Abstract

The current study aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of threat and efficacy appraisal and account for the influence of disparity in the accessibility to risk prevention resources in predicting attitudes and behaviors. We propose a Risk-Efficacy Framework by integrating theories, including the extended parallel process model, health belief model, social cognitive theory, and construal level theory of psychological distance to achieve such a goal. An online survey targeting the U.S. population was conducted to empirically test the model (N = 729). The survey measured people’s threat and efficacy appraisals related to COVID-19 and its vaccines and their attitudes and behavioral intention. The results of the survey supported the model’s propositions. Specifically, perceived susceptibility moderated perceived severity’s effects on attitudes and behaviors, such that perceived severity’s influence attenuated as perceived susceptibility increased. Perceived accessibility to risk prevention resources moderated the influence of self and response efficacy. The former’s effects on attitudes and behaviors increased, and the latter’s effects decreased when perceived accessibility was high. The proposed framework provides a new perspective to examine the psychological determinants of prevention adoption and contributes to designing and implementing campaigns distributing prevention to underserved populations. The framework offers insights for risk managers such as public health authorities by articulating the dynamic nature of risks. When communicating early-stage lesser-known risks to the public, campaigns should highlight their severity and the response efficacy of risk solutions. Differently, more resources should be devoted to cultivating self-efficacy for widespread risks with more mitigation resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persuading people to adopt behaviors that prevent negative consequences has long been a central theme of psychology research. Correspondingly, theories have been proposed to illustrate factors that contribute to the initiation of risk prevention behaviors, such as Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) (Rogers, 1975), Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM) (Witte, 1992), and Health Belief Model (HBM) (Janz & Becker, 1984). Though these theories differ in scopes and constructs, two sets of variables related to people’s assessment of the risks and ways to overcome such risks are often considered key determinants of risk prevention behavior and the success of messages promoting such behaviors. The first set of variables, termed threat appraisal in the EPPM and PMT, or risk perception in other models, focuses on the evaluation of the magnitude and probability of a risk’s adverse effects (Rogers, 1975; Witte, 1992). The other set of variables, often labeled efficacy appraisal, describes a person’s perception of the means that prevent such adverse effects (Witte, 1992). Despite differences in terminology, threat and efficacy appraisals are considered key predictors of attitudes, behavioral intention, and behaviors associated with risk prevention, ranging from getting vaccinated, screening for cancers, and climate change mitigation (Chu & Liu, 2021a; Witte & Allen, 2000; Xue et al., 2016).

Threat and efficacy appraisals are often operationalized with two pairs of sub-dimensions. Perceived susceptibility, which denotes a person’s perceived probability of a threat occurring, and perceived severity, which characterizes the perceived magnitude of such a threat, are often utilized to operationalize threat appraisal (Rogers, 1975; Witte, 1992). For example, a threat that is highly likely to occur and causes severe negative consequences, such as the earlier variants of COVID-19, tends to be perceived as a greater threat than a less severe and unlikely risk, such as water intoxication (i.e., disrupted electrolyte balance due to drinking too much water). Efficacy appraisal is also commonly measured with two constructs: self and response efficacy. Self-efficacy, also a core concept in the Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 2001), is related to a person’s belief regarding their ability to perform a behavior that may prevent obnoxious events (i.e., threats) from taking place. Response efficacy instead focuses on the individual’s evaluation of a prevention’s effectiveness in averting the threat (Popova, 2012). For example, a person believing that using a condom is easy and effective in preventing AIDS may be more likely to use it than one who does not believe so (Witte, 1992). Notably, threat and efficacy appraisals are perceptual variables that may be influenced by individual experience and exposure to messages illustrating a threat and recommending threat-prevention behaviors (Popova, 2012). They should not be interpreted as features of a message, despite the latter’s influence on it. In the current study, we focus on people’s perception of threat and prevention and seek to provide insights into risk communication message design.

As illustrated earlier, different models use different terms to describe threat and efficacy appraisal. They also configure these variables differently. In the HBM, perceived severity, susceptibility, and self-efficacy are often modeled independently as predictors of the outcome variables (Janz & Becker, 1984) (Note, response efficacy is not included in the original HBM). In the EPPM, threat and efficacy appraisal subdimensions are often averaged into respective predictors of people’s attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors (Witte, 1992; Witte & Allen, 2000). Though the additive models were widely utilized in recent decades (Gore & Bracken, 2005; Yang & Chu, 2018), they were not the original formulation of the constructs, particularly threat appraisal. Rogers (1975) and Witte (1994), in their seminal pieces on the PMT and EPPM, suggested a multiplicative configuration of threat appraisal; that is, the construct should be operationalized as the product term of perceived susceptibility and severity. Of note, the multiplicative setup was inspired by the expectancy-value theory (Atkinson, 1964). Severe risks of very low probability, such as volcanic eruption in a low-volcanic-activity area, may not be perceived as a significant threat, and so are high-probability-low-severity risks (e.g., catching a cold). Despite the theoretical value of the multiplicative model, more recent studies utilized the additive model with a few exceptions (Lu et al., 2020; Rimal & Real, 2003). However, as illustrated above, the additive model does not account for cases where perceived susceptibility and severity are incongruent (e.g., low susceptibility and high severity risks), calling for refinement of the configuration of threat appraisal.

Unlike threat appraisal, there is not as much debate on the configuration of efficacy appraisal (Popova, 2012). Theory-testing and applied studies often model perceived self and response efficacy independently or additively as the predictors of prevention behaviors (Tannenbaum et al., 2015; Witte & Allen, 2000). However, despite accounting for individuals’ perceived ability to adopt a prevention tool or strategy and the prevention’s capability to thwart the development of threats, most extant models fail to consider the disparity in people’s access to prevention resources. Due to socioeconomic inequity, underserved individuals and communities often do not have equitable access to the resources necessary to address health and environmental threats, and such inequity tends to exert more negative impacts on those more susceptible to such threats (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015; Braveman, 2006; Braveman et al., 2011). For example, though people may know how to process and cook healthy food and understand its effectiveness in promoting health, the lack of access to such food choices may limit efficacy perceptions’ effects on actual behavior (Lattimore & Halford, 2003). Of note, self-efficacy, which captures a person’s belief about their ability to both access and utilize the prevention (Witte, 1992), is related to the disparity. However, subsuming both accessibility and feasibility under one construct causes conceptual ambiguity and obscures our understanding of the influence of structural disparity in influencing people’s response to risks. In the meantime, operationalization of self-efficacy also tends to focus more on the ability to use (e.g., knowing how to use family planning properly) instead of access (e.g., being able to afford family planning). Perceived accessibility of a prevention tool or strategy is thus a necessary component of models predicting people’s response to different risks.

