Abstract

Using a community-based participatory research approach, we conducted a survey of 218 food pantry recipients in the south Bronx to determine predictors of food insecurity and childhood hunger. In adjusted multiple regression models, statistically significant risk factors for food insecurity included: having one or more children and not having health insurance. Statistically significant protectors against childhood hunger were: having a graduate degree, having health insurance and Spanish being spoken at home. Experiencing depression symptoms was positively associated with both food insecurity and childhood hunger. Frequency of food pantry use was not significantly associated with either food insecurity nor childhood hunger. This study suggests that targeting families with multiple children and without insurance will best help to promote food security among residents of the south Bronx. Social policy implications related to food security and benefit provision through the COVID-19 pandemic are also provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Defining Food Insecurity

Defined by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO, 2006) as the lack of availability, accessibility, utilization, and stability of food, food insecurity can be interpreted to not only refer to uncertain or inconsistent access to food, but also to the psychosocial stress experienced by individuals and families who worry about having insufficient resources to provide nutritionally balanced meals to their households (Platkin et al., 2020). Food insecurity is a major public health problem linked to adverse health and mental health outcomes across the lifespan, impacting infants (Cook et al., 2006), children, women of childbearing age (Olson, 1999), adults (Stuff et al., 2004), and the elderly (Lee & Frongillo, 2001). Less severe food insecurity may result in coping behaviors, such as borrowing money for food, obtaining food from food banks, churches or nonprofit organizations, or reducing the variety and quality of diet ( & Kerrebrock, 1997). More severe food insecurity results in discomfort, pain or malnutrition caused by experiences of hunger due to inadequate food resources (Lewit & Kerrebrock, 1997).

Food insecurity is the historical result of structural, social and economic inequities that have been enhanced by the precarious conditions of food production and commercialization (Pereira & Oliveira, 2020). At the time of data collection for the present study, between 720 and 811 million people globally faced hunger in 2020 (UN FAO, 2001). Approximately 660 million people may still face hunger in 2030, partly due to the lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on global food security– 30 million more people than in a scenario in which the pandemic had not occurred (UN FAO, 2001). Although rates of food insecurity have consistently been rising in the United States (US), the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a substantial rise in food insecurity (Hu, 2022; Zack et al., 2021). Prior to the pandemic, food insecurity routinely affected approximately 11 to 12% of households in the US (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2019). In 2014, 19.2% of households with children were classified as food insecure as compared to 15.8% of households in 2007 (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2014).

In March/April 2020, national estimates of food insecurity doubled to 38% (Fitzpatrick et al., 2021). For US households with children, food insecurity at least doubled, if not tripled, from pre-pandemic levels (Ahn & Norwood, 2021; Hetrick et al., 2020). According to the most recent national estimates, 33.8 million people lived in food-insecure households with 8.6 million adults living in households with very low food security (United States Department of Agriculture, 2022). Additionally, 5.0 million children lived in food-insecure households in which both children and adults are food insecure (United States Department of Agriculture, 2022).

Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Food Insecurity

Black and Hispanic/Latinx households in the United States consistently experience higher rates of food insecurity compared to white and Asian households (Coleman-Jensen et al., 2014; Hu, 2022; Morales et al., 2021; Nam et al., 2015; Seligman & Berkowitz, 2019; Walsemann et al., 2017). In a national survey conducted in March 2020 among adults with incomes less than 250% of the federal poverty level, 44% of all households were food insecure, including 48% of Black households, 52% of Hispanic/Latinx households, and 54% of households with children (Wolfson & Leung, 2020a). In a second national web-based survey conducted between June and July 2020, 43% of adults with incomes below 250% of the federal poverty level continued to experience food insecurity (Wolfson & Leung, 2020b). Among households where an adult had lost a job or income, 59% were food insecure; among households in which more than one person lost a job or income, 72% were food insecure (Wolfson & Leung, 2020b).

Across the State of New York, approximately one in ten, or about 800,000, New York households experienced food insecurity at some point between 2019 and 2021 (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2023). In New York City (NYC) in 2018, approximately 615,000 adult residents (about 9%) reported that they sometimes or often did not have enough food to eat, ranging from as low as 4% among white New Yorkers to as high as 18% among Latinx New Yorkers (NYC Health, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic had direct implications for escalating these rates. In 2021, the estimated number of food insecure New Yorkers was approximately 1.4 million people (NYC Food Policy, 2021). Food insecurity has surged 36% citywide since the beginning of the pandemic (City Harvest, 2022). Compared with white New Yorkers (19%), Latinx (38%) and Black (35%) New Yorkers were almost twice as likely to report having less access to emergency food services due to COVID-19 (NYC Health, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic in NYC has disproportionately affected the boroughs that already had the greatest pre-pandemic rates of food insecurity. Compared to other New Yorkers, Bronx residents have historically experienced heightened food insecurity. Current estimates indicate that 16.4% of Bronx residents are now food insecure (Gundersen et al., 2021). In 2018, 251,180 people in the Bronx were food insecure, a rate substantially higher than the national average of 11.5% (Feeding America, 2020)). Out of New York State, the Bronx had the highest county rate for food insecurity at approximately 22% (United Hospital Fund, 2021a). One in four residents in the Bronx faces food insecurity, a rate 1.7 times the state average ((United Hospital Fund, 2021b). In the Bronx and Brooklyn, one in five children experienced food insecurity in the months following the emergence of COVID-19, compared to a rate of one in seven in Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island (Bufkin & Kimiagar, 2020). These rates are coupled with other structural inequities in the Bronx. Compared to other boroughs of NYC, the Bronx residents had the lowest median household income and were also more likely to experience barriers in accessing health care (Sullivan et al., 2021).

Childhood Hunger

A subcategory within food insecurity is childhood hunger, which refers to an inadequate amount of food intake of children, due to insufficient economic, family, or community resources (Briefel & Woteki, 1992). It is estimated that 8% of children under the age of 12 in the United States experience hunger and that an additional 21% are at risk for hunger, with hunger being most prevalent in children from the lowest income families (Wehler et al., 1996). One in four or almost 462,000 children in New York City are currently experiencing food insecurity, a 46% increase over pre-pandemic periods (City Harvest, 2022).

