Abstract

The aim of this study was to characterize the mutational landscape of patients with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated within the randomized CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial evaluating intensive chemotherapy plus the multi-kinase inhibitor midostaurin versus placebo. We performed sequencing of 262 genes in 475 patients: mutations occurring concurrently with the FLT3-mutation were most frequent in NPM1 (61%), DNMT3A (39%), WT1 (21%), TET2 (12%), NRAS (11%), RUNX1 (11%), PTPN11 (10%), and ASXL1 (8%) genes. To assess effects of clinical and genetic features and their possible interactions, we fitted random survival forests and interpreted the resulting variable importance. Highest prognostic impact was found for WT1 and NPM1 mutations, followed by white blood cell count, FLT3 mutation type (internal tandem duplications vs. tyrosine kinase domain mutations), treatment (midostaurin vs. placebo), ASXL1 mutation, and ECOG performance status. When evaluating two-fold variable combinations the most striking effects were found for WT1:NPM1 (with NPM1 mutation abrogating the negative effect of WT1 mutation), and for WT1:treatment (with midostaurin exerting a beneficial effect in WT1-mutated AML). This targeted gene sequencing study provides important, novel insights into the genomic background of FLT3-mutated AML including the prognostic impact of co-mutations, specific gene–gene interactions, and possible treatment effects of midostaurin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mutations of FLT3 (fms-related tyrosine kinase 3) are common gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). They are found in 10–30% of patients, with a decreasing prevalence with older age [1, 2]. FLT3 encodes a receptor-tyrosine kinase that is expressed on hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and regulates cellular proliferation and apoptosis through downstream signaling pathways such as STAT5, RAS/MAPK, and PI3K/Akt [3]. Mutations of FLT3 encompass internal tandem duplications (ITD), most frequently located in the juxtamembrane region, as well as point mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), both promoting ligand-independent, constitutive receptor activation [4]. ITD but not TKD mutations have been consistently linked to a higher relapse rate and an inferior overall survival [5,6,7]. Yet, the prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD is context-dependent and influenced by the mutational background, for example whether a concurrent NPM1 mutation is present or not, the location of the ITD insertion site, and the mutant to wildtype allelic ratio (AR) [5, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The prognostic significance of the NPM1 mutational status and of the FLT3-ITD AR is implemented in the 2017 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk stratification [15].

The successful development of first- and next-generation FLT3 inhibitors has contributed to a new era for precision medicine in AML [16]. In the international CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial, the addition of the oral multi-targeted small molecule FLT3 inhibitor midostaurin to intensive induction and consolidation chemotherapy, followed by a 1-year midostaurin maintenance therapy, improved overall survival of patients 18 to 59 years of age with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated AML [17]. Midostaurin showed consistent effects across all FLT3 mutation strata, TKD, and ITD independent of the AR [17]. In addition, in the AMLSG 16–10 trial midostaurin significantly improved outcome also in older patients 60 to 70 years of age in comparison to a historical control cohort [18].

We previously reported on the impact of NPM1/FLT3-ITD genotypes as defined by 2017 ELN risk categories and of FLT3-TKD mutations in patients of the RATIFY trial [12, 19]. The objective of the current study was to comprehensively profile the mutational landscape of FLT3-mutated AML in patients treated within the RATIFY trial using a high-throughput targeted sequencing (HTS) approach, and to correlate genetic patterns with clinical outcomes.

Patients and methods

Patients

Overall, 717 patients with AML and FLT3 mutation were enrolled in the CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial [17]. HTS was performed on 475 patients (n = 409 bone marrow, n = 66 peripheral blood) who gave informed consent for further molecular studies and for whom DNA was available (Supplementary Table S1). Patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. FLT3 mutation status was available for all 475 pts (TKD: n = 116; 24%; ITD: n = 335; 71%; TKD + ITD: n = 24; 5%) and information on the AR (0.05–0.5: n = 126; ≥0.5: n = 232) for all but one patient with ITD. For analyses, patients (n = 24) harboring both FLT3-TKD and -ITD mutations were assigned to the ITD group based on the prognosis-defining features of ITD compared to TKD mutations.

In the RATIFY trial, patients 18 to 59 years of age were randomly assigned to receive standard chemotherapy plus either midostaurin or placebo. Randomization was stratified according to the subtype of FLT3 mutation: TKD or ITD with either a low (0.05 to 0.7) or a high AR (>0.7). For this analysis, a threshold of 0.5 (low, 0.05 to <0.5; high, ≥0.5) was chosen as this cutoff has been demonstrated to better discriminate clinical outcome and was adopted in the 2017 ELN risk classification [15]. 253 (53%) of 475 patients were randomized to the midostaurin arm and 222 patients to the placebo arm. 128 (27%) of the patients underwent allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) in first complete remission (CR).

