Abstract

Compulsive sexual behavior is a phenomenon characterized by a persistent failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges, resulting in repetitive sexual behavior that causes marked distress or impairment in personal, familial, social, educational, or occupational areas of functioning. Despite its major impact on mental health and quality of life, little is known about its internal structure and whether this phenomenon differs across genders, age groups, and risk status. By considering a large online sample (n = 3186; 68.3% males), ranging from 14 to 64 years old, compulsive sexual behavior was explored by means of network analysis. State-of-the-art analytical techniques were adopted to investigate the pattern of association among the different elements of compulsive sexual behavior, identify possible communities of nodes, pinpoint the most central nodes, and detect differences between males and females, among different age groups, as well as between individuals at low and high risk of developing a full-blown disorder. The analyses revealed that the network was characterized by three communities, namely Consequence, Preoccupation, and Perceived Dyscontrol, and that the most central node was related to (perceived) impulse dyscontrol. No substantial differences were found between males and females and across age. Failing to meet one’s own commitments and responsibilities was more central in individuals at high risk of developing a full-blown disorder than in those at low risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It has long been acknowledged that excessive sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors may affect people’s lives and eventually impair their well-being and psychosocial functioning (Krafft-Ebing, 1907). A variety of terms, such as hypersexuality, sexual addiction, and out-of-control sexual behavior, have been used to describe this set of symptoms (Sassover & Weinstein, 2022). In 2019, compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CBSD) was officially recognized as a new diagnostic construct and included among the impulse-control disorders of the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11; World Health Organization [WHO], 2019).

CSBD is defined as a persistent failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges, resulting in repetitive sexual behavior that causes marked distress or impairment in personal, familial, social, educational, or occupational areas of functioning, for a period of at least six months. CBSD is excluded if the distress derives from moral judgements and disapproval about sexuality (WHO, 2019). Given its core elements, compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) consists of both observable features, namely frequent sexual activities and sex-related consequences, and subjective features, namely feelings that one’s sexual behaviors and thoughts are uncontrollable and the associated distress (Walton et al., 2017).

Individuals with CSB typically engage in non-paraphilic activities, namely masturbation, pornography, sex with anonymous partners, but they do so to the extent that their behavior substantially interferes with personal, interpersonal, and vocational occupations (Slavin, et al., 2020). CSB has been associated with a variety of negative consequences, such as sexually transmitted diseases, unwanted pregnancies, social isolation, reduced self-esteem, financial problems, and legal violations (Walton et al., 2017). Moreover, individuals with CSB often show comorbid disorders, namely mood disorders, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, personality disorders, and obsessive–compulsive disorders (Carpenter et al., 2013; Kafka & Hennen, 2002; Kingston & Firestone, 2008).

Although CSBD has been included in the ICD-11 as a new category (WHO, 2019), mounting evidence indicates that this phenomenon is organized dimensionally, along a continuum with increasing levels of sexual frequency and preoccupations (Graham et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2011). In other words, individual differences in CSB are better conceptualized as a matter of degree, ranging from low or negligible up to high and clinically relevant levels of frequent sexual behaviors and cognitions. Therefore, the current state of knowledge warrants research on nonclinical samples.

Several characteristics moderate the intensity of CSB. For instance, a recent systematic review reported that gender may play a significant role, with men typically reporting higher levels of CSB as compared to women (Kürbitz & Briken, 2021). Moreover, women are more worried than men about negative consequences of their sexual behavior, such as unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases, physical injuries, and pain (Öberg et al., 2017). However, at least two features are worth considering. First, women may not report less frequent sexual intercourses than men (Långström & Hanson, 2006) and gender differences in reports of CSB may be due to stigma associated with women's sexual behavior (Baćak & Štulhofer, 2011; Lewczuk et al., 2017). Second, differences in CSB across gender are blurred when considering sexual orientation (Bőthe et al., 2018).

Less investigated is the relationship between CSB and age. Preliminary evidence shows that the age of onset of excessive sexuality in males is approximately 15 years old, with large variability (7–46 years) and median duration of 12 years (Kafka & Hennen, 2003). Both positive and negative correlations between age and CSB have been reported, although the magnitude of the effect is small (r <|.2|) (Dodge et al., 2004; Klein et al., 2015; Semple et al., 2006). This inconsistency in findings may be due to the fact that the majority of the studies recruited individuals within a limited age range, such as adolescents (Efrati & Gola, 2018), adults (Walton & Bhullar, 2018), or with comorbid conditions, such as elderly individuals with cognitive impairment (Wallace & Safer, 2009).

Despite the increasing interest in CSB, several characteristics of this phenomenon remain unexplored. First, it is largely unknown how the different features of CSB are specifically related to one another. Only one study has so far investigated the interaction of different elements of CSB (i.e., hypersexuality). By relying on network analysis (see below), Werner et al. (2018) revealed the central role of psychological distress due to one’s sexuality and sexuality-related negative feelings across both genders. Furthermore, sexual urge had a prominent role in men, whereas lack of control over sexual feelings had a prominent role in women. Hence, it is important to shed light on the specific network across the different features of CSB, as this could improve our understanding of the phenomenon (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013).

Second, several studies showed that men typically report higher mean levels of CSB than women do (Kürbitz & Briken, 2021, but see Långström & Hanson, 2006). However, it is unknown if the underlying network of associations among its elements also differ across genders. In other words, CSB could be structured in a similar fashion in men and women, but to a different degree of intensity. Werner and et al.’s (2018) study provided preliminary information about the associations among hypersexuality, negative consequences, and related sexual behaviors. They reported no significant difference across genders. Hence, further evidence on this topic is warranted.

Third, no strong evidence is currently available on CSB across different age groups. It is of importance to clarify if the structure of the associations among its elements changes across age or it persists in a stable fashion from adolescence up to late adulthood. On the one hand, time-limited periods of excessive sexual behavior have been reported, suggesting that CSB may be episodic and temporally unstable under certain circumstances (Kafka, 2010). On the other hand, there is evidence that CSB usually lasts for long periods of time (Kafka & Hennen, 2003). In sum, differences in CSB across different age groups are still unknown.

Fourth, given its dimensional nature (Graham et al., 2016; Walters et al., 2011), it is important to clarify if the structure of CBS differs between individuals at low or high risk to develop a full-blown disorder (i.e., CSBD). While the role of specific risk factors has been established (Grant Weinandy et al., 2022), it is unknown if the internal structure of CSB is different between individuals who show clinically relevant levels of CSB symptoms (i.e., high-risk) and those who do not report any substantial complaint (i.e., low-risk).

