Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to economic and health crises (“twin crises”) worldwide. Using a sample of firms from 73 countries over the period January to December 2020, we examine stock price reactions of multinational corporations (MNCs) and purely domestic companies (DCs) to the crisis. We find that, on average, MNCs suffer a significantly larger decline in firm value relative to DCs during the stock market crisis caused by the pandemic with notable heterogeneity in this underperformance across both industry and region. The evidence of MNC underperformance is robust to using abnormal returns, an alternative crisis window, a matched sample that accounts for differences in characteristics between MNCs and DCs, alternative model specifications, and alternative proxies for multinationality. Further analysis on the effect of government responses on the valuation gap suggests that stringent government responses exacerbate MNCs’ underperformance. Finally, we show that a stronger financial system mitigates negative crisis returns, especially under stringent government responses, while real factors, such as the firm’s supply chain, investments in human capital, research and development, exacerbate negative crisis returns. Our findings have important implications for managers of MNCs and government policymakers alike and contribute to studies on the international diversification–performance relation by demonstrating a dark side of globalization during a tail-risk event.

Résumé

La pandémie de COVID-19 a entraîné la double crise économique et sanitaire (Twin crises) dans le monde entier. À l'aide d'un échantillon d'entreprises de 73 pays sur la période de janvier à décembre 2020, nous examinons les réactions des cours boursiers des entreprises multinationales (Multinational Corporations - MNCs) et domestiques (Domestic Companies - DCs) à la crise. Nous constatons qu'en moyenne, les MNCs subissent une baisse de la valeur de l’entreprise beaucoup plus importante que les DCs pendant la crise boursière provoquée par la pandémie, et que cette sous-performance des MNCs se caractérise par une hétérogénéité notable à travers les secteurs et les régions. Cette sous-performance des MNCs est également confirmée par nos tests de robustesse utilisant les rendements anormaux, une fenêtre de crise alternative, un échantillon apparié tenant compte des différences en matière de caractéristiques entre les MNCs et les DCs, des spécifications de modèle alternatives, ainsi que diverses mesures de l’internationalisation. Une analyse plus poussée de l'impact des mesures gouvernementales sur l'écart de valorisation suggère que les mesures gouvernementales strictes aggravent la sous-performance des MNCs. Enfin, nous démontrons qu'un système financier plus solide atténue les retours négatifs de la crise, en particulier en cas de réponses gouvernementales strictes, tandis que les facteurs réels, tels que la chaîne d'approvisionnement de l'entreprise, les investissements dans le capital humain, la recherche et le développement, les intensifient. Nos résultats apportent des implications importantes aux managers des MNCs et aux responsables politiques gouvernementaux, et contribuent aux recherches portées sur la relation diversification internationale-performance en démontrant le côté sombre de la globalisation durant un événement à risque extrême.

Resumen

La pandemia del COVID-19 ha llevado a crisis económicas y sanitarias (“crisis gemelas”) en todo el mundo. Utilizando una muestra de empresas de 73 países durante el período comprendido entre enero y diciembre de 2020, examinamos las reacciones del precio de las acciones de las empresas multinacionales (EMN) y de las empresas puramente nacionales (ED) ante la crisis. Encontramos que, en promedio, las empresas multinacionales sufren un descenso del valor de la empresa significativamente mayor que las empresas puramente nacionales durante la crisis bursátil causada por la pandemia, con una notable heterogeneidad en este bajo desempeño tanto por industria como por región. La evidencia del bajo desempeño de las empresas multinacionales es robusta cuando se utilizan rendimientos anormales, una ventana de crisis alternativa, una muestra emparejada que da cuenta de las diferencias en las características entre las empresas multinacionales y las empresas puramente nacionales, especificaciones de modelos alternativos y proxies para multinacionalidad. Análisis adicionales sobre el efecto de las respuestas gubernamentales en la brecha de valoración sugieren que las respuestas gubernamentales estrictas exacerban el bajo rendimiento de las empresas multinacionales. Por último, mostramos que un sistema financiero más fuerte mitiga los rendimientos negativos de la crisis, especialmente bajo respuestas gubernamentales estrictas, mientras que los factores reales, como la cadena de suministro de la empresa, las inversiones en capital humano, la investigación y el desarrollo, exacerban los rendimientos negativos de la crisis. Nuestros hallazgos tienen importantes implicaciones tanto para los directivos de las empresas multinacionales como para los formuladores de las políticas gubernamentales y contribuyen a los estudios sobre la relación entre diversificación internacional y rendimiento al demostrar un lado oscuro de la globalización durante un evento de riesgo de cola.

Resumo

A pandemia do COVID-19 gerou crises econômicas e de saúde (“crises gêmeas”) em todo o mundo. Usando uma amostra de empresas de 73 países no período de janeiro a dezembro de 2020, examinamos reações dos preços de ações de corporações multinacionais (MNCs) e empresas puramente domésticas (DCs) à crise. Descobrimos que, em média, MNCs sofrem um declínio significativamente maior no valor da empresa em relação a DCs durante a crise do mercado de ações causada pela pandemia, com notável heterogeneidade nesse desempenho inferior tanto no setor quanto na região. A evidência do baixo desempenho de MNCs é robusta ao uso de retornos anormais, uma janela de crise alternativa, uma amostra pareada que leva em consideração diferenças nas características entre MNCs e DCs, especificações alternativas de modelos e proxies para multinacionalidade. Análises adicionais sobre o efeito das respostas do governo na diferença de valoração sugerem que respostas rigorosas do governo agravam o desempenho inferior de MNCs. Finalmente, mostramos que um sistema financeiro mais forte reduz retornos negativos de crise, especialmente sob respostas governamentais rigorosas, enquanto fatores reais, como a cadeia de suprimentos da empresa, investimentos em capital humano, pesquisa e desenvolvimento, agravam retornos negativos de crise. Nossas descobertas têm implicações importantes tanto para gerentes de MNCs quanto formuladores de políticas governamentais e contribuem para estudos sobre a relação entre diversificação internacional -desempenho, demonstrando um lado sombrio da globalização durante um evento de pequena probabilidade de risco.

摘要

COVID-19大流行导致了全球的经济和健康危机(“双危机”)。我们以 2020 年 1 月至 12 月期间来自 73 个国家的公司为样本, 研究了跨国公司 (MNC) 和纯国内公司 (DC) 对危机的股价反应。我们发现, 平均而言, 在大流行引发的股市危机期间, MNC的公司价值相对于 DC 的下降幅度要大得多, 并且在整个行业和地区的这种表现不佳的情况存在显著的异质性。 MNC业绩不佳的证据对于使用非正常收益、替代危机窗口、解读MNC和 DC 之间特征差异的匹配样本、替代模型规范和跨国代理来说是稳健的。对政府回应对估值差距影响的进一步分析表明, 严厉的政府回应加剧了MNC的不良业绩。最后, 我们表明, 尤其是在政府采取严厉措施的情况下, 更强大的金融体系会减轻负面危机回报, 而诸如公司供应链、人力资本投资、研发等实际因素则会加剧负面危机回报。我们的研究结果对MNC的管理者和政府政策制定者等具有重要的启示, 并通过在尾部风险事件中展示全球化的阴暗面, 为国际多元化–绩效关系的研究做出了贡献。

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The COVID-19 (or coronavirus) pandemic, which began in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019, has impacted virtually every company on the planet. The effect has differed markedly, however, across firms. Firms with operations in multiple countries and those with international supply chains have been especially vulnerable (Ding, Levine, Lin, & Xie, 2021; Verbeke, 2020) to the devastating effects of the pandemic. This seeming internationalization “discount” is in stark contrast to what extant literature has taught us about the benefits of internationalization during times of crisis, which is that multinational corporations (henceforth MNCs) should weather the storm better than domestic-only firms (henceforth, DCs), not worse.1 This paper provides an empirical investigation into the dark side of globalization based on theories of firms that operate across national boundaries, with a focus on multinational corporate diversification. In particular, we identify country factors that can drive internationalization of the firm to be, on balance, a liability. Understanding the many reasons behind the differential impacts of COVID-19 on MNCs is instructive, as managers think about the global footprint of their firms in new ways.

