Abstract

Cooper pairs in non-centrosymmetric superconductors can acquire finite centre-of-mass momentum in the presence of an external magnetic field. Recent theory predicts that such finite-momentum pairing can lead to an asymmetric critical current, where a dissipationless supercurrent can flow along one direction but not in the opposite one. Here we report the discovery of a giant Josephson diode effect in Josephson junctions formed from a type-II Dirac semimetal, NiTe2. A distinguishing feature is that the asymmetry in the critical current depends sensitively on the magnitude and direction of an applied magnetic field and achieves its maximum value when the magnetic field is perpendicular to the current and is of the order of just 10 mT. Moreover, the asymmetry changes sign several times with an increasing field. These characteristic features are accounted for by a model based on finite-momentum Cooper pairing that largely originates from the Zeeman shift of spin-helical topological surface states. The finite pairing momentum is further established, and its value determined, from the evolution of the interference pattern under an in-plane magnetic field. The observed giant magnitude of the asymmetry in critical current and the clear exposition of its underlying mechanism paves the way to build novel superconducting computing devices using the Josephson diode effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Semiconductor junctions, which exhibit direction-dependent non-reciprocal responses, are essential to modern-day electronics1,2,3. On the other hand, a key component of many quantum technologies is the superconducting Josephson junction (JJ) where two superconductors are coupled via a weak link4. JJs can be used for the quantum sensing of small magnetic fields5,6, single-photon detection7,8,9 and quantum computation10,11,12. Despite the longstanding research on superconductivity, the realization of the superconducting analogue of the diode effect, that is, the dissipationless flow of supercurrent along one direction but not the other, has been reported only recently in superconducting thin films13 and JJs14,15. However, a clear experimental evidence for a specific mechanism leading to this effect is lacking. Recent theoretical work16,17,18 has proposed that in two-dimensional (2D) superconductors with strong spin–orbit coupling under an in-plane magnetic field, Cooper pairs can acquire a finite momentum and give rise to a diode effect, where the direction of the Cooper pair momentum determines the polarity of the effect. At the same time, although there exist prior theoretical proposals19,20,21,22, none of them have been experimentally realized, and a theoretical description for a field-induced diode effect in JJs (the Josephson diode effect (JDE)) that would match experimental observations has not yet been formulated.

In this work, we report the discovery of a giant JDE in a JJ in which a type-II Dirac semimetal NiTe2 couples two superconducting electrodes and provide clear evidence of its interrelation with the presence of finite-momentum Cooper pairing. The effect depends sensitively on the presence of a small in-plane magnetic field. Non-reciprocity ΔIc—the difference between the critical currents for opposite current directions—is antisymmetric under an applied in-plane magnetic field Bip. Further, ΔIc strongly depends on the angle between Bip and the current direction and is the largest when Bip is perpendicular to the current and vanishes when Bip is parallel to it. Moreover, we also observe multiple sign reversals in ΔIc when the magnitude of Bip is varied. Our phenomenological theory shows that the presence of a finite Cooper pair momentum (FCPM) and a non-sinusoidal current–phase relation account for all the salient features of the observed JDE, including the angular, temperature and magnetic-field dependences of the observed ΔIc. The distinct evolution of the interference pattern under the in-plane magnetic field further establishes the presence of FCPM in this system. We examine the plausibility of the FCPM resulting from the momentum shift of the topological surface states of NiTe2 under an in-plane magnetic field, by performing angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy (ARPES) measurements and comparison with density functional theory (DFT) calculations. This paper presents the temperature, field and angle dependences of the JDE, and is the only work to date, to the best of our knowledge, in which the fundamental properties of the effect can be explained within a single model providing clear evidence that the features are consistent with FCPM in the presence of a magnetic field.

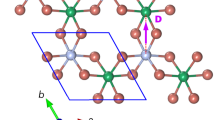

NiTe2 crystallizes in a CdI2-type trigonal crystal structure with the space group P\({\bar 3}\)m1, which is centrosymmetric23,24 (Supplementary Section I). This 2D van der Waals material is a type-II Dirac semimetal that hosts several spin-helical topological surface states23,24. As discussed later, these surface states play a key role in the JDE. JJ devices were fabricated on NiTe2 flakes that were first mechanically exfoliated from a single crystal (Methods). Figure 1a shows the optical images of several JJ devices formed on a single NiTe2 flake, where the edge-to-edge separation (d) between the superconducting contacts (formed from 2 nm Ti/30 nm Nb/20 nm Au) in each device is different. A schematic of the JJ device is shown in the absence (Fig. 1b) and presence (Fig. 1c) of a Josephson current, where x is parallel to the current direction and z is the out-of-plane direction. The temperature dependence of the resistance of the device with d = 350 nm (Fig. 1d) shows two transitions: the first transition (TSC) at T ≈ 5.3 K is related to the superconducting electrodes25. A second transition (TJ) takes place at a lower temperature when the device enters the Josephson transport regime such that a supercurrent flows through the NiTe2 layer. The dependence of both TSC and TJ as a function of the edge-to-edge separation d between the electrodes is shown in Fig. 1d, inset. Although TSC is independent of d, TJ decreases with increasing d, which corroborates that TJ corresponds to the superconducting proximity transition of the JJ device26.

