Abstract

Our study identifies regional traits associated with small business viability, paying particular attention to bank lending to minority-owned firms. Although creditworthy minority business enterprises (MBEs) have less access to bank financing than similar White-owned firms, they have increased their nationwide employee numbers substantially since 2002, more so indeed than White-owned firms. The discouraged borrower incidence among creditworthy MBEs, nonetheless, is quite high. Given their limited access to financing, the dynamism displayed by these firms is surprising. To link regional characteristics to bank lending policies, local economic well-being measures and racial intolerance levels are used to identify areas where banks participate in Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) agreements, a proxy for their willingness to disregard owner race and firm geographic location when financing firms. We find that regional prosperity is positively linked to CRA agreement presence, while a legacy of institutionalized racism is negatively linked. We next explore whether the presence of local CRA agreements is linked to relatively fewer discouraged small business borrowers. The incidence of creditworthy borrowers discouraged from seeking bank financing drops significantly when CRA agreements are present locally.

Plain English Summary

Access to bank financing, a key growth determinant for Black and Latino-owned firms, is most accessible in prosperous metro areas with large minority populations and much less so in those with an entrenched heritage of institutionalized racism. Minority-owned firms doubled their nationwide paid employee numbers from 2002 to 2018, while White-owned firms generated only a 5% increase. Increased bank lending facilitated their rapid growth. Our objective is to identify regional traits associated with small business viability, paying particular attention to the ability of minority-owned firms to obtain bank financing. To link regional characteristics to bank policies, local economic well-being measures and racial intolerance levels are used to identify areas where banks are inclined to employ fair lending practices. Our fair lending proxy measure is the willingness of banks to participate in CRA agreements. Local customs and traditions shape bank acceptance or rejection of these agreements. Most banks in metro areas where institutional racism is deeply embedded do not participate in CRA agreements, while in prosperous areas with large minority populations, most do. The incidence of creditworthy borrowers discouraged from seeking bank financing drops significantly where CRA agreements are present locally.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Our objective is to identify the impacts of regional characteristics on small business viability. We begin by analyzing the expanding access to bank loans that minority business enterprises (MBEs) have experienced in recent decades and the contexts in which gains have occurred. Our focus on banks is motivated by the fact that restricted access to financing retards minority business viability (Fairlie et al., 2022). Fairlie and Robb (2008) identified startup capitalization as the strongest predictor of subsequent small-business survival, profitability, and growth. The odds of young firms prospering are particularly impacted by their initial capitalization levels. Those receiving bank loans are the larger-scale, more successful businesses (Bates, 1997; Bates et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2022).

A related determinant of small business outcomes is the metropolitan area in which firms are located. Like small firms generally, minority business performance is shaped by local customs, traditions, values, and attitudes, sometimes positively and sometimes negatively (Tavassoli et al., 2021). Regarding regions with a history of institutionalized racial discrimination, norms, values, and traditions from earlier times powerfully explain behavioral variations across these same areas in the present day (Chatterji & Seamans, 2012; Fairlie et al., 2022). We proceed by delineating metropolitan areas amenable to supporting viable young firms generally and minority-owned firms specifically from those apt to retard their progress. Identifiable regional traits, we find, effectively delineate those providing supportive environs from those where young firm viability is retarded.

Being adequately capitalized is essential for young businesses (Fairlie & Robb, 2008). Greater capitalization serves as a buffer protecting young ventures from the liabilities of newness. Under-capitalization limits their ability to withstand unfavorable shocks and to undertake corrective actions. More capitalization buys time while the owner learns how to run the business. Lacking an adequate buffer, poorly capitalized firms often shut down in difficult periods (Cooper et al., 1994). Beyond startup, a firm’s ability to qualify for financing is an important determinant of its ultimate success or failure. Sufficient capital is linked positively to firm viability early on, and growth typically requires additional funds (Fairlie & Robb, 2008, 2010).

We proceed by linking small business viability to select regional characteristics. We utilize the presence of Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) agreements as a proxy identifying metro areas where banks are amenable to financing viable young firms irrespective of owner race/ethnicity and/or their geographic location. The fact that banks involved in CRA agreements are active lenders to minority-owned businesses is well established (Avery, Bostic, & Canner, 2000; Bates, 2022; Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2017), as is the shifting racial composition of small-business bank lending nationwide from Whites to MBEs (Bostic & Lee, 2017). Our findings indicate that banks in prosperous metro areas with large minority populations are significantly more likely than others to participate in CRA agreements. Those in economically depressed areas having a heritage of institutional racism are less likely to embrace the fair lending practices inherent in CRA agreements. Our findings also indicate that young small businesses operating in metro areas with active CRA agreements in place are less likely to be discouraged borrowers than those in areas lacking such agreements.

2 Bank financing matters

Owners of viable firms have adequate financing to operate at an efficient scale and to exploit business opportunities when they arise. Regarding access to bank financing, multiple studies have shown that non-minority White applicants are more likely to qualify for loans than equally creditworthy minority business owners (Bates, 2022; Bates & Robb, 2015; Mitchell & Pierce, 2011). Blanchard et al. (2008), for example, analyzed Federal Reserve data and found substantial discrimination against Black- and Hispanic-owned businesses in loan-application approval rates. Bone et al. (2014) documented blatant discrimination targeting Black and Latino firm owners at the loan inquiry stage. Among recipients of bank loans, furthermore, they received smaller loans and paid higher interest rates than equivalent White-owned firms (Bates, 1991; Bates & Robb, 2016; Cavalluzzo & Wolken, 2005; Fairlie et al., 2022). Regarding the possible discriminatory treatment of Asian–American business owners applying for bank loans, findings have been inconclusive.

