Abstract

Collective traumas have a notable impact on adolescent well-being. While some youth face increased risk for mental health problems (e.g., those with maltreatment histories), many demonstrate resilience following traumatic events. One contributing factor to well-being following trauma is the degree to which one isolates from others. Accordingly, we examined the association between maltreatment and internalizing problems during the COVID-19 pandemic as moderated by social isolation. Among adolescents reporting pre-pandemic emotional abuse, those experiencing less isolation reported the lowest levels of anxiety symptoms. Among adolescents reporting pre-pandemic physical abuse, those experiencing less isolation reported the greatest levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The findings highlight a public health-oriented approach to youth well-being during collective trauma that extends beyond mitigating disease transmission.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Collective traumas have been demonstrated to have a long-lasting and negative impact on mental health, including the onset of depression and anxiety. Certain individuals may be at greater risk for negative mental health problems following a traumatic event. This includes people with a history of childhood maltreatment (e.g., physical abuse, emotional abuse), as well those with pre-existing depressive and anxiety symptoms. Yet, there are likely additional factors that may exacerbate the link between childhood maltreatment and risk for depression and anxiety. This includes public health practices aimed at mitigating the spread of disease during health-related disasters, such as social isolation. Although these practices may protect individuals from contracting an illness, it is possible that they inadvertently strengthen the link between pre-existing vulnerabilities and depression and anxiety. This study examines the role of social isolation as a potential moderator in the link between childhood maltreatment and subsequent internalizing problems during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devasting impact on the livelihood and mental health of people worldwide. Although public health policies focused on mitigating the spread and severity of infection (e.g., vaccinations, quarantine) have been highly effective, the psychological impact of COVID-19 is likely to persist for years to come. Adolescents, who are more susceptible to psychological and social changes compared to other age groups, were found to experience high levels of mental health impairment largely due to drastic changes in their social lives given transitions to remote learning and social distancing (Shah, Mann, Singh, Bangar, & Kulkarni, 2020). While the COVID-19 pandemic is unique, there is much to be gleaned from this collective trauma to support adolescents in response to future collective traumas that are increasing in frequency, including natural disasters which have evidenced a fivefold increase in the last 50 years (World Meteoreological Organization (2021)) and mass shootings with reports of over 600 in 2022 alone (Ledur & Rabinowitz, 2022).

Collective traumas, including the COVID-19 pandemic, are outcomes of events that are traumatic for both individuals and society (Eriksson, 2018) necessitating collective self-reflection (Eriksson, 2016), creating a shared memory of the event(s), and challenging our beliefs about safety, control, and the human experience (Hirschberger, 2018). Collective traumas also contribute to the emergence of psychological disorders among adolescents, such as generalized anxiety and major depression (Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020). Indeed, significant associations between COVID-19 and psychological well-being among children and adolescents has been empirically supported (Chawla et al., (2021)). Although adolescence represents a critical period wherein a significant portion of youth develop social-emotional mental health problems, certain adolescents may be at an especially greater risk following traumatic events. For example, a large literature indicates that pre-existing anxiety and depressive symptoms among adolescents increase subsequent risk for a more severe and persistent course of mental health problems following a traumatic event (Iob, Frank, Steptoe, & Fancourt, 2020). Research also supports a connection between experiences of childhood maltreatment (e.g., sexual, physical, and emotional abuse) and mental health outcomes across the lifespan (e.g., Janiri et al., 2021). Less is known about the role of childhood maltreatment in an adolescent’s response to collective trauma, compared to prior work demonstrating that childhood maltreatment contributes to worse outcomes following a collective traumatic event in adulthood (Garfin, Holman, & Silver, 2020). This represents a critical gap in the literature as over 1 billion children (ages 2 to 17) globally experience sexual, physical, or emotional abuse each year (Hillis et al., 2016). Given the high prevalence of childhood maltreatment and increased vulnerability to mental health problems during adolescence, it is of utmost importance to examine the impact of collective traumas, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on anxiety and depression among adolescents with maltreatment histories.

There is a large literature supporting the link between child maltreatment and risk for depression and anxiety (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011; Janiri et al., 2021). Prior work on “sensitization effects” indicate that exposure to childhood maltreatment increases vulnerability to later stressful events, including collective traumas (McLaughlin, Conron, Koenen, & Gilman, 2010). More recently, work has examined how the impact of COVID-19 on anxiety and depression may be exacerbated among people reporting experiences of childhood maltreatment (Iob et al., 2020; Janiri et al., 2021; Usher, Bhullar, Durkin, Gyamfi, & Jackson, 2020). Yet, this work has focused primarily on adults via retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment, which has notable methodological limitations (Iob et al., 2020; Janiri et al., 2021). When youth have been the focus of prior work examining childhood maltreatment as a predictor of depression and anxiety during adolescence, there tends to be a narrow consideration of youth in either the foster care or juvenile justice systems (Moretti & Craig, 2013; Salazar, Keller, & Courtney, 2011). Although this information is valuable, results may not generalize to community samples given the unique and challenging experiences precipitating and comprising one’s involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Thus, a focus on the role of maltreatment on depression and anxiety during a collective trauma among a community sample of adolescents could provide novel knowledge to help inform public health policies and interventions more broadly.