a, Optical microscopy image of several JJ devices formed on a single NiTe2 exfoliated flake. Evidently, the edge-to-edge spacing d between the superconducting electrodes varies for each device. b, Schematic of the Josephson device. c, When the Josephson current flows through the junction (I+ corresponds to the Josephson current flowing in the +x direction), the critical current is different depending on its direction. d, Voltage as a function of temperature at zero field for a JJ device with d = 350 nm that shows two transitions at TSC and TJ. The inset shows the variations in TSC and TJ with d. e, I–V curve of a JJ device with d = 350 nm at 20 mK and an in-plane magnetic field By = 20 mT showing large non-reciprocal critical current, namely, Ic– and Ic+. f, Rectification effect observed using currents between |Ic–| and Ic+ for the same JJ device at 20 mK and By = 20 mT.

To observe the JDE (Fig. 1b,c), we carried out current versus voltage (I–V) measurements as a function of temperature and magnetic field. Figure 1e shows I–V curves in the presence of an in-plane magnetic field By ≈ 20 mT perpendicular to the direction of the current for the device with d = 350 nm. The device exhibits four different values of critical current with a large hysteresis, indicating that the JJs are in the underdamped regime27. During the negative-to-positive current sweep (from −50 to +50 µA), the device shows two critical currents, namely, Ir– and Ic+, whereas during a positive-to-negative current sweep (from +50 to −50 µA), the device exhibits two other critical currents, namely, Ir+ and Ic–. In the rest of the paper, we concern ourselves with the behaviour of the critical currents Ic– and Ic+, which correspond to the critical values of the supercurrent when the system is still superconducting. For small magnetic fields, we find that the absolute magnitude of Ic– is clearly much larger than that of Ic+ (Fig. 1e) (Supplementary Section II details the zero-field data where Ic+ = |Ic–|). These different values of Ic+ and |Ic–| mean that when the absolute value of the applied current lies between Ic+ and |Ic–|, the system behaves as a superconductor for the current along one direction whereas a normal dissipative metal for the current along the opposite direction. We use this difference to demonstrate a clear rectification effect (Fig. 1f) that occurs for currents larger than Ic+ but smaller than |Ic–|.

To probe the origin of the JDE, the evolution of ΔIc (ΔIc ≡ Ic+ – |Ic–|) was examined as a function of the applied in-plane magnetic field at various temperatures and angles with respect to the current direction. The dependence of ΔIc on By (field parallel to the y axis and perpendicular to the current) at different temperatures demonstrates that ΔIc is antisymmetric with respect to By (Fig. 2a). At 60 mK, ΔIc exhibits the maximum and minimum values at By = ∓12 mT, respectively (Fig. 2a), and the ratio \(\frac{{{{\Delta }}I_{\mathrm{c}}}}{{ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > }}\) is as large as 60%, where \({ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > } = \frac{{\left( {I_{{\mathrm{c}} + } + \left| {I_{{\mathrm{c}} - }} \right|} \right)}}{2}\). We find that the magnitude of \(\frac{{{{\Delta }}I_{\mathrm{c}}}}{{ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > }}\) systematically increases as the distance (d) between the superconducting electrodes is decreased: for the device with d = 120 nm, \(\frac{{{{\Delta }}I_{\mathrm{c}}}}{{ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > }}\) is as large as 80% (Supplementary Section III). Such a large magnitude of \(\frac{{{{\Delta }}I_{\mathrm{c}}}}{{ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > }}\) at a low magnetic field (By ≈ 12 mT) makes this system unique, compared with previous reports where either the magnitude of \(\frac{{{{\Delta }}I_{\mathrm{c}}}}{{ < I_{\mathrm{c}} > }}\) was found to be small or a large magnetic field was required to observe a substantial effect13,14,15. We also observe multiple sign reversals in ΔIc when Bip is increased (Supplementary Section IV), a previously unobserved but interesting dependence that is critical to unravelling the origin of the JDE, as discussed below.

a, Variation in ΔIc as a function of By at selected temperatures in a JJ device with d = 350 nm. b,c, Dependence of ΔIc as a function of in-plane magnetic field applied at different angles with respect to the current direction (b) and the corresponding colour contour map for the same device (c). Here θ = 0°/±180° (±90°) correspond to the in-plane magnetic field when it is perpendicular (parallel) to the current direction. d, Dependence of ΔIc on temperature for By = 12 mT for the same device. The inset shows a quadratic dependence (T – TJ)2 of ΔIc on temperature close to TJ. e,f, Calculation of the dependence of ΔIc on the angle of the in-plane magnetic field (e) and the corresponding colour map (f), obtained using equation (7) for Bd = 22 mT and Bc = 45 mT.