The study was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center. Written consent was given by all patients for treatment, genetic analysis, and biobanking according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Gene mutation analyses

HTS was performed on the entire coding region of 262 genes involved in hematologic malignancies including 20 kinases targeted by midostaurin [20]. A comprehensive list of all genes is included in the Supplementary Appendix (Supplementary Tables S2, S3). Library enrichment was performed using SureSelectXT from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA, USA). Paired-end sequencing (read length: 2 × 100 base pairs) was carried out on a HiSeq 2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). All sequencing data were analyzed using an in-house computational pipeline [21]. Detailed information on the mutation calling and data curation workflow is provided in the Supplementary Information. FLT3 mutations were assessed by GeneScan-based fragment-length analysis as previously described [17].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.6.3. Fisher’s exact test and chi-squared test were employed for two-group comparisons of categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the distributions of time-to-event endpoints event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS). Associations between clinical and genetic variables and time-to-event endpoints were analyzed using log rank test and random survival forests.

Additionally, for the analysis of genomic classes log rank tests and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used, for which the proportional hazards assumption was checked via graphical methods. The covariables age, gender, ECOG performance status (0–1 vs. 2), WBC count on log2 scale, treatment arm, allogeneic HCT in first remission (as time-dependent variable), FLT3-mutation status as well the genomic classes (NPM1, chromatin-spliceosome, no class, TP53-aneuploidy, and core-binding factor (CBF) AML) were introduced into the multivariable regression model.

An effect was considered significant if P ≤ 0.05. As the proportion of missing values in covariates used for modeling was very low (1 missing observation in FLT3 allelic ratio, 3 missings in white blood cell count [WBC]), single imputation was employed using chained equations as implemented in the mice package [22]. Clinical endpoints were assessed as defined by the 2017 ELN recommendations [15, 17].

Correction for multiple testing was implemented via the Bonferroni-Holm and the Benjamini–Hochberg method, depending on the number of tests [23, 24]. An effect was considered significant if the adjusted P ≤ 0.05.

Mutual exclusivity and co-occurrence of genomic mutations were tested via independence tests while accounting for varying mutation rates via the method proposed by Canisius et al. and implemented in the Rediscover R package [25].

Random survival forests were implemented using the R package randomForestSRC to assess possible interactions of clinical and genetic variables [26]. One-hundred forests with distinct seeds were fitted on the imputed dataset hereby growing 1000 trees for each forest. Tree nodes were split using log rank statistics. The impact of a variable was ranked by the variable importance (VIMP) based on the prediction error calculated using Harrell’s C-index [27]. The assessment of pairwise interactions between variables was based on the comparison of the joint (“paired”) VIMP to the sum of their individual VIMPs (called “additive” importance): A large positive or negative difference between “additive” and “paired” importance indicates a possibly relevant association.

Results

Mutational landscape of FLT3-mutated AML

High-throughput sequencing of the 475 FLT3-mutated AML yielded a mean on-target sequencing depth of ~975×. Overall, we found 1988 mutations with a variant allele fraction of equal to or greater than 3% in 200 of the 262 genes. At least one mutation in addition to FLT3-ITD or -TKD was identified in 463 of 475 (97.5%) patients. The overall median number of additional mutations per patient was 3 and—when stratified by mutation type—4 in the TKD vs. 3 in the ITD group. The majority of mutations were missense mutations (49%) and indels (40%). 26 (5.5%) of patients had non-canonical FLT3 mutations outside of TKD and ITD mutational hotspots, including 14 with mutations in exon 16 (codon 663–680), that were missed by GeneScan-based fragment-length analysis. 4 of 14 were concurrent with ITDlow and 10 of them with TKD mutations. Overall, the most frequently affected genes were NPM1 (291, 61%), DNMT3A (187, 39%), WT1 (100, 21%), TET2 (55, 12%), NRAS (53, 11%), RUNX1 (53, 11%), PTPN11 (45, 10%), IDH1 (39, 8%), ASXL1 (38, 8%), IDH2 (34, 7%), SMC1A (28, 6%), CEBPA (26, 5%), and SMC3 (24, 5%) (Figs. 1, 2; Table S4).

Each column represents a single patient, each dark gray colored box indicates a specified driver mutation or cytogenetic feature. Wildtype cases are illustrated in beige, FLT3-ITD mutations in dark red, FLT3-TKD mutations in blue. Bar plots indicate the relative frequency of all aberrations in the entire cohort. CK complex karyotype, NA not available, NK normal karyotype.

Frequency of gene mutations by FLT3 mutation type

NRAS (28, 24% vs. 25, 7%, p < 0.001), SMC1A (12, 10% vs. 16, 4%, p = 0.02), and KIT (5, 4% vs. 3, 1%, p = 0.02) mutations occurred significantly more often in TKD than ITD groups, respectively, whereas WT1 (15, 13% vs. 84, 24%, p = 0.018) was more frequently co-mutated in the ITD group (Fig. 2A, Table S4).