This study aims to reach four major goals. By capitalizing on previous literature (Werner et al., 2018), the first two objectives are to expand our understanding of CSB and to further explore gender differences. The second two objectives are novel: exploring how the network of CSB symptoms changes across different age groups and between individuals at low and high risk for developing CSBD.

To meet these goals, I adopted an innovative approach to understand psychopathology, namely network analysis (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). This new perspective posits that clinical conditions (i.e., CSB) emerge from interactions among different types of thoughts, beliefs, and emotions, instead of being generated by an underlying factor (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). In other words, while traditional approaches (i.e., factorial analysis) focus on which elements are more likely to cluster, network analysis explores how the different elements are related to one another (Bansal et al., 2020). By doing so, network analysis can show (1) all the links and their overall pattern (i.e., edges and network structure), (2) which elements are most strongly connected to all the other elements (i.e., node strength), (3) whether specific clusters of elements function in a similar way (i.e., communities), and (4) whether the network differs across groups (i.e., inter-network difference).

Two additional aspects of network analysis are worth commenting on. First, using estimating networks on cross-sectional data is contentious and open to various interpretations (Rodebaugh et al., 2018). In line with previous studies (Bernstein et al., 2019; Bottesi et al., 2020; Marchetti, 2019), in this study network analysis at the group level is intended to highlight the causal skeleton of CSB, where the edges between every pair of nodes represent links that can be directed, bidirectional, or influenced by unmodeled variables (Dalege et al., 2017). Subsequent idiographic (network) studies can then clarify the exact nature of these links at the individual level (Fisher et al., 2017). Therefore, the primary aim of this study is generating specific hypotheses about possible relationships among elements of CSB, which will be tested in subsequent experimental and longitudinal studies. Second, although network analysis is often applied to investigate specific psychological constructs (i.e., CSB), its domain is limited by the elements included in the analysis (i.e., questionnaire items) (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013). Despite this important limitation, recent meta-analytic evidence suggests that central nodes and robust edges are likely to emerge, even when different measures for the same construct are considered (Malgaroli et al., 2021).

In sum, I investigated the network structure of CSB in a large online sample of over 3000 individuals from adolescence to late adulthood, in order to reach the four goals of this study, namely (1) to establish the network structure of CSB, (2) to investigate if males and females differ with regard to the network structure, (3) to ascertain if the network structure changes across different age groups, and (4) to test if the network of CSB is different between individuals at low and high risk to develop a full-blown CSBD. To this end, I explored CSB as measured with the Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), which is one of the most frequently used self-report questionnaires for this phenomenon (Montgomery-Graham, 2017).

Method

Participants

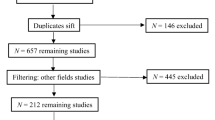

Out of the initial sample of 3376 individuals, 191 individuals were excluded due to missing data, data entry errors, or inappropriate age-range. The final sample consisted of 3186 individuals (age 30.6 ± 10.9 years old; range = 14–64 years old; 68.3% males). Importantly, the sample included individuals from several age groups, namely adolescents (n = 128; age 14–17 years old; 60.9% males), young adults (n = 1195; age 18–25 years old; 59.00% males), adults (n = 1253; age 26–40 years old; 70.9% males), and older adults (n = 610; age 41–64 years old; 82.6% males). The data are publicly available from the Open-Source Psychometric Project (https://openpsychometrics.org/).Footnote 1

Measures

Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS; Kalichman & Rompa, 1995). The SCS is one of the most frequently used measures for assessing sexual compulsivity and it consists of 10 items, for which responses are given on 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1 “Not at all like me”—4 “Very much like me”) (Hook et al., 2010). SCS has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in terms of internal consistency (range Cronbach’s α = 0.77–0.90) and temporal stability over 2 weeks (r = 0.95; Kalichman & Rompa, 1995) and 3 months (r = 0.64, Kalichman et al., 1994). Several studies showed that SCS has strong convergent validity, in that SCS correlates with numbers of sexual partners, lower self-esteem, lower sexual control, and sexually transmitted diseases (Kalichman, 2020). SCS showed excellent concurrent validity with other measures of CSBD, such as the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (r = 0.82; Reid et al., 2011) and the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (r = 0.87; Scanavino et al., 2016). Moreover, a systematic review of the literature showed that SCS has good construct validity, content validity, validity generalization, and internal consistency, as well as adequate norms (Montgomery-Graham, 2017). Previous research suggested a value ≥ 24 as a cutoff score for individuals at risk to develop a full-blown disorder (Montgomery-Graham, 2017, but see Ventuneac et al., 2015).

Statistical Analysis

Initially, means and standard deviations of all the SCS items, in the whole sample and split by gender and age groups, were investigated. Further, I evaluated the informativeness of each item by means of standard deviation (Mullarkey et al., 2019) and explored the degree of redundancy among all the pairs of items (Jones, 2018).

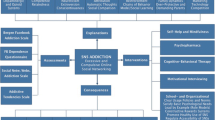

Then, in accordance with the current guidelines (Epskamp & Fried, 2018), an EBIC graphical LASSO network model with all the SCS items was estimated, in order to obtain a sparse network consisting of non-spurious associations. Blue edges indicate positive associations, while red edges indicate negative ones, with saturation and thickness signifying stronger link between nodes.

In the context of network analysis, groups of nodes that are tightly linked and function in a rather similar way are defined communities (Fortunato, 2010). Although network communities and latent factors may be mathematically equivalent (Chandrasekaran et al., 2010), their interpretation differs substantially. On the one hand, latent factor analysis aims to identify the unobservable entity (i.e., CSBD) that generates the observable indicators (i.e., compulsive sexual behaviors, thoughts, etc.). On the other hand, the network approach contends that CSBD is generated by causal interactions among compulsive sexual behaviors, feelings and consequences (i.e., indicators). No latent, unobservable factor is needed (Costantini & Perugini, 2018; Dalege et al., 2016). In this study, community analysis was performed by means of the walktrap algorithm, which is largely used in psychological research (Golino & Epskamp, 2017).

Global network structure was explored with two indices, namely strength and predictability (Epskamp et al., 2018; Haslbeck & Waldorp, 2018; Jones, 2018). For each node, strength refers to the sum of the absolute weights of the edge (Valente, 2012), while predictability quantifies the amount of explained variance for a certain node by all the nodes connected to it (Hanslbeck & Waldorp, 2018).