This rise in food insecurity has also been met with a rise in utilization of food benefits and emergency food services. As of December 2022, nearly 2.9 million households in New York State were enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the nation’s largest domestic food and nutrition program (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2023). Visits to New York City food pantries and soup kitchens rose 69% in 2022 as compared to 2019; food pantry access rates were up 14% just since January 2022 when inflation costs led to soaring food costs (City Harvest, 2022). By October 2020, one in three New Yorkers (34%) reported using emergency food services in the last 30 days, up from 22% in April 2020. (NYC Health, 2021).

Food insecurity has previously been linked to decreased immune function and higher rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health disorders (Althoff et al., 2016; Berkowitz et al., 2018a; Gundersen & Ziliak, 2015). Among children, food insecurity has been negatively associated with early childhood development; has been linked to poor vocabulary and math skills; and has been marginally associated with school readiness, reading, and motor development (de Oliveira et al., 2020). Children from homes that were persistently food insecure were more likely to have internalizing and externalizing problems compared with children from households that were never food insecure (Slopen et al., 2010). As millions of Americans struggle to afford food and housing, existing health disparities have widened through the pandemic (Wolfson & Leung, 2020b). In the United States, food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with a 257% higher risk of anxiety and a 253% higher risk of depression (Fang et al., 2021).

Study Objective

To address the local crisis of food insecurity in NYC, many nonprofit and human services organizations have dramatically increased their anti-hunger programs and shifted resources to provide food to the communities they serve through the pandemic (Bufkin & Kimiagar, 2020). In NYC exponential increases in visitors to food pantries and soup kitchens during the pandemic have been driven primarily by first-time visitors (91% increase) and families with children (79% increase; Food Bank for New York City, 2020). The unmet need among immigrant families is especially acute, due in part to undocumented residents and mixed-status families being excluded from several federal COVID-19 relief efforts (Bufkin & Kimiagar, 2020) and SNAP eligibility requirements. While Bronx residents have experienced heightened food insecurity and the highest death rates of COVID-19 per capita of the New York boroughs, research on food insecurity in the Bronx during the COVID-19 pandemic has been minimal (Sullivan et al., 2021). This project addresses this gap in the extant research by focusing on this marginalized population. In light of the heightened food insecurity issues during the COVID-19 pandemic, the goal of this study was to determine predictors for food insecurity and childhood hunger among a sample of food pantry recipients in the south Bronx.

Method

Research Setting

This project was a collaboration between a community-based organization (CBO), BronxWorks, and an interdisciplinary team of students and researchers from the Fordham Graduate School of Social Service (GSS) and the Fordham College at Rose Hill Honors Program. BronxWorks is a human service organization founded in 1972 that currently serves upwards of 50,000 Bronx residents per year. BronxWorks provides a number of social services, including adult and family homeless services; benefit assistance; chronic illness and healthcare management; education and youth development; eviction services; health and wellness services; immigration services; services for older adults; supportive housing; and workforce development.

Through the pandemic, BronxWorks reallocated resources to expand food pantry services. The focus of this study was BronxWorks’ Carolyn McLaughlin site, named in honor of the social worker who led BronxWorks for 34 years. Since the onset of the pandemic, the CBO has experienced a significant increase in demand for food assistance, with more than 250 families accessing their services on a weekly basis at the Carolyn McLaughlin site alone. Given that individuals and families experiencing food insecurity often do not have the resources to meet other basic needs (Wight & Thampi, 2010), BronxWorks instituted a program over the summer of 2021 to engage food pantry service recipients with wraparound services, including benefits screening, financial counseling, health insurance enrollment, immigration services, workforce development/job training, English as Second Language (ESL) classes, emergency crisis assistance, and housing assistance/eviction prevention.

Methodological Approach

The present study applies a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach (Israel et al., 1998) to identify emerging community needs of Bronx residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. CBPR emphasizes partnership building, community strengths and resources, and an emphasis on the development of a collaborative, equitable partnership through all phases of research (Israel et al., 2017). CBPR can be applied to learn about the contextual factors influencing community needs and assets in effectively addressing food insecurity (Jarrot et al., 2019). Before initiating the study, we held a series of meetings with researchers, BronxWorks leadership and other Bronx-based community stakeholders to identify community-driven research priority areas of inquiry. Through these discussions, a number of social issues arose as salient concerns for Bronx residents, including food insecurity, housing instability, and concerns regarding COVID-19 infection. After several community meetings, the group decided to focus on food insecurity for the community-driven focus of the project.

Study Design

Following community discussions, the group identified the goal of the present study to be to characterize the population using food pantry services during the COVID-19 pandemic and to determine predictors of food insecurity and childhood hunger through the use of a cross-sectional, quantitative study. As outlined by Schulz et al. (2005), we applied CBPR approaches to survey design and implementation. Academic partners contributed knowledge regarding peer-reviewed literature and validated scales of measurement while community partners incorporated valuable insights regarding community needs and dynamics. Community stakeholders were ultimately involved in the review, selection, and design of survey questions with the intention of maximizing usefulness for food pantry recipients in the Bronx. Surveys collected information about sociodemographic variables known or hypothesized to be associated with food security and childhood hunger, including age, income, education, employment status, number of people in the household, number and ages of children, and English language proficiency.

Recruitment and Eligibility

Using convenience sampling, survey respondents were recruited from a food pantry site in the Concourse neighborhood of the south Bronx. Recipients of food pantry services were explained the study when they visited the food pantry site. People interested in the survey were asked to schedule an appointment with a member of the research team. Additionally, individuals who were “walk ins” to the food pantry on Saturday mornings were also screened for study eligibility and immediate survey participation. Eligibility criteria included: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) Bronx residency, (3) recipient of food pantry services at BronxWorks, and (4) representing a single household. Following a participatory approach towards data collection, after the completion of each day of data collection, the research team met to debrief their process and to identify any necessary modifications to the next round of recruitment.