Despite the wide application of threat and efficacy appraisals in psychology and communication theories, we need to improve our understanding of their impacts on people’s attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behaviors associated with risk prevention. Particularly, an updated model needs to refine the configuration of the subdimensions of these two types of appraisals and the role of disparity in people’s access to prevention resources. Based on the existing models, such as the EPPM and PMT, we incorporate the construal level theory of psychological distance to propose a Risk-Efficacy Framework that repackages the threat and efficacy appraisal’s influence on risk prevention attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, this model accounts for the effects of resource disparity by assessing the moderating role of perceived accessibility to prevention tools and strategies. In the following section, we illustrate the new model by first delineating the role of construal level and psychological distance. We then present the detailed configuration of the new model.

Construal level theory of psychological distance

The construal level theory of psychological distance (CLT) is one of the most influential theoretical advancements in psychology in the past decades. The theory argues that a person’s response to objects, events, and people is influenced by the psychological distance between the perceiver and the perceived stimuli (Trope & Liberman, 2010). CLT further posits that psychological distance shapes a person’s mental representation of the perceptual target (i.e., mental construal). Specifically, as the perceived distance of an object increases, the abstractness of its construal also increases. At the same time, the concrete details fade away in people’s mental representation of the target object. Consequently, their evaluation, judgment, and response to a distal stimulus are likely shaped by its abstract characteristics, such as the general shape and value (Trope & Liberman, 2010). As noted above, CLT has been widely utilized in psychology and communication research. For example, environmental psychology researchers employed CLT to examine people’s response to physically distant environmental hazards caused by climate change (Chu & Yang, 2020; Spence et al., 2012), and health psychology research utilizes the theory to explain the impacts of health threats that are temporally distant to individuals (Xu et al., 2020). Interpersonal communication researchers also utilize CLT to explain people’s interaction with socially distant or close individuals (Stephan et al., 2010), and human–computer interaction research also recognizes the theory’s value (Mumm & Mutlu, 2011).

One notable trend in the application of CLT in social psychology and communication research is the focus on its applied value, that is, using constructs from the theory to explain or predict observed phenomena. In other words, most applied CLT studies build hypotheses and research questions with constructs from the theory (e.g., perceived distance of a health or environmental threat) instead of extending the theory to explain the relationship among existing variables. In contrast, some classic theories have been more organically integrated into social psychology and communication theories and models. For example, the risk information seeking and process model (RISP) builds on the heuristic-systematic model (Chaiken, 1980) and theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) to predict people’s intention to seek and systematically process risk information (Griffin et al., 1999). The extended parallel process model (EPPM) and the earlier protection motivation theory (PMT) were also built upon the classic value-expectancy theory to explain people’s response to fear appeal messages (Rogers, 1975; Witte, 1992). Seeing as CLT has been widely applied in social psychology research, it is meaningful to further explore its utility in explaining and predicting the relationship among important variables.

The first step in such an endeavor is to take a closer look at the core propositions made by CLT. As the name implies, CLT focuses on two constructs: psychological distance and construal level. Psychological distance, as illustrated earlier, pertains to the relationship between a perceiver and the object they are perceiving. The theory articulates that such perception has four interrelated dimensions, including spatial, social, temporal, and hypothetical dimensions (Trope & Liberman, 2010). The first three dimensions are more intuitive to people’s perception of the physical world. A person is more likely to perceive something distant in the physical space (e.g., 100 km away compared to 10 m away), social network (e.g., a total stranger compared to a spouse), and time spectrum (e.g., 100 years in the future compared to tomorrow) as psychologically distant. Hypothetical distance, on the other hand, denotes the perceived probability of an event occurring, such that uncertain events are perceived as more distant than certain ones (Trope & Liberman, 2010). CLT postulates that variations in these dimensions are interrelated such that perceived distance on one dimension tends to spill over into people’s perceptions of other dimensions (Bar-Anan et al., 2007).

Another important construct in CLT is the construal level. As noted earlier, people’s mental construal of a distant object is often more abstract and with fewer concrete details. Trope and Liberman (2010) attribute such a tendency to the loss of contextual details in the processing of distant stimuli. Indeed, as the capacity of our working and long-term memory is limited (Lang, 2000), it may be difficult to construct a concrete and vivid mental representation of something that happens in a faraway place, to a stranger, in a distant future or past, and of low certainty, without the aids of external resources. The consequence of the distance-contingent variation in construal level is thus the “construal-mediated effects of psychological distance” (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Specifically, stimuli feature central to the perceptual target (i.e., abstract and high-level) may exert a stronger influence on people’s response to it at a far distance, but concrete, low-level features may weigh more in encounters with psychologically close objects. Such a proposition has received wide empirical support. Abstract features, such as the desirability, the general category, shape, and the core value of a distant object, were found to exert a stronger influence on people’s judgment, evaluation, and actions (Adler & Sarstedt, 2021; Trope & Liberman, 2010). Differently, concrete features, such as the feasibility of behavior and the idiosyncratic characteristics of a person or object, were more influential in people’s response to nearby objects (Goodman & Malkoc, 2012; Todorov et al., 2007; Trope et al., 2007).

After illustrating the basic premises of CLT, an important question to address is how to utilize them to explain the complex interplay of risk constructs key to our research. We propose a Risk-Efficacy Framework that reconfigures threat appraisal, efficacy appraisal, and perceived accessibility to predict people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses to threats.

Threat appraisal

As illustrated earlier, threat appraisal is often operationalized with two subdimensions, including perceived susceptibility and severity of a threat. The former denotes the perceived probability of the threat causing damage to the perceiver, and the latter represents the perceived magnitude of such damage (Popova, 2012). It is not hard to notice the similarities between perceived susceptibility and hypothetical distance. From the conceptual perspective, both constructs anchor on the perception of the probability of an event (or threat) happening, while from the applied perspective, lower susceptibility perception often indicates that the threat is not an imminent danger to the perceiver themselves or the people they care about (i.e., far distance). Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that perceived susceptibility may function similarly to psychological distance, such that it may condition the influence of high- or low-construal-level factors in shaping people’s response to a threat.

What might be the high or low-level factors in people’s decision-making related to risks? We argue that perceived severity may be one of the higher-level factors. The CLT offers two criteria for determining a factor’s construal level: centrality and subordination (Trope & Liberman, 2010). Centrality is related to a factor’s role in determining the intrinsic meaning of an object. The more central a factor is to the object, the higher its construal level is. For example, transporting people is a central feature of vehicles, while having four wheels is peripheral. Therefore, an abstract mental construal of a vehicle may be more likely to retain the information about its use as a transportation tool but not how many wheels it has. The subordination principle is a derivative of the centrality principle. It indicates that changes in the low-level factors are less likely to alter the meaning of an object than the changes in the high-level factors. For example, a vehicle that does not have four wheels may still be a vehicle (e.g., a bike), but a vehicle that does not transport people or goods is not considered a vehicle.

