Abstract

In the contemporary 24/7 working society, the separation of work and private life is increasingly turning into an unrealizable ideal. Ruminating about work outside the work context lets work spill over into private lives and affects the dynamics of workers’ private relationships. Although negative work rumination was linked to couples’ reduced relationship satisfaction, little is known about the mechanism of action and the impact of positive work rumination. Drawing on the load theory of selective attention, we hypothesize that both negative and positive work rumination occupy attentional resources and thus reduce workers' attention to the partner on the same day. Lower levels of attention to the partner, in turn, should relate to lower levels of both partners’relationship satisfaction. However, sharing the work-related thoughts with the partner might support the resolution of the work issue the worker is ruminating about, which releases attentional resources and thus buffers the negative association between rumination and attention to the partner. We conducted a daily diary study and the findings based on 579 daily dyadic observations from 42 dual‐earner couples support the proposed cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism and the buffer mechanism of thought-sharing. We conclude that negative and positive work rumination takes up scarce attentional resources and thus jeopardizes relationship quality. However, sharing thoughts with one's partner seems to be a useful strategy for couples to maintain or even increase their relationship satisfaction in the light of work rumination.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Today's working society is characterized by processes of acceleration (Rosa, 2011), flexibilization (Eurofound & the International Labour Office, 2017), and intensification (Korunka & Kubicek, 2017)—a situation that imposes increased demands on workers, making them more vulnerable to ruminate about their work outside of working hours (Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015). Especially workers living in dual–earner living arrangements are challenged in balancing work–related demands—and thoughts—with private ones to maintain a functional and fulfilling relationship (e.g., Debrot et al., 2018), a central feature of wellbeing (Ryff & Singer, 2008).

While there is a large body of studies showing detrimental effects of negative work reflection and beneficial effects of positive work reflection on workers’ work engagement, personal thriving, and life satisfaction (Weigelt et al., 2019), we lack knowledge on the impact of rumination about work outside working hours on a couple’s relationship. This is astonishing insofar as the time off-work during which rumination happens is also the only time of the day romantic partners can interact face-to-face. Work and personal lives are known to compete over scarce time resources, which can lead to conflict (Greenhouse & Beutell, 1985). It seems therefore inevitable that ruminative thoughts about work outside working hours will in some way compete with the partner for the worker’s resources. With this couples study we want to fill this knowledge gap and to clarify the impact of rumination on a couple’s daily relationship satisfaction by highlighting the effect of rumination on attention. Thereby, we make two important contributions to the literature.

First, we introduce a new cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism and extend previous spillover-crossover literature which has been predominantly oriented at how supportive or undermining exchanges affect couples’ relationship satisfaction (e.g., Bakker & Demerouti, 2013; Debrot et al., 2018). Drawing on load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004), we propose that thoughts about work outside of working hours occupy scarce attentional resources and thus lower workers’ attention to their partners on that day. Thereby, we argue that negative and positive thoughts about work outside working hours occupy attentional resources the worker might need to direct at the partner. Although negative rumination is known to have unfavorable consequences and positive rumination is known to have favorable consequences for workers (e.g., Jimenez et al., 2022; Weigelt et al., 2019), with regard to interpersonal relationships, positive rumination should be seen as critically as negative rumination. As attention is a crucial precondition for couples’ interactions with each other which, in turn, determine the quality of their relationship (Rogers & May, 2003), we assume that attention is positively associated with both partners’ relationship satisfaction on that day.

Second, we introduce a measure that helps couples to cope with the hypothesized detrimental consequences of rumination for their relationship quality. We suggest that sharing the work-related thoughts with the partner buffers the detrimental impact of negative as well as positive rumination on attention to the partner. As ruminative thoughts need to be dissolved in order to disappear (Martin & Tesser, 1996), dyadic coping (such as discussing the work issue one is ruminating about with the partner) should speed up the problem solving processes (Bodenmann, 1997; Lin et al., 2016) and thus free attentional resources one can direct to the partner (Lavie et al., 2004). We conducted a daily diary study to test the hypothesized daily mechanisms in the lives of dual–earner couples during their after-work hours.

2 Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1 Rumination About Work as a Crucial Factor in the Spillover-Crossover Process

Ruminative thoughts about work outside working hours are “a class of conscious thoughts that revolve around a common instrumental theme and that recur in the absence of immediate environmental demands requiring the thoughts” (Martin & Tesser, 1996; p. 7). Thoughts about work outside working hours can be negatively or positively valanced and primarily reflect an attempt to resolve an experienced negative or positive discrepancy between what one has expected and what one has actually experienced (Martin & Tesser, 1996). Negative work rumination refers to the “preoccupation with and repetitive thoughts focused on negative work experiences” (Frone, 2015; p. 5) and evolves after demanding, unpleasant or stressful work situations (Frone, 2015; Volmer et al., 2012). Especially after experiencing strain, individuals keep thinking about the stressor causing the strain, and these “perseverative cognitions” prolong the affective stress response (Brosschot et al., 2005). For example, negative rumination may occur after experiences associated with professional failure and arguments with co-workers. On the other side, positive work rumination involves thinking about positive work experiences and follows work events the worker experienced as pleasant, for example because they were associated with successful task accomplishments or friendly work relationships (Frone, 2015; Meier et al., 2016).

The concept of work rumination is overlapping with negative and positive work reflection which refers to thinking about the negative/positive aspects of one’s job (Casper et al., 2019). However, opposite to work rumination, work reflection is not repetitive (Jimenez et al., 2022) and primarily performed by people with high self-regulation and goal internalization (Kirkegaard Thomsen et al., 2011). The literature further distinguishes between work rumination from other phenomena that involve thinking about work outside of working hours, but which are not the focus of this study. These phenomena are problem-solving pondering (i.e., thinking about work-related challenges with the aim to find a solution, yet these thoughts are neither experienced as explicitly negative nor as positive; Cropley & Zijlstra, 2011), psychological detachment (i.e., not thinking about work at all in order to stop the influence of work stressors and thus to enable the recovery from work-related strain; Sonnentag & Fritz, 2015), and affective (negative) rumination (i.e., having recurrent thoughts about work, but this negative rumination is contaminated with negative affect such as feelings of strain;Cropley & Zijlstra, 2011; Jimenez et al., 2022). In this study, we solely focus on negative and positive work rumination as a cognitive phenomenon that is clearly valanced, repetitive, and not necessarily related to positive and negative feelings.

Rumination about work outside working hours can be seen as a psychological process in which work spills over into workers’ private lives by influencing their thoughts and consequently their experiences and behaviors outside their working hours (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). Correspondingly, Frone (2015) linked unpleasant work experiences to negative rumination about work outside working hours and pleasant work experiences to positive rumination about work. In turn, negative thinking about work outside working hours is negatively associated with workers’ wellbeing, such as increased feelings of anxiety (Kirkegaard Thomsen et al., 2011; Michl et al., 2013), exhaustion (Donahue et al., 2012; Weigelt et al., 2019), and depressive mood (Segerstrom et al., 2006), as well as with lower job satisfaction and work engagement (Jimenez et al., 2022). In contrast, prior studies emphasized that positive thinking about work outside working hours benefits workers’ wellbeing, for example in terms of higher levels of vitality (Weigelt et al., 2019), serenity (Meier et al., 2016), relaxation (Fritz & Sonnentag, 2006), and job satisfaction (Jimenez et al., 2022), as well as lower levels of exhaustion (Clauss et al., 2018), depressive mood (Meier et al., 2016), burnout, and physical health complaints (Jimenez et al., 2022).