Network accuracy and stability were investigated with a twofold approach, namely (1) centrality stability and bootstrapped difference test for the centrality index; (2) edge accuracy and bootstrapped difference test for edges (Epskamp et al., 2018). Strength indices and edges were considered stable if the correlation stability coefficient (i.e., CS-coefficient) was above 0.25, but preferentially above 0.5. The accuracy of the edges was investigated with 1000-bootstrap 95% nonparametric confidence intervals (CIs), with narrower CIs indicating that the estimated parameter is more reliable and trustworthy. Intra-network comparisons of strength indices and edges similarly relied on bootstrap CIs, with the difference being statistically significant if the CIs did not include zero.

In order to approximate how well the network structure could generalize to new data in independent studies, I integrated network estimation with tenfold cross-validation (James et al., 2013). Specifically, the association between every pair of nodes was quantified as “deviance explained” (R2D), namely the ratio of Kullback–Leibler divergence between fitted and null models (Cameron & Windmeijer, 1997). Importantly, R2D approximates the traditional R2 and ranges from 0 to 1. Then, I iteratively estimated the pattern of associations on a subset of the whole sample (i.e., 9 out 10 folds; train subset) and subsequently tested it on data previously unseen by the model (i.e., 1 out of 10 folds; test subset). The procedure was repeated 10 times. Predictive deviance explained (predictive R2D) was estimated on the test subsets and indicates the fraction of uncertainty that the model is expected to account for in new data (Beevers et al., 2019; Marchetti et al., 2018). This analytical process was conducted by means of the R package “beset” (Shumake, 2018). Finally, partialization and regularization were applied on the matrix of predictive R2D values, in order to compute an EBIC graphical LASSO network model. By doing so, I could build a cross-validated predictive network, which approximates to what extent the initial estimated network could generalize to new data and replicate in independent studies.

As for the inter-network comparison, I followed the statistical procedure outlined by van Borkulo et al. (2022) in order to investigate the network features between genders, age groups, and risk status. By relying on 1000 permuted data sets, each pair of networks (i.e., males vs. females; adolescents vs. adults, etc.; low-risk vs. high-risk) was tested with respect to the global connectivity difference (i.e., absolute sum of all the edges) and the network structure difference (i.e., maximum absolute element-wise difference). Depending on the latter, differences at the level of edges were also tested. Finally, strength differences between networks were evaluated.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Total score, means, standard deviations, and Pearson’s correlations for the whole sample are reported in Table S1. Total score, means, and standard deviations split by genders, age groups, and risk status are shown in Tables S2, S3, and S4, respectively.

Network Estimation, Community Detection, Network Inference, Stability, and Cross-Validation in the Whole Sample

The preliminary analysis revealed that no item was poorly informative (i.e. 2.5 SD below the mean level of informativeness; Mullarkey et al., 2019). Moreover, no item was detected as redundant with any other item (i.e., less than 25% statistically different correlations; Jones, 2018).

The network of cognitions and behaviors related to CSB across the whole sample is shown in Fig. 1, and several points are noteworthy. First, the analysis revealed a specific pattern of moderate interconnectedness among the different SCS variables (sparsity = 0.156), which was further qualified by the community analysis. The walktrap algorithm detected three communities, the first of which indicated the observable psychosocial consequences of CSB (“Consequence”), such as “My desires to have sex have disrupted my daily life” (item 3) and “I sometimes fail to meet my commitments and responsibilities because of my sexual behaviors” (item 4). The second community captured the subjective difficulties to control and manage sexual impulses (“Perceived Dyscontrol”), such as “I have to struggle to control my sexual thoughts and behavior” (item 8) and “I feel that sexual thoughts and feelings are stronger than I am” (item 7). Finally, a third community consisted of only two items, namely “I find myself thinking about sex while at work” (item 6) and “It has been difficult for me to find sex partners who desire having sex as much as I want to” (item 10). This last community captured variables indicating the contexts where CSB may occur in a problematic manner (“Preoccupation”).

The analysis of the edges revealed specific patterns of association. Within the Consequence community, the experience of strong sexual appetite as an obstacle to relationships (item 1) was associated with problems in one’s life due to sexual thoughts and behaviors (item 2), which were in turn linked with disrupted daily life (item 3). Eventually, experiencing interfered daily routine (item 3) was associated with failing to meet commitments and responsibilities (item 4). Within the Preoccupation community, thinking of sex while at work (item 6) was associated with the difficulties in finding a sexual partner who shows the same level of sexual desire (item 10). Interestingly, the Perceived Dyscontrol community mainly consisted of spending an excessive amount of time thinking about sex (item 9), which was associated with struggling to control sexual thoughts and behaviors (item 8) as well as feelings being overpowered by sexual impulses (item 7). The latter two items were also linked with the feeling of losing control due to sexual tension (item 5).

Importantly, the estimation of the edges was carried out in a very precise and stable way (Figure S1; CS-coefficient = 0.75), with the majority of the edges being statistically different from one another (Figure S2). The analysis of the network structure across the whole sample showed that four nodes had the highest centrality (Fig. 2), namely struggling to control sexual impulses and experiencing overwhelming sexual feelings (items 8 and 7; Perceived Dyscontrol community), going through a disrupted daily life and reporting problems in personal life (items 3 and 2; Consequence community). These four items were statistically stronger than the rest of the items (Figure S3) and the strength indices were estimated in a very stable way (CS-coefficients = 0.75). Moreover, the estimated network and the cross-validated predictive network were highly similar (Figure S4) and were associated with almost identical strength (Figure S5; rs = 0.94). Hence, stability analysis and cross-validation suggest that the network is trustworthy and likely to generalize to new data.

The predictability analysis revealed that, on average, 48% of each item variance could be accounted for by the surrounding items, with the predictability indices ranging from 30 and 64%. Specifically, the Consequence and Perceived Dyscontrol communities could be explained to a degree of 53% and 52% of variance, respectively, while only 32% of the variance of the Preoccupation community could be accounted for.

