Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic had an unequal impact across businesses and communities and rapidly accelerated digital trends in the economy. What role, then, did website use play in community resilience and small business outcomes? This article examines a new source of population data on domain name hosts to provide a unique measure of digital economic activity within communities. Seventy-five percent are commercial, including online-only, brick-and-mortar, small, and microbusinesses. With geolocated data on 20 million US domain name hosts, we investigate how their density (per 100 people) affected economic outcomes in the nation’s largest metros during the pandemic. Using monthly time series data for the 50 largest metropolitan areas, the domain host data is merged with the US Census Small Business Pulse Surveys and Chetty et al.’s Opportunity Insights data. Results indicate metros with higher concentrations of businesses with an online presence experienced more positive economic perceptions and outcomes from April to December 2020. This high-frequency, granular data on digital economic activity suggests that digitally enabled small and microbusinesses played an important role in local economic resilience and demonstrates how commercial data can be used to generate new insights in a fast-changing environment.

Plain English Summary

New data show websites were a resource for small business and community resilience in Covid-19. While some studies have shown how digital technologies helped businesses during the pandemic, little research has examined how website use during this time affected communities and their small businesses. Data on the number of domain name hosts (per 100 people) provides a measure of the prevalence of website use in a community. Seventy-five percent of these domain name sites are commercial, primarily small, and microbusinesses. We examine economic outcomes for the 50 largest metros from April to December 2020, including credit and debit card spending, small business revenues and openings, and the perceptions of small business owners. With monthly data and across multiple measures, we find that this digital economic activity positively affected the resilience of communities and small businesses. These findings suggest that policies for an inclusive and effective recovery should consider support for digital skills and effective website use for small and microbusinesses.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The coronavirus pandemic that began in 2020 has been described as a crisis that has little precedent: a rapid disruption, a transformation, a recovery without a template (Long, 2021). One of the undisputed impacts of this crisis was the rapid growth of e-commerce (Koetsier, 2020) and accelerated digital transformation of the economy (Belitski et al., 2021). Digital technologies were a potential resource for adaptation and survival, including for small and microbusinesses. By August 2020, the Small Business Pulse Survey, conducted by the US Census, reported that 25% of respondents had increased their online activity (Kost, 2020). But small businesses suffered disproportionately during the pandemic (Bartik et al., 2020; Fairlie, 2020), which has also had uneven impacts across sectors and metropolitan regions (Parilla et al., 2020). To what extent has website use contributed to small business resilience in communities, and what role might it play in economic recovery? This study tests whether this digital economic activity in a metropolitan region contributed to community resilience, including better outcomes for small businesses during and after the initial shock of the shutdowns.

Also without precedent was the extent to which researchers and policymakers sought new sources of data to understand the crisis through outbreaks and surges. This has included the collection and analysis of massive amounts of data from credit cards, Google searches, mobile devices, social media, and financial services and payroll companies (CardFlight.com; Safegraph.com; Ungerer & Portugal, 2020). In this evolving context, real-time information has filled a void, and we leverage another example of commercial data to understand the digital resilience of small businesses in regional economies.

Drawing on 20 million domain name hosts and their redirects in the USA updated monthly, we examine their geographic distribution as an indicator of the digital economic activity of small and microbusinesses throughout the pandemic. We ask how this activity affected economic outcomes in the nation’s largest metropolitan areas.

The density of these domain name sites represents a measure of participation in the digital economy for communities. Domain names may be used by businesses, nonprofits, or individuals, yet as we will show, at least 75 percent are for commercial purposes, and only 8% have 10 employees or more. Existing government data measure e-commerce transactions but fail to capture broader website/email/social media uses for marketing by brick-and-mortar businesses, gig work, and more. Thus, this data includes a greater diversity of commercial technology uses in local economies, including for microbusinesses.

This study analyzes the population of digital businesses using active domain name hosts (for websites/SSL/email) and their redirects, representing over half of all US domain name hosts. Through collaboration with GoDaddy, the world’s largest registrar of domain names, the researchers gained access to de-identified monthly customer data on these domain hosts in 2020. Using customer-provided zip codes, the data are geocoded and aggregated to the 30,000 + inhabited zip codes. For the purposes of this study, the zip code data is then aggregated to metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) and divided by the population to create a density measure for the fifty largest MSAs in the USA.Footnote 1 Estimates of the population of domain hosts obtained from machine learning or web crawlers may miss domain hosts used for email, encryption (SSL), or business uses for other purposes, as well as descriptions in other languages. In contrast, these data are the full population of domains for the largest provider in the USA.

The granularity and high frequency with which this customer data is collected provides an especially dynamic view of commercial websites during the public health crisis. This is critical for an examination of the role of this activity for urban economic resilience, which is context-specific and takes place over time (Belitski et al., 2021; Pozhidaev, 2021). We pair these data on the density of domain name websites with metro level business and consumer outcomes measured with high-frequency data collected during the pandemic by the Census Small Business Pulse Surveys and Opportunity Insights. While data on this digital economic activity is available for all 952 micropolitan and metropolitan statistical areas, data to measure economic outcomes during the pandemic are only available for the 50 largest MSAs. Yet these 50 MSAs account for 53% of the total US population. These metros span different geographic regions and economic conditions and represent the lion’s share of the nation’s economic activity. Trends in these metropolitan areas are therefore crucial for national economic recovery (Liu, 2021). Given the transformative changes that occurred during the pandemic disruption (Belitski et al., 2021), outcomes from digital activity in small and microbusinesses have implications for how inclusive recovery and growth will be across these communities.

We begin by discussing the unequal effects of the pandemic across firms, industries, and communities. Next, we discuss concepts of resilience, how websites might affect resilience for small businesses, and the role of metropolitan economies as local ecosystems. This is followed by discussion of the potential of large-scale, commercial, and high-frequency data for understanding economic policy issues in real-time, including the data on domain name hosts that provide the foundation for the analysis undertaken here. We analyze the metropolitan-level impacts of domain name websites on local economic activity such as credit and debit card spending and small business revenues, openings, and owner perceptions over the course of the pandemic across US metros. Using monthly data, lagged panel multivariate regression models, and multiple indicators, results show that metros with higher concentrations of these digitally enabled businesses fared better during the crisis, and small businesses were more resilient as well in these places. The conclusion considers implications for future economic development.

2 Uneven impacts of the Covid recession

The coronavirus pandemic not only introduced a novel virus, but a novel economic recession with rapidly changing and varied impacts across industries, regions, and demographic groups. Despite small business relief made available by the federal CARES Act in April 2020, economic recovery during 2020 was slow. As of April 2021, all but two states were below pre-pandemic February 2020 employment levels, with job losses in 27 states still greater than during the Great Recession of 2008 (Ettlinger & Hensley, 2021).