Frequency of mutations by functional classes (signaling, methylation, chromatin, cohesin, transcription, tumor suppressor, splicing, other)

In 29% (138) of cases we identified mutations affecting other signaling molecules, most commonly in NRAS (53, 11%), PTPN11 (45, 10%), KRAS (13, 3%), and KIT (8, 2%) (categorization in Table S5). These additional signaling mutations more often co-occurred in the FLT3-TKD than -ITD group (50, 43% vs. 90, 25%, p = 0.001). In general, mutations altering DNA methylation pathways were common (total: 264, 56%; DNMT3A: 187, 39%, TET2: 55, 12%, IDH1: 39, 8%, IDH2R140: 34, 7%). Other frequently altered functional groups of genes involved chromatin modification (ASXL1: 38, 8%, KMT2D: 18, 4%) and the cohesin complex (SMC1A: 28, 6%, SMC3: 24, 5%, RAD21: 23, 5%, STAG2: 18, 4%). Among genes regulating transcription, we found recurrent loss-of-function mutations in NFE2 (13, 3%) and codon 73–78 hotspot mutations in MYC (15, 3%), as well as aberrations of WT1 (100, 21%), RUNX1 (53, 11%), CEBPA (26, 5%), BCOR (20, 4%), BCORL1 (16, 3%), ZBTB7A (15, 3%), and GATA2 (14, 3%). Mutations in TP53 (4, 0.8%) and in genes encoding for splicing factors (SF3B1: 9, 1.9%, SRSF2: 8, 1.7%, U2AF1: 4, 0.8%, ZRSR2: 1, 0.2%) were rare reflecting the de novo disease onset in the vast majority of cases (455, 96%) and the younger age of the patients.

The top 12 most frequently mutated genes were tested for mutual exclusivity (66 possible combinations) resulting in 21 significant pairs before adjustment for multiple testing and 5 significant pairs after FDR adjustment: NPM1-RUNX1 (p < 0.001), DNMT3A-WT1 (p < 0.001), DNMT3A-RUNX1 (p = 0.003), NPM1-WT1 (p = 0.008) and IDH2-TET2 (p = 0.021). Similarly, all combinations were tested for co-occurrence resulting in 2 significant pairs before adjustment for multiple testing: NPM1-DNMT3A and IDH1-PTPN11, which were not significant after FDR adjustment (Fig. S1).

Classification of cases according to genomic AML classes

Using the mutational and cytogenetic data, we assigned cases to the genomic AML classes as previously defined (Fig. 1; Tables S6, 7) [1]. This was possible for 451 of 475 patients, in which the complete mutational and cytogenetic dataset was available or at least one class-defining aberration was present. The majority of cases fell into three classes: NPM1 (287, 60%), chromatin-spliceosome (68, 14%), and no class (60, 13%). All other AML classes were less frequent: TP53-aneuploidy (18, 4%), inv(16) (10, 2%), t(8;21) (8, 2%), t(11q23;x) (8, 2%), t(6;9) (4, 1%), and CEBPAbiallelic (3, <1%). Due to these low sample sizes, we restricted further statistical analyses to the following genomic classes: NPM1, chromatin-spliceosome, no class, TP53-aneuploidy, and the core-binding factor (CBF) AML class [inv(16) and t(8;21)], thereby excluding a total of 24 patients in the smaller categories resulting in a total of 451 patients for analysis.

Mutations of midostaurin kinome genes

In addition, we screened 20 kinase genes (Table S3) known to be pharmaceutically targeted by midostaurin. Pretreatment mutations in the midostaurin kinome were rare events with only 40 mutations in 35 of 475 patients (7%). The most frequently affected genes were KIT (8, 2%), NTRK3 (4, 0.8%), and MAP3K11 (4, 0.8%) (Fig. 2B).

Clinical impact of molecular landscape in FLT3-mutated AML

Prognostic and predictive impact of concurrent gene mutations

We first performed exploratory unvariable analysis for genes that were mutated in more than 5% of 475 cases. Five of twelve mutations showed an association with outcome: mutations in ASXL1 (p = 0.0125; hazard ratio (HR): 1.67, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.11–2.52) and WT1 (p < 0.001; HR: 1.83, 95%CI: 1.38–2.43) were associated with a significantly shortened OS (Table S8 and Figs. S2, 3), whereas NPM1 (p < 0.001; HR: 0.6, 95%CI: 0.46–0.77) and in trend NRAS (p = 0.097; HR: 0.68, 95%CI: 0.43–1.08) mutations conferred a favorable prognosis. After adjusting for multiple testing via Bonferroni-Holm procedure, only NPM1 and WT1 mutations retained significance at the 5% level. With respect to EFS, WT1 (p = 0.018; HR: 1.36, 95%CI: 1.05–1.75), and in trend SMC1A (p = 0.075; HR: 0.64, 95%CI: 0.38–1.05) conferred poor prognosis in univariate analysis, whereas only NPM1 (p < 0.001; HR: 0.6, 95%CI: 0.48–0.74) prolonged survival, both in univariate analysis and after adjustment for multiple testing (Table S8, and Figs. S2, 3).

