assumption of full-time domestic support” (Chappell Reference Chappell2006, 228). Moreover, it is only men who benefit from the “assumption of full-time domestic support.” A woman who, for instance, became pregnant over the course of her career, or was already a parent when starting a new job, would not be able to benefit from that assumption, even if she did have full-time domestic support.

Women’s disadvantages in achieving tenure and promotion do not seem to solely rest on the gendered norms of appropriateness within academic institutions, but it also appears easier for men to violate those norms without consequence, compared with women. The assumptions inherent in gendered norms tend to bias institutions against women more generally: as Chappell (Reference Chappell2006, 228) writes, “women are considered less deserving of promotion because of their purported irrational nature” and “their historic absence at senior levels … has had a further gendering effect: Without women’s input, … decisions at the highest level have tended to disregard … the unequal … position of the two sexes, as well as make stereotypical assumptions about male and female behavior.”

Student Evaluations

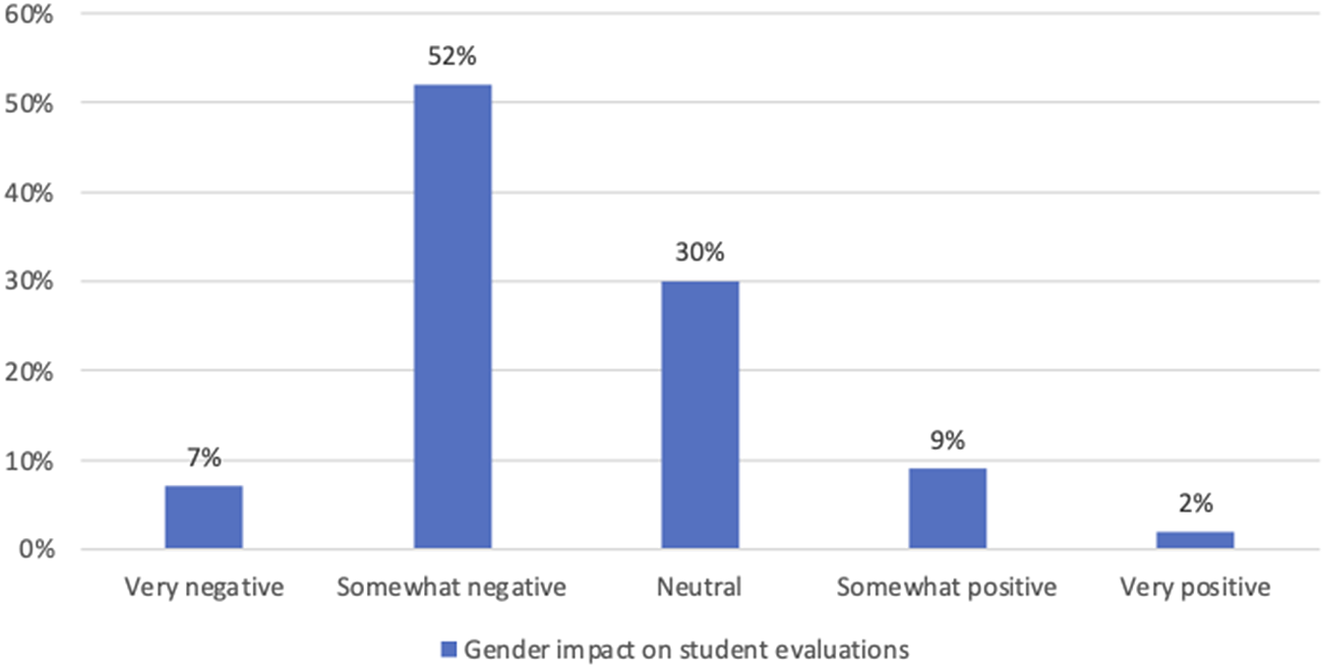

Even though student evaluations have recently come under some criticism, partly as a result of Chavez and Mitchell’s (Reference Chavez and Kristina2019) pathbreaking study about the bias in student evaluations in political science, they are still used quite widely to assess teaching quality in tenure and promotion decisions. Yet the growing skepticism about student evaluations is reflected in the responses of women in political science. As displayed in Figure 7, 59% of survey respondents said that their gender had a net negative effect on their student evaluations, and 11% thought their gender had a net positive effect on student evaluations (30% felt the effect was neutral).

Figure 7. Perceived gender impact on student evaluations.

Comparisons among different groups, once again, allow for a more nuanced picture. Institution type seemed to make a big difference in women’s perceptions. At R1 institutions, 63% of women thought that their gender had a net negative impact on student evaluations, whereas 53% thought so at non-R1 institutions (p = .001).

