Abstract

Although marketing activities are vital for new ventures (NVs) to ensure growth and survival, previous research is silent on how to organize them in firms’ infancy. The entrepreneurship literature focuses on which marketing activities to perform in NVs but not on how to organize these activities, whereas the marketing literature concentrates on how to organize marketing activities in established firms but not in NVs, which face specific opportunities and challenges in their early stage of development. This article aims to tackle this research gap by examining marketing’s role within NVs’ organization. Drawing on in-depth interviews with managers, we identify two key organizational dimensions: marketing’s dispersion (related to the proliferation and, thus, wide anchoring of marketing responsibilities) and marketing’s structuration (related to the manifestation and, thus, deep anchoring of marketing responsibilities). Through a field survey and archival data, we show that marketing’s dispersion enhances NV profitability, while marketing’s structuration decreases it, and that with increasing marketing influence (i.e., power of marketing actors) in NVs and NV maturity (i.e., age and size), this diametrical pattern of effects becomes less pronounced. Overall, the findings provide novel theoretical and practical insights into the organizational design of marketing in firms’ infancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

For firms, the early stage of development is especially crucial, as it is marked not only by specific opportunities, such as market adaptation, but also specific challenges, such as the shortage of human, financial, and customer resources and a dearth of market knowledge (Gruber, 2004; Shepherd et al., 2000). These opportunities and challenges represent inherent characteristics that distinguish new ventures (NVs) from established firms (La Rocca et al., 2013) and are implicitly or explicitly related to marketing in NVs.

Therefore, the role of marketing is of “utmost importance for the success of new ventures” (Gruber, 2004, p. 164). From a behavioral standpoint, marketing’s role involves specific activities that the marketing function is expected to perform (Moorman & Rust, 1999), such as customer, competitor, product, and channel management (Fürst et al., 2017; Homburg et al., 2010a, 2010b, 2013a), whereas from an organizational perspective, marketing’s role pertains to the position of marketing within the firm’s organization, such as the anchoring of corresponding responsibilities (Workman et al., 1998). Given the inherently low level of organization in firms’ infancy, the organizational perspective on marketing’s role may be particularly crucial for NVs – that is, how marketing should be institutionalized within the NV’s organization. In contrast with established firms, in which basic organizational decisions about marketing have typically already been made and frequently refined, defining, for example, how NVs’ marketing responsibilities should be anchored may represent the starting point of marketing’s organizational development. These decisions would not only help clarify firm expectations of employees’ marketing activities, but may also influence employees’ ability to generate, disseminate, and respond to market intelligence, thus affecting NVs’ market orientation and, in turn, profitability. Therefore, insights into the proper organizational design of marketing’s role in NVs are essential.

However, despite the importance of this topic, the entrepreneurship and marketing literature lacks research that adopts an organizational perspective on the role of marketing in NVs – that is, marketing’s institutionalization within the organization in firms’ infancy. Specifically, the entrepreneurship literature examines marketing in NVs, including new technology ventures and startups, typically from a behavioral perspective. Studies in this field investigate entrepreneurial marketing strategies and actions in terms of dimensions of decision-making (e.g., Crick et al., 2020; Eggers et al., 2020; Sadiku-Dushi et al., 2019; Yang, 2018; Yang & Gabrielsson, 2017), resources and capabilities (e.g., Ahmadi et al., 2014; de Jong et al., 2021; Evers et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2020), determinants (e.g., Hallbäck & Gabrielsson, 2013; Kilenthong et al., 2016; Morris et al., 2002; Nouri et al., 2018), and consequences (e.g., Ahmadi & O’Cass, 2016; Alqahtania & Uslay, 2020; Kocak & Abimbola, 2009; Sullivan Mort et al., 2012) or propose further development of entrepreneurial marketing toward entrepreneurial marketing orientation (Jones & Rowley, 2011). Although these entrepreneurship studies have considerably advanced theoretical knowledge on marketing in NVs, they typically investigate what specific marketing activities should be performed in NVs rather than how marketing activities should be organized in NVs.

Moreover, with two exceptions, who focus on the evolution of the marketing function in NVs in general (Ardishvili et al., 1996) or in the context of initial relationship development (La Rocca et al., 2013), the few studies in the marketing literature that do examine the role of marketing within firms’ organization concentrate on established firms. These firms usually already have a marketing subunit in place and thus are typically concerned with the influence (i.e., power) of this subunit in the firm. Consequently, with few exceptions that take a broader view on the role of marketing in the firm (Homburg et al., 2000; Moorman & Rust, 1999; Workman et al., 1998) or the formal organization of the marketing function in the firm (Piercy, 1986), research on the role of marketing within firms’ organization focuses on marketing’s influence, particularly the decision-making power of the marketing department (e.g., Engelen & Brettel, 2011; Feng et al., 2015; Homburg et al., 1999, 2015; Verhoef & Leeflang, 2009; Verhoef et al., 2011) or the chief marketing officer (Homburg et al., 2014a; Nath & Mahajan, 2011). However, given their early stage of organizational development and resulting resource constraints, NVs may not (yet) have a marketing department or chief marketing officer in place (Gruber, 2004; Phua & Jones, 2010). Thus, for NVs, organizational dimensions of marketing’s role other than marketing’s influence might even be more crucial, such as how responsibilities for marketing activities should be anchored within the organization. Therefore, little is known about marketing’s institutionalization and, thus, specific role within firms’ organization in an early stage of development.

Overall, research on marketing in NVs focuses on what marketing activities should be performed but not on how these activities should be organized; the research that does focus on how marketing activities should be organized typically examines the role of marketing within the organization of established firms, which are typically confronted with other, more advanced organizational design issues than those of NVs in their early stage of development. To address this gap in the literature, our research adopts an organizational perspective on the role of marketing in NVs to examine how marketing activities should be organized in firms’ infancy. For this purpose, we conduct in-depth interviews with managers, complemented by institutionalization theory (e.g., DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2004), broad-based work on the role of marketing (e.g., Moorman & Rust, 1999; Workman et al., 1998), and entrepreneurship studies on marketing (e.g., Kilenthong et al., 2016; Nouri et al., 2018), to develop a framework of marketing’s role within NVs’ organization. Subsequently, through a field survey of NVs and archival data on these firms, we examine how key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in the NV affect NV performance, both in general and depending on internal NV characteristics, such as NV maturity (age and size).

As the first in-depth investigation of marketing’s role within NVs’ organization, this research makes three main contributions. First, it identifies two key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs that relate to the width and depth, respectively, of anchoring marketing responsibilities within the NV’s organization and seem particularly relevant for NVs: marketing’s dispersion (i.e., the degree to which actors are widely involved in marketing activities within the NV’s organization) and marketing’s structuration (i.e., the degree to which the NV’s organization provides structure for actors involved in marketing activities). Second, this research offers insights into how these organizational dimensions affect NV performance by providing evidence for market orientation as a key underlying mechanism and showing that the dimensions differ in the valence (positive vs. negative) of their effects. Third, this research reveals insights into whether, and if so, the strength of these effects depends on internal NV characteristics, setting the basis for recommendations on how to adapt the organizational design of marketing’s role in NVs to, for example, the firm’s maturity (age and size).

Development of conceptual framework

To develop our framework, we relied on a two-step procedure consisting of a qualitative study and efforts to ground the resultant findings in theory and literature. After presenting our definition of NVs, we offer details on this two-step procedure, which provides the foundation not only on our framework, but also on the related hypotheses and their testing in our quantitative study.