The dependence of ΔIc on the direction of the in-plane magnetic field with respect to the current is shown for several field strengths (Fig. 2b,c). At smaller fields, |ΔIc| is the largest when the field is perpendicular to the current (θ = 0°/±180°, where θ is the in-plane angle measured with respect to the y axis) and vanishes when the field and current are parallel (θ = ±90°). With regard to the temperature dependence of ΔIc, we find that the magnitude of ΔIc increases monotonically as the temperature is lowered (Fig. 2a). For a quantitative understanding, the temperature dependence of ΔIc for By = 12 mT (the field at which ΔIc takes the largest value) is shown in Fig. 2d. At temperatures near TJ, the variation in ΔIc with temperature can be well fitted by the equation ΔIc = α(T – TJ)2, where α is a fitting parameter (Fig. 2d, inset).

We propose a possible origin of the JDE as follows. At temperatures close to TJ at which superconducting correlations develop in the proximitized region26,28,29 and the Josephson effect emerges (Fig. 1d), the free energy F of our system can be expanded in powers of the superconducting order parameters of the two superconducting electrodes, namely, Δ1,2, in the proximitized regions:

where F0 is the free energy in the absence of Josephson coupling, and γ1 and γ2 denote, respectively, the first- and second-order Cooper pair tunnelling processes across the weak link. The presence of higher harmonics account for a non-sinusoidal current–phase relation, as commonly observed in superconductor-normal metal–superconductor junctions with high transmission. Importantly, in the absence of time-reversal and inversion symmetries, γ1,2 are complex numbers, which makes the critical current non-reciprocal, as shown below.

Expressing the order parameters Δ1,2 in terms of their amplitude and phase as \({{\varDelta }}_{1,2} = {{\varDelta }}{\mathrm{e}}^{{\mathrm{i}}\varphi _{1,2}}\), the free energy takes the form F = F0 – 2|γ1|Δ2cosφ – |γ2|Δ4cos(2φ + δ), where φ = φ2 – φ1 + arg(γ1) is effectively the phase difference between the two superconducting regions. Note that, indeed, when both time-reversal and inversion symmetries are broken, the phase-shifted JJ is realized, as observed elsewhere30. Here δ = arg(γ2) – 2arg(γ1) is the phase shift associated with the interference between the first-order (γ1) and second-order (γ2) Cooper pair tunnelling processes. The Josephson current–phase relation then includes the second harmonic as

where \({{\varPhi }}_0 = \frac{h}{{2{{e}}}}\) is the superconducting flux quantum, h is Planck’s constant and ℏ = h/2π. When Δ4|γ2| is small, the critical current of the JJ is reached near a phase difference of φ ≈ ±π/2 and equals

The non-reciprocal part of the critical current is proportional to Δ4.

Since the pairing potential in the proximitized layer behaves as \({{\varDelta }} \propto \sqrt {1 - \frac{T}{{T_{\mathrm{J}}}}}\) (refs. 26,28,29), the temperature dependence of ΔIc near TJ is then given by

which explains our experimentally measured temperature dependence of ΔIc (Fig. 2d, inset).

Another feature is that ΔIc can change sign as the applied field increases (for example, near Bip ≈ 22 mT (Fig. 2a,c)). Such a sign reversal in ΔIc can be reproduced by including the field dependence of the order parameters \({{\varDelta }}_{1,2} \propto \sqrt {1 - \left( {\frac{{\left| {{{\bf{B}}}} \right|}}{{B_{\mathrm{c}}}}} \right)^2}\) (where Bc is the critical field in the proximitized region) and of the phase shift δ due to the Cooper pair momentum.

The in-plane magnetic field Bip can induce an FCPM in the junction. We discuss the possible origins of the finite-momentum pairing: the screening current31 and/or the Zeeman effect on topological surface states32,33,34. We discuss both these possible origins in detail later in the text, but note that they have the same symmetry. We also note that the phenomenological theory presented here applies to a wider class of JJs made with strongly spin–orbit-coupled materials, where the Zeeman effect can lead to FCPM33.

In the presence of momentum shift qx under By, the proximitized region effectively turns into a finite-momentum superconductor. The presence of Cooper pair momentum results in a phase shift accumulated during the Cooper pair propagation across the junction: δ ≈ 2qxd. At small values of the field, qx must be linear in By such that

where Bd is a property of the junction geometry and material that can, in principle, be determined based on the specific microscopic origin of the field-induced Cooper pair momentum. As a result, ΔIc will have the following field dependence:

Depending on the ratio \(\frac{{B_d}}{{B_{\mathrm{c}}}}\), different scenarios can be realized from this equation; for \(\frac{1}{{2(n + 1)}} < \frac{{B_d}}{{B_{\mathrm{c}}}} < \frac{1}{n}\), there are n sign reversals in ΔIc when the magnetic field is applied in the y direction.