In the open-ended responses, some respondents also noted that their evaluations were generally good or even better than those of their male peers. Others felt that they received consistently worse ratings on student evaluations compared with their male peers and that race and gender are compounding, intersectional factors, leading to even more disadvantage on student evaluations (and general student disrespect) for women of color. Many respondents reported discriminatory language, such as being explicitly called the “b-word” in student evaluations for being strict graders. They also noted that they were often evaluated based on their appearance, their clothes, and whether they were “nice” and “sweet.” This is in line with prior research (Eckes Reference Eckes2002; Ridgeway Reference Ridgeway2001) showing that female instructors are more often rated based on emotional characteristics, such as “niceness” and “approachability,” and less so on others that are more relevant to teaching, such as “intelligence” or “expertise.” Men, on the other hand, tend to get rated based on the latter rather than the former characteristics.

Some respondents reported being challenged (often openly in class) by white male students and noted that having a higher ratio of non-male students in the class helped their evaluations. A considerable number of respondents also reported that their student feedback is highly dependent on the context of the class. Introductory classes, which contain more cisgender white male students, tend to procure lower ratings on student evaluations than subject-specific classes, which may be more diverse or in which student populations may self-select based on the specific topic of the class. A few respondents reported that they felt they could act as positive role models for female or nonbinary student populations.

The open-ended responses also suggest that students have different standards for male versus female-identifying instructors: they expect female-identifying instructors to be more nurturing and more accommodating, as well as easier graders than those identifying and appearing more male. As long as female instructors conformed to that gendered standard, students may even give them higher scores than their male peers. If they did not conform to gender-specific expectations, on the other hand, they felt they “got punished” for breaking gender-specific behavioral stereotypes on the evaluations. Nonbinary respondents and some who identified as “butch” women reported that they had the impression that students would sometimes allow them a more stereotypically “male” style of teaching without “holding them accountable” on the evaluations as they did with more traditionally “female-presenting” instructors:

As a butch woman, I feel as though I get evaluated as more caring than men do, yet I don’t get penalized like many feminine women do for seeming not as proficient. These sentiments have been reflected in my course evaluations.

Respondents also noted that they felt age played a role in how they were evaluated and treated by students. They reported that discriminatory and offensive comments on student evaluations subsided at least a little as they got older, compared with the beginning of their careers. Younger women in particular reported that they felt discriminated against, sometimes even harassed, by sexual comments about their bodies on student evaluations. They also reported a lack of respect for their credentials and expertise, especially in comparison with men their age or even younger.

Chappell and Waylen (Reference Chappell and Waylen2013) have explored the gendered nature of both formal and informal institutional norms of appropriateness. Within the confines of a gendered logic of appropriateness that is embedded in formal institutional rules, they note, consequences for violating those rules and norms would “have been met with official sanctions and punishment” (Chappell and Waylen Reference Chappell and Waylen2013, 606). However, institutional norms have changed over time, voluntarily or involuntarily, in part because activists pushed for the adjudication of those rules in official court, and in part because of what the authors call “broader cultural shifts” (607). This, in turn led to “a ‘crisis’ of the gender order” (607), causing a reform in formal institutional rules, but without eliminating male institutional bias, which continued to live on in many informal institutional norms. Expectations of what a professor “should look like” to elicit respect (i.e., cisgender male, older, white) and how male- and female-presenting professors should conduct themselves in the classroom may not only be part of the informal logic of appropriateness within academic institutions, but instead represent an informal logic of appropriateness within larger societal norms. These informal societal norms nevertheless appear to have a deep impact on students’ expectations regarding classroom behavior and interactions with their professors.