Definition of NVs

The entrepreneurship and marketing literature largely agrees that age is the only criterion for defining NVs, which is in accordance with the inherent nature of these firms and also indicated by their name (“new”). However, the literature is less consistent on the specific age cutoff, specifying ranges of 6 years (e.g., Amason et al., 2006), 8 years (e.g., Zahra et al., 2002), and 10 years (e.g., Jin et al., 2017). Following the latter category of studies, which includes research in marketing (e.g., Winkler et al., 2020), the entrepreneurial area (e.g., Puig et al., 2014), and strategic management (e.g., Ferguson et al., 2016), we define “new ventures … [as] not more than ten years old” (Winkler et al., 2020, p. 316). Thus, our NV definition also covers start-ups, whereas established firms are older than 10 years.

Overview of procedure

First, to identify organizational dimensions of the role of marketing that are especially relevant for NVs and factors that influence the importance of these dimensions for NV performance, we conducted a qualitative study. Second, to verify and refine our framework, we grounded these qualitative findings in institutionalization theory and linked them to existing literature. Institutionalization theory argues that organizational actions, structures, and members are embedded in social networks and affected by the pressures of conformity and legitimacy (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2004). As a result, they become established and persevere in organizations (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Selznick, 1957). Thus, the theory can contribute to addressing the question of how specific activities, as well as associated actors and structures, become institutionalized in organizations (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; Cardinale, 2018).

Data collection and analysis of qualitative study

We performed in-depth interviews with 30 NV managers. Each respondent represented one firm for an overall number of 30 NVs. The NVs had an average age of 4.93 years (1–9 years) and an average size of 18.7 employees (2–80 employees) and were rooted almost equally in manufacturing (53%) or services (47%) industries. We ensured diversity of respondents in terms of gender (50% female vs. 50% male), age (24–61 years), hierarchical level (57% top-level vs. 43% mid-level), and education (60% business degree vs. 40% technical degree). Most respondents held a general management position (67%), such as CEO or board member, followed by a marketing position (20%), such as marketing director. Interviews lasted, on average, 47 min and were semistructured. Our interview guide included questions related to NV and respondent characteristics, respondents’ understanding of the term “new venture,” and, particularly, the organization of marketing in respondents’ firm. We audiotaped and transcribed all interviews.

To analyze the data, we performed open, axial, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). First, we undertook open coding through line-by-line analysis of the transcripts. In doing so, we identified discrete aspects mentioned by our respondents that related to the role of marketing in their NVs’ organization. We integrated these aspects into a coding plan that included all relevant codes with descriptions and illustrative quotes. To ensure the reliability of our findings, an independent judge coded our data again. The proportional agreement of 0.92 and an index of reliability and a proportional reduction in loss of 0.91 were well above recommended levels, indicating high intercoder reliability (Neuendorf, 2017; Rust & Cooil, 1994). Minor disagreements between judges were resolved through discussion. Second, we conducted axial coding, exploring whether and how the identified aspects were connected with each other, which allowed us to assign these aspects to higher-level categories. Finally, we moved to selective coding, by which we selected our main categories and integrated them into a framework.

Findings of qualitative study and grounding in theory and literature

Verification of NV definition

Though not our primary goal, we asked interviewees, “What criteria would you generally use for labeling a firm as a ‘new venture’?” With one exception, all named age, mostly as the only criterion but complemented by a few other characteristics, such as size, which were, however, significantly less frequently mentioned. Moreover, we asked interviewees, “Up to what age would you consider your firm an NV?” The majority (60%) stated 10 years (or a range including this age, such as 8–10 years), followed by almost a quarter (24%) indicating 5 years (or a range including this age, such as 5–8 years), based on perceived face validity, gut feeling, or rule of thumb. Overall, this finding provided further support for our selection of a 10-year cutoff for the definition of NVs.

Organization of marketing in the NV

We also asked interviewees, “How would you describe the organization of marketing in your firm?” A wide range of different themes emerged. Through our coding procedure, we were able to identify two key higher-level categories of aspects (marketing’s dispersion and marketing’s structuration) and an additional higher-level category of aspects (marketing’s influence), which we subsequently describe in more detail and link to theory and literature. First, many statements related to the share or number of organizational areas and employees responsible for marketing activities. For example, a top-level NV manager of a services firm stated:

We have in fact several units and employees [in our firm] with some responsibility for marketing activities.

Likewise, a top-level NV manager of a manufacturing firm pointed out:

In this firm, when it comes to customer issues, it is down to just one [organizational] area in which some folks, beyond their nonmarketing activities, take care of marketing activities.

Similar statements related to whether all hierarchical levels were involved in marketing activities or only specific ones, and what sites (e.g., headquarters, local units) were in charge of marketing activities. As a mid-level NV manager of a manufacturing firm noted:

Many of us are involved in market-related actions.… [Thus,] these responsibilities are not restricted to a top manager in the headquarters, but … [are] basically anchored at very different places and sites in our firm.

As connecting elements, we found that these aspects refer to various organizational units of the NV and whether these units are involved in marketing activities. Therefore, these aspects reflect the extent to which actors are responsible for and thus broadly engaged in marketing activities in the NV. Thus, these aspects indicate how widely marketing responsibilities are dispersed within the NV’s organization. Consequently, as one key dimension describing marketing’s role within the NV’s organization, we combined these aspects and assigned them to a higher-level category labeled “marketing’s dispersion in the NV”. Support for this construct comes from institutionalization theory, because the dispersion of marketing in the NV closely parallels institutionalization through proliferation of responsibilities and, thus, engagement in related activities across organizational subunits, members, and levels, accompanied by the emergence of behavioral routines, schemes, and scripts for performing these activities (Barley & Tolbert, 1997). Additional support comes from studies that identify, but do not quantitatively examine, cross-functional dispersion of marketing activities as a dimension on which to describe the role of marketing in the organization (Homburg et al., 2000; Workman et al., 1998).Footnote 1

Importantly, we found that marketing’s dispersion is conceptually distinct from two somewhat related concepts, marketing capabilities dispersion and market orientation, which did not emerge from our interviews but from our literature review. Marketing capabilities dispersion is defined as the distribution of marketing capabilities within and outside the firm (Krush et al., 2015). It adopts a resource perspective by referring to a specific form of marketing resources, which are bundles of marketing skills and accumulated marketing knowledge that are exhibited as collective routines. Market orientation is defined as “market information acquisition and dissemination and the coordinated creation of customer value” (Narver & Slater, 1990, p. 21) or “generation of market intelligence, dissemination of the intelligence across departments, and organization-wide responsiveness to it” (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993, p. 53). It adopts a behavioral perspective by referring to specific market-related activities of customer orientation, competitor orientation, and interfunctional coordination (Narver & Slater, 1990; Slater & Narver, 1995) or market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Kohli et al., 1993) and how well each of these activities is performed in the firm. By contrast, marketing’s dispersion adopts an organizational perspective by capturing the extent of prevalence of responsibilities for marketing activities in general within the organization, rather than how well each of these activities is performed.

Second, many interviewees’ statements about the organization of marketing in their firm pertained to a designated marketing department or position. As a mid-level NV manager of a services firm noted:

Marketing … is very present in our structures.… In particular, we have a CMO and a marketing department in which three marketing managers utterly work on marketing tasks.

In contrast, a top-level NV manager of a manufacturing firm stated:

In my firm’s organization, marketing is literally invisible. There’s no marketing department or marketing position.… We even don’t consider marketing as an explicit field of work.

Other related statements referred to explicit marketing tasks or procedures in the NV. For example, a mid-level NV manager of a manufacturing firm indicated:

All our staff [who is] in charge of marketing activities obtains guidance … [which] marketing tasks to perform and what to consider in this context. I guess this is particular important for those [employees] that have other main [functional] responsibility.