Network and Mean Level Differences by Gender

The networks of CSB in males and females (Figure S6) were highly correlated in terms of edges (rs = 0.84) and strength indices (rs = 0.92; Figure S7). The two networks were computed in a reliable and stable way (all CS-coefficients = 0.75; Figure S8). Similar to the network for the whole sample, struggling to control sexual thoughts and behaviors (item 8) was the most central item (Figure S5). Community analysis in the female group produced results similar to those of the whole sample, with disruptive sexual urges (item 1) and intrusive thoughts at work (item 6) clustering with the Preoccupation and Perceived Dyscontrol communities. In males, only the Consequence and the Perceived Dyscontrol communities were detected. Moreover, there was no difference in global connectivity (difference = 0.31, p = 0.09), while the network structure differed across gender (difference = 0.14, p < 0.02). Specifically, the edges between items 3 and 1, and items 1 and 6, were statistically stronger in males than in females. The edges between items 3 and 6, items 1 and 8, items 6 and 9, and items 1 and 10 were statistically stronger in females than in males. While all the differences were negligible (difference < 0.10), only the link between reporting sexual urges interfering with personal relationships (item 1) and having difficulty in finding a matching partners (item 10) was of small magnitude (difference = 0.11). At the level of node strength, item 1 was statistically stronger in females than in males (difference strength = 0.19, p < 0.017). At the level of mean levels, females reported higher levels of feeling of losing control due to sexual desire (difference = 0.23, p < 0.001), although the magnitude of the effect was small (Cohen’s d = 0.21; Table S2).

Network and Mean Level Differences by Age

The network of CSB was computed across the different age groups (Fig. 3). All the networks could be estimated in a reliable and stable way (Figure S9; CS-coefficient range = 0.44–0.75).

The networks across the four age groups were moderately to highly correlated, in terms of edges (range rs = 0.67–85) and strength indices (range rs = 0.64–96; Fig. 2) (Table 1). In a similar fashion across the age groups, struggling to control sexual thoughts and behaviors (item 8) and experiencing a disrupted daily life (item 3) were the most central item. Moreover, no difference at the level of global connectivity (all p = 1), network structure (range p = 0.72–1), or strength difference (range p = 0.18–1) was detected. Similarly, when age was entered as a moderator within the network (moderated network analysis; Haslbeck et al., 2021), no significant interactions were detected (Figure S10).

When adolescents and young adults were considered, nodes were clustered in almost an identical fashion. The community analysis revealed only two clusters, namely Consequence and Perceived Dyscontrol. In adults and older adults, a similar pattern emerged, although the items representing the Preoccupation community (items 6 and 10), along with the feeling of losing control because of the intense sexual desire (item 5) in older adults, were clustered separately.

When investigating differences at the mean level across the four samples, four items were statistically different, namely items 1, 2, 5, and 10 (Table S3). However, effect sizes indicated small to negligible magnitude (η2 < 0.012). Finally, age was associated with any of the SCS items to a negligible degree (r =|.08|).

Network and Mean Level Differences by Risk Status

By applying the standard cutoff for assessing the risk status (i.e., SCS score ≥ 24), 51.2% of the whole sample was classified at low risk and 48.8% at high risk. It is mentioning that sample splitting based on median or specific cutoff scores has been adopted in previous network analysis studies (McNally et al., 2014; Semino et al., 2017; Siew et al., 2019). The network of CSB was estimated in individuals at low or high risk (Figure S11), in a reliable and stable manner (Figure S12; CS-coefficient = 0.75 for both networks). Although the two networks were highly correlated in terms of edges (rs = 0.85) and strength centrality (rs = 0.83), they showed partially different communities. In particular, while the network in individuals at high risk was identical to that of the whole sample, individuals at low risk showed only two communities, namely Preoccupation and Perceived Dyscontrol.

Moreover, the two networks did not differ with respect to global connectivity (p = 0.69) and network structure (p = 0.14). However, the item reflecting the experience of failing to meet the commitments due to the interference of sexual behaviors (item 4) was statistically more central in individuals at high risk than in those at low risk to develop CBSD (p < 0.001; Figure S13). Finally, all the item means were largely higher in individuals at high risk than in those at low risk (Table S4).

Discussion

CSB is characterized by a persistent failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges, resulting in repetitive sexual behavior that causes marked distress or psychosocial impairment (WHO, 2019). Despite the increasing interest in this phenomenon, it has so far remained how the different components of CSB are specifically related to one another and if the pattern is stable across gender, age groups, and risk status. To bridge this gap, I performed a network analysis on a large sample, in order to shed light on the internal structure of this phenomenon.

Community analysis of the CSB network revealed the presence of three clusters, namely Consequences, Preoccupation, and Perceived Dyscontrol. The first community captured the negative outcomes of CSB on everyday life, relationships, and commitments, which have been extensively documented in the scientific literature. For instance, individuals with CSB often report serious problems due to their sexual activities, among which dropping out of school, losing jobs, unwanted financial losses, social isolation, marital adversities, and mental health distress (Koós et al., 2021). The second community consisted of only two items and referred to concerns that are frequent in the context of CSB, such as having sexual thoughts in workplace (Reid & Wolley, 2006) and the difficulty of finding a partner with similar levels of sexual drive (Hentsch-Cowles & Brock, 2013). Finally, the last community included items on perceived dyscontrol of sexual impulses and urges, which are later discussed in detail.

An almost identical clusterization of the items was found in a recent study that relied on exploratory factor analysis (EFA; Kingston et al., 2018). In my study, item 3 was included in the Consequence community, while in Kingston et al.’s (2018) study it saturated on the Perceived Dyscontrol factor. This result, however, is not unexpected, given that in the EFA study item 3 cross-loaded on both the Consequences and the Dyscontrol factors. Moreover, a partially similar structure was found for the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Reid et al., 2011), where the subscales Control and Consequences closely mirror the network communities Perceived Dyscontrol and Consequences. Hence, previous literature confirms the trustworthiness of the community analysis and strongly indicates that the higher-level structure of the Sexual Compulsivity Scale is characterized by three major areas.

When examining the network pattern of associations, specific nodes and edges are worth commenting on. Within the Consequence community, items 2 and 3 emerged as central nodes, indicating that in the context of CSB negative consequences are likely to be influential. In particular, sex-related psychosocial problems often take the form of failing to meet important commitments in the work place (i.e., edge between items 3 and 4) or experiencing disruptiveness in personal relationships (i.e., edge between items 2 and 1). In a recent study on over 5000 individuals (Koós et al., 2021), these two domains showed different profiles, in that having work problems was markedly associated with experiencing overall negative consequences, while having relationship problems was positively correlated with subjectively reported control impairments.

