Abstract

In the preceding Part 1 of this two-part paper, I set out the background necessary for an understanding of the current status of the debate surrounding the relationship between science and religion. In this second part, I will outline Ian Barbour’s influential four-fold typology of the possible relations, compare it with other similar taxonomies, and justify its choice as the basis for further detailed discussion. Arguments are then given for and against each of Barbour’s four models: conflict, independence, integration and dialogue. In contradiction of the recent trend to dismiss the conflict model as overly “simplistic”, I conclude that it is the clear front-runner. Critical examination reveals that theology (the academic face of religion) typically proceeds by first affirming belief in God and then seeking rationalisations that protect this belief against contrary evidence. As this is the very antithesis of scientific endeavour, the two disciplines are in unavoidable and irreconcilable conflict.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Namely, the prominent “New Atheists” Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris and Christopher Hitchens: See Part 1.

The classic and decisive refutation of the argument from design is due to Dawkins (1986).

Recall too from Part 1 Wittgenstein’s influential family-resemblance analogy, according to which there may be no necessary and sufficient conditions for category membership, yet the categories are nonetheless valid and useful.

Note the assumption that there is a distinctive and valid “religious way of reasoning”, which is contrary to our conclusion in Part 1 of this two-part article.

A quote widely attributed to Albert Einstein is: “Only two things are infinite, the universe and human stupidity, and I’m not sure about the former”.

As Peters puts it: “The question of God is no longer a religious question; it is a scientific one”.

Tyson has been at great pains to stress that he is agnostic, and essentially uninterested in matters of religion.

I am sure CMI adherents would dissent vigorously from this characterisation, to which my response would be that “concrete” and “meaningful” would have to mean different things to them and to me. The stock example given is that quantum indeterminancy makes room for divine action. But not only is quantum indeterminancy still not fully understood in agreed-upon fashion by physicists, thus making a shaky foundation on which to try to ground a theology, the vague notion of “making room for God” is a far cry from religion offering a useful pointer for scientific research, as CMI would claim the ability to do as part of its raison d’être.

Note the similarity here with the division into “matters of fact” and “relations of ideas” (i.e., Hume’s fork) as mentioned in Part 1.

It is difficult to be definitive on this as the religious beliefs—or otherwise—of many scientists remain private to them. Also, individual scientists may well be identified as, e.g., Jewish or Christian, purely on the grounds of family background, while either having little or no adherence to Jewish or Christian belief, or having rejected it.

It has to be said that, in the hands of theologians highly prone to take the existence of God as a given on the basis of faith, the two flavours of theology have an inevitable tendency to conflate. That is, the majority of theologians are seemingly unable to look dispassionately at the scientific evidence for the existence of God (no doubt because there isn’t really any) without lapsing into ab initio acceptance of the very thing that is at issue, i.e., God’s existence.

That is, due to Thomas Aquinas.

Recall from Sect. 3 that this is Barbour’s preferred model.

“Retreat to the possible” is a form of rhetoric often employed by apologists in which it is held that if something is logically possible, no matter how unlikely, and it has not been definitively refuted, then it has to be taken seriously as a valid belief independent of the evidence for or against it. The more rational position, and that held by scientific naturalists, is that the strength of belief in a proposition like the resurrection should be proportional to the strength of the evidence for it, i.e., virtually zero.

His examples are actually presuppositions of religion rather than of science, but let us be charitable and allow that dialogue is two-way.

In fact, based on their respective track records of providing answers to deep questions about the universe and its workings, religion is far less well equipped than science in this regard.

Systematic theology is a form of the discipline that abstracts themes from across scripture and organises them under headings. For example, eschatology is to do with end-times and afterlife, Christology is the study of the nature of Jesus, his divinity, his life, his teachings, etc., soteriology is concerned with the doctrine of salvation, and so on. Having organised themes in this way, one can proceed to study the way that they relate to one another. Systematic theology contrasts with biblical theology, in which the various books of the Bible are taken as a whole, and contrasted with one another. To a physical scientist like myself, the apparent need to preface the name of a discipline with the qualifier “systematic” is a pointer to its lack of inherent systematicity. After all, “systematic physics” would be something of a tautology.

John Templeton himself provides some insight into this intent with the quote: “All of nature reveals something of the creator. And god is revealing himself more and more to human inquiry, not always through prophetic visions or scriptures but through the astonishingly productive research of modern scientists.” Source: https://www.templeton.org/about/sir-john, last accessed 24 January 2022.