While some sectors were able to transition operations to a remote environment to facilitate social distancing and shutdowns, restrictions caused a major economic shock for industries that rely on in-person interactions and foot traffic. These included hospitality, entertainment, arts, tourism, restaurants, transportation, construction, retail, and personal services (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020; Bartik et al., 2020; Fairlie, 2020).

It was small businesses that were particularly vulnerable during this crisis due to their limited cash on hand (Bartik et al., 2020) and their overrepresentation in the most disrupted sectors (OECD, 2020). At the outset of the pandemic, an estimated 54% of small businesses were in immediate- or long-term risk, accounting for nearly 48 million jobs. Seventy percent of those businesses at risk were the smallest enterprises, or microbusinesses, with fewer than 10 employees (Parilla et al., 2020). The number of active business owners dropped 22% between February and April 2020, the largest decline on record (Fairlie, 2020). According to Yelp’s Local Economic Impact Report, over 160,000 businesses reported temporary or permanent closures between March and September 2020, with most closures in the restaurant, retail, and beauty industries (Yelp, 2020).

The economic impact of the pandemic not only varied by sector and region, but across demographic groups. These effects have been acutely felt among businesses owned by women and people of color (Fairlie, 2020; Kramer Mills & Battisto, 2020; Manolova et al., 2020). Based on microdata from the Census and Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Current Population Survey at the height of the first wave pandemic (February–April 2020), Fairlie found that active business owners dropped 41% for Blacks, 32 percent for Latinos, and 26 percent for Asian-Americans, in contrast with 17% for non-Hispanic whites. Though these more vulnerable businesses were concentrated in the sectors most affected by the shutdowns, Fairlie, (2020) showed that size accounted for more of this decrease, with smaller firms less able to make rapid changes. Women-owned businesses were also hit hard, as they had lower revenues and profits on average (Fairlie, 2020) and were concentrated in highly impacted sectors (Loh et al., 2020; Manolova et al., 2020).Footnote 2

In contrast with prior recessions, however, new business registrations also soared during 2020, potentially as a response to unemployment and stimulus payments (O’Donnell et al., 2021). This included increases in business starts in zip codes with higher proportions of Black residents (Fazio et al., 2021). An online presence may have been one factor sustaining businesses or facilitating new startups during the pandemic. The next section examines research on resilience and how commercial websites may have influenced the ability of businesses and communities to absorb the Covid-19 shock, respond, and take steps toward recovery.

3 Defining resilience

The concept of resilience originates in the study of ecological systems but has been applied more recently to social systems, including communities (Matarrita-Cascante et al., 2017; Wilson, 2012). Resilience describes the ability to respond to and recover from a system disruption, or “the ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to, transform and recover” in the face of exogenous shocks (Noy & Yonson, 2018, 2). Used across disciplines, resilience has been studied in community-level research on disaster management and in urban economies (Pozhidaev, 2021). Thus, resilience may be examined at multiple scales, including for businesses and the communities in which they are established.

Certain capacities (Norris et al., 2008) or resources (Magis, 2010) may facilitate resilience, but resilience takes place over time (Belitski et al., 2021) and is contextual depending on the nature of the disruption, the actions taken to manage the impact of the disruption, and complex relationships within systems (Magis, 2010; Matarrita-Cascante et al., 2017; Pozhidaev, 2021). Though resilience is not determined by capacities or resources, their presence may help to absorb the shock, or they may serve as dynamic capabilities that can be used to adapt or to transform processes (Belitski et al., 2021; Priyono et al., 2020).

A growing body of literature has investigated the impact of different digital technologies for businesses during the pandemic. This includes videoconferencing and social media in the fitness industry (Ananthakrishnan et al., 2020) and digital platforms such as Uber Eats for restaurants (Raj et al., 2020). The United Nations Capital Development fund fielded surveys during the pandemic on technology use for SMEs in least-developed countries (Pozhidaev, 2021), and Google conducted similar surveys of businesses in the USA and Europe (Digitally Driven, 2020, 2021).

Most analysis has examined outcomes for individual businesses, though one study found that higher levels of prior investment in IT by firms predicted lower rates of unemployment in metropolitan areas during the pandemic (Pierri & Timmer, 2020). Similarly, some research has tried to measure local digital economies by the density of domain name hosts for commercial activity. Controlling for other factors, US counties with higher density of this digital economic activity experienced lower rates of monthly unemployment from January 2019 to November 2020, both before and during the pandemic (Mossberger et al., 2021). Additionally, research using statistical matching across all US counties found this density to be a significant predictor of growth of median income, recovery from the 2008 recession, and various measures of economic prosperity (Mossberger et al., 2021). Counties with higher density of domains have stronger labor market outcomes as well (Yu & Bengali, 2021). Previous research has not measured this digital economic activity for metro areas, nor with high-frequency monthly data.

4 How digital economic activity may have aided resilience of small businesses

Most domain name hosts support websites, though some are also dedicated to other digital uses such as email and SSL for encryption. Websites are a widely used digital tool that can contribute to business resilience, including for small businesses or solo entrepreneurs. Dörr et al., (2021) extracted data on business changes due to coronavirus from 1.8 million corporate websites in Germany to examine differences in adaptation across industries. Their study demonstrated that websites were a critical element for many businesses to communicate changes due to the pandemic, facilitating adaptation. Commercial websites lower the cost of communication as well as transaction costs (Greenstein et al., 2018) for both online-only and brick-and-mortar businesses. During an era of business shutdowns and rapid adjustments, businesses could advertise modified hours, reopening, health protocols, virtual appointments or classes, new menus, curbside pickup, and delivery. The searchability of websites and the availability of information around the clock might also enhance discovery by new customers seeking an alternative to businesses that had closed. During times of uncertainty, websites can inform business decisions through data. They can collect feedback from customers through embedded services such as email and links to social media or through data analytics based on sales and site visits. Websites offer a platform for transactions including online sales and contactless payments.

Digital communications and transactions helped businesses to accommodate to their evolving environment and in some cases to fundamentally transform their business processes, as with virtual fitness classes (Ananthakrishnan et al., 2020) and curbside pickup. Businesses that had already acquired websites were better prepared to absorb the shock of the pandemic. Whether through an existing website or the adoption of a new one, business use of sites supported dynamic capabilities for resilience (Belitski et al., 2021; Priyono et al., 2020).