Sampling Procedures

We surveyed 218 food pantry service recipients in the south Bronx about their experiences of food insecurity, food pantry use, attitudes towards other social services offered by the CBO, and barriers and facilitators to service utilization. The research team was composed of staff and leadership from BronxWorks, as well as an interdisciplinary group of students and researchers from Fordham University. Research staff verbally explained the survey to potential participants. Potential study participants were approached by research staff, who were on-site at the food pantry location on Saturday mornings. Interested and eligible participants were asked to participate in a 20-minute survey, conducted by research staff in person, on tablets, using the online survey platform Qualtrics. The survey was also fully translated into Spanish and verified for accuracy with three native speakers of Spanish. Spanish-speaking food patrons were surveyed by Spanish-speaking students or by one of the study investigators. Because there were varying levels of literacy and digital literacy amongst the population, participants were read questions aloud in either English or Spanish from the tablet and were asked to answer questions about their experiences with food insecurity and obtaining food pantry services. The research staff member completing the survey entered the participant’s answers onto the Qualtrics form. Given the sensitive nature of some of the questions and how participants may feel apprehensive about answering questions out loud, we ensured that interviews were conducted in private, confidential locations at the food pantry site. Participants were compensated with a $20 Visa gift card for their survey participation. Data collection occurred between July 2021 and October 2021.

Measures

The survey included a brief series of sociodemographic questions, including age (18–30 years, 30–50 years, 50–70 years, above 70 years); race (White, Black/African American, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander); ethnicity (Hispanic/Latinx or not Hispanic/Latinx); country of birth; religion (Christianity, Islam, all others); education (high school degree or less, some college, Bachelor’s or graduate degree); gender; sex assigned at birth; sexual orientation; employment status (employed full-time, employed part-time, student, disabled, retired, unemployed); annual income (less than $10K, $10-$20K, $20-$30K, $30-$40K, over $40K); language spoken at home (English, Spanish, Others); disability status; household size; number of children in household; past COVID-19 diagnosis; past COVID-19 symptoms; knowing someone who had died from COVID-19; and COVID-19 vaccination status.

Food insecurity. The validated scale used to measure food insecurity was the U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) (United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2012; Blumberg et al., 1999). The HFSSM is composed of six items (USDA, 2012). The short form for households with children is sensitive (85.9%) and specific (99.5%) to determine overall food security (Blumberg et al., 1999). The HFSSM uses a 3-point Likert scale where respondents are provided with a series of statements and then asked to verify the frequency with which they agreed to the statement. For example, the first statement in the HFSSM is: “The food that (I/we) bought just didn’t last, and (I/we) didn’t have money to get more. How often was that true for you and your household in the last 12 months?” For this question, respondents were asked to answer with one of the following options: often true, sometimes true, or never true. For other questions, respondents were asked to answer with one of the following questions: almost every month, some months but not every month, and only 1 or 2 months. Responses of “often” or “sometimes” on the scale were coded as “affirmative” (yes) and allocated a point. Responses of “almost every month” and “some months but not every month” were also coded as affirmative (yes) and also allocated a point. The sum of affirmative responses to the six questions in the module is the household’s raw score on the scale.

Completed surveys were given scale scores and classified into food security levels based on standard values in total number of affirmatives, as outlined in previous research (Nord, 2011): 0–1 = high or marginal food security (low food insecurity), 2–4 = low food security (high food insecurity), and 5–6 = very low food security (very high food insecurity). The reliability and validity of the HFSSM has been well established in previous research where the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was between 0.808 and 0.818 (Nord, 2011).

Childhood hunger. The instrument used to measure childhood hunger was the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project (CCHIP) index (Wehler et al., 1996). The CCHIP hunger index was one of the first scales developed to measure hunger in families with at least one child under the age of 12 (Keenan et al., 2001). The scale is comprised of eight items that indicate whether adults or children in the household are affected by food insufficiency attributable to constrained resources. Four of these questions are related to children in the household; two questions are related to hunger of adult members of the household; and two questions are related to household food insufficiency (Kleinman et al., 1998).

For these questions, respondents were provided a statement, then asked to respond with their level of agreement on a four-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree. The first question in the CCHIP hunger index is: My child(ren) are not eating enough because I just can’t afford enough food. Responses that indicated agree or strongly agree were coded as affirmative; responses that indicated disagree or strongly disagree were coded as negative. Two of the survey items on the CCHIP are the same as two questions on the HFSSM. Each affirmative response is given a point on the scale. A score of 5 or more affirmative answers on the CHHIP indicates that the child(ren) are experiencing hunger. A score of 1 to 4 indicates that the family is at risk of hunger. If there are no affirmative responses to the questions, the child(ren) are not classified as risk for hunger.

Insurance status. Insurance status was initially measured using three categories: public insurance (i.e., MediCare, Medicaid, VA, other public health insurance); private and none. In the statistical analyses for the present study, insurance status was recoded as a dichotomous variable, indicating whether or not individuals had health insurance at all.

Depression symptoms. Depression symptoms were measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). The PHQ-9 is a version of the PRIME-MD diagnostic instrument for common mental disorders (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002). The PHQ-9 is the depression module of this measure, which has been widely validated in a variety of clinical settings, including primary care and outpatient mental health, with strong reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.86) (Kroenke et al., 2001). Minimal depression is indicated by scores in the 0–4 range; mild depression by scores in the 5–9 range; moderate depression by scores in the 10–14 range; moderately severe for scores in the 15–19 range; and severe in the 20–27 range.

Food pantry use. Frequency of food pantry use was quantified by the number of self-reported visits made by individual/family households since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. To ensure that we captured the intentions of first-time visitors to the food pantry, we also asked about anticipated food pantry use over the coming months (although this indicator was not used in final regression models).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were run for all sociodemographic variables and predictor variables of interest. Bivariate correlations were run between all variables and two outcomes of interest: (1) the HFSSM score and (2) the CCHIP hunger index. Because this was an exploratory study, variables that had previously been found to be associated with food insecurity or that indicated statistically significant correlations with food insecurity at the p < .05 level were included in multivariable linear regression models, predicting each independent outcome: food insecurity and childhood hunger. Stepwise linear regression models were used to create the final models, only including variables that resulted in a statistically significant change to the R-squared values for each step of the model. For food insecurity, the final regression model included the following variables: being female, Hispanic/Latinx, having one or more children, having health insurance, experiencing depression symptoms (measured by the PHQ-9 score), and frequency of food pantry use. For childhood hunger, the final regression model included: being female, Spanish being spoken at home, having a graduate degree, having health insurance, experiencing depression symptoms, and frequency of food pantry use. Missing data were handled with listwise deletion where any individual in the data set was deleted from analysis if there was any missing data for any variable in the analysis. All data were analyzed in SPSS v.26 (IBM Corp, 2019).