Among the various cross-country differences that affect how the coronavirus impacts firms are industry characteristics, the levels of economic and financial country development, and government responses to the pandemic.

First, the global pandemic has affected firms differentially based on their industry. The coronavirus has negatively impacted a broad swath of international economic and trade activities: from services, generally, to specific industries, such as tourism and hospitality, medical supplies, and other sectors with global value chains, such as consumer electronics, financial markets, energy, transportation, food, and a range of social activities, all of which were severely damaged (Jackson, 2020). Conversely, the pandemic’s onset affected other industries less negatively and, in some cases, even positively. Examples include technology, healthcare, and firms that benefit when people stay home, such as food delivery services, online entertainment, and online retail, all of which performed well financially during the crisis and recovery periods. The breadth of the global impact, however, has been enormous, especially during the first wave (through April 2020 for most countries), which brought lockdowns almost everywhere. Countries that opted to lockdown were numerous and included even the informal economies in low-income countries that are dependent on supply chains involving, in particular, China.2

Second, the level of development of nations provides valuable information on both government policy efficacy and how severely the twin crises, economic and healthcare, have ravaged national well-being. Concerns about developing countries are growing, given their limited fiscal capacities and less developed financial markets, healthcare systems, and digital infrastructures. The fiscal slack for these countries shrank significantly due to large revenue shortfalls from the pandemic shocks to their economies and to huge expenditures in response to the health and economic crises. Many countries, particularly in Africa, face a looming debt crisis resulting from a large decline in their debt servicing capacity. The importance of debt sustainability is highlighted by the fact that it was at the center of the G20 Summit agenda (Rome, October 2021), and various global measures were discussed, including delay in repayments and attempts to come up with a common platform for the resolution of debt distress.3

Finally, the stringency and efficiency of a country’s response to the virus affects how severely its economy is impacted (Gormsen & Koijen, 2020). Nations such as China that shut down firm operations and imposed strict quarantines on citizens in hopes of keeping the virus at bay, saw their economies contract sharply, but subsequently rebound almost fully. Indeed, by year-end 2020, China’s economy had rebounded to a level 2.3% larger than year-end 2019 (Yao & Crossley, 2021). Many other countries, most dramatically Sweden, took a very different and less severe approach, only to see the virus surge and ultimately cause prolonged economic damage. The post-pandemic economic evolution is also impacting firms differentially, based at least partly on government policy responses. Countries that developed and/or adopted vaccines approved at the end of 2020, such as Israel, Britain, and the U.S., moved into faster recovery than other developed countries, such as European Union members, Canada, and Japan, as well as almost all developing countries.

Against this backdrop, our paper analyzes how the pandemic has impacted the stock returns of firms in 73 countries. We focus on the differences between MNCs and purely DCs. In addition, we assess the role of government responses in influencing the differential impact of the crisis on MNCs and DCs, and explore how country-level real and financial factors influence the performance effects of the crisis. In doing so, our study offers an opportunity to revisit a central research question in the international business and finance literature, namely, the relation between the degree of multinationality and firm value. As we outline in our theoretical framework, the literature provides arguments consistent with multinationality having both costs (agency and information problems, coordination costs) and benefits (diversification, flexibility). This trade-off between costs and benefits suggests that internationalization can have net positive or net negative effects on firm value, depending on economic circumstances. In particular, the trade-off can be altered due to major shocks to MNCs and DCs. We reexamine this premise in a cross-country setting using the exogenous shock of the coronavirus pandemic, which had a pervasive impact on firms with international exposure (Verbeke, 2020). We argue that COVID-19 may have shifted the balance of multinationality’s costs versus benefits toward the dark side during the crisis.

We use global daily stock market data to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on the performance of MNCs and DCs. Although the devastating effects will continue to impact growth and employment levels for many years (Barrero, Bloom, & Davis, 2020), we focus on stock returns here, because stock markets are forward looking and forecast both near-term and long-term corporate earnings (Landier & Thesmar, 2020). As such, stock returns are the market’s best estimates of what the “permanent” impact of the pandemic will be on corporate health.4 For this reason, we examine the differential effect of the pandemic on MNCs and DCs by looking at the initial and intermediate-term pandemic shocks to the stock markets.

An international setting is especially valuable for analyzing the impact of COVID-19 on firms and financial markets because of the staggered introduction of the virus across countries (Ding, Fan, & Lin, 2022), and the differing responses by affected governments around the globe (Megginson & Fotak, 2021). We start by examining the stock price performance of firms before, during, and after the initial pandemic-induced stock market drop in each country. Reflecting the staggered arrival of the virus across countries, we observe heterogeneity in the start and end dates of the pandemic-induced stock market crashes. This suggests that using a one-size-fits-all “crisis period” to study stock market reactions to the pandemic is inappropriate. Indeed, this staggered crisis window allows for an internationalization benefit, consistent with our traditional view, which is that MNCs could theoretically shift their operations to avoid areas hit hardest by the pandemic in a given period of time. Highlighting the importance of this approach, we find heterogeneity in both the duration and the extent of the stock market declines. As a robustness check, we use a common crisis period for all sample countries and find very similar results.

To compare the stock market reactions of MNCs and DCs, we use a sample of firms from 73 countries over the period January to December 2020. In multivariate regressions that control for country fixed effects and several pre-2020 firm-specific characteristics (size, profitability, leverage, asset tangibility, asset risk, stock liquidity, and pre-crisis returns), we find significantly worse stock return (raw and abnormal) performance of MNCs during the initial crash period. Importantly for our purposes, we do not find robust evidence that MNCs exhibited significantly different performance levels than DCs in the months leading up to the crisis, suggesting that this underperformance is not due to a trend going into the pandemic. Moreover, the relative underperformance of MNCs is economically meaningful: MNCs exhibit about 1.7% lower returns (both raw and abnormal) during the crisis period.

In the post-crisis period, we find that, on average, MNCs perform better than DCs, but this finding is sensitive to model specification. Further analysis of cumulative stock market returns over the full sample period appear to suggest that MNCs do not fully recover from their crisis-period underperformance by the end of our sample term (December 2020). Our core findings are robust to using alternative proxies for internationalization, to using daily returns, to including various fixed effects, and to using a matching technique to account for differences in characteristics between MNCs and DCs. Overall, these results suggest that internationalization can have a dark side during a tail-risk event, such as a pandemic.

We next examine whether the differential crisis-period effects of COVID-19 on MNC and DC stock returns vary across industries and geography. Although the magnitude of the performance gap varies along both of these dimensions, MNC performance tends to be more adversely affected by the pandemic than that of DCs. At the industry level, MNCs significantly underperform in Durables, Manufacturing, Other, and Oil & Gas. Conversely, MNCs significantly outperform their domestic counterparts in Healthcare/Drugs. Analyses on specific industries provide evidence that the Hospitality industry was hit particularly hard and that the benefits seen in the Healthcare/Drugs industry stem from pharmaceutical firms, i.e., drug makers. With regard to differences across regions, MNCs underperform during the crisis period in East Asia & the Pacific, Europe & Central Asia, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Conversely, MNCs outperform DCs in North America. At the country level, MNCs underperform relative to DCs during the crisis period in all of the countries we examine (i.e., China, the U.K., Sweden, Italy, and Singapore) except for the U.S., where they outperform their domestic-only peers.