... with the award of the Templeton Prize, whose value (in an apparent attempt to buy esteem for the notion of science-religion dialogue with his extravagant wealth) substantially exceeds that of a Nobel Prize.

Science is simply too strong an opponent for most careful, educated religionists to be reckless enough to pick a fight with it.

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/a-scientific-defense-of-t_b_523416, last accessed 25 January 2022.

http://www.issacharfund.org/, last accessed 25 January 2022.

In the interests of fairness, I should mention that atheist organisations sometimes sponsor books too, although relatively rarely. An example is Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus, part-funded by Atheists United. Of course, one should maintain a similarly open-minded attitude to appraising these.

This is my own example, not mentioned by Coyne, although it might as well have been.

Coyne does not mention my favourite comical Old Testament stricture: Leviticus 19:27, “You shall not shave around the sides of your head, nor shall you disfigure the edges of your beard” (New King James Version), which vividly illustrates the depths of stupidity to which the Bible is capable of sinking. I will never forget my first visit to Israel in 1984 when I discovered to my utter amazement that large numbers of contemporary Orthodox Jews actually took this craziness seriously and acted accordingly. Do they not think their God has more important things to concern him than their shaving habits? Note too the presumption that all of God’s people are male.

Not to mention religious wars, inquisitions, burnings at the stake, etc.

References

Baggini, J. (2016). The Edge of Reason: A Rational Skeptic in an Irrational World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Barbour, I. G. (1990). Religion in an Age of Science: The Gifford Lectures (Vol. 1). HarperSanFrancisco.

Barbour, I. G. (1997). Religion and Science: Historical and Contemporary Issues. HarperSanFrancisco.

Barbour, I. G. (2000). When Science Meets Religion: Enemies, Strangers or Partners? HarperSanFrancisco.

Barbour, I. G. (2008a). Taking science seriously without scientism: A response to Taede Smedes. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 43(1), 259–269.

Barbour, I. G. (2008b). Remembering Arthur Peacocke: A personal reflection. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 43(1), 89–102.

Barzhagi, A., & Corcó, J. (2016). Stephen Jay Gould and Karl Popper on science and religion. Scientia et Fides, 4(2), 417–436.

Black, M. (1964). The gap between "is" and "should". The Philosophical Review, 73(2), 165–181.

Bloom, P. (2012). Religion, morality, evolution. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 179–199.

Boudry, M. (2013). Alvin Plantinga: Where the Conflict Really Lies. Science, Religion, and Naturalism. Science & Education, 22(5), 1219–1227. Book Review of Plantinga, 2011.

Boudry, M., & Pigliucci, M. (Eds.). (2018). Science Unlimited? The Challenges of Scientism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Brooke, J. H. (1991). Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, A. (1999). The Darwin Wars: The Scientific Battle for the Soul of Man. London, UK: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

Bschir, K., Lohse, S., & Chang, H. (2019). Introduction: Systematicity, the nature of science? Synthese, 196(3), 761–773.

Cantor, G., & Kenny, C. (2001). Barbour’s fourfold way: Problems with his taxonomy of science-religion relationships. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 36(4), 765–781.

Carrier, R. (2014). On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason to Doubt. Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Collins, F. S. (2006). The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief. New York, NY: Free Press.

Coyne, J. A. (2009). Why Evolution is True. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Coyne, J. A. (2015). Fact versus Faith: Why Science and Religion are Incompatible. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Darwin, C. (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.

Dawes, G. W. (2019). Galileo and the Conflict Between Religion and Science. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Dawkins, R. (1986). The Blind Watchmaker. Harlow, UK: Longman.

Dawkins, R. (2006). The God Delusion. London, UK: Transworld Publishers.

Deane-Drummond, C. (2009). Christ and Evolution: Wonder and Wisdom. London, UK: SCM Press.

Dennett, D. C. (1995). Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life. London, UK: Penguin.

Dennett, D. C. (2006). Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. New York, NY: Viking.

Draper, J. W. (1875). History of the Conflict Between Religion and Science. New York, NY: D. Appleton & Co.

Eddy, M. D., & Knight, D. (2006). Introduction to Oxford World Classics paperback reprint of William Paley’s Natural Theology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Eldridge, N. (2000). The Triumph of Evolution and the Failure of Creationism. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gill, J. H. (1965). Reviewed Work: Models and Mystery by Ian T Ramsey. The Philosophical Review, 74(4), 550–553.

Gingerich, O. (2014). God’s Planet. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gingras, Y. (2017). Science and Religion: An Impossible Dialogue. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. (Translated from the original 2016 French version by Peter Keating.)