Figure 2e,f shows the dependences of ΔIc on the magnitude of By and the direction of the in-plane magnetic field as obtained from our phenomenological model (equation (7)), where we used Bc = 45 mT and Bd ≈ 22 mT (Supplementary Section V). To explain the angular direction dependence, we take into account that the non-reciprocal part of the current is proportional only to the x component of momentum shift qx that is proportional to the By = Bipcosθ component of the in-plane magnetic field. In Fig. 2f, it is evident that in each domain \(- \frac{\uppi }{2} + \uppi n < \theta < \frac{\uppi }{2} + \uppi n\), the sign reversal of ΔIc occurs where the condition \(\sin \left( {\uppi \frac{{B_{{\mathrm{ip}}}\cos \;\theta }}{{B_d}}} \right) = 0\) is fulfilled, which is evident in Fig. 2c. Thus, our model successfully captures the main features of the JDE, as seen in our experimental data.

To confirm the emergence of a FCPM under an in-plane magnetic field, we examine the evolution of the interference pattern (\(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}V}}{{{\mathrm{d}}I}}\) versus Bz) with the field Bx parallel to the current direction (Fig. 3b). This interference pattern has a similar resemblance with the Fraunhofer pattern such that a higher Ic in the latter translates to a lower \(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}V}}{{{\mathrm{d}}I}}\) in the former33,34. For this in-plane field orientation (Bx), the Cooper pairs acquire finite momentum 2qy along the y direction (Fig. 3a), which should not generate a JDE but is expected to change the interference pattern. When a Cooper pair tunnels from position (x = 0, y1) in the left superconductor with order parameter \({{\varDelta }}_1\left( {y_1} \right) = {{\varDelta }}{\mathrm{e}}^{2{\mathrm{i}}q_yy_1}\) to the superconductor on the right at (x = deff, y2) with \({{\varDelta }}_2\left( {y_2} \right) = {{\varDelta }}{\mathrm{e}}^{2{\mathrm{i}}q_yy_2 + {\mathrm{i}}\varphi _0}\) (where deff = d + 2λ is the effective length of the junction and λ = 140 nm is the London penetration depth in Nb (ref. 35)), the contribution of this trajectory to the current involves a phase factor proportional to the Cooper pair momentum33,34:

in addition to the usual phase factor \(\frac{{2\uppi B_zd_{{\mathrm{eff}}}\left( {y_1 + y_2} \right)}}{{{{\varPhi }}_0}}\) due to the magnetic flux associated with Bz. The interference pattern is a result of interference from all such trajectories (Fig. 3b,c).

a, Schematic of the JJ in the presence of an in-plane magnetic field parallel to the current direction, leading to the emergence of an FCPM in the y direction. The waves illustrate the oscillations of the real part of the order parameter in the vicinity of the leads that occur due to the finite-momentum pairing. b, Dependence of \(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}V}}{{{\mathrm{d}}I}}\) on in-plane (Bx) and out-of-plane (Bz) magnetic field for a JJ device with d = 350 nm, showing the evolution of the interference pattern due to the applied in-plane magnetic field. The colour corresponding to the normalized magnitude of \(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}V}}{{{\mathrm{d}}I}}\) is shown on the right side of each figure. The red diamonds correspond to the positions of the centres of the peaks with respect to Bx and the solid lines correspond to the linear fits used to determine the slopes of the side branches (Supplementary Section VI). c, Calculation of the evolution of the interference pattern expressed as a function of Bz, where the colour represents the value of Ic. The solid lines mark the side branches with the slope corresponding to the average of the experimentally obtained slopes \(\left( {\frac{{{{\Delta }}B_x}}{{{{\Delta }}B_z}}} \right)_{{\mathrm{avg}}}\) ≈ 13. We note that the qualitative behaviour of \(\frac{{{\mathrm{d}}V}}{{{\mathrm{d}}I}}\) is the same as that of Ic, including periodicity with respect to Bz and slope of the side branches34.