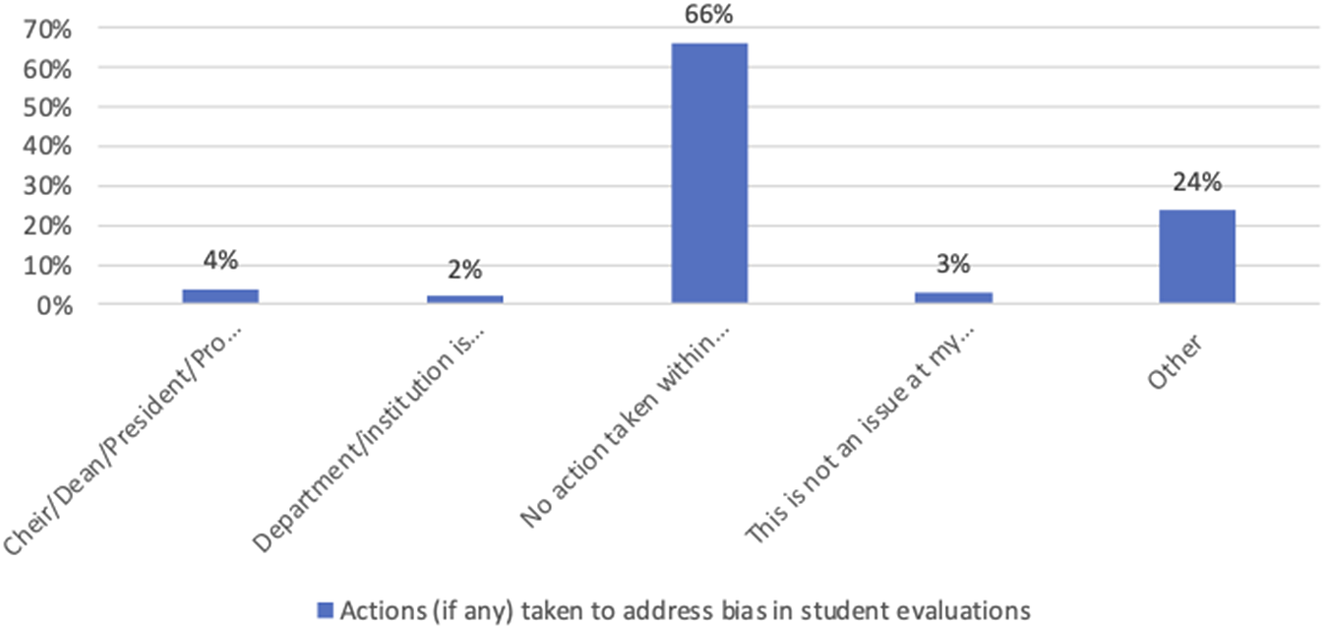

While bias against women and people of color in student evaluations is well documented in recent research, universities or departments appear to be anything from slow to uninterested in addressing the problem. As shown in Figure 8, a disconcerting 66% of respondents felt that no action had been taken on the issue at all. Almost 24% of respondents reported “other,” indicating that many may not be aware of any actions taken to address bias in student evaluations, or that institutions/departments continue to justify the use of student evaluations in hiring, tenure, and promotion decisions.

Figure 8. Institutional actions taken to address gender bias in student evaluations.

Based on the results of my survey, at the institutional level, the issue is met with inaction at worst, or unevenly addressed at best. It does appear that faculty and administrators at many universities “are aware” of the issue. In the open-ended responses, respondents reported that some universities had created committees to discuss next steps in addressing the issue. Others had decided to take evaluations “with a grain of salt,” de-emphasize them, or add other means of evaluation. Some chairs and administrators regularly send out emails to students during evaluation time, trying to raise awareness of the issue. Finally, some departments have completely stopped taking teaching evaluations into consideration in response to the recent studies on bias. Overall, however, it appears that coherent, university-wide action on the issue is still quite rare, which is surprising given the overall attention given to the issue in research and media coverage.

Thompson (2018), in examining resistance to institutional change, argues that a combination of critical actors resisting change, as well the explicit lack of a critical mass of women in any given institution has a compounding effect on resistance to change. In academic institutions, women are still not represented equally among administrative leadership. A 2020 survey by the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources cited in Inside Higher Education found that while female representation in academic administrative positions is growing, and more than half of university administrators are now women, women mostly occupy lower-level administrative positions and remain starkly underrepresented among administrative leadership (Whitford Reference Whitford2020). The lack of female representation in upper administrative positions critical to implementing change within American academia, as well as their lack of critical mass among department faculty, may help explain institutional hesitancy in addressing some of the fundamental issues inherent in student evaluations.

Institutional Responsiveness to Women

Respondents were also asked to evaluate the impact of their gender on their overall standing their departments. Overall, the perceptions of influence range broadly. Some senior faculty members and department chairs felt that they wielded enough influence and respect to really have an impact on the department’s culture. Others felt that gender- and race/ethnicity-related issues are too entrenched in their departments’ and institutions’ culture, so that it would be futile to even try to push for change. On the occasion that they did try, they were often reported to have been disappointed and gave up.