Although studies frequently document discriminatory banker treatment of minority-owned businesses, few probe why discrimination occurs. Banks’ denying loans to creditworthy minority borrowers strikes economists as irrational, suggesting rejection of profit maximization as their guiding objective (Becker, 1993). Such discrimination, however, is not always inconsistent with profit maximization. Becker ignores the regional context in which banks are embedded. The dominant values, traditions, and attitudes prevalent locally constitute the crux of the matter for both mainstream sociologists and institutionalist scholars. Regional embeddedness in this instance refers to prevailing societal perceptions that certain bank transactions are inappropriate in the context of socially constructed local systems of norms, values, and beliefs. Banker actions lacking local legitimacy are offensive, quite possibly driving away customers. Minorities, for example, may be expected to reside in certain neighborhoods, work in certain jobs, and operate in certain kinds of businesses. While African–American ownership of barbeque restaurants may be supported by prevailing norms, their ownership of high-end stores in upscale neighborhoods may violate local customs. Banker refusal to finance such offensive, inappropriate businesses irrespective of their credit worthiness may be viewed as perfectly legitimate locally and thus desirable and proper. Adherence to these norms perpetuates entrenched discrimination toward minority-owned small businesses in terms of lending (Jackson et al., 2018).

Key factors shaping the decision of firm owners to apply for bank loans include both their creditworthiness and their geographic location. Among White and Black owners with below-median credit scores, rates of bank loan application do not differ, but above-median Black owners needing financing are much less likely to apply for bank financing than equally creditworthy White owners. “Black business owners whose credit scores are above the 75th percentile were about three times more likely not to apply for loans because of fear of rejection than White business owners” (Fairlie, et al., 2022, p. 2389). They were discouraged borrowers. Focusing on firm location, they investigated whether this fear of loan denial might be more pronounced in areas where historically high levels of racial discrimination prevailed. Local areas with a heritage of institutionalized racism, they found, “have much higher levels of the fear of denial among black entrepreneurs relative to white entrepreneurs” (Fairlie, et al, 2022, p. 2393). Chatterji and Seamans (2012) found these same effects were magnified in states with laws banning interracial marriage still on the books in 1967, suggesting institutional discrimination’s active role as an enduring barrier to bank loan access for minority owners of businesses.

Fairlie et al. (2022) also investigated whether contemporary measures of racial intolerance might explain this pronounced discouraged-borrower phenomenon. To identify such areas, they used rates of interracial marriage as a proxy measure of regional racial intolerance and found that less African American fear of loan application denial and unmet capital needs prevailed in metro areas with high interracial marriage rates. Where racial intolerance was prominent both historically and in the present day, in contrast, highly creditworthy Black-owned businesses in need of financing often did not apply for loans because they expected bankers to deny their applications (Fairlie, et al., 2022). Stated differently, place matters: individual metropolitan areas have distinct customs, traditions, values, and beliefs, traits we refer to as regional personality traits (below). America’s regional variance in personalities, thusly defined, is wide.

3 Place matters

3.1 Personality traits of economically vibrant cities

For many of America’s cities, skill-intensive services industries are a major base industry sector, exporting their products regionally, nationally, and internationally. Talent-dependent businesses like professional, technical, financial, informational, managerial, medical, and educational services are reshaping the city and regional economies as the local economic base has shifted away from previously dominant industries like manufacturing. Areas like downtown San Francisco, Chicago, Atlanta, and midtown Manhattan have benefitted from these trends, and they share certain traits, including industry density and diversity, compactness, and walkability, traits recognized as causal factors driving service-sector growth (Malizia & Chen, 2019). Armington and Acs (2002) found that local traits associated with high business startup rates also included a large proportion of college-graduate residents and regional prosperity, proxied by high regional income and population growth.

Firm birth rates vary tremendously among America’s metro areas, and certain causal connections between robust firm creation and industry density and diversity, agglomeration externalities, and the like have been documented. A highly educated workforce provides the absorptive capacity to understand knowledge spillovers, comprehend their value, and commercialize them, which often entails creating new businesses (Qian & Acs, 2013). Diversity of people facilitates knowledge-spillover-inspired entrepreneurship. The same piece of knowledge may be interpreted and valued in varying and diverse ways by people with differing backgrounds and perspectives. Such creative interpretation is associated with local population diversity in multiple factors, including educational background, income, occupational specialization, gender, race, and ethnicity, among others (Qian, 2018). “The more different kinds of people evaluate any given idea, the higher will be the probability that one of these persons will arrive at the conclusion that she wants to commercially exploit it” (Audretsch et al., 2010, p. 58).