Websites are also a potential resource for recovery. Entrepreneurship grew in the aftermath of the initial shock, with new business starts up 24% in 2020 (O’Donnell et al., 2021). The majority of these new registrations were for non-employer businesses, especially non-store retail (online sales). Starting a business from home, without the need for rent, utilities, and other costs lowers barriers to market entry. Some new businesses or side gigs undertaken during the pandemic may have been a temporary response to unemployment, but they may also have a more lasting impact during the recovery (O’Donnell et al., 2021). Additionally, small, local businesses that adopted websites during the pandemic shutdowns may have been able to expand their markets, and with the lower communication and transaction costs, they may reap new efficiencies, even in brick-and-mortar establishments.

The foregoing discussion of websites is based on their potential to support resilience in individual businesses, but we are interested in exploring the collective effects of the density of these digitally enabled businesses for communities. The concept of resilience is based in systems theory, and resilience could be expected to vary across local economies.

5 How digital businesses in metropolitan regions may have influenced small business resilience

The resilience of small businesses across metros can be viewed through the lens of the local environment. Metropolitan areas, which are defined by the US Census based on commuting patterns and economic integration, represent the regional economies in which these businesses are embedded.

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic differed across these regions. Communities in the Southwest, parts of Texas, and along the Atlantic were among the first to experience the economic impact of the pandemic as business activity in the tourism and service sectors came to a halt in Spring 2020 (Parilla et al., 2020). The largest metros were initially hit hardest in the pandemic, but prospects for recovery and future development are brighter for at least some of these metros — those with a larger share of employment in the technology industry and other knowledge-driven sectors (Muro et al., 2020; Kim & Loh, 2021; Liu, 2021). Despite population losses in some cities during the pandemic, the outflow from some of these “superstar cities” of the IT industry has often been to neighboring counties within the metro area or to other metros such as secondary tech hubs (Muro et al., 2021). One study of the 50 largest metropolitan areas during the last 3 recessions showed that places with more educated populations and more elastic housing markets tended to fare better, though with some differences across recessions (Arias et al., 2016). And while the concentration of the IT industry and educated residents has buoyed economic resilience in the past, the prevalence of technology use across sectors may assist all types of businesses in communities in an era when digital technologies operated as a safety net (Belitski et al., 2021; Digitally Driven, 2020).

The density of digital economic activity represents local networks of digitally enabled businesses, and this may be a critical source of resilience for small businesses. Denser networks could provide a basis for knowledge spillovers, learning, and mentorship within local areas (Andersson & Larsson, 2016). During the pandemic, as technology adopters were able to sustain their businesses (absorb the shock) or use their website in new ways (through dynamic capabilities), places with more websites may have had more opportunities for emulation and learning, contributing to small business resilience in the regional economy.

What previous research leads to is the expectation that digital economic activity should aid in the resilience of metropolitan areas, including for small businesses. Thus, our expectation driving the research is:

A higher density of digitally enabled businesses in metropolitan regions helps mitigate the shock of major crises—such as the Covid-19 pandemic—for small businesses in the area.

6 Research design—cross-sectional monthly time series

This study uses new commercial data collected during the pandemic in 2020 to measure local economies combined with more traditional public data from the US Census through their high-quality random sample surveys.

The density of domain name hosts in metropolitan regions serves as an indicator of digital economic activity in metros. These domain name websites, which organize the underlying address book of the internet (ICANN, 2012), provide platforms for a broad range of internet uses, including e-commerce, online advertising, email, and data analytics. Data on domain name registrations were used to track the geographic diffusion of the commercial internet in metros in early studies (Kolko, 1999; Moss & Townsend, 1997; Zook, 2000). In this study, we have access to more information about these domains beyond their registration.

To measure the resilience of small businesses in metros, empirical evidence from a variety of economic indicators is used (credit card spending, business revenue, and small business openings) with data from Opportunity Insights.Footnote 3 We also include perceptions from small business owners using the large sample Small Business Pulse conducted by the Bureau of the Census.Footnote 4 Both datasets provide monthly time series measures.

Given the monthly structure of the data, we use pooled cross-sectional time series models with panel-corrected standard errors (Beck & Katz, 1996), a form of linear regression that accounts for repeated measures of each metro (MSA) over many months.Footnote 5 Beck and Katz argue that when the number of time periods is less than the number of panels (geographies), panel-corrected standard errors should be used. We specify a panel-specific autoregressive by one period (AR1) process for the pooled cross-sectional time series model, where the panel is a metro. We use time series statistical models to improve causal inferences, ensuring the predictor variable occurs before change in the outcome variable (Box-Steffensmeier et al., 2014). Linear cross-sectional time series with panel-corrected standard errors and AR1 disturbances address time and cross-sectional heterogeneity and yield causal estimates.

The dependent variables measure local economies and small business health with multiple variables from the Opportunity Insights and Small Business Pulse data. The primary explanatory variable is the measure of the density of digital businesses (domain name hosts and redirects) per 100 people for each MSA lagged 1 month prior to measurement of the outcome variable. We also estimate dynamic models using the Opportunity Insights data, lagging the dependent variable 1 month, to more directly measure the impact of digital economic activity on the monthly change in metro economic conditions.

Although we have website density data on all 923 US metropolitan and micropolitan areas, for this study we restrict the sample to match with the outcome variables below, which are only available for the 50 largest metros. See Appendix 1 for a full listing of cities and MSAs included in the analysis.

6.1 Growing use of commercial data

For researchers and policymakers interested in understanding the pandemic and its effects, data from the private sector has been critical for identifying emerging trends. Compared to traditional public data sources, including annual government Census data, commercial data often captures information at a higher frequency and with finer geographic granularity, allowing for more dynamic analysis (Glaeser et al., 2019).

Chetty and his colleagues have taken advantage of private sector data to develop the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker (Chetty et al., 2020). This tool uses anonymized data from several private companies, including credit card processors and payroll firms, to provide a real-time snapshot of important economic indicators such as employment rates, business revenues, and consumer spending during the pandemic recession.

There are other examples of commercial data use for economic research in the past few years, and it has increased prominence for monitoring developments during the pandemic. These include job postings, real estate listings, online transactions, and user activity on platforms such as LinkedIn or Yelp. Most do not specifically focus on small businesses, however, or have limitations for covering subnational geographies.

This burgeoning of high-frequency data is not limited solely to the private sector, however. The Small Business Pulse Survey was created by the US Bureau of the Census to gauge the effect of the pandemic on small business in the USA. Launched in April 2020 and continued into 2022, this large sample survey measures overall business sentiment, operational challenges, financial stress, and expected recovery among small business owners on a weekly basis (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020).