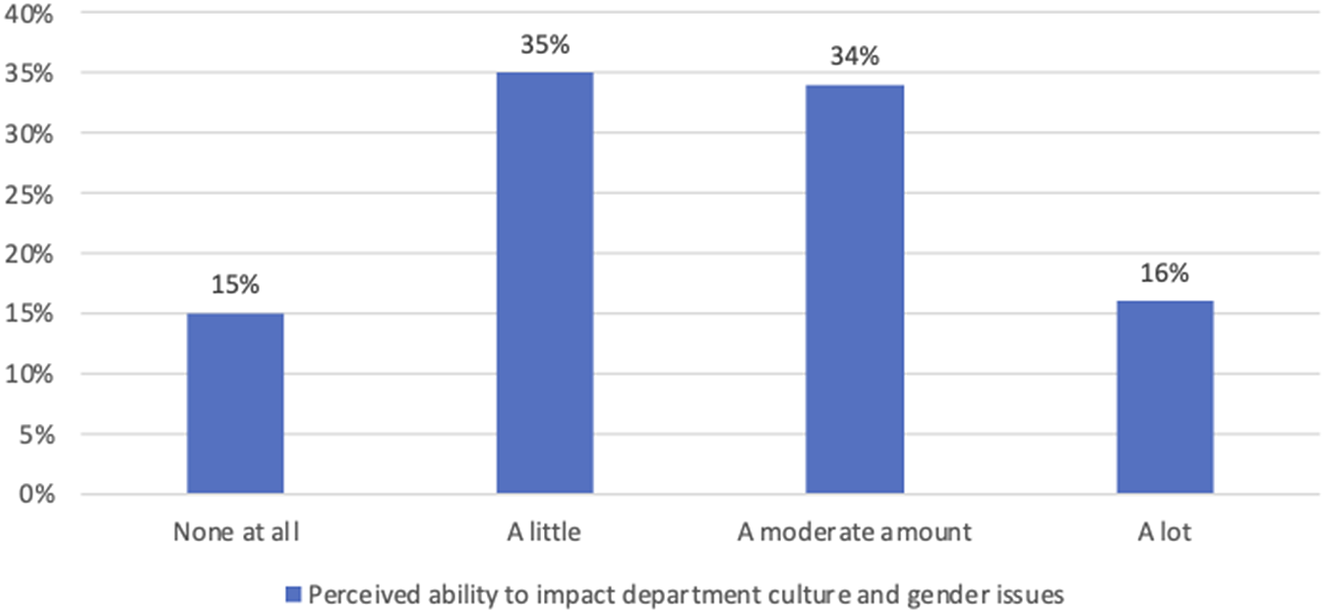

Regarding their ability to have an impact, respondents were equally divided: half said they had either no or very little impact on their department’s culture around gender issues, while the other half felt they had a moderate amount or a lot of impact (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Perceived level of ability to have an impact on department culture and gender issues.

In this case, too, comparisons between different groups of respondents reveal nuance based on the kind of institution and on faculty position. For instance, 48% of pre-tenure faculty women felt that they could have little or no impact on department culture, but only 39% of tenured faculty felt that way (p = .02). The protection of tenure, it follows, allows women to feel freer to try and make an impact on their departmental culture. A majority (54%) of women at PhD-granting institutions also felt that they could have little to no impact on their department’s culture, whereas only 33% of women at non-PhD-granting institutions felt that way (p < .001). This seems to indicate that a stronger institutional research focus further disadvantages and marginalizes women.

Some respondents, among them people of color and junior women with children, noted that female leadership is not always sensitive to the issues of all women, and that white female leadership in particular fails to create an inclusive culture for all colleagues, including those who are not white and cisgender.

The respondents’ perceptions of their ability to make an impact paint a nuanced picture that corresponds to different themes in the literature. The fact that perception of influence overall tends to increase with seniority (and, presumably, increase in professional power) appears to square with the notion that critical actors (i.e., people, regardless of their gender, in key positions) are crucial to either bringing about positive gendered change (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009) or to resisting such change (Thompson Reference Thomson2018). My respondents’ reservations about white female leadership underscore the importance of not just gender but also race and ethnicity in representation, but they also underscore the fact that no actor can be presumed to work toward positive institutional change solely based on their (gender, racial, or ethnic) identity. Numerical representation and critical mass of women and historically marginalized groups represents one step toward institutional change, but critical actors invested in the cause are another key ingredient.