Childhood and adolescence represent critical developmental periods with respect to emotional regulation and social skills development (Schweizer, Gotlib, & Blakemore, 2020). Life experiences, such as maltreatment (especially emotional abuse), can have a notable impact on a youth’s ability to acquire these skills early in development contributing to maladaptive functioning later in life (Alink et al., (2009)). Deficits in regulating emotions and problems interacting with others can contribute to severe difficulties coping with new stressors and forming positive relationships with others (Powers, Ressler, & Bradley, 2009). Some posit that the constant sensitization of the central nervous system, integral in the effective regulation of emotions and stress, during notable periods of maturation (i.e., childhood and adolescence) among those experiencing maltreatment represent biological substrates that increase vulnerability to mental health problems following subsequent traumatic events (Martins-Monteverde et al., 2019). In fact, prior work indicates that the association between maltreatment and mental health problems was larger in child and adolescent samples compared to adult samples, which supports childhood and adolescence as a critical period in development (Humphreys et al., 2020).

Previous studies examining the impact of childhood maltreatment on depression and anxiety have largely focused on physical abuse (Christ et al., 2019; Courtney, Kushwaha, & Johnson, 2008). Yet, the rates of children worldwide who have experienced emotional abuse (~36%) is greater than the rates of physical abuse (~22%; World Health Organization, 2014). There is also significant overlap and intercorrelation among types of childhood maltreatment within community-based samples (Christ et al., 2019). Accordingly, associations between physical abuse and mental health outcomes may be overestimated or distorted by the impact of other types of abuse. When examined in the same model, prior work demonstrates that emotional abuse has a more deleterious impact on functioning and mental health outcomes compared to physical abuse (Courtney et al., 2008; Martins, Baes, de Carvalho Tofoli, & Juruena, 2014; Powers et al., 2009). Importantly, some estimate that the risk of developing a depressive disorder across the lifespan is almost double among people who have experienced childhood emotional abuse compared to people who have experienced childhood physical abuse (Norman et al., 2012). Given the relative dearth of studies focused on childhood emotional abuse, combined with the high prevalence and evidence supporting childhood emotional abuse as the most severe form of maltreatment, the current study examines the unique role of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse on adolescent anxiety and depression during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite these known negative outcomes and high rates of maltreatment, not all individuals who experience childhood maltreatment go on to experience mental health problems, even when exposed to subsequent stressors or collective traumas. Understanding factors that may exacerbate the effects of childhood maltreatment during a collective trauma could inform public health policies and interventions to promote well-being among those most vulnerable. One factor that has received increased attention is social isolation (Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020). In his foundational sociological study of stress, Pearlin (1989) posits the importance of not only examining direct causes of stress following specific traumatic events, but also indirect effects that traumatic events may have on life conditions, including social isolation. In fact, consequences of negative life events, such as social isolation, are viewed as stronger predictors of later mental health problems than the precipitating events that created these circumstances (Pearlin, 1989). For example, one study found that post-traumatic stress scores were four times higher in children who had experienced significant periods of social isolation than those not isolating from others during health-related disasters (Sprang & Silman, 2013).

Although belongingness and social connections are viewed as intrinsic human needs across the lifespan (Matthews et al., 2015), the impact of social isolation is perhaps most salient during the adolescent developmental period. Adolescence is characterized by increased time spent with peers, heightened sensitivity to social reward, and engagement in experiences that emphasize socialization (Trucco, 2020). Aligning with this perspective, one study found that disease-containment measures, such as social isolation, during a health-related disaster resulted in 30% of youth meeting the clinical cutoff score for post-traumatic stress disorder compared to only 25% of parents (Sprang & Silman, 2013). Similarly, younger age (16–24 years) was associated with greater negative psychological impacts among individuals who socially isolated following a health-related outbreak (Taylor, Agho, Stevens, & Raphael, 2008). Yet, the risks conferred on adolescents due to mandated social isolation procedures over a more sustained period of time is not as well-understood.

Health pandemics, including the COVID-19 pandemic, are unique collective traumas in that social isolation measures are often implemented (Benke, Autenrieth, Asselmann, & Pane-Farre, 2020). Although these practices are important to help mitigate the spread of the disease, they likely have a negative impact on the mental health and well-being of adolescents in both the short- and long-term (Galea, Merchant, & Lurie, 2020; Riiser, Helseth, Haraldstad, Torbjornsen, & Richardsen, 2020). For example, recent work indicates that periods of isolation, even less than 10 days, can impact mental health symptoms up to three years later (Brooks et al., 2020). School closures during the COVID-19 pandemic affected over 1.5 billion children, which curtailed a significant degree of social connections for most adolescents (Bhatia et al., 2020). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic cultivated the belief that social isolation likely offered the best protection amidst conflicting and rapidly evolving recommendations on the use of masks and congregating with others indoors (Pietrabissa & Simpson, 2020). Thus, maintaining meaningful social connections with others during health pandemics represents a challenge. Yet, it remains unclear whether this challenge has a disproportionate impact on anxiety and depression among adolescents with a history of childhood maltreatment. A greater understanding regarding the impact of social isolation on the association between childhood maltreatment and adolescent mental health could inform personalized interventions and direct resources towards youth most vulnerable to collective traumas.