To further our understanding of the heterogeneous stock price reactions of MNCs across regions and countries, we explore whether the performance gap is driven by important cross-country differences in the strength of a country’s response to the pandemic. We find that the crisis-period valuation gap between MNCs and DCs is generally increasing in the strength of government responses to the pandemic. Responses associated with the greatest MNC underperformance are school closings, workplace closings, restrictions on gatherings, restrictions on international travel, public information campaigns, and contact tracing. We also find that the strength of government responses affects the performance of MNCs and DCs during the post-crisis recovery period. More specifically, we find that responses, such as international travel controls, contribute to the performance gap during the post-crisis recovery period, while others, such as income-support programs, reduce the MNC performance gap.

We next build on Gande, Schenzler, and Senbet (2009) to examine how real and financial factors moderate the performance effects of the crisis, and how their effects are shaped by the stringency of government responses. Our findings are in direct contrast to the impacts of traditional crises, which typically stem from the weakness of financial systems, and for which the real effects of a globally diverse footprint provide a benefit. Indeed, our findings suggest the opposite in the course of this pandemic-borne crisis. Real factors, such as exported goods or supply chain materials, and investments in human capital, R&D, and physical capital exacerbate the crisis-period performance gap between MNCs and DCs. The strength of various financial proxies, such as capital market depth, foreign ownership, the lack of state ownership disruptions, and diversity of credit sources, which can provide capital and ensure liquidity when governments necessarily shut down operations, are positive drivers of MNC performance through the COVID-19 crisis.

Finally, we examine whether the impacts found for the real and financial effects differ for firms in countries with bifurcated data based on median government response to the pandemic. While some real factors are less important than others, the impacts of most real factors in the high stringency subsample are consistent with the impacts found in the full sample. Importantly, the results also show that the positive impact of the financial factors found in the whole sample analysis is driven by the subsample with a strict government response, where real factors became liabilities for MNCs. This suggests that capital comes to the rescue when real aspects of a firm become a liability. This is somewhat intuitive based on what we know about how businesses struggled during government-imposed lockdowns. This result makes clear the importance of the financial dimension to MNCs when navigating multiple country responses to the pandemic and is in stark contrast to the role the financial world plays in many historical crises.

Our paper contributes to a new and growing literature on the coronavirus and its impact on firms using stock market data (Ashraf, 2020; Bae, El Ghoul, Gong, & Guedhami, 2021; Baker, Bloom, Davis, & Terry, 2020; Ding et al., 2021; Duan, El Ghoul, Guedhami, Li, & Li, 2021; Fahlenbrach, Rageth, & Stulz, 2021; Harjoto, Rossi, Lee, & Sergi, 2021; Narayan, Phan, & Liu, 2021; Ramelli & Wagner, 2020; Shen, Fu, Pan, Yu, & Chen, 2020). We extend these studies by providing evidence on the differential effects of the pandemic on the stock returns of MNCs and DCs. In this regard, our paper is specifically related to Ramelli and Wagner (2020). Using a sample of North American firms, Ramelli and Wagner (2020) find that firms, whose supply chains are in affected areas (e.g., China), are more likely to be negatively affected, especially during the early pandemic period. We differ from these studies by taking a global approach and analyzing a large sample of 73 countries, with varying economic, institutional, and political environments as well as government responses to the pandemic. Importantly, while Ramelli and Wagner (2020) capture a narrow globalization dimension using exposure to just China, we perform a cross-country analysis based on a broader sample of 73 countries and employ different proxies for multinationality grounded in prior research.

Our paper also contributes to the robust literature on the costs and benefits of internationalization. Prior studies document positive valuation effects of internationalization (Errunza & Senbet, 1981, 1984; Gande et al., 2009; Li, Qiu, & Wan, 2011; Mansi & Reeb, 2002; Mihov & Naranjo, 2019). Focusing on the 2008–2009 financial crisis, Chang, Kogut, and Yang (2016) and Mihov and Naranjo (2019) find that the benefits of internationalization increased during the 2008 financial crisis. In contrast, we find evidence of a global diversification discount in valuation during the COVID-19 crisis. This surprising result suggests that globalization can have a dark side during tail-risk events. Grounded in the work of Gande et al. (2009), our additional analyses on the roles of country-level real and financial factors as well as their interactions with the stringency of government responses provide new insights into the determinants of the global diversification discount that we document.

A NOVEL TWIN CRISIS

Background

COVID-19, a virus new to human beings, emerged in Wuhan, China, in December of 2019 and quickly spread to the point where China was forced to shut down its economy to contain the spread. Despite these efforts, the virus rapidly spread to Thailand, South Korea, and Japan. The World Health Organization (WHO) deemed it a world health emergency only 1 month after its first known infection in January 2020. In the next 2 months, the virus would continue its rapid spread to impact more than 190 countries, resulting in the WHO declaring it a pandemic on March 11. To date, it is difficult to overstate the magnitude and severity of the pandemic’s impact. It has been both a health and economic crisis of epic proportions.

The general response of governments facing this pandemic has been to limit unnecessary travel, shut down educational institutions, restrict access to workplaces and, in many cases, compel citizens to shelter in place, causing dramatic contractions to their economies. Making matters worse, businesses and governments were generally unprepared. The tools that governments traditionally use to “fix” economic crises offered only limited remedies because this crisis was not born from financial or monetary system weaknesses, as is typical, but rather from a health crisis. This limited the guidance found in most academic literature surrounding “twin crises” because the vast majority of extant studies examine how macroeconomic factors affect a different set of twin troubles: banking and currency crises (Glick & Hutchison, 2001; Kaminsky & Reinhart, 1999).

While there is research on the health effects (in most cases, mental health) of economic crises (Karanikolos, Mladovsky, Cylus, Thomson, Basu, Stuckler, Mackenbach, & McKee, 2013), it is mostly lacking in the case of simultaneous economic and health crises. This lack of research attention is understandable, because we have not seen a pandemic this serious since the Spanish Flu pandemic during and after World War I.5 Considering both the severity of these twin crises and the dearth of research on pandemic-induced economic crashes, the need for research on various aspects of how these conjoined crises impact firms, investors, global markets, and the world economy is imperative as both government and business leaders struggle to stave off crises of Depression-era proportions.

Related Research on the Effects of the Pandemic

A growing body of research focuses on evaluating and understanding the effects of the pandemic on stock market performance. Reflecting the unprecedented nature of this event, Baker et al. (2020) find that COVID-19 had a far greater impact on the U.S. stock market than any other pandemic or disease-related event in the past 120 years. From 1900 until 2019, there were 1100 daily stock price movements (up or down) that exceeded 2.5%; from February 24 to April 20, 2020 alone, there were two dozen. Using high-frequency data for 53 emerging and 23 developed countries from January 14 to August 20, 2020, Harjoto et al. (2021) document significant negative stock market reaction to COVID-19 cases and deaths. However, such effects differ across emerging and developed countries, as well as during rising infection and stabilizing spread periods.

Related studies find that the COVID-19 crisis has sharply differing impacts on corporations based on the degree of their pre-pandemic financial flexibility, leverage, cash holdings, and institutional ownership. Using a sample of U.S. firms, Ramelli and Wagner (2020) examine the cross section of stock price reactions to COVID-19. They find that exposure to China resulted in lower stock returns during the early pandemic period (January 2 to February 21), but the effect is insignificant, or even positive, during the crisis (February 24 to March 20). The authors also find that firms with high leverage and low cash holdings perform poorly during the crisis period. Fahlenbrach et al. (2021) show that firms with high financial flexibility (Hadlock & Pierce, 2010; Kaplan & Zingales, 1997; Whited & Wu, 2006) and liquidity (Huang & Ritter, 2022) suffer significantly lower stock price declines than more financially constrained firms.

