Abstract

Transition-age youth with foster care involvement (TAY, ages 17–22) are at heightened risk for suicidal behavior. Despite this, mental health screenings are not standardized across child welfare (CW) systems and existing assessment tools are not designed for use with this specific population. As such, TAY are unlikely to be adequately screened for suicide risk and connected with needed services. In this paper, we sought to identify screening and assessment tools that could be effective for use with TAY in CW settings. Using PubMed and PsycINFO, we conducted a search of the current literature to identify some of the most commonly used screening and assessment tools for youth. We then narrowed our focus to those tools that met predefined inclusion criteria indicating appropriateness of use for TAY in CW settings. As a result of this process, we identified one brief screening tool (the ASQ) and four assessments (the SIQ-JR, the C-SSRS, the SHBQ, and the SPS) that demonstrated specific promise for use with TAY. The strengths and limitations of the tools are discussed in detail, as well as the ways that each could be used most effectively in CW settings. We highlight three key points intended to guide social work practice and policy: (1) systematic, routine assessment of mental health and suicide risk across CW settings is critical; (2) the protocol for assessing suicidal behavior in TAY must account for the wide variations in context and service provision; and (3) CW workers administering assessments must be thoughtfully trained on risk identification and the protocol implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

While suicide is a leading cause of death among adolescents in the United States, youth involved in the child welfare (CW) system are significantly more likely than their peers outside of the system to engage in suicidal behavior (Courtney et al., 2016; McMillen et al., 2005). Several studies have found that youth in foster care attempt suicide at more than three times the rate of those in the general population (Evans et al., 2017; Palmer et al., 2021; Pilowsky & Wu, 2006). Transition-age youth (TAY)—those between ages 17 and 22 who are emancipating from foster care—may be at particularly high risk. In a longitudinal study of TAY (The California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study; CalYOUTH), 40.9% of participants reported suicidal ideation and 23.5% reported a suicide attempt by age 17 (Courtney et al., 2014). These numbers are significantly higher than those of the general population, where 12% of adolescents reported suicidal thoughts and 2.5% reported a suicide attempt in 2020 (SAMHSA, 2021).

Despite these high rates, mental health screening is not standardized across CW systems and TAY are unlikely to be adequately screened for suicide risk. Given the number of social workers working in CW settings, whether as frontline workers, supervisors, mental health clinicians or administrators, this is a critical issue for exploration and consideration within our field. CW workers engaging TAY in emancipation planning are in an ideal position to identify suicide risk and connect these youth with needed services. As such, this paper explores and identifies suicide risk screening and assessment tools that might be most relevant and effective for use with TAY in the CW setting.

Background

Risk Profile for Transition-Age Youth

TAY have a distinct risk profile for suicidal behavior. Rates of maltreatment, a well-established risk factor for suicidality in the general population (Norman et al., 2012), are particularly high among youth with CW involvement. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ report on child maltreatment, over 600,000 children were victims of child abuse and neglect in the federal fiscal year of 2020 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2020). Of note, many youth in care experience multiple types of maltreatment throughout childhood, placing them at increased risk for a range of emotional and behavioral issues, including substance use and psychiatric illness (Katz et al., 2017; McMillen et al., 2005).

TAY, in particular, are at elevated risk for psychiatric illness and substance use compared with same-age youth outside of the system (Braciszewski & Stout, 2012; Courtney et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2010), which further increase the risk for suicidal behavior (Mishara & Chagnon, 2016; Schneider, 2009). In the CalYOUTH study, 41.2% of participants (ages 16.75–17.75) were found to have a mental health disorder, 24.8% were found to have a substance use disorder, and 13.6% had both (Courtney & Charles, 2015). The most prevalent diagnoses included major depression, dysthymia, mania and hypomania, psychotic disorders, alcohol dependence, and substance abuse and dependence. A systematic review similarly cited elevated rates across 17 different studies, revealing that youth in care (ages 17–18) were between two and four times more likely than their same-age peers in the general population to have mental health disorders either in their lifetime and/or in the past year (Havlicek et al., 2013).

Social support can mitigate the long-term negative consequences associated with child maltreatment, protecting against mental illness and suicidal behavior (Evans et al., 2022; Katz & Geiger, 2020; Kleiman & Liu, 2013). However, youth involved in the CW system often report low levels of support from both family and peers (Negriff et al., 2015; Pepin & Banyard, 2006). The process of emancipating from care for TAY may be a particularly stressful time that presents many challenges, including employment difficulties, housing instability, and lack of access to healthcare (Dworsky et al., 2013; Lenz-Rashid, 2006). While relationships with friends, family, and professionals have been found to be helpful to TAY during their transition to adulthood, these youth may find it difficult to establish and maintain meaningful relationships given their prior experiences of instability and separation (Katz & Geiger, 2020; Pryce et al., 2017).

Many TAY identify as sexual minorities (Fish et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2014), which can further exacerbate the risk for suicidal behavior. A recent metanalysis found that sexual minority youth were more likely than their heterosexual peers to report suicidal behavior, with transgender youth at the highest risk (di Giacomo et al., 2018). These youth are also at heightened risk for adverse experiences such as bullying and social isolation (Fish et al., 2019; Peitzmeier et al., 2020) and high rates of mental illness and substance abuse (Amos et al., 2020; Marshal et al., 2011). In New York City, 34.1% of youth in foster care identified as LGBTQAI+ and 13.2% identified on the trans spectrum (Sandfort, 2019).

Of note, the COVID-19 epidemic introduced a number of new challenges and stressors in young people’s lives, thereby increasing suicide risk. For example, rates of psychiatric illness have increased dramatically over the course of the pandemic (Czeisler et al., 2020). Social distancing has furthered isolation and may contribute to perceived lack of social support among TAY (Pantell et al., 2020). Additionally, the economic fallout from the pandemic has likely worsened financial vulnerabilities, and instability in the labor market may have exaggerated TAY's challenges finding employment.

Lack of Systematic Mental Health & Suicide Risk Assessment in CW Settings

Despite the high prevalence of suicidal behavior in TAY, mental health screenings are not standardized across the CW system (Cooper et al., 2010; Huber & Grimm, 2004; Kerker & Dore, 2006). Practices and policies related to assessing youth and making appropriate referrals vary across agencies and states (McCarthy et al., 2004). A national survey in 2003 found that over 90% of CW agencies systematically assessed for physical health problems in youth, while under 50% of agencies assessed for mental health problems (Leslie et al., 2003). Unique challenges in CW settings may contribute to the absence of systematic screening and assessment. High caseloads and competing priorities may prohibit workers from having the time necessary to accurately screen and assess for risk (Brown, 2020). Such activities may be deprioritized compared to addressing basic critical needs, such as access to food, housing, or medical care (Brown, 2020). Additionally, frontline workers often lack the appropriate training and supervision to conduct assessment of mental health needs (Kerns et al., 2014) and may feel uncomfortable asking direct questions about sensitive topics such as trauma and abuse (Kerns et al., 2014). Finally, skepticism about the validity of different tools may also contribute to the lack of appropriate screening in these settings (Kerns et al., 2014).