As a connecting link, we found that all these aspects refer to various elements of marketing structure and the extent to which they exist in the NV. Consistent with NVs’ early stage of organizational development, these aspects were rather basic in nature, thus covering marketing structure on a generic and general level. Moreover, these aspects related to all actors responsible for marketing activities, whether these activities were their primary or secondary functional responsibility. Specifically, interviewees’ statements about marketing tasks and procedures included actors with both primary and secondary marketing responsibility, and even marketing departments and positions were occasionally mentioned in the context of secondary (vs. primary) marketing responsibility. For example, in some NVs we found a hybrid marketing-related department (e.g., “Corporate Development & Marketing” subunit) or position (e.g., “Innovation & Marketing Manager” located in the R&D subunit) that was responsible for marketing activities but only as secondary functional responsibility. Therefore, these aspects indicate the extent to which the NV’s organization provides structure for actors responsible for marketing activities and, thus, how deeply marketing responsibilities are anchored within the NV’s organization. As another key dimension of marketing’s role within the NV’s organization, we thus merged these aspects and labeled the resulting higher-level category as “marketing’s structuration in the NV”. The basic logic of this construct finds support in institutionalization theory, which argues that institutionalization can occur through structuration, which refers to the manifestation of responsibilities in the organization by providing structure for employees, such as subunits, job positions, tasks, and processes (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; Scott, 2004).

Because in our interviews some aspects related to the installation of a marketing department or manager and, in a few cases, to rule- and policy-related themes, we compared marketing’s structuration with the well-established constructs of departmentalization (or specialization) and formalization. We found that these potentially related constructs conceptually differ from marketing’s structuration. Departmentalization refers to the presence or number of departments in a firm (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Scott, 2008), thus adopting an overall firm view on one structural element, whereas marketing’s structuration adopts a marketing view on various basic structural elements. Theoretically, even if an NV has no marketing department, it could nonetheless score high on departmentalization because of many other departments (e.g., purchasing, finance, human resource, R&D). Conversely, even if the NV has a marketing department, this represents only one specific structural element and thus cannot be equated with high marketing structuration. This reasoning similarly applies to specialization, which refers to the assignment of a narrow scope of responsibilities to subunits (Ruekert et al., 1985; Van de Ven, 1976). Moreover, formalization, which refers to the specification and monitoring of job-related rules and contracts (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Ruekert et al., 1985), focuses on detailed and specific governance mechanisms rather than covering structure on a generic and general level as marketing structuration does.

Furthermore, though not explicitly mentioned in our interviews, we also compared marketing’s structuration with the well-established construct of centralization. Centralization refers to hierarchical decision-making authority within the organization, thus representing the inverse of the amount of delegation in such authority (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Menon & Varadarajan, 1992). As such, it centers on the locus of decision making about activities, whereas marketing’s structuration focuses on the depth of anchoring responsibilities for performing these activities.

Table 1 provides an overview of the two key dimensions of marketing’s role within the NV’s organization. Moreover, it includes a comparison of these dimensions with related constructs.

Overall, from our interviews, marketing’s dispersion and structuration emerged as key organizational dimensions describing the role of marketing in NVs’ organization. Roughly two-thirds of interviewees mentioned aspects related to both dimensions, though with differing emphases. While institutionalization theory provides support for these dimensions, our literature review indicates that these have not been empirically examined in previous research. A potential reason for this gap is the focus of previous research on the organization of marketing in established firms, which differ from NVs in their stage of organizational development and, thus, in the most relevant organizational design issues. Specifically, because NVs are just at the starting point of corporate development, basic organizational issues such as where (i.e., how widely) and to what extent (i.e., how deeply) marketing responsibilities should be anchored within the organization seem to be particularly crucial for them. By contrast, for established firms, in which such basic organizational issues have typically already been handled, more advanced organizational issues move into focus, such as what rules and policies to specify and monitor (i.e., issues of formalization) and how best to establish hierarchical authority within the organization (i.e., issues of centralization). Therefore, marketing’s dispersion and structuration are organizational dimensions that are particularly applicable to NVs, though they could theoretically be applied to established firms as well.

In addition, in our interviews we occasionally found aspects related to marketing actors’ influence, importance, and voice with respect to marketing and nonmarketing issues. Therefore, as an additional dimension of marketing’s role within the NV’s organization, we aggregated these aspects into a higher-level category labeled “marketing’s influence in the NV”. In support of this finding, institutionalization theory argues that a subunit can become established within an organization through influence building, including participation in decision making (Hillman et al., 2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978). In this case, institutionalization is promoted by the subunit’s control over critical resources and actors’ impact on important issues in the firm (Pfeffer, 1981). Further support comes from research that either identifies the influence of the marketing subunit as one dimension of how marketing’s role in the organization can be characterized (Workman et al., 1998) or equates it with the role of marketing in the organization (Homburg et al., 1999, 2015; Verhoef & Leeflang, 2009).

This dimension differs from marketing’s dispersion and structuration in several respects. First, it refers to marketing actors only (i.e., the marketing manager or department), because the power bases of these actors are likely to be their primary marketing responsibility. Second, aspects related to marketing’s influence were mentioned in only about every third interview and, thus, considerably less often than marketing’s dispersion or structuration, indicating a lesser relevance for NVs than the other dimensions. Finally, this dimension is less novel because it has already been examined in established firms.

Overview of framework and constructs

Underlying logic of framework structure

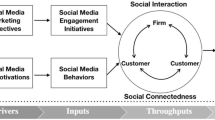

Drawing on our two-step procedure, we developed our conceptual framework. In addition to the construct categories and constructs, Fig. 1 shows the expected relationships between constructs, which we further elaborate on in the “Hypotheses development” section.

The framework focuses on the two previously identified key dimensions describing marketing’s position within the NV’s organization (i.e., marketing’s dispersion and structuration) and their effects on NV performance (i.e., NV profitability). Consistent with prior research suggesting that a firm’s organizational design is likely to influence performance through affecting employees’ market-oriented behavior (Deshpande & Zaltman, 1982; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993), it considers market orientation as a key underlying mechanism of these focal effects. This construct refers to market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness within the NV (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993) and is likely to be particularly important to NVs because it is linked to challenges and opportunities such as dearth of market knowledge, shortage of resources, and market adaptation that distinguish NVs from established firms.

The framework also considers the previously identified additional dimension of marketing’s position within the NV’s organization – that is, marketing’s influence. Because marketing’s influence has a different reference point (i.e., marketing actors only), lesser relevance for NVs, and lesser novelty than marketing’s dispersion and structuration, this internal NV characteristic primarily serves as a moderator of the impact of the two key dimensions on NV performance. To account for the NV’s maturity, our framework includes age and size as additional internal NV characteristics, which also primarily serve as moderators of the impact of the two key dimensions on NV performance. Moreover, we control for potential influences of other internal (i.e., resources and assets), external (i.e., market growth and turbulence), and institutional (i.e., business type and product type) NV characteristics.

Key organizational dimensions of role of marketing in the NV

In line with our organizational perspective on the role of marketing, both dimensions refer to the anchoring of marketing responsibilities within the NV’s organization: marketing’s dispersion indicates how widely and marketing’s structuration how deeply marketing responsibilities are anchored within the NV’s organization.