Glossner, Matos, Ramelli, and Wagner (2021) find that U.S. stocks with higher institutional ownership, especially active and short-term owners, are more likely to collapse during the stock market crash period. They also find that this underperformance is driven by a “flight to quality” by active institutional investors who rebalance their equity portfolios towards more financially resilient firms. Acharya and Steffen (2020) document a “dash for cash,” where all firms draw down bank credit lines and build up cash reserves for fear of becoming a “fallen angel” by being cut off from external financing by creditors and investors. Halling, Yu, and Zechner (2020) show that bond issuance increases sharply both from firms with debt rated A or higher and those rated BBB or lower. The issuance volume accelerates following the federal government’s fiscal and monetary policy interventions of March–May 2020.

Using a cross-country setting, Ding et al. (2021) examine the role of pre-pandemic corporate characteristics in explaining cross-firm stock price reactions to COVID-19. They find that the pandemic-induced drop in stock returns is less pronounced among firms with stronger pre-2020 finances, less exposure to COVID-19 through international supply chains and customer locations, stronger CSR engagement, and less opportunistic management. Using the context of China and a real option framework, Shen et al. (2020) find that the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on firm performance is more pronounced among firms with smaller investment scale and sales revenue. Relatedly, Gu, Ying, Zhang, and Tao (2020) find that private and smaller firms exhibit larger losses compared to state-owned and larger firms, respectively.

Focusing on the worldwide banking sector, Demirgüç-Kunt, Pedraza, and Ruiz Ortega (2021) find that bank stocks underperform their domestic markets and other non-bank financial firms during the crisis period. This is consistent with banks playing a countercyclical lending role to support the real sector. The authors also show that response measures implemented by government authorities, such as liquidity support, borrower assistance, and monetary easing, generally moderate the adverse stock market consequences of the crisis. Acharya, Engle, and Steffen (2021) shed additional light on the causes of the crash of bank stock returns during the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. They show that the rush to draw down committed lines of credit is a key reason that bank stocks seriously underperformed throughout 2020, and continued to lag the overall market in early 2021. Duan et al. (2021) study the effect of the pandemic on bank systemic risk in an international setting. They show that the pandemic increases systemic risk across countries, with the effect being moderated by formal bank regulation and safety net (e.g., deposit insurance), ownership structure (e.g., foreign and government ownership), and informal institutions (e.g., culture and trust).

While the studies above contribute new insights into the impact of the pandemic on stock prices, little has been documented about how stock markets priced multinationality during the pandemic crisis, or the differential stock price impact of the pandemic on MNCs relative to their domestic counterparts. In particular, what does the pandemic teach us about the costs and benefits of globalization suggested in existing finance and international business theories? Is there a dark side awakened by COVID-19? What country-level factors amplify or mitigate this effect? We attempt to answer these questions in this paper. Specifically, we evaluate the stock price reactions of firms to the pandemic crisis based on their degree of international involvement. We investigate potential heterogeneous effects across industries and geography. We also examine whether and how government responses to the pandemic and country-level real and financial factors influence the value of multinationality.

THEORETICAL BASES FOR THE VALUE OF MULTINATIONALITY: FINANCE AND INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS PERSPECTIVE

The impact of multinationality on firm value is a longstanding question in the international business and finance literature. Early research on the value of an MNC relative to a DC suggests that the value of a multinational should exceed that of an otherwise comparable domestic company (Agmon & Lessard, 1977; Errunza & Senbet, 1981, 1984; Rugman, 1979; Senbet, 1979). Gande et al. (2009) explain that the internationalization of a firm, as in the case of MNCs, adds value based on both financial and real aspects of the cross-country scope of the firm. The financial aspect is represented in the imperfect global capital markets theory (Errunza & Senbet, 1981, 1984), where MNCs “complete the markets” by providing investor access to countries with investor restrictions. The real aspect is represented in the internalization theory (Caves, 1971; Coase, 1937; Dunning, 1973), where MNCs are able to internalize some markets for their intangible assets (e.g., production technology, employees’ skills, managerial know-how, intellectual property, brand value) to increase their market values.6

The existence of imperfections in the product and factor markets per se is not sufficient to rationalize internationalization (e.g., through direct foreign investment), but these imperfections may accord systematic and special advantages to MNCs over purely DCs. If such advantages exist, they will manifest themselves in the market value of the MNC. As Errunza and Senbet (1981) posit, the current market value of the MNC can be decomposed into value associated with (a) currently held assets and (b) options for future investments, including options for international involvement through discretionary investments. Such investments accord real options to MNCs and are consistent with the internationalization theory associated with intangibles (e.g., R&D, advertising). They may also be valued in a real options valuation framework as formalized by Errunza and Senbet (1981).

Counterbalancing these theories is the managerial objectives theory, which suggests that the conflicts of interest that exist between managers and shareholders become larger as the scope of the firm increases (Berger, El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Roman, 2017). Additionally, early research on the industrial diversification discount theory – as in a conglomerate – suggests that diversification across industries results in value destruction (Berger & Ofek, 1995; Lang & Stulz, 1994). As with the internalization theory, these theories may be considered real rather than financial. However, the former has a positive valuation effect (see Gande et al., 2009).

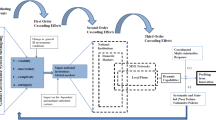

We note that these theories are not mutually exclusive. They signify important trade-offs in globalization that depend on a variety of characteristics that vary across time (Denis, Denis, & Yost, 2002). These theories imply that there are “bright” and “dark” sides of globalization that can be counterbalanced. On the positive side are the indirect investor diversification effects of globalization through MNCs in the face of incomplete/imperfect markets (financial effect), and the effect embedded in international theory (real). On the negative side are broad governance issues from reduced coordination and distorted managerial incentives for undertaking value-destructive international acquisitions (empire building), as well as the increased difficulties of coordinating subsidiaries and vast supply chains.

In this paper, we focus on the value of internationalization during a global crisis period, such as a pandemic. Given the implications of the foregoing theories, the overall impact of the firm’s international scope on its value is based on the aggregate impact of all of the theories, whether they reside in the real or financial influences on a firm. We argue that global shocks, such as COVID-19, may alter the trade-off between the bright and dark sides of globalization, though perhaps only temporarily. As a result, internationalization can have net-negative or net-positive effects on firm value. It is possible that the pandemic erased the international diversification benefits when access to imperfect markets – primarily for real assets – was effectively shut down. This negative shock to the global trade of real assets, which is essentially unprecedented in the post-World War II era, revealed a heretofore undocumented vulnerability of globally diverse firms that financial crises, such as a banking crisis, had never exposed. Such a negative shock to MNCs’ supply chains could transform global diversification benefits into liabilities, effectively changing everything we think we know about decisions involving internationalization of a firm. Put differently, it is possible that the pandemic represents a tail event, where the positive impacts of internationalization are overwhelmed by the negative impacts of the pandemic-born (global) crisis. Consistent with this notion, Ramelli and Wagner (2020) find that exposure to China negatively impacted the stock returns of U.S. firms during the pandemic, which suggests that MNCs’ global expansion can, in certain cases, be a liability. Thus, the dark side of globalization is hypothesized through the MNC differential negative returns as follows:

Hypothesis 1a

Crisis returns for MNCs are significantly more negative than those for DCs.

Alternatively, it is possible that the pandemic amplifies the investor diversification benefits of MNCs due to the staggered waves of the pandemic. In addition, MNCs’ privileged access to low-cost inputs from diverse supply chains and flexible production capacity from subsidiaries in various countries around the world could be more valuable during crisis periods as the peaks and troughs of COVID cases differ across various countries in an MNC’s footprint. Conversely, DCs do not have the same ability to shift inputs or production geographically. This staggered COVID intensity may allow some firms to shift production from hot spots to areas that are seeing relatively few cases, making any negative impacts of the pandemic less severe for MNCs than DCs. An example of this can be seen in AB InBev, one of the largest MNCs in the world. It ramped up production in Europe shortly after many of its countries opened outdoor dining. Through data analysis and forecasting, they sought to make production and sales decisions based on the path of the pandemic progression. The result, according to the company, is that the AB InBev brands are performing better than they did in 2019.7 Thus, the positive side of globalization is hypothesized through the MNC differential positive returns as follows:

Hypothesis 1b:

Crisis returns for MNCs are significantly more positive than those for DCs.