Within the Preoccupation community, experiencing relationship problems was linked with difficulties in finding a sex partner who matches the same intensity of sexual desire (i.e., edge between items 1 and 10). Previous evidence showed that members of couples likely differ with regard to their level of CSB (Starks et al., 2013), with intensity of relational problems being associated with the number of sexual and casual sexual partners (Koós et al., 2021). Taken together, these findings suggest a pattern of social deterioration, characterized by frequent and potentially conflicting sexual relationships.

Furthermore, experiencing sexual thoughts while being at work (item 6) was associated with both excessively frequent sexual fantasies and being preoccupied to lose control (i.e., edges between items 6 and 9 and items 6 and 5). In keeping with this, intensity of sexual desire and sexual urge were found to be linked with having problems at the workplace (Werner et al., 2018). Moreover, sex-related disruptions in the professional domain may lead to severe negative consequences, such as occupational problems (i.e., being fired; Schultz et al., 2014) and feelings of guilt and shame (Reid, 2010).

Within the Perceived Dyscontrol community, the most central node was struggling to control one’s own sexual thoughts and behavior (item 8), which was also the strongest node of the whole network. This finding confirms previous empirical and theoretical work that conceives of CSB as an impulsive disorder, according to which failing to resist an impulse for sexual activity plays a crucial role (Barth & Kinder, 1987; WHO, 2019).

In this study, the CSB network was substantially similar in men and women, with only negligible-to-small differences. A previous network analysis studies on hypersexuality reported no significant differences between genders (Werner et al., 2018), and measurement invariance between men and women has often been reported across measures of hypersexuality and CSB (Bőthe et al., 2018; Koós et al., 2021). It is to note that the difficulty to find a partner with similar sexual desire was more central in women than in men. A possible explanation may be that it is harder for women with CSB to reveal their intense sexual desires to their partner, in that feelings of shame are particularly powerful and disempowering in this group (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2014; Ferree et al., 2012).

Importantly, the network of CSB elements was markedly stable when considering individuals between 14 and 64 years old. This is in line with evidence showing that specific features of human sexuality do not substantially change across the lifespan. For instance, CSB has been positively associated with “sexual excitation proneness” and negatively linked with “sexual inhibition due to possible threatening consequences” (Miner et al., 2016; Rettenberger et al., 2016). Both these features have been considered as stable traits that are largely genetically determined (Janssen & Bancroft, 2007). Moreover, theoretical work suggests that CSB could be better conceived as a personality organization, characterized by specific motivations and persistent maladaptiveness of sexual behavior, along with stability and long duration of these patterns (Montaldi, 2003). These pieces of evidence indicate that the CSB network might be already stably structured in adolescence and persist with virtually no change across different age groups. Last, in the adolescent and young adult samples two communities emerged, while in the adult and older samples three communities were detected. It is to note that both two- and three-factor structures for the SCS have been documented (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2013; Liao et al., 2015; Kingston et al., 2018).

Finally, individuals at high and low risk of developing full-blown CSBD were characterized by networks that were similar in terms of structure and global connectivity. Nevertheless, the node reflecting the experience of failing to meet commitments and responsibilities due to one’s sexual behavior (item 4) was statistically more central in at-risk individuals. This finding mirrors a recent cluster analysis study, where neglect (of which the SCS item 4 was the most representative, as expressed by the highest factorial loading) could strongly discriminate between individuals with and without CSBD (Castro-Calvo et al., 2020). Taken together, these pieces of evidence indicate that both magnitude and the specific role of negative consequences due to CSB ought to be considered in order to provide a comprehensive clinical assessment. Future studies should focus on evaluating if specific consequences, such as work-related, personal, health-related, or relationship-related, might have different impacts on mental well-being and psychosocial functioning (Koós et al., 2021).

Clinical Implications

Two main clinical implications can be derived. First, struggling to control one’s own sexual thoughts and behavior emerged as the most central node of the whole network. While the association between CSB and self-reported impulsivity is often reported (Bőthe et al., 2018; Carvalho et al., 2015), studies relying on behavioral measures of impulsivity provided mixed evidence, with both positive and null association being reported (Carvalho et al., 2021; Miner et al., 2016). Taken together, these findings may indicate that individuals with CSB do not necessarily show an impaired impulse control, but they may be characterized by maladaptive beliefs about the controllability of their sexual behavior (Pachankis et al., 2014). Hence, although equating node centrality to causality is currently debated (Dablander & Hinne, 2019), targeting personal beliefs that sexual behavior is completely out of control could represent a major focus for clinical interventions in individuals with CSB. Accordingly, clinical guidelines, case studies, and empirical work also suggest that building personal self-efficacy and restructuring self-justification cognitions may be an effective way in treating CSB and preventing future relapses (Dilley et al., 2007; Shepherd, 2010; Weiss, 2004).

Second, failing to meet commitments and responsibilities was statistically more central in individuals at high risk than in those at low risk. In other words, in vulnerable individuals CSB-related consequences were not only more negative (i.e., mean), but they also likely played a different role in the network (i.e., centrality). It is possible to speculate that negative consequences may function as important stressors, which lead to negative mood that, in turn, is dealt with by means of compulsive sexual behaviors (Dhuffar et al., 2015). Hence, preventing major negative consequences could represent an effective way to prevent the full-blown disorder (Lew-Starowicz et al., 2020). Moreover, reporting negative consequences due to hypersexuality was the strongest predictor of experiencing the need for professional help in a large, online sample of over 58,000 individuals (van Tuijl et al., 2020). Hence, a comprehensive evaluation of negative consequences due to CSB is definitely advisable, for both treatment and prevention reasons.