Marketing’s dispersion in the NV is defined as the degree to which actors are widely involved in marketing activities within the NV’s organization. It is related to the proliferation and, thus, wide anchoring of responsibilities for marketing within the NV’s organization (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; Workman et al., 1998). Greater marketing dispersion is associated with a large share of organizational areas, employees, hierarchical levels, and sites in the NV involved in marketing activities, whereas lesser marketing dispersion is characterized by few organizational areas, employees, hierarchical levels, and sites involved in marketing activities. Marketing’s structuration in the NV is defined as the degree to which the NV’s organization provides structure for actors involved in marketing activities. It is related to the visible manifestation and, thus, deep anchoring of marketing responsibilities within the NV’s organization (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; Fürst & Scholl, 2022; Scott, 2004). Consistent with the dispersion construct, it refers to all actors responsible for marketing activities, whether these are their primary or secondary functional responsibility. Moreover, consistent with NVs’ early stage of development, the construct refers to structural elements that are rather basic and, thus, generic and general in nature. Greater marketing structuration is characterized by designated marketing managers, a designated marketing department, and explicit marketing tasks and procedures in the NV. By contrast, lesser marketing structuration is characterized by the absence of any marketing position, area, task, or procedure in the NV.

Internal NV characteristics

In line with our theoretical discussion that a subunit or member can become institutionalized within an organization through influence building (Hillman et al., 2009; Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), our qualitative study, and previous research (Homburg et al., 1999), our framework treats marketing’s influence in the NV as an additional dimension of marketing’s role within the NV’s organization. This construct captures the exercised power of marketing actors over crucial marketing (e.g., advertising, pricing) and nonmarketing (e.g., strategic direction, new product development) issues (Homburg et al., 1999; Workman et al., 1998). Marketing actors include employees or areas with primary responsibility for marketing, such as the marketing manager or marketing department. Strong marketing influence is associated with substantial decision-making power of marketing actors, whereas weak marketing influence is characterized by a lack of such power. In the latter case, marketing actors only support general management (e.g., CEO) and other actors in their decisions on these issues.

Because the stage of the NV’s development may affect how the firm organizes its marketing activities and performs on the market, the framework considers NV maturity, defined as the extent to which a firm no longer struggles with liabilities of newness, such as early-stage development and the resulting lack of resources and knowledge (Rao et al., 2008; Shepherd et al., 2000). To conceptualize this characteristic, we drew on theoretical concepts (Kazanjian & Drazin, 1990; Quinn & Cameron, 1983) and from studies in entrepreneurship (Hanks et al., 1993) and marketing (Winkler et al., 2020) that relate NV maturity to age and size. NV age refers to the duration in years since the founding of the NV, and NV size captures the overall size of the NV based on the number of employees, rescaled as employee headcount growth (Winkler et al., 2020). These two maturity constructs are conceptually distinct. For example, a relatively young NV could have already grown to a considerable size, or a relatively mature NV could still be fairly small. In addition, our framework includes NV resources (i.e., intangible goods such as brands, patents, and knowledge) and NV assets (i.e., monetary value of overall number of firm resources), as they may influence how the NV designs the role of marketing and how it performs on the market.

External NV characteristics

As environmental factors, the framework includes NV market growth (i.e., the rate of demand growth in the industry in which the NV operates; Song & Chen, 2014) and NV market turbulence (i.e., the rate of change in customers and their preferences; Santos-Vijande & Alvarez-Gonzalez, 2007).

Institutional NV characteristics

To account for the institutional context, we include NV business type (i.e., business-to-consumer vs. business-to-business) and NV product type (i.e., goods vs. services).

NV performance

As a key performance outcome, the framework considers NV profitability, which refers to earnings before interest and taxes (i.e., EBIT; Zhao et al., 2012).

Hypotheses development

Effects of marketing’s dispersion and structuration on NV profitability

Effect of marketing’s dispersion on NV profitability

Previous research indicates that a firm’s organizational system can influence employees’ market-oriented behavior (Deshpande & Zaltman, 1982; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). Thus, we assume that an NV’s organizational design, in which responsibilities for marketing are widespread across areas, employees, hierarchical levels, and sites, promotes firmwide engagement in market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness. These market-oriented activities help the NV efficiently source customer and competitor knowledge and ensure quick market adaptation, thus creating customer value and, in turn, fostering profitability (Fürst & Staritz, 2022; Jaworski & Kohli, 1993; Narver & Slater, 1990). In support of these arguments, a mid-level NV manager of a services firm stated the following in our qualitative study:

[The fact that] many [areas and employees] are involved in marketing activities … creates numerous touchpoints with customers … and competitors … [that serve as sources of] information about what is happening in the market and what it requires, which helps us make the right decisions.

Overall, marketing’s dispersion likely increases market orientation, which ultimately enhances NV profitability. This leads us to predict:

H1

The greater marketing’s dispersion in the NV, the higher is NV profitability.

Effect of marketing’s structuration on NV profitability

Prior research suggests that a strongly defined organizational structure can reduce employees’ market-oriented behavior and, in turn, firm profitability (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). For example, designated job positions and areas may act as information silos and barriers to communication, thus hindering firmwide market intelligence generation and dissemination (Levitt, 1969; Lundstrom, 1976). Moreover, the more strongly structures are prescribed for actors responsible for marketing activities, such as explicit tasks and procedures, the higher the NV’s tendency to maintain the status quo and, thus, the lower its responsiveness to market intelligence, such as changing customer needs or competitor action (Hannan & Freeman, 1984; Ruekert et al., 1985). A lack of market orientation hinders the NV’s efficiency in creating market knowledge and slows down the firm’s reaction to market requirements, thus hampering customer value creation and, in turn, decreasing profitability (Homburg & Fürst, 2007; Kuehnl et al., 2017; Narver & Slater, 1990). In line with this reasoning, a top-level NV manager of a manufacturing firm noted the following in our qualitative study:

We had initially defined specific positions and teams that should take care of marketing [activities] … Later, we noticed that this restricted the flow of [market-related] information, which other people in our firm could have put to good use.

In summary, marketing’s structuration seems to decrease market orientation, which ultimately reduces NV profitability. Thus, we predict:

H2

The greater marketing’s structuration in the NV, the lower is NV profitability.

Effect of marketing’s influence on the impact of marketing’s dispersion and structuration in the NV

When marketing’s influence within the NV is weak, marketing actors have a limited voice in the firm, which impedes their ability to sufficiently contribute their customer- and competitor-related information and shape market-related decision-making (Homburg et al., 1999). In this case, marketing’s dispersion, which promotes firmwide engagement in market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness through a broad anchoring of marketing responsibilities, is particularly crucial for ensuring the NV’s market orientation and, in turn, market knowledge and adaptation to market circumstances, thereby fostering profitability (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). The greater the influence of marketing in the NV, the more marketing actors can contribute their market-related information and persuade other actors to respond to changing customer needs or competitor action. Therefore, increased influence of marketing in the NV reduces the importance of marketing’s dispersion to ensure the NV’s market orientation and, ultimately, profitability.

Moreover, when marketing’s influence in the NV is weak, marketing’s structuration tends to particularly hinder firmwide market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness, thereby reducing profitability. In this case, marketing actors do not have enough power to adequately contribute their market-related information and guide market-related decision-making, which hinders sufficient counterbalancing of the market information silos, barriers to communication about customers and competitors, and inertia in reacting to market requirements resulting from rigid structures (Lundstrom, 1976; Hannan & Freeman, 1984). The greater the influence of marketing in the NV, the more marketing actors can provide customer- and competitor-related information and get involved in market-related decision-making, which mitigates the negative consequences of marketing’s structuration on market orientation and, in turn, profitability. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3

With greater marketing’s influence in the NV, (a) marketing’s dispersion in the NV enhances NV profitability to a lesser degree and (b) marketing’s structuration in the NV decreases NV profitability to a lesser degree.

