Abstract

Predicting entrepreneurial development based on individual and business-related characteristics is a key objective of entrepreneurship research. In this context, we investigate whether the motives of becoming an entrepreneur influence the subsequent entrepreneurial development. In our analysis, we examine a broad range of business outcomes including survival and income, as well as job creation, and expansion and innovation activities for up to 40 months after business formation. Using the self-determination theory as conceptual background, we aggregate the start-up motives into a continuous motivational index. We show – based on a unique dataset of German start-ups from unemployment and non-unemployment – that the later business performance is better, the higher they score on this index. Effects are particularly strong for growth-oriented outcomes like innovation and expansion activities. In a next step, we examine three underlying motivational categories that we term opportunity, career ambition, and necessity. We show that individuals driven by opportunity motives perform better in terms of innovation and business expansion activities, while career ambition is positively associated with survival, income, and the probability of hiring employees. All effects are robust to the inclusion of a large battery of covariates that are proven to be important determinants of entrepreneurial performance.

Plain English Summary

We analyze how the motives to become an entrepreneur influence a broad range of business outcomes about 40 months after business formation. Specifically, we focus on outcomes like business survival and earnings from entrepreneurship, but also on job creation, innovation, and expansion activities. With our analysis, we add to research that focused on the question of whether start-up motives affect the probability of starting entrepreneurial activities. For our analysis, we aggregate start-up motives into a continuous motivational index alongside three motivational categories – opportunity, career ambition and necessity. We show that subsequent business performance is better, the higher individuals score on the motivational index. Effects are particularly strong for growth-oriented outcomes like innovation and expansion. Moreover, individuals driven by opportunity motives perform better in terms of innovation and business expansion activities, while career ambition is positively associated with survival, income, and the probability of hiring employees. Lastly, our analysis indicates that the necessity motive does not exert a significantly negative influence on entrepreneurial performance once the resource endowment of individuals is controlled for.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Predicting entrepreneurial performance is important, as it allows for making better occupational choices and may help avoid costly misallocations. Various individual and business-related variables are already tested regarding how they affect later business outcomes. However, evidence on the influence of the motivation to become an entrepreneur on the subsequent development as an entrepreneur is scarce. As such motivation refers to the “internal states that impel them to goal directed action” (Brody & Ehrlichman, 1998, p. 195), these kinds of motivational variables may not just affect the beginning of an entrepreneurial career but also the later progress of their firms (see, Baum & Locke, 2004). Therefore, the main aim of this paper is to investigate to what extent the specific reasons underlying the decision to engage in entrepreneurial activities significantly influence business performance in the subsequent years.

Research on motivation in the context of starting entrepreneurial activities offers a variety of concepts, with a prominent one being the push-pull dichotomy distinguishing nascent entrepreneurs into two types (e.g., Shapero, 1975; Solymossy, 1997): the first type consists of those “pulled” into entrepreneurship by choice, for instance because they aim to realize a business idea. The second type are those who feel “pushed” into entrepreneurial activities by exogenous, mostly adverse, factors, with individuals becoming entrepreneurs, for instance, due to a lack of better job alternatives (see Storey, 1991; Clark & Drinkwater, 2000; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010; Kautonen et al., 2014). The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) establishes a similar dichotomy that is a subset to the push-pull approach – it divides business founders into opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs (Reynolds et al., 2002).

Empirical research based on this binary concept often applies a parsimonious operationalization where the previous employment status is used as a proxy to distinguish between the two types. Individuals starting from unemployment are categorized as push-type entrepreneurs and individuals starting from an employed position are categorized as pull-types (see, e.g., Block & Sandner, 2009; Kautonen & Palmroos, 2010; Block et al., 2015). This research examines how such proxies influence subsequent entrepreneurial development. Its finding is straightforward: individuals coming from an employed position outperform individuals coming from unemployment (Hessels et al., 2008). However, it remains unclear whether such information is a viable proxy for start-up motivation.

Therefore, others introduce a multidimensional concept, surveying individuals about their start-up motivation (see inter alia Carter et al., 2003), among them economic motives, like financial success, and non-economic motives, like independence or the willingness to innovate. Using these reasons, most studies concentrate their analysis on the extent to which these motivational factors influence the probability of actually starting a business (see Murnieks et al., 2020). The best of our knowledge, longitudinal approaches have not been employed to determine if the directly measured start-up motives affect the subsequent entrepreneurial development of entrepreneurs, where performance is measured by a variety of outcomes that also indicate the growth potential of their firms.

We close this gap by using genuine information on start-up motives. The central research question of our approach is to investigate whether these specific motives to start a business actually influence the subsequent entrepreneurial performance. For this, we combine survey data with administrative data from the Federal Employment Agency in Germany. Our dataset comprises rich information about individuals who started their business either from a non-unemployed position or out of unemployment and who were asked about their motives to venture a business. We use a sample of 2034 entrepreneurs whose business status was followed for the first 3.5 years after launching their businesses. Applying the theoretical concept that is based on self-determination theory by Ryan and Deci (2000), we sort various start-up motives according to their perceived locus of causality. This sorting allows us to aggregate the motivational items we observe into a motivational index as well as into three different motivational categories that we term opportunity, career ambition, and necessity. We then investigate to what extent the motives captured in the index and the three motivational categories influence various performance measures, comprising subsequent firm survival, entrepreneurial income, and job creation, as well as expansion and innovation activities. By further differentiating between start-ups out of non-unemployment and start-ups out of unemployment, we are then also able to ask whether the previous employment status is a helpful proxy for motivation.

With our analysis, we contribute to the literature in three ways: First, by making use of longitudinal data and a large number of control variables, we are able to examine whether start-up motives unfold an effect on a larger set of entrepreneurial performance indicators in the medium run, including measures of firm growth (see, e.g., Baum & Locke, 2004), an increasingly important measure of entrepreneurial success. Understanding antecedents of firm growth is particularly critical (Douglas, 2013) given that new firms only start affecting broader economic development and jobs once these firms begin to grow (Haltiwanger & Miranda, 2013).

Secondly, adopting the self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci (2000) allows us to extend the push-pull dichotomy. On the one hand, we transform items that capture start-up motives to a continuous motivational index; on the other hand, we are able to extend the existing dichotomous approaches (Solymossy, 1997; Reynolds et al., 2002) by distinguishing between three motivational categories. This further distinction enables us to investigate what kind of start-up motives specifically influence which medium-term performance measures, e.g., job creation versus innovation activities.

Third, while earlier approaches use information about the previous employment status (see, e.g., Block et al., 2015) i.e., creating the new business out of unemployment or employment, as a proxy for start-up motives, we are able to disentangle the employment information from individual start-up motives. Doing so clarifies why it is important to use genuine information on start-up motives. This adds an important aspect to the literature as it allows for analyzing the distribution of start-up motives as well as their influence on firm performance in both groups.