Current Study

Adolescence is a notable developmental period that is characterized by greater risk for the onset of social-emotional mental health problems, including depression and anxiety, compared to other developmental periods. Moreover, traumatic events experienced during adolescence enhance risk for the development of psychopathology and maladaptive functioning later in life. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is unique in many ways, it provides a window into the potential impact of collective traumas more broadly and potential protective and risk factors among those most vulnerable to life stressors (i.e., youth with maltreatment histories). The current study examines the role of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse on the development of depression and anxiety in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic and how social isolation may exacerbate this association. It is hypothesized that youth with maltreatment histories will report more depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic and that this association will be stronger among youth who experience greater social isolation. Strengths of the current study include a community sample of youth, the inclusion of pre-pandemic measures of childhood maltreatment, anxiety and depressive symptoms, and the examination of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent mental health.

Methods

Design and Sample

The current sample was comprised of a sub-sample of adolescents (N = 115; Mage = 14.9; 54.8% female; 86.0% White, 7.8% Black, <1% Pacific Islander, 5.2% Other racial category; 82.6% Latinx) enrolled in an online supplemental study focused on the impact of COVID-19 experiences among adolescents. The larger parent study (N = 276; 49.2% female; 85.5% White, 8.7% Black, 0.7% Pacific Islander, 5.1% Other racial category; 84.8% Latinx) is a multi-wave investigation of e-cigarette initiation. Eligibility criteria for the parent study included: being in the first or second year of high school, no diagnosis of a learning, intellectual, or physical disability, no diagnosis of a neurological disorder or disorder characterized by psychotic or paranoid symptoms, and English proficiency. Furthermore, given the parent study’s primary objective, adolescents had to endorse at least one of the following risk factors (e.g., elevated sensation seeking and/or impulsivity; see Trucco, Cristello, & Sutherland, 2021 for additional information). All participants in the parent study were eligible and invited to participate in this online supplemental study. The reasons provided from participants who chose not to participate in the online supplemental study included not having enough time to participate, being too busy with school/work, being ill or having to take care of an ill family member. Participants in the parent project versus the COVID sub-study did not significantly differ with respect to endorsement of physical abuse, (χ2 [1, N = 276] = 1.60, p = 0.21), emotional abuse (χ2 [1, N = 276] = 1.67, p = 0.20), sexual abuse (χ2 [1, N = 276]= 0.56, p = 0.45), biological sex (χ2 [1, N = 276] = 1.34, p = 0.25), or race (χ2 [1, N = 276] = 9.52, p = 0.05).

Procedures

Adolescents interested in participating provided contact information for their caregivers during school recruitment events. Caregivers were then contacted and provided with information regarding the study. For the current study, only Wave 1 data (W1; during summer 2018 to spring 2019) of the parent project were considered. All participants who were eligible for the parent study were invited to participate via email in the multi-wave online COVID-19 supplemental study, which involved completing questionnaires about COVID-19 experiences and mental health. For adolescent data in the current study, only sub-study measures collected during the following time periods were examined: Time 1 (T1; summer 2020) and Time 2 (T2; fall 2020). Consent and assent forms, as well as questionnaires were accessible to participants via REDCap (Harris et al., 2019) and took approximately 1 hour to complete. Participants were compensated $40 at W1, $15 at T1, and $20 at T2 for questionnaire completion.

Measures

Child Maltreatment (W1)

Adolescents self-reported pre-pandemic emotional, physical, and sexual abuse using items from the Child and Adolescent Trauma Screen (CATS; Sachser et al., 2017) and the Revised ACE Questionnaire (Finkelhor et al., 2015). More specifically, emotional abuse was assessed using four items (e.g., “Having a parent or other adult swear at you, insult you, put you down, or humiliate you often or very often”, “Having a parent or other adult act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt,” “Feeling that no one in your family loved you or thought you were important or special often or very often,” and “Feeling that your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other”; α = 0.77). Physical abuse was assessed using two items (“Slapped, punched, or beat up by someone in your family” and “Seeing someone in your family get slapped, punched or beat up”; r = 0.41, p = <0.001). Sexual abuse was assessed using two items (“Someone older touching your private parts when they shouldn’t” and “Someone forcing or pressing sex, or when you couldn’t say no.”; r = 0.49, p = <0.001). All items were answered with a dichotomous yes/no endorsement. Overall, 39.2% of the sample reported experiencing some kind of abuse. Frequencies across types and combinations of abuse were as follows: emotional abuse only (20.0%), physical abuse only (3.5%), sexual abuse only (0%), emotional and physical abuse (12.2%), emotional and sexual abuse (0%), physical and sexual abuse (0.9%), and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse (2.6%).