Consequently, TAY are unlikely to be screened for suicide risk. When suicide assessments are conducted, the tools that are used have not been specifically designed for use with TAY nor validated with the population. As such, even the most commonly used tools may not accurately assess risk levels among these youth (Bernanke et al., 2017; Giddens et al., 2014; Miranda et al., 2021a, b). Further, most suicide assessment tools lack a planning component to guide workers on the appropriate next steps depending on the assessment outcome. Without such guidance, CW workers are likely to respond inappropriately to varying levels of suicide risk. For example, workers may under-react by ignoring significant risk level and not seek immediate psychiatric attention, thereby running the risk of youth acting on suicidal ideation. Conversely, CW workers may over-react by unnecessarily sending youth to emergency departments, which can be harmful for TAY with prior negative experiences with services and systems (Molloy et al., 2020).

Current Study

The consequences of unidentified suicide risk among TAY are both costly and concerning, including future mental health issues and suicidal behavior, homelessness, and chronic disability (Bender et al., 2015; D’Eramo et al., 2004; Dworsky et al., 2013; Goldberg et al., 2001). Whether due to a failure to assess risk or to implementation challenges related to assessment, CW workers are missing an important opportunity to identify risk among youth aging out of care and, subsequently, to connect them to mental health treatment before they emancipate from the system and enter adulthood. Given that many of these workers are social workers by training (Whitaker, 2012), this is a relevant area of research with important implications for social workers in CW settings. In this narrative review, we sought to explore and evaluate a selection of empirically validated suicide screening and assessment tools with the goal of identifying those that would be most relevant and effective for use with TAY in the CW setting.

Method

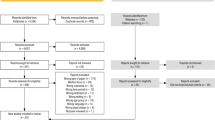

A number of measures have been developed and tested to accurately identify and evaluate suicide risk, including both screening and assessment tools. Screens, which tend to be brief and easy to administer, are used to detect risk of suicide. Assessments, which often follow positive screens, provide a more in-depth evaluation of suicide risk and ultimately inform the subsequent steps to take in response (Boudreaux & Horowitz, 2014). For this paper, we conducted a narrative review of the current literature, which allowed us to broadly examine suicide risk screening and assessment tools utilized with youth and young adults, leverage authors’ expertise within the field of CW, and include manuscripts with varied methodological characteristics (Pae, 2015). As there is no predefined protocol for narrative reviews, we incorporated strategies used in scoping reviews, such as consulting with content area experts, establishing detailed inclusion/exclusion criteria via an iterative process, and summarizing findings (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Searches were conducted using PubMed and PsycINFO (last access 9/17/21) using search terms identified in Table 1 and focused on three key areas/concepts: suicide, tools (and its variations, including measure, scale, etc.) and youth (and its variations, including child, adolescent, etc.). Specifically, we searched for articles with references to suicide and tools in the title and references to youth in the title and/or abstract. We limited our search to articles written in English that were published between 1990 and 2021.

The initial search yielded n = 527 articles in total (n = 275 from PubMed and n = 352 from PsycINFO). The initial search was conducted in both PubMed and PsychINFO due to their complementary characteristics. PubMed is more likely to focus on the basic sciences and medicine-related article and journals, including psychiatry and primary care, whereas PsychINFO is more likely to contain manuscripts related to psychology and allied professions, including the CW population and workforce. Despite significant overlap, both search engines yielded unique citations. With this list, we first conducted a title/abstract review to identify relevant articles. Inclusion criteria for title/abstract review included those articles where suicide screening and assessment tools were created for or used by adolescents and/or young adults (approximately 11–21 years old) in the United States. Additional articles were located by reviewing the reference lists of relevant articles, as well as forward citation-searching to identify if included articles had been cited by other relevant studies. Finally, authors reviewed identified screens and assessments with an expert consultant on suicide assessment, who identified one additional tool to consider. As a result, we compiled n = 34 suicide assessment tools at this stage.

In the next stage of analysis, authors collected the following information for each screening or assessment tool: (1) information on administration and qualifications for assessors (e.g., Master’s level clinician-administered, self-administered); (2) age range for targeted youth/young adults (approximately 11–21 years old); (3) number of questions; (4) information on population assessed in psychometric publications; (5) description of psychometric properties; (6) whether a safety planning component was included with the tool following determination of suicide risk. Based on this information and authors’ experience working in CW settings, we focused on those screening and assessment tools which met the following inclusion criteria: (1) were self-administered or administered by an entry-level staff member without advanced clinical mental health training; (2) could be completed in under 30 min (primarily based on number of questions); (3) had been tested in diverse populations of adolescents/young adults (e.g., racial/ethnic minorities; poverty-impacted youth); (4) retained good psychometric properties across studies (e.g., Cronbach ⍺ ≥ 0.8).

A total of n = 10 screens and assessment tools were retained for further exploration. For each of these 10 assessment tools, authors searched PubMed and PsycINFO (last access 2/21/22) for any publications using the tool within the past 10 years. Searches were conducted using search terms identified in Table 2 and focused on searching for the name of the specific assessment tool and related words such as “suicide.” When there were more than 50 results, we narrowed down the results by eliminating all studies based outside of the U.S., and those that did not include participants who were adolescents or young adults. This was done to make the search more efficient. The results were narrowed by location and participant age in order to target articles that involved populations and contexts that would not be part of the review for elimination. For screening and assessment tools that did not produce relevant publications with the search terms specified, additional articles were located by reviewing each article’s reference lists as well as forward citation-searching to identify if included articles had been cited by other potentially relevant studies. The following information was extracted for each publication utilizing the screening or assessment tool, and is also represented in Table 3: (1) description of population; (2) system involvement (Mental Health, CW, Juvenile Justice, Education, other); (3) whether or not the assessment tool included a low-income population (y/n); (4) whether or not the assessment tool included people of color (y/n); (5) whether or not the assessment tool included adolescents or emerging adolescents (y/n); (6) whether or not the assessment tool included an individualized safety planning piece (y/n); and (7) whether or not the assessment tool was utilized in the U.S. (y/n).