Due to their interactions during their private time together, however, experiences made at work do not only influence workers’ experiences and behaviors outside working hours—they also cross over and affect their partners’ experiences and behaviors (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). Dyadic research on psychological detachment from work showed that workers’ daily psychological detachment is beneficial for their relationship satisfaction (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2018). The authors argued that workers’ relationship satisfaction increased because not thinking about work increases the chance of couples’ positive-affectionate interactions with each other which, in turn, increase workers’ positive affect and thus also their relationship satisfaction. Debrot et al. (2018) further linked workers’ psychological detachment to higher relationship satisfaction of the workers and their partners, but the mediation via the increased positive-affectionate interactions of couples remained nonsignificant. Examining interpersonal coping with occupational stress, King and DeLongis (2014) indicated that thinking about work outside working hours (without any valence of these thoughts) is a deleterious coping response and relates to higher marital tension as experienced by the workers but not by the partners. Finally, Green et al. (2011) focused on affective (negative) rumination and showed that the more workers affectively ruminate about work at home the more their partners perceive an interference of their work with their shared private life.

So far, spillover-crossover research on this issue is scarce but points towards a negative relationship between thinking about work outside of working hours and the quality of a couple’s relationship. However, we still lack information on the mechanism linking work-related thoughts and a couple’s relationship satisfaction. Ezzedeen and Swiercz (2007) pointed out that ruminating about work makes it more difficult for workers to participate in private activities due to a “cognitive preoccupation” (p. 979) with work. Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al. (2013) argued that workers’ negative work residuals (including negative mood, exhaustion, and rumination) are lowering their “psychological availability” for their partners, which they defined as “ability and motivation to direct psychological resources at the partner,” (p. 54). In a cross-sectional study, the authors showed that the more workers ruminate about work outside their working hours, the less psychologically available they are for their spouses. Psychological availability, in turn, was related to higher marital anger and withdrawal as well as to lower marital positivity as perceived by the spouses. We conducted this study in order to pick up directly where they left off and to further clarify the cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism following work rumination theoretically and empirically.

2.2 Rumination and Attention to the Partner

The load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004) states that human working memory can only handle a certain perceptual load at any one time and thus must select what information will be processed—and thus paid attention to—and what will be ignored. Attention is the cognitive process that allocates the working memory’s limited cognitive processing resources toward selectively chosen information associated with the current focus of attention (Lavie et al., 2004). The current focus of attention is the stimulus of which most information is processed at the moment as compared to other stimuli (Lavie & Tsal, 1994; Macdonald & Lavie, 2011). Consequently, rumination about work should make the work issue the focus of attention and simultaneously causes the workers to ignore information that is not congruent to the attentional work task.

As positive work experiences also induce work-related cognitions (Martin & Tesser, 1996), we emphasize that negative as well as positive thoughts about work may intrude workers’ working memory and become the center of attention outside working hours. However, the notion that positive rumination induces cognitions that occupy working memory resources has received far less attention than negative rumination. So far, especially experiences of strain and anxiety were described to induce cognitions that compete with limited working memory resources which is expressed in a lack of concentration (Cropley et al., 2016; Sneddon et al., 2013), an impaired declarative memory (Kirschbaum et al., 1996), a reduced cognitive performance (Sliwinski et al., 2006). There are scarce empirical findings showing that positive life events produce intrusive cognitions (Berntsen, 1996; Brewin, 1999; Klein & Boals, 2001).

Attention determines perception processes in the sense that information relevant to the stimulus in the focus of attention is processed before information irrelevant to the stimulus in focus (Lavie et al., 2004). This happens no matter whether the information on the stimulus in focus are stemming from internal sources such as own thoughts or from external ones such as another person (Lavie, 2010). Consequently, even if they are physically together with their partner in the same room and the partner wants to discuss an important matter, ruminating workers may be mentally preoccupied and thus not able to take full notice of their partners at the moment. Correspondingly, Mellings and Alden (2000) showed that the more a person’s attentional focus was on their own thoughts, the less they were able to process information about the partner. Cognitive research linked strain-induced negative thoughts to mind wandering (e.g., Boals & Banks, 2020; Klein & Boals, 2001) which is defined as “a state of decoupled attention because, instead of processing information from the external environment, our attention is directed toward our own private thoughts and feelings” which “represents a fundamental breakdown in the individual’s ability to attend (and therefore integrate) information from the external environment” (Smallwood et al., 2007; p. 230). With regard to work, Cardenas et al. (2004) showed that the higher the experienced work overload (i.e., having too much to do at work), the longer workers indicate to be mentally and behaviorally distracted by work issues during family time. Moreover, as already stated, Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al. (2013) revealed that thinking about work outside working hours is associated with a lower ability and motivation to direct psychological resources at the partner.

In summary, we hypothesize that negative and positive rumination about work have the same effect on workers’ attention: When their working memory is occupied with their thoughts about work, workers will have fewer attentional resources left for the partner. In other words, the higher the extent of workers’ rumination about work, the lower their attention to the partner on that day. Conversely, the lesser the extent of workers’ rumination on a given day, the higher their (potential to pay) attention to the partner on that day.

Hypothesis 1

The higher the workers' (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on a given day, the lower their attention to their partner on that day.

2.3 Attention to the Partner and Relationship Satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction is an important indicator of subjective wellbeing (Diener, 2000) and life satisfaction (Ruvolo, 1998). Contrary to affective wellbeing indicators with a hedonic tone (Organ & Near, 1985), relationship satisfaction reflects the cognitive evaluation of own feelings and attraction toward one’s partner and romantic relationship (Rusbult & Buunk, 1993). It is one of the most researched variables in studies on dyadic processes (Falconier et al., 2015) and has been shown to fluctuate on a daily basis (e.g., Debrot et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2018).

It seems logical that absent-mindedness of a partner due to work issues potentially reduces the total interaction time of a couple on that day. Correspondingly, when work spills over and occupies a worker’s attention during their time with the partner, the partners may interact less with each other. This is a critical development because interactions with the partner are necessary for the formation of one’s satisfaction with the relationship (Rogers & May, 2003). Vice versa, the absence of interactions was associated with lower levels of workers’ relationship satisfaction (Tandler et al., 2020). We thus argue that decreased attention to the partner during their time together may decrease workers’ relationship satisfaction due to a lack of interactions. In other words, the higher the workers' attention to the partner, the higher their relationship satisfaction on that day. Moreover, as a logical conclusion, we postulate that workers’ attention to the partner mediates the relationship between their ruminative thoughts about work and their relationship satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2

The higher the workers' attention to the partner on a given day, the higher their relationship satisfaction on that day.

Hypothesis 3

The higher the workers' (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on a given day, the lower their relationship satisfaction on that day, and this relationship is mediated via lower levels of the workers’ attention to the partner.

Workers’ decreased attention to the partner during their time together potentially may also decrease their partners’ relationship satisfaction which might be due to decreased interactions or due to a lack of workers’ responsiveness to the partner. First, as already stated, interactions with the partner are the basis for the formation of relationship satisfaction (Rogers & May, 2003), and the absence of interactions as reported by one partner was also associated with lower levels of the other partner’s relationship satisfaction (Johnson et al., 2018). Second, perceived partner responsiveness sustains intimacy in relationships. That is, partners who feel understood, validated, accepted, and cared for by the other perceive greater psychological closeness (Laurenceau et al., 2005). Vice versa, when workers are mentally absent and not responsive to their partners, they demonstrate limited involvement in dyadic exchanges which detrimentally affects partners’ feelings of intimacy (Cowlishaw et al., 2010) and thus also their relationship satisfaction (van Steenbergen et al., 2014). Consequently, we argue that workers’ attention to the partner relates positively to their partners’ relationship satisfaction and also mediates the relationship between workers’ ruminative thoughts about work and their partners’ relationship satisfaction.