Due to the additional phase Δφ from the in-plane-field-induced Cooper pair momentum, the interference pattern evolves as the in-plane field is increased, splitting into two branches. The Cooper pair momentum 2qy can be extracted from the slope of the side branches33,34 (Fig. 3b, solid lines). For the d = 350 nm device, we estimate the average slope to be \(\frac{{B_x}}{{B_z}}\) ≈ 13 (Supplementary Section VI details the estimation process). In Fig. 3c, we show the calculated critical Josephson current, obtained by summing over quasi-classical trajectories (Supplementary Sections VII and VIII), which has a qualitatively similar behaviour to the differential resistance (Fig. 3b), with the same period of oscillations (ẟBz ≈ 0.8 mT) and the slope of the side branches. The slope of the side branches can be expressed as

From this and the value of the slope \(\frac{{B_x}}{{B_z}}\) extracted from the experiment, we find that at Bx = 12 mT, the Cooper pair momentum is 2qy ≈ 1.6 × 106 m–1.

Let us compare the estimate of the Cooper pair momentum based on the evolution of the interference pattern with the results of the JDE measurements mentioned above. The maximum JDE is achieved when the phase shift ẟ = 2qxd equals approximately 0.5π, which corresponds to the Cooper pair momentum 2qx = \(\frac{\delta }{d}\) ≈ 4.5 × 106 m−1 at Bx = 12 mT. Although the JDE and interference peak splitting are measured under in-plane magnetic fields along two orthogonal directions, the field-induced Cooper pair momenta 2qx and 2qy estimated from these measurements are of the same order of magnitude, further strengthening our conclusion that both effects arise from the FCPM.

It is remarkable that a JJ device comprising a centrosymmetric material such as NiTe2 exhibits a large JDE effect arising from finite-momentum pairing. There exist several possible mechanisms that could be responsible for FCPM in our experiment. One candidate is the current screening effect. This mechanism, which lies in the emergence of the finite-momentum Cooper pairing due to Meissner screening, has already been demonstrated to be able to give rise to FCPM31 and has been predicted to be responsible for a robust and large JDE in short junctions36. We estimate the value of finite-momentum Cooper pairing arising from screening in Nb contacts. The thickness of Nb leads (30 nm) is much smaller than the London penetration depth, and therefore, we estimate \(q_x \approx \frac{{{e}}}{\hbar }B_y\frac{{h_{{\mathrm{Nb}}}}}{2}.\) At By = 20 mT, this corresponds to 2qx ≈ 106 m–1. Since this is smaller than the observed value of Cooper pairing, it alone cannot account for the observed effect.

Another plausible origin of the FCPM is related to the Zeeman shift of the proximitized topological surface states of NiTe2. Previous studies23,24 have reported the presence of spin-polarized surface states in NiTe2 that cross the Fermi level. Here we have used ARPES to examine the detailed fermiology of these surfaces states and estimate their Fermi energy and velocity (Supplementary Sections IX and X). Figure 4a displays a close-up of the experimental Fermi surface, showing both sharp surface-state bands and diffuse bulk bands that are broadened due to the limited penetration depth of the photoelectrons. The full Fermi surface in the surface Brillouin zone of NiTe2 is shown in Fig. 4a (inset). A schematic representing the surface electron and hole pockets (indicated by green and orange lines, respectively) is shown in Fig. 4b,c, where the arrows indicate the spin texture. The electron-like and hole-like character of the Fermi surface pockets can be examined from the linecuts (Fig. 4d,e). The energy–momentum dispersion of two topological surface states along the \({{{\bar{\mathrm \Gamma }}}} - \bar M\) direction are shown in Fig. 4e, which is qualitatively reproduced by our ab initio calculations (Fig. 4f) that also indicate their spin polarization. Note that the calculation slightly underestimates the energy at which the lower-lying surface state merges with the valence-band bulk continuum in the experiment. The origin of these surface states is the band inversion of the valence and conduction bands above the Fermi level24,37, which leads to the formation of a spin-helical Dirac surface state that connects the conduction and valence bands (Fig. 4g), similar to the surface state in a topological insulator. The upper branch of this Dirac surface state forms an electron pocket with a relatively small Fermi energy (EF ≈ 15 meV) and Fermi velocity vF ≈ 0.4 × 105 m s–1, as well as a hole pocket with a larger Fermi velocity of 3.3 × 105 m s–1.

a, Close-up of the Fermi surface measured with ARPES using photon energy hv = 56 eV and horizontal linear polarization. The inset shows the larger fraction of the surface Brillouin zone measured with hv = 25 eV and horizontal linear polarization. b,c, Schematic of the surface electron (green lines) and hole (orange lines) pockets deduced from the ARPES data. The arrows in c show the spin texture of the surface states. d,e, ARPES dispersion along cut #1 (d) and cut #2 (e) (the cuts are shown in b), showing the electron (green lines) and hole (orange lines) character of the bands. The data shown in d were measured with 56 eV and those in e with 25 eV, both with horizontal linear polarization. f, DFT calculations of the energy–momentum dispersion along the \({{{\bar{\mathrm \Gamma }}}} - \bar M\) direction. Two surface states are highlighted, the line width is proportional to the surface contribution and the component of the spin polarization perpendicular to the momentum is shown in colour. g, Schematic showing the relative position of the dispersion of the surface states along the \({{{\bar{\mathrm \Gamma }}}} - \bar M\) direction with respect to the conduction and valence bands.