This high-frequency data has not been available for all geographies, but the Small Business Pulse Surveys and Opportunity Insights provide measures for economic outcomes for the largest metropolitan areas, the drivers of the national economy. They are used as primary outcome variables in this study and are discussed in more detail below.

6.2 Dependent variables

To explore the business environment in US metropolitan regions, the dependent variables are drawn from these two sources. The first contains objective statistics from the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker, a non-profit research institute at Harvard University.Footnote 6 Opportunity Insights has a partnership with a number of companies to provide anonymized data, and they collect a variety of measures at different geographic scales (US counties and metros) (Chetty et al., 2020). Credit/debit card spending is from Affinity Solutions, and small business openings and small business revenue are from Womply. These data are collected as 7-day moving averages. However, given the monthly measurement of the domain name host data, we create a monthly mean value from April to December 2020. As the coronavirus shutdowns began in mid-March 2020, April 2020 is the baseline for the time series because it represents the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in terms of unemployment rates and pairs with the time range of our second dependent variable. April creates a low point benchmark to measure which metros are recovering faster and who was impacted the least.

Three different outcome variables are drawn from the Opportunity Insights data to evaluate how the metros fared during the pandemic and how quickly they recovered.

-

1)

The first dependent variable is the seasonally adjusted credit/debit card spending compared to the baseline from January 2020. This variable measures the monthly average for each metro in comparison to the pre-pandemic baseline, January 2020 average. The range of this measure across the 50 largest US metros over 7 months varies from − 47 (47% below the January mean) to 23% (23% over the January mean).

-

2)

The second dependent variable is the percent change in small business net revenue seasonally adjusted and indexed to January 4–31, 2020. The range across metros is from − 76 to − 6%, indicating that in most months small businesses were losing a lot of revenue.

-

3)

The final outcome variable measures the percent change in the number of small businesses open, seasonally adjusted and indexed to January 4–31, 2020. The range of this measure is between − 58 and − 13%, again indicating that many small businesses were closed in these metro areas for many months. Figure 1 reports trends in credit card/debit card spending over the 9 months of our study, business revenue, and the percent of small businesses open or closed. These descriptive statistics alone paint a bleak picture of the economy in the USA in 2020, especially in the early months following the pandemic shock.

For a more complete understanding of the business climate in large metros, we supplement these commercial data with additional large sample survey data from the US Census (Fig. 2). The Small Business Pulse Survey (SBPS) was commissioned by the Census Bureau to track changes for small businesses nationally during the coronavirus pandemic. The survey began in April of 2020 and has continued through 2021. Individual responses are aggregated and available by sector for the states and the 50 most populous metros (see Appendix 1 for the listing of metros). The surveys were conducted weekly and to match the monthly data on the density of domain name hosts, the weekly values were aggregated to monthly means.Footnote 7

Two questions from the Small Business Pulse are used in the analysis to measure business owner perceptions.

The first asks: “Overall, how has this business been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic?” Respondents were given a 5-point scale from large negative effect, moderate negative effect, little or no effect, moderate positive effect, to large positive effect. The Census reported the percentage of respondents in each MSA who selected each category. Using the monthly means, the responses were then collapsed into 3 categories (overall negative, no change, and overall positive). Across all metros and time periods, the distribution of each of these categories is the following: overall negative (58 to 96%), no change (2 to 34%), and overall positive (0 to 14%). We model the probability that a negative change (or no change) is reported by business owners.

Our second dependent variable from the Small Business Pulse comes from a question about perceived revenue change. The question asks: “In the last week, did this business have a change in operating revenues/sales/receipts, not including any financial assistance or loans?”Footnote 8 Respondents were given the following options: (1) Yes, increased; (2) Yes, decreased, and (3) No change. Again, we used the weekly percentage responding to each category, aggregating the weekly percentages into monthly means for each MSA. Distributions for each category are decrease in revenue (22 to 85%), no change (9 to 69%), and revenue increase (0 to 25%). Similar to the responses on the overall effect, the distribution for change in revenues strongly favors a negative or no effect during the pandemic with few businesses reporting an increase in revenue. Accordingly, we focus on modeling decreased revenue effect and no effect in the following analysis.

On their own, each of these dependent variables provides only a partial insight into economic resilience during the heart of the Covid-19 pandemic. Together, however, they form a more complete picture of what the economic conditions in these communities looked like: from spending to small business activity to owner perceptions of the business environment.

6.3 Primary explanatory variable and controls

As discussed above, the primary explanatory variable is the density of digital businesses (domain name hosts) in the 50 largest metropolitan statistical areas. While the metros vary in population size, the range of this measure across communities is from approximately 1.5 domain name hosts per 100 people to a little over 10 per 100 people.

This study analyzes active domain name hosts (websites/SSL/email) and their redirects, representing over half of all US domain name hosts. This contrasts with domain name registration used in previous studies that can include inactive websites. Through a collaboration with GoDaddy, the researchers gained access to de-identified monthly customer data on these domain hosts in 2020. Monthly population data on the density of domain name hosts (websites per 100 people) in the USA provide a unique measure of digital economic activity within communities. Anonymized customer data with zip codes are aggregated to metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) for analysis, to be paired with monthly time series data from government and private sources. Data on the density of domain name hosts for metropolitan and micropolitan areas are publicly available dating back to May 2018 on the Venture Forward website.Footnote 9

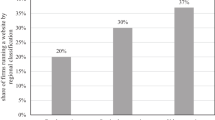

The domain name hosts have been further described in three online surveys with questions designed and analyzed by the authors and administered to random samples of over 2000 website owners in August 2019, July 2020, and July 2021 by the polling firm Advanis (https://www.advanis.net/).Footnote 10 According to the 2020 survey, most enterprises supported by domain name hosts are small or microbusinesses. More than half are operated by solo entrepreneurs; 38% have between 1 and 10 employees, and only 8% have more than 10. In 2020, the domain name hosts provided a main or supplemental source of income for 60% of their owners, again indicating their economic role. Nearly half served as the owner’s main source of employment, while 29% of customers reported their venture as secondary employment. Most commercial domain name hosts represent businesses with both a physical and online presence, 36% of respondents reported being online only in 2020. This contrasts with only 19% of ventures that were online-only in August 2019. This growth in online business activity is likely the result of pandemic-related social distancing measures. Owners also described their domain sites as resources for resilience. Among those surveyed in summer 2020, 61% said their website helped them navigate the pandemic.