An important trait explaining quality business startups is local openness to new ideas and experiences. Using quantitative measures of openness—imagination, curiosity, wide scope of interests, unconventionality, and others—as explanatory variables, Tavassoli et al. (2021) found that greater local openness is highly correlated with quality entrepreneurship. Interaction between local openness and a favorable city structural environment, furthermore, strengthens the openness effect on quality entrepreneurship (Tavassoli, et al., 2021). Highly educated individuals open to new ideas tend to avoid living in racially intolerant low-and-no-growth regions resistant to change. They gravitate instead toward economically vibrant regions, thus creating tendencies for the curious, imaginative, and unconventional of the world to cluster where their openness is valued and their skills are in demand. Thus, the personality of a metro area directly impacts its economic vibrancy.

Judged by standard prosperity measures, very large metro areas are winning America’s best-personality contest. The 53 largest generated 73% of the nation’s employment gains between 2010 and 2016 (Muro & Whiton, 2018). Regarding annual growth in median employee earnings, 3.0% growth described America’s midsize metro areas from 2008 to 2018, versus 6.5% for the largest (Berube, 2020).

3.2 Traits of vibrant metropolitan areas

Austin, Denver, and Charlotte typify economically vibrant areas where employment in a particularly dynamic sector, IT/digital services, has clustered (Muro & Whiton, 2018). Statistics describing central-city resident wellbeing suggest the benefits of regional vibrancy are widely shared. Adult labor-force participation rates are markedly higher than corresponding rates nationwide, and unemployment rates are much lower (Table 1). Median household incomes are well above the $53,700 nationwide figure.Footnote 1 Resident demographic makeup is noteworthy: Austin, Denver, and Charlotte collectively had 2.42 million central-city residents in 2017, of which 53.2% were Black or Latino and 38.8% were White (U.S. Bureau of the Census American Factfinder, 2019). In the nation’s economically dynamic very large cities and metro areas, minorities increasingly constitute a majority of the residents.

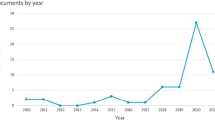

How exactly do MBEs fit into this vibrant-city growth story? An examination of nationwide paid-employee numbers indicates that minority-owned firms doubled their paid-employee headcount between 2002 and 2018, creating 4.7 million new jobs, while non-minority White-owned firms increased theirs by 2.8 million (Table 2). Over 60% of those new jobs came from minority firms employing 20 + workers, firms owned predominantly by college graduates (Bates, 2022).

4 Interest in small-business ownership among African Americans and Latinos

Where did these college-graduate owners come from? Black college graduates traditionally concentrated in teaching and preaching occupations (Bates, 1973). Rising Black political power was one factor altering this longstanding status quo. Atlanta’s preferential procurement program, for example, “attracted Blacks out of corporate-sector management, administrative, and executive positions and into entrepreneurial careers” (Boston, 1999, p. 14). Similar dynamics in many other cities drew college-educated minorities into small-business ownership as well (Handy & Swinton, 1984). Incentive structures traditionally making entrepreneurial pursuits poor career choices for college-graduate minorities were evolving, and young adults altered their behavior accordingly (Bates, 1993).

Coinciding with improving entrepreneurial prospects came surging college admissions and major shifts in fields of concentration: business administration replaced education as the most popular undergraduate major (Bates et al., 2018). Bachelor’s degrees in business awarded to Blacks and Latinos rose nationwide from 11,956 in 1976 to 86,229 in 2018 (Carter & Wilson, 1992; U.S. Department of Education, 2019). MBA degrees rose phenomenally as well (Table 3). Their changing fields of concentration coincided with a growing interest in entrepreneurship as an occupational choice (Kollinger & Minetti, 2006). These increases in human capital facilitated transformational changes in the scope of America’s Black and Latino business communities. Bachelor’s and MBA degrees in business fields provided greater access to employment in private enterprises, and the expertise, resources, and network connections thus gained facilitated creation of minority-owned small firms capable of competing in mainstream product markets. High-growth small-business fields are those into which college-graduate minorities were most attracted (Bates, 2022).

Consequences of highly educated and experienced minorities pursuing the entrepreneurial path are apparent in the caliber of Black and Latino owners seeking financing for their firms. Among young small businesses applying for bank loans nationwide, non-minority Whites lagged behind African Americans and Latinos in terms of their incidence of college graduates. Regarding years of work experience in the specific industry niche in which the applicant’s firm was operating, furthermore, Black loan applicants had 14.8 years, and Latinos had 14.0 years, while non-minority Whites had 13.9 years of relevant hands-on work experience (Bates, et al., 2022).

5 Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) agreements

5.1 Origins

Banks, according to CRA provisions, have affirmative obligations to meet the credit needs of all local communities from which they receive deposits (Barr, 2005). Yet for over a decade after its passage in 1977, the CRA had no discernable impact on the accessibility of banking services to minorities. Inspiring rhetoric notwithstanding, status-quo lending practices remained. Regulatory authorities took few steps to define, much less enforce its provisions (Bernanke, 2007). By ignoring redlined neighborhoods for many decades, banks had created an informational black hole: property appraisals were rare and unreliable. Many residents and small businesses lacked credit ratings (Berry & Romero, 2017). Because minimal information on loan-applicant creditworthiness was available in redlined areas, evaluating applicant risk was time-consuming and costly (Bernanke, 2007). Most banks chose not to bear those costs. After being repeatedly prodded by external forces, however, certain very large banks began to address those deficiencies (Immergluck, 2004).