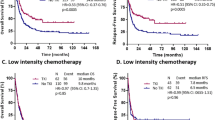

To assess prognostic effects of both clinical features and genetic variables we fitted random survival forests. To quantify the random variability, a total of 100 forests with different seeds were trained hereby constructing 1000 trees for each forest. The impact of a variable was measured using the variable importance (VIMP) in each forest which reflects the loss in the model’s prediction accuracy after permutation of each variable/feature. The higher the VIMP, the higher the prognostic and/or predictive value of the variable. With respect to OS, highest VIMP was found for WT1 and NPM1 mutations, followed by WBC count, FLT3 mutation type, treatment (midostaurin vs. placebo), ASXL1 mutation, and ECOG performance status (0–1 vs. 2) in descending order (Fig. 3A). With regard to EFS, random forest indicated a higher VIMP only for NPM1, WBC count, sex, and FLT3 mutation status (Fig. 3B). The unfavorable impact of WT1 mutations on OS was predominantly observed across the intermediate and adverse ELN 2017 groups (Figs. S4, 5).

Prognostic and potential predictive impact of 18 most relevant clinical and/or genetic variables (A, B) and pairwise interactions (C, D) in 475 patients on overall and event-free survival using random survival forests. The prognostic impact of a variable is measured via VIMP (variable importance). Higher VIMP values indicate that a variable may have prognostic impact on the survival endpoint. EFS event-free survival, OS overall survival.

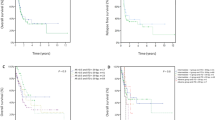

To assess the potential impact of specific gene–gene or gene-clinical variable interactions, resulting random forests were also used to identify relevant pairwise interactions among all paired combinations of mutations, midostaurin treatment, and gender. With regard to OS, the most striking interactions were observed for WT1:NPM1 and WT1:treatment (Figs. 3C, S6). For the ten most relevant interactions we created Kaplan–Meier estimators for further illustration (Figs. 4, S7, 8). There were two important observations: first, the prognostic influence of some gene mutations was severely dependent on the mutational background: As aforementioned, outcome of patients harboring NPM1 mutations was particularly favorable, whereas WT1 mutations were linked to poor prognosis. In case of mutational co-occurrence, the presence of NPM1 seemed to extensively abrogate the negative impact of WT1 (Fig. 4A). Patients who had both NPM1 and SMC1A mutations had a particularly good outcome, outreaching the prognosis of patients with the NPM1mut/SMC1Awt genotype. Yet, in the absence of NPM1 aberrations, all 5 patients with SMC1A-mutated AML died within 3 years (Fig. 4B). Second, specific genotypes in FLT3-mutated AML seemed to benefit particularly from therapy with midostaurin, in particular those patients with concurrent WT1 mutation. In contrast, WT1-mutated patients randomized to the placebo arm had a very poor prognosis suggesting a particular benefit of midostaurin in the presence of WT1-mutations (Fig. 4C).

Of note; in line with previous data, FLT3 was frequently co-mutated with DNMT3A and NPM1 (n = 157; 33%). [1, 28,29,30] In our cohort, no relevant interaction could be observed for the combined FLT3:DNMT3A:NPM1 genotype with regard to clinical outcome (OS, EFS) (Figs. 3C, D, S9).

Prognostic impact of FLT3 mutations by AML genomic class

In 451 of 475 cases that could be subclassified into genomic classes, we found significant differences in longterm survival among the five genomic AML classes (OS: p < 0.001, EFS: p < 0.001) (Fig. S10, Tables S9, 10). Estimated 4-year-survival rates were highest for CBF-AML (OS: 72%, EFS: 50%) followed by NPM1 classes (OS: 57%, EFS: 38%), whereas patients of the chromatin-spliceosome (OS: 33%, EFS: 16%), TP53-aneuploidy (OS: 35%, EFS: 6%), and no class (OS: 37%, EFS: 10%) groups had an adverse OS and EFS. Although patients of the ‘no class’ group were younger, they had a higher frequency of FLT3-ITD, in particular with a high ITD AR, WT1 co-mutations, and less often a normal karyotype, possibly explaining the poorer outcome (Fig. 1, Table S7).

Next, we developed a prognostic proportional hazard model including the 5 genomic AML classes, as well as the covariates age, gender, ECOG performance status (0–1 vs. 2), log2 WBC count, FLT3-status (TKD, ITDlow, ITDhigh), treatment (midostaurin, placebo), and allogeneic HCT in first CR1 as a time-dependent variable. In line with univariate analyses, we observed poorer OS and EFS in the TP53-aneuploidy, chromatin-spliceosome and no class genomic groups compared to the reference NPM1 group (Fig. 5). CBF-AML patients seemed to have a more favorable outcome than the NPM1 reference group, although not statistically significant likely due to the small sample size. With regard to the FLT3-status, patients with FLT3-ITDhigh had inferior outcome compared to the FLT3-TKD mutated group. In addition, higher WBC counts conferred poor OS and EFS: A doubling was associated with an almost 10% higher risk of an event or death. Treatment with midostaurin and allogeneic HCT in CR1 both had a positive impact on OS, midostaurin in addition on EFS (Fig. 5).

