Abstract

Labor market institutions (LMIs) could enable new firm entry by lowering burdens to attracting and retaining human capital or restrict new firm entry by increasing concerns of additional demands on ventures facing liabilities of newness and smallness. In this study, we focus on the LMI of the right of association, and whether its relationship with new business entry depends on the vertical ordering of bargaining (represented in the centralization of collective bargaining) or the horizontal synchronization of wage-setting (represented in the coordination of wage-setting). In a panel of 44 countries covering the period 2005–2019, we find that the right of association in the market sector is positively associated with new business entry; however, with increasing centralization of collective bargaining, the association becomes negative. Coordination of wage-setting does not significantly affect the relationship between the right of association and new business entry. The results are robust to accounting for both serial correlation and cross-sectional correlation in the panel regressions and carry implications for policymakers regarding the effects of LMIs on new business creation.

Plain English Summary

Does the right of association influence new business entry? Labor market institutions (LMIs) in a country could be a double-edged sword for new businesses: LMIs can lower human capital competition among smaller and larger firms, but may also increase financial burdens on young and small firms in meeting higher wages and benefits. We find that the right of association in the market sector is positively associated with new business entry; however, with increasing centralization of collective bargaining, the association becomes negative. Coordination of wage-setting does not significantly affect the relationship between the right of association and new business entry. Thus, the principal implication of this study is that labor market institutions may be ex-ante considerations in new firm entry decisions, and the right of association in combination with strong centralization of collective bargaining may jointly lower new business entry.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Labor market institutions (LMIs) represent institutionalized policies, practices, and culture on employees’ rights to association, collective bargaining, and wage-setting. In the labor economics literature, there is a large body of evidence on the impact of LMIs on factors such as labor supply, unemployment, and job search (Freeman, 2008; Holmlund, 2014). LMIs undergird wage and employment conditions to improve the economic and social well-being in society at various levels (Berg, 2015; Nickell & Layard, 1999). Research on the impact of LMIs on entrepreneurship and new business entry is, however, more limited (Block et al., 2019; Burton et al., 2019; Dilli, 2021; Golpe et al., 2008).

The institutional conditions related to LMIs could provide forward-looking expectations for individuals aiming to start a new business. In this study, we focus on the progression of effects of LMIs: The right of association that allows employees to organize in ventures, followed by the effects of the extent of centralization of wage-setting and coordination of wage-setting. Focusing on the relationship between the right of association and new business density and the enabling or restricting effects of centralization and coordination of wages is important from both theoretical and practical vantage points.

Theoretically, LMIs could both enable or restrict new business formation. As an enabler, stricter LMIs provide comparable wages and work conditions making it easier to attract and retain human capital in younger and smaller firms. The institutionalization of expected work conditions and compensation may help reduce turnover and increase commitment from employees. Increased centralization or coordination of wages also creates greater uniformity that lowers labor market competition for ventures. As a restrictor, LMIs could allow for union membership and more stable jobs that could dissuade individuals from pursuing entrepreneurship, a more risky and less stable occupational choice. As individuals consider entrepreneurship at an intensive margin, LMIs could tinge the expectations on the ease or the difficulty of creating a human capital base in their ventures. Stricter LMIs could also impose significant resource demands and burdens on younger and smaller firms that face liabilities of newness and smallness (Pries & Rogerson, 2005). Centralization and coordination of wages also add more resource constraints as larger firms may better meet wage and work conditions than more resource-constrained smaller firms (Atkinson & Storey, 2016; Henrekson, 2020; Nickell & Layard, 1999; Nyström & Elvung, 2014). Overall, LMIs in general could prime more or less favorable expectations among prospective entrepreneurs considering formal new business entry.

Practically, LMIs can also become overly rigid (Berg et al., 2008). In more economically developed countries, the recent pandemic, for instance, has triggered new debates about the need for greater job flexibility. A September 5, 2022, news story on CNN by Isidore (2022), for instance, highlights systemic challenges faced by employees in unionization efforts in the USA. Despite small-scale drives to unionize, larger employers such as Apple, Starbucks stores, and Amazon warehouses attempt to limit such unionization efforts. Nevertheless, with 826 unionization elections between January and July of 2022 and a success rate of 70% in union votes at US businesses, unionization efforts are growing concerns among larger US employers and perhaps a forward-looking consideration for entrepreneurs. The growing need to organize among employees, though not a direct concern for very small firms, could enter into the economic calculus of prospective entrepreneurs.

In this study, we analyze the right of association under vertical ordering (centralization) and synchronization (coordination) of wages (Ahlquist, 2010; Kenworthy, 2001). Centralization is the vertical ordering of wage bargaining, whereas coordination concerns the horizontal relations or synchronization of pay policies among bargaining units (Soskice, 1990). More specifically, centralization refers to “the level at which most bargaining takes place, the degree, and organization of multi-level bargaining, the existence of additional enterprise where there are sectoral or cross-sectoral agreements, the articulation across levels, the hierarchical ordering of agreements, the possibility to derogate from the law by agreements, the tightness of agreements in setting wages, and the use of opening clauses in standard and emergencies” (Visser, 2019, page 8). Coordination is defined as “the degree to which minor players deliberately follow along with what major players decide” (Kenworthy, 2001, page 75), and it is a widely used indicator of bargaining (Nickell, 1997; Soskice, 1990; Traxler & Brandl, 2012). The consideration of vertical and horizontal bargaining, represented in centralization and coordination, respectively, could change the expected benefits from the right of association for entrepreneurial entry.