In the context of threat appraisal, perceived severity may be considered a high-level factor due to its centrality to people’s evaluation of the threat and other factors’ subordination to it. Specifically, a threat that does not lead to severe damage is not considered a threat, regardless of other characteristics. For example, though a plane crash is very unlikely to most people, many still consider it a threat due to its severe consequences. Differently mosquito bites are common in many places, but many still do not recognize them as a serious threat to their health (except for those in regions suffering from mosquito-borne disease, which also increases the severity of mosquito bites). Classic risk perception research provides some support for such a claim. For example, though experts often rate low-probability-high-severity threats such as nuclear power as less salient, laypeople often exaggerate its significance (Slovic et al., 1981). Additionally, other factors, such as the availability and effectiveness of prevention, are also subordinate to the central role of severity perception (Chu & Liu, 2021b). In essence, people consider a threat threatening because it is severe.

Based on the theorization above, it is arguable that perceived susceptibility and severity may interact to influence people’s response to a threat. Particularly, severity perception as a high-level factor may weigh more in people’s consideration of a less susceptible threat (i.e., far distance), while its effects may attenuate as the perceived susceptibility increases (Proposition 1). The implication of such a proposition is twofold. First, when perceived susceptibility is low, a more severe threat is more likely to instigate attitudinal and behavioral responses in people than a less severe threat. For example, when the earlier cases of the COVID-19 pandemic were reported in China, people in the U.S. and other distant countries may be more likely to take preventive actions such as buying disinfectants when they perceived it as a severe threat (Yang et al., 2022). The second implication of such a proposition is that severity perception may be less likely to determine people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses among highly susceptible individuals. Instead, this group may rely more on the concrete consideration of the risks, such as how feasible the risk prevention tools are to determine their subsequent actions (Chu & Liu, 2021b; Chu & Yang, 2020). Though they are based on different theoretical premises, EPPM also makes similar propositions. Specifically, it argues that high severity and susceptibility perception may trigger defensive reactions to messages about certain threats, especially when there is an insufficient level of efficacy perception (Witte, 1992).

It is notable that such a proposition is not equivalent to the multiplicative model of threat appraisal illustrated earlier. The multiplicative model operationalizes threat appraisal or risk perception as the product term of perceived susceptibility and severity and only utilizes the interaction term as the predictor of the outcome variables (Lu et al., 2020; Rimal & Real, 2003). In other words, the multiplicative model does not account for the main effect of susceptibility and severity perception. Differently, the current model highlights the conditional nature of severity perception’s effects and argues for a moderating role of susceptibility perception. The current setup thus does not preclude the possibility that severity and susceptibility perception may also have unique effects on people’s attitudes and behavior, as proposed in other models such as HBM (Janz & Becker, 1984).

Proposition 1 is of value to researchers and practitioners. It offers a contingency plan for communicating risks to people with different susceptibility to them. For low-susceptibility individuals (e.g., young people who are less susceptible to COVID-19’s negative consequences), highlighting the severity of the risk, such as the magnitude of the financial and physical loss, may be an effective strategy to promote attitude and behavioral change. Differently, for the highly susceptible ones, such as people living in flood-prone areas, emphasizing the severity of the threat may not be very effective in instigating actions.

Efficacy appraisal and disparity

In addition to threat appraisal, efficacy appraisal is another set of considerations that shape people’s responses to threats. In the traditional risk models, efficacy appraisal is usually operationalized as self and response efficacy, which characterize a person’s evaluation of their ability to access and utilize risk prevention and the prevention’s efficacy in averting the negative consequences of the threat (Witte, 1994). However, as illustrated earlier, not all people have equal access to effective risk prevention tools and strategies (i.e., resource disparity). For example, underserved individuals and communities such as racial and ethnic minorities, lower-income communities, and other marginalized groups often suffer more from environmental and health threats than their privileged counterparts (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015; Braveman et al., 2011). Therefore, it is important to recognize the role of accessibility to prevention resources in shaping people’s response to risks.

We argue that perceived accessibility of risk prevention may function similarly to a person’s perceived distance of prevention resources. Specifically, low perceived accessibility is associated with far psychological distance, and high accessibility perception corresponds with close psychological distance. First, access to risk prevention resources is often unequal across geographic and social boundaries. Research shows that people living in lower-income neighborhoods often have less access to critical resources such as healthy food and emergency aids than those living in the more affluent ones (Braveman et al., 2011). Additionally, underprivileged individuals tend to find support in their social networks during environmental and health hazards (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015). Second, disparity also exists in the temporal distribution of risk prevention resources. Less privileged individuals often experience a longer delay in accessing risk prevention tools such as vaccination and disaster aid (Sultan et al., 2014). Notably, such delay may result from factors in addition to infrastructural inequity. Due to historical reasons, distrust in resource providers such as governmental agencies may also prevent underprivileged individuals from timely access to risk prevention resources such as vaccines (Willis et al., 2021). Lastly, lower accessibility is also related to more uncertainty regarding access to critical risk prevention tools and strategies. In other words, people who perceive risk prevention resources as less accessible may also believe that they are less likely to receive such resources. In support of such a claim, studies show that the lack of accessibility to vaccines led to a more distant perception of such resources (Chu & Liu, 2021b).

Based on the theorization above, it is thus likely that perceived accessibility of risk prevention resources may function similarly to psychological distance to moderate the effects of high and low-level factors in shaping people’s response to different threats. The question now is what might be considered the high and low-level factors. We argue that response and self-efficacy are a dyad of such variables, where response efficacy represents a higher-level consideration of risk prevention and self-efficacy represents a low-level concrete consideration. First, response efficacy, which demarcates a person’s belief regarding a prevention’s ability to avert the obnoxious effects of the risk, is central to people’s mental construal of such a prevention tool or strategy. Self-efficacy, which is the belief about one’s ability to adopt such prevention resources, on the other hand, is subordinate to response efficacy. For example, an effective vaccine that is hard to get (e.g., a very costly vaccine) may still be considered useful prevention against diseases, but an easy-to-get vaccine that does not prevent any disease may not be considered a viable preventive tool. Second, response and self-efficacy are respectively associated with the desirability and feasibility of the prevention, a widely tested pair of high and low-level factors (Trope et al., 2007). As the goal of adopting a risk prevention resource is to reduce the likelihood and severity of the risk, more efficacious prevention is more likely perceived as desirable. Similarly, a more feasible risk prevention resource should enhance self-efficacy due to its ease of use and accessibility. Supporting such a claim, existing research found that perceived self-efficacy exerted stronger impacts on people’s intention to support climate change mitigation policies when close psychological distance cues were featured in messages (Chu & Yang, 2020). Synthesizing the reasoning above, we propose that response and self-efficacy’s influences on attitudes and behavior may be moderated by people’s perceived accessibility to risk prevention resources. Specifically, response efficacy may exert stronger impacts on people’s attitudes and behaviors when the perceived accessibility is low, but self-efficacy may have stronger effects when the perceived accessibility is high (Proposition 2).