Dissemination of Findings

Following a CBPR approach, as we collected data and analyzed findings, the team continued to consult and collaborate with community members and nonprofit administrators to ensure that study findings were in accordance with community opinion. The research team had meetings with BronxWorks leadership and staff to ensure accurate dissemination of study findings, following the completion of surveys. These meetings also helped to identify the goals of the next phase of the project, which we decided was to gather additional qualitative information regarding the lived experiences of food insecurity in the Bronx. Through a CBPR method of need prioritization, we collectively decided that the next phase of the project would be to conduct in-depth interviews with food pantry recipients, key informant interviews with BronxWorks leadership, and focus groups with Bronx Works staff. This next stage of the research process helped ensure that our interpretation of survey results was accurate and in accordance with community perceptions.

Ethical Considerations

Study risks and benefits were orally explained to all participants, in either English or Spanish. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants prior to data collection in order to publish their survey responses in aggregated form, without any reference to personally identifiable information. Copies of the written informed consent form were made available to all participants. The study protocol was approved by the Fordham University Institutional Review Board and reviewed by the BronxWorks’ leadership team in July 2021.

Results

An initial sample of 230 was retrieved from the Qualtrics platform. After cleaning the dataset to remove duplicate, incomplete or ineligible responses, we had a final sample of 218 respondents. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics for the study sample.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

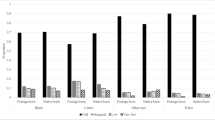

As depicted in Table 1, the sample mean for age was 55.85 years (13.13). Most participants identified as white (58.71%), female (82.56%), heterosexual (96.33%), Hispanic/Latinx (84.86%), Christian (89.90%), spoke English at home (80.27%), and were born in the Dominican Republic (65.14%). Household size was on average 3.92 members (SD = 1.70) and the majority of households (62.81%) had one or more children. The majority of households (80.72%) received an income of less than $30,000 annually. Only 9.17% were employed full-time and a significant proportion (37.61%) indicated having a disability. Of the sample, 37.15% reported having a high school degree or less. In terms of COVID-19 exposure, 27.52% reported being previously diagnosed with COVID-19 and 31.19% reported experiencing COVID-19 symptoms. The majority had been vaccinated for COVID-19 (84.9%). Most participants (72.5%) reported that they used the food pantry once a week. The mean score for depression symptoms, as measured by the PHQ-9, was 5.70 (5.29), indicating a mild degree of depression.

Food Insecurity

The HFSSM mean score was 3.43 (1.08), indicating high food insecurity. Income and household size were not significantly associated with food insecurity in bivariate models, likely because of lack of heterogeneity in our sample. Therefore, these variables were not included in final regression models. As shown in Table 2, in adjusted regression models, risk factors for food insecurity included: having one or more children (β = 0.153; p = .025) and experiencing depression symptoms (β = 0.232.; p < .001). Having insurance was a protective factor against food insecurity (β = − 0.283; p = .015). Gender, Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, and frequency of pantry use were not significantly associated with food insecurity in both adjusted and unadjusted models.

Childhood Hunger

The CCHIP mean score was 2.79 (1.71), indicating that the sample is generally at risk of hunger. Income and household size were again not significantly associated with childhood hunger in unadjusted models, so were not included in final regression models. As indicated in Table 3, protectors against childhood hunger were: Spanish being spoken at home (β = − 0.173; p = .043), having a graduate degree (β = − 0.180; p = .036) and having health insurance (β = − 0.283; p = .001). As with the food insecurity outcome, experiencing depression symptoms was positively associated with childhood hunger (β = 0.361; p < .001). Neither gender nor frequency of pantry use were significantly associated with childhood hunger in both adjusted and unadjusted models.

Discussion

The main findings from our study were that: (1) having one or more children increases risk for food insecurity for families receiving food pantry services in the Bronx; (2) having insurance was protective against food insecurity; (3) Spanish being spoken at home, having a graduate degree, and having health insurance were protective against childhood hunger; (4) experiencing depression symptoms was associated with increased risk for both food insecurity and childhood hunger; and (5) food pantry use was not significantly associated with either food insecurity or childhood hunger.

Our first two findings suggest that targeting families with multiple children and without insurance will best help to promote food security among residents of the south Bronx. Identifying priorities for community outreach in the Bronx will help ensure that the most vulnerable families receive necessary food assistance. In regard to the third finding, we noted protective factors against childhood hunger were: Spanish being spoken at home, having a graduate degree, and having health insurance. Lower levels of education have been found in previous research to be associated with increased food insecurity (De Araujo et al., 2018), suggesting that increased access to education for families in the south Bronx may have impacts of food security. Similar to previous findings (Berkowitz et al., 2018b), health insurance status appeared as a prominent predictor for both food insecurity and childhood hunger in our study. Spanish being spoken at home as a protective factor against childhood hunger is a novel finding and may be reflective of certain collectivist benefits of Latinx families. Previous research has demonstrated how bilingual or bicultural families experience other health protections, including improved children’s cognitive development, delay of cognitive decline, and delay of age of onset of dementia, namely Alzheimer’s Disease (Anderson et al., 2020; Bialystok et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings point to the greater need for wrap-around efforts at food pantries or perhaps neighborhood-level interventions that address access to health insurance more directly.