A particular challenge for analyzing these relationships is that LMIs, including the right of association, are not easy to compare across countries due to their country specificity. For this reason, we draw on the database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention, and Social Pacts (ICTWSS) that provides coding of complex laws across countries (Visser, 2019). We link the relevant data from this data set to information from the World Bank to analyze the relationship between the right of association and new business formation in a panel of 44 countries covering the period 2005–2019. As a measure of new business formation, we use the World Bank’s new business density data which capture the number of newly registered corporations that are private, formal sector companies with limited liability; this measure typically excludes sole-proprietor non-employer establishments (Henrekson & Sanandaji, 2020). Our fixed-effects regressions show that the right of association is positively associated with the new business density in the next year. The empirical analysis also supports the moderation effect for the centralization of collective bargaining; however, we do not find statistical support for a moderating role of the coordination of wage-setting. These results are robust against accounting for both serial correlation and cross-sectional correlation in the panel regressions.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we discuss the theoretical background and develop the hypotheses. In Sect. 3, we present the data sources and the empirical methodology. The results including robustness checks are presented in Sect. 4. We conclude by discussing both theoretical and practical implications in Sect. 5.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

Labor market institutions encompass a variety of labor market regulatory institutions ranging from the right of association to firing laws and from wage centralization and coordination to employee protections (Freeman, 2008; Holmlund, 2014). Collective bargaining studies mainly focus on firm-level bargaining in developed countries, with studies, for instance, finding mixed effects of collective bargaining on unemployment (Blanchflower & Freeman, 1993; Nickell & Layard, 1999; Scarpetta, 1996). Union coverage can lead to wage rigidity, and an increasing trade union density increases tax wedge and unemployment as a consequence (De Serres & Murtin, 2014; Murtin et al., 2014). To address conflicting findings, Calmfors and Driffill (1988) proposed the “hump-shape” hypothesis—that is, intermediate levels of centralization (sectoral bargaining) improve societal outcomes from collective bargaining (Calmfors & Driffill, 1988). However, the hump-shaped hypothesis has received mixed empirical support (Traxler et al., 2001).

More recently, Boeri (2014) proposed “two-tier” bargaining systems where firm-level bargaining improves on sector-level bargaining by enhancing worse outcomes under centralized or decentralized bargaining. In a country-level study, Traxler et al. (2001) found that collective bargaining institutions do not deteriorate macroeconomic performance; however, wage coordination has a larger effect on performance than centralization. In a firm-level study, Braakmann and Brandl (2021) found that businesses covered by coordinated sectoral bargaining, and governed multi-level bargaining systems perform better than businesses covered by the company and national bargaining. Against this background, we now turn to the development of our hypotheses.

2.1 The right of association and new business density

With the weakening power of unions in the neoliberal political institutions across the world, freedom of association remains a powerful mechanism inherited from the International Labor Organization (ILO) labor market reforms since 1919. Freedom of association is related to employee rights to assemble, organize, and run a union. The origins of the right of association in unions can be found in ILO convention 87 which states that “Workers’ and employers’ organizations shall have the right to draw up their constitutions and rules, to elect their representatives in full freedom, to organize their administration and activities and to formulate their programs,” with limited interference from public authorities (Article 3 of the provision), and workers and employers’ organizations cannot “dissolved or suspended by administrative authority” (Article 4). The right of association, therefore, provides the freedom to establish, join, and organize unions without the authority of the state to approve or abolish unions (Peetz, 2021). While bargaining and wage-setting refers to what unions do after they are established, freedom of association refers to the freedom to form a collective institute for representation.

To facilitate cross-country comparisons, Visser (2019) provides coding of complex laws across countries in the Database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts (ICTWSS). The right of association in the market sector is defined as 3 = yes; 2 = yes, with minor restrictions (e.g., recognition procedures, workplace elections, thresholds); 1 = yes, with major restrictions (e.g., monopoly union, prior authorization, major groups excluded); and 0 = no. With an average score of 2.5 in the early 1960s, the average score increased to 2.75 by 2017, with many changes occurring between the 1970s and 1980s. Though recent stability in average scores may indicate isomorphism among countries, the systematic variation in institutional and political factors has also resulted in year-to-year within-country changes in many countries.

The freedom of association in the market sector allows employees to organize at any level of the organization and independently of different employee units (Brandl & Bechter, 2019; Marginson, 2015). As an example, at Starbucks in the USA, the union votes for organizing happen at the store level, and not all stores prefer to unionize. Empirical evidence regarding the relationship between the freedom of association and firm performance is mixed (Grimshaw et al., 2017, page 18), with evidence of higher productivity in Chile, Mexico, Panama, and Uruguay but lower productivity in Argentina (Rios-Avila, 2017). A meta-analysis shows that although union presence tends to increase productivity, the effects differ across countries (Doucouliagos et al., 2017; Grimshaw et al., 2017, page 19). The heterogeneity in the effects is rooted in differences like social dialogues, country contexts, and worker management relationships (Grimshaw et al., 2017, page 18–20).

We hypothesize that though freedom of association may seemingly increase costs for new firms, the long-term benefits for new firms may be much higher. There are three main reasons for this conjecture. First, a significant body of literature on entrepreneurship highlights the value of employee human capital in venture growth (Unger et al., 2011). Ranging from human resource practices necessary to improve the ability, motivation, and opportunity of employees to recruiting and retaining employees, the need to retain employees is more acute as ventures may compete for human capital more directly with larger, more stable firms that are more likely to provide more competitive compensation (Dimov, 2010; Siepel et al., 2017). Freedom of association could signal prospective employees that in case of less competitive pay or work conditions at a venture, and they could engage in collective representation and negotiate better pay or work conditions. Freedom of association levels the playing field on unfair treatment for workers in smaller firms and lowers forward-looking concerns of entrepreneurs in competing with human capital in larger firms.