Hypothesis 4

The higher the workers' attention to the partner on a given day, the higher their partners’ relationship satisfaction on that day.

Hypothesis 5

The higher the workers' (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on a given day, the lower their partners’ relationship satisfaction on that day, and this relationship is mediated via lower levels of the workers’ attention to the partner.

2.4 Sharing Work-Related Thoughts With the Partner as a Buffering Mechanism

“Talking about work during leisure time represents a behavioral pathway connecting work and home” (Tremmel et al., 2019; p. 248) which is known to help workers to shift their attention from work to their private life (Nippert-Eng, 1996). Talking about experiences made during the workday is a way couples share joy or cope with strain together by sharing appraisals (Falconier & Kuhn, 2019). By sharing with the partner, the negative or positive work issue is no longer “his” or “her”, but “their” issue (Lin et al., 2016). When both partners participate in the coping process and thus join forces in handling a problem-focused or emotion-focused issue relevant to the dyad, dyadic coping happens (Bodenmann, 1997). More specifically, talking with others about their thoughts should encourage elaboration because talking forces to order one’s thoughts in the mind and then to express them in whole sentences that contain all relevant details so that another person can comprehend the issue (Dunlosky & Hertzog, 2001). Focusing on concrete details such as what occurred where, when, and why has been shown to reduce rumination within depressive individuals (Watkins et al., 2012), and the deep encoding and storing of information in the long–term memory subsequently releases attentional resources in the working memory (Bartsch et al., 2018).

Negative as well as positive ruminative thoughts exist because of a discrepancy between what was expected and what was experienced, so rumination can be seen as an automatic psychological measure aiming to resolve this discrepancy in order to get cognitive closure (Martin & Tesser, 1996). Consequently, once the negative or positive work issue is understood and resolved, the workers stop ruminating. Following our argumentation on the postulated cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism based on load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004), the resolution of workers’ ruminative thoughts should release formerly occupied attentional resources which, in turn, can be directed toward the partner. Consequently, although rumination per se is a coping mechanism aiming to resolve a discrepancy and to get cognitive closure (Martin & Tesser, 1996), thought-sharing with the partner might speed up this process by means of dyadic coping. Taken together, we hypothesize that if workers talk with their partners about their work, the detrimental relationship between negative and positive work rumination and workers’ attention to the partner can be buffered.

Hypothesis 6

The negative relationship between workers’ (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on their attention to the partner on a given day will be attenuated by higher levels of workers’ sharing of work-related thoughts with the partner on that day.

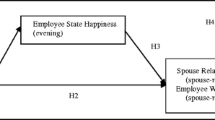

Finally, we integrate our hypotheses into an overall conceptual model outlining our proposed cognitive spillover–crossover mechanism and buffering mechanism (see Fig. 1) and formulate our last two hypotheses:

Overall conceptual model with the hypothesized cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism and the buffering mechanism (H6). Note: Dashed arrows symbolize assumed negative relationships, continuous arrows symbolize assumed positive relationships. The term “actor” refers to the worker and the term “partner” refers to the worker’s partner. The hypotheses referring to the indirect relationship between work rumination to actor’s (H3) and partner’s relationship satisfaction (H5) via actor’s attention to the partner as well as the moderated mediation hypotheses (H7 and H8) are not displayed

Hypothesis 7

Workers’ (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on a given day will indirectly relate to lower levels of the workers’ relationship satisfaction on that day via workers’ reduced attention to the partner; yet this mediation will be attenuated by higher levels of the workers’ sharing of work-related thoughts with the partner.

Hypothesis 8

Workers’ (a) negative and (b) positive rumination about work on a given day will indirectly relate to lower levels of the partners’ relationship satisfaction on that day via workers’ reduced attention to the partner; yet this mediation will be attenuated by higher levels of the workers’ sharing of work-related thoughts with the partner.

3 Method

Rumination, attention, and relationship satisfaction as key constructs of our hypothesized cognitive spillover-crossover model are each reflecting cognitive processes or evaluations that are subject to intrapersonal variation within short time intervals. Moreover, couples’ sharing of their work-related thoughts may vary from day to day. Consequently, we conducted a diary study to observe the proposed cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism and the buffering mechanism on a daily level. To avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012), we separated the daily measurement of work rumination from the measurement of the other variables. Moreover, to examine the hypothesized inter–individual crossover effects from workers to their partners, we analyzed our daily observations using an actor-partner interdependence model (Cook & Kenny, 2005; Kenny & Ledermann, 2010).

3.1 Procedure

Participating couples were recruited by psychology master’s degree students in the course of a class; students’ help with recruitment was voluntary and participants were not pressured to participate. First, participants completed an online questionnaire assessing background data and demographics. This was followed by the diary phase: In two weeks of their choice, participants (i.e., both partners of a dyad) were instructed to respond to two online questionnaires per work day, using a desktop computer or mobile device. All measurements were taken from each partner of each couple for a maximum of 10 days (Monday to Friday). Via e–mail and SMS, we sent a link to the Time 1 questionnaire at 7 pm, assessing negative and positive rumination about work, and to the Time 2 questionnaire at 9 pm each day, assessing attention to the partner, sharing work-related thoughts with the partner, and relationship satisfaction. The two daily surveys remained available throughout the evening. We chose 7 pm as the starting time for the Time 1 questionnaire based on the assumption that the majority of participants most likely had finished work for the day and thus already had some private time in which ruminative thoughts about work could develop. We further chose to send the Time 2 questionnaires at 9 pm in order to collect the data about couples’ interactions as late as possible in the day, so that participants had enough time to spend with their partners, yet early enough to catch them before bedtime.

3.2 Sample

In total, 60 heterosexual and cohabiting dual–earner couples in which both partners worked at least 20 h per week registered for study participation. To increase the data quality and thus the validity of our analyses, we restricted our data set based on two quality criteria. First, we only included data of participants that were provided in the correct chronological order (i.e., data from Time 1 followed by data from Time 2) and with at least 30 min passing between ending Time 1 and starting Time 2 questionnaires (the average time interval between filling in Time 1 and Time 2 questionnaire was 2.0 h with a standard deviation [SD] of 1.0 h). Secondly, we excluded daily rumination data if the participant reported that his or her last working hour was less than one hour before they started the Time 1 questionnaire (as we believed this would not provide enough time for them to develop ruminative thoughts about work).

Our final data file included 42 dual–earner couples (84 participants) and 579 dyadic observations on working days. All participants lived in Germany or Austria. The mean age was 36.9 years (SD = 11.6) and 78% of participants completed level 3 (or secondary) education. Most reported having no children (69.0%). Three participating couples were work–linked in the sense that both partners had the same occupation (1 couple), worked for the same organization (1 couple), or both (1 couple). Participants worked on average 40.9 h per week (SD = 11.2) and had spent an average of 7.3 years (SD = 8.6) in their current job; 15.7% (i.e., 13 participants) reported being self–employed. Drawing on the classification of occupations of the United Nations (International Labour Office, 2012), our sample comprised 43.9% professionals or associate professionals, 21.7% service and sales workers, 18.1% clerical support workers, 13.3% managers, and 2.4% craft or related trades workers.