Findings

One brief screening tool designed to quickly identify active suicidal ideation (the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions, ASQ) and four in-depth assessment tools designed to obtain a more thorough history of suicidal ideation and behaviors (The Suicidal Ideal Questionnaire Junior, SIQ-JR; The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, C-SSRS; The Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire, SHBQ; and The Suicide Probability Scale, SPS) met all of our criteria (Eltz et al., 2007; Gutierrez et al., 2001; Horowitz et al., 2012; Posner et al., 2011; Reynolds, 1987;). While these tools might be used at different junctures or administered by various parties in CW context, each demonstrated specific promise for use with TAY.

Brief Screener

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)

The ASQ is a brief screening tool developed by Horowitz et al. (2012) to identify current risk of suicide among patients in pediatric emergency departments (Horowitz et al., 2012). It consists of four yes-or-no questions, as well as a fifth question (“Are you having thoughts of killing yourself right now?”) that is only asked if the patient answers “yes” to any of the first four questions. A positive screen is defined as a “yes” or a refusal to answer any of the first four questions; the fifth question is used to assess suicide risk acuity. An answer of “yes” to the fifth question results in an acute positive screen that requires a safety assessment with full mental health evaluation, while a “no” results in a non-acute positive screen requiring a brief safety assessment to determine if a full mental health evaluation is necessary. The screening can be administered by frontline staff with minimal training. The ASQ was selected as a study instrument in 36 studies relating to suicide within the past 10 years.

The ASQ has good content validity (specificity 87.5–91.2%, 95% CI, sensitivity 100%, 95% CI) and a particularly strong ability to minimize false negative screen results (NPV 99.8–100%) (Aguinaldo et al., 2021; Horowitz et al., 2012, 2013, 2020, 2021). It can be administered in as little as 2-min and can feasibly be used to implement large-scale universal suicide-risk screening programs (Horowitz et al., 2013). The ASQ also retained good psychometric properties when used to assess suicide risk among a fairly racially diverse (45% non-White) sample of pediatric inpatients and among a sample of similarly racially and economically diverse (50% non-White, 33% on public insurance) adolescent outpatients (Aguinaldo et al., 2021; Horowitz et al., 2020). However, at least one study found the ASQ sensitivity score to be significantly lower in Black participants compared to non-Black participants (Horowitz et al., 2012). Additionally, the ASQ has primarily been validated with patients at urban tertiary hospitals (Aguinaldo et al., 2021; Horowitz et al., 2012, 2020). Though it has been used to assess rural patients within the past 10 years, this sample was small, racially homogenous, and older (median age 58.2, SD = 16.3) (LeCloux et al., 2020). As such, the results cannot necessarily be generalized to other non-urban populations.

Assessments

The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire Junior (SIQ-JR)

The SIQ-JR is a 15-item questionnaire developed by Reynolds (1987) to identify and assess suicidal ideation among children and adolescents within the past month. It uses a 7-point scale in which the adolescent rates each item from 0 to 6. Six of the items refer to general ideation (“I thought it would be better if I was not alive”), six items refer to active ideation (“I thought about what to write in a suicide note”), and three items refer to interpersonal problems (“I thought that no one cared if I lived or died”). The questionnaire can be self-administered and is designed to take 5–8 min to complete (Reynolds & Mazza, 1999). Scores range from 0 to 90. A positive screen is determined by a score of 31 or higher. Higher scores indicate greater severity of suicidal ideation.

The SIQ-JR retained good psychometric properties (internal consistency reliability coefficient = 0.93–0.04, test–retest reliability coefficient = 0.89) when used to assess racially and ethnically diverse samples of African American and Latinx youth (Hill et al., 2019; Reynolds & Mazza, 1999). However, there has been some criticism of items 5 (“I thought about people dying”), 8 (“I thought about writing a will”), and 9 (“I thought about telling people I plan to kill myself”), as studies have found improved psychometric properties and model fit when responses to these particular items were excluded from analyses (Hill et al., 2020; King et al., 2008). These items have been criticized as they reference experiences that non-suicidal youth may also endorse, potentially leading to higher scores that may not reflect an adolescent’s actual level of ideation. Additionally, Hill et al. (2020) argues that the fifth item may over-score the level of suicidality in youth from cultures in which thinking about death and dying regularly is more culturally accepted than in mainstream white, American culture.

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

The C-SSRS is a clinical interview tool used to assess suicidal ideation prevalence and intensity, as well as suicidal behavior and its lethality. Currently, there are four versions of the C-SSRS: (1) A paper and electronic Lifetime version assesses both recent and lifetime history of suicidality, while (2) the Since Last Visit version assesses suicidality only since last clinical visit for ongoing patients. The (3) Risk Assessment version includes an additional first page with questions to assess existing risk and protective factors, such as homelessness and the existence of a supportive social network. The (4) Screener version consists of a modified version of the first five items on the Lifetime assessment, detailed below, and an additional sixth question that asks “Have you done anything, started to do anything, or prepared to do anything to end your life?” in the individual’s lifetime or in the last 3 months. This version was developed for quick use by frontline workers and first responders and is the least comprehensive but the simplest to administer and score.

The C-SSRS lifetime version assesses suicidal ideation and behavior both over the course of the patient’s lifetime and in the last month. It consists of 18 items: five to assess for suicidal ideation, six to assess ideation intensity, five to assess suicidal behavior (including non-suicidal self-injurious behavior), and two to assess lethality of suicidal behavior. Although the assessment is designed to be completed during or after a clinical interview, it does not need to be completed by a clinician. However, a C-SSRS certification is required for a non-clinician to administer and score the assessment.

The C-SSRS has good convergent, divergent, and predictive validity, high specificity of suicidal behavior classifications, good sensitivity to change over time in both suicidal ideation and behaviors, and good internal consistency of the behavior intensity subscale (α = 0.937–0.946) (Posner et al., 2011). The C-SSRS was also found to have the most consistently high specificity prediction scores compared to the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation, the SIQ and SIQ-JR, the Suicide Ideation Questionnaire, and the Suicide Probability Scale (SPS) in a meta-analysis review of the psychometric properties of these assessments (Erford et al., 2017). Moreover, the C-SSRS has been successful in assessing a variety of racially and economically diverse adolescent participant samples with good psychometric properties maintained (Arango et al., 2019; Gipson et al., 2015; Gutierrez et al., 2021; Kerr et al., 2014; King et al., 2021; Pfeiffer et al., 2019; Zisk et al., 2017). In particular, it retained good reliability and validity (ICC = 0.953, β = 433–0.656, p < 0.001) when used to assess severely delinquent, low-income, juvenile justice-involved adolescent girls residing in court mandated out-of-home placements (Kerr et al., 2014).