Second, freedom of association is more likely to be exercised in larger more established firms where employees may have better outcomes from negotiations with the owners. New firms are less established, and employees may be considerate in negotiating stricter terms with owners facing liabilities of newness and smallness (Gimenez-Fernandez et al., 2020). The polarization in varying employee propensities to bargain harder or softer may also increase costs for larger firms, perhaps lowering ex-ante concerns for “hard-balling” by employees preferring to unionize in ventures. With the expectation that human resource policies along with the available freedom of association would allow employees to negotiate fairer and more equitable terms, prospective entrepreneurs may consider strong rights of association as a mechanism to lower frictions in competing for and retention of human capital.

Third, the right of association could also lower labor mobility from ventures (cf. Campbell et al., 2017). Unions increase stickiness as employees associated with unions may feel more secure in their jobs and would therefore be less likely to leave their current position. Freedom of association has positive externalities in labor markets and, in aggregate, can offer a competitive wage schedule, and work conditions to avoid added transaction costs should workers choose to organize. Freedom of association, a precursory requirement before full unionization, creates a more stable equilibrium in labor markets to lower potential imbalance in access to human capital among more established and newer firms. Reduced concerns about accessing human capital could increase new business registrations.

In addition to these reasons that lower concerns for acquiring and retaining human capital, it is also plausible that more freedom of association could dissuade new entry. A higher likelihood of rights to the association may delay venture growth and may systematically curtail the scaling of new ventures. The decline in venturing from such higher direct and indirect labor costs could be detrimental. On the net, however, we expect that improved access to human capital and the ability to retain it through reduced disadvantage in competing for pay and work conditions with more established firms increase new firm entry. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1. The right of association is positively related to new firm establishments.

2.2 The moderating role of the centralization of collective bargaining

According to Windmuller (1987), collective bargaining is “a process of decision making between parties representing employer and employee interests. Its overriding purpose is the negotiation and continuous application of an agreed set of rules to govern the substantive and procedural terms of the employment relationship” (page 3). Collective bargaining can occur through single-employer collective bargaining that takes place in an establishment, company, or division, or on the corporate level between an employer and unions. In a multi-employer collective bargaining setting, an association of employers negotiates with a union or a group of unions. The preference for the degree of centralization in collective bargaining is based on the costs and benefits preferences of actors and institutional conditions (Traxler & Brandl, 2012; Traxler et al., 2001; Zagelmeyer, 2005). Thus, a collective bargaining structure provides modes and roles of interaction, negotiation, and problem-solving (Kochan et al., 1988, page 102) in a complicated network of relationships in which social, administrative, and economic factors are tied together to identify means to set fair wages and work conditions (Oswald, 1979).

Individual employers who prefer to influence collective agreements through increased bargaining power may prefer more centralized bargaining. Industry competitors or local employers sharing labor pools with similar skills then can unite to influence competitive conditions, curb labor costs, or lower mobility. Similarly, unions may prefer to jointly bargain with multiple firms to improve their bargaining structures. A significant body of work in economics, political science, and sociology has focused on the effects of collective bargaining centralization and performance at multiple levels (Blien et al., 2013). The broader arguments in favor of centralized collective bargaining focus on efficiency, and those against it focus on the power argument (Marginson et al., 2003).

We argue that stronger centralization weakens the relationship between the freedom of association and new business entry. Related to the arguments constituting Hypothesis 1, we expect that for entry decisions, the ability to bargain with employees as a firm instead of a collective of firms or unions provides the necessary flexibility to bargain with venture employees. Venture employees represent idiosyncratic skills and culture that may be less effectively represented in a centralized collective bargaining system. As collective bargaining groups of firms try to collate and prioritize the needs of the collective, ventures with relatively limited resources may face increased hurdles in meeting employee needs. To lower transaction costs, more centralized collective bargaining for a large number of individual negotiations increases standardization and may not meet the unique needs of developing employee experiences and structures in ventures. Though the gains of stability and uncertainty reduction and speed of resolution and negotiations from centralization are useful (Calmfors, 1993), for smaller and newer firms, such benefits may come at the expense of the unique human capital milieus that ventures may create. Centralized bargaining can therefore lower competition and improve market control; however, newer firms may already face higher competition, and benefits of reduced competition may mostly be realized by incumbent firms.

More centralized bargaining may focus on reducing labor costs, and reducing outside options for workers; less centralized bargaining may allow ventures to improve their ability to increase their differentiation in the labor market. Less decentralized collective bargaining increases representation and the interests of the employees, gives the workforce the greatest control and power over their representatives, and results in less internal conflict (Kochan et al., 1988). Our second hypothesis, therefore, is as follows:

-

Hypothesis 2. Stronger centralization of collective bargaining weakens the positive relationship between the right of association and new firm establishments.

2.3 The moderating role of the coordination of wage-setting

Coordination of wage-setting or the degree of integration or synchronization in wage policies among different units ranges from no coordination (each company sets wages) to highly coordinated (firms within industries or across sectors set wages). It strengthens the interdependence among bargaining units by reducing wage differentials among firms.

Brandl (2022) provides an overview of the institutional structures and labor market bargaining dynamics on horizontal and vertical bargaining structures. The level and degree of coordination in collective bargaining “increasingly [focuses] towards analyses of the impact of different organizational structures of collective bargaining in which specific configurations of power, interests, and norms have formed … and arguments over their relative importance and implications on outcomes such as wages, employment and (wage) inflation” (Brandl, 2022, page 6). Based on Soskice (1990), Brandl (2022) states that horizontal coordination, through mutually beneficial wage-setting attempts, “can even outperform other forms of bargaining” (Brandl, 2022, page 6). Though vertical coordination, at times, can be beneficial in setting institutional norms and tone for bargaining, horizontal coordination lowers negative externalities and costs due to bargaining among units at the same level and reducing free riding. Considering horizontal and vertical coordination in tandem, low vertical coordination lowers performance with increasing centralization and with increasing horizontal coordination (Brandl, 2022).