Gould, S. J. (1997). Nonoverlapping magisteria. Natural History, 106(2), 16–22.

Gould, S. J. (1999). Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Gragg, A. (1966). Paul Tillich’s existential questions and their theological answers: A compendium. Journal of Bible and Religion, 34(1), 4–17.

Hardin, J., Numbers, R. L., & Binzley, R. A. (Eds.). (2018). The Warfare Between Science and Religion: The Idea That Wouldn’t Die. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Harrison, P. (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Haught, J. F. (1995). Science and Religion: From Conflict to Conversation. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Haught, J. F. (2008). God and the New Atheism: A Critical Response to Dawkins, Harris and Hitchens. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press.

Hawking, S. (1988). A Brief History of Time. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Holland, T. (2019). Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind. London, UK: Little, Brown.

Howard Ecklund, E., & Scheitle, C. P. (2017). Religion vs. Science: What Religious People Really Think. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hoyningen-Huene, P. (2013). Systematicity: The Nature of Science. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hutchinson, I. (2011). Monopolizing Knowledge: A Scientist Refutes Religion-Denying. Belmont, MA: Fias Publishing.

Jesse, J. G. (2006). Mapping the unmappable geography: Teaching religion and science. American Journal of Theology and Philosopy, 27(2/3), 225–246.

Lennox, J. C. (2019). Can Science Explain Everything? Epsom, UK: The Good Book Company.

Lightman, B. (2018). The Victorians: Tyndall and Draper. In J. Hardin, R. L. Numbers and R. A. Binzley (Eds.), The Warfare Between Science and Religion: The Idea that Wouldn't Die (pp. 65–83). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lineweaver, C. H. (2008). Decreasingly overlapping magisteria of science and religion. In J. Seckbach & R. Gordon (Eds.), Divine Action and Natural Selection: Science, Faith and Evolution (pp. 155–170). Singapore: World Scientific.

Lonergan, B. J. F. (1972). Method in Theology. New York, NY: Herder & Herder. (Pagination refers to 2007 University of Toronto Press paperback edition.)

McGrath, A. (2007). The Dawkins Delusion? Atheist Fundamentalism and the Denial of the Divine. London, UK: SPCK Publishing. (With Joanne Collicutt McGrath.)

McGrath, A. E. (2004). The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Michalski, R. S. (1983). A theory and methodology of inductive learning. In R. S. Michalski, J. Carbonell, & T. M. Mitchell (Eds.), Machine Learning: An Artificial Intelligence Approach (Vol. 1, pp. 83–134). Palo Alto, CA: Tioga Press.

Moritz, J. M. (2009). Rendering unto science and God: Is NOMA enough? Theology and Science, 7(4), 363–378.

Neisser, U. (2014). Cognitive Psychology: Classic Edition. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

Numbers, R. L. (Ed.). (2009). Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Orr, M. (2006). What is a scientific worldview, and how does it bear on the interplay of science and religion? Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 41(2), 435–444.

Paine, T. (1794). The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology. Paris, France: Barrois.

Paley, W. (1802). Natural Theology: or, Evidence of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity, Collected from the Appearances of Nature. Philadelphia, PA: John Morgan.

Peacocke, A. (1986). God and the New Biology. London, UK: Everyman.

Peacocke, A. (1993). Theology for a Scientific Age: Being and Becoming—Natural, Divine and Human. Second edition. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press.

Pedersen, O. (1983). Galileo and the Council of Trent: The Galileo affair revisited. Journal of the History of Astronomy, 14(1), 1–29.

Peters, T. (2018). Science and religion: Ten models of war, truce and partnership. Theology and Science, 16(1), 11–53.

Pigliucci, M. (2010). Nonsense on Stilts: How to Tell Science from Bunk. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Plantinga, A. (2000). Warranted Christian Belief. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Plantinga, A. (2011). Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (1986). One World: The Interaction of Science and Theology. London, UK: SPCK Publishing.

Polkinghorne, J. (1991). Reason and Reality. Philadelphia, PA: Trinity International Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (1995). Serious Talk: Science and Religion in Dialogue. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International.

Polkinghorne, J. (1998). Belief in God in an Age of Science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Polkinghorne, J. (2000). Faith. Science and Understanding. London, UK: SPCK Publishing.

Popper, K. (1935). Logik der Forschung: Zur Erkenntnistheorie der modernen Naturwissenschaft. Julius Springer, Vienna, Austria. (English language rewrite The Logic of Scientific Discovery published by Routledge, Abingdon, UK in 1959.)