The data shown in Fig. 4d–g were used for deducing the spin structure of the surface states shown in Fig. 4b,c, which is in agreement with the experimental reports23,24,37. The spin texture of the surface states (Fig. 4c) clearly shows one (inner) helical hole state and one (outer) helical electron state. The helicity of the hole and electron states is opposite. In the presence of an in-plane magnetic field, the Fermi surfaces of these states shift in the same direction; furthermore, in the proximity of the superconductor, finite-momentum Cooper pairing is realized. The momentum shift of these states in a magnetic field can be substantial: the surface states of topological insulators can have large g-factors, for example, a g-factor of ~60 has been found in a previous report38. However, because of the complexity of the surface-state structure, we leave quantifying the FCPM to a further study. However, the presented analysis suggests that there will be a finite, and likely substantial, contribution of the spin–momentum-locked surface states of NiTe2 to the finite-momentum Cooper pairing.

In summary, we have shown that a JJ device involving a type-II Dirac semimetal NiTe2 exhibits a large non-reciprocal critical current in the presence of a small in-plane magnetic field oriented perpendicular to the supercurrent. The behaviour of the critical current together with the evolution of the interference pattern under the application of an in-plane magnetic field provides compelling evidence for finite-momentum Cooper pairing. Whether or not this mechanism is generic to the family of Dirac semimetals remains an open question.

Methods

Exfoliation of NiTe2 flakes

Thin NiTe2 flakes were exfoliated from a high-quality NiTe2 single crystal (from HQ Graphene) using a standard Scotch-tape exfoliation technique and placed on a Si(100) substrate with a 280-nm-thick SiO2 on top. Although NiTe2 is known to be very stable under ambient conditions39, the exfoliation was carried out in a glove box under a nitrogen atmosphere, with water and oxygen levels each below 1 ppm. The thinnest flakes were identified from their optical contrast in an optical microscope and subsequently used to prepare the devices.

Device fabrication and electrical measurements

All the devices used in our experiments were fabricated using an electron-beam-lithography-based method. Before exposure, each substrate was spin coated with an AR-P 679.03 resist at 4,000 rpm for 60 s followed by annealing at 150 °C for 60 s. After electron-beam exposure and subsequent development, contact electrodes were formed from sputter-deposited trilayers of 2 nm Ti/30 nm Nb/20 nm Au for the JJ devices. The contacts formed from 2 nm Ti/80 nm Au were deposited for the Hall bar devices.

Electrical transport measurements were performed in a Bluefors LD-400 dilution refrigerator with a base temperature of 20 mK and equipped with high-frequency electronic filters (QDevil ApS). Angle-dependent magnetic-field measurements were carried out using a 2D superconducting vector magnet integrated within the Bluefors system. A small consistent offset in the magnetic field, of the order of ~1.5 mT, was observed as the magnetic field was swept due to likely flux trapping within the superconducting magnet coils. Direct current (d.c.) voltage characteristics of the JJ devices were measured using a Keithley 6221 current source and a Keithley 2182A nanovoltmeter. Differential resistance measurements were performed using a Zurich Instruments MFLI lock-in amplifier with a multi-demodulator option using a standard low-frequency (3–28 Hz) lock-in technique. The critical currents for the Fraunhofer pattern were measured in combination with a Keithley 2636B voltage source to sweep the d.c. bias.

ARPES experiments

To explore the momentum-resolved electronic structure, ARPES measurements were carried out on a NiTe2 single crystal cleaved along the [0001] direction. All the experiments were carried out at the ULTRA endstation of the SIS beamline at the Swiss Light Source, Switzerland, with a Scienta Omicron DA30L analyser. Each crystal was cleaved in situ under ultrahigh vacuum at 20 K to ensure no contamination of the surface. The base pressure of the system was better than 1 × 10−10 mbar.

Calculation of evolution of interference pattern in an in-plane magnetic field

We calculate the Josephson current by considering the quasi-classical trajectories of Cooper pairs across the junction34 (Supplementary Fig. 12):

where

is the total phase difference for a trajectory that starts at (0, y1) and ends at (deff, y2), deff = d + 2λ and λ = 140 nm is the London penetration depth35. Further, Δφ0 is the phase difference between the order parameters in the two superconducting leads in the absence of an applied field. We have neglected the effect of the finite thickness of NiTe2.