Therefore, Traxler (2003) argues that “when actors face a high degree of interdependence of their goals, then coordinated action generally makes all of them better off than self-interested behavior” (page 195). In a similar vein, the coordination of wages and work conditions can also be achieved through horizontal relations (Nickell, 1997; Soskice, 1990; Traxler & Brandl, 2012). Coordination requires managing competing goals of internal efficacy of wages against the coordination necessary in collective bargaining among competing and/or cooperating firms. Coordination strengthens improved wage bargaining as firms assess, evaluate, deliberate, and coordinate fair and uniform wage structures. In consideration of new business entry, coordinated wage-setting allows for higher interdependence among industry participants, reduces friction in setting labor wages, and the overall “positive-sum nature of coordination” strengthens the occurrence and sustainability of coordination. Coordination may therefore lower inequality in wages across firms and may be more conducive to smaller firms that may be able to reduce wage-related turnover. With wages increasingly “compressed” across firms by skill and experience levels, smaller firms that are generally less competitive in attracting human capital may expect to build stickier and more embedded human capital (Calmfors & Driffill, 1988; Traxler & Brandl, 2012). Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3. Stronger coordination of wage-setting strengthens the positive relationship between the right of association and new firm establishments.

3 Data and methodology

3.1 Sample

Country-level data about the new business density are gathered on an annual basis by the World Bank and are available for the years 2005–2020. However, due to the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020, we use 2019 as the last year in our sample. Wage centralization, centralization of wage-setting, and coordination of wage-setting data have been obtained from the Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention, and Social Pacts (ICTWSS). This dataset is developed by the Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS) at the University of Amsterdam (Visser, 2019) and contains annual data for the past 60 years. The dataset was rebranded in 2021 as the OECD/AIAS ICTWSS database. With the World Bank development data on new business density being available from 2005 onwards, our analysis sample covers 44 countriesFootnote 1 representing 567 country-year observations from the years 2005 to 2019. From the World Bank’s world development indicators, we derived information about the country’s population size, gross domestic product (growth), unemployment rate, total natural resources rents, foreign direct investments (inflows and outflows), its position in the Human capital index, domestic absorption, consumption of household and government, capital stock, and total factor productivity. The latter variables are used as control variables in our models.

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Outcome variable

Our outcome variable is the World Bank’s new business density (NBD) measure. It reflects the number of newly registered corporations per calendar year, per 1000 individuals in the age range of 15–64. Importantly, the corporations are private, formal sector companies with limited liability. Thus, we focus on relatively large businesses of high quality (Oviedo et al., 2009). To deal with the time structure of the data, we use NBD in the next year as the dependent variable in our models.

3.2.2 Main explanatory variable: right of association (market sector)

The variable is measured as 3 = yes; 2 = yes, with minor restrictions (e.g., recognition procedures, workplace elections, thresholds); 1 = yes, with major restrictions (e.g., monopoly union, prior authorization, major groups excluded); and 0 = no (Visser, 2019). In our analyses, we treat this variable as a continuous measure, but we also conduct a robustness check in which we dichotomize the main explanatory variable.

3.2.3 Moderator variables

The descriptions of the moderator variables are reproduced below from Visser (2019)’s codebook.

Moderator variable 1: centralization of collective bargaining

This variable originates from the ICTWS database and is computed as [Level – ((rAEB × Art) + FAV + WSSA + OCG + OCT)/10], with Level being equal to 5 if wage bargaining predominantly takes place at the central or cross-industry level; 4 if wage bargaining intermediates or alternates between the central and industry level; 3 if wage bargaining predominantly takes place at the sector or industry level; 2 if wage bargaining intermediates or alternates between the sector and enterprise level; and 1if bargaining predominantly takes place at the company or enterprise level.

The incidence of additional enterprise bargaining is measured by rAEB, and this term is weighted by Art. Art represents that “the actions of the centre are frequently predicated on securing the consent of lower levels, and the autonomous action of lower levels is bounded by rules of delegation and scope for discretion ultimately controlled by successively higher levels”. The components of articulation are: 3 = articulated: additional enterprise bargaining on wages is recognized and takes place under the control of the “outside” union, i.e., the signatory or signatories of sector and company agreements come from the same organization(s) and are bound by the same rules; 2 = partially articulated: additional enterprise bargaining on wages takes place under control of the (non-union) works council; the signatory or signatories of sector and company agreements are bound by different rules and control of the “outside” union is partial; and 1 = disarticulated bargaining; additional enterprise bargaining on wages when it happens is, formally or informally, also conducted by non-union bodies and not answerable to or under control of the “outside” union.

Favorability (FAV) is the hierarchical relationship of agreements in a multi-level setting and guarantees that lower-level agreements can only deviate from higher-level agreements in ways that are favorable for workers. The variable is coded as: 3 = favorability is inversed, terms in lower level agreements take precedence; 2 = hierarchy between levels is undefined and a matter for the negotiating parties (not fixed in law); 1 = lower-level agreements must by law offer more favorable terms, but derogation is possible under defined conditions; and 0 = hierarchy between agreement levels is strictly applied and defined in law: lower-level agreements can only offer more favorable terms.

Wage-setting in sectoral agreements (WSSA) is coded as: 2 = sectoral agreements set the framework or define the default for enterprise bargaining; 1 = sectoral agreements define the minimum wage level (and minimum rate changes); and 0 = sectoral agreements define the minimum and actual levels (and rate changes) of wages working hours and minimum conditions on wages).

Opening clauses in sectoral collective agreements (OCG) are measured as: 2 = sectoral agreements contain opening clauses, allowing the renegotiation of contractual wages at enterprise level; 1 = sectoral agreements contain opening clauses, allowing the renegotiation of contractual non-wage issues (working time, schedules, etc.) at enterprise level; and 0 = agreements contain no opening clauses.