Cox proportional hazard model for prognostic impact of genomic AML classes and clinical features on (A) overall and (B) event-free survival in the cohort of 451 of 475 patients, in which subcategorization into genomic AML classes was possible. A hazard ratio of >1 indicates a higher and a hazard ratio of <1 a lower hazard of death or event, respectively. The NPM1 class was used as reference group, allogeneic HCT in first remission as time-dependent variable. ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, HCT hematopoietic cell transplantation, WBC white blood cell count.

Finally, we assessed whether the genomic classification had a predictive impact on the hazard of death after midostaurin treatment. Treatment with midostaurin prolonged OS in the NPM1, chromatin-spliceosome and in the no class groups (Table 2). This was not the case for TP53-aneuploidy and CBF-AML classes (Table 2, Figs. S11, 12). However, data need to be interpreted with caution due to the limited sample size. With regard to OS and EFS, similar treatment effects of midostaurin were observed across all FLT3 mutation strata substantiating the therapeutic benefit irrespective of the FLT3 mutation type (Table S11; Fig. S13).

Discussion

In this study we characterized the mutational landscape and its clinical significance in 475 patients with FLT3-mutated AML enrolled on the pivotal CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial evaluating intensive chemotherapy with or without midostaurin.

The most frequent gene mutations co-occurring with FLT3 mutations were, in order of decreasing frequency, mutations in NPM1, DNMT3A, WT1, TET2, NRAS, RUNX1, PTPN11, IDH1, ASXL1, IDH2, SMC1A, CEBPA, and SMC3 genes. Compared to the general AML population, mutations in WT1 were overrepresented which is in line with previous studies showing this particular co-mutation pattern [31, 32]. In contrast, mutations in TP53, and in genes encoding for splicing factors (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2) were less common, likely reflecting differences in disease biology—e.g., high frequency of normal karyotypes and NPM1 mutations generally observed in FLT3-mutated AML—and age distribution (median age 47.9 years) compared to the median age of the general AML population of about 70 years [33].

To assess prognostic and potentially predictive effects of gene mutations in the context of clinical covariates, we fitted random forests. Here, the highest prognostic effect was found for WT1 and NPM1 mutations, followed by WBC count, FLT3 mutation type (ITD vs. TKD mutations), treatment (midostaurin vs. placebo), ASXL1 mutation, and ECOG performance status. The prognostic effect of NPM1 mutations, especially in the context of concurrent FLT3-ITD, is well established and reflected in the 2017 ELN risk stratification [15]. The results from this study provide additional novel and clinically relevant data, in that mutations in WT1 and ASXL1 have independent prognostic value in the context of AML with FLT3 mutations. In previous studies in pediatric AML and in cytogenetically-normal adult AML, the presence of WT1 mutations has been linked to primary resistance to therapy and shortened survival [34,35,36,37]. Here, the unfavorable effect was most pronounced in the intermediate and adverse ELN risk group, whereas the effect in the favorable-risk group was largely mitigated by the concurrent presence of NPM1 mutation. WT1 is a co-transcriptional factor involved in epigenetic regulation [38]. Several groups have reported that WT1 physically interacts with TET2 to modulate 5-hydroxymethylation of cytosine, a pathway commonly dysregulated in AML [39, 40]. Interestingly, in a recent study Pronier et al. have demonstrated that WT1 haploinsufficiency cooperates with FLT3-ITD to induce leukemogenesis in vivo [41].

Extending on the random forest model, when analyzing pairwise interactions the most striking interactions were observed for WT1:NPM1 and WT1:treatment. The presence of NPM1 mutations seemed to largely abrogate the negative impact of WT1 mutations. A similar observation has previously been made for other NPM1 co-mutation patterns, e.g., NPM1:FLT3-TKD, in that NPM1 mutation abrogates the negative prognostic effect of a FLT3-TKD mutation [19, 42,43,44]. With regard to treatment effects, patients with FLT3:WT1 co-mutations appeared to benefit from the addition of midostaurin; overall, patients with FLT3:WT1 co-mutations had poor outcomes, however, patients with FLT3:WT1 co-mutations on the midostaurin arm had similar longterm survival compared to patients with the FLT3mut/WT1wt genotype treated on the placebo arm. Another new finding relates to the FLT3:NPM1:SMC1A gene–gene interaction. Patients who had co-mutation of both NPM1 and SMC1A genes had a particularly good outcome, outreaching the prognosis of patients with the FLT3mut/NPM1mut/SMC1Awt genotype. Yet, in the absence of NPM1 mutations all patients harboring a SMC1A mutation died. Little is known about the biological basis of SMC1A mutations in the context of NPM1 and FLT3 mutations. However, AML with concurrent cohesin and NPM1 gene mutations define a specific cluster within the group of NPM1 mutated AML, that is reflected by a distinct metabolic gene signature [45]. Whether or not these features render the NPM1mut/SMC1Amut genotype more susceptible to treatment with chemotherapy ± midostaurin remains to be determined. Another similar gene–gene interaction with a cohesin complex gene was previously found with the interaction of NPM1 with RAD21 mutations, i.e., AML with the NPM1mut/RAD21mut genotype have been shown to be associated with high response rates and favorable longterm outcome [1]. Although these findings are very interesting and provide basis for further studies, they have to be interpreted cautiously due to small numbers.