2 Previous research and conceptual framework

2.1 Previous empirical research

Earlier research investigating what motivates individuals to start an own business identifies six factors (Carter et al., 2003): innovation, independence, recognition, roles, financial success, and self-realization,Footnote 1 of which independence, financial success, and innovation are found to be the three most important motives for becoming an entrepreneur.Footnote 2

However, to the best of our knowledge, only two empirical studies make use of such a multidimensional concept when investigating the influence of start-up motives on firm performance and, thus, to a certain extent, are related to our approach. Birley and Westhead (1994) identify, based on 23 motivational items observed among 400 business founders, seven factors. In their cross-sectional analysis, they report that the various reasons for starting a business weakly correlate with firm performance measured by sales and employment levels. Only for a small minority, whom they label as confused business founders, they observe less job creation in their firms. They conclude that start-up motives have a minimal influence on subsequent firm performance. This outcome is seen as one potential explanation of why there is no further analysis of whether start-up motives affect subsequent firm development (Carsrud & Brännback, 2011). A second reason could be that there are limited data available that include start-up motives in connection with later firm performance.Footnote 3 The study by de Vries et al. (2020) addresses the second issue and uses three different measures for necessity motives, among them a measure that is based on several items capturing various start-up motives. They analyze the relationship between these start-up motives and the annual turnover for a stock of solo self-employed (comprising not only founders of solo activities but also established solo self-employed) and find that necessity-driven solo self-employed perform worse in terms of annual turnover than those who are driven by opportunity motives. Importantly, de Vries et al. (2020) interpret their results in the direction that “the borderline between necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship... is less clear-cut than previously assumed” (p. 458).

Thus, analyses of how start-up motives, directly measured by corresponding items, influence the later firm performance are the exception. What is more common in the literature is to proxy start-up motives by the employment status prior to the start-up or related information such as having left the previous job voluntarily or involuntarily.Footnote 4 These studies show that previously unemployed entrepreneurs are more likely to experience subsequent business failure (e.g., Carrasco, 1999; Pfeiffer and Reize, 2000). If their businesses do survive, oftentimes they fail to create further jobs (Shane, 2009), pursue less profitable business opportunities earning smaller income (Block & Wagner, 2010; Andersson & Wadensjö, 2007; Hamilton, 2000), invest smaller amounts of capital (Santarelli & Vivarelli, 2007), or create more marginal businesses (Vivarelli & Audretsch, 1998).

Further studies — using the reason for job termination as a proxy — find that after controlling for educational aspects, there is no difference in the exit rates from self-employment between the two types of entrepreneurs (Block & Sandner, 2009; Block & Wagner, 2010). They also reveal that chances of being a push-type entrepreneur increase with age (see also, Kautonen et al., 2014; Verheul et al., 2016), while Block et al. (2015) show that push-type entrepreneurs are more likely to pursue a strategy of cost leadership instead of a differentiation strategy (as pull-type entrepreneurs do). Van Stel et al. (2018) use six dummy variables related to the question of whether individuals ended their previous job voluntarily or involuntarily and analyze how these are related to the long-term development of their entrepreneurial earnings. They find that individuals who started their entrepreneurial career because their previous job ended involuntarily tend to realize lower earnings than entrepreneurs who left their previous job voluntarily. Thus, these studies typically find considerable differences in later firm performance when comparing entrepreneurs based on how they left their previous employment status, where this information is used as a proxy for the motivation of these entrepreneurs.

Our analysis is developed in a way such that we are able to close this research gap. More specifically, instead of focusing on the previous employment status or related information, we use motivational items that earlier research identifies as being relevant for starting an entrepreneurial career. Based on the self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci (2000), which we explain in the next section, we transform the items capturing start-up motives into a motivational index and into three motivational categories. We then empirically investigate their influence on business performance in the medium run.

2.2 The influence of start-up motives on long-term business performance

Individuals decide to become entrepreneurs for very different reasons,Footnote 5 with previous research emphasizing that start-up motives affect the probability of actually starting entrepreneurial activities (Kolvereid & Isaksen, 2006). Krueger et al. (2000) postulate that such reasons are important after the businesses are launched as well, potentially helping to predict entrepreneurial performance and firm development. This is because start-up motives may also influence later behavior as entrepreneurs,Footnote 6 specifically how entrepreneurs identify opportunities and how they plan to develop and manage their firms in the postlaunch phase (see also Locke and Baum, 2007; Schjoedt & Shaver, 2007).

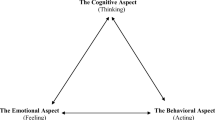

There is a great variety of approaches analyzing how motivation in general relates to subsequent performance. For instance, based on self-determination theory, Ryan and Deci (2000) analyze processes of self-motivation. One key insight of their seminal paper is that there are contrasting types of extrinsic versus intrinsic motivations describing how self-determined the behavior of an individual is based on each type of motivation. We adopt the model of Ryan and Deci (2000) to entrepreneurship and differentiate between the various start-up motives according to their definition of the perceived locus of causality. This concept of describes (see also Fig. 1) whether individuals perceive their behavior as being caused by internal reasons (internal perceived locus of causality) or external reasons (external perceived locus of causality).Footnote 7

Relationship between the locus of causality of motives and motivational categories. Note: Based on the self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci (2000), the figure links the collected start-up motives to the motivational categories with their loci of causality

This allows us to connect the self-determination theory to the existing variation of start-up motives. Generally speaking, individuals who act with an internal perceived locus of causality are themselves the initiators of their behavior, for instance because they want to realize a business idea or because they want to be their own boss. These individuals are considered to have motives leading to highly self-determined behavior. At the other end of the motivational continuum are individuals who make such an occupational choice because they lost their previous job and are unable to find a new one, thus having an external perceived locus of causality. They may still have a preference for a job with regular pay (see the discussion in Caliendo et al., 2020a) and are less guided by future perspectives as an entrepreneur. This is why they are considered to have motives leading to less self-determined behavior. They complete their entrepreneurial tasks in reaction to external pressure.

These varying start-up motives are expected to influence subsequent firm performance (Brody & Ehrlichman, 1998; Krueger et al., 2000). More specifically, start-up motives are expected to directly influence the plans of the entrepreneurs when they aim to realize their business opportunity and prepare their start-ups, mirroring their goal orientation. Later on, start-up motives will either directly or indirectly (through the aim of realizing the made plans) influence their effort levels and task performance as entrepreneurs when they execute their plans while managing their businesses after start-up (see inter alia Brinckmann et al., 2010). Thus, start-up motives and, related to them, goal orientation will affect how goal-relevant activities are mastered and needed actions are implemented, influencing how persistently entrepreneurs are executing their new business strategies (see Locke & Latham, 2002), ultimately influencing subsequent firm performance (see Locke & Latham, 1990). Hence, we expect that start-up motives will affect all performance measures we employ. We hypothesize:

- H1::

-

The more internal the perceived locus of causality of the start-up motives is, i.e., the higher individuals score in the motivational index, the better the subsequent firm performance will be in terms of survival, entrepreneurial income, and job creation, as well as expansion and innovation activities.

The self-determination theory of Ryan and Deci (2000) also allows for a more nuanced differentiation between various motivational categories. As mentioned earlier, start-up motives that have an internal perceived locus of causality can be divided into two motivational categories. There exist motives like implementing an own idea or perceiving a market opportunity, mirroring the need for competence and relatedness. These are “task-related” motives referring to reasons why individuals are interested in entrepreneurial activities per se and derive satisfaction from realizing them (for an overview see Fig. 1, which we use in Section 3.2 to connect the observed motivational items to their locus of causality). We term these – similar to the GEM approach – as opportunity motives. There is a second type of motives, reflecting independence or financial success. These comprise “self-related” motives where certain achievements (such as higher income) are emphasized as performance goals. Thus, individuals are motivated by the “most autonomous form of extrinsic motivation .... Actions characterized by integrated motivation share many qualities with intrinsic motivation although they are still considered as extrinsic” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 73), because they are done to achieve goals like financial success that are external to the entrepreneurial activities per se. In this case, completing entrepreneurial tasks is the mediating factor to realize the desired goal. We term these types of motives as career ambition. For the third motivational type, the perceived locus of causality is external. Start-up motives like the unavailability of a regular job or a recommendation by others to try out entrepreneurship are motives that are related to external pressure. Entrepreneurial tasks are rather fulfilled in order to react to the existing pressure. Similar to the GEM approach, we term this third kind of start-up motive necessity.