The second proposition also offers insights into psychology and risk management research and practice. It provides a contingency plan for the communication of environmental and health risks to populations with different levels of accessibility to the prevention resource. For those who do not have full access to resources (e.g., countries waiting for a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine), highlighting its effectiveness in preventing or reducing the harm of threats may be more effective in preparing the group. Differently, for those with a sufficient supply of prevention tools and strategies, messages should emphasize the ease of use and availability of such resources to enhance self-efficacy.

The current study

In summary, various models have been proposed to address the influence of threat and efficacy appraisal on people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses to risks. The models often take an additive approach to configure the relationship between two sets of predictors, including threat and efficacy appraisals, and attitudinal and behavioral outcomes (Lu et al., 2020; Popova, 2012). Despite their popularity in applied research, the additive models do not account for the interactive effects between the key predictors, such as perceived severity and susceptibility of risks, leading to reduced explanatory power in situations where the two perceptions are incongruent (e.g., high-severity-low-susceptibility risks). The less-frequently utilized multiplicative model builds on the expectancy-value theory (Rimal & Real, 2003). While it addresses the interactive effects of severity and susceptibility perceptions, the model does not consider the main effects of the subdimensions of threat appraisal. In addition, existing models also fail to account for the influence of disparity in access to risk-prevention behaviors or resources. Though populations with underserved needs may have sufficient threat and efficacy appraisals, limited access to risk prevention and mitigation resources may also influence their attitudes and behaviors.

To address these gaps in research, we propose a Risk-Efficacy Framework (REF) that integrates classic risk-related psychological models such as PMT, HBM, and EPPM with the Construal Level Theory (CLT) of psychological distance (Trope & Liberman, 2010). The model postulates that perceived susceptibility to risks and accessibility to risk prevention resources may function as psychological distance and moderate the influences of central and peripheral features of risk and risk response on people’s attitudes and behaviors. Specifically, the model makes two propositions addressing the research gap identified above. First, we argue that perceived susceptibility moderates the effects of the perceived severity of risks, where severity perception’s effects on the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes attenuate with the increase of susceptibility perception. The moderation hypothesis incorporates both the additive and multiplicative configuration of threat appraisal dimensions and offers clarity in situations where severity and susceptibility perceptions are incongruent. Second, the model suggests that perceived accessibility to risk prevention resources moderate the influence of self and response efficacy. Specifically, self-efficacy’s influences on the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes are expected to increase with perceived accessibility, but response efficacy’s effects would decrease. The introduction of accessibility perception acknowledges the disparity in risk prevention resources. Notably, the effective integration of accessibility perception in the REF generates readily testable hypotheses and provides actionable plans for risk managers interacting with underserved communities. The conceptual clarity offered by REF contributes to the theoretical understanding of people’s response to risks and risk prevention resources. More importantly, it provides a dynamic plan for risk managers to address developing threats. As risks are never static, risk managers need to highlight different aspects of risks and prevention depending on how vulnerable the target population is and how much resource is available. We summarize the REF in Fig. 1.

We illustrate an empirical study that tests the proposed model. The study focuses on an ongoing risk, the COVID-19 pandemic, and one of its most effective prevention resources – the COVID-19 vaccines. As of March 2022, the pandemic has led to more than five million deaths worldwide. However, despite the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in reducing the harm of the disease, many were reluctant to receive a vaccine. The study, which took place right before the COVID-19 vaccines became widely available in the United States, investigates how threat and efficacy appraisal influence people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions related to the COVID-19 vaccines. Specifically, we test not only their intention to get vaccinated but also their support for policies related to the COVID-19 vaccines. As a risk for both individual persons and the whole society, the COVID-19 pandemic requires collective efforts to contain its health and economic damages. Therefore, the inclusion of policy support as an outcome variable not only captures the proposed models’ explanatory power of both individual and collective-level behavioral intention but also enhances its generalizability to other individual (e.g., HPV infection) and societal (e.g., climate change) risks.

Proposition 1 and 2 respectively hypothesize that perceived susceptibility to risks and perceived accessibility to risk prevention resources will moderate the effects of severity and efficacy perceptions on the attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. In order to empirically test the propositions, we proposed three sets of models with attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines, intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, and support for COVID-19 vaccine-related policies as the outcome variables.

Model 1A to 7A focuses on people’s attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine and the effects of the REF factors. Specifically, Model 1A serves as the baseline model predicting attitudes with existing vaccine history and demographics. Corresponding to Proposition 1, which argues that perceived susceptibility would moderate the effect of perceived severity, we contrasted Model 2A, which represents an additive configuration of severity and susceptibility perceptions, with Model 3A, which represents the interactive setup suggested by the REF. We hypothesize that severity and susceptibility perceptions will be positively related to positive attitudes toward the vaccines, and the interaction will be negatively related to the outcome variable, as the effects of severity perception would attenuate with susceptibility perception. Similarly, Model 4A and 5A test Proposition 2 concerning the attitudinal outcomes. Model 4A utilizes an additive approach to model efficacy appraisal and accessibility perception’s influence on attitudes, and Model 5A tests the hypothesis that accessibility perception moderates the effects of self and response efficacy. Based on Proposition 2, we expect that self and response efficacy will both be positively associated with positive attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine. Additionally, it is hypothesized the interaction between self-efficacy and accessibility perception will positively predict attitudes, but the interaction between response efficacy and accessibility perception will be a negative predictor of the outcome variable. Lastly, Models 6A and 7A concurrently assess Propositions 1 and 2. Model 6A builds on the additive configuration, and Model 7A includes the interactions tested in Model 3A and 5A. The hypothesized effects of the main effects and interactions are also consistent with the preceding models.