Effects of NV maturity on the impact of marketing’s dispersion and structuration in the NV

Effect of NV age on the impact of marketing’s dispersion and structuration in the NV

Immediately after an NV’s founding, the market is completely new to the firm. Thus, the NV must newly identify and become acquainted with ways of obtaining and distributing customer- and competitor-related information and using it in market-related decisions (Barley & Tolbert, 1997; Gruber, 2004). In this situation, marketing’s dispersion, which fosters firmwide engagement in market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness, is particularly important for ensuring the NV’s market orientation and, ultimately, its profitability (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). The older the NV, the more time it has had to become familiar with sources and approaches for acquiring and providing customer- and competitor-related information and to implement market-related decision-making processes (Churchill & Lewis, 1983; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Therefore, the NV’s marketing dispersion tends to become less critical for its market orientation and, in turn, profitability (Anderson, 1982).

Furthermore, immediately after an NV’s founding, marketing’s structuration is likely to particularly impede firmwide market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness, thereby decreasing profitability. Specifically, a very young firm has not yet fully explored approaches for acquiring and distributing market-related information and will show particular caution in terms of whether and how to respond to market requirements, thereby impeding sufficient offsetting of the market information silos, barriers to communication about customers and competitors, and inertia to react to market requirements resulting from rigid structures (Lundstrom, 1976; Hannan & Freeman, 1984). As an NV ages, the firm has time to develop approaches for sourcing and providing customer- and competitor-related information and becomes more confident in making decisions about reactions to market requirements, which alleviates the negative consequences of marketing’s structuration on market orientation and, ultimately, profitability. Overall, we predict:

H4

With increasing age, (a) marketing’s dispersion in the NV enhances NV profitability to a lesser degree and (b) marketing’s structuration in the NV decreases NV profitability to a lesser degree.

Effect of NV size on the impact of marketing’s dispersion and structuration in the NV

When an NV is small, it typically has only limited capacity to obtain and distribute customer- and competitor-related information and react to market requirements (Churchill & Lewis, 1983; Kazanjian & Drazin, 1990). In this case, marketing’s dispersion, which promotes firmwide engagement in market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness, is particularly critical for ensuring the NV’s market orientation and, in turn, profitability (Jaworski & Kohli, 1993). The larger an NV becomes, the greater its capacity to gain and distribute insights about the market as well as respond to customer needs and competitor action, which makes marketing dispersion less critical for ensuring market orientation and, ultimately, profitability (Anderson, 1982; Churchill & Lewis, 1983).

In addition, when an NV is small, marketing’s structuration is likely to especially hinder firmwide market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness, thereby reducing profitability. In this case, the firm has not yet fully developed its capacity for sourcing and providing customer- and competitor-related information and reacting to market requirements, which hinders sufficient counterbalancing of the market information silos, barriers to communication about customers and competitors, and inertia to react to market requirements resulting from rigid structures (Lundstrom, 1976; Hannan & Freeman, 1984). As NV size increases, the firm builds up its capacity to obtain and distribute market-related information and respond to customer needs and competitor action, which diminishes the negative consequences of marketing’s structuration on market orientation and, in turn, profitability. Thus:

H5

With increasing size, (a) marketing’s dispersion in the NV enhances NV profitability to a lesser degree and (b) marketing’s structuration in the NV decreases NV profitability to a lesser degree.

Methodology

To increase the validity of our data and reduce the possibility of common method bias, we followed the advice of Podsakoff et al. (2003) to obtain data from different sources. We first collected survey data from NV respondents and then pulled archival data from an official firm database.

Collection of survey data

Sample derivation and composition

To obtain data on the organizational dimensions of the role of marketing in NVs as well as internal, institutional, and external NV characteristics, we carried out a quantitative field survey in Finland, which has an economy and market typical for Europe. First, with the help of a commercial provider of business information (Bisnode AB), we obtained an initial list of NVs. Our sample frame was based on Bisnode’s listing of Finnish firms with a maximum age of 10 years, covering a broad range of industries.

Second, we tried to contact each firm by telephone and to identify an adequate contact person for our survey, resulting in an initial sample of 1,029 NVs. Given NVs’ inherently small number of employees and the relatively broad scope of the survey, typically only one manager (e.g., the CEO, a board member) had sufficient knowledge about the topics of our study. Thus, to ensure high data quality, and consistent with prior studies on marketing’s role in the firm (e.g., Homburg et al., 2015) and marketing in NVs (e.g., Kilenthong et al., 2016), we relied on a key-informant approach. However, in the (few) cases in which another respondent was available in the NV, who also had sufficient knowledge about the topics of our study, we also collected data from this secondary informant for validation purposes. We invited all contact persons to fill out an online questionnaire and offered a report of our study’s key results as an incentive for participation. Our preliminary sample included 227 responses (a response rate of 22.1%). After checking for questionnaire completeness, correct firm age, and informant competence, we obtained a final sample of 206 usable responses of key informants (88% male, mostly CEOs or board members). Moreover, we were able to collect a sample of 32 responses from secondary informants (for validating the responses from key informants) and, about three years after the first wave, a second wave of 95 responses (i.e., 46.1%) from the 206 key informants that had originally participated in our survey (for testing for Granger causality; Granger, 1969). Table 2 provides an overview of our sample.

Checks for nonresponse bias

Following Armstrong and Overton (1977), we checked the answers of early and late respondents (Collier & Bienstock, 2007) and found no indication of nonresponse bias (all differences p > 0.05). Moreover, we compared the NVs we initially addressed with the responding NVs on age, size, and industry and found no significant differences (all p > 0.05). Finally, we compared the NVs in our sample with a subset of NVs that had not originally answered and found no significant differences in age, size, and industry or in marketing’s role in the NV (all p > 0.05).

Checks for key-informant bias

To ensure the validity of key-informant data, we checked for sufficient knowledge about the topics of our study, thereby increasing accuracy of the data (Starbuck & Mezias, 1996). In addition, because of the relatively low organizational complexity, prior research indicates that key-informant data on NVs is likely to show particularly high validity (Homburg et al., 2012; Seidler, 1974). Finally, we conducted several triangulations. Using survey data from the secondary informants, we analyzed the interrater reliability of primary and secondary informants by comparing the within- and between-company variance of responses related to the key constructs in the model on the basis of ICC (1) (intraclass correlation coefficient) (James, 1982). The ICC (1) values range from 0.49 to 0.66, which are very satisfactory (Bliese, 2000; McFarland et al., 2008). Moreover, we correlated these responses with the responses of the key informant for each construct (Celly & Frazier, 1996) and found highly significant correlations between 0.50 and 0.67 (all p < 0.01). We also correlated data on NV size and age from our survey with corresponding archival data (Homburg et al., 2012; Starbuck & Mezias, 1996) and found highly significant correlations of 0.74 and 0.94, respectively (all p < 0.01).

Collection of archival data

To obtain archival data on some general characteristics and performance outcomes of the participating NVs, we drew from an official and publicly available database (Amadeus from Bureau van Dijk). The database contains standard firm data and mandatory financials (e.g., EBIT, balance sheet). All data were collected by one of the authors and, subsequently and independently, double-checked by another author.

Construct measurement

Measurement scales

The Appendix provides an overview of the measurement of each construct in our model. As the literature lacks scales for measuring marketing’s dispersion and marketing’s structuration in the NV, we followed standard scale development procedures (Gerbing & Anderson, 1988). First, from notes and indications in our in-depth interviews, organization theory, and selected statements in prior studies (Piercy, 1986; Workman et al., 1998), we generated a set of five items for each construct. Second, we refined these scales in a pretest with five researchers and five practitioners primarily by clarifying wording. Third, after reviewing the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results, we needed to eliminate one item each from both scales owing to indicator reliabilities below 0.40 (i.e., members of the top management involved in marketing activities and positions at the top management level that primarily refer to marketing, respectively). Resulting scales include four reflective items each.