Psychological research postulates that further differentiating between motivational categories matters for how entrepreneurial tasks are performed and how motivation influences different performance outcomes (Locke & Baum, 2007). Entrepreneurs driven by opportunity motives will concentrate on tasks that provide a reward to goals like realizing their own business idea. Such goals are associated with the intrinsic motivation and the capacity to turn their knowledge into new ideas. Therefore, opportunity motives should positively influence performance measures that are related to these tasks, like being innovative or expanding the business to new fields or to new regions. Rewards like higher income, firm growth, and even business survival are of secondary relevance for individuals motivated by the entrepreneurial task itself.Footnote 8 Thus, these performance measures should be unaffected by opportunity-type motivations.

- H2a::

-

The higher individuals score in opportunity, the better their subsequent firm performance in terms of innovation and expansion activities.

Entrepreneurs with career ambition–driven motives will concentrate on tasks that help achieve their self-set goals, for instance of higher income or of remaining an entrepreneur (Baum and Locke, 2004). They typically aim for rather doable tasks. Therefore, such motives should positively influence performance measures, like the survival probability or the generated incomes. The same holds true for performance measures related to hiring employees, when these serve the self-set goal, for instance of increasing income (see also; Dunkelberg et al., 2013). Innovation activities or an expansion of their business are rather of secondary relevance.

- H2b::

-

The higher individuals score in career ambition, the better their subsequent firm performance in terms of survival, income, and hiring employees.

For individuals driven by necessity motives, for instance by the unavailability of a regular job, such motives may be connected with a less genuine interest in realizing a market opportunity or less ambition to make an entrepreneurial career. Therefore, individuals exclusively driven by such motives may put less effort into running their business and may give their businesses up more easily if a job with regular pay is offered, reducing their survival probability, or, if they remain in business, that their entrepreneurial incomes will be negatively affected. These individuals are more likely to engage in rather simple ventures making use of a replication strategy (Block et al., 2015), thus being less likely to introduce an innovation (Alvarez & Barney, 2007). They are also more likely to keep their businesses small (Kautonen et al., 2014), given the complexity of expanding or employing others in the business. We derive the following hypotheses:

- H2c::

-

The higher individuals score in necessity, the worse their subsequent firm performance will be in terms of survival, entrepreneurial income, and job creation, as well as expansion and innovation activities.

Overall, this concept proposes that start-up motives influence either directly or indirectly the subsequent firm performance. If the motives unfold indirect influence, this might happen for instance through plans for the further business development. We discuss such potential mechanisms in Section 4.4.

3 Data, motivational items, and descriptives

We start with a data description, before presenting our motivational items and the construction of our motivational index. We then discuss differences in the motives between formerly unemployed and non-unemployed individuals before introducing the explanatory variables used as covariates. At the end of the section, we briefly present selected summary statistics on the outcome variables.

3.1 Data creation and estimation sample

The data set we use is a longitudinal extension of a telephone survey that was initially collected by Caliendo et al. (2015). They created a unique data set that allows for a comprehensive and in-depth comparison between subsidized start-ups out of unemployment and non-subsidized start-ups out of non-unemployment. Based on different data sources, they drew representative random samples of subsidized and non-subsidized founders who started a full-time business in the first quarter of 2009 in Germany. The cohort of subsidized founders consists of initially unemployed individuals who received a start-up subsidy (Gruendungszuschuss) from the Federal Employment Agency,Footnote 9 while non-subsidized (regular) start-ups consist of founders who were not unemployed directly prior to start-up and, consequently, did not receive the subsidy (see Caliendo et al., 2015, for details on data construction). While the data was initially collected to evaluate the effects of the start-up subsidyFootnote 10 and, hence, start-ups out of unemployment are over-represented, it is also an ideal dataset for analyzing the performance of business start-ups in Germany as it contains a large set of informative covariates and interesting outcomes.

The business founders in our sample were surveyed twice. The first interview (wave 1) was conducted around 19 months after start-up and focused on an extensive list of start-up characteristics, socio-demographics, previous labor market experiences, and intergenerational transmissions, as well as their motives to start their business in the first place. In addition to their labor market status, and conditional on the ongoing business activity of their initial start-up from the first quarter in 2009, they were also interviewed about their business performance across various dimensions, including the number of jobs created as well as innovation and expansion activities. Figure A.1 in the Online-Appendix shows that 2306 valid interviews were completed with subsidized founders from unemployment and 1529 interviews with regular founders from non-unemployment. Caliendo et al. (2020b) amend the data with a second interview (wave 2) that extends the observation window to 40 months after start-up. This allows us to analyze the influence of motives on business outcomes up until 3.5 years after business formation for 2034 panel observations available in wave 2 (1300/734 subsidized/regular founders). The distribution of two-thirds of start-ups from unemployment and one-third of start-ups from non-unemployment is due to the different foci during the data generation process and does not represent population shares (where the ratio in 2009 was 46% from unemployment and 54% from non-unemployment). We keep this in mind when analyzing the two groups and argue in Section 4.5 that this does not harm our interpretation. Out of the 2034 panel observations, roughly 39% (796) are female, which is very close to the share of female founders in the general population of entrepreneurs in Germany (41% in 2009, Federal Statistical Office of Germany, 2018).

Respondents participating in both interview waves (panel sample) are, on average, older, have a higher educational and professional background, had higher earnings in the past, and experienced less lifetime unemployment compared to the full sample in wave 1. Since panel attrition also induces a (very) weak selective bias in our outcome variables, we follow Caliendo et al. (2020b) and precautionary use a weighting procedure in order to correct for selective panel attrition.Footnote 11

3.2 Start-up motives and motivational index

Motivational items

In the design of the items to reveal the motives of individuals to start a business, two lines of thought are combined. First, a simple version of the concept developed by Carter et al. (2003) is applied with respect to those motives that have an internal locus of causality for becoming an entrepreneur. Four items are introduced, i.e., “desire to be one’s own boss,” “discovery of a market niche,” “desire to earn more money,” and “realization of a business idea.” With respect to the items capturing an external locus of causality in the motivation to start a business, three additional items are introduced, based on previous research (Storey, 1991; Clark and Drinkwater, 2000; Caliendo & Kritikos, 2010), i.e., “unavailability of a regular job,” “recommendation by others,” and “discrimination at the previous job.” Thus, in total, respondents were given seven statements concerning their motivation for starting their business in the first quarter of 2009. For each of these start-up motives, individuals were asked to rate to what degree it applied to them on a Likert-scale ranging from “1” (does not apply at all) to “7” (applies entirely).Footnote 12 Column (1) of Table 1 shows the mean values of the seven items indicating that independence, i.e., “desire to be one’s own boss,” is the motive that receives strongest support from business founders, followed by innovation (“realization of a business idea”) and financial success, thus fully confirming the earlier results of (Carter et al., 2003). Among the items for involuntary transitions, “unavailability of a regular job” is the most important reason for a transition to entrepreneurship.