To calculate the evolution of the interference pattern, we compute the Josephson current using the equation above and maximize it by varying Δφ0, which allows one to find Ic. To compare the theoretical and experimental predictions, we further adjust the value of the effective junction separation deff because of flux focusing34, which is carried out by calculating the Fraunhofer pattern at a zero in-plane magnetic field (giving a slightly different but still qualitatively similar dependence to \(\frac{{\sin \left( \frac{{\uppi {{\varPhi }}}}{{{{\varPhi }}_0}}\right) }}{\left({{\frac{{\uppi {{\varPhi }}}}{{{{\varPhi }}_0 }}}}\right)}\)) and by fitting the position of the first minimum to the experimental value. We find the linear dependence of the parameter qy(Bx) and the vertical scale of the theoretical plot by using the average slope of the side branches \(\frac{{B_x}}{{B_z}}\) from the experiment and matching it to the slope of the calculated pattern34: \(\frac{{2q_y}}{{B_z}} \approx \frac{{\uppi d_{{\mathrm{eff}}}}}{{{{\varPhi }}_0}}\).

DFT calculation of NiTe2 energy spectrum

For the Dirac semimetal NiTe2, the lattice parameters are a = b = 3.857 Å, c = 5.262 Å, α = β = 90° and γ = 120°. We first perform DFT calculations with the full-potential local-orbital program40. The band-structure calculation is done with a fine k-point mesh including up to 50 points. Since we are using atomic basis sets, a high-symmetry tight-binding Hamiltonian is constructed using the automatic Wannier projection flow41. The Bloch states are projected onto a small local basis set (34 bands for 3 atoms) around the Fermi level, which consists of 3d, 4s and 4p orbitals for Ni and 5s and 5p orbitals for Te. The projected tight-binding Hamiltonian perfectly reproduces the DFT band structures even up to 5 eV away from the Fermi level. The spin-projected surface states are calculated in a slab geometry with 10 to 20 layers from a Wannier tight-binding model.

Data availability

Source data are provided with this paper. All other data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Shockley, W. The theory of p-n junctions in semiconductors and p-n junction transistors. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 28, 435–489 (1949).

Braun, F. Ueber die Stromleitung durch Schwefelmetalle. Ann. Phys. 229, 556–563 (1875).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Josephson, B. D. Possible new effects in superconductive tunnelling. Phys. Lett. 1, 251–253 (1962).

Bal, M., Deng, C., Orgiazzi, J. L., Ong, F. R. & Lupascu, A. Ultrasensitive magnetic field detection using a single artificial atom. Nat. Commun. 3, 1324 (2012).

Vettoliere, A., Granata, C. & Monaco, R. Long Josephson junction in ultralow-noise magnetometer configuration. IEEE Trans. Magn. 51, 1–4 (2015).

Walsh Evan, D. et al. Josephson junction infrared single-photon detector. Science 372, 409–412 (2021).

Wallraff, A. et al. Strong coupling of a single photon to a superconducting qubit using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 431, 162–167 (2004).

Walsh, E. D. et al. Graphene-based Josephson-junction single-photon detector. Phys. Rev. Appl. 8, 024022 (2017).

You, J. Q., Tsai, J. S. & Nori, F. Scalable quantum computing with Josephson charge qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 197902 (2002).

Yu, Y., Han, S., Chu, X., Chu, S.-I. & Wang, Z. Coherent temporal oscillations of macroscopic quantum states in a Josephson junction. Science 296, 889–892 (2002).

Ioffe, L. B., Geshkenbein, V. B., Feigel’man, M. V., Fauchère, A. L. & Blatter, G. Environmentally decoupled sds-wave Josephson junctions for quantum computing. Nature 398, 679–681 (1999).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Wu, H. et al. The field-free Josephson diode in a van der Waals heterostructure. Nature 604, 653–656 (2022).

Baumgartner, C. et al. Supercurrent rectification and magnetochiral effects in symmetric Josephson junctions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 39–44 (2021).

Daido, A., Ikeda, Y. & Yanase, Y. Intrinsic superconducting diode effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 037001 (2022).

Yuan Noah, F. Q. & Fu, L. Supercurrent diode effect and finite-momentum superconductors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2119548119 (2022).

He, J. J., Tanaka, Y. & Nagaosa, N. A phenomenological theory of superconductor diodes. New J. Phys. 24, 053014 (2022).

Hu, J., Wu, C. & Dai, X. Proposed design of a Josephson diode. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 067004 (2007).

Misaki, K. & Nagaosa, N. Theory of the nonreciprocal Josephson effect. Phys. Rev. B 103, 245302 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Gu, Y., Hu, J. & Jiang, K. General theory of Josephson Diodes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.08901 (2022).

Scammell, H. D., Li, J. I. A. & Scheurer, M. S. Theory of zero-field superconducting diode effect in twisted trilayer graphene. 2D Mater. 9, 025027 (2022).

Mukherjee, S. et al. Fermi-crossing type-II Dirac fermions and topological surface states in NiTe2. Sci. Rep. 10, 12957 (2020).