That said, the C-SSRS demonstrates only moderate internal consistency of the ideation subscale (α = 0.73) (Posner et al., 2011). Additionally, the C-SSRS screener version was found to lack sensitivity to suicide risk after patients’ discharge after ED visits related to self-harm, though it was more sensitive in predicting nonfatal self-harm post-discharge (Simpson et al., 2020). Finally, other studies have called into question the wording and logic of the C-SSRS items, as some versions do not use gender neutral language, as is the standard in rating scales to ensure inclusivity for nonbinary respondents (Giddens et al., 2014). The C-SSRS is also susceptible to over-identifying some suicidal ideation types (type I errors) and to under-identifying others (type II errors), particularly among individuals with suicidal ideation, as it utilizes wording that may be susceptible to multiple interpretation, for example whether “‘I have thoughts but I definitely will not do anything about them” refers to not having suicidal ideation but not enacting any suicidal behavior or having suicidal ideation and not seeking any assistance coping with them (Giddens et al., 2014). C-SSRS results also often disagree with the InterSePT Scale for Suicidal Thinking-Plus and Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (Sheehan et al., 2014).

The Self-harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ)

The SHBQ is a self-report measure that was developed by Gutierrez et al. to evaluate suicide-related behaviors and thoughts about suicide (Gutierrez et al., 2001). The SHBQ is divided into four sections: (1) lifetime incidence and frequency of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), (2) suicide attempts, (3) suicide threats, and (4) suicide ideation (Gutierrez et al., 2001). Each section is designed to elicit specific and detailed information that can be coded in a meaningful way, so there are follow up questions in each section asking for examples of related thoughts or behaviors, and questions about intent, lethality, and outcome (Gutierrez et al., 2001). For example, Part C begins with the question, “Have you ever threatened to kill yourself?” Participants who answer “yes” move on to answer several follow up questions that seek information on how many times they have they made a threat, how old they were, what their intent was, who they made the threats to, and context for what else was occurring in their lives at that time (Gutierrez et al., 2001). The SHBQ also provides rich detail due to the free response question formats, which can provide information about the content of suicidal thoughts (Gutierrez et al., 2001). The SHBQ can be administered as a self-report form or conducted as an interview by any frontline worker. It can be scored easily and quickly once frontline workers complete a basic training to ensure they understand the scoring instructions.

The SHBQ was initially validated with a non-clinical sample of university students (95.9% White), and analyses strongly supported the four-factor structure, as well as reliability and convergent validity (α = 0.70–0.77; Gutierrez et al., 2001). The SHBQ has also demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.89–0.96,) and strong test–retest reliability in studies with military personnel, as well as with clinical and non-clinical adolescents (Gutierrez & Osman, 2008; Gutierrez et al., 2001). These psychometric properties were reproduced when the SHBQ was tested with a diverse sample of non-clinical adolescents (57.5% racial/ethnic minority) from a Midwestern public high school (Muehlenkamp et al., 2010).

However, the SHBQ is limited in its generalizability with diverse, clinical, and high-risk adolescent samples, as many validation studies were comprised of low-risk, non-clinical adolescents (Muehlenkamp et al., 2010). While able to distinguish suicidal individuals from non-suicidal individuals, the SHBQ does not clearly distinguish between low and high risk suicidal individuals (Gutierrez et al., 2001). Finally, while the SHBQ can provide more in-depth information than many other suicide assessment measures, its variable length and training needs could make it challenging to administer in busy settings.

The Suicide Probability Scale (SPS)

The SPS is a 36-item self-report measure which provides an overall suicide probability rating based on scores in four areas: suicide ideation, hopelessness, hostility, and negative self-evaluation (Eltz et al., 2007). The SPS takes 5–10 min to administer, a few minutes to score, and can be administered by professionals with a bachelor’s degree (WPS, n.d.). The SPS is comprised of statements such as “I feel hostile towards others,” and “I feel people expect too much of me,” which users rate on a four-point scale based on how often each item is applicable to them (Cull & Gill, 1998; Eltz et al., 2007). Ratings are weighted selectively by item and summed to produce a total weighted score, a normalized T score, a suicide probability score, and four subscale scores (Eltz et al., 2007; Lucey & Lam, 2012). The suicide probability score indicates whether the individual is high, intermediate, or low risk (Bisconer & Gross, 2007).

The SPS has demonstrated high internal reliability with a nonclinical sample of adults and adolescents (α = 0.82–0.86), and inpatient adolescents (α = 0.91) (Cull & Gill, 1998; Eltz et al., 2007). The subscales have internal consistency that ranges from fair to good (α = 0.66–0.86) (Eltz et al., 2007). The SPS has also been validated for use with adolescents (ages 14 and over) in inpatient psychiatric and residential group home settings (Brack et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2012; Eltz et al., 2007; Frazier et al., 2016, 2017; Griffith et al., 2012; Lucey & Lam, 2012;). Further, the SPS has been used with diverse adolescent and adult populations (e.g., Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American), survivors of abuse, people with multiple mental health diagnoses, and youth in foster care (Brack et al, 2012; Brown et al., 2012; Eltz et al, 2007; Frazier et al, 2016, 2017; Griffith et al, 2012; Lucey & Lam, 2012). In addition, the SPS has been utilized to measure changes in suicide risk over the course of inpatient admission, as well as predict risk for readmission among inpatient adolescents (Eltz et al., 2007). Finally, the SPS utilizes simple, behaviorally specific language that is easily understood by adolescents.

There have been some critiques of the subscales of the SPS and arguments for their revision (Eltz et al., 2007). These critiques note that the original developers did not provide a rationale for selecting the previously mentioned four content areas (i.e., suicide ideation, hopelessness, hostility, and negative self-evaluation), and show that the original four factor structure has failed to demonstrate good fit across multiple studies (Bagge & Osman, 1998; Eltz et al., 2007). The SPS has not been tested extensively in the U.S.; further testing is required to determine the effectiveness of this tool for use with American adolescents. Finally, the suicide ideation subscale of the SPS may be especially vulnerable to biased self-report responses, as adolescents are made aware that affirmative disclosures of suicidal intent could result in higher levels of care, such as admittance to an inpatient hospital (Lucey & Lam, 2012).

Discussion

Recent literature has emphasized the critical need for the adoption and integration of universal suicide-risk assessments in CW settings (Brown, 2020). In this study, we sought to identify suicide screening and assessment tools that could be effective for use with TAY specifically. It is our hope that our findings will facilitate screening and assessment tool selection and operationalization for CW administrators and staff looking to routinize mental health and suicide screening. Overall, there are a number of promising assessments available for immediate use with TAY; however, CW administrators would be wise to consider the pros and cons of each assessment prior to selection and implementation. In the next section, we will discuss (a) the importance of routine assessment for all CW involved youth and (b) tool selection based on CW context.