By 1989, activist-group challenges to discriminatory bank practices had generated sympathetic media attention. Media coverage of the offending practices heightened Congressional concern, which resulted in legislation strengthening CRA requirements (Bates & Robb, 2015; Immergluck, 2004). Because of these push factors, the costs to banks of ignoring their CRA obligations rose. Very large banks in particular began interactions with activists, and CRA agreements often emerged whereby banks agreed to adopt affirmative policies expanding lending to minority applicants and neighborhoods (Barr, 2005; Immergluck, 2004). Community activism pressured regulators to start considering bank participation in CRA agreements when assessing their CRA performance (Immergluck, 2004, p. 167). The ensuing proliferation of CRA agreements was an essential catalyst for providing minority customers with expanded banking services (Bernanke, 2007).

CRA agreements are currently in force in most metropolitan areas, and the evidence indicates they are effective. The presence of a CRA agreement in a metropolitan area encouraged Blacks and Latinos to submit more home mortgage loan applications to banks compared to residents in areas lacking agreements (Casey et al., 2011). Banks entering into CRA agreements typically inaugurated special programs to increase their lending to minority clients (Avery et al., 2000; Schill & Wachter, 1995). To measure the impacts of these agreements, the Fed surveyed large banks, and among the very largest, 89% offered special CRA lending programs, 27 of which focused on small-business lending (Avery et al., 2000). Noteworthy were the 42% of large banks citing “Identifies profitable new markets” as a benefit of their participation. Spatially, firms in minority neighborhoods experienced higher rates of loan-application approval from large banks (not small banks), compared to those in other neighborhoods (Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2017). Similarly, firms located in CRA-eligible census tracts were more likely to attract bank financing than firms in adjoining ineligible tracts (Kim et al., 2021). Abundant evidence suggests that CRA agreements worked as intended: minorities applied for loans more frequently and with greater success (Avery et al., 2000; Bates & Robb, 2015; Bostic & Robinson, 2005; Casey, et al., 2011; Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2017).

5.2 CRA agreements, banker intent, and the appeal of cultivating MBE customers

Among small-business loan applicants, information asymmetries complicate banker attempts to determine their creditworthiness. Bankers have imperfect information about entrepreneurs’ actual expertise, and they are vulnerable to opportunistic defaults rooted in moral-hazard issues, factors encouraging them to require substantial collateral from borrowers (Aghion & Bolton, 1997). Outright racial discrimination on the part of bank loan officers is another complicating factor (Bone, et al., 2014; U.S. Department of Justice, 2012). Regarding owners of firms seeking financing, bankers compensate themselves for the risks inherent in serving their financing needs. As perceived risks rise, loan size is reduced, thus providing more dollars of collateral per loan dollar. Similarly, interest rates are boosted to compensate the lending bank for the risks it assumes.

Sellers’ inferences about racial differences in borrower reservation prices may encourage bankers to charge minority customers higher prices for the same products they sell to otherwise identical White customers (Bates et al., 2018; Salop & Stiglitz, 1977). Audit studies demonstrate that reservation-price differentials result in firms charging minority customers higher prices than Whites for identical products (Ayers & Siegelman, 1995; Yinger, 1998). Stated differently, banks seek to profit from the weaknesses they perceive in the bargaining position of minority customers seeking financing. Existing evidence indicates that minority business owners receive smaller loans and are charged higher loan interest rates than similarly creditworthy White owners (Bates, 1991; Bates & Robb, 2016; Fairlie et al., 2022). The bottom line is that irrespective of pressures to treat minority customers fairly, bankers seeking profitable new markets may be attracted to minority-owned firms simply by the prospect of high financial returns.

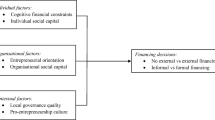

Among banks, early movers entering into CRA agreements were influenced originally by pressures imposed by external forces, push factors (Bates & Robb, 2015; Bernanke, 2007; Immergluck, 2004). While accepting their relevance, our analysis focuses instead on pull factors, characteristics of metro areas motivating banks to accept or reject CRA agreements. While large banks accepting CRA agreements sought new lending opportunities by instituting special programs to expand their minority customer base (Avery et al., 2000), those seeking to avoid minority clients lacked this incentive. We proceed by testing the hypothesis that banks with CRA agreements were drawn in by pull factors—profitable opportunities—while those averse to dealing with potential minority customers were not. Stated differently, we hypothesize that (1) greater local prosperity predicts a higher likelihood of CRA agreements, while (2) locally prevalent racial animosity predicts less likelihood of CRA agreements. We proceed by introducing local economic well-being measures identifying metro areas where banks may seek to expand their services. Next, we identify measures of the degree of competitiveness in the local banking market, the likelihood that racial animosity is prevalent, and test whether these local traits delineate geographic areas where banks participated in CRA agreements versus those with no agreements.

-

Hypothesis one: Banks are inclined to enter CRA agreements in metro areas with relatively low unemployment rates. Low unemployment levels are observed consistently in metro areas with economically vibrant economies.