Our fourth study finding highlights the strong association between mental health and food insecurity. Previous research has documented the robust association between food insecurity and depression (Pourmotabbed et al., 2020), particularly for mothers of young children (Melchior et al., 2009). This may be explained by the fact that people experiencing depression are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed (Nord et al., 2014), so experiencing depression heightens their risk for food insecurity. Longitudinal analyses suggest that there are bidirectional relationships here, with depression predicting food insecurity and food insecurity also increasing the risk of depressive symptoms or diagnosis for Major Depressive Disorder (Maynard et al., 2018). Further longitudinal and qualitative research is needed to more fully understand the complex relationships between food insecurity, poverty and mental health. Given how few of the households we surveyed in this study were actually accessing mental health services, this points to an important unmet need in social services. Future social service efforts should seek to more closely align the receipt of food pantry services with referrals for mental health care. Food pantries have the potential to serve as effective entry points for linking clients to a range of social services, including mental health counseling, housing assistance, legal aid, job training and placement.

In regard to our fifth finding, food pantry use was not significantly associated with either food insecurity or childhood hunger in both adjusted and unadjusted models. These results suggest, that even with the receipt of regular food pantry services, many families in the Bronx remain food insecure and have children in threat of experiencing hunger. Our findings, coupled with previous research evaluating 60 food pantries in NYC, suggest that the emergency food system is ultimately unable to accommodate community needs (Gany et al., 20132013). Similar to our own findings, food pantry accessibility issues have included restricted service hours and documentation requirements (Gany et al., 2013). Food services were also limited in quantity of food provided and the number of nutritious, palatable options (Gany et al., 2013). To manage experiences of food insecurity, East Harlem residents carefully managed food spending, dedicated substantial time to visiting stores and accessing food pantries, and relied on a cycle of public benefits (i.e., cash assistance and SNAP) that left many without sufficient financial resources by the end of each month (Nieves et al., 2021). Food pantry services may be greatly improved through the coordination of public agencies to influence the food system and advocate for local policies, including neighborhood zoning and labor regulations, to improve food access (Cohen & Ilieva, 2021).

Limitations

Our findings are limited by our relatively small sample size and the cross-sectional nature of this survey data collection. Given that we only surveyed food pantry recipients at one site in the south Bronx, it is unlikely that these results can be extrapolated to all New York City residents. However, given that the focus of our project was to characterize the sociodemographics of food pantry recipients in an under-resourced community in NYC, we do not see this as limiting the importance of our conclusions regarding the food security of marginalized NYC residents. Additionally, to reduce potential participant discomfort, we did not ask participants to disclose their documentation status. As such, we may have missed valuable information regarding the intersectional vulnerabilities to food insecurity experienced by undocumented residents of the south Bronx.

Another study limitation is the way that we categorized race/ethnicity. We followed the U.S. Census guidelines that treat Hispanic/Latinx as an ethnicity, rather than a race. This categorized our sample as being 84.86% Hispanic/Latinx by ethnicity. However, by race, the sample was 58.71% White, 36.69% Black, 1.83% Asian and Pacific Islander and 0.45% American Indian/Alaska Native. Additionally, 65.14% of the sample identified as being born in the Dominican Republic. As González-Hermoso and Santos (2019) state, separating race from ethnicity in surveys risks an inaccurate picture of the Latinx community that may underestimate the number of Hispanic/Latinx respondents and may facilitate the evasion of a more accurate count of this population. To avoid these issues, social science researchers may consider to treat Hispanic/Latinx as a stand-alone racial category.

Social Work Implications

Policy Implications Regarding Food Insecurity

Our findings suggest that current levels of local investment in food resources are inadequate, underscoring the need for increased federal, state and local funding for food assistance, particularly for low-income communities most severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. While the food bank system is essential to addressing food insecurity in the US, it is only one part of a larger social safety net (Zack et al., 2021) to fight hunger. Although food banks in the US served an estimated 46 million people in 2015 (Bacon & Baker, 2017), these impacts remain insufficient to fully combat food insecurity in the United States. With rising inflation costs continuing to impact the cost of food nationally and within NYC, issues of food insecurity will not self-resolve without aggressive and sustained local government intervention. Although rates of COVID-19 incidence have waned in recent months, international prices for major food items, such as rice, wheat, maize, soybeans, vegetable oils, dairy and meat, have risen with inflation rates (Vos et al., 2022), making the food insecurity crisis far from over.

Scholars have argued that understandings of food security should encompass dynamics that affect hunger and malnutrition, namely agency and sustainability (Clapp et al., 2021). While this project addresses these individual-level factors, we are also aware of the substantial impact of social policy on food security. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has been fueled by the inadequacy of a social welfare infrastructure that counteracts the negative impacts of heightened unemployment, rising inflation costs, and the limited purchasing power of low-income families. Neighborhood residents who have better access to supermarkets and limited access to convenience stores tend to have healthier diets and lower levels of obesity (Larson et al., 2009). Understanding food access through a relational framing emphasizes the neighborhood effects of food apartheid (Alkon et al., 2013) and supermarket redlining (Cummins et al., 2007) that underlie the socioeconomic disparities driving food insecurity, rather than focusing on individualized diet and exercise behavior.

Other influencing factors impacting food insecurity in New York City include the impact of the child tax credit, the disruption of the supply chain over the past several years, and heightened food costs. The Office of the New York State Comptroller (2023) reported that recipients of the enhanced federal Child Tax Credit reported greater declines in food insecurity than non-recipients. The Office therefore recommends renewing the Federal Child Tax Credit Expansion as another initiative to make meaningful reductions in poverty and food insecurity.

Another key issue in addressing food insecurity in the Bronx is the lack of eligibility of for several residents to benefit from the SNAP, more commonly known as food stamps. For every meal that is provided through the Feeding America network of food banks, nine times that number of meals are provided through SNAP benefits (Leone, 2020). Research demonstrates that SNAP is one of the most important elements of the social safety net and is the second largest anti-poverty program for children in the US (Hoynes et al., 2017). Previous social policy decisions from the 1970 and 1980 s intended to restrict access to public assistance and were shaped by the racialized politics of deservingness (Dickinson, 2022). The subsequent reduction in SNAP benefits led to the emergence of a private food assistance network, comprised of food banks and food pantries (Cabili et al., 2013). The USDA provides federal assistance to food banks by providing commodities through the Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP), first established in 1983. Since March 2020 the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has expanded its caseload for food stamp recipients to include an additional 6.2 million more participants. Given this rise in need, the New York State Comptroller (2023) recently recommended further expansions to SNAP and the Woman, Infants and Children (WIC) program. Specifically, the Comptroller recommended that the federal government extend temporary benefits related to SNAP and WIC until inflation’s impact on food costs subsidies. Further, the office suggests that eligibility levels for SNAP and WIC should be increased to at least 200% of the federal poverty level.