Limitations

Several limitations should be taken into account. First, CSB as described by ICD-11 is a complex phenomenon and it consists of several features, which were not all captured by SCS (e.g., persistence of the excessive sexual behavior despite the absence of satisfaction). While future studies may complement my results with CBSD-specific measures (i.e., Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale-19; Bőthe et al., 2020), it is to note the SCS is still one the most frequently used measures for this phenomenon and investigating the structure of SCS is worthwhile. Moreover, a recent meta-analysis reported that it is possible to detect central nodes and robust edges in psychopathology, despite relying on different measures for the same construct (Malgaroli et al., 2021). Second, data were cross-sectional in nature and this prevented from directly estimating the temporal dynamics of CSB within the single individuals and across the different age groups. Future studies should consider relying on experience sampling studies or performing long-term longitudinal studies, which will allow to capture individual-based dynamics and track the developmental trajectory of CSB. Third, in this study only a limited sample of adolescents were included and this might have prevented the detection of small differences with respect to the other groups. Moreover, it was not possible to perform any network estimation on the elderly group, due to insufficient sample. Future studies should aim for a larger recruitment of elderly and adolescents, including also children (Adelson et al., 2012). Despite this limitation, the networks showed good-to-excellent indices of reliability and trustworthiness. In the future, the estimated network should be replicated in a larger sample, using SCS along with other measures for CSB (Hook et al., 2010; Montgomery-Graham, 2017). Fourth, limited information is provided with respect to the sociodemographic characteristics and no information is offered about the cultural background of the participants. By consequence, the degree of representativeness of the sample is difficult to evaluate. Future studies should conduct a population-based, stratified sample recruitment procedure and include additional individual differences, among which sexual orientation and psychiatric assessment. On the other hand, integrating network analysis with cross-validation led to the estimation of a cross-validated predictive network that was markedly similar to that estimated on current data. This indicates that the present results are not biased by overfitting and, in turn, are likely to generalize to future, independent studies. Moreover, performing secondary analysis on open-access data sets is a highly ethical practice, in that, among other benefits, it maximizes the value of public investment in data collection and reduces the burden on respondents (Kievit et al., 2022). Fifth, data collection was performed in 2012. In the future, researchers may want to replicate these results on more recent data and explore whether different sociocultural conditions associated with the passing of time have an impact on the structure of CSB.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shed light on the structure of CSB, as measured with the Sexual Compulsivity Scale, and revealed that impulse dyscontrol could be a major focus of clinical evaluation and perhaps a locus for clinical interventions. Moreover, the network of association among the CSB elements is not likely to be different across different age groups or between males and females. Finally, although no significant structural or connectivity differences were found between individuals at low and high risks, failing to meet one’s commitments and responsibilities was more central in individuals at high risk than in those who are at low risk. This element could be of importance for both preventive and treatment purposes.

Notes

The data set was uploaded on July 16, 2012, and it was retrieved on November 1, 2021. The participants provided their answer spontaneously and anonymously. At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were informed that their answer could be used for research purposes. Out of the total sample of individuals who provided their answers, only those who indicated that their results were accurate and suitable for research (79%) were disseminated.

References

Adelson, S., Bell, R., Graff, A., Goldenberg, D., Haase, E., Downey, J. I., & Friedman, R. C. (2012). Toward a definition of “hypersexuality” in children and adolescents. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40(3), 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.481

Baćak a, V., & Štulhofer, A. (2011). Masturbation among sexually active young women in Croatia: Associations with religiosity and pornography use. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2011.611220

Ballester-Arnal, R., Gómez-Martínez, S., Llario, M. D. G., & Salmerón-Sánchez, P. (2013). Sexual compulsivity scale: adaptation and validation in the spanish population. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 39(6), 526–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2012.665816

Bansal, P. S., Goh, P. K., Lee, C. A., & Martel, M. M. (2020). Conceptualizing callous-unemotional traits in preschool through confirmatory factor and network analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(4), 539–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-019-00611-9

Barth, R. J., & Kinder, B. N. (1987). The mislabeling of sexual impulsivity. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 13(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926238708403875

Beevers, C. G., Mullarkey, M. C., Dainer-Best, J., Stewart, R. A., Labrada, J., Allen, J. J., McGeary, J. E., & Shumake, J. (2019). Association between negative cognitive bias and depression: A symptom-level approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(3), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000405

Bernstein, E. E., Heeren, A., & McNally, R. J. (2019). Reexamining trait rumination as a system of repetitive negative thoughts: A network analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 63, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2018.12.005

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

Bőthe, B., Bartók, R., Tóth-Király, I., Reid, R. C., Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Orosz, G. (2018). Hypersexuality, gender, and sexual orientation: A large-scale psychometric survey study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2265–2276.

Bőthe, B., Potenza, M. N., Griffiths, M. D., Kraus, S. W., Klein, V., Fuss, J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). The development of the Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder Scale (CSBD-19): An ICD-11 based screening measure across three languages. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 247–258.

Bottesi, G., Marchetti, I., Sica, C., & Ghisi, M. (2020). What is the internal structure of intolerance of uncertainty? A network analysis approach. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 75, 102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102293

Cameron, A. C., & Windmeijer, F. A. (1997). An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. Journal of Econometrics, 77(2), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(96)01818-0

Carpenter, B. N., Reid, R. C., Garos, S., & Najavits, L. M. (2013). Personality disorder comorbidity in treatment-seeking men with hypersexual disorder. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 20(1–2), 79–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2013.772873

Carvalho, J., Rosa, P. J., & Štulhofer, A. (2021). Exploring hypersexuality pathways from eye movements: The role of (sexual) impulsivity. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 18(9), 1607–1614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.06.018

Carvalho, J., Štulhofer, A., Vieira, A. L., & Jurin, T. (2015). Hypersexuality and high sexual desire: Exploring the structure of problematic sexuality. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(6), 1356–1367. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12865

Castro-Calvo, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., Giménez-García, C., Gil-Juliá, B., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2020). Occurrence and clinical characteristics of Compulsive Sexual Behavior Disorder (CSBD): A cluster analysis in two independent community samples. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(2), 446–468. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00025

Chandrasekaran, V., Parrilo, P. A., & Willsky, A. S. (2010). Latent variable graphical model selection via convex optimization. In 2010 48th Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton) (pp. 1610–1613). IEEE.

Costantini, G., & Perugini, M. (2018). A framework for testing causality in personality research. European Journal of Personality, 32(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2150

Dablander, F., & Hinne, M. (2019). Node centrality measures are a poor substitute for causal inference. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-43033-9

Dalege, J., Borsboom, D., Van Harreveld, F., Van den Berg, H., Conner, M., & Van der Maas, H. L. (2016). Toward a formalized account of attitudes: The Causal Attitude Network (CAN) model. Psychological Review, 123(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039802

Dalege, J., Borsboom, D., van Harreveld, F., & van der Maas, H. L. (2017). Network analysis on attitudes: A brief tutorial. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(5), 528–537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617709827

Dhuffar, M. K., & Griffiths, M. D. (2014). Understanding the role of shame and its consequences in female hypersexual behaviours: A pilot study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 3(4), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.3.2014.4.4

Dhuffar, M. K., Pontes, H. M., & Griffiths, M. D. (2015). The role of negative mood states and consequences of hypersexual behaviours in predicting hypersexuality among university students. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 4(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.030

Dilley, J. W., Woods, W. J., Loeb, L., Nelson, K., Sheon, N., Mullan, J., Adler, B., Chen, S., & McFarland, W. (2007). Brief cognitive counseling with HIV testing to reduce sexual risk among men who have sex with men: Results from a randomized controlled trial using paraprofessional counselors. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 44(5), 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/qai.0b013e318033ffbd

Dodge, B., Reece, M., Cole, S. L., & Sandfort, T. G. (2004). Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. Journal of Sex Research, 41(4), 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552241

Efrati, Y., & Gola, M. (2018). Understanding and predicting profiles of compulsive sexual behavior among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 1004–1014. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.100

Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

Ferree, M., Hudson, L., Katehakis, A., McDaniel, K., & Valenti-Anderson, A. (2012). Etiology of female sex and love addiction: A biopsychosocial perspective. In M. C. Ferree (Ed.), Making advances: A comprehensive guide for treating female sex and love addicts (pp. 44–66). SASH.