Ramsey, I. T. (1957). Religious Language: An Empirical Placing of Theological Phrases. London, UK: SCM Press.

Ramsey, I. T. (1964). Models and Mystery. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Rees, M. (2001). Just Six Numbers: The Deep Forces that Shape the Universe. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Rosch, E., & Lloyd, B. B. (Eds.). (1978). Cognition and Categorization. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ruse, M. (2000). Can a Darwinian be a Christian? The Relationship between Science and Religion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Ruse, M. (2008). Evolution and Religion: A Dialogue. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Russell, B. (1935). Religion and Science. London, UK: Butterworth Thornton Ltd.

Russell, R. J., & Ian, G. (2017). Barbour’s methodological breakthrough: Creating the bridge between science and religion. Theology and Science, 15(1), 28–41.

Sagan, C. (1996). The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. New York, NY: Ballantine Books.

Shermer, M. (1997). Why People Believe Weird Things — Pseudo-science, Superstition and Bogus Notions of Our Time. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Shermer, M. (2017). Scientific naturalism: A manifesto for enlightenment humanism. Theology and Science, 15(3), 220–230.

Slattery, J. P. (2019). Science and religion: An impossible dialogue. Politics, Religion and Ideology, 20(3), 381–383. Book Review of Gingras, 2017.

Smedes, T. A. (2008a). Beyond Barbour or back to basics: The future of science-and-religion and the quest for unity. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 43(1), 235–258.

Smedes, T. A. (2008b). Taking theology and science seriously without category errors: A response to Ian Barbour. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science, 43(1), 271–276.

Stenger, V. J. (2007). God: The Failed Hypothesis — How Science Shows that God does not Exist. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Stenger, V. J. (2011). The Fallacy of Fine-tuning: Why the Universe is not Designed for Us. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Stenmark, M. (1997). What is scientism? Religious Studies, 33(1), 15–32.

Stenmark, M. (2004). How to Relate Science and Religion: A Multidimensional Model. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Tillich, P. (1951). Systematic Theology (Vol. 1). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tillich, P. (1957). Systematic Theology (Vol. 2): Existence and the Christ. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Tillich, P. (1963). Systematic Theology (Vol. 3): Life and the Spirit. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Trivers, R. L. (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35–57.

Tversky, A. N., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Tyson, N. deGrasse. (2003). Holy wars: An astrophysicist ponders the God question. In P. Kurtz & B. Karr (Eds.), Science and Religion: Are They Compatible? (pp. 73–79). Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Urban, W. M. (1938). Elements of unintelligibility in Whitehead’s metaphysics. Journal of Philosophy, 35(23), 617–637.

van den Brink, G. (2019). How theology stopped being Regina Scientiarum–and how its story continues. Studies in Christian Ethics, 32(4), 442–454.

van Huyssteen, J. W. (1998). Duet or Duel? Theology and Science in a Postmodern World. London, UK: SCM Press.

van Huyssteen, J. W. (1999). The Shaping of Rationality: Toward Interdisciplinarity in Theology and Science. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans.

Walton, D. N. (2008). Informal Logic: A Pragmatic Approach (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

White, A. D. (1896). A History of the Warfare of Science and Theology. London, UK: Macmillan.

Whitehead, A. N. (1929). Process and Reality: An Essay in Cosmology. New York, NY: The Free Press.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. London, UK: Macmillan. (Translated from the original German by Elizabeth Anscombe).

Worrall, J. (2004). Science discredits religion. In M. Peterson and R. J. VanArragon (Eds.), Contemporary Debates in the Philosophy of Religion (pp. 59–71). Oxford, UK: Blackwell. First edition.

Zanatta, A., Zampieri, F., Basso, C., and Thien, G. (2017). Galileo Galilei: Science vs. faith. Global Cardiology Science & Practice, 10(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.21542/gcsp.2017.10, last retrieved 3 February 2021.

Zuersher, B. (2014). Seeing through Christianity: A Critique of Beliefs and Evidence. Bloomington, IN: Xlibris

Acknowledgements

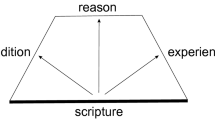

I am grateful to Keith Ward and John H. Brooke for taking the time to reply with commendable good grace to several questions that I posed to them during the writing of this paper. I am indebted to Chang In Sohn of the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (CTNS), Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, CA, who kindly supplied original copy for Fig. 3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Damper, R.I. Science and Religion in Conflict, Part 2: Barbour’s Four Models Revisited. Found Sci (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-022-09871-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-022-09871-z