Firstly, routine assessment of mental health and suicidal behavior across CW settings cannot be overemphasized regardless of the screening and assessment tool/s selected. All youth should be assessed upon entry into foster care and ensured appropriate service linkage early on (e.g., mental health, educational; Brown, 2020). Subsequent assessments could align with the periodic planning updates required of all jurisdictions. For example, youth at low risk for suicide could receive a brief screener every 6 to 12 months, coinciding with their routine service plan updates or permanency hearings, and prior to their exit from foster care. Frequent assessment is critical, as risk for suicide among TAY changes throughout late adolescence and early adulthood (Courtney et al., 2020). These routine screenings and assessments could be administered by trained CW caseworkers or alternative frontline CW service providers. Screenings and assessments could also be seamlessly embedded in existing mental health service provision, conducted at need-based intervals by trained mental health clinicians.

Second, any protocol for screening and assessment of suicidal ideation and/or behavior among youth in foster care must account for the wide variations in when, how, and whether youth in care receive appropriate mental health services (Pecora et al., 2009). Health and behavioral health services for youth in foster care are primarily—but not exclusively—paid for using Medicaid funds; as such, the type, volume, and quality of services available varies widely based on each state and locality’s Medicaid programs, its network of enrolled providers, and any procedures that prioritize access for CW involved youth (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2022). Many districts have public employees directly managing every case and monitoring decisions, while some others delegate this duty to a contracted service provider (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). While a small number of districts and agencies employ in-house mental health clinicians, it is common for children in care to be referred outside of the agency to behavioral health clinics or individual providers in their local communities (Leslie et al., 2004; Pecora et al., 2009). For these reasons, it may be difficult to ensure consistent practice in screening and assessment among all behavioral health providers utilized by foster care populations.

However, a systematic approach to assessment is still a worthwhile objective. For instance, administrators may decide, based on a review of existing procedures, that a systemic, routinized protocol is best delivered by CW caseworkers who are responsible for day-to-day management of case activities, but who are unlikely to possess advanced mental health training or clinical credentials. In this case, universal screening may be best achieved by utilizing a brief screening tool (such as the ASQ) that can be administered by a frontline service provider (e.g., a CW caseworker), caregiver, or the youth themselves. If the screening tool indicates an elevated level of risk for suicide, a caseworker or supervisor may initiate a more in-depth assessment of suicidal behavior (such as the C-SSRS) before referral to a mental health provider, if needed.

Limitations

Despite our best efforts to locate potentially relevant studies regarding suicide assessment tools that could be used with TAY in care, it is not guaranteed that all published studies were included in this review. It is possible that using alternative search databases, as well as seeking out additional experts to identify unpublished “grey literature,” may have yielded further resources. While the criteria used to focus our search were informed by our collective direct practice experience in foster care services, it is also possible that search criteria could be better tailored for existing practice through collaboration with actively practicing CW staff.

Implications for Social Work Practice & Policy

In the United States, child welfare service provision is commonly administered by social workers (Whitaker, 2012). Social work practice and child welfare practice have longstanding historical alignment, with social workers staffing the child welfare workforce since the profession’s inception (Perry & Ellett, 2008). Many students emerge from social work degree programs (both at Bachelors (BSW) and Masters (MSW) levels) with specializations in the field of child welfare and are primed to enter the field with targeted expertise in this area (Barbee et al., 2012; Robin & Hollister, 2002; Whitaker, 2012). Given the extremely high rates of child maltreatment and psychiatric illness in the child welfare population (Courtney & Charles, 2015; Courtney et al., 2014; Katz et al., 2020), social workers in this field need to be consistently provided with updated information, training and tools that make effective detection of suicidal behaviors possible. This need is in direct alignment with the ethical principles of the social work profession, especially (1) valuing the inherent worth of every client; (2) valuing the importance and protective nature of human connection; and (3) being highly competent in a chosen field of practice, consistently enhancing professional knowledge in key areas.

Social workers in CW settings that are involved in screening, assessment and service linkage should be thoughtfully trained in (1) signs of suicidal behavior by age, (2) population-specific red flags, and (3) instructions for administering and scoring relevant screening and/or assessment tools. Once significant risk for suicidal behavior has been established, CW agencies need readily available protocols outlining clear instructions on how staff should further assess and address this behavior. Service providers might consider adopting a “path model” for those administering assessments, such as the “Outpatient Behavioral Health Care Clinical Pathway for Assessment and Care Planning for Children and Adolescents at Risk for Suicide” (The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 2019). Such a model would provide staff with step-by-step instructions to follow after determining suicide risk level. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that CW service providers may feel uncomfortable asking suicide-related questions and addressing suicidal behaviors in the youth they serve, necessitating specialized training and ongoing supervision (Norman, 2021).

There is also a need for future social work research in several key related areas. The field would benefit from further research on the suicidal behaviors of youth in care, especially studies that illuminate which youth may be at particularly high risk. Such information would allow under-resourced child welfare service providers to target service provision. Further, the field would benefit from research evaluating the utility and effectiveness of the screenings and assessments mentioned in this paper, specifically for their use with TAY in CW settings. It would be extremely beneficial to explore the extent to which they able to effectively and consistently detect suicide risk in this population. Lastly, qualitative work with TAY could help us better understand the experience of reporting suicidal ideation while in foster care, as youth who are prematurely brought to emergency departments and inpatient psychiatric departments in hospitals after expressing suicidal ideation may be reluctant to disclose future ideation. Such work may be especially valuable for those who serve high-risk youth who report chronic suicidal ideation.

Conclusion

This study offers valuable information relating to the screening and assessment of suicidal behavior in TAY. It is our hope that the findings presented here can facilitate and expedite the screening and assessment protocol establishment process undertaken by CW administrators (and others serving youth with histories of maltreatment and trauma). When used appropriately, each of these screening and assessment tools has the power effectively detect suicidal behavior and save the lives of youth whose risk may have been previously unknown to service providers. In light of the clearly established risk for TAY (Courtney et al., 2014, 2016), the need for systematic and comprehensive suicide assessment is urgent and imperative.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Aguinaldo, L. D., Sullivant, S., Lanzillo, E. C., Ross, A., He, J., Bradley-Ewing, A., Bridge, J. A., Horowitz, L. M., & Wharff, E. A. (2021). Validation of the ask suicide-screening questions (ASQ) with youth in outpatient specialty and primary care clinics. General Hospital Psychiatry, 68, 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.11.006

Amos, R., Manalastas, E. J., White, R., Bos, H., & Patalay, P. (2020). Mental health, social adversity, and health-related outcomes in sexual minority adolescents: A contemporary national cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(1), 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30339-6