Fisher, A. J., Reeves, J. W., Lawyer, G., Medaglia, J. D., & Rubel, J. A. (2017). Exploring the idiographic dynamics of mood and anxiety via network analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(8), 1044–1056. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000311

Fortunato, S. (2010). Community detection in graphs. Physics Reports-Review Section of Physics Letters, 486(3–5), 75–174. https://doi.org/10.11606/d.45.2021.tde-24022021-164949

Golino, H. F., & Epskamp, S. (2017). Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. PLoS ONE, 12(6), e0174035. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174035

Graham, F. J., Walters, G. D., Harris, D. A., & Knight, R. A. (2016). Is hypersexuality dimensional or categorical? Evidence from male and female college samples. Journal of Sex Research, 53(2), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.1003524

Grant Weinandy, J. T., Lee, B., Hoagland, K. C., Grubbs, J. B., & Bőthe, B. (2022). Anxiety and compulsive sexual behavior disorder: A systematic review. The Journal of Sex Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2066616

Haslbeck, J. M., Borsboom, D., & Waldorp, L. J. (2021). Moderated network models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 256–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1677207

Haslbeck, J., & Waldorp, L. J. (2018). How well do network models predict observations? On the importance of predictability in network models. Behavior Research Methods, 50(2), 853–861. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0910-x

Hentsch-Cowles, G., & Brock, L. J. (2013). A systemic review of the literature on the role of the partner of the sex addict, treatment models, and a call for research for systems theory model in treating the partner. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 20(4), 323–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2013.845864

Hook, J. N., Hook, J. P., Davis, D. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Penberthy, J. K. (2010). Measuring sexual addiction and compulsivity: A critical review of instruments. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 36(3), 227–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926231003719673

James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2013). An introduction to statistical learning: With applications in R. Springer.

Janssen, E., & Bancroft, J. (2007). The dual control model: The role of sexual inhibition and excitation in sexual arousal and behavior. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 197–222). Indiana University Press.

Jones, P. J. (2018). Networktools: Assorted tools for identifying important nodes in networks. R package version 1.2.0.

Kafka, M. P. (2010). Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39(2), 377–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7

Kafka, M. P., & Hennen, J. (2002). A DSM-IV Axis I comorbidity study of males (n= 120) with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 14(4), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320201400405

Kafka, M. P., & Hennen, J. (2003). Hypersexual desire in males: Are males with paraphilias different from males with paraphilia-related disorders? Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 15(4), 307–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320301500407

Kalichman, S. C. (2020). Sexual compulsivity scale. In R. R. Milhausen, J. K. Sakaluk, T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, & W. L. Yarber (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (pp. 260–261). Routledge.

Kalichman, S. C., Johnson, J. R., Adair, V., Rompa, D., Multhauf, K., & Kelley, J. A. (1994). Sexual sensation seeking: Scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62(3), 385–397. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1

Kalichman, S. C., & Rompa, D. (1995). Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 586–601. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16

Kievit, R. A., McCormick, E. M., Fuhrmann, D., Deserno, M. K., & Orben, A. (2022). Using large, publicly available data sets to study adolescent development: Opportunities and challenges. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 303–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.10.003

Kingston, D. A., & Firestone, P. (2008). Problematic hypersexuality: A review of conceptualization and diagnosis. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 15(4), 284–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160802289249

Kingston, D. A., Walters, G. D., Olver, M. E., Levaque, E., Sawatsky, M., & Lalumière, M. L. (2018). Understanding the latent structure of hypersexuality: A taxometric investigation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 2207–2221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1273-9

Klein, V., Schmidt, A. F., Turner, D., & Briken, P. (2015). Are sex drive and hypersexuality associated with pedophilic interest and child sexual abuse in a male community sample? PloS One, 10(7), e0129730. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129730

Koós, M., Bőthe, B., Orosz, G., Potenza, M. N., Reid, R. C., & Demetrovics, Z. (2021). The negative consequences of hypersexuality: Revisiting the factor structure of the Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale and its correlates in a large, non-clinical sample. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 13, 100321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100321

Krafft-Ebing, R. (1907). Psychopathia sexualis. F. Enke.

Kürbitz, L. I., & Briken, P. (2021). Is compulsive sexual behavior different in women compared to men? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(15), 3205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153205

Långström, N., & Hanson, R. K. (2006). High rates of sexual behavior in the general population: Correlates and predictors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-8993-y

Lewczuk, K., Szmyd, J., Skorko, M., & Gola, M. (2017). Treatment seeking for problematic pornography use among women. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.063

Lew-Starowicz, M., Lewczuk, K., Nowakowska, I., Kraus, S., & Gola, M. (2020). Compulsive sexual behavior and dysregulation of emotion. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 8(2), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.10.003

Liao, W., Lau, J. T., Tsui, H. Y., Gu, J., & Wang, Z. (2015). Relationship between sexual compulsivity and sexual risk behaviors among Chinese sexually active males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(3), 791–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0317-z

Malgaroli, M., Calderon, A., & Bonanno, G. A. (2021). Networks of major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 85, 102000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102000

Marchetti, I. (2019). Hopelessness: A network analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 43(3), 611–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9981-y

Marchetti, I., Shumake, J., Grahek, I., & Koster, E. H. (2018). Temperamental factors in remitted depression: The role of effortful control and attentional mechanisms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.064

McNally, R. J., Robinaugh, D. J., Wu, G. W. Y., Wang, L., Deserno, M. K., & Borsboom, D. (2014). Mental disorders as causal systems. Clinical Psychological Science, 3(6), 836–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614553230