In line with previous reports, the FLT3:DNMT3A:NPM1 genotype represented a common co-mutational pattern in our study. Data on the impact of FLT3:DNMT3A:NPM1 genotypes are still discussed controversially—with some publications showing evidence of poor outcome whereas others do not [1, 28,29,30]. Differences may be explained by variations in cohort size and features (e.g., age distribution), treatment, and genotypes (DNMT3A total vs. DNMT3A non-R882 vs. R882, FLT3 total vs. FLT3-ITD). In our study the FLT3:DNMT3A:NPM1 genotype did not impact clinical outcome. However, the analysis might be hampered by the size and heterogeneity of this specific subpopulation.

Based on the co-mutational and cytogenetic data we categorized the majority of the cases into four of the recently defined genomic AML classes [1] and evaluated whether the underlying class impacted response to therapy with midostaurin. A strong beneficial effect was seen for midostaurin treatment in the NPM1, chromatin-spliceosome and to a lesser extent “no class” groups. No impact of midostaurin was found for CBF- and TP53/aneuploidy groups which is likely attributable to the small group sizes. Overall, these results suggest a broad beneficial effect of midostaurin across various genetic backgrounds.

In conclusion, our targeted gene sequencing study in more than 450 patients with FLT3 mutation entered on the randomized CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial provides important and novel insights into the genomic background of FLT3-mutated AML, on prognostic impact of mutations co-occurring with FLT3 mutations as well as specific gene–gene interactions, and about possible treatment effects of midostaurin. Despite some limitations (e.g., the study was not powered for genetic subgroup analysis and results are of exploratory nature) our study provides the basis for future studies and validation of the findings in an independent dataset. Here, randomized trials comparing midostaurin with next-generation FLT3 inhibitors in patients with FLT3 mutations (e.g., NCT04027309) are currently underway and likely will provide additional valuable data with regard to the underlying genetic landscape and its clinical implications.

Data availability

A Supplementary Appendix accompanies this paper on the Leukemia website. Mutational data are available as.xlsx file as part of the Supplementary Information. Raw data were generated at the University of Ulm and are available on request from the corresponding author (KD).

References

Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–21.

Grimwade D, Ivey A, Huntly BJP. Molecular landscape of acute myeloid leukemia in younger adults and its clinical relevance. Blood. 2016;127:29–41.

Matthews W, Jordan CT, Wiegand GW, Pardoll D, Lemischka IR. A receptor tyrosine kinase specific to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell-enriched populations. Cell. 1991;65:1143–52.

Grafone T, Palmisano M, Nicci C, Storti S. An overview on the role of FLT3-tyrosine kinase receptor in acute myeloid leukemia: biology and treatment. Oncol Rev. 2012;6:e8.

Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, Schaich M, Schakel U, Platzbecker U, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–35.

Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, Harrison G, Langabeer SE, Belton AA, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United King. Blood. 2001;98:1752–9.

Frohling S, Schlenk RF, Breitruck J, Benner A, Kreitmeier S, Tobis K, et al. Prognostic significance of activating FLT3 mutations in younger adults (16 to 60 years) with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: a study of the AML Study Group Ulm. Blood. 2002;100:4372–80.

Pratcorona M, Brunet S, Nomdedeu J, Ribera JM, Tormo M, Duarte R, et al. Favorable outcome of patients with acute myeloid leukemia harboring a low-allelic burden FLT3-ITD mutation and concomitant NPM1 mutation: relevance to post-remission therapy. Blood. 2013;121:2734–8.

Kayser S, Schlenk RF, Londono MC, Breitenbuecher F, Wittke K, Du J, et al. Insertion of FLT3 internal tandem duplication in the tyrosine kinase domain-1 is associated with resistance to chemotherapy and inferior outcome. Blood. 2009;114:2386–92.

Gale RE, Green C, Allen C, Mead AJ, Burnett AK, Hills RK, et al. The impact of FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutant level, number, size, and interaction with NPM1 mutations in a large cohort of young adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2776–84.

Linch DC, Hills RK, Burnett AK, Khwaja A, Gale RE. Impact of FLT3(ITD) mutant allele level on relapse risk in intermediate-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2014;124:273–6.