Linking the motivational items to various categories of motivation

The approach of Ryan and Deci (2000) differentiates between various categories of motivation. We link these categories of motivation, as visualized in Fig. 1, to the start-up motives in the context of entrepreneurship. Start-up motives that have an internal perceived locus of causality can be divided into two motivational categories, as described in Section 2.2. Motives like implementing an own idea or perceiving a market opportunity refer to reasons why individuals are interested in entrepreneurial activities per se. The second motivational type with an internal perceived locus of causality consists of items like independence or financial success. These are again self-related motives where certain achievements are emphasized as performance goals. For the third motivational type, the perceived locus of causality is external (Fig. 1). Start-up motives that were used in the survey, like the unavailability of a regular job, discrimination at the previous job, or a recommendation by others to try out entrepreneurship, are motives that are related to external pressure or external suggestion. Entrepreneurial tasks are rather fulfilled in order to react to such external pressure, and the motivation of becoming an entrepreneur is extrinsic.

Motivational index

Having linked the surveyed start-up motives to various motivational categories, for the further analysis, we construct a motivational index that aggregates all motives into one continuum. In order to do so, we sum up the four items that indicate an internal perceived locus of causality with the reverse of the three items indicating an external perceived locus of causality, i.e.,

Figure A.2a in the Online-Appendix shows the distribution of the motivational index. With an average of 4.6 (and a standard deviation of 1.01), the distribution is slightly skewed to the right, but we observe individuals with a wide range of answers, starting at the lower end of the distribution with individuals for whom extrinsic motives are most relevant. For the later analysis, we mean standardize the motivational index to ease interpretation and also split the sample at the median (4.7) into individuals who score “high” (above median) and “low” on this index when we check for non-linearities in the effects.

Three motivational categories

In addition to the motivational index, the approach of Ryan and Deci (2000) further allows for combining items into three motivational categories. As further shown in Fig. 1, for those items with an internal perceived locus of causality, we are able to differentiate between two motivational categories. In the first category, we classify the aim to “realize a business idea” and “having identified a market niche” as opportunity motives; these are motives with an intrinsic motivation. The second category combines the items “be one’s own boss” and “desire to earn more money” to the motive career ambition; these are motives with an already extrinsic motivation, but a high level of self-motivation. In addition, we integrate those motives that have an external locus of causality for entrepreneurship, i.e., the three items “unavailability of a regular job,” “recommendation by others,” and “discrimination at the previous job” in a third category that we term necessity, where motivation is also extrinsic, but has a low level of self-motivation. Comparing the three motivational categories (see again Table 1), career ambition is the most relevant one with a mean of 4.19, followed by opportunity (3.48) and necessity (2.35). Individuals start as entrepreneurs more often for career than for opportunity reasons.Footnote 13 Such a differentiation allows a more nuanced investigation (beyond the existing dichotomous approaches) regarding the extent that start-up motives unfold differing influences on the subsequent entrepreneurial performance. Accordingly, we will also introduce these motivational categories as alternative explanatory variables in our empirical analysis.

Further individual and business characteristics as control variables

Given that our research aim is to identify the influence of start-up motives on entrepreneurial performance, other individual- and business-related variables that are known to affect entrepreneurial outcomes (Shane et al., 2003) need to be controlled for. Such variables include personal characteristics, for instance the age (Kautonen et al., 2014) or gender (Fairlie & Robb, 2009) of the entrepreneur, the human capital of the entrepreneur (Unger et al., 2011), and potential intergenerational transmission, for instance via parental self-employment (Dunn & Holtz-Eakin, 2000). They further include the labor market history, for instance the duration of the last dependent employment (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) or the income from last dependent employment (Astebro & Chen, 2014). There are also well-known business-related characteristics, like the industry-specific experience before start-up (Bosma et al., 2004) and the financial capital invested when the firm was launched (Holtz-Eakin et al., 1994; Blanchflower & Oswald, 1998), that influence later firm development, as well as local macroeconomic conditions (Millán et al., 2012; Sedlácek & Sterk, 2017). Our data allows us to include a very wide range of these variables as listed in Table A.2 in the Online-Appendix.

Distribution of motives between founders from (un-) employment

Earlier research connects the previous employment status with the motivation for starting a business. This is based on the assumption that entrepreneurs coming from unemployment would perceive the locus of causality of their motivation to become an entrepreneur as external, while entrepreneurs coming from a non-unemployed position would perceive the locus of causality of their motivation to become an entrepreneur as internal. We are able to test this assumption based on the motivational items in our data. Columns (2) and (3) of Table 1 show once again the mean values in each group, column (4) reports the test on mean equality. It shows that regular start-ups (from non-unemployment) score significantly higher on the motivational index compared to start-ups from unemployment (4.78 vs. 4.50, p-value: 0.00). Looking at the distribution of the index in Figure A.2b in the Online-Appendix shows that there is more density mass for start-ups from non-unemployment at the higher end of the index, while start-ups from unemployment have more density mass at the lower end of the distribution and, consequently, the corresponding Kolmogorow-Smirnov test on the equality of both distributions is rejected (p-value: 0.00). However, what we also observe is that the distribution between the two groups largely overlaps. Both groups differ mainly in the items “unavailability of regular job,” “discrimination at previous job,” and “recommendation by others.” These three items are summarized in necessity, where unemployed founders score, with 2.59, significantly higher than regular founders, with 1.86 (p-value: 0.00). We do not find significant differences for the items “desire to be one’s own boss,” “desire to earn more money,” and “discovery of a market niche” (although the p-value here is 0.11), while even significantly more individuals coming from unemployment state that they aimed to “realize a business idea.” This leads to the fact that we do not find any significant differences in career ambition between both groups, while founders from unemployment score higher in opportunity than regular founders (3.56 vs. 3.34, p-value: 0.04). Overall, we observe that business founders coming out of unemployment are driven by relatively similar motives as regular business founders.

3.3 Selected descriptives for outcomes

We consider four different kinds of outcome variables at the end of our observation period in t40: (i) survival, (ii) income, (iii) job creation, and (iv) growth-oriented outcome variables including innovation and expansion activities. For the outcomes in (ii)–(iv), we restrict our sample to founders who are still self-employed. Income is measured as monthly net earned income from self-employment (in euros, inflation-adjusted to 2010 levels following the Federal Statistical Office, 2014). With respect to job creation, we consider the extensive margin, i.e., the share of businesses with at least one employee (“1” if at least one employee, “0” otherwise). For innovation activities, we observe whether founders have filed at least one patent application or applied for trademark protectionFootnote 14 since start-up (“1” if yes, ‘0’ otherwise). For expansion activities, we observe whether businesses expanded to new fields or to new regions (respectively “1” if yes, ‘0’ otherwise).Footnote 15

Table A.1 in the Online-Appendix shows that individuals who score high on the motivational index (i.e., above the median) have a higher probability to survive (75%) than business founders who score low on the motivational index (66%). Not only do they have significantly higher income, but they are also more likely to have employees (52% vs. 42%), to apply for a patent or trademark protection (16% vs. 6%), to expand to new fields of business (30% vs. 20%), or to expand to new regions (12% vs. 5%). Interestingly, for the latter three outcomes, we are also able to observe whether individuals already had plans to do so in wave 1 (after 19 months). We can see that business founders scoring high in the index already had the intention to expand and innovate before they actually expanded. With respect to field/regional expansions, the respective shares for higher motivated founders with a plan are 55%/26%, while it is only 44%/14% in the group of lower motivated founders. In terms of innovation activities, the comparison is 12% (high) vs. 5% and all these differences are statically significant at the 1%-level. We return to this in Section 4.4 when we discuss potential mechanisms, further describing the relationship between start-up motives and performance outcomes.