Miner, M. H., Romine, R. S., Raymond, N., Janssen, E., MacDonald, A., III., & Coleman, E. (2016). Understanding the personality and behavioral mechanisms defining hypersexuality in men who have sex with men. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(9), 1323–1331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.06.015

Montaldi, D. F. (2003). Understanding hypersexuality with an Axis II model. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 14(4), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1300/j056v14n04_01

Montgomery-Graham, S. (2017). Conceptualization and assessment of hypersexual disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 5(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2016.11.001

Mullarkey, M. C., Marchetti, I., & Beevers, C. G. (2019). Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 48(4), 656–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1437735

Öberg, K. G., Hallberg, J., Kaldo, V., Dhejne, C., & Arver, S. (2017). Hypersexual disorder according to the hypersexual disorder screening inventory in help-seeking Swedish men and women with self-identified hypersexual behavior. Sexual Medicine, 5(4), e229–e236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2017.08.001

Pachankis, J. E., Rendina, H. J., Ventuneac, A., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2014). The role of maladaptive cognitions in hypersexuality among highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(4), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0261-y

Reid, R. C. (2010). Differentiating emotions in a sample of men in treatment for hypersexual behavior. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 10(2), 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332561003769369

Reid, R. C., Garos, S., & Carpenter, B. N. (2011). Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory in an outpatient sample of men. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 18(1), 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2011.555709

Reid, R. C., & Woolley, S. R. (2006). Using emotionally focused therapy for couples to resolve attachment ruptures created by hypersexual behavior. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 13(2–3), 219–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720160600870786

Rettenberger, M., Klein, V., & Briken, P. (2016). The relationship between hypersexual behavior, sexual excitation, sexual inhibition, and personality traits. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(1), 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0399-7

Rodebaugh, T. L., Tonge, N. A., Piccirillo, M. L., Fried, E., Horenstein, A., Morrison, A. S., Goldin, P., Gross, J. J., Lim, M. H., Fernandez, K. C., & Blanco, C. (2018). Does centrality in a cross-sectional network suggest intervention targets for social anxiety disorder? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(10), 831–844. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000336

Sassover, E., & Weinstein, A. (2022). Should compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) be considered as a behavioral addiction? A debate paper presenting the opposing view. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00055

Scanavino, M. D. T., Ventuneac, A., Rendina, H. J., Abdo, C. H., Tavares, H., Amaral, M. L. S. D., Messina, B., Reis, S. C. D., Martins, J. P., Gordon, M. C., Vieira, J. C., & Parsons, J. T. (2016). Sexual Compulsivity Scale, Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory, and Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory: Translation, adaptation, and validation for use in Brazil. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0356-5

Schultz, K., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Penberthy, J. K., & Reid, R. C. (2014). Nonparaphilic hypersexual behavior and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 40(6), 477–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2013.772551

Semino, L., Marksteiner, J., Brauchle, G., & Danay, E. (2017). Networks of depression and cognition in elderly psychiatric patients. GeroPsych, 30(3), 89–96. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000170

Semple, S. J., Zians, J., Grant, I., & Patterson, T. L. (2006). Sexual compulsivity in a sample of HIV-positive methamphetamine-using gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 10(5), 587–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-006-9127-1

Shepherd, L. (2010). Cognitive behavior therapy for sexually addictive behavior. Clinical Case Studies, 9(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534650109348582

Shumake, J. (2018). beset: Best subset predictive modeling. R package version 0.0.0.9409. https://github.com/jashu/beset

Siew, C. S. Q., McCartney, M. J., & Vitevitch, M. S. (2019). Using network science to understand statistics anxiety among college students. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 5(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000133

Slavin, M. N., Blycker, G. R., Potenza, M. N., Bőthe, B., Demetrovics, Z., & Kraus, S. W. (2020). Gender-related differences in associations between sexual abuse and hypersexuality. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(10), 2029–2038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.07.008

Starks, T. J., Grov, C., & Parsons, J. T. (2013). Sexual compulsivity and interpersonal functioning: Sexual relationship quality and sexual health in gay relationships. Health Psychology, 32(10), 1047–1056. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030648

Valente, T. W. (2012). Network interventions. Science, 337(6090), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195301014.003.0011

van Borkulo, C. D., Boschloo, L., Kossakowski, J., Tio, P., Schoevers, R. A., Borsboom, D., & Waldorp, L. J. (2022). Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychological Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000476

van Tuijl, P., Tamminga, A., Meerkerk, G. J., Verboon, P., Leontjevas, R., & van Lankveld, J. (2020). Three diagnoses for problematic hypersexuality; which criteria predict help-seeking behavior? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6907. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186907

Ventuneac, A., Rendina, H. J., Grov, C., Mustanski, B., & Parsons, J. T. (2015). An item response theory analysis of the sexual compulsivity scale and its correspondence with the hypersexual disorder screening inventory among a sample of highly sexually active gay and bisexual men. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12783

Wallace, M., & Safer, M. (2009). Hypersexuality among cognitively impaired older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 30(4), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.09.001

Walters, G. D., Knight, R. A., & Långström, N. (2011). Is hypersexuality dimensional? Evidence for the DSM-5 from general population and clinical samples. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(6), 1309–1321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9719-8

Walton, M. T., & Bhullar, N. (2018). Hypersexuality, higher rates of intercourse, masturbation, sexual fantasy, and early sexual interest relate to higher sexual excitation/arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2177–2183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1230-7

Walton, M. T., Cantor, J. M., Bhullar, N., & Lykins, A. D. (2017). Hypersexuality: A critical review and introduction to the “Sexhavior cycle.” Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(8), 2231–2251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0991-8

Weiss, R. (2004). Treating sex addiction. In R. H. Coombs (Ed.), Handbook of addictive disorders: A practical guide to diagnosis and treatment (pp. 233–274). John Wiley.

Werner, M., Štulhofer, A., Waldorp, L., & Jurin, T. (2018). A network approach to hypersexuality: Insights and clinical implications. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.01.009

World Health Organization (WHO). (2019). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th ed.). https://icd.who.int/

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to Marko Simonović for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trieste within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The author has not disclosed any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The Ethics Committee of the University of Trieste (Italy) approved this secondary analysis study.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marchetti, I. The Structure of Compulsive Sexual Behavior: A Network Analysis Study. Arch Sex Behav 52, 1271–1284 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02549-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-023-02549-y