Some other data are available to describe digital economic activity, such as Census data on e-commerce sales or Adobe’s Digital Economy Index. Census data on e-commerce is annual and covers only online sales,Footnote 11 missing other applications such as marketing and communications for brick-and-mortar businesses. Adobe’s high-frequency, global data is not available below the national level.Footnote 12 The Yelp Economic Average describes businesses advertised on its platform but omits online-only establishments.Footnote 13 The advantages of the domain name data are their granularity and reliability as a measure of broad digital economic activity, as well as their frequency. Table 1 summarizes data in 2020, covered here, to show trends over time.

The nation’s largest metros have more domain hosts per capita, as would be expected. Despite the economic downturn, the density of domain name sites increased during the economic and public health crisis.Footnote 14 Even as some businesses closed their doors, others added online services for brick-and-mortar establishments or launched businesses virtually. This was especially true in the largest metropolitan areas.

A number of variables are included in the statistical models to control for other factors that might affect local economies. As Sussan and Acs, (2017) argue, digital entrepreneurship is likely to be affected by broadband use in the population. We include a measure of broadband subscriptions. The relative prosperity of the community prior to the pandemic and labor force characteristics such as age and education (Liu, 2021; Moretti, 2012) may have influenced community resilience. As noted in previous research, metros with more educated populations were more resilient in recent recessions (Arias et al., 2016). Metropolitan areas with a higher proportion of residents of color may have more vulnerable businesses, given national trends for business owners of color during the pandemic (Fairlie, 2020; Perry et al., 2021). Controls for business sectors in the metropolitan area are included to account for community variation in the types of businesses that were most impacted (Parilla et al., 2020). The most recent 1-year estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau (2020) are used to measure broadband subscriptions (percent), demographic factors, and community variation across age groups, race/ethnicity, education, and business sectors.Footnote 15Footnote 16

The central research question is: Did a higher density of digital businesses in the metropolitan region help mitigate the shock of the crisis for small businesses? We expect communities with more digitally enabled commercial activity recovered more quickly compared to communities with less digitally active economies. The expectations can be formalized with the below equation:

where.

Yit is the specific economic measure of a metropolitan area

Yit-1 is the 1-month lag of the economic measure (only in some models)

Dit-1 is the 1-month lag of online domain density

Zit is a battery of metropolitan social and economic characteristics (controls).

Alpha is a vector of coefficients of the controls

εit is an error term

Each of these specific measures and expectations listed above provides a different view of economic conditions within the communities. For example, measures of small business revenue and openings directly address whether the business environment is improving or getting worse. Measures of credit card spending offer a more general gauge of economic conditions in the community, apart from whether small businesses are thriving. They therefore offer a point of comparison with small business outcomes during this period. While there are different measures of economic activity, we chose this measure because it is indexed to a pre-pandemic period (Jan 2020) and provides a granular time series that pairs well with our primary independent variable. Responses from the Small Business Pulse Survey report what business owners think about their own establishments and the surrounding environment. While each measure of resilience is useful on its own, we analyze them together to portray a more complete picture and to increase robustness.

7 Results

To examine whether a higher density of digitally enabled businesses in the metropolitan region helped to mitigate shocks for small businesses, we use multiple outcome measures. These include credit and debit card spending, small business revenues, and small business openings, as well as self-reported changes in revenues and perceived effects. Table 2 shows outcomes for the dependent variables from the Opportunity Insights data. Models 1 and 2 explore the effects of digital economic activity (domain/website density) on debit and credit card spending across the 50 largest US metros. Models 3 and 4 consider the impact of domain density on local business revenue. Finally, columns 5 and 6 model the role of this activity in small business openings. For each of these, the first model is our baseline model and the second model includes a lagged dependent variable (dynamic model). We include both specifications because both yield important insights. The first models consider the entire time frame for the effect. By controlling for the lagged dependent variable, the second models examine month over month change. This lagged panel design provides a stronger causal model, since so much of the variation in the outcome variable in MSA’s is explained by the prior month’s economic conditions. Inclusion of the lagged dependent variable can provide a stronger modeling strategy but runs the risk of overfitting the data since so much of the variation in the outcome variable is absorbed by the repeated observation for the same case in the prior month (there is a lively debate in the literature on lagged dependent variables — see Keele & Kelly, 2006; Wilkins, 2017). We report both modeling strategies below for transparency.

In model 1 (Table 2), the covariate for digital economic activity is positive and significant, indicating that an increase in the density of domain name sites is associated with higher debit/credit card spending across US metros over the months of the coronavirus pandemic shutdowns, all else equal. If we consider the coefficient in model 1, an increase in one website per 100 people leads to about a 2.1-point increase in average monthly credit card/debit card spending relative to January 2020, controlling for other factors. Varying the number of domains per 100 people from minimum to maximum values (about 9 points) increased credit card/debit card spending relative to January 2020 by about 19 points, or a 27% increase along the range of monthly credit/debit card spending compared to January 2020 (about 70 points). This is one indicator of a relatively stronger metropolitan economy during the pandemic, as this measures change compared to January 2020. Digital economic activity appears to have helped the metro economy overall.

Including the 1-month lag of the dependent variable also results in a significant finding for the domain density variable (see model 2). Thus, even over a short period, in month over month change, more digital commercial activity measured by the density of domain name websites had measurable beneficial effects on regional economies.

Models 3 and 4 of Table 2 predict business revenue, also providing strong results. Both models (with and without the lagged term) show a positive and statistically significant effect for digital economic activity. The coefficient from model 3 indicates that an increase in one website per 100 people leads to an approximately 2.7-point increase in average monthly business revenue relative to January 2020, controlling for other factors. Varying the number of domains per 100 people from minimum to maximum values (about 9 points) increased small business revenue relative to January 2020 by about 25 points (if we consider this across the entire range of revenue over this period, it amounts to about a 36% increase).

Model 4 replicates model 3 but with the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable for small business revenue. As expected, the coefficient for digital economic activity is substantially smaller, but still indicates about a 1.8-point increase in the percentage of small business revenue relative to January 2020 for every one-unit increase in domain name site density. Measuring month over month change, we still see a strong effect from digital businesses in the metro.

Finally, we turn to models 5 and 6, which explore the percentage of small business openings relative to January 2020. In some states, such as California, nearly half of businesses were closed for many months in Spring 2020. The results here are consistent with the other models. The coefficient for our primary explanatory variable in model 5 is roughly half that of the previous base models but still represents about a 1.3-point increase for small business openings for every increase in 1 domain name website per 100 people. Going from the minimum domain density to the maximum domain density leads to about a 12-point increase or about a 27 percent increase across the range of small business openings.

When controlling for the lagged dependent variable, which is then modeling month to month change in small business openings percentage, the coefficient for domain density is slightly larger at a 1.5-point increase for every domain name site per 100 people.