To measure marketing’s influence in the NV, we drew on an existing formative scale of 11 items (Homburg et al., 1999, 2015). To assess NV age, we relied on data on the founding year and subtracted it from the year of data collection. For NV size, we rescaled the number of employees by using its natural logarithm and relied on the employee headcount growth, thus accounting for the moderately skewed distribution (Winkler et al., 2020).

We applied three items to assess NV resources (Morgan, 2012) and relied on one item related to the financial capital recorded on each NV’s balance sheet to measure NV assets. To measure NV market growth and turbulence, we used three items each (Santos-Vijande & Alvarez-Gonzalez, 2007; Song & Chen, 2014), and to assess NV business type and NV product type, we asked about the firm’s primary business (B2C vs. B2B) and product (goods vs. services) context, respectively (Homburg & Fürst, 2005). Finally, we used the firm’s EBIT margin (i.e., EBIT over sales volume) to operationalize NV profitability. To be able to account for potential time-lag effects between the key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role and NV profitability, we gathered these objective performance data for the year of the measurement of the independent variables and the subsequent year. For hypotheses testing, we followed the common practice of relying on a same-year approach (Kumar et al., 2011), but we also checked the stability of findings when using a one-year-gap approach.

Measurement reliability and validity

We initially ran exploratory factor analysis, finding an unifactorial structure for all reflective constructs. Subsequently, we applied CFA and included all constructs in one multifactorial measurement model, obtaining a satisfactory fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.63; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.93; Tucker–Lewis index [TLI] = 0.91; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.06; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.06). Moreover, we assessed scale reliability and validity for each reflective multi-item construct. Factor loadings of each item are at least 0.63, indicator reliabilities are typically above 0.40, and coefficient alphas and composite reliabilities exceed 0.7. Moreover, average variance extracted (AVE) is above 0.50 in each case. The Appendix includes additional details and psychometric properties for all multi-item constructs.

Discriminant validity

Using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion, we found discriminant validity for each pair of multi-item constructs. For example, we found that the AVEs of marketing’s dispersion (0.61) and marketing’s structuration (0.58) are greater than the squared correlation between the two constructs (0.01), providing evidence that our two key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in the NV are not only conceptually but also empirically different.Footnote 2

Results

Applying maximum likelihood in Mplus, we used covariance-based structural equation modeling (SEM) and found a good overall fit of the predicted model (χ2/df = 1.60; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.05; SRMR = 0.05). Tables 3 and 4 include the estimates for the main- and moderating-effects models.

Results of hypotheses testing

As predicted for our hypothesized main effects, marketing’s dispersion in the NV enhances NV profitability (0.18, p < 0.05; H1), while marketing’s structuration in the NV diminishes NV profitability (–0.17, p < 0.05; H2)Footnote 3Footnote 4. Moreover, for testing our hypothesized moderating effects, we estimated latent interactions (Marsh et al., 2004, 2013). This approach is widely applied across disciplines (MacKenzie et al., 2011; Prigge et al., 2018) and relies on multiplying the indicator(s) of the moderator by the indicator(s) of the predictor. The resulting interactions serve as reflective indicators for measuring the latent interaction on the construct level. Because including an excessive number of interactions in one model can cause serious multicollinearity problems (Cortina, 1993), we followed common practice (Homburg et al., 2013b; Stock & Bednarek, 2014) and estimated three separate interaction models. As expected, our results show that with increasing marketing influence in the NV, marketing’s dispersion enhances NV profitability to a lesser degree (–0.14, p < 0.05; H3a) and marketing’s structuration diminishes NV profitability to a lesser degree (0.16, p < 0.05; H3b). Moreover, with increasing NV age, marketing’s structuration reduces NV profitability to a lesser degree (0.14, p < 0.05; H4b). However, NV age does not moderate the effect of marketing’s dispersion (–0.09, p > 0.05; H4a). In addition, with increasing NV size, marketing’s dispersion increases NV profitability to a lesser degree (–0.15, p < 0.05; H5a) and marketing’s structuration decreases NV profitability to a lesser degree (0.14, p < 0.05; H5b).Footnote 5

Finally, we also compared the fit of the main effects model in Table 3 with the fit of our three interaction models in Table 4. In terms of explained variance, we found that the R2 increased from 0.12 in the main model to between 0.14 and 0.17 in the interaction models. Moreover, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) decreased, indicating better model fit, particularly for interaction models 1 (marketing’s influence as moderator; ΔAIC = –2.89) and 3 (NV size as moderator; ΔAIC = –3.77), and less for interaction model 2 (NV age as moderator; ΔAIC = –0.67).

Results of testing control effects

Though not hypothesized, we also controlled for direct effects of internal, external, and institutional NV characteristics and found some significant relationships. In terms of marketing’s influence, we found a negative relationship to marketing’s dispersion (–0.16, p < 0.05) and a positive relationship to marketing’s structuration (0.15, p < 0.05). In terms of NV maturity, the results indicate a positive effect of NV age on NV profitability (0.15, p < 0.05), whereas NV size decreases marketing’s dispersion (–0.15, p < 0.05) and increases marketing’s structuration (0.33, p < 0.01). Moreover, we found a positive relationship between NV resources and marketing’s structuration (0.22, p < 0.01), NV market growth and marketing’s dispersion (0.15, p < 0.05) and structuration (0.16, p < 0.05), as well as NV market turbulence and marketing’s dispersion (0.17, p < 0.05). Finally, product type is associated with marketing’s structuration (–0.18, p < 0.01), indicating that in services industries, NVs show weaker marketing structuration than in goods industries.Footnote 6 All other effects are nonsignificant (p > 0.05).

Results of checks on stability

To test whether our use of NV performance data from the same year as the data collection on the key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in the NV (same-year approach) affects our findings, we reestimated our main and moderating effects on NV performance data from the year after the year of data collection (t = 1; one-year gap approach). We found that when accounting for time-lag effects, the overall pattern of results remains stable in terms of both direction and strength. Specifically, marketing’s dispersion (0.17, p < 0.05) and structuration (–0.15, p < 0.05) still affect NV profitability. Moreover, marketing’s influence still (weakly) moderates the impact of marketing’s dispersion (–0.11, p < 0.10) and still affects the corresponding impact of marketing’s structuration (0.15, p < 0.05). In addition, while we did not find that NV age moderates the impact of dispersion on NV profitability (p > 0.10), NV age still (weakly) moderates the corresponding impact of structuration (0.12, p < 0.10). Moreover, NV size still moderates the impact of dispersion (–0.14, p < 0.05) and structuration (0.14, p < 0.05) on NV profitability.