Arango, A., Cole-Lewis, Y., Lindsay, R., Yeguez, C. E., Clark, M., & King, C. (2019). The protective role of connectedness on depression and suicidal ideation among bully victimized youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 48(5), 728–739. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2018.1443456

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Bagge, C., & Osman, A. (1998). The suicide probability scale: Norms and factor structure. Psychological Reports, 83(2), 637–638. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.83.6.637-638

Barbee, A. P., Antle, B. F., Sullivan, D. J., Dryden, A. A., & Henry, K. (2012). Twenty-five years of the Children’s Bureau investment in social work education. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 6(4), 376–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2012.705237

Bender, K., Yang, J., Ferguson, K., & Thompson, S. (2015). Experiences and needs of homeless youth with a history of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 55(C), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.06.007

Bernanke, J. A., Stanley, B. H., & Oquendo, M. A. (2017). Toward fine-grained phenotyping of suicidal behavior: The role of suicidal subtypes. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(8), 1080–1081. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.123

Bisconer, S. W., & Gross, D. M. (2007). Assessment of suicide risk in a psychiatric hospital. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 38(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.2.143

Boudreaux, E. D., & Horowitz, L. M. (2014). Suicide risk screening and assessment: Designing instruments with dissemination in mind. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47(3 Suppl 2), S163–S169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.005

Braciszewski, J. M., & Stout, R. L. (2012). Substance use among current and former foster youth: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(12), 2337–2344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.011

Brack, A. B., Huefner, J. C., & Handwerk, M. L. (2012). The impact of abuse and gender on psychopathology, behavioral disturbance, and psychotropic medication count for youth in residential treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(4), 562–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01177.x

Brown, L. A. (2020). Suicide in foster care: A high-priority safety concern. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 665–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619895076

Brown, D. L., Jewell, J. D., Stevens, A. L., Crawford, J. D., & Thompson, R. (2012). Suicidal risk in adolescent residential treatment: Being female is more important than a depression diagnosis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21(3), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9485-9

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2022). Health-care coverage for children and youth in foster care-and after. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children's Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/issue-briefs/health-care-foster/.

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). (2019). Suicide risk assessment and care planning clinical pathway—outpatient specialty care. Retrieved from https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/suicide-risk-assessment-and-care-planning-clinical-pathway.

Cooper, J. L., Banghart, P. L., & Aratani, Y. (2010). Addressing the mental health needs of young children in the child welfare system: What every policymaker should know. National Center for Children in Poverty. Retrieved from https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/text_968.pdf.

Courtney, M. E., & Charles, P. (2015). Mental health and substance use problems and service utilization by transition-age foster youth: Early findings from CalYOUTH. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Courtney, M. E., Charles, P., Okpych, N. J., Napolitano, L., Halsted, K. (2014). Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of foster youth at age 17. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., Charles, P., Mikell, D., Stevenson, B., Park, K., Kindle, B., Harty, J., & Feng. H. (2016). Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of youth at age 19. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Courtney, M. E., Okpych, N. J., Harty, J., Feng, H., Park, S., Powers, J., Nadon, M., Ditto, D. J., & Park, K. (2020). Findings from the California Youth Transitions to Adulthood Study (CalYOUTH): Conditions of youth at age 23. Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Cull, J. G., & Gill, W. S. (1998). Suicide probability scale manual. Western Psychological Services.

Czeisler, M. É., Lane, R. I., Petrosky, E., Wiley, J. F., Christensen, A., Njai, R., Weaver, M. D., Robbins, R., Facer-Childs, E. R., Barger, L. K., Czeisler, C. A., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. (2020). Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(32), 1049–1057. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1

D’Eramo, K. S., Prinstein, M. J., Freeman, J., Grapentine, W. L., & Spirito, A. (2004). Psychiatric diagnoses and comorbidity in relation to suicidal behavior among psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 35(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:chud.0000039318.72868.a2

di Giacomo, E., Krausz, M., Colmegna, F., Aspesi, F., & Clerici, M. (2018). Estimating the risk of attempted suicide among sexual minority youths: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(12), 1145–1152. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2731

Dworsky, A., Napolitano, L., & Courtney, M. (2013). Homelessness during the transition from foster care to adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 103, S318–S323. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301455

Eltz, M., Evans, A. S., Celio, M., Dyl, J., Hunt, J., Armstrong, L., & Spirito, A. (2007). Suicide probability scale and its utility with adolescent psychiatric patients. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 38(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-006-0040-7

Erford, B. T., Jackson, J., Bardhoshi, G., Duncan, K., & Atalay, Z. (2017). Selecting suicide ideation assessment instruments: A meta-analytic review. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1358062

Evans, R., White, J., Turley, R., Slater, T., Morgan, H., Strange, H., & Scourfield, J. (2017). Comparison of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide in children and young people in care and non-care populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Children and Youth Services Review, 82, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.09.020

Evans, R., Katz, C. C., Fulginiti, A., & Taussig, H. (2022). Sources and types of social supports and their association with mental health symptoms and life satisfaction among young adults with a history of out-of-home care. Children, 9(4), 520. https://doi.org/10.3390/children9040520

Fish, J. N., Baams, L., Wojciak, A. S., & Russell, S. T. (2019). Are sexual minority youth overrepresented in foster care, child welfare, and out-of-home placement? Findings from nationally representative data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.005

Frazier, E. A., Liu, R. T., Massing-Schaffer, M., Hunt, J., Wolff, J., & Spirito, A. (2016). Adolescent but not parent report of irritability is related to suicidal ideation in psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(2), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004497

Frazier, E. A., Swenson, L. P., Mullare, T., Dickstein, D. P., & Hunt, J. I. (2017). Depression with mixed features in adolescent psychiatric patients. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 48(3), 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0666-z

Giddens, J. M., Sheehan, K. H., & Sheehan, D. V. (2014). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS): Has the “gold standard” become a liability? Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(9–10), 66–80.

Gipson, P. Y., Agarwala, P., Opperman, K. J., Horwitz, A., & King, C. A. (2015). Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Predictive validity with adolescent psychiatric emergency patients. Pediatric Emergency Care, 31(2), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000225

Goldberg, R. W., Lucksted, A., McNary, S., Gold, J. M., Dixon, L., & Lehman, A. (2001). Correlates of long-term unemployment among inner-city adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Psychiatric Services (washington, D.c.), 52(1), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.101

Griffith, A. K., Smith, G., Huefner, J. C., Epstein, M. H., Thompson, R., Singh, N. N., & Leslie, L. K. (2012). Youth at entry to residential treatment: Understanding psychotropic medication use. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(10), 2028–2035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.05.002

Gutierrez, P. M., & Osman, A. (2008). Adolescent suicide: An integrated approach to the assessment of risk and protective factors. Northern Illinois University Press.