Models 1B to 7B resemble the same setup as Models 1A to 7A, but it focuses on individual behavioral intention to get vaccinated for COVID-19. Specifically, Model 1B is the baseline model without the REF factors. Models 3B to 5B test Propositions 1 and 2 individually against the additive configurations in Models 2B and 4B. Models 6B and 7B concurrently assess the predictive power of REF against an additive setup of the threat and efficacy appraisals. The directions of the hypothesized main effects and interactions are expected to remain consistent with Model 1A-7A illustrated above.

Model 1C to 7C focuses on support for COVID-19 vaccine-related policies as the outcome variable of the REF factors. Model 1C is the baseline model predicting policy support with demographic variables and vaccine history. Models 2C, 4C, and 6C are additive models, and Models 3C, 5C, and 7C are interactive models specified according to Propositions 1 and 2, individually and jointly. We expect that the main effects of the REF variables on policy support will be positive, and the interactive effects will vary. Specifically, the interaction between severity and susceptibility perceptions and the interaction between response efficacy and accessibility perception would be negatively associated with policy support. However, the interactive effect between self-efficacy and accessibility perception would be positive on policy support.

Method

Sample

Upon Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, a sample of participants with a demographic composition similar to the U.S. population was collected in October 2020 from Qualtrics online panels, two months before the first COVID-19 vaccine was authorized by the FDA. In total, 1,810 people opened the online survey hosted on Qualtrics.com. Among them, 729 provided informed consent, completed the survey questionnaire, and passed two attention check questions. The final sample (N = 729) consists of 370 participants who identified as female (50.8%) and 359 who identified as male (49.2%). No participants in the final sample identified as non-binary gender. The average age of the sample was 46.4 (SD = 17.2), and the median household annual income falls in the bracket between $50,000 and $74,999. The median education level is some college. The majority of the participants identified as non-Hispanic White (n = 444, 60.9%), followed by those who identified as Hispanic or Latino (n = 133, 18.2%) and Black or African American (n = 96, 13.2%). Asian, Pacific Islander, and Native American participants accounted for 6.0% of the sample (n = 44), and the other 1.6% identified as other race/ethnicity (n = 12). Three hundred fifty-six participants received some vaccine in the 18 months prior to taking the survey (48.8%), and 366 did not (50.2%). The other 7 participants were unsure if they had received a vaccine recently (1%).

Measurement

Threat appraisal

Perceived severity and susceptibility were each measured with three items (Brewer & Fazekas, 2007; Liu et al., 2021). Perceived severity measures include items such as “I believe that COVID-19 is a severe health problem” and “I believe that COVID-19 has serious negative consequences.” Sample susceptibility items include “It is likely that I will get COVID-19” and “I am at risk of getting COVID-19”. Participants indicated their agreement with the statements on a five-point Likert scale (1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly agree”). The scales are reliable (alpha = 0.72 for perceived severity and alpha = 0.74 for perceived susceptibility).

Efficacy appraisal

Response and self-efficacy are similarly measured with three items each (Gerend & Shepherd, 2012). Response efficacy items include “COVID-19 vaccines will work in preventing COVID-19” and “COVID-19 vaccines will be effective in preventing COVID-19.” Self-efficacy items include “I can easily get vaccinated to protect myself from COVID-19” and “I have the skill, time, and money to get vaccinated to avoid contracting COVID-19.” Participants responded to these items with the same five-point Likert scale. These scales are again reliable (alpha = 0. 78 for the self-efficacy scale; alpha = 0.86 for the response-efficacy scale). On average, participants perceived that the COVID-19 vaccines are effective in averting the negative impacts of the disease (M = 3.67, SD = 0.87), and they are efficacious in utilizing the vaccines (M = 3.41, SD = 0.91).

Perceived accessibility

Unlike the threat and efficacy appraisal scales, perceived accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines was measured by a single item (“A COVID-19 vaccine will likely be available to people like me.”). The single-item measure was adopted for two reasons. First, as the disparity in people’s access to risk prevention resources often exists due to inequity among social groups, measuring one’s perception of COVID-19 vaccines accessibility for themselves and people like them most accurately captures such disparity. Second, as there is no existing scale for such a variable, the single-item measure provides a starting point for the development of larger scales. With that being said, we recommend that future research may expand on the current measurement scheme and incorporate additional items for the variable.

Attitudes and behavioral intention

Three outcome variables were measured to assess the explanatory power of the proposed model. The first variable is attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines (Liu et al., 2021), which were assessed with five semantic differential items (e.g., 1 “negative” to 5 “positive”, 1 “bad” to 5 “good”). The scale is reliable (alpha = 0.96). The second variable measures participants’ intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine when it is available (Chu & Liu, 2021a). Sample items include “I would consider getting a COVID-19 vaccine” and “I would actually get vaccinated for COVID-19.”). Response to this scale is recorded with a five-point Likert scale (1 “Very unlikely” to 5 “Very likely”). The items achieved satisfactory reliability (alpha = 0.95). Lastly, support for COVID-19-vaccine related policies was assessed with four policy items such as “Fund more research into COVID-19 vaccines” and “Expand Medicaid coverage to help uninsured people get vaccinated for COVID-19”. Responses to these items were recorded with a five-point scale (1 “Strongly disagree” to 5 “Strongly disagree”). The scale is again reliable (alpha = 0.76).

Results

In general, our participants perceived COVID-19 as a severe threat (M = 3.96, SD = 0.92) to which they are relatively susceptible (M = 3.19, SD = 0.90). Participants also perceived that the COVID-19 vaccines would likely be available to people like them (M = 3.77, SD = 0.89). As for the outcome variables, participants, on average, showed positive attitudes toward the vaccines (M = 3.85; SD = 1.25), were willing to be vaccinated (M = 3.68; SD = 1.33), and indicated relatively strong support for COVID-19 vaccine-related policies proposals (M = 3.70; SD = 0.86). Visual inspection of the distribution of the variables also indicates there was no particular outlier in any of the variables.

As illustrated earlier, we employed a set of 21 OLS regression models with attitudes, behavioral intention, and policy support as the outcome variables (Tables 1, 2, and 3). All variables utilized to create an interaction term were mean-centered to avoid multicollinearity (VIFs < 2). Demographic variables and vaccination history were included in the models as control variables. Research shows that previous vaccination history is one of the most effective indicators of people’s intention to receive a new vaccine (Dubé et al., 2015). Vaccination history was a consistent predictor of all three outcome variables. People who have received a vaccine were more likely to hold a positive attitude toward the vaccine, get vaccinated, and support COVID-19 vaccine policies. Age and education were also significant predictors of attitudes and behavioral intention, but only education was a significant predictor of policy support. Female participants also showed more negative attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccines (Model 1A-1C).