-

Hypothesis two: The percentage of the local households subsisting on poverty-level incomes is typically higher in regions with laggard economies, indicating an inverse relationship between the incidence of poverty and bank willingness to embrace CRA agreements. Local economic vibrancy, in fact, may co-exist with high poverty rates, as booming economies may generate numerous low-wage service jobs and hence, working poverty. Whatever the cause, a higher poverty incidence locally suggests less likelihood of banks participating in CRA agreements.

-

Hypothesis three: In metro areas where the minority share of the population is large, expansion in underserved minority markets holds the potential for banks to reap substantial gains in customer numbers and thus, the possibility of earning attractive financial returns. Thus, we expect a positive relationship between the minority percentage of the local population and the likelihood of banks participating in CRA agreements.

-

Hypothesis four: Overt racial discrimination was widely prevalent historically in states where anti-miscegenation laws prevailed. Although laws forbidding people of different races to marry were abolished decades ago, lingering racist attitudes suggest that banks in states where such laws existed in 1967 are less likely to enter into CRA agreements than banks operating elsewhere (Chatterji & Seamans, 2012; Fairlie et al., 2022).

We proceed by using logistic regression analysis to delineate firms in geographic areas where CRA agreements are in place (dependent variable = 1) from those lacking agreements (dependent variable = 0). These agreements most often focus on banking practices in one metro area. Our unit of observation is the individual firm, and the explanatory variables are traits of the areas in which each firm operates—the unemployment rate, poverty incidence, percent of minority residents, competitiveness in the local banking market, and prevalence of lingering racist attitudes.Footnote 2 Using individual firms as our unit of observation has the advantage of weighting firm geographic locations such that metro areas with numerous firms shape our econometric results more heavily than areas with few.

Our data source, the Kauffman Firm Survey (KFS), includes small firms started in 2004, and firms subsequently surveyed annually through year-end 2011. We use weighted KFS data, making the data broadly representative of young small firms nationwide. As hypothesized, our regression findings indicate that lower metro-area poverty and unemployment rates, other factors being equal, predict a greater likelihood that banks with CRA agreements are prevalent locally (Table 4). More economically vibrant regional economies are positively associated with an enhanced likelihood that CRA agreements are present. High prevailing local rates of poverty and unemployment, in contrast, may cause banks to view metro areas as poor prospects. A higher proportion of minority residents within a metro area, furthermore, is associated with a greater likelihood that local banks have CRA agreements. Numbers of bank branches locally are a proxy measure of the degree of competitiveness (Cavalluzzo & Wolkin, 2005). Our findings suggest that greater competitiveness is positively associated with an enhanced likelihood of banks participating in CRA agreements. Regarding metro areas in states where anti-miscegenation laws existed in 1967, our findings are quite clear-cut: more than any other factor, the past existence of state anti-miscegenation laws powerfully predicts the present-day absence of CRA agreements (Table 4). “The past is never dead” observed Mississippi Nobel laureate William Faulkner. “It’s not even passed” (1975, p. 80). The bottom line is that pull factors matter, but not as much as Faulkner’s lingering racist heritage factor.

Envision a two-by-two matrix classifying metro areas on the basis of the presence/absence of past anti-miscegenation laws and the presence/absence of present-day CRA agreements. Examining contents of two of the matrix cells, Table 5 describes traits of metro areas with both a heritage of racist laws and no CRA agreements versus those with CRA agreements in place and no such heritage. Also included are characteristics of their respective local business owners and their firms. Differences in local prosperity are stark: among those with CRA agreements in place, the percentage of local residents living in the poverty line is 7.8%, versus 10.9% in metro areas devoid of such agreements. Percentages of unemployed local residents were higher in the metro areas lacking CRA agreements as well, and their local banking markets were less competitive than those with active CRA agreements.

Economically vibrant metro areas typically have a high incidence of college-graduate residents, a trait characteristic of local business owners as well, and Table 5 highlights differentials among local owners of small firms: 49.5% of them were college graduates in areas lacking CRA agreements, versus 59.6% in areas with prevailing agreements. Regarding traits of the local businesses, those in metro areas with CRA agreements in place reported average annual sales revenues over one-third higher than their counterparts in areas lacking agreements, and corresponding differentials in sales per employee were large as well (Table 5). In states with an institutionalized racist heritage, the portrait of metro areas lacking CRA agreements is one of greater poverty and unemployment and relatively fewer college-graduate business owners running smaller, more labor-intensive firms, compared to those with CRA agreements and no such legal heritage.

The bottom line is that America’s more economically vibrant metro areas are the ones most often embracing CRA agreements. A more vibrant, growing local community of minority businesses is the probable consequence, which, in turn, reinforces regional vibrancy. In Austin, Charlotte, and Denver collectively, for example, Black- and Latino-owned business-services firms with paid employees have expanded in number three times faster than firms in this industry subgroup nationwide. CRA agreements are operative in each of these metro areas. The nation’s less vibrant metro areas lacking CRA agreements would benefit from prospering local minority-owned businesses, but the lower propensity of their banks to finance these firms reduces their potential to boost local economic development.

6 Discouraged firms: businesses needing credit but not applying for financing

CRA agreement presence is an indirect measure of commercial bank willingness to finance creditworthy small businesses irrespective of owner race/ethnicity and firm location. Our final task entails testing whether CRA agreement presence locally actually impacts the borrowing behavior of small firms needing credit. Our dependent variable, discouraged borrower, identifies those firms needing credit but failing to apply for bank financing because they expect their loan applications to be rejected. Fairlie et al. (2022) have demonstrated that a particularly high incidence of discouraged borrowers characterizes Black-owned firms with strong credit ratings.