All in all, there is a consistent pattern across each of these models. Even when controlling for a wide variety of factors influencing the business and economic environment in communities, we still see positive and significant impacts from digital economic activity across US metros. Along with that, even when controlling for the previous month’s dependent variable, we see website density is strongly significant in all models. The simple conclusion that can be drawn from these models is that metropolitan areas with a stronger digital economy were more resilient in the pandemic.

Table 3 continues this exploration of how domain hosts are connected to business and economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, but this time we explore metropolitan fortunes in this period through the US Census Small Business Pulse Survey.

Table 3 considers the monthly mean responses within each metro for the overall effect the pandemic has had on small businesses along with revenue changes. The dependent variables are a “negative effect” (model 1) and “little to no change” (model 2), along with whether the business had a “negative change in revenues” in the last week (models 3) or if there was “no change in revenues” (model 4). Here we see evidence that even from a more subjective measurement (what business owners are saying), there is a link between digital economic activity and small business recovery. While the variable for “little to no effect” is not significant (model 2), the coefficient for a “negative effect” (model 1) is negative and significant. This indicates that an increase in digital economic activity leads to a decrease in the mean response that the pandemic has had an overall negative effect on the business. The coefficient of − 0.73 indicates that an increase in one domain per 100 people leads to about a 3/4-point decrease in average monthly responses that the pandemic has had a negative effect on businesses, controlling for other factors. Varying the number of domains per 100 people from minimum to maximum values (about 7 points for this sample) decreases the mean response by about 5 points, or about a 13% decrease along the range of mean responses that the pandemic has had a negative effect.

As for reported revenue (models 3 and 4), there is a similar pattern. Metros with more digital economic activity are negative and significant for decreased revenues and positive and significant for no change in revenues. For decreased revenues, varying the domain density from the minimum to maximum values leads to a reduction in the mean response of decreased revenues by about 12.6 points (or about 20% across the range of the dependent variable). Similarly, for no revenue change, going from minimum to maximum values leads to about a 14-point increase in the likelihood that local businesses perceived no change (or about 23% across the dependent variable range). This complements the results from the Opportunity Insights models (Table 2) in that domain host density is linked to more positive economic conditions and perceptions.

Taken as a whole, the results all point in the same direction, showing that the presence of more digital economic activity proxied by domain name sites had a positive effect on metropolitan resilience for small businesses during 2020 disruptions. We see this in the presence of objective measures from Opportunity Insights data and from more subjective measures from the US Census Small Business Pulse. Overall, most communities faced economic hardships, but our results show that areas with a robust online business climate did better on average than those communities without it.

Summary of results | ||

|---|---|---|

Communities with higher digital economic activity should: | Overall (entire time frame) | Month over month |

Have higher levels of credit/debit card spending | \(\surd\) | \(\surd\) |

Have higher levels of small business revenue | \(\surd\) | \(\surd\) |

Have more small business openings | \(\surd\) | \(\surd\) |

Have a lower level of small businesses reporting revenue decreases | \(\surd\) | na |

Have a higher level of small businesses reporting little to no change in revenue | \(\surd\) | na |

Have a lower level of small businesses reporting a negative effect | \(\surd\) | na |

Have a higher level of small businesses reporting little to no effect | na | |

8 Conclusion: digital resilience for small businesses in metros

Small businesses suffered disproportionately during the sudden and unprecedented disruptions of 2020. There is a need to explore the extent to which digital technologies helped these entrepreneurs and their communities to absorb these shocks and adapt. Domain name hosts, and the websites they support, are commonly used by even the smallest of establishments, including sole proprietorships, and they provided a platform for online communications and transactions during Covid-19.

Metro-level data on the density of domain name hosts offer a view of how digital activity matters for the resilience of small businesses in communities, beyond outcomes for individual firms. Across multiple indicators, higher digital activity in metropolitan areas is linked to more positive economic outcomes and perceptions for small businesses during the pandemic. These results are found across MSAs and over time (using monthly time series data). The multivariate regression time series models are used to develop causal explanations, even lagging the outcome variable to measure month over month change. From the Opportunity Insights data, we noted a connection between domain host density and increasing ratios of credit and debit card spending, along with small business revenue and small business openings compared to a pre-pandemic baseline of January of 2020. Spending provided a more general indicator of the health of the local economy, while revenue and openings addressed resilience for small establishments within them.

Similarly, the Small Business Pulse data demonstrated that metros with higher digital economic activity were less likely to have small business owners who perceived a negative effect during the pandemic, including reported decreases in revenues. These results describe developments in the metropolitan regions that dominate the national economy.

As Chetty et al., (2020) have argued, commercial data is a resource for tracking the recovery going forward, as well as developments in local economies more generally. Advances in computation and data analytics have made possible the introduction of data mined from many new sources, including anonymized commercial data shared for research and policy deliberation (King, 2016). The scale and scope of such data can offer new insights through its granularity and frequency, especially for addressing emerging or rapidly changing societal problems (Bright & Margetts, 2016; Cook, 2014; Glaeser et al., 2019). Our analysis demonstrated the value of considering new measures of digital economic activity to understand how businesses and communities weathered a fast-moving crisis. With month-to-month data and time series analysis, we are able explore trends in real time. There can also be some limitations for commercial data, as with other types of secondary data. The domain name hosts include a minority of non-business websites, for example, though robustness checks using commercial-only domain sites obtained through web crawling produced similar results. In this case and in prior studies, the density of these sites in the aggregate has been a significant predictor of economic outcomes in communities (Mossberger et al., 2021; Yu & Bengali, 2021), and we expect that it will be useful for future research. While this analysis leveraged high-frequency outcomes that were available only for the largest metros to address changing conditions in the pandemic, the domain site data are available for all counties, metropolitan and micropolitan areas. Exploring outcomes in the longer term will be possible with annual census data and other measures to examine how digital activity impacts economic resilience in all communities.

Beyond the pandemic is the question of what lies ahead for recovery. Domain name hosts experienced even faster growth than the general surge in business startups during 2020 (O’Donnell et al., 2021), with a 60% increase in new domain sites compared to a 24% rise in business registrations. This could support greater innovation for small businesses in an increasingly digital economy. In the face of disruptions that included job loss, changing career attitudes, and a rise in remote work (Howe et al., 2021; Zagorsky, 2022), websites may also reduce the costs for fledgling entrepreneurs who decide this is an opportune time to start a business. For existing businesses as well, new digital economic activity may expand markets for firms that have been locally based. Further research will be needed to understand the role this plays in communities in the longer term, in the volatile recovery that has followed.