Gutierrez, P. M., Osman, A., Barrios, F. X., & Kopper, B. A. (2001). Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 77(3), 475–490. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08

Gutierrez, P. M., Joiner, T., Hanson, J., Avery, K., Fender, A., Harrison, T., Kerns, K., McGowan, P., Stanley, I. H., Silva, C., & Rogers, M. L. (2021). Clinical utility of suicide behavior and ideation measures: Implications for military suicide risk assessment. Psychological Assessment, 33(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000876

Havlicek, J., Garcia, A., & Smith, D. C. (2013). Mental health and substance use disorders among foster youth transitioning to adulthood: Past research and future directions. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(1), 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.10.003

Hill, R. M., Kaplow, J. B., Oosterhoff, B., & Layne, C. M. (2019). Understanding grief reactions, thwarted belongingness, and suicide ideation in bereaved adolescents: Toward a unifying theory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75, 780–793.

Hill, K., van Eck, K., Goklish, N., Larzelere-Hinton, F., & Cwik, M. (2020). Factor structure and validity of the SIQ-JR in a Southwest American Indian Tribe. Psychological Services, 17(2), 207–216.

Horowitz, L. M., Bridge, J. A., Teach, S. J., Ballard, E., Klima, J., Rosenstein, D. L., Wharff, E. A., Ginnis, K., Cannon, E., Joshi, P., & Pao, M. (2012). Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): A brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 166(12), 1170–1176. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276

Horowitz, L. M., Snyder, D., Ludi, E., Rosenstein, D. L., Kohn-Godbout, J., Lee, L., Kohn-Godbout, T., Farra, A., & Pao, M. (2013). Ask suicide-screening questions to everyone in medical settings: The asQ’em Quality Improvement Project. Psychosomatics, 54(3), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2013.01.002

Horowitz, L. M., Wharff, E. A., Mournet, A. M., Ross, A. M., McBee-Strayer, S., He, J., Lanzillo, E. C., White, E., Bergdoll, E., Powell, D. S., Solages, M., Merikangas, K. R., Pao, M., & Bridge, J. A. (2020). Validation and feasibility of the ASQ among pediatric medical and surgical inpatients. Hospital Pediatrics, 8(9), 750–757. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2020-0087

Horowitz, L. M., Mournet, A. M., Lanzillo, E., He, J., Powell, D. S., Ross, A. M., Wharff, E. A., Bridge, J. A., & Pao, M. (2021). Screening pediatric medical patients for suicide risk: Is depression screening enough? Journal of Adolescent Health, 68, 1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.01.028

Huber, J., & Grimm, B. (2004). Most states fail to meet the mental health needs of foster children. Youth Law News, 24, 1–13.

Katz, C. C., & Geiger, J. M. (2020). “We need that person that doesn’t give up on us”: The role of social support in the pursuit of post-secondary education for transition-aged youth with foster care experience. Child Welfare, 97(6), 145–164.

Katz, C. C., Courtney, M. E., & Novotny, E. (2017). Pre-foster care maltreatment class as a predictor of maltreatment in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 34(1), 35–49.

Katz, C. C., Busby, D., & McCabe, C. (2020). Suicidal behaviour in transition-aged youth with out-of-home care experience: Reviewing risk, assessment, and intervention. Child & Family Social Work, 25(3), 611–618.

Keller, T. E., Salazar, A. M., & Courtney, M. E. (2010). Prevalence and timing of diagnosable mental health, alcohol, and substance use problems among older adolescents in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(4), 626–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.12.010

Kerns, S. E. U., Pullmann, M. D., Putnam, B., Buher, A., Holland, S., Berliner, L., Silverman, E., Payton, L., Fourre, L., Shogren, D., & Trupin, E. W. (2014). Child welfare and mental health: Facilitators of and barriers to connecting children and youths in out-of-home care with effective mental health treatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.013

Kerr, D. C. R., Gibson, B., Leve, L. D., & DeGarmo, D. S. (2014). Young adult follow-up of adolescent girls in juvenile justice using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 44(2), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12072

King, C. A., Woolley, M. E., Kerr, D. C. R., & Vinokur, A. (2008). Factor structure, internal consistency, and predictive validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-Junior (SIQ–JR), in a sample of suicidal adolescents. Unpublished manuscript.

King, C. A., Brent, D., Grupp-Phelan, J., Casper, T. C., Dean, J. M., Chernick, L. S., Fein, J. A., Mahabee-Gittens, E. M., Patel, S. J., Mistry, R. D., Duffy, S., Melzer-Lange, M., Rogers, A., Cohen, D. M., Keller, A., Shenoi, R., Hickey, R. W., Rea, M., Cwik, M., et al. (2021). Prospective development and validation of the computerized adaptive screen for suicidal youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 8(5), 540–549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.4576

Kleiman, E. M., & Liu, R. T. (2013). Social support as a protective factor in suicide: Findings from two nationally representative samples. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(2), 540–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.033

Kerker, B. D., & Dore, M. M. (2006). Mental health needs and treatment of foster youth: Barriers and opportunities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(1), 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.1.138

LeCloux, M. A., Weimer, M., Culp, S. L., Bjorkgren, K., Service, S., & Campo, J. V. (2020). The feasibility and impact of a suicide risk screening program in rural adult primary care: a pilot test of the ask suicide-screening questions toolkit. Psychosomatics, 61(6), 698–706.

Lenz-Rashid, S. (2006). Employment experiences of homeless young adults: Are they different for youth with a history of foster care? Children and Youth Services Review, 28(3), 235–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.03.006

Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M. S., Landsverk, J., Rolls, J. A., Wood, P. A., & Kelleher, K. J. (2003). Comprehensive assessments for children entering foster care: A national perspective. Pediatrics, 112(1 Pt 1), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.112.1.134

Leslie, L. K., Hurlburt, M. S., Landsverk, J., Barth, R., & Slymen, D. J. (2004). Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: A national perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(6), 697–712.

Lucey, C. F., & Lam, S. K. Y. (2012). Predicting suicide risks among outpatient adolescents using the Family Environment Scale: Implications for practice and research. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 34(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-011-9140-6

Marshal, M. P., Dietz, L. J., Friedman, M. S., Stall, R., Smith, H. A., McGinley, J., Thoma, B. C., Murray, P. J., D’Augelli, A. R., & Brent, D. A. (2011). Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 49(2), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005

McCarthy, J., Marshall, A., IIrvine, M., & Jay, B., (2004). An analysis of mental health issues in states’ child and family service reviews and program improvement plans. National Technical Assistance Center for Child and Human Development & American Institutes of Research.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B. T., Scott, L. D., Jr., Auslander, W. F., Munson, M. R., Ollie, M. T., & Spitznagel, E. L. (2005). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(1), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000145806.24274.d2

Miranda, R., Ortin-Peralta, A., Rosario-Williams, B., Flynn Kelly, T., Macrynikola, N., & Sullivan, S. (2021a). Understanding patterns of adolescent suicide ideation: Implications for risk assessment. In R. Miranda & E. L. Jeglic (Eds.), Handbook of youth suicide prevention: Integrating research into practice (pp. 139–158). Springer.