3.3 Measures

All variables were measured via participants’ self–rating of questionnaires items in the form of personal statements. All items were provided in German. Where necessary, we translated the items from English to German. Participants responded to all items using 7–point Likert scales. The alpha reliabilities of the applied scales are displayed in Table 2.

3.3.1 Negative and Positive Rumination About Work

We assessed participants’ work–related ruminative thoughts outside working hours at Time 1 with the negative and positive work rumination scale (Frone, 2015) which comprises two subscales: Negative rumination about work as thinking about work experiences outside of working hours the participant appraised as negative and positive rumination about work as thinking about work experiences the participant appraised as positive. As two items of each subscale show a great resemblance with one another (In the negative rumination subscale, for example, these items are “How often do you think back to the bad things that happened at work even when you’re away from work?” and “How often do you keep thinking about the negative things that happened at work even when you’re away from work?”), we decided to drop one item of each subscale in order to keep the daily questionnaire short and thus the participants motivated in their study participation. More precisely, we dropped the items “How often do you keep thinking about the negative things that happened at work even when you’re away from work?” (negative rumination) and “How often do you keep thinking about the positive things that happened at work even when you’re away from work?” (positive rumination) and adapted the remaining three items for application in a daily–diary study. For negative rumination about work, a sample item reads “Today, outside working hours, I replayed negative work events in my mind” and for positive rumination about work, a sample item reads “Today, outside working hours, I remembered good things that happened at work”. Participants were asked to rate the items on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (to a very large extent). Alpha reliabilities ranged between 0.66 (study day 7) and 0.92 (day 9) for negative rumination and between 0.62 (day 1 and 2) and 0.87 (day 9) for positive rumination. The average person-level and day-level reliabilities are displayed in Table 2.

3.3.2 Attention to the Partner

We defined attention to the partner as the extent in which the participants paid attention to their partners during the evening hours after work they spent together. We measured the construct with three items based on Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al.'s (2013) psychological availability scale. The original scale measured workers’ “ability to direct psychological resources” and their “motivation to direct psychological resources” to the partner. As they did not capture attention, we did not use the items capturing motivation to direct psychological resources to the partner (e.g., “I was not in the mood to undertake anything with my partner”). The remaining three items were adapted for the purpose of this study. Participants were asked whether they either totally disagreed (1) or totally agreed (7) with these statements. Alpha reliabilities ranged between 0.83 (day 1 and 9) and 0.95 (day 7).

The first item used in our study read “When I was with my partner today,…my thoughts were not distracted but were completely with her/him” and was based on the item “When I was with my partner at the end of this workday… mentally, I was not ‘fully there’ for my partner” of the Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al. (2013) scale. We rephrased the item because we wanted to avoid inverted items because they considerably lower the reliability of short measurements (see e.g., Weijters & Baumgartner, 2012).

The second item of our study read “… I listened to her/him attentively” which basically corresponded to item “… I was well able to tell how my partner was doing” of Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al. (2013). We rephrased the item to make it more directly about the attention the worker paid to the partner. We did so because a person might not pay attention to the partner but might simultaneously be confident to know how the partner is doing due to social desirability.

Our third item read “…all my attention belonged to her/him” and was based on the item “… my thoughts were completely focused on my partner” of Danner-Vlaardingerbroek et al. (2013). We rephrased the item for two reasons. First, we wanted to avoid similarities with thoughts about work which are the predictors in our model. Second, we wanted to make sure to capture that the worker was attentive to the partner in the moment they interacted. Technically, having one in one’s thoughts can also mean that the worker was not together with the partner but thinking about him or her.

3.3.3 Sharing Work-Related Thoughts With the Partner

We measured sharing work-related thoughts with the partner with three items based on theoretical work about “oral role–referencing of work to nonwork” (Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, 2006) and empirical work about the sharing of daily events with the partner (Hicks & Diamond, 2008): “Today, I told my partner about my working day,” “Today, my partner and I talked about something about my job that kept me thinking,” and “Today, my partner and I talked about experiences I had at work.” Participants were asked to rate these statements on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (to a very large extent). As these items have not been tested before, we checked the indicators for their reliability and validity. The scale’s reliability proved to be satisfactory on both levels of analysis as they ranged between 0.85 (day 5) and 0.96 (day 8).

Looking at the confirmatory 5-factor analysis (see Table 1), the items loaded highly on one common latent factor (item 1 showed a standardized factor loading of 0.88, item 2 showed a loading of 0.75, and item 3 showed a loading of 0.88). Moreover, our data yielded positive correlations between thought-sharing and both forms of rumination as well with both partners’ relationship satisfaction on both levels of analysis (see Table 2). As thoughts about work provide material for conversations about work and the sharing of information of other life parts such as work potentially increases intimacy and thus relationship satisfaction, we argue that these correlations points toward the scale’s convergent validity.

3.3.4 Relationship Satisfaction

We measured relationship satisfaction with statements the participants either totally disagreed (1) or totally agreed (7) with. Three statements were taken from the quality marriage index (Norton, 1983) and adapted to the daily–diary design that reflected participants’ relationship-specific emotions and behaviors. We did so because, opposite to satisfaction indicators representing a cognitive evaluation of one’s life, “people's moods and emotions reflect on-line reactions to events happening to them” (Diener, 2000; p. 34). Consequently, relationship-specific emotions (e.g., our relationship makes me happy) should be more prone to temporal fluctuations as compared to cognitive evaluations of the relationship (e.g., our relationship is very stable). The items used in our study read “Today, the relationship with my partner made me very happy,” “Today, my the relationship with my partner felt very strong,” and “Today, my partner and I got along very well.” Alpha reliabilities ranged between 0.84 (day 1, 2, 8 and 10) and 0.93 (day 6).

3.3.5 Control Variable: Time Partners Spent Together

We controlled for the time the partners spent together outside their working hours on the respective study day and modeled it as an additional independent variable predicting attention to the partner. Therefore, we asked the participants in the Time 2 questionnaire with one item to indicate the total amount of hours they had spent together with their partner on this day during their waking hours. The time the two partners of a couple spend together is important as it is unlikely (and unnecessary) to pay attention to each other when they are asleep or involved in activities separately from each other.

3.4 Data Preparation

We prepared our data for the conduction of multilevel path modeling that simultaneously analyzes intraindividual (and in our case also interindividual) differences on the day-level nested within persons (see e.g., Zhang et al., 2009). Therefore, we first matched the Time 1 with Time 2 questionnaire data for each respective day and person into one multilevel data file. Consequently, we had a data set in which each participant had one row for each day he or she participated. In other words, as our sample comprised 42 heterosexual couples, our data set included 42 female and 42 male actors and as many partners. In this row, his or her data from Time 1 and Time 2 were linked, enabling us to examine the hypothesized intra–individual spillover effects from workers to workers (i.e., actor effects).

Secondly, for measuring bidirectional effects in interpersonal relationships, we further prepared our data set in terms of an actor-partner interdependence model (see e.g., Cook & Kenny, 2005; Kenny & Ledermann, 2010). This specifically allowed us to examine the hypothesized inter–individual crossover effects from workers to their partners (i.e., partner effects), simultaneous to the actor effects. For this purpose, we doubled the participants’ daily data in a way that, for every day he or she participated, every participant now had two entries: in one row the participant was an actor and in the other row he or she was a partner.

