Abstract

Debreu (American Economic Review 50:186–188, 1960) famously criticized Luce (Individual choice behavior, Wiley, New York, 1959) choice model with what became known as the red-bus blue-bus example: if a choice set contains two distinct alternatives C (car) and B (blue bus) then adding a third alternative A (red bus) that is essentially identical to B does not affect the choice probability of C but reduces the choice probability of B by half. Debreu’s critique highlights the existence of substitution effects violating the principle of independence from irrelevant alternatives—the cornerstone of Luce (Individual choice behavior, Wiley, New York, 1959) choice model. This paper weakens this principle to construct a model of probabilistic choice satisfying Debreu’s critique.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Debreu (1960, p. 188) originally used the example of the Debussy quartet, the 8th symphony of Beethoven and the same symphony with a different conductor.

Reversely, if a is more desirable than c and b is exactly in-between, the decision maker chooses b over c with the same probability as he or she chooses a over b. Fortunately, under probabilistic completeness, P(a,b) = P(b,c) is equivalent to P(b,a) = P(c,b).

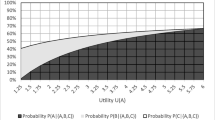

In contrast, in Luce (1959) choice model, all choice probabilities are monotone in u(b) and they are not at all related to ternary choice probabilities.

References

Ben-Akiva, M. (1973). Structure of Passenger Travel Demand Models, PhD dissertation, Department of Civil Engineering, MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Davidson, D., & Marschak, J. (1959). Experimental tests of a stochastic decision theory. In C. W. Churchman & P. Ratoosh (Eds.), Measurement: definitions and theories (pp. 233–269). Wiley and Sons.

Debreu, G. (1960). Individual choice behavior: A theoretical analysis. By R. Duncan Luce. American Economic Review, 50, 186–188.

Debreu, G. (1958). Stochastic choice and cardinal utility. Econometrica, 26(3), 440–444.

Estes, W. K. (1960). A random-walk model for choice behavior. In K. J. Arrow, S. Karlin, & P. Suppes (Eds.), Mathematical methods in the social sciences (pp. 265–327). Stanford University Press.

Faro, J.H. (2023). The Luce model with replicas. Journal of Economic Theory, forthcoming.

Gul, F., Natenzon, P., & Pesendorfer, W. (2014). Random choice as behavioral optimization. Econometrica, 82, 1873–1912.

Kovach, M., & Tserenjigmid, G. (2022a). The Focal Luce Model. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 14(3), 378.

Kovach, M., & Tserenjigmid, G. (2022b). Behavioral foundations of nested stochastic choice and nested logit. Journal of Political Economy, 130, 2411–2461.

Li, J., Tang, R. (2016). Associationistic Luce Rule. Research Collection School Of Economics, available at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soe_research/2305

Luce, R. D. (1959). Individual choice behavior. Wiley.

Luce, R.D., Suppes, P. (1965). Preference, utility, and subjective probability. in Handbook of Mathematical Psychology, vol. III, pp. 249–410, John Wiley and sons.

McFadden, D. (1978). Modeling the choice of residential location. In A. Karlqvist, L. Lundqvist, F. Snickars, & J. Weibull (Eds.), Spatial interaction theory and planning models (pp. 75–96). North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Tversky, A. (1972). Elimination by aspects: A theory of choice. Psychological Review, 79, 281–299.

Williams, H. (1977). On the formation of travel demand models and economic evaluation measures of user benefits. Environment and Planning A, 9, 285–344.

Acknowledgements

Pavlo Blavatskyy is a member of the Entrepreneurship and Innovation Chair, which is part of LabEx Entrepreneurship (University of Montpellier, France) and is funded by the French government (Labex Entreprendre, ANR-10-Labex-11-01). I would like to thank the editor Matthew Ryan and one anonymous referee for their very helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Proof of proposition 1

Multiplying conditions (5), (6), and (7) yields us Eq. (18) which is known as the product rule (e.g., Estes, 1960, p. 272; Luce & Suppes, 1965, definition 25, p. 341).

According to Theorem 48 in Luce and Suppes (1965, p. 350), binary choice probabilities satisfy the product rule (18) if and only if there exist a positive real-valued utility function \(u\), unique up to multiplication by a positive constant, such that for any two choice alternatives a, b binary choice probability is given by (8).

Solving the system of Eqs. (1), (5), (6), and (7) yields us ternary choice probabilities (9)-(11), which are different from Luce (1959) choice model.

Q.E.D.

1.2 Proof of proposition 2

Proof by mathematical induction.

-

Step 1. For n = 3 conditions (13)–(15) become (5)–(7) correspondingly and proposition 1 implies that there exist a real-valued utility function \(u\), unique up to multiplication by a positive constant, such that binary choice probabilities take form (8) of binary Luce (1959) choice model. Ternary choice probabilities are then given by (9)–(11) and Proposition 2 is satisfied.

-

Step 2. We assume that Proposition 2 holds for any n ≤ m-1.

-

Step 3. We shall prove that Proposition 2 also holds for n = m.

If binary choice probabilities take form (8) of binary Luce (1959) choice model and probabilities \(P\left({a}_{i}|S\backslash \left\{{a}_{i+1}\right\}\right)\) and \(P\left({a}_{i+2}|S\backslash \left\{{a}_{i+1}\right\}\right)\) are given by (16) by step 2 then condition (13) can be rewritten as (19) for i ∊ {1, …, m-2}.

Analogously, condition (14) becomes (18) and (15)–(19).

Solving the system of Eqs. (17)–(19) then yields

and

for i \(\in\) {2, …, m-2}.

By mathematical induction Proposition 2 then holds for any finite n.

Q.E.D.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Blavatskyy, P.R. Debreu’s choice model. Theory Decis 96, 297–310 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-023-09947-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11238-023-09947-7