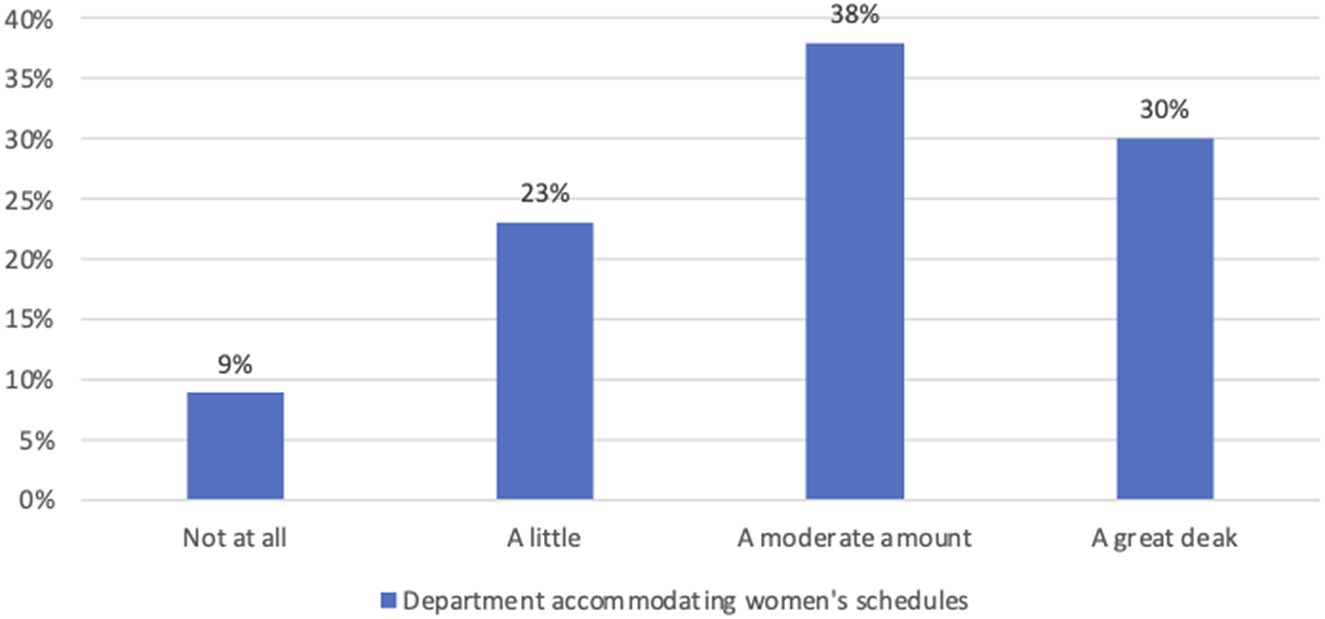

The survey also included a question on department responsiveness regarding “women’s schedules.” That question was purposefully kept vague, as to get a better understanding of respondents’ spontaneous definitions of “women’s schedules.” Overall, as shown in Figure 10, a clear majority thought that their department was mostly accommodating regarding women’s schedules.

Figure 10. Departments’ willingness to accommodate women’s schedules.

Though only 32% found their departments to be less or not accommodating at all, the comparisons across groups, as shown provide important additional details. When comparing faculty (at all levels) and PhD students, perceptions of departmental levels of accommodation for women’s schedules differ drastically. Almost twice as many PhD students (46%) thought that their department was little or not at all accommodating to women’s schedules, whereas only 23% of all faculty thought so (p < .001). As with other gender-related issues, PhD-granting institutions seem to be less accommodating than non-PhD-granting institutions. Only 19% of women at non-PhD-granting institutions felt that their department was little or not at all accommodating, whereas 29% of women at PhD-granting institutions felt that way (p = .003).

The open-ended responses shed even more light: most were in reaction to course scheduling and family accommodations provided by their university. This assumes that women tend to see themselves as the primary caregivers to children, which is reflected in the research (Glynn Reference Glynn2018; OECD 2014). Of course, gender-specific needs extend beyond caregiving for children, as women also tend to be main caregivers for family members who are elderly or have a disability (Boesch Reference Boesch2020). These differences became even more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many women lost what few structures they had in place to support their care work.

Several studies (Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz Reference Bertrand, Goldin and Katz2010; Goldin Reference Goldin2014) have found that the biggest equality lag in the profession is related to childbearing. Motherhood, for women, seems to be associated with the biggest growth in the gender wage gap in their careers (Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz Reference Bertrand, Goldin and Katz2010; Goldin Reference Goldin2014). Men, on the other hand, do not experience any salary lags associated with fatherhood, suggesting that becoming a parent perpetuates the gender wage gap and severely hampers professional upward mobility for women.

This, once again, speaks to the fact that institutional norms of appropriateness, where the expectations of how parenthood will affect men and women’s respective work performance, are deeply gendered. While parenthood itself is not a violation of the institutional norms of appropriateness, an interrupted work record, because of the lack of domestic support, might be seen as such (see, again, Chappell Reference Chappell2006, 228). Men who become parents tend to benefit from the assumption that they have a stay-at-home partner who will take on the onus of childcare, while women do not. Galea et al. (Reference Galea, Powell, Loosemore and Chappell2020, 1226) note that “paid maternity leave may now be called parental leave but it continues to be modelled around informal rules that maintain traditional gender roles that reinforce women’s role as carer and men’s role as breadwinner.” So, while formally, many institutions appear “family-friendly” and “inclusive,” “informal institutions in many organizations tend to relegate women to the homemaker role, enforce normative heterosexuality, and/or privilege men in the family and leadership positions” (Galea et al. Reference Galea, Powell, Loosemore and Chappell2020, 1226). Focusing on women in the construction industry, Galea and coauthors found that informal institutional rules around parental leave ultimately had a damaging effect on the retention and career progression of women in the industry, in part because they were reinforcing (as mentioned above) deeply gendered notions about caregiving.