3.5 Construct Validity

To examine the distinctiveness of our measures (i.e., construct validity), we conducted multilevel confirmatory factor analyses (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). A five–factor model, with all items loading on their respective factors (i.e., negative rumination, positive rumination, attention to the partner, sharing work-related thoughts with the partner, and relationship satisfaction) on the within–person level (i.e., day–level) and the between–person level (i.e., person–level), showed acceptable model fit and fitted our data significantly better than alternative models with a fewer number of factors. Table 1 displays the estimated fit indices and the Satorra–Bentler scaled chi–square difference test results.

3.6 Statistical Analyses

We conducted multilevel path modeling using Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) which decomposed the variance of all study variables into their day–level and person–level components (Zhang et al., 2009). With respect to the hypothesis test, we were particularly interested in the day-level results because they represent the presumed daily variation of the psychological constructs within a person. Moreover, we examined the 95% confidence intervals of the indirect associations between negative and positive rumination about work and both partners’ relationship satisfaction via actor’s attention to the partner, applying the Monte Carlo method (Preacher & Selig, 2010) with 1,000,000 repetitions.

We tested our hypotheses in two separate multilevel path models: One model contained all hypothesized paths following the predictor negative rumination, the other model included all hypothesized paths following the predictor positive rumination. We restricted the model parameters as measure addressing collinearity of our two predictor variables (see Dormann et al., 2013; Grewal et al., 2004): Negative and positive rumination correlate at 0.38 on the daily within-person level and at 0.86 at the person-level (see also Table 2). When two predictor variables are correlating within a multiple regression analyses it means that changes in one predictor variable are associated with shifts in the other predictor variable, which makes it impossible to unravel the relationship between each independent variable and the dependent variable. In other words, collinearity can lead to serious stability problems due to inaccurate estimates of coefficients and standard errors, making interpretations of the regression coefficients invalid (Dormann et al., 2013; Marsh et al., 2004) by increasing the type II error (Grewal et al., 2004). The procedure of splitting the model into two in case of correlating predictor variables has been reported before, for example in case of unreasonable and unnecessary work tasks (Sonnentag & Lischetzke, 2018), of excessive and compulsive workaholism (Barber & Santuzzi, 2015), and of two different measurements of gender equality (Meisenberg & Woodley, 2015).

4 Results

Table 2 displays the means, standard deviations, intra–class correlations, zero–order correlations, and reliabilities on the day- and person-levels based on a model with all study variables (which was separate from the two models in which we tested our hypotheses). Reliabilities represent the consistency of results across the items within a scale across all study days. As recommended by Geldhof et al., (2014), Cronbach’s α reliabilities were estimated using a multilevel approach in Mplus in which the numerator of each level-specific α is the squared number of items multiplied by the average covariance at that same level. The denominator of each level-specific α is the sum of all indicator variances and two times each covariance (Geldhof et al., 2014).

4.1 Preliminary Analysis for Gender Invariance

Since we did not assume gender variance in the hypothesized effects, we prepared our data by means of an actor–partner interdependence model. Consequently, we could simultaneously examine how much the male partner is influenced by his female partner and how much the female partner is influenced by her male partner. We confirmed the legitimacy of this procedure by first testing for gender-related differences in participants’ responding behavior and secondly testing for gender-related differences in the interrelations of the variables of our model.

First, a measurement invariance check rules out the possibility that statistical results are biased by psychometric responses to the questionnaire differing between male and female respondents (Gistelinck et al., 2018; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016). Thus, gender invariance is assumed if the χ2 fit index of a measurement model that assumes that certain study parameters are gender equal does not significantly differ from the χ2 of models allowing the study parameters to differ between men and women. Following Muthén and Muthén (2017), we conducted configural (i.e., no parameters constrained equal between men and women), metric (i.e., factor loadings constrained equal), and scalar invariance (i.e., factor loadings and item intercepts constrained equal) tests simultaneously.

The model fit of the metric invariance model did not significantly differ from the configural model (Satorra–Bentler scaled Δχ2 = 11.27, correction factor = 1.20, Δdf = 10, p = 0.337), thus our data showed full metric invariance. As the metric model was significantly better than the scalar model (Satorra–Bentler scaled Δχ2 = 26.79, correction factor = 0.99, Δdf = 9, p < 0.05), the data yielded partial scalar invariance. After allowing the intercepts of one item measuring relationship satisfaction (i.e., “Today we got along very well”) to differ between the two genders (women’s M = 5.86; men’s M = 5.65), the fit of the scalar model assuming equal item intercepts no longer differed significantly from the metric model (Satorra–Bentler scaled Δχ2 = 14.70, correction factor = 0.99, Δdf = 9, p = 0.100). Single noninvariant items are unlikely to affect the mean of the latent variable on which we based our hypothesis tests (Byrne et al., 1989; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Consequently, we assume that participants’ gender did not considerably influence their responding behavior.

Secondly, we tested for gender invariance of the correlations between the five latent variables. Thereby, we modeled all possible correlation paths between the five latent variables (i.e., 15). A structural equation model allowing correlations to vary between women and men did not fit the data significantly better than a structural equation model constraining the correlations of all study variables to be equal for female and male participants (Satorra–Bentler scaled Δχ2 = 37.51, correction factor = 1.14, Δdf = 27, p = 0.086). We conclude that participants’ gender did not influence the relationship of the focal variables, allowing us to test our hypotheses by means of gender–invariant multilevel analyses based on an actor–partner interdependence model.

4.2 Preliminary Analysis for Within-Person Consistencies

Before finally testing our hypotheses, we further examined the degree of within-person consistencies in participants’ responses to the items defining a variable at the day-level. Table 2 presents the ICC (intra–class correlation coefficient) referring to the percentage of consistency (as the opposite of variation) calculated with the following formula (see Asparouhov, 2006): variance between person / (variance between person + variance within person). As the ICC of our focal variables ranged between 29% (thought-sharing with the partner) and 69% (relationship satisfaction), there was not substantial within-person consistency, so a day-level data analysis is statistically justified as participants’ responses varied throughout the days of their study participation.

4.3 Hypotheses Test

Table 3 shows the standardized regression estimates on the day–level based on the path model including negative work rumination and Table 4 shows these estimates based on the path model including positive work rumination.

In favor of Hypotheses 1a and 1b, actor’s day–specific negative (see the negative estimate in Table 3) and positive work rumination (see the negative estimate in Table 4) were associated with their reduced attention to the partner.Footnote 1 The following two hypotheses predicted that the actor’s attention to the partner on a given day relates positively to the actor’s (H2) and the partner’s relationship satisfaction on that day (H3). In both path models, the actor’s attention to the partner relates positively to the relationship satisfaction of the actor and the partner. These findings support Hypotheses 2 and 3. Consequently, when considering the actor’s reduced attention to the partner as a mediator, rumination about work indirectly predicted reduced relationship satisfaction for the actor (negative rumination model: β = − 0.10, SE = 0.05, 95% confidence interval [CI] [− 0.1923, − 0.0193]; positive rumination: β = − 0.12, SE = 0.05, 95% CI [− 0.2015 − 0.0496]) and the partner (negative rumination: β = − 0.05, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.1288, − 0.0026]; positive rumination: β = − 0.06, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [− 0.394, − 0.0035]). These results confirm Hypotheses 4 and 5.