Further, local social policies also have an impact on food insecurity in the Bronx. New York City food policy has slowly evolved from a focus on nutrition and diet to broader efforts aiming to increase social equity (Cohen & Ilieva, 2021). On April 15, 2020, then NYC Mayor de Blasio and the Food Czar team released the Feeding New York report, outlining a $25 million investment in the NYC’s food pantry system, the establishment of a $50 million emergency food reserve, and the creation of GetFood NYC (NYC Food Policy, 2021). GetFood NYC included the Department of Education Grab & Go Meal program, the Emergency Food Home-Delivered Meal program, and increased support and coordination for pantries and other emergency food distribution efforts. Between September 2020 and November 2021, which overlapped with our own data collection period, nearly 30 million pounds of fresh fruits and vegetables and over 10 million pounds of shelf-stable food were distributed to over 400 emergency food providers across the city (NYC Food Policy, 2021). Many of these city programs have also been canceled or downsized at this later stage in the pandemic.

Additionally, our study findings highlight the racialized mechanisms in which food insecurity differentially impacts residents of the south Bronx. The NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has examined food insecurity as part of its efforts to eliminate race-based health inequities through its Bureaus of Neighborhood Health program in East Harlem, Central Brooklyn, and the South Bronx—neighborhoods with high rates of chronic disease and premature mortality (Dannefer et al., 2020; Nieves et al., 2022). The approach adopted by the Bureaus emphasizes the importance of health equity and the social determinants of health (Srinivasan & Williams, 2014). Although promising and well-intentioned, our findings suggest that, even with a relatively robust suite of food assistance and social services that were available to residents of certain NYC neighborhoods, these services are not offered uniformly throughout the city, leaving vulnerable families in the south Bronx with inadequate food assistance. Our surveys were also collected during a time period in the pandemic when the most robust food assistance services were being offered in NYC and we can anticipate that with the removal/reduction of these added services, families in the Bronx will again be at increased risk for food insecurity and childhood hunger in coming months. Previous attempts to solve this issue have included proposals to initiate an emergency food assistance needs assessment, utilizing a rapid mapping approach that focuses on identifying areas of high food insecurity and assessing the population’s proximity to food pantry locations (Bacon & Baker, 2017). Such an approach may continue to prove to be useful in the current context.

Policy Implications Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic

Funding for TEFAP was increased through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act. Other important changes approved by the Families First Coronavirus Response Act included a suspension of the three-month time limit on low-income adults without children to receive food stamp benefits from SNAP and the creation of the Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer program, which enabled households with children who access free or reduced-price meals at school to receive extra benefits while students were learning remotely. However, similar to many of NYC’s emergency food programs, many of these programs have been discontinued or downsized as emergency funding streams during the pandemic for food assistance have ceased. In the State of New York, February 2023 was the last month that the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Emergency Allotment was issued; in March 2023, SNAP benefited returned to reduced, pre-pandemic amounts. Additionally, documentation status may prevent families from the Bronx from availing of SNAP and other federal entitlements, both before and after the pandemic.

Conclusion

Taken together, this study and the extant research strongly suggest that while food pantries are essential to addressing food insecurity, these programs are inadequate to effectively control both food insecurity and childhood hunger for NYC residents, and particularly for low income residents of the south Bronx without insurance and with children in their households. Targeting families with multiple children and without insurance may best help to promote food security among residents of the south Bronx. While food pantries offer assistance to families who may be ineligible for other federal or state benefits, these resources remain insufficient for overcoming food insecurity for some of the most marginalized communities in New York City.

References

Ahn, S., & Norwood, F. B. (2021). Measuring food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic of spring 2020. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 43(1), 162–168.

Alkon, A. H., Block, D., Moore, K., Gillis, C., DiNuccio, N., & Chavez, N. (2013). Foodways of the urban poor. Geoforum, 48, 126–135.

Althoff, R. R., Ametti, M., & Bertmann, F. (2016). The role of food insecurity in developmental psychopathology. Preventive Medicine, 92, 106–109.

Anderson, J. A., Hawrylewicz, K., & Grundy, J. G. (2020). Does bilingualism protect against dementia? A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27, 952–965.

Bacon, C. M., & Baker, G. A. (2017). The rise of food banks and the challenge of matching food assistance with potential need: Towards a spatially specific, rapid assessment approach. Agriculture and Human Values, 34(4), 899–919.

Berkowitz, S. A., Basu, S., Meigs, J. B., & Seligman, H. K. (2018a). Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011–2013. Health Services Research, 53, 1600–1620.

Berkowitz, S. A., Seligman, H. K., Meigs, J. B., & Basu, S. (2018b). Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: A longitudinal cohort study. The American journal of managed care, 24(9), 399.

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I., & Luk, G. (2012). Bilingualism: Consequences for mind and brain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(4), 240–250.

Blumberg, S. J., Bialostosky, K., Hamilton, W. L., & Briefel, R. R. (1999). The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. American Journal of Public Health, 89(8), 1231–1234.

Briefel, R. R., & Woteki, C. E. (1992). Development of food sufficiency questions for the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Journal of Nutrition Education, 24(1), 24S–28S.

Bufkin, A., & Kimiagar, B. (2020, July 2). More resources are needed to combat food insecurity in New York and across the country. Citizens’ Committee for Children of New York. https://www.cccnewyork.org/blog/more-resources-are-needed-to-combat-food-insecurity-in-new-york-and-across-the-country/

Cabili, C., Eslami, E., & Briefel, R. (2013). White Paper on the emergency food assistance program (TEFAP). Mathematica Policy Research.