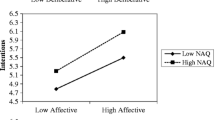

Proposition 1 predicts that perceived severity and susceptibility interact to influence people’s attitudes and behaviors. Congruent with extant models, both subdimensions of the threat appraisal were consistent predictors of people’s attitude toward COVID-19 vaccines, intention to adopt the vaccine, and support for COVID-19 vaccine-related policies (Model 2A-2C). Those who believe that COVID-19 is a severe threat and likely to influence their health were more likely to think favorably of the vaccine, get the vaccine, and support policies promoting it. Congruent with Proposition 1, we also found that severity and susceptibility perception interacted to influence the outcome variables (Model 3A-3C). The interaction term further indicates that the effects of severity perception on all the outcome variables decreased when perceived susceptibility was high. Therefore, Proposition 1 was supported.

Similar regression models were utilized to test the effects of self and response efficacy conditioned by the perceived accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines (Tables 1, 2, and 3). Response efficacy was a predictor of all three outcome variables. However, self-efficacy was only a significant predictor of behavioral intention and policy support. Perceived accessibility of COVID-19 vaccines, on the other hand, was not a significant predictor of the outcome variables (Model 4A-4C). However, perceived accessibility interacted with self-efficacy to predict behavioral intention and policy support, as Proposition 2 predicts. In particular, self-efficacy’s positive influence on people’s intention to get vaccinated and support COVID-19 vaccine-related policy increased when they believed that vaccines were more accessible (Model 5B-5C). Congruent with Proposition 2, perceived accessibility also interacted with response efficacy to influence policy support, inasmuch as response efficacy’s positive influence on the dependent variable decreased when perceived accessibility was high (Model 5C). Therefore, Proposition 2 was largely supported by our data.

Lastly, we combined the regression models to examine if the interactive effects held when all variables were included in the model (Model 7A-7C). The interaction between susceptibility and severity perception and the interaction between perceived accessibility and self-efficacy were significant predictors of policy support. The directions of their effects were also congruent with our predictions.

Discussion

As illustrated earlier, recent health psychology and communication research has demonstrated an increasing focus on the interplay of cognitive appraisal processes, such as threat and efficacy, in shaping health-related attitudes and behaviors (Chu & Liu, 2021a; Lu et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2016). However, these studies often overlook the role of resource accessibility, specifically, the disparity in access to risk prevention resources (e.g., Roberto & Zhou, 2023; Ruiz & Bell, 2021). This gap becomes even more salient in the context of a global health crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, where disparities in resource accessibility can significantly impact health outcomes. The current study aims to address this gap by proposing a Risk-Efficacy Framework that integrates existing theories, such as EPPM, HBM, and CLT (Popova, 2012; Trope & Liberman, 2010; Witte & Allen, 2000). This framework offers a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of how threat and efficacy appraisals, coupled with resource accessibility, can influence individuals’ attitudes and behaviors toward disease prevention. As demonstrated above, the novelty of our study lies in empirically testing these variables and uncovering their moderating effects, such as how perceived susceptibility moderates perceived severity’s influence on attitudes and behaviors. Furthermore, we revealed that accessibility to risk prevention resources could moderate self and response efficacy’s impact. These findings enrich the dynamic understanding of risk in health communication, providing valuable insights for risk management and public health campaign design, particularly for underserved populations. In the following section, we discuss the findings and their implications in greater depth and provide practical suggestions for practitioners designing and implementing health interventions targeting different populations.

Corresponding to our first proposition, we found that perceived severity and susceptibility interacted with perceived severity to influence people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions. The inclusion of the interaction term, on average, led to a 1.3% increase in the models’ ability to explain the variance in the outcome variables. Such findings suggest that severity perception’s effects may be conditioned on the perceived probability of the threat occurring (i.e., perceived susceptibility). People may be more likely to consider taking action against a threat, such as getting vaccinated, when they believe that they are not very susceptible to the threat and the threat may lead to severe damage. Differently, an imminent and severe threat may not lead to positive attitudes toward prevention resources and an intention to adopt such resources. At first glance, such findings may seem contradictive to propositions made by earlier models such as the EPPM, which highlights the importance of threat appraisal in motivating attitudinal and behavioral change (Witte, 1992). However, we argue that it actually complements EPPM and other models’ propositions. Specifically, EPPM argues that overly threatening information (i.e., high-threat appraisal) paired with low efficacy appraisal may lead to strong fear, which inhibits attitudinal and behavioral change due to the subsequent fear-control process (Witte, 1994). Our proposition is congruent with such an argument and provides additional nuances to the effects of threat appraisal dimensions. We argue that heightened severity perception may be less conducive to attitudinal and behavioral change when perceived susceptibility is also high, but its positive effects should remain when people do not believe they are very susceptible to the threat.

Our findings also supported the key role of accessibility in determining people’s behavioral intentions in the face of a threat. Self-efficacy played a more important role when people believed they had access to prevention resources, but response efficacy’s explanatory power was more substantial when perceived accessibility was low. Such findings indicate that campaigns promoting risk prevention tools and strategies such as vaccines should customize their messages based on the disparity in audience access to the resources. Highlighting the effectiveness of the resource may be more effective in promoting actions among low-access groups. Differently, emphasizing one’s ability to access and utilize the resource may be more effective for the high-accessibility groups. Notably, response efficacy was the only significant predictor of attitudes toward the vaccine, which may be due to the conceptual similarity between these two variables. Indeed, thinking positively about a vaccine is similar to considering the vaccine as an effective tool to combat the disease due to response efficacy’s central role in shaping people’s construal of it.

Specific findings from Model 1A to 7C are also worth noting. Results of Model 1A to 1C indicate that vaccine history, age, and education were consistent predictors of people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses related to the COVID-19 vaccines. Consistent with existing research, educated and older individuals as well as those who recently received a vaccine showed more favorable attitudes toward the vaccine and were more likely to get vaccinated or support vaccine-friendly policies (Chu & Liu, 2021a; Ruiz & Bell, 2021). Such findings highlight the importance of personal experience and background in vaccine promotion.