Moreover, to check whether to rely on an age of 10 years as the cutoff criterion for NVs affects our findings, we reran our main- and moderating-effects models using 6 and 8 years (see also Yli-Renko et al., 2001). Although the results should be interpreted with caution given the reduced sample size and, thus, statistical power, both the effects of marketing’s dispersion (0.20, p < 0.05) and structuration (–0.26, p < 0.01) on NV profitability for 6 years as the cutoff criterion and the effects of marketing’s dispersion (0.17, p < 0.05) and structuration (–0.24, p < 0.05) on NV profitability for 8 years as the cutoff criterion are still significant. In addition, for both alternative cutoff criteria, the results for the moderating effects are similar to our findings, however, with one previously significant effect (the interaction between NV size and marketing’s dispersion on NV profitability at the cutoff of 8 years) turning into only weak significance (–0.13, p < 0.10).Footnote 7Footnote 8

Results of checks on endogeneity

Although our model contains multiple control variables and is estimated on the basis of dyadic data, we performed several tests to analyze whether our results suffer from endogeneity. First, we tested for common method variance (CMV), which “is essentially a form of omitted variables bias in which unobserved measurement errors correlate across the different latent variables” (Sande & Ghosh, 2018, p. 6). Applying the single common method factor approach, we added a first-order factor with all items of the independent and dependent constructs to our model and re-estimated it (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The pattern of path coefficients remains stable in direction and significance. Moreover, a comparison of our measurement model with a one-factor model in a corresponding CFA (Ramani & Kumar, 2008) yielded a significantly worse model fit (Δχ2 = 1,234.57, Δdf = 38, p < 0.01). In addition, we used the marker variable technique, which assumes that the smallest (or second-smallest) correlation of a marker variable (i.e., a variable that is theoretically unrelated to at least one construct in the model) provides a reasonable proxy for CMV (Lindell & Whitney, 2001; Malhotra et al., 2006). We selected sales force’s communication capability, which meets this requirement, and to be conservative, we used its second-smallest correlation (0.02) as a proxy for CMV. From the correlations between all constructs of our model, we then discounted 0.02 and determined the significance of the adjusted correlations using Malhotra et al.’s (2006) formulas. No correlation related to an effect modeled in our framework changed in significance, and only one other correlation did so (between NV age and NV market turbulence, which turned significant to 0.14, p < 0.05). Overall, these findings indicate that in our data CMV is not a serious concern.

Second, we tested for model misspecification by checking whether our exogenous variables related to marketing’s role and internal NV characteristics are endogenous in nature (Sande & Ghosh, 2018). We applied an instrumental variable approach using investor goodwill, relative market position, prior revenues, relationship with business partners, innovativeness, and customer satisfaction as instruments. All instrumental variables fulfill the requirement of relevance (incremental explanatory power: all p < 0.01) and exogeneity (as confirmed by Sargan tests; χ2 values from 0.16 to 1.15, thus all p > 0.05). Based on these variables, we performed Durbin–Wu–Hausman tests, all of which failed to reject the null hypothesis that our focal constructs related to marketing’s role and internal NV characteristics are exogenous (χ2-values from |.04| to |3.22|, df = 1, thus all p > 0.05).

Third, we tested for omitted selection due to the sample restriction of NV size and applied the two-step correction approach by Heckman (1979). In a first step, we calculated a probit model in which we regressed the NVs’ participation status (participation yes/no) on their prior revenues, assets, age, size, and industry for all participating firms and firms that did not participate in the study but for which we had information on these variables. In a second step, we included the correction term \(\lambda\) (inverse Mills ratio; derived from the results of the probit model) in our main and interaction models. In all models, the impact of the inverse Mills ratio was insignificant (all p > 0.05) and all hypothesized effects remain stable in direction and significance, suggesting that our data do not contain an omitted selection bias.

Fourth, to account for firm-specific, time-varying omitted variables and their effects, we ran unobserved effects models by including prior-year NV profitability (i.e., the performance of the NV at t – 1) into the model (Germann et al., 2015). In the main-effects model (0.33, p < 0.01) and moderating-effects models (between 0.33 and 0.35, all p < 0.01), prior-year NV profitability has a significant effect on NV profitability. Moreover, the direction and significance of the hypothesized effects do not change for the main-effects model (disp = 0.16; struct = –0.16, all p < 0.05) and the moderating-effects models (disp × influence = –0.15, p < 0.05; struct × influence = 0.12, p < 0.05; disp × age = –0.08, p > 0.05; struct × age = 0.16, p < 0.05; disp × size = –0.14, p < 0.05; struct × size = 0.16, p < 0.05). Thus, we found no indication that our analyses are biased by unobserved effects of firm-specific, time-varying omitted variables.

Finally, we also tested for Granger causality (Granger, 1969; see also Chintagunta & Haldar, 1998; Homburg & Luo, 2007). Drawing on longitudinal data on the key constructs in the model, we explored potential reversed causality effects of our two focal constructs (marketing’s dispersion and structuration) on NV size. Corresponding Wald tests suggest that neither marketing’s dispersion nor structuration in t = 0 Granger cause NV size in t = 1 (FDisp_t=0 → Size_t=1 = 0.30, p > 0.05; FStruct_t=0 → Size_t=1 = 0.39, p > 0.05), while NV size in t = 0 Granger causes marketing’s dispersion and structuration in t = 1 (FSize_t=0 → Disp_t=1 = 9.87, p < 0.01; FSize_t=0 → Struct_t=1 = 10.18, p < 0.01). Therefore, we found no evidence for reversed causality effects of our two focal constructs on NV size, but only for the causal direction assumed in our model.

Results of examining further dependent variable

Because often NVs tend to care more about growth than profitability (DeKinder & Kohli, 2008), we re-estimated our main- and moderating-effects models using NV sales growth as alternative dependent variable (“Please rate your firm’s performance relative to main competitors in terms of sales growth”; seven-point scale anchored by “much worse” and “much better”). Similar to the results of the profitability model, the results show that marketing’s dispersion enhances NV sales growth (0.23, p < 0.01), whereas marketing’s structuration reduces it (–0.16, p < 0.05). Moreover, as marketing influence in the NV increases, marketing’s dispersion increases NV sales growth to a lesser degree (–0.14, p < 0.05), whereas the effect of marketing’s structuration on NV sales growth does not change (0.17, p > 0.05). In addition, we found that as NV age increases, marketing’s structuration decreases NV sales growth to a lesser degree (0.15, p < 0.05). In contrast, NV age did not moderate the effect of marketing’s dispersion (0.07, p > 0.05). Finally, we found evidence that as NV size increases, marketing’s dispersion enhances NV sales growth to a lesser degree (–0.17, p < 0.01) and marketing’s structuration reduces NV sales growth to a lesser degree (0.13, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Implications for research

Our research provides the first in-depth investigation into the role of marketing in NVs’ organization, thus shedding light on the organizational design of marketing in firms’ infancy. In doing so, it contributes to the literature in several ways.

First, it identifies two key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs—namely, marketing’s dispersion and marketing’s structuration. These dimensions seem particularly relevant for NVs and differ conceptually and empirically from somewhat related dimensions (e.g., marketing’s influence or specialization, formalization, and centralization) that previous research has repeatedly examined in an established firm context (e.g., Homburg et al., 1999; Ruekert et al., 1985). Specifically, our qualitative findings reveal that in contrast with established firms, NVs are confronted with rather basic organizational decisions about marketing, particularly related to the width and depth of anchoring responsibilities for marketing in the organization. While the width of anchoring marketing responsibilities refers to marketing’s dispersion in the NV, the depth of anchoring marketing responsibilities refers to marketing’s structuration in the NV. We find that in firms’ infancy, the decisions about these dimensions seem to be the starting point of marketing’s organizational development, providing the basis for subsequent refinements in later stages when deciding, for example, about specialization, formalization, and centralization.

Second, this research offers insights into how the key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs affect NV performance. It provides evidence that market orientation serves as a key underlying mechanism and shows that marketing’s dispersion and structuration tend to differ considerably in valence of these effects. While, in general, marketing’s dispersion enhances NV profitability, marketing’s structuration impairs it. A reason for this diametrical pattern is that a wide dispersion of responsibilities for marketing activities tends to promote NVs’ market orientation, while a strong structuration of these responsibilities reduces it. In other words, marketing’s dispersion seems to help NVs overcome the lack of market knowledge, which is an inherent characteristic of NVs; the opposite is true for marketing’s structuration.