4 Empirical analysis

4.1 Estimation strategy

To test the influence of start-up motives on subsequent business development 40 months after business formation, we apply logit models for the binary outcome variables as well as OLS regressions for the continuous outcome variable. In order to test which business outcomes are affected by start-up motivations, we control for an extensive set of individual and business-related characteristics as well as local macroeconomic conditions that are shown to matter for entrepreneurial development (as discussed in Section 2.2). We employ logit estimations for business survival and an employer dummy variable (taking the value “1” if the business has at least one employee and “0” otherwise), as well as four indicators of innovative capacity and business expansion. The following logit regression on survival with the same business is exemplary for all binary outcome variables:

where we operationalize Motivesi in two different versions based on either the motivational index or the three motivational categories career ambition, opportunity, and necessity defined in Section 3.2. Xi stands for the vector of control variables. These include personal characteristics Ai (age categories, children categorized, marital status, nationality, living in East Germany), human capital Bi (school achievement, professional education), intergenerational transmission Ci (parents born abroad, parental self-employment, business takeover from parents, school achievement of father, father of respondent employed at age 15), labor market history Di (duration of last dependent employment right before start-up, monthly net income from last dependent employment categorized, employment experience before start-up), and local macroeconomic conditions Ei (vacancies related to stock of unemployed, unemployment rate, real GDP per capita in 2008), as well as business-related characteristics Fi (sector, industry-specific experience before start-up, capital invested at start-up categorized, capital at start-up consisted entirely of own equity). When examining the influence of motives on income, we use an OLS regression with the same set of covariates.

4.2 Main results

Motivational index

Table 2 shows our main regression results. For all outcome variables, we start by presenting the raw influence of our motivational operationalizations; i.e., we estimate a model without any other explanatory covariates, before moving on to a model including all other explanatory covariates. For all binary outcomes, the numbers presented are the average marginal effects of increasing the respective index by one standard deviation. For example, column (1) shows that a one standard deviation (SD) increase in the motivational index leads to a 5.5 percentage points higher survival probability. After controlling for the full set of covariates, the effect decreases to 3.5 percentage points. This relates to a relative effect of 5.0%, which is economically relevant and statistically significant. It means that start-up motives have explanatory power for survival in month 40, even after controlling for a large set of covariates that are proven as key determinants in the literature.

Similarly, we observe a significant influence of motivation on all other outcome variables. The higher individuals score on the motivational index, the higher is the income they generate through their activities and the more likely they are to employ others in their firm. The economic magnitude is about 5.9% for income and 6.4% for employees (controlling for all other covariates), becoming even larger for the further outcome variables. A one SD increase in the motivational index is associated with an increase in the expansion to new fields by 3.4 percentage points (13.2%), a regional expansion by 3.0 percentage points (30.6%), and in the probability that they file a patent or apply for trademark protection even by 6.0 percentage points, which is equivalent to 51.9%. Thus in support of Hypothesis 1, the motivational index has a significantly positive influence on a broad spectrum of entrepreneurial performance measures even 3.5 years after businesses were ventured and after controlling for a large set of relevant covariates. Interestingly, the effects are particularly strong for the growth-oriented business outcomes, such as innovation and expansion activities, where we observe that adding control variables in the estimation only reduces the overall effect size to a minor extent.

Motivational categories

Turning to the three motivational categories, a more differentiated picture is revealed, where the influence of the categories strongly varies by outcomes. Three interesting results emerge: the motivational category career ambition, confirming Hypothesis 2b, significantly increases the survival probabilities, the likeliness of hiring employees, as well as income from entrepreneurship. For instance, for business survival, a one standard deviation increase (1.75) in career ambition is associated with a higher survival probability of 3.6 percentage points (or 5.1%). The relative effect on income is 11.6% and the effect on having employees is 6.1%.

When looking at the next motivational category — opportunity — we do not see any statistically significant positive effects on these outcome variables; on the contrary, a one standard deviation increase in the opportunity motive is even associated with a significant reduction in income by 6%. However, the more entrepreneurs are driven by opportunity, the higher is their likelihood of having filed for a patent or applied for trademark protection (a one SD increase is associated with + 5.7 percentage points/+ 49.1%), and the more likely they are to expand to new fields of business (+ 5.2 percentage points/+ 20.1%) mostly confirming Hypothesis 2a. The latter two outcome variables are unaffected by career ambition. The only outcome variable that is positively influenced by both categories is the regional expansion (albeit it is only significant at the 10 percent level for the category career ambition). A one SD increase in opportunity (career ambition) is associated with a 31.4% (15.1%) higher probability to expand the businesses to regions other than their home region. Finally, we also observe interesting results with respect to necessity driven entrepreneurs. While higher necessity motivation was expected to worsen firm development, we see significant differences for survival, income, employees, and innovation only in the estimations without control variables. Once these controls are added, the negative influence on entrepreneurial development vanishes, thus failing to confirm Hypothesis 2c.

Control variables

With regard to the control variables, we present results in Table A.3 in the Online-Appendix for the exemplary outcome of hiring employees.Footnote 16 We observe that most of the control variables unfold an influence in the expected direction. For instance, entrepreneurs are significantly more likely to hire employees in their firms if they achieved higher education levels in terms of schooling or professional education, thus with more human capital. The same applies if they had no unemployment experience, took over the business from their parents, or invested large amounts of capital. Furthermore, they were less likely to hire if they gained their industry-specific experience in their hobby and not through employment or self-employment experience. Among industries, the hiring decision is positively influenced when they started in the manufacturing sector. Hence, the human, working, and financial capital of these entrepreneurs also matters for the hiring decision.Footnote 17 Having controlled for these variables, the motivation to become an entrepreneur still unfolds a significant influence on this entrepreneurial performance measure.

4.3 Robustness analysis

We turn now to consider the robustness of our conclusions to a variety of important issues. The results are reported in Tables A.4 and A.5 in the Online-Appendix.

Non-linearities

In panel A of Table A.4, we test the robustness of our results with respect to non-linearities using a dummy variable based on the motivational index, taking the value “1” if the index is above the median and “0” otherwise. The coefficients for all outcome variables remain significant and become larger in magnitude. For example, the income for individuals who score above the median in the motivational index is €277 (11.4%) higher compared to individuals who score below the median. Panel B divides the motivational index into terciles and it can be seen that the positive effects are more strongly driven by individuals in the highest tercile. Panel C replicates the first exercise for the three motivational categories and creates dummy variables if individuals score above the median. Magnitudes get larger once again and the only remarkable difference to the results in Table 2 is that individuals who score above the median in necessity have significantly lower income by 211€ compared to people who score below the median. Overall, the results are robust and seem to be roughly linear.