Finally, OCT is related to crisis-related, temporary opening clauses in collective agreement and is coded as: 1 = agreements (at any level) contain crisis-related opening clauses, defined as temporary changes, renegotiation, or suspension of contractual provisions under defined hardship conditions and 0 = agreements contain no opening clauses.

Moderator variable 2: coordination of wage-setting

Coordination of wage-setting is measured as: 5 = binding norms regarding maximum or minimum wage rates or wage increases issued as a result of (a) centralized bargaining by the central union and employers’ associations, with or without government involvement, or (b) unilateral government imposition of wage schedule/freeze, with or without prior consultation and negotiations with unions and/or employers’ associations; 4 = non-binding norms and/or guidelines (recommendations on maximum or minimum wage rates or wage increases) issued by (a) the government or government agency, and/or the central union and employers’ associations (together or alone), or (b) resulting from an extensive, regularized pattern setting coupled with high degree of union concentration and authority; 3 = procedural negotiation guidelines (recommendations on, for instance, wage demand formula relating to productivity or inflation) issued by (a) the government or governmental agency, and/or the central union and employers’ associations (together or alone), or (b) resulting from an extensive, regularized pattern setting coupled with high degree of union concentration and authority; 2 = some coordination of wage-setting, based on pattern setting by major companies, sectors, government wage policies in the public sector, judicial awards, or minimum wage policies; and 1 = fragmented wage bargaining, confined largely to individual firms or plants, no coordination.

3.2.4 Control variables

In our models, we control for various factors characterizing the institutional context and the economy of a country. From the ICTWSS dataset, to control for additional labor market institutions, we include variables capturing the right of collective bargaining in the market sector and the right to strike in the market sector. Using data from the World Bank indicators, we control for a country’s population size (logarithm), because the coordination costs of wage centralization and bargaining could be higher in countries with a larger population. Countries with larger populations are more likely to have a more diversified economy that, in turn, may drive variations in wage coordination across sectors (Driffill, 2006). The level of economic development is strongly associated with the strength of institutions, and therefore, we expect that countries with higher levels of economic development could have stronger wage centralization and wage coordination institutions and the necessary enforcement apparatus. Therefore, we control for gross domestic product (GDP, purchasing power parity; constant 2017 international $) and GDP growth (annual %).

Moreover, the unemployment rate (% of the total labor force) may increase labor supply and put downward pressure on wage coordination institutions. Higher unemployment is also associated with push-based entrepreneurship where considerations for wage-setting LMIs may not be a key consideration. The reliance on natural resources may lower the need for improving human capital and increase the focus on rent-seeking. Based on the classical resource curse argument, total natural resources rents (% of GDP) could lower the transition into entrepreneurship and reduce focus on developing richer human capital through stabilizing effects of wage centralization. Foreign direct investments (both inflows and outflows as % of GDP) are associated with increased entrepreneurial activity and may also infuse labor laws from multinational firms into the local economy (Eren et al., 2019). The human capital index measure from the World Bank is indicative of investments in the development of human capital. Countries with stronger human capital are likely to have stronger entrepreneurial human capital and may also provide robust support to wage coordination and centralization institutions by improving labor market inputs necessary to support fair wages.

The labor inputs can be substituted, to an extent, by capital and capital efficiency (Hirsch et al., 2014). We therefore control for domestic absorption (logarithm), consumption of household and government (logarithm), capital stock (purchasing power parity, in millions of 2017 US $), and total factor productivity (at constant national prices; 2017 = 1). To deal with the time structure of the data, we also include year dummies.

3.3 Methodology

Using panel regression, we use the right of association to explain new business density in the next year. We used a Hausman test to determine the suitability of the fixed-effects model versus the random-effects model. Based on the resulting p value of 0.134, we present the results of fixed-effects models in this study. To account for possible serial correlation and cross-sectional correlation, we additionally estimate the main model with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors in a robustness check.

The centralization of collective bargaining and the coordination of wage-setting are included as moderators in the model by using interaction terms. As discussed by Brandl (2022) and Traxler et al. (2001), and following our own argumentation, these moderators capture two different phenomena. Nevertheless, in our sample, the correlation between centralization and coordination is 0.633 (Table 2). Therefore, both moderators are included simultaneously in the regression model.

4 Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. In total, we have 567 observations from 44 different countries. On average, the number of newly established LLCs per 1000 individuals in the next year is 5.73 in the analyzed period. There is considerable cross-country variation though, from 0.07 in Japan (2007) to 39.04 in Cyprus (2006). The right of association is strong: The mean score of 2.817 results from 5, 94, to 468 country-year observations for scores 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Nevertheless, there is considerable variation in the centralization of collective bargaining and the coordination of wage-setting. Table 2 includes the pairwise correlations across all variables included in the fixed-effects regressions.

Table 3 presents the main regression results. In model (1), only the control variables are included in the model. Model (2) includes the main explanatory variable (the right of association). Model (3) additionally includes the moderators as the main effects, while model (4) is the most complete model with the interaction effects included. Hypothesis 1 proposes that the right of association in the market sector is positively associated with new business density. Models (2) and (3) provide direct evidence in favor of this hypothesis because the coefficients for the right of association are positive and statistically significant in both models. In model (2), the coefficient equals 0.183, suggesting that a 1-unit change in the right of association is associated with an increase of 20.1% in the number of new businesses. As the right of association is strong in most countries, we created a dummy variable equaling 1 in case the right of association in the market sector is as strong as possible (value 3) and 0 otherwise (values 0, 1, and 2). Due to the limited amount of within-country variation for the right of association, we again obtain a statistically significant coefficient of 0.183 in model 2 of this robustness check. This suggests that the main results reflect the difference between countries with the complete right of association and countries with a limited right of association.