Clapp, J., Moseley, W. G., Burlingame, B., & Termine, P. (2021). The case for a six-dimensional food security framework.Food Policy,102164.

Cohen, N., & Ilieva, R. T. (2021). Expanding the boundaries of food policy: The turn to equity in New York City. Food Policy, 103, 102012.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Gregory, C., & Singh, A. (2014). Household food security in the United States in 2013. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report- 173, September 2014, 1–41.

Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M., Gregory, C., & Singh, A. (2019). Household food security in the United States in 2018. USDA-ERS Economic Research Report- 270, September 2019, 1–47.

Cook, J. T., Frank, D. A., Levenson, S. M., Neault, N. B., Heeren, T. C., Black, M. M., & Chilton, M. (2006). Child food insecurity increases risks posed by household food insecurity to young children’s health. The Journal of Nutrition, 136(4), 1073–1076.

Cummins, S., Curtis, S., Diez-Roux, A. V., & Macintyre, S. (2007). Understanding and representing ‘place’ in health research: A relational approach. Social Science & Medicine, 65(9), 1825–1838.

De Araujo, M. L., de Deus Mendonça, R., Filho, L., J. D., & Lopes, A. C. S. (2018). Association between food insecurity and food intake. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 54, 54–59.

De Oliveira, K. H. D., De Almeida, G. M., Gubert, M. B., Moura, A. S., Spaniol, A. M., Hernandez, D. C., & Buccini, G. (2020). Household food insecurity and early childhood development: Systematic review and meta-analysis.Maternal & Child Nutrition, 16(3), e12967.

Dickinson, M. (2022). SNAP, campus food insecurity, and the politics of deservingness. Agriculture and Human Values, 39(2), 605–616.

Fang, D., Thomsen, M. R., & Nayga, R. M. (2021). The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Bmc Public Health, 21(1), 1–8.

Fitzpatrick, K. M., Harris, C., Drawve, G., & Willis, D. E. (2021). Assessing food insecurity among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 16(1), 1–18.

Gany, F., Bari, S., Crist, M., Moran, A., Rastogi, N., & Leng, J. (2013). Food insecurity: Limitations of emergency food resources for our patients. Journal of Urban Health, 90(3), 552–558.

González-Hermoso, J., & Santos, R. (2019). Separating race from ethnicity in surveys risks an inaccurate picture of the Latinx community. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/separating-race-ethnicity-surveys-risks-inaccurate-picture-latinx-community.

Gundersen, C., & Ziliak, J. P. (2015). Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1830–1839.

Gundersen, C., Strayer, M., Dewey, A., Hake, M., & Engelhard, E. (2021). Map the Meal Gap 2021: An Analysis of County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2019. Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2022-07/Map%20the%20Meal%20Gap%202022%20Report.pdf

Hetrick, R. L., Rodrigo, O. D., & Bocchini, C. E. (2020). Addressing pandemic-intensified food insecurity. Pediatrics, 146(4), 1–4.

Hoynes, H. W., Bronchetti, E., & Christensen, G. (2017). The Real Value of SNAP Benefits and Health Outcomes. University of Kentucky Center for Poverty Research Discussion Paper Series, 104. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/ukcpr_papers/104

Hu, B. (2022). Older renters of color have experienced high rates of housing insecurity during the pandemic. Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/blog/older-renters-color-have-experienced-high-rates-housing-insecurity-during-pandemic

IBM Corp. (2019). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202.

Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., Becker, A. B., Allen, A. J., Guzman, J. R., & Lichtenstein, R. (2017). Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. Community-based Participatory Research for Health: Advancing Social and Health Equity, 3, 32–35.

Jarrott, S. E., Cao, Q., Dabelko-Schoeny, H. I., & Kaiser, M. L. (2019). Developing intergenerational interventions to address food insecurity among pre-school children: A community-based participatory approach.Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition,1–17.

Keenan, D. P., Olson, C., Hersey, J. C., & Parmer, S. M. (2001). Measures of food insecurity/security. Journal of nutrition education, 33, S49–S58.

Kleinman, R. E., Murphy, J. M., Little, M., Pagano, M., Wehler, C. A., Regal, K., & Jellinek, M. S. (1998). Hunger in children in the United States: Potential behavioral and emotional correlates. Pediatrics, 101(1), e3–e3.

Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric annals, 32(9), 509–515.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Larson, N. I., Story, M. T., & Nelson, M. C. (2009). Neighborhood environments: Disparities in access to healthy foods in the US. American journal of preventive medicine, 36(1), 74–81.

Lee, J. S., & Frongillo, E. A. Jr. (2001). Nutritional and health consequences are associated with food insecurity among US elderly persons. The Journal of nutrition, 131(5), 1503–1509.

Leone, K. (2020, May 12). Feeding America statement on House Introduction of HEROES Act. https://www.feedingamerica.org/about-us/press-room/feeding-america-statement-house-introduction-heroes-act-1

Lewit, E. M., & Kerrebrock, N. (1997). Childhood hunger. The future of children, 7(1), 128–137.

Maynard, M., Andrade, L., Packull-McCormick, S., Perlman, C. M., Leos-Toro, C., & Kirkpatrick, S. I. (2018). Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(1424), 1–36.

Melchior, M., Caspi, A., Howard, L. M., Ambler, A. P., Bolton, H., Mountain, N., & Moffitt, T. E. (2009). Mental health context of food insecurity: A representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics, 124(4), e564–e572.

Morales, D. X., Morales, S. A., & Beltran, T. F. (2021). Racial/ethnic disparities in household food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationally representative study. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities, 8(5), 1300–1314.

Nam, Y., Huang, J., Heflin, C., & Sherraden, M. (2015). Racial and ethnic disparities in food insufficiency: Evidence from a statewide probability sample. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(2), 201–228.

Nieves, C., Dannefer, R., Zamula, A., Sacks, R., Gonzalez, D. B., & Zhao, F. (2021). Come with us for a week, for a month, and see how much food lasts for you:” a qualitative exploration of food insecurity in East Harlem. New York City: Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

Nord, M. (2011). Food security in the United States: Household Survey Tools. Food Security in the United States. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture.