Panel attrition weights

In panel A of Table A.5, we replicate the analysis from Table 2 without using panel attrition weights (see Section 3.1 for a discussion). Coefficients change only slightly. Variables that had been significant in the main estimation remain significant. Hence, the results are robust with respect to attrition weights.

Results from a factor analysis

To check whether the results are driven by the manual construction of our motivational index, we also run a factor analysis.Footnote 18 Panel B of Table A.5 shows that the results are essentially the same as those in Table 2.

Results for both groups of founders

To investigate whether the results are driven by the group of founders from unemployment or non-unemployment, we also estimate the effects for both groups separately in panels C (from unemployment) and D (from non-unemployment) in Table A.5. It can be seen that the effects are quantitatively similar in both groups. The relative effects are very similar for survival, patents, and income, although the latter is not statistically significant for business founders from non-unemployment (which might be due to the smaller sample size). For hiring employees, we find a larger relative effect among the individuals coming from unemployment; for field expansion, it is the other way around and neither effect is significant in the respective other group. Finally, for regional expansion, the relative effect is much larger (51.9%) among individuals from non-unemployment when compared to the unemployment group (31.7%). Overall, we see that start-up motives unfold similar influences on firm performance in both groups. Business founders out of unemployment similarly perceive an internal locus of causality when they become entrepreneurs as business founders from non-unemployment, and for those who do so, the corresponding start-up motives improve the later performance of their businesses irrespective of their previous employment status.

Timing of measurement

One concern about our analysis is the timing of measurement for our motivational variables. These were asked about in the first wave — after approximately 19 months — and this could potentially lead to a recall bias due to reverse causality, i.e., if the performance in the first 19 months influences the founders’ answer to this question, which is posed ex post. In order to address this concern, we rely on an additional data source. During the first interview in the fourth quarter of 2010, in addition to the sample above, a cohort of “fresh” business founders out of unemployment (N = 1583) was also interviewed when they launched their business.Footnote 19 They were then re-interviewed in the second wave in the third quarter of 2012, such that we can monitor their performance in the first 19 months after start-up. We can use this fresh sample to replicate our analysis for start-ups from unemployment (see panel C in Table A.5) in Table A.6 in the Online-Appendix. As can be seen, for the majority of our outcome variables (survival, income, employees, and regional expansion), we again find very similar effects as in the previous analysis. Only for field expansion and for patent and trademark applications are there no significant effects at this point of time. However, this might be due to the fact that at t19 we only observe the intermediate effects for this sample, where the influence of the motivation could not fully develop yet on those more future oriented outcomes.

4.4 Potential mechanisms

So far, we show that start-up motives have a significant influence on subsequent firm performance. We now examine whether these motives unfold such effects through a mediating variable, in particular through the behavior individuals display when they start their ventures. As indicated in Section 2.1, one potential mechanism through which start-up motives may influence firm performance might be through plans developed when businesses are launched, like for instance through making specific plans for how to grow the firm (Shane et al., 2003). Individuals who score high in the motivational index will propose more challenging plans and higher goals for the venture to grow, then put more effort into preparing their business. Individuals with an intrinsic motivation for entrepreneurship may also more likely to strive for introducing an innovation. Making ambitious plans is then an important factor for the later realization of these plans leading to stronger venture growth and a greater probability of venture survival (Baum and Smith, 2001). Thus, developing specific plans may describe the mechanism underlying how start-up motives influence subsequent firm performance.

As for the second part of this mediator path, there is an established relationship between business plans and performance outcomes of firms. This points to a mostly positive influence of plans on their later realization (see, e.g., Shane & Delmar, 2004; Chrisman et al., 2005; Gruber, 2007; Brinckmann et al., 2010). We rest on this literature, expecting that plans to grow and expand firms as well as to introduce an innovation will positively influence the probability of realizing these plans.

In order to be able to empirically conduct this mediation analysis, we use the standard three tests as recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). To do so, we use additional information on the specific plans of the surveyed entrepreneurs that were collected during the first survey in t19. Individuals were asked about their plans for expansion and innovation (see again Table A.1). Therefore, we investigate to what extent start-up motives influence such plans. More specifically, Table A.7 in the Online-Appendix shows the regression results of how motives captured in the motivational index influence these outcome variables. Again, we differentiate between its influence without and with explanatory control variables. We observe that start-up motives significantly influence the plans of these entrepreneurs (even after controlling for covariates). The higher they score in the motivational index, the more likely they have the ambition to expand their business in new fields or new regions. A one SD increase in the motivational index is associated with a 9.2%/30.5% higher probability to plan a field/business expansion. Individuals with high scores in this index are also more likely to file plans for an innovation, i.e., to register a trademark or a patent; here the relative effect for a one SD increase is 51.1%. The influence remains economically strong and statistically significant even when controlling for the extensive set of explanatory covariates.

Table A.8 in the Online-Appendix then explicitly tests whether respective plans fully or partially mediate the relationship between start-up motives and the respective outcome variables. We observe that plans for regional expansion as well as for patents or trademarks fully mediate, and for field expansion, these plans partially mediate the relationship between the motivational index and the related performance outcomes. In that sense, our analysis reveals that one potential mechanism mediating the link between motivation and firm performance is the presence of respective plans that indicate intentions toward realizing such specific firm performance for those outcome variables for which we have information on respective plans.

4.5 Limitations

In the empirical analysis, we show that the motivation to start a business has a long-lasting influence on entrepreneurial performance that is robust to various sensitivity checks. Nevertheless, there are some limitations to our study that we address here.

First, we are aware that our estimations do not necessarily reflect causal relationships, even though we include a large number of control variables. For instance, it could be claimed that we miss information on the quality of the initial entrepreneurial idea or on the level of entrepreneurial abilities that may also influence entrepreneurial performance. However, we are confident that, by controlling for education levels, for the industry context, for the previous employment exposure to the same industry, and the amount of invested capital, we are able to capture large parts of effects of the business idea’s quality on entrepreneurial performance.

Second, as our data has an unequal distribution of two-thirds of start-ups from unemployment and one-third of start-ups from non-unemployment, it clearly does not represent population shares. However, since our robustness analysis reveals very similar effects for both sub-groups, we are not concerned by this.

Third, business founders were asked approximately 19 months after starting their business about their motivation and we must assume that the stated motivations reflect those at the time of start-up. In this context, we cannot exclude that the information on initial start-up motivation is influenced by how the firm performs at the moment of the interview. However, we are able to use a second data sample where information on start-up motives was acquired at the time of business venturing. We find nearly the same influence of start-up motives on subsequent firm performance measured 1.5 years after starting the business. Unfortunately, this additional sample exclusively focuses on start-ups from unemployment, such that we cannot generalize it per se for start-ups from non-unemployment. On the other hand, we also do not have a priori reason to believe that this would work differently across the groups. In that sense, we are confident that the potential bias in our original data set is minor.

Fourth, our battery for revealing start-up motives is restricted to seven items. The limited battery is owed to the large sample that was surveyed and the extensive list of control variables. Although we are confident that we capture several important start-up motives for this transition, future research should try to extend the battery to include more items capturing further motives. This would also be in line with Dencker et al. (2021), who provide a differentiated discussion of necessity-oriented start-up motives.