Miranda, R., Shaffer, D., Ortin Peralta, A., De Jaegere, E., Gallagher, M., & Polanco-Roman, L. (2021b). Adolescent Suicide Ideation Interview, version A.

Mishara, B. L., & Chagnon, F. (2016). Why mental illness is a risk factor for suicide. In The international handbook of suicide prevention (pp. 594–608). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118903223.ch34.

Molloy, L., Fields, L., Trostian, B., & Kinghorn, G. (2020). Trauma-informed care for people presenting to the emergency department with mental health issues. Emergency Nurse: THe Journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association, 28(2), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.7748/en.2020.e1990

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Cowles, M. L., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2010). Validity of the self-harm behavior questionnaire with diverse adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 32(2), 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9131-7

Negriff, S., James, A., & Trickett, P. K. (2015). Characteristics of the social support networks of maltreated youth: Exploring the effects of maltreatment experience and foster placement. Social Development (oxford, England), 24(3), 483–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12102

Norman, C. (2021). Asking about suicide and self-harm: Moving beyond clinician discomfort. British Journal of General Practice, 71(706), 217–217. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp21X715793

Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De, R., Butchart, A., Scott, J., & Vos, T. (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

Pae, C. U. (2015). Why systematic review rather than narrative review? Psychiatry Investigation, 12(3), 417–419. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2015.12.3.417

Palmer, L., Prindle, J., & Putnam-Hornstein, E. (2021). A population-based examination of suicide and child protection system involvement. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 69(3), 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.02.006

Pantell, M. S., Kaiser, S. V., Torres, J. M., Gottlieb, L. M., & Adler, N. E. (2020). Associations between social factor documentation and hospital length of stay and readmission among children. Hospital Pediatrics, 10(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2019-0123

Pecora, P. J., Jensen, P. S., Romanelli, L. H., Jackson, L. J., & Ortiz, A. (2009). Mental health services for children placed in foster care: An overview of current challenges. Child Welfare, 88(1), 5–26.

Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), e1–e14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305774

Pepin, E. N., & Banyard, V. L. (2006). Social support: A mediator between child maltreatment and developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 35, 612–625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-006-9063-4

Perry, R. E. & Ellett, A. J. (2008). Child welfare: historical trends, professionalization, and workforce issues. In B. White (Volume Editor) and K. M. Sowers & C. Dulmus (Editors-in-Chief), The comprehensive handbook of social work and social welfare, Volume 1: The Profession of Social Work. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley and Sons.

Pfeiffer, P. N., King, C., Ilgen, M., Ganoczy, D., Clive, R., Garlick, J., Abraham, K., Kim, M., Vega, E., Ahmedani, B., & Valenstein, M. (2019). Development and pilot study of a suicide prevention intervention delivered by peer support specialists. Psychological Services, 16(3), 360–371. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000257

Pilowsky, D. J., & Wu, L. T. (2006). Psychiatric symptoms and substance use disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents involved with foster care. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 38(4), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.06.014

Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, B. A., Yershova, K. V., Oquendo, M. A., Currier, G. W., Melvin, G. A., Greenhill, L., Shen, S., & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

Pryce, J., Napolitano, L., & Samuels, G. M. (2017). Transition to adulthood of former foster youth: Multilevel challenges to the help-seeking process. Emerging Adulthood. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696816685231

Reynolds, W. M. (1987). Suicidal ideation questionnaire (SIQ). Psychological Assessment Resources.

Reynolds, W. M., & Mazza, J. J. (1999). Assessment of suicidal ideation in inner-city children and young adolescents: Reliability and validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire-JR. School Psychology Review, 28(1), 17–30.

Robin, S. C., & Hollister, C. D. (2002). Career paths and contributions of four cohorts of IV-E funded MSW child welfare graduates. Journal of Health & Social Policy, 15(3–4), 53–67.

Sandfort, T. G. (2019). Experiences and well-being of sexual and gender diverse youth in foster care in New York City: Disproportionality and disparities. Retrieved from https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/acs/pdf/about/2020/WellBeingStudyLGBTQ.pdf.

Schneider, B. (2009). Substance use disorders and risk for completed suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 13(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110903263191

Sheehan, D. V., Alphs, L. D., Mao, L., Li, Q., May, R. S., Bruer, E. H., Mccullumsmith, C. B., Gray, C. R., Li, X., & Williamson, D. J. (2014). Comparative validation of the S-STS, the ISST-Plus, and the C-SSRS for Assessing the Suicidal Thinking and Behavior FDA 2012 Suicidality Categories. Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(9–10), 32–46.

Simpson, S. A., Goans, C., Loh, R., Ryall, K., Middleton, M. C. A., & Dalton, A. (2020). Suicidal ideation is insensitive to suicide risk after emergency department discharge: Performance characteristics. Academic Emergency Medicine, 28, 621–629. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14198

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2020). Child Maltreatment 2018. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2008). Child welfare privatization initiatives—assessing their implications for the child welfare field and for general child welfare programs. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/evolving-roles-public-private-agencies-privatized-child-welfare-systems-0.

Whitaker, T. R. (2012). Professional Social workers in the child welfare workforce: Findings from NASW. Journal of Family Strengths, 12(1), 14.

Wilson, B. D., Cooper, K., Kastanis, A., & Nezhad, S. (2014). Sexual and gender minority youth in foster care: Assessing disproportionality and disparities in Los Angeles. UCLA: The Williams Institute. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6mg3n153.

WPS. (n.d.). (SPS) Suicide Probability Scale. Western Psychological Services (WPS). Retrieved from https://www.wpspublish.com/sps-suicide-probability-scale.

Zisk, A., Abbott, C. H., Ewing, S. K., Diamond, G. S., & Kobak, R. (2017). The suicide narrative interview: Adolescents’ attachment expectancies and symptom severity in a clinical sample. Attachment & Human Development, 19(5), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2016.1269234

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Katz, C.C., Gopalan, G., Wall, E. et al. Screening and Assessment of Suicidal Behavior in Transition-Age Youth with Foster Care Involvement. Child Adolesc Soc Work J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00913-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-023-00913-4