In Hypothesis 6, we hypothesized that actor’s sharing of work-related thoughts with the partner attenuates the negative effect of (a) negative and (b) positive work rumination on the actor’s attention to the partner. The interaction between negative work rumination and thought-sharing yielded a nonsignificant coefficient of β = 0.05, SE = 0.04, p = 0.176 and the interaction between positive rumination and thought-sharing yielded a significant coefficient of β = 0.08, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05. However, simple slope analyses indicated that, under low levels (i.e., 2 on a scale from 1 to 7) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner, both negative rumination (B = − 0.35, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) and positive rumination (B = − 0.33, SE = 0.09, p < 0.001) have significant negative associations with actor’s attention to the partner. The associations decrease under medium levels (i.e., 4) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner (negative rumination: B = − 0.25, SE = 0.06, p < 0.001; positive rumination: B = − 0.17, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01) and finally lose their significance under high levels (i.e., 6) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner (negative rumination: B = − 0.15, SE = 0.09, p = 0.151; positive rumination: B = − 0.01, SE = 0.10, p = 0.954). Consequently, our results point toward hypothesis 6 being true. The interactions between negative and positive rumination and sharing work-related thoughts and their effect on attention to the partner are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Finally, as expected, actor’s sharing of work-related thoughts with the partner attenuated the indirect effect between rumination and both partners’ relationship satisfaction via the actor’s attention to the partner: The interaction turned around the indirect negative effect of negative work rumination on actor’s (β = 0.18, SE = 0.08, 95% CI [0.0726, 0.3101]) and partner’s relationship satisfaction (β = 0.10, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.0237, 0.2125]) into a positive indirect effect. Simple slope analyses indicated that, under low levels (i.e., 2) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner, both negative rumination (B = -0.12, SE = 0.07, p = 0.102) and positive rumination (B = -0.12, SE = 0.06, p = 0.060) have negative, almost significant associations with actor’s attention to the partner in the mediation models. The regression estimates rise just above zero under medium levels (i.e., 4) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner (negative rumination: B = 0.03, SE = 0.05, p = 0.597; positive rumination: B = 0.04, SE = 0.05, p = 0.386) and are finally significantly positive under high levels (i.e., 6) of actor’s thought-sharing with the partner (negative rumination: B = 0.17, SE = 0.08, p < 0.05; positive rumination: B = 0.21, SE = 0.08, p < 0.01). The indirect negative effect of positive work rumination on the actor’s (β = 0.21, SE = 0.07, 95% CI [0.1073, 0.3222]) and the partner’s (β = 0.11, SE = 0.06, 95% CI [0.0075, 0.2266]) relationship satisfaction became positive as well when the actors shared their work-related thoughts with the partners. These results support Hypotheses 7a, 7b, 8a, and 8b.

5 Discussion

Rumination about work outside working hours is known to facilitate work spillovers into private life where it does not only affect workers’ psychological experiences and behaviors, but also crosses over to their partners due to their interactions (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). Although the private time is the time of the day the workers spend with their partners, we do not know much of the impact of negative and positive rumination on the daily quality of a couple’s relationship. Consequently, drawing on load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004), we propose and empirically test a cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism linking negative and positive work rumination of one partner to the relationship satisfaction of both partners via an attentional process. Our results confirm our hypothesized cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism based on the load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004) and show the maladaptive nature of rumination in an interpersonal context. More precisely, our results show that, at the day–level, both negative and positive rumination about work relate to workers’ reduced attention to the partner during their time together after work. That is, on days workers had to think more than usual about work outside working hours, they also reported being less attentive to their partners than usual. In turn, on days workers paid more attention to their partners than they do on average, they and their partners felt more satisfied with their relationship than they did on average.

Our results are in line with prior findings that negative rumination competes with limited working memory resources (Cropley et al., 2016; Kirschbaum et al., 1996; Sliwinski et al., 2006; Sneddon et al., 2013) and leads to tension (King & DeLongis, 2014) and negative emotional displays within romantic relationships (Green et al., 2011). Moreover, our results are also in line with the reported positive relationship between workers’ thoughts about work outside working hours and their withdrawal from their partners (King & DeLongis, 2014). As withdrawal is defined as a worker’s desire to be alone and absorbed “in his/her own world” (Repetti, 1989, p. 654), a connection between increased withdrawal and reduced attention to the partner can be assumed. Yet, our findings also extend this line of research and specify a cognitive mechanism predicting an indirect detrimental impact of any kind of ruminative thoughts about work on workers’ romantic relationship.

We theoretically contribute to the literature by introducing a general cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism following rumination about work outside working hours. Rumination can be viewed as cognitive spillover from work as it infiltrates our thoughts and consequently occupies our attention with work-related matters during private time outside working hours. Due to the fact that rumination distracts us from paying attention to the partner and the relationship, it might reduce dyadic interactions and thus also the satisfaction with the relationship. By distracting the actor’s attention, work rumination indirectly also reduces the partner’s relationship satisfaction and thus allows work to cross over and affect another person. Thus, our cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism is an alternative explanation to the theoretically assumed but not empirically supported affective spillover-crossover mechanisms linking thoughts about work to lower—or rather the lack thereof—to relationship satisfaction (see Debrot et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2018).

Moreover, and possibly most interestingly, we could show that the detrimental effect of work rumination on attention to the partner arose regardless of whether work-related thoughts were negative or positive. Thereby, we could reproduce findings of the field of cognitive psychology that thoughts about positive life events can become the center of attention although this life event is (long) past and the individuals’ environmental demands do not require these thoughts (Berntsen, 1996; Brewin, 1999; Klein & Boals, 2001). However, we seem to be the first study to show that positive rumination can have detrimental effects for the ruminator. Detrimental effects following positive work rumination are rather counterintuitive and not in line with previous empirical insights from the field of work psychology that emphasize the beneficial effects of positive work rumination on workers’ wellbeing (e.g., Jimenez et al., 2022; Weigelt et al., 2019). Our study underlines that, next to mastery, work engagement, or personal growth, having positive interpersonal relations is also an important component for workers’ wellbeing (see also Ryff & Singer, 2008).

By demonstrating a mechanism that buffers the detrimental cognitive spillover-crossover mechanisms following work rumination, we further suggest a way for couples to actively intervene in the chain of action and to take control of their own happiness. More precisely, we proposed and proved that the sharing of their negative or positive work-related thoughts attenuated the negative relationship of rumination on attention to the partner. Drawing on rumination theory (Martin & Tesser, 1996), we argue that this is due to a promoted resolution of workers' thoughts about work (i.e., cognitive closure) with the help of dyadic coping together with the partner (see e.g., Bodenmann, 1997; Lin et al., 2016). Following our argumentation on the cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism based on load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004), resolving the work issue should make the limited attentional resources of working memory available again which workers can now direct to the partner. Thereby, our data show that a couple’s conversation about work not only buffers the harmful indirect effect of work ruminations on both partners’ relationship satisfaction. When workers are highly engaged in negative or positive work rumination and share their thoughts with the partner, the detrimental indirect effect of work rumination even turns into a beneficial indirect effect that relates to higher levels of both partners’ relationship satisfaction.