Third, our research provides insights into whether and, if so, how the performance consequences of the key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs vary depending on several internal NV characteristics. Specifically, it reveals that the less influential marketing is in NVs, the more positive is the impact of marketing’s dispersion on NV performance and the more negative is the impact of marketing’s structuration on NV performance. Thus, the lower the power of marketing actors to contribute their customer- and competitor-related information and shape market-related decision-making, the greater the impact of marketing activities’ anchoring in NVs’ organization on NV performance. In terms of width of anchoring, this finding indicates that assigning marketing responsibilities also to nonmarketing actors can compensate for a weak position of marketing in terms of ensuring sufficient market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness. In terms of depth of anchoring, it indicates that providing distinct structures for actors responsible for marketing activities aggravates the negative consequences of a weak marketing position by further impairing market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness.

Moreover, our research reveals that the younger and smaller the NVs, the more positive is the impact of marketing’s dispersion on NV performance and the more negative is the impact of marketing’s structuration on NV performance. Therefore, the lower NV maturity, the greater is the performance impact on how marketing activities are anchored in NVs’ organization. Directly after an NV’s inception, when the firm must newly identify and become acquainted with ways of sourcing and distributing customer- and competitor-related information and using it for market-related decisions, the width of anchoring marketing responsibilities seems to be especially beneficial for ensuring market orientation and, in turn, NV performance, while the depth of anchoring marketing responsibilities tends to be especially detrimental. As an aside, compared with NV size, NV age shows a less consistent pattern of moderating effects, suggesting that the performance impact of the organizational design of marketing’s role in NVs changes more strongly because the firm becomes more complex (i.e., growth-related reasons) rather than because the NV just becomes older (i.e., time-related reasons).

Finally, we also contribute to the literature on marketing’s role within firms’ organization in general, which implicitly or explicitly concentrates on established firms. For example, some studies suggest that the dispersion of marketing activities is an important aspect of marketing’s role in the firm (e.g., Workman et al., 1998). Our research confirms the importance of considering such dispersion for NVs and shows that this aspect is particularly vital for smaller NVs. Moreover, previous work on the formal organization of the marketing function in the firm highlights its generally positive impact on firm performance (e.g., Piercy, 1986). We found evidence of an unfavorable impact of such structures for NVs, but our findings related to moderating effects indicate that structuration becomes crucial as firms grow older and larger. Thus, our findings do not contradict but somewhat confirm prior findings related to established firms. Overall, our research shows that for NVs, the performance impact of marketing’s role within the organization differs not only across dimensions and NVs’ marketing influence and maturity but also compared with established firms. Nonetheless, we find that the larger and, to some extent, the older NVs become, the more the performance impact of marketing’s role tends to develop into the direction of the results related to established firms. Thus, while not contradicting previous findings, our findings suggest that marketing’s role within the organization of NVs differs from that within the organization of established firms.

Implications for practice

This research provides guidance on how best to design the role of marketing in NVs’ organization. First, given our findings, we urge NV managers to recognize the importance of organizing their firms’ marketing activities for firm success. While after its inception an NV’s initial focus is typically on internal and funding issues, creating an adequate organizational basis for market intelligence generation, dissemination, and responsiveness is vital for addressing the NV’s inherent lack of market knowledge and, in turn, ensuring firm growth and survival. Thus, NV managers should proactively attend to the organizational design of marketing activities right after their firms’ founding.

Second, our qualitative findings show that after a firm’s founding, the decisions to be made about the organizational design of marketing activities are rather basic and particularly refer to where (i.e., how widely) and to what extent (i.e., how deeply) marketing responsibilities should be anchored within the organization. Although these decisions about the width and depth of anchoring marketing responsibilities in the organization are applicable to all firms, they particularly apply to NVs, which are just at the starting point of organizational development. In later development stages, more advanced organizational decisions move to the forefront, in terms of specialization, formalization, and centralization.

Third, our quantitative findings indicate that NV managers should generally rely on a large width (i.e., dispersion) and a small depth of anchoring responsibilities for marketing within the organization. To implement a large width of anchoring marketing responsibilities, a large share of organizational areas, employees, hierarchical levels, and sites should be involved in marketing activities, which tends to foster the NV’s market orientation. For example, finding ideas for new products and optimal product features could also be assigned to the R&D area, pricing may also be done by an accounting manager, and communicating with customers and selling them products may also be undertaken by the CEO. Moreover, in order to realize a small depth of anchoring marketing responsibilities, managers should initially be cautious to rely exclusively on designated positions and areas and prescribe overly strong structures for all actors responsible for marketing activities, such as very detailed tasks and procedures, as doing so may impair the NV’s market orientation.

Fourth, we encourage NV managers to adapt the organizational design of marketing activities to internal characteristics of their firm. For example, when marketing actors (i.e., subunits with primary responsibility for marketing) lack voice and, thus, power in the NV’s decision making, we advise particularly strongly against high marketing structuration, such as through a designated marketing position or area. In this case, we instead particularly strongly recommend wide marketing dispersion, as distributing marketing responsibilities across many shoulders within the organization, including nonmarketing actors with secondary responsibility for marketing, helps ensure that the NV is able to source, distribute, and respond to market information. By contrast, when marketing actors have considerable influence in the NV’s decision making, they are likely to be able to enforce market information sourcing, distribution, and responsiveness. In this case, there is considerably less need for NV managers to rely on a wide anchoring of marketing responsibilities within the NV’s organization. Moreover, directly after the firm’s inception, we strongly advise NV managers to refrain from establishing designated marketing structures, which would considerably reduce the NV’s market orientation. Instead, we strongly recommend wide marketing dispersion in order to benefit strongly from market information sourcing, distribution, and responsiveness. In contrast, when the NV becomes older and larger and, thus, more mature, managers require less to bet on these advantages resulting from a wide anchoring of marketing responsibilities within the NV’s organization. Therefore, our general recommendation to rely on a large width and a small depth of anchoring marketing responsibilities seems to apply particularly well to NVs right after their founding and diminish in clarity with increasing NV maturity, making it unlikely to be directly transferable to established firms.

Limitations and avenues for further research

First, to keep the complexity of our framework on a manageable level, we focused on the performance impact and, thus, consequences of the organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs, while controlling for internal, external, and institutional characteristics. Future research could conceptualize our control variables as determinants and develop hypotheses about their effects on these dimensions.

Second, this article concentrated on marketing’s dispersion and structuration as the two key organizational dimensions of marketing’s role in NVs, while also including marketing influence as an additional dimension in the framework. Although we accounted and checked for relationships between these dimensions, further studies could investigate these effects in more detail. Insights into this issue might help understand potential interdependencies when dealing with these dimensions.

Third, based on the conceptualization of Jaworski and Kohli (1993), which includes market intelligence, dissemination, and responsiveness, we focused on market orientation as a key underlying mechanism of the effects of marketing’s dispersion and structuration on NV profitability, thereby treating it as an aggregate construct to reduce the complexity of our reasoning. Future studies could rely on other conceptualizations (e.g., Narver & Slater, 1990), explore differences between the dimensions of market orientation in strength and valence of these effects, or focus on developing and testing hypotheses about the mediating role of other underlying mechanisms, such as adaptability, resource rigidity, and flexibility, either instead of or in comparison to market orientation.

Fourth, to obtain a large-scale NV sample that allowed deriving findings of high external validity, our research relied on a cross-sectional approach that accounted for longitudinal aspects by considering NV age and size in the model. Further research might want to track the development of NVs over a longer time span using a longitudinal approach.

Fifth, to consider institutional NV characteristics, we focused on NV business type and product type. Further research is necessary within specific NV environments, such as start-up, high-tech or digital NVs.