Nord, M., Coleman-Jensen, A., & Gregory, C. (2014). Prevalence of US food insecurity is related to changes in unemployment, inflation, and the price of food. Research in Agricultural and Applied Sciences. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Report Number 167, June 2014, 1–36. https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/262213/

Olson, C. M. (1999). Nutrition and health outcomes associated with food insecurity and hunger. The journal of nutrition, 129(2), 521S–524S.

Pereira, M., & Oliveira, A. M. (2020). Poverty and food insecurity may increase as the threat of COVID-19 spreads. Public health nutrition, 23(17), 3236–3240.

Platkin, C., Kwan, A., Zarcadoolas, C., Dinh-Le, C., Hou, N., & Cather, A. (2020). Understanding local food environments, food policies, and food technology: a study of two NYC neighborhoods. NYC Food Policy. http://www.nycfoodpolicy.com/understandinglocalfoodenvironments.

Pourmotabbed, A., Moradi, S., Babaei, A., Ghavami, A., Mohammadi, H., Jalili, C., & Miraghajani, M. (2020). Food insecurity and mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public health nutrition, 23(10), 1778–1790.

Schulz, A. J., Zenk, S. N., Kannan, S., Israel, B. A., Koch, M. A., & Stokes, C. A. (2005). CBPR approaches to survey design and implementation. Methods community based Particip Res Heal San Fr JosseyBass, 107 – 27.

Seligman, H. K., & Berkowitz, S. A. (2019). Aligning programs and policies to support food security and public health goals in the United States. Annual review of public health, 40, 319–337.

Slopen, N., Fitzmaurice, G., Williams, D. R., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Poverty, food insecurity, and the behavior for childhood internalizing and externalizing disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(5), 444–452.

Srinivasan, S., & Williams, S. D. (2014). Transitioning from health disparities to a health equity research agenda: The time is now. Public Health Reports, 129(1_suppl2), 71–76.

Stuff, J. E., Casey, P. H., Szeto, K. L., Gossett, J. M., Robbins, J. M., Simpson, P. M., & Bogle, M. L. (2004). Household food insecurity is associated with adult health status. The Journal of nutrition, 134(9), 2330–2335.

Sullivan, S. R., Bell, K. A., Spears, A. P., Mitchell, E. L., & Goodman, M. (2021). No community left behind: A call for action during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Services, 72(1), 89–90.

Vos, R., Glauber, J., Hernández, M., & Laborde, D. (2022). COVID-19 and food inflation scares. In J. McDermott, & J. Swinnen (Eds.), COVID-19 and global food security: Two years later. International Food Policy Research Institute.

Walsemann, K. M., Ro, A., & Gee, G. C. (2017). Trends in food insecurity among California residents from 2001 to 2011: Inequities at the intersection of immigration status and ethnicity. Preventive medicine, 105, 142–148.

Wehler, C. A., Scott, R. I., & Anderson, J. J. (1996). Development and testing process of the Community Childhood Hunger Identification Project Scaled Hunger Measure and its application for a general population survey Conference on Food Security Measurement and Research; Papers and Proceedings, January 1994, Washington DC Technical Appendix A. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Consumer Service.

Wight, V., & Thampi, K. (2010). Who are America‘s poor children? Examining food insecurity among children in the United States. National Center for Children in Poverty, Columbia University.

Wolfson, J. A., & Leung, C. W. (2020a). Food insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in early effects for US adults. Nutrients, 12(6), 1648.

Wolfson, J. A., & Leung, C. W. (2020b). Food insecurity during COVID-19: An acute crisis with long-term health implications. American Journal of Public Health, 110(12), 1763–1765.

Zack, R. M., Weil, R., Babbin, M., Lynn, C. D., Velez, D. S., Travis, L., & Fiechtner, L. (2021). An overburdened charitable food system: Making the case for increased government support during the COVID-19 crisis. American Journal of Public Health, 111(5), 804–807.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2021). Food Security Status of U.S. Households in 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/#insecure

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2022). How Many People Lived in Food-insecure Households? https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) (2006). Policy brief: Food security, June 2006, Issue 2. http://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/faoitaly/documents/pdf/pdf_Food_Security_Cocept_Note.pdf

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UN FAO) (2020). https://www.fao.org/state-of-food-security-nutrition

Feeding America (2020). Food insecurity in the United States. http://map.feedingamerica.org/

United Hospital Fund (2021a). A year of resolve: United Hospital Fund Annual Report 2021. https://uhfnyc.org/media/filer_public/79/c5/79c5be63-5b1a-43a5-8070-af62ff5806b6/uhf_2021_annualreport.pdf

Office of the New York State Comptroller (2023, Mar.). New Yorkers in Need: Food Insecurity and Nutritional Assistance Programshttps://www.osc.state.ny.us/files/reports/pdf/new-yorkers-in-need-food-insecurity.pdf

New York City (NYC) Health (2021). Epi Data Brief: Food Insecurity and Access in New York City during the COVID-19 Pandemic, 2020–2021. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/databrief128.pdf

New York City (NYC) Food Policy (2021). Food Metrics Report. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/foodpolicy/reports-and-data/reports-data.page

Food Bank for New York City (2020). Fighting more than COVID-19: Unmasking the state of hunger in NYC during a pandemic. https://1giqgs400j4830k22r3m4wqg-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/Fighting-More-Than-Covid-19_Research-Report_Food-Bank-For-New-York-City_6.09.20_web.pdf

Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) (2015). Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) for Baccalaureate and Master’s Social Work Programs (2015). https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL-(1).pdf.aspx

City Harvest (2022). Hunger in NYC. https://www.cityharvest.org/food-insecurity

United Hospital Fund (2021b). Some 2.6 Million New Yorkers Face Hunger this Holiday Season. https://uhfnyc.org/news/article/some-26-million-new-yorkers-face-hunger/

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2012). Household Food Security Survey module: Six-item short form Economic Research Service, USDA. https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Azhar, S., Ross, A.M., Keller, E. et al. Predictors of Food Insecurity and Childhood Hunger in the Bronx During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00927-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00927-y