5 Discussion

Literature emphasizes that the motivation of individuals for starting a business should also be important for the later performance of their firms during the initial years following business launch. However, nearly all existing empirical research analyzing the influence of start-up motives on business performance does not survey individuals about their motives. Instead, they use simple proxies like the previous employment status or related information. Yet, such approaches narrow the potential influence of start-up motives down to one dimension.

Therefore, in this paper, we make use of genuine information on start-up motives and use survey data on individuals about their reasons for the decision to become an entrepreneur. We use the self-determination theory developed by Ryan and Deci (2000) as a conceptual background that allows us to sort these start-up motives according to their perceived locus of causality and aggregate them into a continuous measure called motivational index. Our research concentrates — to the best of our knowledge for the first time — on the question of whether the continuous measure of these motives influences different dimensions of subsequent firm performance for a broad spectrum of business founders, while controlling for a large set of individual, business-related, and macroeconomic variables that previous research finds to be relevant for entrepreneurial success (Parker, 2018). Additionally, the conceptual background allows us to identify three different motivational categories that we term opportunity, career ambition, and necessity. We then investigate whether these categories influence different dimensions of subsequent firm development in different ways.

Our investigation delivers five important findings: First, start-up motives matter for later business performance, 3.5 years after the venturing of the business. The higher individuals score in the motivational index, the better their firms develop in terms of entrepreneurial survival and income, as well as for growth-oriented outcomes like job creation, innovation, and expansion activities. All effects are economically relevant and statistically significant, even when controlling for a large set of covariates known to be important for entrepreneurial success.

Second, we see that the influence of motivation is particularly strong for the growth-oriented outcomes like expansion and innovation activities. Thus, start-up motives are even more important for predicting the potential for firm growth (Haltiwanger & Miranda, 2013). This is policy-relevant, as freshly ventured businesses start having an impact on the economy only when they begin to grow and to innovate, while the majority of business founders have no intention to grow their businesses (Hurst & Pugsley, 2011).

Third, we observe that it is important to relate the various start-up motives to different dimensions of firm performance. More specifically, having differentiated between three motivational categories, we show that higher opportunity motivation when starting the business is associated with more firm innovation and more expansion activities of the business, but lower entrepreneurial income. It is important to note that opportunity entrepreneurs seem to care less or seem to make compromises when it comes to the earnings from their entrepreneurial activities. Higher career ambition is associated with higher survival rates of the firms, higher entrepreneurial income, and a larger probability of hiring employees in the firms, as well as with regional expansion of the firm. Thus, we reveal that these two motivational categories unfold mutually complementary influences on various dimensions of entrepreneurial performance. Given that these effects hold when controlling for a large set of covariates, this result points to the further insight that these two motivational categories do not just reflect human, working, or financial capital endowments of individuals, but unfold effects of their own.

Our analysis further indicates that the necessity motive exerts no significantly negative influence on the entrepreneurial performance once we control for the resource endowment of individuals. This allows for the interpretation that – in contrast to the other categories – the necessity motive mainly expresses a lower resource endowment of those individuals, for which we can control here through our extensive set of control variables as described in Section 3.3. These are relevant insights given the knowledge so far created by the dichotomous approaches like the push-pull or the GEM approach (Solymossy, 1997; Reynolds et al., 2002).

Fourth, we investigate how the previous labor market status relates to individual start-up motives. Earlier research assumes that the motivation of entrepreneurs coming from unemployment has an external locus of causality (Shane, 2009). We show that this is not necessarily the case as there is a considerable overlap between the two groups in terms of what motivates them to venture a business. Given this overlap in motives, we further reveal that start-up motives indicating an internal locus of causality unfold the same positive influence on firm performance in both groups. Therefore, our observations clarify why the previous employment status is not a helpful proxy for motivation and why it is necessary to disentangle the motivation for starting a business from the information on how the previous job was left. This has policy implications when public policy measures concentrate on individuals who start out of unemployment.

Last, but not least, we, fifth, investigate the underlying mechanisms mediating the link between start-up motives and firm performance (Brinckmann et al., 2010). Having used information on plans for some of the performance measures shows that there is also a significantly positive relationship between start-up motives and the plans to grow and expand the business, or to innovate. Thus, one potential mechanism that may explain the motivation-performance relationship is through making plans for such outcomes that are captured in these performance measures.

Our findings have several research and policy implications. The results allow for the interpretation that the motivation of individuals to start an entrepreneurial career affect how entrepreneurs manage their businesses after the venturing of their firms. Thus, as the policy debate on entrepreneurship increasingly centers on firm growth, our results show that such firm growth or the willingness of individuals to be innovative is partly rooted in their specific motivation to transition into entrepreneurship. Moreover, our analysis reveals that innovative and, at the same time, growing firms are more likely to be developed if the entrepreneurs of these firms are simultaneously motivated by both opportunity and career ambition. In that sense, we contribute to the understanding of which individual variables affect later business outcomes. Thus, motivation is another central variable in addition to the well-established influence of other variables and factors that we control for in our empirical analysis. Given that there is also a broad discussion on how growth motives in the later entrepreneurial process influence firm growth (see inter alia Brockner et al., 2008; Delmar & Wiklund, 2008), we might further interpret our results in the direction that start-up motives that are based on an internal locus of causality might constitute an important antecedent of subsequent growth motives. This must be accounted for when developing policy measures.

There are further implications of our findings for both research and policy with respect to start-ups out of unemployment, on the one hand, and with respect to non-financial support measures for entrepreneurs, on the other. Regarding start-ups out of unemployment, past literature on push and pull motives recommends that individuals out of unemployment should not be encouraged to move into entrepreneurship because they are more strongly pushed into this employment form (Shane, 2009). Our findings suggest that it depends on the motivation of this specific group as not all of them are solely motivated by necessity motives. Clearly, start-ups out of unemployment might be able to contribute to economic growth if they score high on the motivational index. At the same time, we observe that not all individuals coming out of non-unemployment are pulled into entrepreneurship.

Since these newly ventured businesses may have a positive effect on economic development, it is important to analyze in future research whether start-up motives unfold influence over even longer periods of time than the first 3.5 years that we examine. The study of Van Stel et al. (2018) certainly points in this direction. To this end, more empirical research is needed on how the reasons underlying the decision to engage in entrepreneurial activities affect later business performance.

6 Conclusion

We show that start-up motives significantly matter for firm performance and reveal particularly strong effects for outcome measures like expansion or innovation activities that signal firm growth. Moreover, the two motivational categories opportunity and career ambition unfold mutually complementary influence on various dimensions of entrepreneurial performance. These findings have important policy implications as our analysis shows that start-up motives are an important antecedent of firm growth. When designing policy measures intending to support start-ups, it is worth accounting for the motivation that drive individuals in their decision to become an entrepreneur irrespective of whether these individuals started out of unemployment or non-unemployment.

Notes

Independence involves the willingness to be free of any external control and to become one’s own boss. Self-realization, recognition, and financial incentives reflect motivational factors pertaining to the aspiration of gaining approval for entrepreneurial activities, whether through the realization of goals (Fischer et al., 1993), through other people (Nelson, 1968), or through financial success (Birley & Westhead, 1994). See also Shane et al. (2003) and Locke and Baum (2007) for details on these motivations in the entrepreneurial process.