From a financial perspective, international portfolio theory suggests that the benefits of internationalization may disappear, for example, during a health/financial crisis that reaches virtually every country in the world, due to an increase in return correlations across countries during difficult times (e.g., Ang & Bekaert, 2002; Campbell, Koedijk, & Kofman, 2002; Erb, Harvey, & Viskanta, 1994; King & Wadhwani, 1990; Longin & Solnik, 2001). As a result, total firm risk should return to the level of a purely domestic firm that does not diversify away at least some firm-specific risk. This suggests that the pandemic-induced drop in MNC value, controlling for firm size, should be in line with that of its purely domestic counterparts. Stated formally, our basic hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 1c:

Crisis returns for MNCs are insignificantly different than those for DCs.

In addition to the average effect of the crisis on MNC performance, we examine potential heterogeneous effects across industries and geography. Shen et al. (2020) show that the adverse effect of the pandemic on firm performance in China is more pronounced in high-impact industries (e.g., tourism, accommodation, transportation, real estate, construction, and export manufacturing) and highly affected regions (e.g., Hubei, Hunan, Beijing). We argue that the impact of the pandemic on the trade-off between the bright and dark sides of globalization is heterogenous across industries and geography. Industries differ in terms of their reliance on and access to real and financial factors, as well as susceptibility to demand shocks – resulting from higher unemployment and reduced income – and labor supply shocks from social distancing measures (e.g., Brinca, Duarte, & Faria-e-Castro, 2021; del Rio-Chanona, Mealy, Pichler, Lafond, & Farmer, 2020). Consistent with this view, a wealth of evidence suggests that the onset of the COVID-19 crisis has disproportionately affected some industries over others. For example, the travel tourism industry (e.g., air transportation, cruise lines, hotels), entertainment and restaurants, and industries with global value chains are proven to be more vulnerable to the crisis-induced restrictions globally, as evidenced by their deteriorating performance (e.g., Shen et al., 2020) and depletion of cash reserves (e.g., De Vito & Gomez, 2020).8 Other industries (e.g., technology, medical providers, online entertainment, online retail) showed better resilience and performance during the pandemic crisis, benefiting from increased demand for their products and services, reduced exposure to labor supply shocks due to telecommuting capabilities, and less reliance on global supply chains (i.e., global trade of real assets).

In the case of geographic heterogeneity in the disparate impact of COVID on MNCs, country-level differences in their degree of financial development, as well as corporate governance, may be pivotal.9 Gande et al. (2009), for example, document that the valuation effects of multinationality through indirect portfolio diversification decline if the countries into which the MNC diversifies have lower-quality corporate governance. The decline is both for the real and financial effects of multinationality. Alternatively, the variation in financial development may help explain the differential valuation effect of the MNC through better access to these markets for investors rather than using the MNC as a vehicle for portfolio global diversification. Considering the discussion on both industry and geography heterogeneity above, our second prediction is:

Hypothesis 2:

The differential stock price impact of the pandemic on MNCs, relative to DCs, exhibits industrial and regional heterogeneity (i.e., differs across industries and regions).

The pandemic has triggered unprecedented government responses around the world, including measures related to closure, containment, and health (e.g., lockdowns, stay-at-home orders, social distancing, vaccines), as well as economic support policies. Moreover, each response may vary in its strength and permanency (Hale, Angrist, Goldszmidt, Kira, Petherick, Phillips, & Tatlow, 2021). Prior research shows that national differences in economic, financial, political, and cultural institutions affected the significance of the pandemic and disparities of government responses (e.g., Chen, Peng, Rieger, & Wang, 2021; Dheer, Egri, & Treviño, 2021). Some of the containment measures were aimed at addressing the spread of the virus, but they also caused adverse economic effects on households due to loss of income and/or businesses due to reduced demand for their products and services, as well as labor supply shocks. In addition, economic support measures, which include household direct income support, debt relief, and/or fiscal stimulus, vary substantially across countries (Hale et al., 2021), reflecting differential access to resources. Given that these response measures can have implications for the duration of the crisis in some countries more than others, they are likely to disproportionately impact MNCs due to responses by multiple governments and jurisdictions. Collectively, this can be difficult, if not impossible, to navigate successfully. As an illustration, we refer to the new Omicron variant surge at the end of 2021, which resulted in thousands of flights being canceled worldwide. This is mainly due to renewed international travel restrictions as well as staffing shortages (flight crew and operations personnel) caused by stricter testing policies and quarantine requirements. Carsten Spohr, CEO and chairman of Deutsche Lufthansa AG, for example, announced the cancellation of 10% of the group’s total flights over the period mid-January to February 2022.

Prior research on the performance implications of government response policies finds mixed evidence. Ding et al. (2021) document a positive stock market reaction to government containment and closure policies, as well as government stimulus. In contrast, Ashraf (2020) and Aharon and Siev (2021) find that strict government responses, particularly social distancing measures, are associated with negative market returns, which they attribute to anticipated negative effects on the economy. These authors document generally positive market reactions to economic interventions. In the context of the banking sector, Duan et al. (2021) show that strict government response is a channel through which the pandemic increased systemic risk across countries. However, they do not find that economic measures affect systemic risk. Taken collectively, prior research implies that the impact of government interventions on stock returns depends on the type of intervention. Based on this discussion, we posit that the strength of government responses can alter the trade-off between the bright and dark sides of globalization, leading to our third prediction:

Hypothesis 3:

The differential stock price impact of the pandemic on MNCs relative to DCs is influenced by the stringency and type of government responses.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Stock Price Information

Our stock price data come from Compustat Global Daily. We collected firm-level stock prices from January 1 to December 31, 2020, and categorized the dates into pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis periods. In keeping with the stock price crash risk literature, originated by Hutton, Marcus, and Tehranian (2009), we define the start of the crisis period as the first day of five consecutive trading days with crash returns, where crash return refers to a return that is below 3.09 times the standard deviation of the mean daily returns from November 1 to December 31, 2019. We use the equally weighted average daily return of all firms within a country from day t − 7 to day t to compare daily returns in our sample period with crash returns. We define the end of the crisis as the date when the lowest cumulative return since the beginning of the crisis was reached. We calculate the cumulative returns for each period to include in our multivariate analyses. The advantage of this approach is that we can account for the staggered introduction of the virus across countries, and hence heterogeneity in crisis onset and duration, which allows for the positive net effect of internationalization. Nevertheless, for thoroughness, we also re-run our main analysis using a common crisis period for all sample countries.

Firm Internationalization

Following prior research (Gande et al., 2009; He & Ng, 1998; Jorion, 1990; Li et al., 2011), we capture firm internationalization with a dummy variable, “MNC”, that equals “1” if the fraction of firm’s foreign sales divided by its total sales is greater than 10%, and “0” otherwise. We obtain foreign sales data from the Compustat Segments database. As a robustness check, we also define “MNC” using a continuous measure, namely the ratio of foreign sales to total sales.10

Control Variables

To isolate the stock market performance of MNCs around the pandemic period, we include traditional control variables to account for factors that impact firm-level returns. These variables, which are found in all regression models, include firm size (Ln(Assets)), proxied by the natural logarithm of total assets, profitability (ROA), measured as the operating income scaled by total assets, leverage (Leverage), measured as the ratio of long-term debt to total assets, asset tangibility (Asset Tangibility), measured as the ratio of property, plant, and equipment to total assets, asset risk (ROA Volatility), calculated as the standard deviation of ROA over the past 5 years, stock liquidity (Illiquidity), calculated as the absolute value of daily return-to-volume ratio averaged over the fiscal year. In addition, we control for pre-crisis returns in the models examining the crisis and post-crisis returns. “Appendix A” defines all variables used in the analyses.