Döhner K, Thiede C, Jahn N, Panina E, Gambietz A, Larson RA, et al. Impact of NPM1/FLT3-ITD genotypes defined by the 2017 European LeukemiaNet in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2020;135:371–80.

Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Bullinger L, Kobbe G, Casper J, Ringhoffer M, et al. Differential impact of allelic ratio and insertion site in FLT3-ITD-positive AML with respect to allogeneic transplantation. Blood. 2014;124:3441–9.

Rücker FG, Du L, Luck TJ, Benner A, Krzykalla J, Gathmann I, et al. Molecular landscape and prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD insertion site in acute myeloid leukemia: RATIFY study results. Leukemia. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-021-01323-0.

Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–47.

Döhner H, Wei AH, Löwenberg B. Towards precision medicine for AML. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18:577–90.

Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, Laumann K, Geyer S, Bloomfield CD, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:454–64.

Schlenk RF, Weber D, Fiedler W, Salih HR, Wulf G, Salwender H, et al. Midostaurin added to chemotherapy and continued single-agent maintenance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3-ITD. Blood. 2019;133:840–51.

Voso MT, Larson RA, Jones D, Marcucci G, Prior T, Krauter J, et al. Midostaurin in patients with acute myeloid leukemia and FLT3-TKD mutations: a subanalysis from the RATIFY trial. Blood Adv. 2020;4:4945–54.

Manley PW, Caravatti G, Furet P, Roesel J, Tran P, Wagner T, et al. Comparison of the kinase profile of midostaurin (Rydapt) with that of its predominant metabolites and the potential relevance of some newly identified targets to leukemia therapy. Biochemistry. 2018;57:5576–90.

Jahn N, Terzer T, Sträng E, Dolnik A, Cocciardi S, Panina E, et al. Genomic heterogeneity in core-binding factor acute myeloid leukemia and its clinical implication. Blood Adv. 2020;4:6342–52.

van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;1. https://www.jstatsoft.org/v045/i03.

Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1995;57:289–300.

Canisius S, Martens JWM, Wessels LFA. A novel independence test for somatic alterations in cancer shows that biology drives mutual exclusivity but chance explains most co-occurrence. Genome Biol. 2016;17:261.

Ishwaran H, Kogalur UB, Blackstone EH, Lauer MS. Random survival forests. Ann Appl Stat. 2008;2:841–60.

Harrell FEJ, Califf RM, Pryor DB, Lee KL, Rosati RA. Evaluating the yield of medical tests. JAMA. 1982;247:2543–6.

Bezerra MF, Lima AS, Piqué-Borràs M-R, Silveira DR, Coelho-Silva JL, Pereira-Martins DA, et al. Co-occurrence of DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3 mutations identifies a subset of acute myeloid leukemia with adverse prognosis. Blood 2020;135:870–5.

Thol F, Damm F, Lüdeking A, Winschel C, Wagner K, Morgan M, et al. Incidence and prognostic influence of DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2889–96.

Gaidzik VI, Schlenk RF, Paschka P, Stölzle A, Späth D, Kuendgen A, et al. Clinical impact of DNMT3A mutations in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of the AML Study Group (AMLSG). Blood. 2013;121:4769–77.

Gaidzik VI, Schlenk RF, Moschny S, Becker A, Bullinger L, Corbacioglu A, et al. Prognostic impact of WT1 mutations in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a study of the German-Austrian AML Study Group. Blood. 2009;113:4505–11.

Buelow DR, Pounds SB, Wang Y-D, Shi L, Li Y, Finkelstein D, et al. Uncovering the genomic landscape in newly diagnosed and relapsed pediatric cytogenetically normal FLT3-ITD AML. Clin Transl Sci. 2019;12:641–7.

National Cancer Institute. SEER cancer stat facts: acute myeloid leukemia. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/amyl.html. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; Accessed 13 May 2021.

McNeer NA, Philip J, Geiger H, Ries RE, Lavallée V-P, Walsh M, et al. Genetic mechanisms of primary chemotherapy resistance in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2019;33:1934–43.

Virappane P, Gale R, Hills R, Kakkas I, Summers K, Stevens J, et al. Mutation of the Wilms’ tumor 1 gene is a poor prognostic factor associated with chemotherapy resistance in normal karyotype acute myeloid leukemia: the United Kingdom Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5429–35.

Paschka P, Marcucci G, Ruppert AS, Whitman SP, Mrózek K, Maharry K, et al. Wilms’ tumor 1 gene mutations independently predict poor outcome in adults with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia: a cancer and leukemia group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4595–602.

Wang Y, Weng W-J, Zhou D-H, Fang J-P, Mishra S, Chai L, et al. Wilms tumor 1 mutations are independent poor prognostic factors in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol. 2021;11:632094.

Rampal R, Figueroa ME. Wilms tumor 1 mutations in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2016;101:672–9.