COVID-19 Social Isolation (T1)

Adolescents reported on social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic using a sum score of five items (e.g., “stay away from people [other than those who live in my house]”, “avoided visiting friends/family outside of own immediate family,” “avoided having people in our home, except for immediate family”; and two reverse-coded items, “not engaged in social distancing” and “still meeting up with friends”; α = 0.61). All items were answered with a dichotomous yes/no endorsement.

Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms (T2)

Adolescents reported mental health outcomes using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The current study focused on depressive symptoms (e.g., “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to”; α = 0.91) and anxiety symptoms (“I worried about situations in which I might panic and make a fool of myself”; α = 0.81). Both subscales were comprised of seven items and each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale (never to almost always).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS computer program (2013). Moderation models were conducted using ordinary least squares regression with bootstrapping (5000 resamples with replacement) using the PROCESS macro version 3.3 for SAS (Hayes, 2018). Covariates included race, age at W1, biological sex, and pre-pandemic (W1) anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed subscales from the Youth Self Report (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), respectively. Separate models were tested for anxiety and depressive symptoms and emotional and physical abuse, resulting in a total of four estimated models. Separate models were not estimated for sexual abuse given the low base rate in this sample. Significant interactions were probed using recommended guidelines by assessing values of social isolation corresponding to the mean (i.e., moderate) and one standard deviation above (i.e., high) and below (i.e., low) the mean (Cohen & Cohen, 1983).

Results

Means, standard deviations, and correlations for all study variables are presented in Table 1. Of particular interest, emotional abuse was associated with anxiety symptoms at W1 (r = 0.48, p < 0.001) and physical abuse was associated with anxiety symptoms at W1 (r = 0.25, p < 0.01) and W2 (r = 0.20, p < 0.05).

Emotional Abuse Models

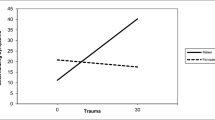

The first model examining emotional abuse and social isolation accounted for approximately 24% of the variance in anxiety symptoms. The first-order effects of biological sex and pre-pandemic anxiety symptoms were statistically significant, as was the two-way interaction (emotional abuse x social isolation; estimate=0.31, p < 0.05, 95% CI [0.00, 0.61]; Table 2). Moreover, the variance explained by the interaction was significant (ΔR2 = 0.03, p < 0.05). The simple slope of emotional abuse was marginal at low levels (t[107]=−1.65, p < 0.10), but not significant at moderate (t[107]=0.03, p = 97) or high levels (t[107]=1.53, p = 0.13) of social isolation. Thus, emotional abuse was negatively associated with anxiety symptoms among those reporting low levels of social isolation (see Fig. 1). Framed differently, youth reporting low emotional abuse endorsed high levels of anxiety symptoms in the context of low levels of social isolation; yet youth reporting high emotional abuse endorsed low levels of anxiety symptoms in the context of low levels of social isolation. The second model examining emotional abuse and social isolation accounted for approximately 16% of the variance in depressive symptoms. Only the first-order effects of biological sex and pre-pandemic depressive symptoms were statistically significant (see Table 2).

Physical Abuse Models

The third model examining physical abuse and social isolation accounted for approximately 26% of the variance in anxiety symptoms. The first-order effects of biological sex and pre-pandemic anxiety symptoms were statistically significant, as was the two-way interaction (physical abuse x social isolation; estimate = −0.77, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−1.43, −0.11]; Table 3). Moreover, the variance explained by the interaction was significant (ΔR2 = 0.04, p < 0.05). The simple slope of physical abuse was significant at low levels (t[107]=2.72, p < 0.01), marginal at moderate levels (t[107]=1.72, p < 0.10), but not significant at high levels (t[107]=−0.78, p = 0.44) of social isolation. More specifically, adolescents reporting low levels of physical abuse reported similar anxiety symptom severity across levels of social isolation. Yet, youth reporting high physical abuse endorsed high levels of anxiety symptoms in the context of low levels of social isolation and moderate levels of anxiety symptoms in the context of moderate levels of social isolation Fig. 2.

The fourth model examining physical abuse and social isolation accounted for approximately 20% of the variance in depressive symptoms. The first-order effects of biological sex, pre-pandemic depressive symptoms, and physical abuse were statistically significant, as was the two-way interaction (physical abuse x social isolation; estimate = −0.99, p < 0.05, 95% CI [−1.91, −0.07]; Table 3). The simple slope was significant at low social isolation (t[107]= 2.40, p < 0.05), but not significant at moderate (t[107]=1.28, p = 0.20) or high (t[107]= −1.05, p = 0.35) levels of social isolation. More specifically, adolescents reporting low levels of physical abuse reported similar depressive symptom severity across levels of social isolation. Yet, youth reporting high physical abuse endorsed high levels of depressive symptoms in the context of low levels of social isolation (Fig. 3).