In this context, we point to Jayawarna et al. (2011), who developed seven different motivational factors (based on 21 items) observed among entrepreneurs. Without further empirical analysis, they speculate about the influence of these factors on firm growth and hypothesize that individuals who they label as reluctant entrepreneurs would realize slower firm growth, while financially driven or achievement-oriented entrepreneurs should realize higher firm growth.

Given this proposed link between labor market status and motivation, we present research comparing the firm performance of previously unemployed with previously employed individuals, even when these individuals were labeled as opportunity or necessity entrepreneurs.

As we are discussing various start-up motives in this contribution, we understand the term entrepreneur in a broad sense. This includes entrepreneurs as innovative drivers of technological change as well as self-employed individuals with simple business ideas.

This is also suggested by Ajzen’s (1991) theory of planned behavior.

This concept is different from the concept of locus of control, which refers to the beliefs of individuals regarding to what extent certain outcomes result from forces within (internal) or outside (external) of themselves (Rotter, 1966).

This expectation corresponds to research on inventors who are supposed to be intrinsically motivated where extrinsic rewards may even crowd out their intrinsic motivation, see also Deci et al. (1999).

Note that administrative data shows that, for this time period, virtually all business founders out of unemployment received the start-up subsidy. Individuals were entitled to access the program if they fulfilled certain preconditions. Thus, we are confident that our sample data does not contain any positive bias among all previously unemployed entrepreneurs.

See Caliendo et al. (2016) for detailed evaluation results.

We show in our robustness analysis in Section 4.3 that the results do not depend on this weighting procedure.

The question was: “Now, let us talk about your start-up motives. Please rate for each of the following start-up motives to what degree it applied to you? Please answer on the basis of a scale ranging from 1 “does not apply at all” to 7 “applies entirely.”

This classification is confirmed by factor analysis, which results in three factors, where “idea” and “niche” load onto factor 1 (with 0.63 and 0.61); “no regular employment,” “discriminated,” and “recommended by others” load onto factor 2 (with 0.35, 0.34, and 0.35); while “money” and “boss” load onto factor 3 (with 0.41 and 0.43). We use these factors in our robustness analysis in Section 4.3.

See also Block et al. (2014), who propose that trademarks may also be used as proxy for innovation activities.

Full estimations results for all other outcome variables are available upon request from the authors.

See also Caliendo et al. (2022) for a detailed analysis of variables influencing the hiring decision.

Detailed results of the factor analysis are available on request from the authors.

The interviews were conducted between November 2010 (16%) and January 2011 (36%), most in December 2010 (48%). The survey institute tried to contact the business founders as soon as possible after their registration; the average time-lag was 7 weeks.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Alvarez, S., & Barney, J. (2007). Discovery and creation: Alternative theories of entrepreneurial action. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1, 11–26.

Andersson, P., & Wadensjö, E (2007). Do the unemployed become successful entrepreneurs? A comparison between the unemployed, inactive and wage-earners. International Journal of Manpower, 28, 604–626.

Astebro, T., & Chen, J. (2014). The entrepreneurial earnings puzzle: Mismeasurement or real? Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 88–105.

Baron, R., & Kenny, D. (1986). Moderator-mediator variables distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Baum, J., & Locke, E. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 587–598.

Baum, J., & Smith, K. (2001). A multi-dimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292–303.

Benz, M., & Frey, B. (2008). Being independent is a great thing: Subjective evaluations of self-employment and hierarchy. Economica, 75, 362–383.

Birley, S., & Westhead, P. (1994). A taxonomy of business start-up reasons and their impact on firm growth and size. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 7–31.

Blanchflower, D., & Oswald, A. (1998). What makes an entrepreneur? Journal of Labor Economics, 16, 26–60.

Block, J., De Vries, G., Schumann, J., & Sandner, P. (2014). Trademarks and venture capital valuation. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(4), 525–542.

Block, J., Kohn, K., Miller, D., & Ullrich, K. (2015). Necessity entrepreneurship and competitive strategy. Small Business Economics, 44(1), 37–54.

Block, J., & Sandner, P. (2009). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs and their duration in self-employment: Evidence from german micro data. Journal of Industry Competition and Trade, 9, 117–137.

Block, J., & Wagner, M. (2010). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in Germany: Characteristics and earnings differentials. Schmalenbach Business Review, 62, 154–174.

Bosma, N., van Praag, M., Thurik, R., & de Wit, G. (2004). The value of human and social capital investments for the business performance of start-ups. Small Business Economics, 23, 227–236.

Brinckmann, J., Grichnik, D., & Kapsa, D. (2010). Should entrepreneurs plan or just storm the castle? A meta-analysis on contextual factors impacting the business planning–performance relationship in small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(1), 24–40.

Brockner, J., Higgins, E.T., & Low, M.B. (2004). Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 203–220.

Brody, N., & Ehrlichman, H. (1998). Personality psychology. NJ, Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F., & Kritikos, A.S. (2022). Personality characteristics and the decision to hire. Industrial and Corporate Change, 31, 736–761.

Caliendo, M., Hogenacker, J., Künn, S., & Wießner, F (2015). Subsidized start-ups out of unemployment: A comparison to regular business start-ups. Small Business Economics, 45 (1), 165–190.

Caliendo, M., & Kritikos, A.S. (2010). Start-ups by the unemployed: Characteristics, survival and direct employment effects. Small Business Economics, 35(1), 71–92.

Caliendo, M., Künn, S., & Weissenberger, M. (2016). Personality traits and the evaluation of start-up subsidies. European Economic Review, 86, 87–108.

Caliendo, M., Göthner, M., & Weißenberger, M (2020a). Entrepreneurial persistence beyond survival: Measurement and determinants. Journal of Small Business Management, 58, 617–647.

Caliendo, M., Künn, S, & Weissenberger, M. (2020b). Catching up or lagging behind? The lo ng-term business and innovation potential of subsidized start-ups out of unemployment. Research Policy, 49(10), 104053.

Carrasco, R. (1999). Transitions to and from self-employment in Spain: An empirical analysis. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 61(3), 315–341.

Carsrud, A., & Brännback, M. (2011). Entrepreneurial motivations: What do we still need to know? Journal of Small Business Management, 49(1), 9–26.

Carter, N., Gartner, W., Shaver, K., & Gatewood, E. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18, 13–39.

Chrisman, J.J., McMullan, E., & Hall, J. (2005). The influence of guided preparation on the long-term performance of new venture. Journal of Business Venturing, 20, 769–791.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2000). Pushed out or pulled in? Self-employment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Labour Economics, 7, 603–628.

Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

de Vries, N., Liebregts, W., & van Stel, A. (2020). Explaining entrepreneurial performance of solo self-employed from a motivational perspective. Small Business Economics, 55, 447–460.

Deci, E., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668.

Delmar, F., & Wiklund, J. (2008). The effect of small business managers’ growth motivation on firm growth: A longitudinal study. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 32(3), 437–457.

Dencker, J., Bacq, S., Gruber, M., & Haas, M. (2021). Reconceptualizing necessity entrepreneurship: A contexualized framework of entrepreneurial processes under the condition of basic needs. Academy of Management Review, vol. 46(1).

Douglas, E.J. (2013). Reconstructing entrepreneurial intentions to identify predisposition for growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 633–651.

Dunkelberg, W., Moore, C., Scott, J., & Stull, W. (2013). Do entrepreneurial goals matter? Resource allocation in new owner-managed firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 225–240.