Given forecasts for continued expansion of technology use in entrepreneurship (Belitski et al., 2021), digital skills and tools will become increasingly important for small business development programs. New federal funding for broadband infrastructure and digital inclusion programs will likely increase the need for digital activity on the part of small businesses, as well as opportunities for state and local governments to address this need. Local economic development strategies often focus on attracting technology firms when considering the digital transformation of the economy; but addressing the digital needs of small business may be one path toward a more inclusive and equitable recovery for communities.

Notes

A venture is the term used by GoDaddy to describe unique domain name hosts and their redirects to a single domain name (website/email/ssl). Metrics from Data Provider (Netherlands) indicate there are roughly 40 million ventures in the USA.

Fairlie found a 25% decline in business activity among women-owned businesses between February and April 2020, compared to a 20% decline among male-owned businesses.

Similar results were found using other cross-sectional time series panel regression models. Given the use of time variant and invariant variables, fixed effects models were inappropriate.

Opportunity Insights. https://opportunityinsights.org/

We collapsed the following survey weeks into the following months: April (week 1), May (weeks 2–5), June (weeks 6–9), July (no surveys conducted), August (weeks 10–12), September (weeks 13–16), October (weeks 17–18), November (weeks 19–21), December (weeks 22–25). See https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/small-business-pulse-survey.html for full information about the Small Business Pulse Survey. Different waves of the SBPS were not continuous so there were some gaps within the analysis. Specifically, the survey began near the end of April, no surveys were conducted in July, and there were some weekly gaps between the various waves of the survey.

Question wording changed slightly between waves but overall, they were nearly identical. The question wording supplied above was from waves 2 and 3. For the first few weeks of wave 1, the question wording read: “In the last week, did this business have a change in operating revenues?” For the second half of the first wave, it asked: “In the last week, did this business experience a change in operating revenues/sales/receipts, not including any financial assistance or loans?”.

GoDaddy Venture Forward. https://www.godaddy.com/ventureforward/reports-and-resources/

The surveys were conducted online, with respondents contacted with an email invitation. In August 2019, there were 2006 respondents, and in July 2020, 2330 complete using similar methods. Participants were given a $10 Amazon gift card as an incentive. Respondents were restricted to website owners or employees responsible for the site, and contractors were excluded in an initial screening question.

2018 E-commerce Multi-sector Data Tables (https://www.census.gov).

This stability continues into the latest month for which we have data, November 2020. Venture density correlates at more than .95 across all time periods, including from November 2018 to November 2020.

We omit median income from our models due to high collinearity and correlation with a variety of our controls; such as educational attainment. When replacing these measures with median income, we attain similar results.

References

Ananthakrishnan, U. M., Chen, J., & Susarla, A. (2020). No pain, no gain: Examining the digital resilience of the fitness sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3740143

Andersson, M., & Larsson, J. P. (2016). Local entrepreneurship clusters in cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu049

Arias, M. A., Gascon, C. S., & Rapach, D. E. (2016). Metro business cycles. Journal of Urban Economics, 94(C), 90–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2016.05.005

Bartik, A. W., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E. L., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business outcomes and expectations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(30), 17656–17666. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2006991117

Beck, N., & Katz, J. N. (1996). Nuisance vs. substance: Specifying and estimating time-series-cross-section models. Political Analysis: An Annual Publication of the Methodology Section of the American Political Science Association, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/6.1.1

Belitski, M., Guenther, C., Kritikos, A. S., & Thurik, R. (2021). Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00544-y

Box-Steffensmeier, J.M., Freeman, J.R., Hitt, M.P., & Pevehouse, J.C.W. 2014. Time Series Analysis for the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press.

Bright, J., & Margetts, H. (2016). Big data and public policy: Can it succeed where E-participation has failed? Policy & Internet, 8:218-224. Retrieved fromhttps://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.130

Cardflight (2020). Cardflight Small Business Report. Retrieved from https://www.cardflight.com/small-business-impact

OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities. (2020). Coronavirus (COVID-19): SME policy responses. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/coronavirus-covid-19-sme-policy-responses-04440101/

Chetty, R., Friedman, J. N., Hendren, N., Stepner, M., & The Opportunity Insights Team. (2020). The economic impacts of COVID-19: Evidence from a new public database built using private sector data (NBER Working Paper No. 27431). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27431

Cook, T. D. (2014). Big data in research on social policy. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(2), 544–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21751

Dörr, J. O., Kinne, J., Lenz, D., Licht, G., & Winker, P. (2021). An integrated data framework for policy guidance in times of dynamic economic shocks (Discussion Paper No. 21–062). Centre for European Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3924887

Digitally Driven. (2020). U.S. small businesses find a digital safety net during Covid-19. Connected Commerce. https://digitallydriven.connectedcouncil.org/

Digitally Driven (2021). European small businesses find a digital safety net during Covid-19. Report. Connected Commerce. Available at: https://digitallydriven.connectedcouncil.org/europe/

Ettlinger, M. And Hensley, J. (2021). COVID-19 economic crisis: By state. University of New Hampshire: Carsey School of Public Policy. Retrieved from https://carsey.unh.edu/COVID-19-Economic-Impact-By-State

Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first 3 months after widespread social-distancing restrictions. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy. https://doi.org/10.1111/jems.12400

Fazio, C.E., Guzman, J., Liu, Y., & Stern, S. (2021). How is COVID changing the geography of entrepreneurship? Evidence from the Startup Cartography Project (NBER Working Paper No. 28787). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28787

Glaeser, E. L., Kim, H., & Luca, M. (2019). Nowcasting the local economy: Using Yelp data to measure economic activity (NBER Working Paper No. 24010). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w24010

Greenstein, S., Goldfarb, A., & Forman, C. (2018). How geography shapes—and is shaped by—the internet. In G. Clark, M. Feldman, M. Gertler, & D. Wojcik (Eds.), The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography (pp. 269–285). Oxford University Press.

Howe, D. C., Chauhan, R. S., Soderberg, A. T., & Buckley, M. R. (2021). Paradigm shifts caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizational Dynamics, 50(4), 100804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2020.100804

ICANN. (2012). Internet corporation for assigned names and numbers. https://www.icann.org/resources/pages/welcome-2012-02-25-en

Keele, L., & Kelly, N. J. (2006). Dynamic models for dynamic theories: The ins and outs of lagged dependent variables. Political Analysis, 14(2), 186–205. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpj006

Kim, J. & Loh, T.H. (2021). What the recovery from the Great Recession reveals about post-pandemic work and cities. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/03/02/what-the-recovery-from-the-great-recession-reveals-about-post-pandemic-work-and-cities/

King, G. (2016). Preface: Big data is not about the data! In R. Michael Alvarez (Ed.), Computational Social Science: Discovery and Prediction. Cambridge University Press.