Discussion

To develop the most effective interventions, it is important to understand who is most at-risk for negative long-term outcomes in the wake of collective traumas and identify possible factors that could exacerbate psychological distress during challenging times. Adolescence represents a developmental period that is characterized by the emergence of social-emotional mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression (Rapee et al., 2019). Compounding this risk are negative experiences, such as childhood maltreatment. Prior work indicates that adolescents who have a history of maltreatment are more likely to develop psychological disorders and experience impairment later in life, especially following subsequent traumatic events (Martins et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, certain experiences during collective traumas may exacerbate this already heightened predisposition for negative outcomes. Prior work indicates that social isolation, even less than 10 days, can have a deleterious impact on anxiety and depression up to three years later (Brooks et al., 2020). Events that significantly stifle opportunities for human connection may be especially damaging to adolescents given that this is a developmental period characterized by heightened social reward (Foulkes & Blakemore, 2016; Trucco, 2020). As it is not always possible to prevent childhood maltreatment, work that focuses on potential intervention targets to increase one’s capacity to effectively process challenging experiences (e.g., collective traumas) could have significant utility in impacting the well-being of those who are most vulnerable. The current study demonstrated that social isolation moderated the effect of maltreatment on mental health outcomes during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet, interesting nuances emerged across type of abuse, as well as across mental health problems, which could inform more targeted intervention strategies for youth.

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse not only represents the most prevalent form of maltreatment compared to physical and sexual abuse (Christ et al., 2019), it also represents the most severe form of abuse impacting a wider range of impairment across areas of functioning and having a greater negative impact on mental health disorders (Martins et al., 2014; Nöthling, Suliman, Martin, Simmons, & Seedat, 2019). Yet, emotional abuse is relatively understudied and has received less attention with respect to public health prevention and intervention (Cohrdes & Mauz, 2020). To redress this pattern in maltreatment research and utilize a globally relevant example of a collective trauma (i.e., COVID-19), we investigated the impact of social isolation on the association of maltreatment and mental health outcomes among adolescents. Accordingly, the current study found support for a statistically significant interaction between pre-pandemic emotional abuse and social isolation during the pandemic on adolescent anxiety symptoms. Consistent with prior work and hypothesized associations, emotional abuse predicted lower anxiety symptoms when controlling for pre-pandemic internalizing problems, but only among those reporting low levels of social isolation. This means that even when youth in our sample had experienced emotional abuse, if they experienced low levels of social isolation, they reported low levels of anxiety symptoms compared to those who socially isolated from others. Prior work focused on the impact of health pandemics on mental health outcomes indicates that separation from loved ones and loss of direct social contact with others due to social isolation mandates contributes to high levels of anxiety in the general population (Dagnino, Anguita, Escobar, & Cifuentes, 2020). The fact that social distancing practices have been demonstrated to be particularly detrimental to the mental health and well-being of high school and college students (Huang & Zhao, 2020; Shah et al., 2020) makes sense given the increased salience of socialization factors on adolescent functioning (Trucco, 2020). Moreover, prior work indicates that the COVID-19 pandemic and virus mitigation measures, such as social isolation, likely have a disproportionate negative impact on the mental health of adolescents in abusive households who already experience feelings of isolation (Gayer-Anderson et al., 2020). Yet, researchers have not examined the synergistic effect of emotional abuse and social isolation on internalizing symptoms among adolescents during a collective trauma event. Findings from the current project indicate that youth experiencing pre-pandemic emotional abuse are particularly vulnerable to the negative impact of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic resulting in high levels of anxiety, even when controlling for pre-pandemic anxiety symptoms.

Counter to our hypothesis, we did not find a similar pattern of results for models considering emotional abuse, social isolation, and depressive symptoms. Although prior work has supported an association between emotional abuse and depression (Christ et al., 2019; Courtney et al., 2008; Humphreys et al., 2020), there is also empirical support for a non-significant association between these constructs (Schulz et al., 2017). It is important to note that most of this prior work has not focused on mental health symptoms experienced in the context of a collective trauma event or considered the degree to which adolescents were socially isolated, which could account for some of these differences.