Our baseline analysis utilizes these data to relate firm performance before, during, and after the crisis to the internationalization of the firms in our sample, controlling for various firm-level characteristics that impact stock market performance. Formally stated, our baseline model is:

where Ri,d represents stock return, MNCi is our proxy for the internationalization of the firm, and Xi includes both firm-level characteristics and country fixed effects. The generalized and robustness analyses build on this basic model by altering our proxies, interactions among the relevant explanatory variables, empirical approach, and examining how MNC underperformance varies with both country-level factors and government responses to the pandemic.

For our baseline analysis, we include country-level fixed effects to control for within-country heterogeneity. Since the sample used for our base analysis contains only three observations – pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis – for each firm, we cannot include firm fixed effects. Even our firm-day analysis does not allow for the inclusion of firm fixed effects because foreign sales, the basis for our internationalization variable, is based on an annual figure that is time-invariant in our sample (i.e., we do not have daily values). Firm fixed effects in this setting would proxy for all firm characteristics, including whether a firm is an MNC. As such, we limit our fixed effects to country and day fixed effects in the firm-day analysis. Moreover, our analyses that examine country-level real and financial factors use regional fixed effects instead of country fixed effects because the added country-level factors are time-invariant in our sample. This means that for our sample term, we have one value for each factor for each country. In this case, using country fixed effects would subsume these factors. Notwithstanding these limitations, we provide robustness analyses that add various fixed-effect combinations to ensure the sustainability of our core results.

Additional Country-Level Data

In an effort to take a deeper dive into factors that either exacerbate or mitigate the disparate impact of COVID-19 on MNCs relative to DCs, we expand our model to include additional country-specific factors that speak to both the existing infrastructure related to real and financial factors and the diverse ways that countries responded to the pandemic.

Our country-level real and financial factors come from various sources, including the World Trade Organization, Doing Business, ILOSTAT, National Sources, the IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook, OECS Education at a Glance, UNESCO, the OECD, and Euromonitor International. Regarding real factors, our data highlight three categories of a nation’s infrastructure surrounding real assets that can affect firm performance: supply chain, human capital, and investment in current (fixed assets) and future (Research & Development) production.

Our country-level stringency data come from the University of Oxford, which has recorded the various governmental responses to COVID-19 around the world as the pandemic has spread globally.11 Researchers there created the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT), which measures government responses in terms of policy and intervention. These quantitative measures allow researchers to analyze the impact of government responses to the pandemic in terms of various outcomes. The data indicators are measured in one of two ways: (1) ordinal, which provides a level of response/policy relative to what is possible, or (2) numeric, which is a specific number, such as dollar value. Information collected by OxCGRT has three main categories: (1) containment and closure, (2) economic response, and (3) health systems.12 Examples of indicators from containment and closure include school closing, workplace closing, cancellation of public events, restrictions on gathering size, closing of public transport, stay-at-home requirements, restrictions on internal movement, and restrictions on international travel. Examples of indicators from the economic response include income support, debt/contract relief for households, fiscal measures, and giving international support. Examples of indicators from health systems include public information campaigns, testing policy, contact tracing, emergency investment in healthcare, and investment in COVID-19 vaccines. The three categories of government responses have both health and economic outcomes, which feed into our analysis of the pandemic impact on MNC performance relative to the domestic counterpart.

Data Characteristics

Our global sample of firms spans 73 countries in seven regions. Specifically, our sample comprises East Asia & the Pacific, Europe & Central Asia, Latin America & the Caribbean, Middle East & North Africa, North America, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan African regions.13 Table 1, Panel A, provides information on the number of MNCs and DCs by country within the seven regions, as well as their aggregated asset values. There exists vast heterogeneity in both the number and size of MNCs as well as DCs in our sample.

Table 1, Panel B, demonstrates the diversity of our sample along multiple fronts. First, we observe diversity in the timing of the crisis, which began in Asia and quickly spread to Europe and North America. Latin America & the Caribbean, and the Middle East & North Africa, saw slightly delayed onsets. Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries saw a further delay, although their economies were impacted immediately as a result of spillover effects from their global economic partners, particularly the EU and China.

Likewise, there is variation in the average daily returns during the crisis period, which begins with the first day of the five consecutive trading days with crash returns. As mentioned earlier, crash returns are characterized as those below 3.09 times the standard deviation of mean daily returns from November 1 to December 31, 2019. Specifically, the returns range from − 2.7% to − 1.2% for MNCs, and from − 2.2% to − 0.4% for DCs. The difference in means for MNCs and DCs is statistically significant at the 1% level for six of the seven regions, with the decline being greater for MNCs in all but one of the regions (i.e., Middle East & North Africa). The most extensive differences are seen in South Asia and SSA. This may be attributable to diversity in firm and industry characteristics across regions. In particular, the dominant industries in SSA are agriculture, mining, tourism and hospitality, and commodities, which were impacted early and hard, even if the virus itself was slow to arrive.

ANALYSIS OF THE IMPACT OF COVID-19

Our multivariate analysis provides results that are consistent with those in our univariate analysis. Specifically, the financial crisis induced by COVID-19 impacts MNCs differently than DCs. Panel A provides results using raw returns and Panel B provides results using abnormal returns. Turning first to Panel A of Table 2, Model 1 controls for firm size, profitability, and leverage, and Model 2 builds on Model 1 by further including asset tangibility, asset risk, and stock liquidity. We find that, prior to the COVID-induced crisis, MNC returns are insignificantly different from those of DCs. When we focus on the crisis period, however, MNC returns become significantly worse than those of DCs. Specifically, MNC returns are 1.8% lower than those of DCs, when controlling for firm size, profitability, and leverage (Model 3), and 1.7% lower when we expand the control variables to include asset tangibility, asset risk, stock liquidity, and pre-crisis returns (Model 4). The post-crisis results show that MNCs outperform DCs, suggesting that the underperformance of MNCs may be temporary. To further explore this possibility, in unreported tests we compare the cumulative stock market returns of MNCs and DCs from the onset of the crisis to December 2020. We do not find consistent evidence that MNCs fully recover.14

Panel B, which replicates Panel A using abnormal returns, obtained by subtracting an individual firm’s return during the event period from the average return from January 1 to December 31, 2019, provides results that are similar. More specifically, using the previous year’s returns as a benchmark, we find that the results are unchanged in terms of statistical significance and are remarkably similar with regard to the economic magnitude. The stability of these findings suggests that our core results do not stem from a risk-based explanation.

The results of Table 2 are notable in that they reveal a downside, or a “dark” side, of the internationalization of a firm’s footprint, which had heretofore been considered – on balance – to be a positive driver of stock return. The international operations of an MNC were thought to insulate the firm from country-specific (or even region-specific) crises. These results suggest that this conclusion is not as robust as we once thought it was. While it is comforting to note the potentially short-lived nature of this significant underperformance, it highlights the idea that tail events can potentially change the balance of the benefits and costs of internationalization, resulting in a global footprint becoming a liability instead of a reward.

We can further unpack the effect of the pandemic by examining firm and industry characteristics and their interactions with globalization. To demonstrate the diversity of COVID-19’s impact on firms grouped by industry, Panel A of Table 3 presents the results of an MNC indicator interacted with industry indicators, as defined by the Fama–French 12-industry classification. The results are based on raw returns in Model 1 and abnormal returns in Model 2.