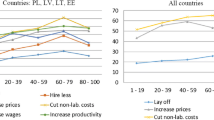

Hypothesis 2 proposes that the centralization of collective bargaining weakens the association between the right of association and new business density. In model (4), we indeed find a negative coefficient for the interaction between the right of association and the centralization of collective bargaining (− 0.445). That is, when the centralization of collective bargaining increases, the relationship between the right of association and new business density becomes negative. Figure 1 visualizes the interaction effect: Whereas for countries with weak centralization of collective bargaining (the solid line), the association between the right of association and new business density is positive, this relationship is negative for countries with strong centralization of bargaining (dashed line).

Plots visualizing the interaction effect of the right of association with the centralization of collective bargaining (left) and the coordination of wage-setting (right). The plots are based on the results of model (4) in Table 3

In line with Hypothesis 3, we expected a positive coefficient for the interaction term between the right of association and the coordination of wage-setting. The evidence for this hypothesis is, however, inconclusive. While the coefficient is indeed positive (0.146) in model (4), it is statistically insignificant. The visualization of the interaction term in Fig. 1 also shows that the relationship between the right of association and new business density is indeed rather similar for countries with strong or weak coordination of wage-setting.

In summary, in the main analyses, we find support for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2. However, we do not find support for Hypothesis 3. Due to potential serial correlation and cross-sectional correlation, we re-estimated the main model specification with Driscoll-Kraay standard errors. The results of this robustness check are reported in Table 4 and confirm the main results. That is, the right of association is positively associated with new business density in the next year, and this relationship is weaker when the centralization of collective bargaining is higher. However, coordination of wage-setting does not significantly affect the association between the right of association and new business entry.

5 Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we focused on the right of association, an underexplored labor market institution in the entrepreneurship literature that may affect new business entry. The results obtained using fixed-effects panel regressions show that the right of association does have a positive relationship with the new business density in the next year. Instead of being concerned about the potential burden of transacting through collective bargaining, prospective entrepreneurs may consider the presence of the right of association as a potential signal to employees that despite the potential risks of working in a new venture, the necessary security for the venture-specific human capital provided by them may develop over time.

However, centralized bargaining may dampen the expectations of prospective entrepreneurs, by reducing flexibility and putting added pressure to meet the wage requirements instituted by larger firms. Our empirical results show that stronger centralized bargaining negatively impacts the relationship between the right of association and new business density. The increasing pressures on new and smaller firms to meet the labor market obligations and the upward wage pressures could potentially deteriorate cash flows in smaller firms, and such forward-looking concerns may lower new firm undertakings.

We do not find support for a moderating role in the coordination of wage-setting on the relationship between the right of association and new business density. Wage coordination has been shown to improve the conditions of vulnerable workers (Weil, 2009), increase resilience in downturns (Weishaupt, 2021), and lower wage inequality (Vlandas, 2018), and past studies support that a coordinated bargaining system increases employment (Garnero, 2021). While our inconclusive evidence may be driven by the size of the analysis sample, the lack of effect may also be explained by that increasing wage coordination implies that firms are wage takers, reducing variation in interpreting the value of the right of association. Less coordinated wage coordination may allow ventures to more selectively incentivize employees. However, this potential explanation remains to be explored further in future research.

In aggregate, as discussed by Perone (2022), these findings echo Solow’s assertion that the labor market “is a social institution whose historicity and complexity cannot simply be characterized by the supply–demand model of labor markets (Solow, 2016)” (p. 501). Our results for Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2 support this narrative by suggesting that the advantages of the right of association could lower transaction costs for ventures and improve worker productivity and engagement, as long as centralized wage bargaining is low. These conditions reduce the frictions introduced by sclerotic labor markets, real wage rigidities, low labor mobility, adverse price variables, and standard macroeconomic features that may lead to higher structural unemployment rates because of the lack of labor market responsiveness to changes in both the supply and demand sides (Blanchard & Wolfers, 2000).

As such, our findings are informative for the much needed policy debate on how labor market institutions influence early-stage firms, especially given the recent change in the stance of the International Labor Organization on reducing efforts towards collective bargaining and increased focus on work flexibility (Evans & Spriggs, 2022). The COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing changes in preferences for work (e.g., quiet quitting or the Great Resignation) could be countervailing forces that may nevertheless increase preferences for collective bargaining. With workers seeking more flexibility and reduced work demands, labor market institutions are likely to be under increased pressure in the coming years, and smaller and younger firms may be particularly affected.

Although our research focuses on firm entry, a large body of work in entrepreneurship has focused on the human resource practices in young firms and the challenges they face in improving human capital. Cross-country variations in labor market institutions could play an important role in explaining the survival and growth of young firms (Jack et al., 2006). Relatedly, ventures in countries with stronger centralization and coordination may attract workers, and the imbibed human capital related to managing early-stage ventures could increase the overall entrepreneurial human capital. Future research could focus on the improvements in resources and capabilities from reduced concerns for the stability of human capital in ventures. Entrepreneurs in countries with stronger labor market institutions may face higher labor costs, but at the same time, they can improve focus on other important aspects of venturing, strengthen the internal climate and culture, and enhance venture-specific human capital investments.

Our findings are not without limitations. With the large number of studies using the ICTWSS data, we share that the coding for the main explanatory variable and moderator variables used in this study have their limitations (Visser, 2019). For example, the within-country variation in the main explanatory variable is rather limited in our analysis sample. Second, relatedly, our results were obtained in a panel for the year 2005–2019, due to the availability of new business registration data starting in 2005. While the panel covers countries in various stages of economic development and with variation in terms of the right of association, we note that many large within-country changes in the right of the association took place before 2005 in most countries. Third, our study focuses on the macro-level factors influencing entry. Though our estimates are robust at the country level, we call on future studies to focus on assessing individual-level factors in further understanding the micro-level mechanisms of how LMIs are taken into account by (potential) entrepreneurs.