Physical Abuse

In contrast to findings from the emotional abuse models, an interactive effect between physical abuse and social isolation was found for both anxiety and depression in the current study. Moreover, the pattern of these findings was counter to our hypothesis. That is, physical abuse predicted greater anxiety and depressive symptoms when controlling for pre-pandemic internalizing problems, but only among those reporting low levels of social isolation. This finding suggests that high levels of social isolation did not serve as an additional vulnerability factor for internalizing symptoms among those with histories of physical abuse as expected. Although these findings are unexpected, the biological embedding hypothesis has utility in framing the current study findings. Namely, it posits that the association between childhood physical abuse and mental health may be driven by “scarring” that serves to impair one’s ability to effectively reap the benefits from social interactions with others, a fundamental human drive, which then contributes to the development of internalizing symptoms (Sheikh, 2018). Furthermore, the stress buffering model suggests that social isolation may attenuate the psychological impact of childhood physical abuse on internalizing symptoms by mitigating the stress appraisal response (Pearlin, 1989). That is, adolescents with physical abuse histories may have difficulties interpreting the thoughts and feelings of others and be more sensitive to perceived threats or signs of rejection from others (Sheikh, 2018), thus making social interactions stressful and exacerbating mental health problems for adolescents with pre-pandemic physical abuse histories. In addition, less social isolation may be synonymous with more time spent with others and youth who are living in the context of physical abuse may be worried that other people will detect this (e.g., notice bruises, observe changes in their mood). Many youth who experience abuse (regardless of type) do not ever disclose their abuse (Bottoms et al., 2016) and youth experiencing physical abuse may be more reluctant to disclose their abuse (compared to sexual abuse, for example) because it is often a parent figure inflicting the physical abuse (Hershkowitz, Horowitz, & Lamb, 2005). Thus, the worry or fear around someone finding out could also contribute to heightened anxiety and depression for youth experiencing physical abuse and not socially isolating from others. Another possibility is any amount of social isolation measures increased the amount of time adolescents had to spend in close proximity to the people who perpetrated the physical abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., caregivers living in the home), thereby intensifying the link between physical abuse and subsequent anxiety and depressive symptoms observed herein. Prior work indicates that violence against children and adolescents in the home significantly increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (Bhatia et al., 2020). Thus, future work examining the nature and quality, as well as perceived social isolation is critical.

While this study redresses a critical gap in the knowledge related to psychological well-being during a collective trauma among adolescents who have experienced maltreatment, there are some limitations. Related to measurement, our measure of childhood maltreatment flattens the multidimensional and complex experiences of maltreatment by not accounting for factors like duration or perpetrator identity. Furthermore, our measure of physical abuse included direct and indirect experiences of physical violence in the family. Different types of maltreatment and violence co-occur at high rates (Appel & Holden, 1998; Carlson et al., 2020; Chan, Chen, & Chen, 2021; Hamby et al., 2010; Liel et al., 2020) and both direct and indirect violence are associated with psychiatric problems, such as depression (e.g., Norman et al., 2012). Future research efforts should account for the multidimensional aspects of maltreatment and implement more rigorous evaluations of these experiences. Lastly, the sample was largely comprised of Latinx adolescents. The current study should be replicated with a more diverse sample. Nonetheless, this is one of the only studies to consider the impact of emotional and physical abuse on adolescent psychological well-being in the context of a collective trauma, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

Overall, there is a dearth of empirical studies that have considered the impact of social isolation on especially vulnerable populations in the context of pandemics and other public health crises. Our findings support prior work indicating that adolescents with emotional and physical abuse histories may be disproportionately impacted by social restrictions that confine people to their homes for extended periods of time. Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of a public health-oriented approach to adolescent well-being during times of collective trauma that extends beyond mitigating the spread of disease. Namely, restricting the length of quarantine based on what is known scientifically with respect to incubation periods, as opposed to implementing an overly precautionary lockdown approach on entire cities, may limit the negative impact of social isolation on the health and well-being of adolescents. In addition, identifying various levels of care (e.g., primary healthcare, school systems, and community and church organizations) to expand points of contact and connection for families could have significant utility during times of crisis. These settings could provide brief, cost-effective screenings for adolescents who demonstrate heightened risk for mental health problems following traumatic events, including those with maltreatment histories. Findings also highlight the role of social isolation as either a protective or risk factor based on the specific type of abuse experienced in the context of a collective trauma. While certain health policies may be critical in mitigating the spread of disease (e.g., quarantine, social distancing), maintaining supportive social connections for youth is critical. Not only can digital technologies (e.g., video chats) bridge social distance even while quarantine measures are in place, they may also help maintain formal and informal support structures through the community and school. Accordingly, ensuring that internet access is maintained to help uphold social connections, prevent disruption in schoolwork, and access supports is critical. In light of evidence showing disproportionate mental health effects on adolescents with pre-pandemic abuse histories, policies should prioritize providing personalized public health messaging and ensuring adequate service capacity to meet the specific needs of groups that are at greater risk for mental health problems in the face of collective trauma events.

Data Sharing and Declaration

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not yet publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth & Families.

Alink, L. R., Cicchetti, D., Kim, J., & Rogosch, F. A. (2009). Mediating and moderating processes in the relation between maltreatment and psychopathology: Mother-child relationship quality and emotion regulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(6), 831–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9314-4.

Appel, A. E., & Holden, G. W. (1998). The co-occurrence of spouse and physical child abuse: A review and appraisal. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(4), 578–599. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.4.578.

Benke, C., Autenrieth, L. K., Asselmann, E., & Pane-Farre, C. A. (2020). Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: Associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462.

Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x.

Bhatia, A., Fabbri, C., Cerna-Turoff, I., Tanton, C., Knight, L., Turner, E., & Devries, K. (2020). COVID-19 response measures and violence against children. Bulletin World Health Organization, 98(9), 583–583A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.20.263467.

Bottoms, B. L., Peter-Hagene, L. C., Epstein, M. A., Wiley, T. R. A., Reynolds, C. E., & Rudnicki, A. G. (2016). Abuse characteristics and individual differences related to disclosing childhood sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and witnessed domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 1308–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514564155.