Using logistic regression analysis to delineate discouraged small business borrowers (dependent variable = 1) from others (dependent variable = 0), we analyzed KFS data describing young firms located in metropolitan areas nationwide. Included in the analysis are small firms with non-minority White, Black, and Latino owners. Explanatory variables include measures of the business owner’s human capital, race/ethnicity, and personal net worth; firm traits include credit rating and firm size measures; regional traits include the presence locally of a CRA agreement, metro area household poverty rates, and firm location in minority neighborhoods. We proceed by testing the hypothesis that CRA agreement presence reduces the incidence of discouraged small business borrowers within metro areas, especially Black and Latino owner borrowers.

As hypothesized, our regression-analysis findings indicate that the local presence of CRA agreements predicts a pronounced reduction in the incidence of discouraged borrowers among Black, Latino, and White business owners. Our unexpected finding is that these agreements positively impact not only Black and Latino owners, but White owners as well. The firms/owners least likely to be discouraged borrowers have high credit ratings, personal owner wealth of at least $250,000, and a college degree. The full range of owner, firm, and regional traits associated with a highly discouraged borrower presence includes low owner wealth and firm credit ratings, fewer college graduates, absence of CRA agreements locally, and being a Black or Latino business owner in a metro area lacking CRA agreements. Importantly, neither a firm located in a minority neighborhood nor one where poverty rates are high have discernable impacts on discouraged borrower likelihood. Thus, the owner of a firm located in a poor minority neighborhood is no more likely to be a discouraged borrower than the owner of a firm operating in an affluent White neighborhood, other factors being equal. This finding is consistent with past evidence indicting that neighborhood redlining by bankers is no longer detectable as far as small business lending spatial patterns are concerned (Bates & Robb, 2016).

Taken literally, our regression findings summarized in Table 6 suggest that Black and Latino owners needing financing and operating firms in metro areas where CRA agreements are in place are 79% less likely to be discouraged borrowers than an otherwise identical firms/owners in metro areas lacking CRA agreements. Because the CRA agreement characteristic is not truly an exogenous variable, however, an insightful interpretation of its real significance requires a closer examination of the evidence. We know from Table 4’s logistic regression findings that prevailing CRA agreements are found disproportionately in America’s metro areas where unemployment and household poverty rates are relatively low, the percentage of minority residents is relatively high, the banking sector is highly competitive, and a heritage of racist laws is absent. Table 6 regression findings clearly imply that in such metro areas, banker willingness to finance creditworthy small businesses generally is greater than in metro areas of less banker competition, more poverty and unemployment, and the like. Although these must be viewed as tentative findings, they are consistent with our belief that bankers in twenty-first-century America are, on balance, more often pulled into CRA agreements by the lure of attractive financial returns than pushed into CRA agreements by external forces.

7 Policy implications

Job creation provides an important rationale for promoting MBEs because the employment opportunities these firms create are often captured by those possessing few attractive labor-market options. MBEs are far more concentrated in urban minority neighborhoods than White-owned businesses, and they actively hire workers in those communities, more so than non-minority White firms of similar size (Bates et al., 2022; Boston, 1999; Simms & Allen, 1997). MBEs, furthermore, hire a predominantly minority workforce (Bates, 2006). “Survey results indicate that 82% of the employees in Black-owned businesses located within the City of Atlanta are Black” (Boston, 1999, p. 50). Young small firms often draw employees from family-and-friends-based networks, which contributes to the pronounced differences in the racial composition typifying the employees of minority versus White-owned firms. “Even among businesses physically located within minority communities, the majority of workers employed by non-minority-owned small firms are White” (Bates, 1994, p. 113).

Additional indirect effects of viable minority businesses are noteworthy as well. Successful entrepreneurs building companies in minority communities, notes Michael Porter, “provide powerful role models and motivation for pursuing education, training, and work.” Such development, furthermore, “conserves public resources, benefits local property owners, and reduces the challenges facing city government” (Porter, 2016, p. 107).

8 Concluding remarks

We have not summarized the applicable literature analyzing linkages between regional characteristics and the viability of African American and Latino-owned businesses because there is none. This study represents our attempt to initiate the type of analysis that may ultimately generate such a literature. In hindsight, the strong latent desire of African and Latino Americans to pursue entrepreneurial career paths is now apparent (Reynolds et al., 2004). In the process, a minority business community of small neighborhood firms serving minority household clients has transitioned into one dominated by firms competing in mainstream markets (Bates, 2022). An easing of the barriers traditionally constraining the size and scope of America’s minority-owned businesses has made this ongoing transition a reality. Progress has been uneven, rapid in some regions of the nation, and slow in others. The objective of this study is to understand key factors shaping these variations.