Rampal R, Alkalin A, Madzo J, Vasanthakumar A, Pronier E, Patel J, et al. DNA hydroxymethylation profiling reveals that WT1 mutations result in loss of TET2 function in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell Rep. 2014;9:1841–55.

Wang Y, Xiao M, Chen X, Chen L, Xu Y, Lv L, et al. WT1 recruits TET2 to regulate its target gene expression and suppress leukemia cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2015;57:662–73.

Pronier E, Bowman RL, Ahn J, Glass J, Kandoth C, Merlinsky TR, et al. Genetic and epigenetic evolution as a contributor to WT1-mutant leukemogenesis. Blood. 2018;132:1265–78.

Perry M, Bertoli S, Rocher C, Hayette S, Ducastelle S, Barraco F, et al. FLT3-TKD mutations associated with NPM1 mutations define a favorable-risk group in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018;18:e545–50.

Boddu P, Kantarjian H, Borthakur G, Kadia T, Daver N, Pierce S, et al. Co-occurrence of FLT3-TKD and NPM1 mutations defines a highly favorable prognostic AML group. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1546–50.

Bacher U, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Prognostic relevance of FLT3-TKD mutations in AML: the combination matters—an analysis of 3082 patients. Blood. 2008;111:2527–37.

Simonetti G, Mengucci C, Padella A, Fonzi E, Picone G, Delpino C, et al. Integrated genomic-metabolic classification of acute myeloid leukemia defines a subgroup with NPM1 and cohesin/DNA damage mutations. Leukemia. 2021;35:2813–26.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all institutions and investigators who participated in the CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial and contributed to this study. We thank Dr. Karl-Heinz Holzmann (Genomics Core Facility, Ulm University) for his support with the targeted sequencing analysis. This work was supported in part by Novartis and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 1074 project B3 to KD and LB), a grant by the BMBF (DRAMA 01KT1603 to HD), and by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants U10CA180821 (to the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Operations Center), U10CA180882 (to the Alliance Statistics and Data Management Center), U24CA196171 (to the Alliance NCTN Biorepository and Biospecimen [CDB]), U10CA180861 (ITSC for Leukemia: Novel Molecular Strategies for NCTN: Individualized Therapies).

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NJ and EJ designed study, performed molecular analyses, analyzed data, and wrote the paper. MS, JK, and AB performed statistical analyses and wrote the paper. LB, RAL, TO, SA, TWP, JMB, FRA, BCM, MST, GE, MH, AG, CP, IG, CT, and RMS collected, assembled, analyzed, interpreted data, and reviewed the paper. CDB designed study, collected, assembled, analyzed, and interpreted data. HD and KD designed study, collected, assembled, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MS has a collaboration with Boehringer Ingelheim. LB was on advisory committees for AbbVie, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead, Hexal, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Seattle Genetics, and has received research support from Bayer and Jazz Pharmaceuticals. RAL has acted as a consultant or advisor to Novartis, AbbVie, Amgen, Ariad/Takeda, Astellas, Celgene/BMS, CVS/Caremark, Epizyme, and MorphoSys, and has received clinical research support to his institution from Novartis, Astellas, Celgene, Cellectis, Daiichi Sankyo, Forty Seven, Gilead, and Rafael Pharmaceuticals, and royalties from UpToDate. FRA serves on advisory boards for Adaptive Biotechnology and Jasper Therapeutics. MH received honoraria from Abbvie, Eurocept, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Novartis, Takeda, funding for institution from Astellas, Bayer Pharma AG, BergenBio, Daiichi Sankyo, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and consults Abbvie, Agios, BMS, Daiichi Sankyo, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kura Oncology, Novartis, Pfizer, PinotBio, Roche, Tolremo. AG serves on advisory board for Novartis and received research support from Novartis. IG and CP are employees of Novartis. RMS reports personal fees from AbbVie, Actinium, Agios, Argenx, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Biolinerx, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Elevate, Gemoab, Janssen, Jazz, Macrogenics, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Hoffman LaRoche, Stemline, Syndax, Syntrix, Syos, Takeda, and Trovagene and received research support from AbbVie, Agios, Arog, and Novartis. HD has acted as a consultant or advisor for AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GEMoaB, Gilead, Janssen, Jazz, Novartis, Servier, Syndax and has received institutional research support from AbbVie, Agios, Amgen, Astellas, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Kronos Bio, Novartis. KD was on advisory committees for Novartis, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Daiichi Sankyo. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jahn, N., Jahn, E., Saadati, M. et al. Genomic landscape of patients with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML) treated within the CALGB 10603/RATIFY trial. Leukemia 36, 2218–2227 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01650-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-022-01650-w

This article is cited by

-

Current knowledge about FLT3 gene mutations, exploring the isoforms, and protein importance in AML

Molecular Biology Reports (2024)

-

FLT3 targeting in the modern era: from clonal selection to combination therapies

International Journal of Hematology (2023)

-

Impact of genetic patterns on sorafenib efficacy in patients with FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a multi-center, cohort study

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2023)