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395, 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

Carlson, C., Namy, S., Norcini Pala, A., & Devries, K. (2020). Violence against children and intimate partner violence against women: Overlap and common contributing factors among caregiver-adolescent dyads. BMC Public Health, 20, 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8115-0we.

Chan, K. L., Chen, Q., & Chen, M. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of the co-occurrence of family violence: A meta-analysis on family polyvictimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019841601.

Chawla, N., Tom, A., Sen, M. S., & Sagar, R. (2021). Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on children and adolescents: A Systematic review. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 43(4), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/02537176211021789.

Christ, C., de Waal, M. M., Dekker, J. J., van Kujik, I., van Schaik, D. J. F., Kikkert, M. J., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2019). Linking childhood emotional abuse and depressive symptoms: The role of emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems. PLOS One, 14(2), e0211882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211882.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohrdes, C., & Mauz, E. (2020). Self-efficacy and emotional stability buffer negative effects of adverse childhood experiences on young adult health-related quality of life. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67, 93–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.005.

Courtney, E. A., Kushwaha, M., & Johnson, J. G. (2008). Childhood emotional abuse and risk for hopelessness and depressive symptoms during adolescence. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 8(3), 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926790802262572.

Dagnino, P., Anguita, V., Escobar, K., & Cifuentes, S. (2020). Psychological effects of social isolation due to quarantine in Chile: An exploratory study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.591142.

Eriksson, M. (2016). Managing collective trauma on social media: The role of Twitter after the 2011 Norway attacks. Media, Culture & Society, 38(3), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443715608259.

Eriksson, M. (2018). PIzza, beer and kittens: Negotiating cultural trauma discourses on Twitter in the wake of the 2017 Stockholm attach. New Media & Society, 20(11), 3980–3996. https://doi.org/10.1177/146144481765484.

Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2015). A revised inventory of adverse childhood experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.011.

Foulkes, L., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2016). Is there heightened sensitivity to social reward in adolescence. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 40, 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2016.06.016.

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562.

Garfin, D. R., Holman, E. A., & Silver, R. C. (2020). Exposure to prior negative life events and responses to the Boston marathon bombings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(3), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000486.

Gayer-Anderson, C., Latham, R., El Zerbi, C. V., Strang, L., Moxham Hall, V., Knowles, G.,… & Rose, D. (2020). Impacts of social isolation among disadvantaged and vulnerable groups during public health crises. ESRC, Centre for Society and Mental Health, Kings College London. Available at: https://www.careknowledge.com/media/47410/3563-social-isolation-2-cs-v3.pdf (accessed 26 March 2023).

Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., & Ormrod, R. (2010). The overlap of witnessing partner violence with child maltreatment and other victimizations in a nationally representative survey of youth. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(10), 734–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.03.001.

Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Minor, B. L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., & Consortium, R. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Information, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to Mediation. Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hershkowitz, I., Horowitz, D., & Lamb, M. E. (2005). Trends in children’s disclosure of abuse in Israel: A national study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 1203–1214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.04.008.

Hillis, S., Mercy, J., Amobi, A., & Kress, H. (2016). Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154079. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4079.

Hirschberger, G. (2018). Collective trauma and the social construction of meaning. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1441. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01441.

Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288(112954). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954.

Humphreys, K. L., LeMoult, J., Wear, J. G., Piersiak, H. A., Lee, A., & Gotlib, I. H. (2020). Child maltreatment and depression: A meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 102, 104361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104361.

Iob, E., Frank, P., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Levels of severity of depressive symptoms among at-risk groups in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2026064. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.26064.

Janiri, D., Moccia, L., Dattoli, L., Pepe, M., Molinaro, M., De Martin, V., & Sani, G. (2021). Emotional dysregulation mediates the impact of childhood trauma on psychological distress: First Italian data during the early phase of COVID-19 outbreak. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 55(11), 1071–1078. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867421998802.

Ledur, J., & Rabinowitz, K. (November 23, 2022). There have been more than 600 mass shootings so far in 2022. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2022/06/02/mass-shootings-in-2022/.

Liel, C., Ulrich, S. M., Lorenz, S., Eickhorst, A., Fluke, J., & Walper, S. (2020). Risk factors for child abuse, neglect and exposure to intimate partner violence in early childhood: Findings in a representative cross-sectional sample in Germany, Child Abuse & Neglect, 106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104487.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavior Research Therapy, 33, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u.

Martins, C. M. S., Baes, C. V. W., de Carvalho Tofoli, S. M., & Juruena, M. F. (2014). Emotional abuse in childhood is a differential factor for the development of depression in adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(11), 774–782. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000202.

Martins-Monteverde, C. M. S., Baes, C. V. W., Reisdorfer, E., Padovan, T., de Carvalho Tofoli, S. M., & Juruena, M. F. (2019). Relationship between depression and subtypes of early life stress in adult psychiatric patients. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(19). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00019.