Our study also connects to research on work-nonwork boundaries and workers’ boundary management in terms of separating versus integrating the two life domains (Kossek et al., 2012). In this context, talking about work with the partner can be framed as “cross–realm talk” (Nippert-Eng, 1996) and thus as an activity integrating work and private life. Integrating work and private life is traditionally viewed critically as it easily evokes a conflict between the two life domains over scarce resources such as time and energy (Schoellbauer et al., 2021). However, in today’s 24/7 working society, a strict separation between work and private life is increasingly becoming an unrealizable ideal (Duxbury & Smart, 2011), so it seems increasingly necessary to find ways to deal with the blurring boundaries between work and private life. Thus, pointing toward a beneficial process of an integrating activity is a further unique contribution of this study.

5.1 Strengths and Limitations

Our work has both strengths and limitations. Starting with strengths, we emphasize the sound theoretical foundation of our hypothesized psychological mechanisms based on the load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004) which we further embedded into the intuitive spillover–crossover framework (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). This is especially important as authors have suggested that effective theory borrowing is crucial to advance research on the work-family interface (Matthews et al., 2016). Moreover, we applied a dyadic design in combination with the actor–partner interdependence model. Both were critical in demonstrating that the proposed dyadic effects represent general psychological mechanisms that are independent of individual characteristics of each partner such as gender.

Another strength of the study is its day–level perspective on the spillover–crossover mechanisms that is accounting for the daily variation of the focal variables within a person and a couple. The daily–diary design further allowed us to outline the cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism as well as the buffering mechanism within a certain time. When investigating psychological processes, time should always be considered a crucial factor (Navarro et al., 2015). Moreover, because participants’ reports within the diary questionnaires referred to their most recent experiences and behaviors, we minimized hindsight bias. Finally, we anticipated concerns about common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012) by separating the daily measurement of negative and positive work rumination from the measurement of the other variables.

Our study also shows limitations that potential follow-up studies should consider. First, our study proved the relationship between rumination and attention to the partner while we argued that work rumination reduces workers’ attention to the partner because work-related thoughts occupy the limited attentional resources of workers’ working memories. Yet, since we did not control for other thoughts that might distract attention but are not related to work or to the partner, we cannot draw any conclusion about the specific relevance of work-related thoughts in terms of attention. Moreover, one could argue that we did not capture all relevant mediators in the proposed cognitive spillover process. For us, the occupation of cognitive resources by means of perceptual load produced by work-related thoughts was implied by reduced attention because the measurement of unconscious psychological mechanism is not possible with a questionnaire design based on self-reports. Future research should further collect evidence for the proposed effect of work-related rumination on attention to the partner by conducting experiments or by applying more objective research such as neuropsychological methods.

Second, we argued that attention to the partner relates positively to relationship satisfaction because it is a necessary precondition for interactions to happen between the partners. Yet, we did not capture couples’ interactions because it seemed too sophisticated to ask the participants to rate the quantity of interactions they had with their partner nested within their time together (which they also could spend non-interacting) during an evening after work. Future research could overcome this measurement problem by finding a way to observe couples, for example by audio/video or—more discretely—by letting them wear trackers that recognizes the voices of the partners and count the time in which they are engaged in conversations with each other.

Finally, a limitation of this study is the size and homogeneity of the study sample. Although a small sample size is quite common for couple studies as well as for diary studies, it limits the possibility to statistically control for relevant trait variables of the participants and for other contextual factors that could have an effect on the proposed model. For example, Repetti and Saxbe (2009) identified the emotional and cognitive functioning of individuals and the general potential for conflict within a family as important factors influencing the experiences and behaviors of family members. Moreover, although a homogenous sample (in our case of highly educated, German-speaking knowledge workers) reduces the risk of confounding effects because of large socio-demographic differences (Repetti & Saxbe, 2009), it also limits generalizations to other populations. It is thus up to future research to investigate whether the reported processes can also be observed in couples with other sociodemographic prerequisites.

5.2 Implications for Future Research

Future research should not only overcome the limitations of our study, but also address in more detail three topics that we introduced to work rumination and spillover-crossover research. First, and maybe most importantly, research should find a way to clarify to what extent work rumination generates perceptual load. According to load theory of selective attention (Lavie et al., 2004), “distractors can be excluded from perception when the level of perceptual load in processing task-relevant stimuli is sufficiently high to exhaust perceptual capacity, leaving none of this capacity available for distractor processing. However, in situations of low perceptual load, any spare capacity left over from the less demanding relevant processing will spill over to the processing of irrelevant distractors” (p. 340). In the case of rumination about work during one’s time with the partner, we assumed that rumination is the attentional task whereas the partner is the distraction. However, as already mentioned, by means of self-reports in questionnaires, we did not see ourselves able to directly capture the extend of the perceptual load produced by ruminative thoughts about work. Alternatively, we implicitly assumed that the higher the rumination, the higher the perceptual load.

As load theory literature typically differentiates between low and high perceptual load when it comes to its effect on attention and selection processes, perceptual load may not necessarily build in a linear fashion. Thus, it might be relevant to look for a certain threshold of ruminative perceptual load that differentiates low vs. high perceptual load. Ruminating about work with low perceptual load might leave just enough attentional resources available to direct to the partner so that their relationship quality does not suffer from work rumination, whereas high perceptual load might be too much, so the workers have no attentional resources left for the partner. In this regard, future research should further consider that, when rumination builds up low perceptual load, individual differences become salient. In their review, Murphy et al. (2016) subsumed that individuals of low and high age, with a cognitive impairment, with high absent-mindedness in their everyday lives, with high strain levels, anxiety, and fatigue tend to ignore distractors under lower perceptual load than individuals without these characteristics. Consequently, the relationship quality of individuals with these characteristics should suffer more likely or more often under work rumination.

Second, not only do we lack information on what extend rumination occupies attentional resources, we also do not know on the salience of negative and positive thoughts when they appear simultaneously. Our data yield a correlation of negative and positive work rumination on the daily level which indicates that negative and positive thoughts about work not come exclusively one after the other but often simultaneously or at least in temporal proximity to each other (e.g., within one day). Klein and Boals (2001) speculated that thoughts about negative events might require more cognitive activity overall because they elicited higher amounts of avoidant thinking as compared to thoughts about positive events (Klein & Boals, 2001). However, future research is needed to further explore this notion.

Third and finally, future research should capture couples’ thought-sharing in more detail in order to specify the proposed buffering mechanism. In this study, we captured couples’ talks about workers’ work-related thoughts and did not distinguish between the sharing of negative and positive thoughts. As our results were in favor of our hypotheses, differentiating the sharing of negative and positive thoughts may not matter much with regard to the postulated cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism, yet could add another layer when examining attention processes and rumination in the future. Moreover, future research should clarify the mechanism underlying the disclosed buffering effect of thought-sharing. We only speculated that it is dyadic coping that supported the resolving of workers’ thoughts. Consequently, we still lack knowledge on the level of emotional and practical support sought after by the worker and provided by the partner in conversations (see Shrout et al., 2006) and the partners’ appraisal regarding whether their conversation about a work issue was constructive or destructive (Carroll et al., 2013).