The emergence of large-scale minority firms selling products to mainstream clients has been greatly facilitated by their expanding access to bank financing. Most of America’s Black and Latino-owned employer firms operate in urban minority neighborhoods, areas where relatively high household poverty and under-employment rates are the norm. Among young Black business owners applying for bank loans nationwide, 63.8% of them ran firms located in minority neighborhoods. Household poverty rates were higher in zip codes where those applicants are located—12.7% among Black loan applicants and 9.0% among non-minority White applicants (Bates, et al., 2022). Among those receiving bank loans, 60.8% were located in minority neighborhoods. Consistent with the intent of the 1977 CRA, bank financing now flows into neighborhoods characterized by above-average rates of household poverty, underemployment, and low labor force participation rates.

In a very real sense, our study is tiptoeing around a broader set of issues about America’s future as a multi-racial society, one in which non-minority Whites are a declining portion of the population. Provocative big questions seek answers. Our findings suggest that relatively few college-graduate minority owners are starting firms in America’s racially intolerant regions. Are America’s economically vibrant, knowledge-spillover-prone metro areas exhibiting above-average openness attracting minority college-graduate new residents disproportionately? Is there an identifiable causal link between regional growth, prosperity, openness, and the presence of policies seeking a level playing field so that minorities may someday be as likely to access opportunities as equally qualified non-minority Whites? Do prosperous regions moving in the direction of racial equality owe part of that prosperity to the fact that talented minorities seeking opportunities are disproportionately attracted to such regions? Conversely, are America’s stagnant regions uninterested in a level playing field thereby reinforcing their own relative decline? Our preliminary conclusion, based on the content of this study, is that all of the above trends are presently operative. These issues suggest a broad research agenda, one that needs to be probed deeply in coming decades.

Notes

There is no precise definition of vibrant cities. We examined varying cities identified as economically vibrant, including Dallas, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Nashville. Altering the city mix did not alter our finding that cities fitting the vibrant profile are disproportionately cities where minority residents are the majority.

Regression models utilize control variables (coefficients not reported) measuring firm industry, owner age, gender of owners, firm location in a metro area, and the state in which each firm is located.

References

Aghion, P., & Bolton, P. (1997). A theory of trickle-down growth & development. Review of Economic Studies, 64, 151–172.

Armington, C., & Acs, Z. (2002). The determinants of regional variation in new-firm formation. Regional Studies, 36, 33–45.

Audretsch, D., Dohse, D., & Niebuhr, A. (2010). Cultural diversity & entrepreneurship: A regional analysis for Germany. Annals of Regional Science, 45, 55–85.

Avery, R., R. Bostic, & G. Canner. (2000). CRA special lending programs. Federal Reserve Bulletin (November), 711–731.

Ayres, I., & Siegelman, P. (1995). Race & gender discrimination in bargaining for a new car. American Economic Review, 85, 304–321.

Barr, M. (2005). Credit where it counts: The Community Reinvestment Act & its critics. NYU Law Review, 80, 513–648.

Bates, T. (1973). Black capitalism: A quantitative analysis. Praeger.

Bates, T. (1991). Commercial bank financing of White & Black-owned small business startups. Quarterly Review of Economics & Business, 31, 64–80.

Bates, T. (1993). Banking on Black enterprise: The potential of emerging firms for revitalizing urban economies. Joint Center for Political & Economic Studies.

Bates, T. (1994). Utilization of minority employees in small business: A comparison of non-minority & Black-owned urban enterprises. Review of Black Political Economy, 23, 113–121.

Bates, T. (1997). Race, self-employment & upward mobility. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bates, T. (2006). The urban development potential of Black-owned businesses. Journal of the American Planning Association, 72, 227–238.

Bates, T. (2022). Minority entrepreneurship two. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 18, 330–489.

Bates, T., & Robb, A. (2015). Has the Community Reinvestment Act increased loan availability among small businesses operating in minority neighborhoods? Urban Studies, 52, 1702–1721.

Bates, T., & Robb, A. (2016). Impacts of owner race & geographic context on access to small business financing. Economic Development Quarterly, 30, 159–170.

Bates, T., Bradford, W., & Seamans, R. (2018). Minority entrepreneurship in 21st century America. Small Business Economics, 50, 445–461.

Bates, T., Farhat, J., & Casey, C. (2022). The economic development potential of minority-owned businesses. Economic Development Quarterly, 36, 43–56.

Becker, G. (1993). Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at human behavior. Journal of Political Economy, 101, 385–389.

Bernanke, B. (2007). The Community Reinvestment Act: Its evolution & new challenges. Speech at the March 30, 2007 Board of Governors Community Affairs Research Conference (downloaded from https://www.federalreserve.gov/newevents/speech/Bernanke20070330a.htm). Accessed Apr 2019.

Berry, M., & J. Romero. (2017). Community Reinvestment Act of 1977. Federal Reserve History. Richmond, VA: Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

Berube, A. (2020). Metro Monitor 2020: Prosperity increasing in America’s largest metro areas, but not for everyone. The Brookings Institute.

Blanchard, L., Zhao, B., & Yinger, J. (2008). Do lenders discriminate against minority & women entrepreneurs? Journal of Urban Economics, 63, 467–497.

Bone, S., Christensen, G., & Williams, J. (2014). Rejected, shackled, & alone: The impact of systematic restricted consumer choice among minority customers’ construction of self. Journal of Consumer Research, 41, 451–474.

Bostic, R., & Lee, H. (2017). Small business lending under the Community Reinvestment Act. Cityscape, 19, 63–84.