Results of Models 2A-2C and 3A-3C were congruent with the relationship hypothesized in Proposition 1, showing that the interaction between severity and susceptibility perception increased the model’s predictive power of people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions, above and beyond their main effects. As illustrated earlier, existing research mostly utilized the additive configuration of severity and susceptibility perceptions (Lu et al., 2020; Ruiz & Bell, 2021). Our findings offered more nuances into the relationship between the two subdimensions of threat appraisal on the outcome variables. Differently, Models 4A-4C and 5A-5C yielded less consistent results concerning Proposition 2. The interactions between accessibility perception and the two efficacy appraisal dimensions were only significantly associated with policy support but not attitudes and vaccination intention. Specifically, self-efficacy’s positive effects on policy support increased as perceived accessibility increased, but response efficacy’s positive effects attenuated with accessibility perception. One possible reason behind such a discrepancy is that policy support may be more sensitive to the moderating effects of accessibility perception due to its relevance to collective health decision-making. As attitudes and vaccination intention focus more on individual well-being, which tends to be more concrete than collective decision-making (Gualano et al., 2019), it is likely that accessibility perception’s conditioning effects, which realize through the corresponding variation in construal level, may not be as salient. Notably, The main effects identified in Models 4A-4C and 5A-5C (i.e., the positive effects of self and response efficacy and accessibility perception on attitudes and behavioral intentions) were congruent with existing research (Chu & Liu, 2021a; Shmueli, 2021).

Models 6A to 7C concurrently assessed Propositions 1 and 2. Similar to Models 4A-4C, the results of the additive models (Models 6A-6C) were consistent with existing research (Roberto & Zhou, 2023). However, only Model 7C identified all the significant interactions hypothesized in Propositions 1 and 2. In addition to the possible differences between individual and collective decision-making illustrated above, we suspect that the incongruent findings in Models 7A and 7B may be due to the strong association of response efficacy with attitudes and vaccination intention. Previous research suggests that perceiving a vaccine as highly efficacious (i.e., high response efficacy) is often related to individual perception of the vaccine and intention to receive it (Davis et al., 2022). Thus, such a variable may have taken the lion’s share in explaining people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions regarding the COVID-19 vaccines while suppressing the effects of the other variables. Nevertheless, results from the 21 models in the current study complement existing research findings. More importantly, they demonstrate that the REF provides additional explanatory power, especially regarding behavioral intention at the collective level (i.e., policy support).

Findings from the empirical test examining the predictive power of the REF in conjunction with the classic additive models contribute to our theoretical understanding of psychological factors underlying people’s risk-related attitudes and behavioral intentions. They also offer some valuable contributions to the practice of risk management. From the theoretical perspective, it provides more nuanced insights into the effects of threat and efficacy appraisals in predicting people’s attitudinal and behavioral responses to risks. The model also accounts for the influence of disparity in people’s access to risk prevention resources, which has received increasing attention from researchers and practitioners in the recent decade (Chu & Liu, 2021b; Tatar et al., 2021). Specifically, severity perception’s effects attenuated along with the increase of susceptibility perception, indicating that the effects of these two threat appraisal dimensions are not independent. Instead, susceptibility conditions the influence of severity perception. Additionally, higher accessibility perception also amplified the effect of self-efficacy but reduced the effect of response efficacy on policy support. Such findings showcased the dynamic nature of efficacy appraisal’s influence on people’s risk decision-making, especially at the collective level.

The major practical contribution of the current study also centers on its dynamic and developmental view of risks and risk prevention. At the early stage of risk, such as when COVID-19 was first detected, highlighting the severity of its impacts may better motivate people to form a positive view of the risk prevention resources and adopt the prevention tools. However, as the risks further develop and become imminent, emphasizing the severity of their threat may be less effective. Additionally, as the availability of risk prevention resources such as vaccines varies geographically and temporally, risk managers need to use caution when communicating with populations with different access to these resources. Highlighting the effectiveness of prevention tools such as vaccines may be more beneficial for those without an abundant supply of such resources. However, risk communication campaigns need to focus on individuals’ ability to utilize these tools to overcome the risk (i.e., self-efficacy) when accessibility is high.

Limitations

The current study also has its limitations. First and foremost, no message was experimentally tested. Therefore, we need to use caution when making causal claims regarding the relationships reported above. As an initial test of the Risk-Efficacy Framework, the current study builds a foundation for more robust tests of the model’s explanatory and predictive power. We recommend that future research utilizes an experimental design to examine the model. Second, fear was not measured or manipulated in the current study. As an integral component of models such as EPPM, discrete emotions such as fear play an important role in shaping people’s response to risk communication messages (Popova, 2012). Though we took a similar approach as Rogers (1975) to focus on the cognitive side of people’s response to risks, the inclusion of fear or other discrete emotions may further enhance the model’s ability to aid risk communication design. Third, the single-item measure of perceived accessibility, as noted earlier, may limit the reliability of such a key item. We utilized a single-item measure to avoid fatigue in participants and reduce the cognitive load to assess one’s accessibility perception. However, despite its satisfactory face and concurrent validity, we highly recommend that future studies may expand on the current measurement and include additional items to measure the construct. Lastly, it is also notable that the COVID-19 vaccines were not widely available in the United States when this study was conducted. The media portrayal of them largely influenced people’s perception of the vaccines. It is thus necessary to replicate our study in other contexts, such as risks with available prevention resources.

Conclusion

A Risk-Efficacy Framework that reorganizes the subdimensions of threat and efficacy appraisal and accounts for the influence of disparity in people’s access to risk prevention resources was proposed. We argue that the perceived severity of a threat may lead to a stronger influence on people’s response to a threat when perceived susceptibility to the threat is lower. Findings from a survey study on COVID-19 vaccines supported such an argument. Additionally, the model suggests that response efficacy may weigh more in shaping people’s response to a less accessible risk prevention resource, but self-efficacy’s effects may be more salient when the perceived accessibility is high. Our findings again supported such a proposition. The proposed model offers a new perspective on understanding people’s consideration of different environmental and health threats. More importantly, it provides a viable plan for risk communication campaigns targeting the public with different characteristics. For those who believe that a risk is less imminent, communicators may instigate more attitudinal and behavioral change by highlighting the severity of the risk. However, such a strategy may not be very effective for those who already think about the risk as a high-probability event. Furthermore, when communicating with groups with less access to risk prevention resources, such as those waiting for a new medication, it may be an effective strategy to articulate the prevention’s effectiveness in averting the negative effects of the risks and keep up the groups’ enthusiasm. Differently, improving people’s self-efficacy may be more conducive to behavioral change when the risk prevention resources are more accessible.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adler, S., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). Mapping the jungle: A bibliometric analysis of research into construal level theory. Psychology & Marketing, 38(9), 1367–1383.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Aldrich, D. P., & Meyer, M. A. (2015). Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 254–269.

Atkinson, J. W. (1964). An introduction to motivation. Van Nostrand.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

Bar-Anan, Y., Liberman, N., Trope, Y., & Algom, D. (2007). Automatic processing of psychological distance: Evidence from a Stroop task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 136(4), 610.

Braveman, P. (2006). Health disparities and health equity: Concepts and measurement. Annual Review of Public Health, 27, 167–194.