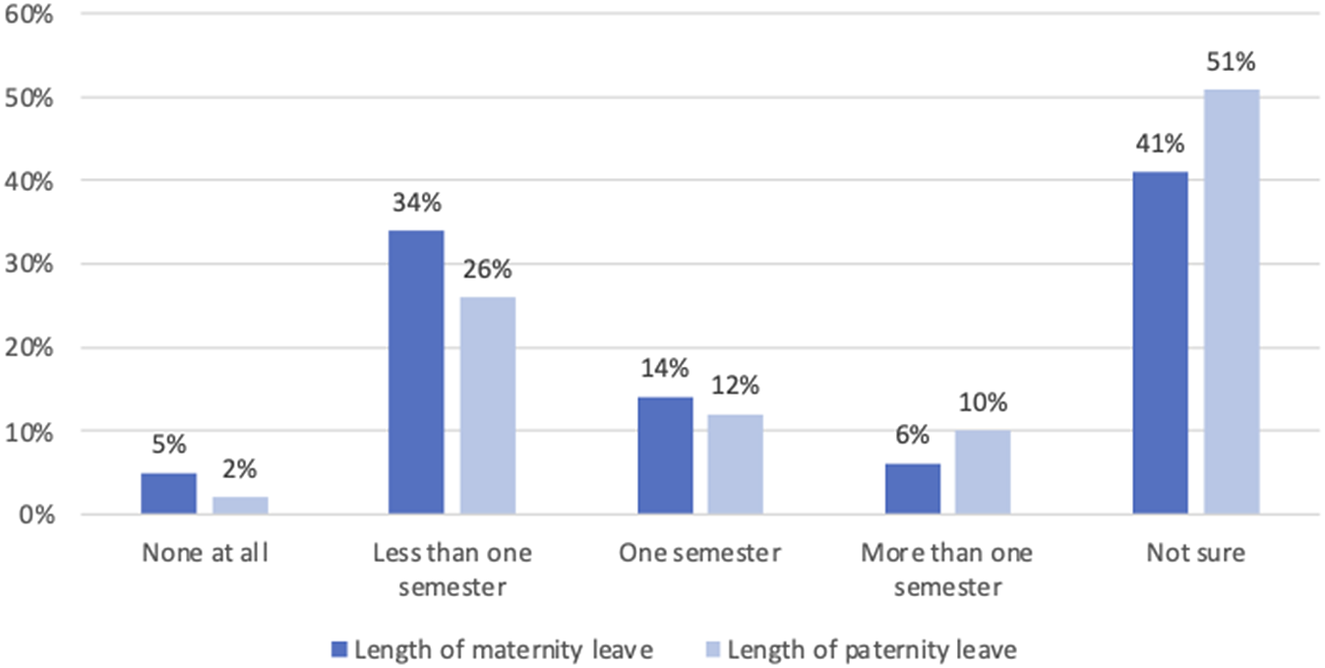

Women in political science departments seem to encounter quite fundamental issues around parenthood: Parental leave is still not universally available at American universities, and in the American workplace in general. Figure 11 shows the responses of faculty (tenured or tenure-track) regarding maternity and paternity (sometimes “parental”) leave policies at their institution.

Figure 11. Length of maternity/paternity leave (paid/unpaid).

Two things stand out. First, the availability and length of parental leave for female- and male-identifying faculty does not seem to differ much, suggesting that most universities that have implemented leave policies for parents make that leave available regardless of gender identification. This implies a growing separation in formal institutional norms of accommodations for having children from female identity, specifically. Second, a large percentage of respondents (almost half) were not sure about leave policies at all, so these results should be taken with a grain of salt. The reason for this could either be that a majority of respondents (60%) do not have any children and therefore never had to deal with institutional parental leave policies, or poor or informal information about parental leave policies on the part of the university, or a combination of both.

In addition, a comparison across groups shows significant institutional difference in the availability of parental leave for women: 72% of all respondents at non-R1 institutions reported that at least some leave was available to them, whereas only 42% of respondents at R1 institutions said so (p < .001).

Graduate students and pre-tenure faculty members tend to feel the pressures of judgment more harshly than those who enjoy the protection of tenure. Among graduate student respondents, 51% were not sure what their institution’s maternity leave policy was, and an even larger number, 61%, did not know about their institution’s paternity leave policy. This creates a large amount of uncertainty for graduate students and, based on the qualitative responses, suggests that decisions about leave policies are made on a case-by-case basis for graduate students, making them vulnerable to unsympathetic advisors and department leadership. “It [the provision of accommodations] depends on who is chair,” was a common response to the open-ended question. This is problematic, as it creates an unfair environment for women in departments, depending on who is in charge of the scheduling. It may also lead graduate students to seek out more accommodating professors to work with, many of whom, in turn are women:

“It’s up to each individual professor how they want to respond to these sorts of requests [for parental leave or childcare accommodations], and as a female in a student position, not much can be done but to hope you don’t get in a situation with one of these professors. Then of course, this ultimately falls on female professors, and then they are disadvantaged with less research assistance.”

A number of professors echoed this concern by graduate students, arguing that women, especially women of color, and nonbinary people are more often sought out as mentors and advisors than cisgender white men. They feel they are sought out because they are more accommodating, understanding, and sensitive to the needs of historically underrepresented populations. While their perspectives are crucial in supporting their advisees, their popularity also adds considerably to their advising and service load. Prior research underscores this finding, showing that women tend to take on a much higher burden of service work (Kantola Reference Kantola2008; O’Meara et al. Reference O’Meara, Kuvaeva, Nyunt, Waugaman and Jackson2017).