Bostic, R., & Robinson, B. (2005). What makes Community Reinvestment Act agreements work? Housing Policy Debate, 16, 513–545.

Boston, T. (1999). Affirmative Action & Black Entrepreneurship. Routledge.

Brown, J., Earle, J., Kim, M., Lee, K., & Wold, J. (2022). Black-owned firms, financial constraints, & the firm size gap. American Economic Association Papers & Proceedings., 112, 282–286.

Carter, D., & Wilson, R. (1992). Minorities in Higher Education. American Council on Higher Education.

Casey, C., Glasberg, D., & Beeman, A. (2011). Racial disparities in access to mortgage credit: Does governance matter? Social Science Quarterly, 92, 783–806.

Cavalluzzo, K., & Wolken, J. (2005). Small business downturns, personal wealth, & discrimination. The Journal of Business, 78, 2153–2178.

Chatterji, A., & Seamans. (2012). Entrepreneurial finance, credit cards, & race. Journal of Financial Economics, 106, 182–195.

Cooper, A., Gimeno-Gascon, F., & Woo, C. (1994). Initial human capital & financial capital as predictors of new venture performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 9, 371–395.

Fairlie, R., & Robb, A. (2008). Race & entrepreneurial success: Black, Asian, & White-owned businesses in the United States. MIT Press.

Fairlie, R., Robb, A., & Robinson, D. (2022). Black & White: Access to capital among minority-owned startups. Management Science., 68, 2377–2400.

Fairlie, R. & A. Robb. (2010). Capital access among minority-owned businesses. U.S. Department of Commerce Minority Business Development Agency.

Faulkner, W. (1975). Requiem for a Nun. Vintage Books.

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. (2017). 2016 Small Business Credit Survey: Report on Minority-Owned Firms. Downloaded from https://www.cleveland.org/~/media/content/communitydevelopment/smallbusiness/2016sbcs/sbcsminorityownedreport.pdf.

Handy, J., & Swinton, D. (1984). The determinants of the rate of growth of Black-owned businesses: A preliminary analysis. The Review of Black Political Economy, 12, 85–110.

Immergluck, D. (2004). Credit to the community: Community reinvestment & fair lending policy in the United States. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Jackson, W., Marino, L., Naidoo, J., & Tucker, R. (2018). Size matters: The impact of loan size on measures of disparate treatment toward minority entrepreneurs in the small-firm credit market. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 8, 1–16.

Kim, M. J., Lee, K. M., & Earle, J. (2021). Does the Community Reinvestment Act increase lending to small businesses in lower income neighborhoods? Economics Letters, 201, 110–146.

Kollinger, P., & Minniti, M. (2006). Not for lack of trying: American entrepreneurship in black & white. Small Business Economics, 27, 59–79.

Malizia, E., & Chen, Y. (2019). The economic growth & development outcomes related to vibrancy: An empirical analysis of major employment centers in large U.S. cities. Economic Development Quarterly, 33, 255–266.

Mitchell, K., & Pearce, D. (2011). Lending technologies, lending specialization, & minority access to small-business loans. Small Business Economics, 37, 277–304.

Muro, M. & J. Whiton. (2018). Geographic gaps are widening while U.S. economic growth increases. Brookings Institution

Porter, M. (2016). Inner-city economic development: Learning from 20 years of research & practice. Economic Development Quarterly, 30, 106–116.

Qian, H. (2018). Knowledge-based regional economic development: A synthetic review of knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurship, & entrepreneurial ecosystems. Economic Development Quarterly, 32, 163–176.

Qian, H., & Acs, Z. (2013). The absorptive capacity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 40, 185–197.

Reynolds, P., Carter, N., Gartner, W., & Greene, P. (2004). The prevalence of nascent entrepreneurs in the United States: Evidence from the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics. Small Business Economics., 23, 263–284.

Salop, S., & Stiglitz, J. (1977). Bargains & ripoffs: A model of monopolistically competitive price dispersion. Review of Economic Studies, 62, 493–510.

Schill, M., & Wachter, S. (1995). The spatial bias of federal housing law & policy: Concentrated poverty in urban America. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 143, 1285–1342.

Simms, M. & W. Allen. (1997). Is the inner city competitive? in T. Boston & C. Ross, eds., The Inner City. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers.

Tavassoli, S., Obchonka, M., & Audretsch, D. (2021). Entrepreneurship in cities. Research Policy, 50, 1–21.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Educational Statistics. (2019). Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data System, Fall 2017 & Fall 2018, Completions Component. Downloaded from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d19_322.30

U.S. Department of Justice. (2012). Justice Department reaches settlement with Wells Fargo. Justice News, pp. 1–3.

U.S. Bureau of the Census American Factfinder. (2019). Annual survey of entrepreneurs, survey of business owners, American community survey, & annual business survey.

Yinger, J. (1998). Evidence on discrimination in consumer markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12, 23–40.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this manuscript was not supported by grants, research contracts, or any other external funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Casey, C., Bates, T. & Farhat, J. Linkages between regional characteristics and small businesses viability. Small Bus Econ 61, 617–629 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00703-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00703-9

Keywords

- Minority entrepreneurship

- Community Reinvestment Act

- Accessing bank financing

- Job creation in minority neighborhoods