We first look at Model 1 and focus on the coefficients on the interaction terms. Note that the main effect of MNCs is left out of the model for two reasons: (1) it allows all of the Fama–French industries (which are exhaustive) to remain in the model, and (2) it makes the interpretation of MNC performance in the Fama–French industries more straightforward. Notable results here include that MNCS in Durables, Manufacturing, Other, and Oil & Gas industries significantly underperformed DCs. In contrast, we see that MNCs in the Healthcare and Drugs industries significantly outperformed DCs. The reason for this comparative advantage of MNCs operating in the Healthcare/Drugs industry during the pandemic is straightforward, since these industries are presumed to impact positively the mitigation and treatment of the virus. Model 2, which utilizes abnormal returns, provides results that are similar. The only real difference here is the addition of significant underperformance of MNCs in utilities.

Panel B of Table 3 takes a more nuanced approach. Here, we identify specific industries that are strongly impacted by the pandemic, whether that impact is positive or negative. We again omit the main effect of MNCs. Such industries include air transportation, technology, healthcare, digital technology, hospitality, drugs, communications, and medical supplies. We include healthcare and drugs separately here to take a deeper dive into the results from Panel A that suggest Healthcare/Drugs sees a positive impact. To unpack the average effect, we interact the “MNC” variable with specific industries, and find that the effects vary by industry. In particular, the magnitude and statistical significance of the coefficient of the interaction between “MNC” and industry suggests that the impact is largely dependent on the industry. In particular, MNCs in Hospitality suffer a greater return deficit than DCs (− 5%). By contrast, MNCs in Drugs do better, garnering 4.5% higher returns than DCs. It is notable that MNCs in healthcare actually do worse, albeit insignificantly. This is counterintuitive at first blush until we realize that many aspects of healthcare were halted while hospitals focused on caring for those sick with COVID-19. Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson saw record profits after developing their vaccines. Again, the results in Model 2, which utilizes abnormal returns, are similar.

We now move from industry analysis to consider regional differences. To demonstrate the diversity of COVID-19’s impact on firms by region, Panel A of Table 4 displays the results of interacting an MNC indicator with indicators for region, as defined by the World Bank Group, again omitting the main effect of MNC for the reasons outlined above. The results suggest that the financial impact of COVID-19 is quite heterogeneous regionally. Four of the seven coefficients are significantly negative, suggesting that MNCs significantly underperform relative to their DC peers in these regions. Specifically, MNCs fare worse than DCs in East Asia & the Pacific, Europe & Central Asia, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Conversely, MNCs outperform their DC counterparts in only one region – North America. The magnitude of this divergence in performance is for the most part greater than that found in Table 2, suggesting that the results in Table 2 obscure the heterogeneity in MNC underperformance across regions. The results in Model 2, which are based on abnormal returns, yield similar inferences. The only significant difference is found in Europe & Central Asia, where the coefficient falls just shy of conventional significance levels when using abnormal returns.

Panel B of Table 4 takes a closer look at specific countries: U.S., China, U.K., Sweden, Italy, and Singapore. Interacting dummies for these countries with our MNC indicator (and again omitting the main effect of MNC) provides more evidence of the contrasting effects of COVID-19 on MNCs versus DCs. Supporting the results in Panel A, the interaction term in Model 1, which displays results for raw returns, suggests that U.S.-based MNCs actually do better than DCs during the crisis, whereas MNCs in China, U.K., Sweden, Italy, and Singapore fare significantly worse than DCs. The results obtained using abnormal returns, reported in Model 2, confirm this finding.

This geographic heterogeneity begs further analysis, given the many country-level differences relevant to firm performance during the pandemic. Why do MNCs perform better than DCs in some countries (or regions), but worse in others? To address this question, in the next section we examine the role of the heterogeneous government responses to the pandemic, and further explore how country-level real and financial factors influence the performance effects of the crisis. Given that the results are virtually unchanged when using abnormal returns, we focus on raw returns going forward for brevity.15

COUNTRY-LEVEL FACTORS AND DIFFERENTIAL STOCK PRICE IMPACT

Government Responses to COVID-19

We next evaluate the differential sensitivity of stock price reactions based on the extent to which governments differed in their responses to COVID-19. In Table 5, we exploit the daily variation in government responses and regress daily returns over the crisis period on an MNC indicator, various country-level stringency indices, and interactions of the MNC indicator with these indices. Firm-day observations are used in the regression due to the periodicity of the government response data. All models include controls for firm size, profitability, leverage, asset tangibility, asset risk, stock liquidity, as well as country and day fixed effects, since the regression uses firm-day observations. For brevity, we present the coefficient estimates only for the MNC dummy, the stringency index, and their interactions.

The results presented in Panel A suggest that stronger, more decisive government action during the crisis period triggers larger stock price declines. For four of the five overall indices (Panel A2), stringency variables load negatively and significantly, consistent with the view that strict government interventions and lockdowns may represent a trade-off between short-term negative economic shock and prolonged spread of the virus. The interactions also reveal that MNCs in countries with more stringent measures experience greater declines in stock prices than DCs. On average, MNCs located in more stringent countries (as measured by the overall stringency indices in Panel A2) fare incrementally worse (1.2%) relative to DCs. Turning to individual stringency indicators (Panel A1), restrictions on international travel have the greatest impact, amplifying the MNC–DC performance gap by 1.2%, followed by school closing (1.1%), workplace closing (0.9%), restrictions on gatherings (0.8%), and public information campaigns (0.8%).

Panel B of Table 5 replicates the analyses using post-crisis returns as the dependent variable. In sharp contrast to the stock price response during the crisis period, we do not find strong evidence that stringency negatively impacts stock prices in the post-crisis period. This holds except for international travel controls (− 0.7%) and international support (0.0%), whose impacts are smaller than those observed during the crisis period (with international support effectively negligible). Moreover, in contrast to the results found in Panel A, we see that some aspects of stringency can actually have a positive impact in the post-crisis period, as evidenced by the impact of income support (1.9%), restrictions on gatherings (1%), and school closing (1%), all of which may be evidence for short-term pain for long-term gain. Results for the interactions between MNC and the overall stringency indices load positively and significantly for three of the five indices. These results support the notion that stringency in government response causes short-term pain for long-term gain. This is also consistent with what we have witnessed about the stock market behavior relative to the real sector in the post-crisis return period. There was an apparent decoupling of the continued decline in real sector outcomes (e.g., employment) and stock market recovery. It turns out that this is entirely rational because stock markets are forward-looking and capitalize on the long-term benefits of these stringency measures.

How Is a Pandemic-Born Crisis Different?

The vast majority of crises over the last 100 years were born of financial causes. Fragility in financial systems, whether in banking or currencies, caused local pain in countries or regions. Historically, internationalization has offered some benefits to MNCs during both crisis and recovery periods. Consistent with a portfolio diversification theory, having “assets” in different areas can help MNCs weather financial hardships in their domicile nations or regions.16 This benefit can flow through financial and real aspects of the firm (Errunza & Senbet, 1981; Gande et al., 2009). Internationalizing financial aspects of the firm is beneficial when the domestic financial system is dysfunctional, or even shuts down. Internationalizing real aspects of the firm is beneficial when the nonfinancial aspects of the firm involving, for example, supply and/or demand, are limited or depleted domestically.

The pandemic-induced crisis is different primarily in its sheer scope. The international resources for firms facing this crisis in their domestic country or region may no longer be available. Moreover, as we have observed, firms can be impacted economically even before the pandemic hits their nations (or after the worst of the pandemic has passed) due to differences in crisis periods, government responses, as well as being economically linked with regions or countries that have been hit by the pandemic. For instance, the economies of African countries were adversely affected even before the virus showed up on their shores due to linkages with China, EU, and the U.S.