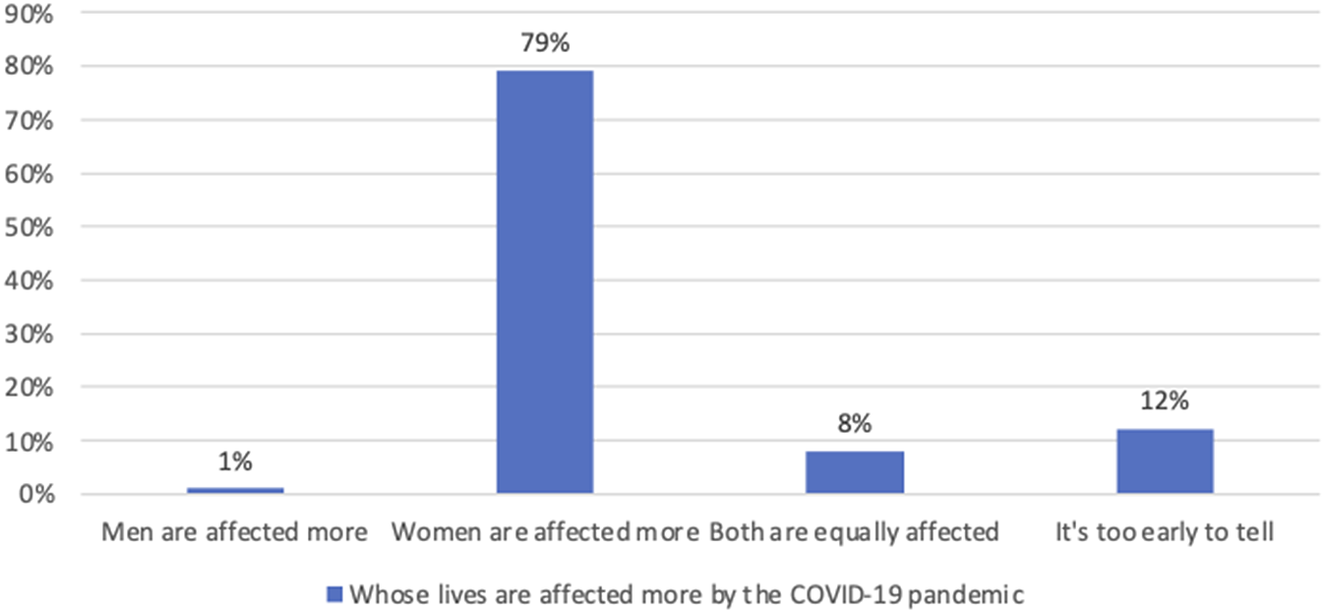

The COVID-19 pandemic added another layer of complications for working parents and caregivers, and especially so for women (Boesch Reference Boesch2020). This survey was conducted at the very beginning of the pandemic, in the early summer of 2020. At that point, respondents could only speculate about the effects this would have on their personal and professional lives. However, even early on, their outlook was not positive: almost 80% of respondents thought that women would be affected more by the pandemic.

Comparing groups, women’s career level seemed to be highly relevant to their perceptions of the effects of the pandemic on them, compared with men: 88% of pre-tenure women felt that women’s careers would be more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, compared with 76% of tenured women (p = .005) (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Perceived effect of COVID-19 on the lives women and men.

As teaching and meetings transitioned to an online format, most childcare accommodations fell apart, leaving parents (and particularly mothers) to simultaneously fill roles as teachers, caregivers, and full-time employees. Workplace accommodations were minimal. Caregiving responsibilities disproportionately fell to women (Bahn, Cohen, and Rodgers Reference Bahn, Cohen and van der Meulen Rodgers2020; Minello Reference Minello2020; Shalaby, Allam, and Buttorff Reference Shalaby, Allam and Buttorff2021), with major implications for their future career trajectories and earnings projections.

Discussion and Conclusions

This research offers some key insights into the predicaments of women in academia: academic institutions in general, and political science departments in particular, are still driven by highly gendered institutional norms. The institutional logic of appropriateness governing political science departments appears to highly gendered in the sense that it is based on male norms of behavior, of work and research themes, work habits, and performance evaluation. This gendered logic, which governs not only day-to-day life but also academics’ chances to achieve tenure, promotion, and merit-based salary increases, has serious implications for women’s careers, earnings, and general social upward mobility. Perhaps one of the most shocking findings of this research is that so little has been done to remedy in some (any) way the gender bias in student evaluations, which has been illustrated in peer-reviewed political science research (see Chavez and Mitchell Reference Chavez and Kristina2019). Among the respondents surveyed for this research, 66% reported that there had been absolutely no action taken at the university or departmental level to address this bias—in spite of scientific evidence!