Matthews, T., Danese, A., Wertz, J., Ambler, A., Kelly, M., Diver, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (2015). Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: A longitudinal cohort study. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.008.

McLaughlin, K. A., Conron, K. J., Koenen, K. C., & Gilman, S. E. (2010). Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: A test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychological Medicine, 40, 1647–1658. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992121.

Moretti, M. M., & Craig, S. G. (2013). Maternal versus paternal physical and emotional abuse, affect regulation and risk for depression from adolescence to early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.09.015.

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., Vos, T., & Tomlinson, M. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9, e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349.

Nöthling, J., Suliman, S., Martin, L., Simmons, C., & Seedat, S. (2019). Differences in abuse, neglect, and exposure to community violence in adolescents with and without PTSD and depression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(21-22), 4357–4383. https://doi.org/10.1177/088620516674944.

Pearlin, L. I. (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30(3), 241–256.

Pietrabissa, G., & Simpson, S. G. (2020). Psychological consequences of social isolation during COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(2201). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02201.

Powers, A., Ressler, K. J., & Bradley, R. G. (2009). The protective role of friendship on the effects of childhood abuse and depression. Depression and Anxiety, 26, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20534.

Rapee, R. M., Oar, E. L., Johnco, C. J., Forbes, M. K., Fardouly, J., Magson, N. R., & Richardson, C. E. (2019). Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behavior Research and Therapy, 123, 103501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501.

Riiser, K., Helseth, S., Haraldstad, K., Torbjornsen, A., & Richardsen, K. R. (2020). Adolescents’ health literacy, health protective measures, and health-related quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLOS One, 15(8), e0238161. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238161.

Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T. K., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., & Goldbeck, L. (2017). International development and psychometric properties of the Child and Adoelscent Trauma Screen (CATS). Journal of Affective Disorders, 210, 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.12.040.

Salazar, A. M., Keller, T. E., & Courtney, M. E. (2011). Understanding social support’s role in the relationship between maltreatment and depression in youth with foster care experience. Child Maltreatment, 16(2), 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511402985.

SAS [compter program]. Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2013.

Schulz, P., Beblo, T., Ribbert, H., Kater, L., Spannhorst, S., Driessen, M., & Henning-Fast, K. (2017). How is childhood emotional abuse related to major depression in adulthood? The role of personality and emotion acceptance. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.022.

Schweizer, S., Gotlib, I. H., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2020). The role of affective control in emotion regulation during adolescence. Emotion, 20(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000695.

Shah, K., Mann, S., Singh, R., Bangar, R., & Kulkarni, R. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of children and adolescents. Cureus, 12(8), e10051. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.

Sheikh, M. A. (2018). Childhood physical maltreatment, perceived social isolation, and internalizing symptoms: A longitudinal, three-wave, population-based study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1090-z.

Sprang, G., & Silman, M. (2013). Postraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 7, 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22.

Taylor, M. R., Agho, K. E., Stevens, G. J., & Raphael, B. (2008). Factors influencing psychological distress during a disease epidemic: Data from Australia’s first outbreak of equine influenza. BMC Public Health, 8, 347. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-347.

Trucco, E. M. (2020). A review of psychosocial factors linked to adolescent substance use. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 196, 172969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbb.2020.172969.

Trucco, E. M., Cristello, J. V., & Sutherland, M. T. (2021). Do parents still matter? The impact of parents and peers on adolescent electronic cigarette use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 780–786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.12.002.

Usher, K., Bhullar, N., Durkin, J., Gyamfi, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Family violence and COVID-19: Increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29, 549–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12735.

Wang, S., Xu, H., Zhang, S., Yang, R., Li, D., Sun, Y., & Tao, F. (2022). Linking childhood maltreatment and psychological symptoms: The role of social support, coping styles, and self-esteem in adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1-2), NP620–NP650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520918571.

World Health Organization (2014). Global status report on violence prevention. Retrieved from:http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/en/.

World Meteoreological Organization (2021). Weather-related disasters increase over past 50 years, causing more damage but fewer deaths. Retrieved from: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/weather-related-disasters-increase-over-past-50-years-causing-more-damage-fewer.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers U54 MD012393, Subproject ID:5378]. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funder. We thank the families participating in the ACE Project, the ACE Program Coordinator, Nasreen Hidmi, and the ACE Project staff.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant numbers U54 MD012393, Subproject ID:5378]. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the funder.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.M.T. participated in the study design and coordination of the study, was involved in the interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript; N.M.F. helped to draft the manuscript and was involved in the interpretation of the data; M.G.V. assisted with data collection, performed the statistical analysis, participated in the interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript; M.K. conceived of the study and participated in the interpretation of the data; M.T.S. assisted in the study design and coordination of the study, participated in the interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures with human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional committee where the study was conducted and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent and assent was obtained from the caregivers and adolescents, respectively.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Trucco, E.M., Fava, N.M., Villar, M.G. et al. Social Isolation During the COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts the Link between Child Abuse and Adolescent Internalizing Problems. J Youth Adolescence 52, 1313–1324 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01775-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01775-w