5.3 Conclusion and Practical Implications

We outlined and empirically demonstrated a cognitive spillover-crossover mechanism linking negative and positive rumination about work to the workers’ and their partners’ lower relationship satisfaction on the same day via workers’ lower attention to the partner. Thereby, we showed that not only negative thoughts about work occupy their scarce attentional resources during their private time with the partner, but positive thoughts do this as well and thus can be as detrimental for a couple’s daily relationship satisfaction as negative ones. However, we show that a couple is not helplessly at the mercy of work spilling over into and affecting their relationship quality. Sharing their thoughts about work with each other seems to be a practical way for couples to deal with the detrimental consequences of their ruminative thoughts about work on the quality of their relationship on that day. It is a way for couples to actively intervene in the chain of action and to take control of their own happiness. Furthermore, partners who talk about the work issues they ruminate about seem to even benefit from work rumination because this dyadic coping process increases partners’ attention for each other and, in turn, also their relationship satisfaction. Talking about work, however, probably serves more than just dyadic support or elaboration and thus the release of attentional resources. Especially if romantic partners do not have similar occupations or work for the same organization, talking about work could be a chance to get a glimpse into each other's work lives which increases their intimacy.

Notes

As can be seen in Table 2, there is no significant correlation between negative and positive rumination and attention to the partner, yet the main effect in the path models yielded significance. In the correlation, these relationships most likely suffer from omitted variable bias, since the interaction term as a theoretically relevant factor is excluded. Thus, testing main effects and interaction terms in the same model is recommended to increase the interpretational value of regression coefficients (Jaccard et al., 1990; Li et al., 2019).

References

Asparouhov, T. (2006). General multi-level modeling with sampling weights. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 35, 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/03610920500476598

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz & E. Demerouti (Eds.), New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 54–71). Psychology Press.

Barber, L. K., & Santuzzi, A. M. (2015). Please respond ASAP: Workplace telepressure and employee recovery. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 172–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038278

Bartsch, L. M., Singmann, H., & Oberauer, K. (2018). The effects of refreshing and elaboration on working memory performance, and their contributions to long-term memory formation. Memory & Cognition, 46, 796–808. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-018-0805-9

Berntsen, D. (1996). Involuntary autobiographical memories. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 10, 435–454. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199610)10:5%3c435::AID-ACP408%3e3.0.CO;2-L

Boals, A., & Banks, J. B. (2020). Stress and cognitive functioning during a pandemic: Thoughts from stress researchers. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12, 255–257. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000716

Bodenmann, G. (1997). Dyadic coping: A systemic-transactional view of stress and coping among couples: Theory and empirical findings. Revue Européenne De Psychologie Appliquée, 47, 137–140.

Borghi, A. M., & Fini, C. (2019). Theories and explanations in psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 958.

Brewin, C. R. (1999). Intrusive autobiographical memories in depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 12, 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0720(199808)12:4%3C359::AID-ACP573%3E3.0.CO;2-5

Brosschot, J. F., Pieper, S., & Thayer, J. F. (2005). Expanding stress theory: Prolonged activation and perseverative cognition. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30, 1043–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.008

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J., & Muthén, B. (1989). Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: The issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456

Cardenas, R. A., Major, D. A., & Bernas, K. H. (2004). Exploring work and family distractions: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Stress Management, 11, 346–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.11.4.346

Carroll, S. J., Hill, E. J., Yorgason, J. B., Larson, J. H., & Sandberg, J. G. (2013). Couple communication as a mediator between work–family conflict and marital satisfaction. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35, 530–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-013-9237-7

Casper, A., Tremmel, S., & Sonnentag, S. (2019). Patterns of positive and negative work reflection during leisure time: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24, 527–542. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000142

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9, 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Clauss, E., Hoppe, A., O’Shea, D., González Morales, M. G., Steidle, A., & Michel, A. (2018). Promoting personal resources and reducing exhaustion through positive work reflection among caregivers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23, 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000063

Cook, W. L., & Kenny, D. A. (2005). The actor–partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000405

Cowlishaw, S., Evans, L., & McLennan, J. (2010). Work–family conflict and crossover in volunteer emergency service workers. Work & Stress, 24, 342–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2010.532947

Cropley, M., & Zijlstra, F. R. H. (2011). Work and rumination. In J. Langan-Fox & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Handbook of stress in the occupations. Camberley: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Cropley, M., Zijlstra, F. R. H., Querstret, D., & Beck, S. (2016). Is work-related rumination associated with deficits in executive functioning? Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1524. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01524

Danner-Vlaardingerbroek, G., Kluwer, E. S., Van Steenbergen, E. F., & Van Der Lippe, T. (2013). Knock, knock, anybody home? Psychological availability as link between work and relationship. Personal Relationships, 20, 52–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01396.x

Debrot, A., Siegler, S., Klumb, P. L., & Schoebi, D. (2018). Daily work stress and relationship satisfaction: Detachment affects romantic couples’ interactions quality. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 2283–2301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9922-6

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34

Donahue, E. G., Forest, J., Vallerand, R. J., Lemyre, P.-N., Crevier-Braud, L., & Bergeron, É. (2012). Passion for work and emotional exhaustion: The mediating role of rumination and recovery. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 4, 341–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2012.01078.x

Dormann, C. F., Elith, J., Bacher, S., Buchmann, C., Carl, G., Carré, G., Marquéz, J. R. G., Gruber, B., Lafourcade, B., Leitão, P. J., Münkemüller, T., McClean, C., Osborne, P. E., Reineking, B., Schröder, B., Skidmore, A. K., Zurell, D., & Lautenbach, S. (2013). Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography, 36, 27–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2012.07348.x

Dunlosky, J., & Hertzog, C. (2001). Measuring strategy production during associative learning: The relative utility of concurrent versus retrospective reports. Memory & Cognition, 29, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194918

Duxbury, L., & Smart, R. (2011). The “myth of separate worlds”: An exploration of how mobile technology has redefined work-life balance. In: S. Kaiser, M. J. Ringlstetter, D. R. Eikhof, & M. Pina e Cunha (Eds.), Creating Balance? (pp. 269–284) Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Eurofound and the International Labour Office. (2017). Working anytime, anywhere: The effects on the world of work. Publications Office of the European Union and the International Labour Office. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/wpef18007.pdf.

Ezzedeen, S. R., & Swiercz, P. M. (2007). Development and initial validation of a cognitive-based work-nonwork conflict scale. Psychological Reports, 100, 979–999. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.100.3.979-999

Falconier, M. K., & Kuhn, R. (2019). Dyadic coping in couples: A conceptual integration and a review of the empirical literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 571. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00571

Falconier, M. K., Jackson, J. B., Hilpert, P., & Bodenmann, G. (2015). Dyadic coping and relationship satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.07.002

Forster, S., & Lavie, N. (2007). High perceptual load makes everybody equal. Psychological Science, 18, 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01908.x

Fritz, C., & Sonnentag, S. (2006). Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: The role of workload and vacation experiences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 936–945. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.936

Frone, M. R. (2015). Relations of negative and positive work experiences to employee alcohol use: Testing the intervening role of negative and positive work rumination. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038375

Gistelinck, F., Loeys, T., Decuyper, M., & Dewitte, M. (2018). Indistinguishability tests in the actor-partner interdependence model. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 71, 472–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12129

Green, S. G., Bull Schaefer, R. A., MacDermid, S. M., & Weiss, H. M. (2011). Partner reactions to work-to-family conflict: Cognitive appraisal and indirect crossover in couples. Journal of Management, 37, 744–769. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309349307

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/258214

Grewal, R., Cote, J. A., & Baumgartner, H. (2004). Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: Implications for theory testing. Marketing Science, 23, 519–529. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1040.0070

Hicks, A. M., & Diamond, L. M. (2008). How was your day? Couples’ affect when telling and hearing daily events. Personal Relationships, 15, 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00194.x

International Labour Office. (2012). International Standard Classification of Occupations: ISCO-08. International Labour Office.