Ghosh, B. et al. Observation of bulk states and spin-polarized topological surface states in transition metal dichalcogenide Dirac semimetal candidate NiTe2. Phys. Rev. B 100, 195134 (2019).

Kodama, J. I., Itoh, M. & Hirai, H. Superconducting transition temperature versus thickness of Nb film on various substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 54, 4050–4054 (1983).

Farrell, M. E. & Bishop, M. F. Proximity-induced superconducting transition temperature. Phys. Rev. B 40, 10786–10795 (1989).

Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity (Dover Publication, 2004).

de Gennes, P. G. & Mauro, S. Excitation spectrum of superimposed normal and superconducting films. Solid State Commun. 3, 381–384 (1965).

Clarke, J. The proximity effect between superconducting and normal thin films in zero field. J. Phys. Colloques 29, C2-3–C2-16 (1968).

Assouline, A. et al. Spin-orbit induced phase-shift in Bi2Se3 Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 10, 126 (2019).

Zhu, Z. et al. Discovery of segmented Fermi surface induced by Cooper pair momentum. Science 374, 1381–1385 (2021).

Yuan, N. F. Q. & Fu, L. Zeeman-induced gapless superconductivity with a partial Fermi surface. Phys. Rev. B 97, 115139 (2018).

Hart, S. et al. Controlled finite momentum pairing and spatially varying order parameter in proximitized HgTe quantum wells. Nat. Phys. 13, 87–93 (2017).

Chen, A. Q. et al. Finite momentum Cooper pairing in three-dimensional topological insulator Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 9, 3478 (2018).

Gubin, A. I., Il’in, K. S., Vitusevich, S. A., Siegel, M. & Klein, N. Dependence of magnetic penetration depth on the thickness of superconducting Nb thin films. Phys. Rev. B 72, 064503 (2005).

Davydova, M., Prembabu, S. & Fu, L. Universal Josephson diode effect. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo0309 (2022).

Clark, O. J. et al. Fermiology and superconductivity of topological surface states in PdTe2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 156401 (2018).

Xu, Y., Jiang, G., Miotkowski, I., Biswas, R. R. & Chen, Y. P. Tuning insulator-semimetal transitions in 3D topological insulator thin films by intersurface hybridization and in-plane magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 207701 (2019).

Nappini, S. et al. Transition-metal dichalcogenide NiTe2: an ambient-stable material for catalysis and nanoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2000915 (2020).

Koepernik, K. & Eschrig, H. Full-potential nonorthogonal local-orbital minimum-basis band structure scheme. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1743–1757 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Different types of spin currents in the comprehensive materials database of nonmagnetic spin Hall effect. npj Comput. Mater. 7, 167 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Kontos and S.-H. Yang for valuable discussions. S.S.P.P. acknowledges the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project no. 443406107, Priority Programme (SPP) 2244. The work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was supported by a Simons Investigator Award from the Simons Foundation. L.F. was partly supported by the David and Lucile Packard foundation. J.A.K. acknowledges support by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF grant no. P500PT_203159). We acknowledge the Paul Scherrer Institut for provision of synchrotron radiation beam time at the ULTRA end station of the SIS Beamline at the Swiss Light Source and we thank N. Plumb, M. Shi, M. Radovic, A. Pfister, L. Nue and H. Li for their help with the ARPES measurements. We thank Saumya Mukherjee for sharing with us his raw ARPES data from NiTe2.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.S.P. and B.P. conceived the project. A.C. and B.P. performed the exfoliation and fabricated the JJ and Hall bar devices. B.P. and P.K.S. perfomed all the electrical measurements. A.C., A.K.G. and A.K.P. characterized the flakes. M. Davydova, Y.Z., N.Y. and L.F. performed the phenomenological, theoretical and DFT calculations. J.A.K., M. Date, S.J., B.P. and N.B.M.S. collected the ARPES data. B.P. and N.B.M.S. performed the ARPES analysis. S.S.S.P., B.P., N.B.M.S., M.D. and L.F. wrote the manuscript with help from all the co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections I–X and Figs. 1–16.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

All the combined line plots of Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

All the combined line plots of Fig. 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pal, B., Chakraborty, A., Sivakumar, P.K. et al. Josephson diode effect from Cooper pair momentum in a topological semimetal. Nat. Phys. 18, 1228–1233 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01699-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-022-01699-5

This article is cited by

-

Intrinsic supercurrent non-reciprocity coupled to the crystal structure of a van der Waals Josephson barrier

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Superconducting diode effect sign change in epitaxial Al-InAs Josephson junctions

Communications Physics (2024)

-

Magnetic field filtering of the boundary supercurrent in unconventional metal NiTe2-based Josephson junctions

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Parity-conserving Cooper-pair transport and ideal superconducting diode in planar germanium

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Superconducting tunnel junctions with layered superconductors

Quantum Frontiers (2024)