Koetsier, J. (2020). COVID-19 accelerated e-commerce growth 4 To 6 Years. Forbes Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnkoetsier/2020/06/12/covid-19-accelerated-e-commerce-growth-4-to-6-years/?Sh=5acae20f600f

Kolko, J. (1999). The death of cities? The death of distance? Evidence from the geography of commercial Internet usage. Cities in the Global Information Society Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Kost, D. (2020). How to help small businesses survive COVID’s next phase. Harvard Business School. Retrieved from https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/how-to-help-small-businesses-survive-covid-s-next-phase

Kramer Mills, C., & Battisto, J. (2020). Double jeopardy: Covid-19’s concentrated health and wealth effects in Black communities. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Retrieved from https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/smallbusiness/doublejeopardy_COVID19andBlackOwnedBusinesses

Liu, A. 2021. The right way to rebuild cities for post-pandemic work. Bloomberg News. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-04-09/the-right-way-to-rethink-cities-for-post-covid-work

Loh, T., Goger, A., & Liu, S. (2020). Back to work in the flames: The hospitality sector in a pandemic. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/08/20/back-to-work-in-the-flames-the-hospitality-sector-in-a-pandemic/.

Long, H. (2021). The economy isn’t going back to February 2020. Fundamental shifts have occurred. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/06/20/us-economy-changes/

Magis, K. (2010). Community resilience: An indicator of social sustainability. Society & Natural Resources, 23(5), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920903305674

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 38(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620949136

Matarrita-Cascante, D., Trejos, B., Qin, H., Joo, D., & Debner, S. (2017). Conceptualizing community resilience: Revisiting conceptual distinctions. Community Development, 48(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2016.1248458

Moretti, E. (2012). The New Geography of Jobs. First Mariner Books.

Moss, M. L., & Townsend, A. (1997). Tracking the net: Using domain names to measure the growth of the internet in U.S. cities. Journal of Urban Technology, 4(3):47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10630739708724566

Mossberger, K., Lacombe, S., & Tolbert, C. J. (2021). A new measure of digital economic activity and its impact on local opportunity. Telecommunications Policy, 102231.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2021.102231

Muro, M., Maxim, R., & Whiton, J. (2020). The places a COVID-19 recession will likely hit hardest. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2020/03/17/the-places-a-covid-19-recession-will-likely-hit-hardest/

Muro, M., You, Y., Maxim, R., & Niles, M. (2021). Remote work won’t save the heartland. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/06/24/remote-work-wont-save-the-heartland/

Norris, F. H., Stevens, S. P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K. F., & Pfefferbaum, R. L. (2008). Community resilience as a metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for disaster readiness. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(1–2), 127–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

Noy, I., & Yonson, R. (2018). Economic vulnerability and resilience to natural hazards: A survey of concepts and measurements. Sustainability: Science Practice and Policy, 10(8), 1–16. https://econpapers.repec.org/repec:gam:jsusta:v:10:y:2018:i:8:p:2850-:d:163169

O’Donnell, J., Newman, D., & Fikri, K. (2021). The startup surge? Unpacking 2020 trends in business formation. Economic Innovation Group. Retrieved from https://eig.org/news/the-startup-surge-business-formation-trends-in-2020

Parilla, J., Liu, S., & Whitehead, B. (2020). How local leaders can stave off a small business collapse from COVID-19. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/how-local-leaders-can-stave-off-a-small-business-collapse-from-covid-19/

Perry, A. M., Boyea-Robinson, T., & Romer, C. (2021). How Black-owned businesses can make the most out of the Biden infrastructure plan. Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2021/04/29/how-black-owned-businesses-can-make-the-most-out-of-the-biden-infrastructure-plan/

Pierri, N., & Timmer, Y. (2020). IT shields: Technology adoption and economic resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic (Working Paper No. 20/208). International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/09/25/IT-Shields-Technology-Adoption-and-Economic-Resilience-during-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-49754

Pozhidaev, D. (2021). Conceptualizing urban economic resilience at the time of Covid-19 and beyond. Journal of Applied Business and Economics, 23(3). https://doi.org/10.33423/jabe.v23i3.4349

Priyono, A., Moin, A., & Putri, V. N. A. O. (2020). Identifying digital transformation paths in the business model of SMEs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 6(4), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040104

Raj, M., Sundararajan, A., & You, C. (2020). COVID-19 and digital resilience: Evidence from Uber Eats. NYU Stern School of Business. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3625638

Safegraph. (2021). U.S. Consumer activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https:/www.safegraph.com/data-examples/covid19-commerce-patterns

Sussan, F., & Acs, Z. J. (2017). The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9867-5

Ungerer, C., & Portugal, A. (2020). Leveraging e-commerce in the fight against COVID-19. The Brookings Institution. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2020/04/27/leveraging-e-commerce-in-the-fight-against-covid-19/

United States Census Bureau. (2020). Small Business Pulse Survey: Tracking changes during the coronavirus pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/experimental-data-products/small-business-pulse-survey.html

U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). 2019 American community survey 1-year public use microdata samples. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/

Wilkins, A. (2017). To lag or not to lag?: Re-evaluating the use of lagged dependent variables in regression analysis. Political Science Research and Methods, 6(2), 393–411. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2017.4

Wilson, G. A. (2012). Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision-making. Geoforum, 43, 1218–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.03.008

Yelp. (2020). Local economic impact report: September 2020. Retrieved from https://www.yelpeconomicaverage.com/business-closures-update-sep-2020.html

Yu, W., & Bengali, L. (2021). Digital infrastructure, the economy and online microbusinesses: Evidence from GoDaddy’s microbusiness data. UCLA Anderson Forecast. https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/document/2021-07/uclaforecast_June2021_Yu-Bengali.pdf

Zagorsky, J.L. (2022). The great resignation: Historical data and a deeper analysis shows it’s not as great as screaming headlines suggest. Route Fifty, January 11, 2022. https://www.route-fifty.com/management/2022/01/great-resignation-historical-data-anddeeper-analysis-show-its-not-great-screaming-headlines-suggest/360611/

Zook, M. A. (2000). The web of production: The economic geography of commercial Internet content production in the United States. Environment & Planning A, 32(3), 411–426. https://doi.org/10.1068/a32124

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mossberger, K., Martini, N.F., McCullough, M. et al. Digital economic activity and resilience for metros and small businesses during Covid-19. Small Bus Econ 60, 1699–1717 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00674-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00674-x