Braveman, P. A., Kumanyika, S., Fielding, J., LaVeist, T., Borrell, L. N., Manderscheid, R., & Troutman, A. (2011). Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. American Journal of Public Health, 101(S1), S149–S155.

Brewer, N. T., & Fazekas, K. I. (2007). Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: A theory-informed, systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 45(2–3), 107–114.

Chaiken, S. (1980). Heuristic versus systematic information processing and the use of source versus message cues in persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 752.

Chu, H., & Liu, S. (2021a). Integrating health behavior theories to predict American’s intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(8), 1878–1886.

Chu, H., & Liu, S. (2021b). Light at the end of the tunnel: Influence of vaccine availability and vaccination intention on people’s consideration of the COVID-19 vaccine. Social Science & Medicine, 286, 114315.

Chu, H., & Yang, J. Z. (2020). Risk or efficacy? How psychological distance influences climate change engagement. Risk Analysis, 40(4), 758–770.

Davis, C. J., Golding, M., & McKay, R. (2022). Efficacy information influences intention to take COVID-19 vaccine. British Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 300–319.

Dubé, E., Vivion, M., & MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy, vaccine refusal and the anti-vaccine movement: Influence, impact and implications. Expert Review of Vaccines, 14(1), 99–117.

Gerend, M. A., & Shepherd, J. E. (2012). Predicting human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in young adult women: Comparing the health belief model and theory of planned behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 44(2), 171–180.

Goodman, J. K., & Malkoc, S. A. (2012). Choosing here and now versus there and later: The moderating role of psychological distance on assortment size preferences. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 751–768.

Gore, T. D., & Bracken, C. C. (2005). Testing the theoretical design of a health risk message: Reexamining the major tenets of the extended parallel process model. Health Education & Behavior, 32(1), 27–41.

Griffin, R. J., Dunwoody, S., & Neuwirth, K. (1999). Proposed model of the relationship of risk information seeking and processing to the development of preventive behaviors. Environmental Research, 80(2), S230–S245.

Gualano, M. R., Olivero, E., Voglino, G., Corezzi, M., Rossello, P., Vicentini, C., ..., & Siliquini, R. (2019). Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs towards compulsory vaccination: a systematic review. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 15(4), 918–931.

Janz, N. K., & Becker, M. H. (1984). The health belief model: A decade later. Health Education Quarterly, 11(1), 1–47.

Lang, A. (2000). The limited capacity model of mediated message processing. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 46–70.

Lattimore, P. J., & Halford, J. C. (2003). Adolescence and the diet-dieting disparity: Healthy food choice or risky health behaviour? British Journal of Health Psychology, 8(4), 451–463.

Liu, S., Yang, J. Z., & Chu, H. (2021). When we increase fear, do we dampen hope? Using narrative persuasion to promote human papillomavirus vaccination in China. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(11), 1999–2009.

Lu, H., Group, A. A., Winneg, K., Jamieson, K. H., & Albarracín, D. (2020). Intentions to seek information about the influenza vaccine: the role of informational subjective norms, anticipated and experienced affect, and information insufficiency among vaccinated and unvaccinated people. Risk Analysis, 40(10), 2040–2056.

Mumm, J., & Mutlu, B. (2011). Human-robot proxemics: physical and psychological distancing in human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI). Lausanne, Switzerland.

Popova, L. (2012). The extended parallel process model: Illuminating the gaps in research. Health Education & Behavior, 39(4), 455–473.

Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Perceived risk and efficacy beliefs as motivators of change: Use of the risk perception attitude (RPA) framework to understand health behaviors. Human Communication Research, 29(3), 370–399.

Roberto, A. J., & Zhou, X. (2023). Predicting college students’ COVID-19 vaccination behavior: An application of the extended parallel process model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1–2), 76–87.

Rogers, R. W. (1975). A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change1. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 93–114.

Ruiz, J. B., & Bell, R. A. (2021). Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine, 39(7), 1080–1086.

Shmueli, L. (2021). Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13.

Slovic, P., Fischhoff, B., & Lichtenstein, S. (1981). Rating the risks. In Risk/benefit analysis in water resources planning and management (pp. 193–217). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2168-0_17

Spence, A., Poortinga, W., & Pidgeon, N. (2012). The psychological distance of climate change. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 32(6), 957–972.

Stephan, E., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2010). Politeness and psychological distance: A construal level perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 268.

Sultan, D. H., Norris, C. M., Avendano, M., Roberts, M., & Davis, B. (2014). An examination of class differences in network capital, social support and psychological distress in Orleans Parish prior to Hurricane Katrina. Health Sociology Review, 23(3), 178–189.

Tannenbaum, M. B., Hepler, J., Zimmerman, R. S., Saul, L., Jacobs, S., Wilson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2015). Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological Bulletin, 141(6), 1178.

Tatar, M., Shoorekchali, J. M., Faraji, M. R., & Wilson, F. A. (2021). International COVID-19 vaccine inequality amid the pandemic: Perpetuating a global crisis? Journal of Global Health, 11. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.03086

Todorov, A., Goren, A., & Trope, Y. (2007). Probability as a psychological distance: Construal and preferences. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43(3), 473–482.

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440.

Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 83–95.

Willis, D. E., Andersen, J. A., Bryant-Moore, K., Selig, J. P., Long, C. R., Felix, H. C., Curran, G. M., & McElfish, P. A. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clinical and Translational Science, 14(6), 2200–2207.

Witte, K. (1992). Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communications Monographs, 59(4), 329–349.

Witte, K. (1994). Fear control and danger control: A test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM). Communications Monographs, 61(2), 113–134.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615.

Xu, X., Yang, M., Zhao, Y. C., & Zhu, Q. (2020). Effects of message framing and evidence type on health information behavior: the case of promoting HPV vaccination. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 73, 63–79.

Xue, W., Hine, D. W., Marks, A. D., Phillips, W. J., Nunn, P., & Zhao, S. (2016). Combining threat and efficacy messaging to increase public engagement with climate change in Beijing. China. Climatic Change, 137(1), 43–55.

Yang, J. Z., & Chu, H. (2018). Who is afraid of the Ebola outbreak? The influence of discrete emotions on risk perception. Journal of Risk Research, 21(7), 834–853.

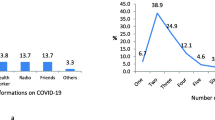

Yang, J. Z., Liu, Z., & Wong, J. C. (2022). Information seeking and information sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Communication Quarterly, 70(1), 1–21.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Haoran Chu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization; Sixiao Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, H., Liu, S. Risk-efficacy framework – a new perspective on threat and efficacy appraisal and the role of disparity. Curr Psychol 43, 5999–6012 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04813-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04813-9