We examine real and financial factors that have moderating effects on the impact of the pandemic on firms, with a focus on MNCs, during the crisis and post-crisis periods. Following the approach in Table 5, in Table 6 we regress the returns for crisis and post-crisis periods on an MNC indicator, various real and financial factors, and interactions of the MNC indicator with these factors. Panel A displays the results for the impact of real factors in the crisis period.17 Significantly negative coefficients (except for Model 2, which we discuss subsequently) on the interaction terms suggest that real aspects of MNCs can exacerbate their negative crisis returns. The first three models speak to the impact of having more international customers and/or an international supply chain. The coefficients suggest that this internationalization factor is detrimental during the crisis for MNCs from countries that primarily produce goods (Model 1) as opposed to services (Model 2). Consistent with this notion, the coefficients on the interaction terms in Models 1 and 3 are negative and significant, while that in Model 2 is positive and significant. Collectively, these results imply that the effect stems from the production and/or transportation of goods alone, hence supporting the notion that MNC underperformance stems from a supply chain adverse impact.

Models 4–6 speak to the human capital of the firm, which is, on average, much larger for MNCs. The negative coefficient on the interaction term associated with the employment growth variable in 2019 may be reflective of the negative impact of underutilization of the workforce during the pandemic. Moreover, money spent training employees pre-pandemic is ultimately less money the firm can spend on transitioning business to pandemic operations. Finally, the negative impact of women with degrees on MNC performance is intuitive because women absorb the brunt of the additional childcare needs when schools are shut down (Stevenson, 2021). Many women decided to leave the workforce in 2020 in response to school closures. Women with degrees, who are more likely to have managerial positions that were not eliminated due to the pandemic, were forced to do their jobs while helping children navigate distance learning. During school closures, productive hours were diminished or even lost completely.

Models 7 and 8 speak to investment in infrastructure prior to the crisis. The statistically significant negative impacts of both investment in research and development (R&D) and gross fixed capital formation may seem surprising until we remember the complete shutdown that happened in many countries. Again, this reflects the market’s downward adjustment in the valuation associated with investment in infrastructure and R&D that happened in 2019, with the pandemic shock perturbing the investment path. Moreover, given the footprints of international firms, they are more likely than DCs to be impacted due to exposure to international customers and suppliers. The impact is also likely to last longer because of exposure to countries that are hit by the pandemic both before and after their domicile nation. In these cases, capital spent on R&D and/or gross fixed capital prior to 2020 is less capital available to endure the shutdown and shift major aspects of their businesses online. To make matters worse, we know that major transitions hit large MNCs much harder than DCs.

Panel B provides an analysis of various aspects of the MNCs’ domicile countries along a financial dimension. In contrast to what is usually true with financial crises (for example, the Great Recession), financial aspects of the domicile nation represent a mitigating effect on crisis returns. Models 1–5 suggest that larger stock markets, deeper capital markets, greater foreign investor interest, state ownership that does not pose a threat to the business world, and a larger venture capital industry are associated with less negative crisis returns. Models 6 and 7 suggest that greater access to credit (from whatever source) is likewise important. Adding some depth to these results, we see that the main effect on these financial factors, which represents their effect on DCs (where MNC = 0), is largely negative and, in four of the five models, statistically significant. This suggests that the benefit ascribed to MNCs in this case is not universal to all firms. It could be that even though the global financial industry was relatively strong going into the crisis, it catered to larger firms, which are perceived as more creditworthy. This is consistent with the large number of “main street” firms, for example, in the restaurant industry, that went bankrupt during the pandemic.

Panels C and D of Table 6 examine the moderating effects of the real and financial factors in the post-crisis period. The intuition underlying this analysis is as follows. As discussed above, the negative coefficients loading on the real factors in Panel A may be attributable to the market’s adjustments in expectations for firm valuation as the result of the severe event. It is, therefore, instructive to examine whether there are reversals as we move from the stock return crisis period or whether this is a new normal to be sustained for an indefinite future. Turning first to Panel C, we observe that the vast majority of interaction terms show a positive effect (save for Models 1 and 2, the latter of which should be negative if the effect reverses from Panel A) and, in two cases, statistically significant impact. This suggests that the majority of these real factors, which were liabilities during the crisis, are no longer hindering MNC performance in a disproportionate way post-crisis. This is an improvement from the results in Panel A. It is noteworthy, though, that these factors, which typically contribute significantly to MNC value, are mostly insignificant drivers of MNC value during our post-crisis period.

The results in Panel D are similar to those in Panel C in two ways. First, these results likewise suggest there is only marginal importance of the factors in the post-crisis period. Second, most of the coefficients have switched signs from the results in their crisis period counterpart. Specifically, we note that five of the seven interaction term coefficients in Panel D have negative coefficients, and two of them (Models 2 and 3) are statistically significant. The results in Models 2 and 3 may reflect the composition of foreign investment (beyond level) with a portfolio investment component being more susceptible to flight to quality.

Collectively, the results in Table 6 suggest there are limits to the benefits of globalization. While ample work has documented the benefits of globalization through the valuation effects of multinationality, our study suggests that these are limited, or even reversed, during a pandemic-induced crisis of COVID-19 proportions. This pandemic has brought to light the dark side of globalization. More specifically, during this tail event, our results suggest that dimensions of an MNC that are considered mitigating (exacerbating) effects in financial crises are actually exacerbating (mitigating) effects in the global pandemic.

The marginal reversal of results for real and financial factors of MNCs post-crisis, combined with the unique impact of these factors during the crisis, is somewhat puzzling. Thus, while it is comforting that the negative impact was short-lived (though these factors fall shy of returning to a positive driver of firm performance in our post-crisis period), it is important to understand more fully why real factors become a liability to MNCs during a pandemic.

Moderating Effects of the Real and Financial Factors on MNC Performance Under Government Stringency

A major source of uncertainty throughout the crisis has been the wisdom of certain government responses. As noted in Table 5, the severity of the government response in an MNC’s domicile nation impacts how negative its crisis returns are. We next combine the implications of this finding with the real and financial factors of internationalization analyzed in Table 6. We examine the impact of real and financial aspects of MNCs in countries based on a threshold median value. Thus, specific government responses will be identified as being higher or lower than the median value. This allows us to gain some insight into whether the government response played a role in the unique impact of real and financial factors on crisis returns during the pandemic.

Table 7 provides the results of this analysis. Panels A1 and A2 show the results for interaction terms between MNC and the same real factors examined in Table 6, Panel A. This analysis differs from Table 6 in two key ways. First, it uses firm-day observations because government stringency data are provided daily. Second, it bifurcates the sample by the median government responses. Panel A1 (Panel A2) displays results for the crisis period using firm-day observations that exist in countries that respond with greater (less) than the median threshold. For brevity, Table 7 displays these findings using only the index focused on the closure and containment restrictions, which is the Legacy Stringency Index. We choose this index because the broadest indices include features of government response that may have positive impacts on stock returns, such as economic support (Aharon & Siev, 2021; Ashraf, 2020) and COVID testing policies, the ambiguity of which makes the results more difficult to interpret. The results using the second most focused index are in “Appendix B” and are similar.18

The results in Panel A1 are largely consistent with those found in Table 6, Panel A, with six of the seven factors statistically significant. By way of contrast, the results in Panel A2 are all insignificant, with two of the seven models switching signs (though Model 6 lacks meaningful results). Collectively, the results in Panels A1 and A2 are consistent with the idea that the stringency of the government response is partly responsible for the real factors becoming a liability during the crisis period. Anecdotally, this novel evidence makes a lot of sense. When countries shut down their borders – or even the companies themselves – to contain a virus, real factors, such as supply chains, transportation of goods, and physical productivity, face additional hurdles. The subsample analyzed in A2 represents firms located in countries whose governments react less stringently, which impacts those real factors less significantly.