Data Availability

All the data used in the study are publicly available (see Sect. 3).

Notes

The 44 countries are Argentina; Australia; Austria; Belgium; Bulgaria; Brazil; Canada; Switzerland; Chile; Costa Rica; Cyprus; Czechoslovakia; Germany; Denmark; Spain; Estonia; Finland; France; Great Britain; Greece; Croatia; Hungary; Ireland; Iceland; Israel; Italy; Japan; South Korea; Lithuania; Luxemburg; Latvia; Mexico; Malta; The Netherlands; Norway; New Zealand; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Serbia; Slovakia; Slovenia; Sweden; and Turkey.

References

Ahlquist, J. S. (2010). Building strategic capacity: The political underpinnings of coordinated wage bargaining. American Political Science Review, 104(1), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055409990384

Atkinson, J., & Storey, D. J. (2016). Employment, the small firm and the labour market. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315560205

Berg, J. (2015). Labour markets, institutions and inequality: Building just societies in the 21st century. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784712105

Berg, J., Kucera, D., Berg, J., & Kucera, D. (2008). In defence of labour market institutions. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230584204_2

Blanchard, O., & Wolfers, J. (2000). The role of shocks and institutions in the rise of European unemployment: The aggregate evidence. Economic Journal, 110(462), C1–C33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00518

Blanchflower, D. G., & Freeman, R. B. (1993). Did the Thatcher reforms change British labour performance? NBERWorking Paper, 4384.

Blien, U., Dauth, W., Schank, T., & Schnabel, C. (2013). The institutional context of an ‘empirical law’: The wage curve under different regimes of collective bargaining. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 51(1), 59–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2011.00883.x

Block, J. H., Fisch, C. O., Lau, J., Obschonka, M., & Presse, A. (2019). How do labor market institutions influence the preference to work in family firms? A multilevel analysis across 40 countries. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(6), 1067–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258718765163

Boeri, T. (2014). Two-tier bargaining. IZA Discussion Papers, 8358.

Braakmann, N., & Brandl, B. (2021). The performance effects of collective and individual bargaining: A comprehensive and granular analysis of the effects of different bargaining systems on company productivity. International Labour Review, 160(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12166

Brandl, B. (2022). Everything we do know (and don’t know) about collective bargaining: The Zeitgeist in the academic and political debate on the role and effects of collective bargaining. Economic and Industrial Democracy. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X221086018

Brandl, B., & Bechter, B. (2019). The hybridization of national collective bargaining systems: The impact of the economic crisis on the transformation of collective bargaining in the European Union. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 40(3), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X17748199

Burton, M. D., Fairlie, R. W., & Siegel, D. (2019). Introduction to a special issue on entrepreneurship and employment: Connecting labor market institutions, corporate demography, and human resource management practices. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 72(5), 1050–1064. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979391986640

Calmfors, L. (1993). Centralisation of wage bargaining and macroeconomic performance: A survey. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 131.

Calmfors, L., & Driffill, J. (1988). Bargaining structure, corporatism and macroeconomic performance. Economic Policy, 3(6), 13–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1344503

Campbell, B. A., Kryscynski, D., & Olson, D. M. (2017). Bridging strategic human capital and employee entrepreneurship research: A labor market frictions approach. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 11(3), 344–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1264

De Serres, A., & Murtin, F. (2014). Unemployment at risk: The policy determinants of labour market exposure to economic shocks. Economic Policy, 29(80), 603–637. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0327.12038

Dilli, S. (2021). The diversity of labor market institutions and entrepreneurship. Socio-Economic Review, 19(2), 511–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz027

Dimov, D. (2010). Nascent entrepreneurs and venture emergence: Opportunity confidence, human capital, and early planning. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1123–1153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00874.x

Doucouliagos, H., Freeman, R. B., & Laroche, P. (2017). The economics of trade unions: A study of a research field and its findings. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315713533

Driffill, J. (2006). The centralization of wage bargaining revisited: What have we learnt? Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(4), 731–756. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00660.x

Eren, O., Onda, M., & Unel, B. (2019). Effects of FDI on entrepreneurship: Evidence from Right-to-Work and non-Right-to-Work states. Labour Economics, 58(1), 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.04.008

Evans, J., & Spriggs, W. (2022). The great reversal: How an influential international organization changed its view on employment security, labor market flexibility, and collective bargaining. Journal of Law and Political Economy, 3(1), 172–197. https://doi.org/10.5070/LP63159036

Freeman, R. (2008). Labor market institutions around the world. In P. Blyton, N. Bacon, J. Fiorito, & E. Heery (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Industrial Relations (pp. 640–659). SAGE Publications.

Garnero, A. (2021). The impact of collective bargaining on employment and wage inequality: Evidence from a new taxonomy of bargaining systems. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 27(2), 185–202. https://doi.org/10.1177/095968012092077

Gimenez-Fernandez, E. M., Sandulli, F. D., & Bogers, M. (2020). Unpacking liabilities of newness and smallness in innovative start-ups: Investigating the differences in innovation performance between new and older small firms. Research Policy, 49(10). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104049

Golpe, A. A., Millán, J. M., & Román, C. (2008). Labour market institutions and entrepreneurship. In Congregado, E. (Eds), Measuring Entrepreneurship international studies in entrepreneurship, vol 16. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-72288-7_14

Grimshaw, D., Fagan, C., Hebson, G., & Tavora, I. (2017). A new labour market segmentation approach for analysing inequalities: Introduction and overview. In D. Grimshaw, C. Fagan, G. Hebson & I. Tavora (Eds), Making work more equal (pp. 1–32). Manchester University Press.