Previous research by feminist institutionalist scholars has established that institutions change notoriously slowly (see Mackay Reference Mackay2014; Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010; Meyerson and Tompkins Reference Meyerson and Tompkins2007; Thomson Reference Thomson2018), as their very organizational structures and processes are predicated on gendered norms of appropriateness (Chappell Reference Chappell2006) or “‘male’ measurements of success,” to borrow a term from Shalaby, Allam, and Buttorff (Reference Shalaby, Allam and Buttorff2021). This is in spite of the fact that many institutions have started to focus on hiring more personnel from traditionally marginalized groups, as well as more women. However, even as the composition of many departments may be incrementally changing, gendered norms may remain in place (or may even be reinforced) in informal institutional behavior, such as networking (Kenney Reference Kenney1996; Leach and Lowndes Reference Leach and Lowndes2007; Mackay Reference Mackay2014). Sexual harassment and violence are also frequently used against women to reenforce or “restore” traditional gendered institutional norms (Collier and Raney Reference Collier and Raney2018). The results of this survey indicate that sexual harassment is not a rare occurrence, especially among junior female faculty and PhD students.

Parenthood is another factor that vastly exacerbates the gender pay gap. In anticipation of this, many women in academia choose not to be mothers (as this survey shows, the anticipated impact of motherhood on one’s career is bleaker than the perceived impact by respondents who are mothers). Furthermore, female advocacy may not be as intersectional as many women in the profession would hope, as women of color and women who are mothers tend to feel excluded from the agendas of (white) women in academia.

What sorts of institutional configurations may then reasonably bring about positive institutional change for women? Key scholars of feminist institutionalism have suggested that either a critical mass of women employed within institutions can force formal and informal institutional norms to change, over time, to become more inclusive and accommodating to women’s needs, perspectives, work schedules, preferences, and contributions (Kenney Reference Kenney1996; Leach and Lowndes Reference Leach and Lowndes2007; Mackay Reference Mackay2014). Others have argued that merely focusing on critical mass leads us to make too many (perhaps unfounded) assumptions about the behavior and priorities of female actors, simply based on their gender (Childs and Krook Reference Childs and Krook2009; Thomson Reference Thomson2018). They note that critical actors—institutional actors in powerful positions, invested in creating positive gendered institutional change, regardless of their gender—are the key ingredient to achieve meaningful changes in gendered institutional norms.

Many findings from my survey underscore the argument made by Childs and Krook (Reference Childs and Krook2009) that a critical mass of women alone is not enough to bring about positive gendered change within institutions. Female advocacy networks are not enough to protect women from discrimination, harassment, and career disadvantages, and they cannot eliminate the gender pay gap. Instead, institutions must fundamentally change their gendered norms of appropriateness and implement new policies to accommodate women and the specific challenges they face, as women, people of color, and mothers, and to use fairer measures to evaluate women’s research, in both methodology, outlook, and funding. This can only happen if individuals critically positioned to bring about such changes show a vested interest in such change and are willing to provide the institutional “push” to bring it about.

However, at the same time my research suggests that increased representation among departmental faculty can and often does create a more comfortable work environment and provide PhD students and junior faculty with mentors and role models. Intersectionality seems crucial (but is often missing) in this context: while women remain an underrepresented group among political science faculty, women of color make up by far the most underrepresented group, and, according to the open-ended responses, they feel a lack of support and understanding from their (mostly white) peers. Institutional change cannot be realized without understanding the perspectives of the excluded and historically marginalized. We can only see the gendered nature of institutional norms if we take into consideration the female perspective (which differs, in many ways) from the male standard. Similarly, we must understand that institutional norms that cater exclusively to the needs and perspectives of white women cannot be understood to be the “female standard.” The survey results presented here indicate that positive intuitional change hinges on both, critical actors in positions of power that allow them to implement institutional reforms, and a critical mass of women and historically marginalized groups that can help to provide the different institutional perspectives that underpin such reforms.

The findings presented here underscore the urgent need for new perspectives in how the workplace is structured, but they also point (as many feminist institutionalists have done) to a conundrum: without profound gendered (and intersectional) change, women will have a more difficult time to rise to critical positions in the workplace where they can make a key difference. And without these critical actors, change will be more difficult to bring about.

The survey results also underscore the need for broader policy reform. As the COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare, caregiving (especially for children) still falls predominantly to women. Professional childcare is patchy at best, and too expensive for many, leaving most women profoundly disadvantaged in the workplace. The state can help alleviate this burden by providing readily available, reliable, and affordable childcare for all families who want it.

Further research is needed on intersectionality and the specific challenges faced by women of color, who remain woefully underrepresented and under-researched in the profession. Furthermore, research on the growing pool of “contingent faculty,” who face different and more severe challenges than tenured and tenure-track faculty would add important additional nuances.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X23000399.

Acknowledgments