Henrekson, M. (2020). How labor market institutions affect job creation and productivity growth. IZA World of Labor, 38(1), 1–10.

Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2020). Measuring entrepreneurship: Do established metrics capture Schumpeterian entrepreneurship? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 44(4), 733–760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258719844500

Hirsch, B., Merkl, C., Müller, S., & Schnabel, C. (2014). Centralized vs. decentralized wage formation: The role of firms' production technology. IZA Discussion Papers, 8242.

Holmlund, B. (2014). What do labor market institutions do? Labour Economics, 30(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2014.06.007

Isidore, C. (2022). Despite union wins at Starbucks, Amazon and Apple, labor laws keep cards stacked against organizers. CNN [Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://edition.cnn.com/2022/09/05/business/union-organizing-efforts/index.html].

Jack, S., Hyman, J., & Osborne, F. (2006). Small entrepreneurial ventures culture, change and the impact on HRM: A critical review. Human Resource Management Review, 16(4), 456–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.08.003

Kenworthy, L. (2001). Wage-setting measures: A survey and assessment. World Politics, 54(1), 57–98. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2001.0023

Kochan, T. A., Katz, H. C., & Mckersie, R. B. (1988). The transformation of American industrial relations. Basic Books.

Marginson, P. (2015). Coordinated bargaining in Europe: From incremental corrosion to frontal assault?. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 21(2), 97–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680114530241

Marginson, P., Sisson, K., & Arrowsmith, J. (2003). Between decentralization and Europeanization: Sectoral bargaining in four countries and two sectors. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 9(2), 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/09596801030090020

Murtin, F., De Serres, A., & Hijzen, A. (2014). Unemployment and the coverage extension of collective wage agreements. European Economic Review, 71(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2014.06.010

Nickell, S. (1997). Unemployment and labor market rigidities: Europe versus North America. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 11(3), 55–74. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.11.3.55

Nickell, S., & Layard, R. (1999). Labor market institutions and economic performance. In O.C. Ashenfelter & D.Card, Handbook of labor economics (pp. 3029–3084). North Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4463(99)30037-7

Nyström, K., & Elvung, G. Z. (2014). New firms and labor market entrants: Is there a wage penalty for employment in new firms? Small Business Economics, 43(2), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9552-x

Oswald, A. J. (1979). Wage determination in an economy with many trade unions. Oxford Economic Papers, 31(3), 369–385.

Oviedo, A. M., Thomas, M. R., & Karakurum-Özdemir, K. (2009). Economic informality: Causes, costs, and policies - A literature survey. World Bank Working Paper, 167.

Peetz, D. (2021). The contradiction of international trends in freedom of association. Labour & Industry, 31(3), 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2021.1966291

Perone, G. (2022). The effect of labor market institutions and macroeconomic variables on aggregate unemployment in 1990–2019: Evidence from 22 European countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 31(2), 500–551. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtab074

Pries, M., & Rogerson, R. (2005). Hiring policies, labor market institutions, and labor market flows. Journal of Political Economy, 113(4), 811–839. https://doi.org/10.1086/430333

Rios-Avila, F. (2017). Unions and economic performance in developing countries: Case studies from Latin America. Ecos de Economía, 21(44), 4–36. https://doi.org/10.17230/ecos.2017.44.1

Scarpetta, S. (1996). Assessing the role of labour market policies and institutional settings on unemployment: A cross-country study. OECD Economic Studies, 26(1), 43–98.

Siepel, J., Cowling, M., & Coad, A. (2017). Non-founder human capital and the long-run growth and survival of high-tech ventures. Technovation, 59(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.09.001

Solow, R. M. (2016). Resources and economic growth. American Economist, 61(1), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/056943451562709

Soskice, D. (1990). Wage determination: The changing role of institutions in advanced industrialized countries. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 6(4), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/6.4.36

Traxler, F. (2003). Coordinated bargaining: A stocktaking of its preconditions, practices and performance. Industrial Relations Journal, 34(3), 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2338.00268

Traxler, F., & Brandl, B. (2012). Collective bargaining, inter-sectoral heterogeneity and competitiveness: A cross-national comparison of macroeconomic performance. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(1), 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2010.00804.x

Traxler, F., Blaschke, S., & Kittel, B. (2001). National labour relations in internationalized markets: A comparative study of institutions, change, and performance. Oxford University Press.

Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., Frese, M., & Rosenbusch, N. (2011). Human capital and entrepreneurial success: A meta-analytical review. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.09.004

Visser, J. (2019). ICTWSS data base, version 6.1. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies.

Vlandas, T. (2018). Coordination, inclusiveness and wage inequality between median-and bottom-income workers. Comparative European Politics, 16(3), 482–510. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2016.25

Weil, D. (2009). Rethinking the regulation of vulnerable work in the USA: A sector-based approach. Journal of Industrial Relations, 51(3), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185609104842

Weishaupt, J. T. (2021). German labour market resilience in times of crisis: Revealing coordination mechanisms in the social market economy. German Politics, 30(3). https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2021.1887852

Windmuller, J. P. (1987). Comparative study of methods and practices. In J. P. Windmuller (Ed.), Collective bargaining in industrialized market economies: A reappraisal (pp. 3–161). International Labour Office.

Zagelmeyer, S. (2005). The employer's perspective on collective bargaining centralization: An analytical framework. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(9), 1623–1639. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190500239150

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, P.C., Rietveld, C.A. Right of association and new business entry: country-level evidence from the market sector. Small Bus Econ 61, 1161–1177 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00727-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00727-1

Keywords

- Labor market institutions

- New business registrations

- Right of association

- Wage centralization

- Wage coordination