Abstract

Summary

This narrative review describes efforts to improve the care and prevention of fragility fractures in New Zealand from 2012 to 2022. This includes development of clinical standards and registries to benchmark provision of care, and public awareness campaigns to promote a life-course approach to bone health.

Purpose

This review describes the development and implementation of a systematic approach to care and prevention for New Zealanders with fragility fractures, and those at high risk of first fracture. Progression of existing initiatives and introduction of new initiatives are proposed for the period 2022 to 2030.

Methods

In 2012, Osteoporosis New Zealand developed and published a strategy with objectives relating to people who sustain hip and other fragility fractures, those at high risk of first fragility fracture or falls and all older people. The strategy also advocated formation of a national fragility fracture alliance to expedite change.

Results

In 2017, a previously informal national alliance was formalised under the Live Stronger for Longer programme, which includes stakeholder organisations from relevant sectors, including government, healthcare professionals, charities and the health system. Outputs of this alliance include development of Australian and New Zealand clinical guidelines, clinical standards and quality indicators and a bi-national registry that underpins efforts to improve hip fracture care. All 22 hospitals in New Zealand that operate on hip fracture patients currently submit data to the registry. An analogous approach is ongoing to improve secondary fracture prevention for people who sustain fragility fractures at other sites through nationwide access to Fracture Liaison Services.

Conclusion

Widespread participation in national registries is enabling benchmarking against clinical standards as a means to improve the care of hip and other fragility fractures in New Zealand. An ongoing quality improvement programme is focused on eliminating unwarranted variation in delivery of secondary fracture prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

The need for a systematic approach to care and prevention of fragility fractures

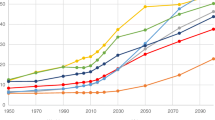

During the twenty-first century, the age structure of the human population will undergo the most significant and rapid change in history. Humankind is en route to a new demographic era, as noted by both the Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) [1] and the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) [2]. The so-called old-age dependency ratio is the ratio of the population aged 65 years or over to the population aged 15–64 years, who are considered to be of working age. In Fig. 1, these ratios are presented as the number of dependents per 100 persons of working age for the world, Asia and New Zealand, an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean with a population of 5.1 million people. The old-age dependency ratio in New Zealand is currently higher than many other countries and will continue to increase for the rest of this century.

Old-age dependency ratios for the world, Asia and New Zealand from 1950 to 2100 [3] (from World Population Prospects: Volume II: Demographic Profiles 2017 Revision. ST/ESA/SER.A/400, by Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, ©2017 United Nations. Reprinted with the permission of the United Nations)

A direct consequence of this demographic shift will be a significant increase in the number of older people who are living with chronic conditions, which will include osteoporosis and associated fragility fractures. In New Zealand, the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC, the Crown entity responsible for injury prevention) [4] estimated that the 155,000 claims made in 2020 for falls and fracture-related injuries among New Zealanders aged 65 years or over cost NZ$195 million (US$140 million, Euro 121 million), representing a 47% increase since 2013 [5]. Furthermore, ACC estimates that the costs of ‘doing nothing’ would more than double to NZ$400 million (US$288 million, Euro 248 million) by 2035.

In 2021, a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study, for the first time, characterised the global, regional and national burden of fractures sustained at all ages in 204 countries and territories for 1990 and 2019 [6]. The GBD Study estimated there were:

-

178 million (95% uncertainty interval [UI], 162–196) new fractures, an increase of 33.4% (95% UI, 30.1–37.0) since 1990.

-

455 million (95% UI, 428–484) prevalent cases of acute or long-term symptoms of a fracture, an increase of 70.1% (95% UI, 67.5–72.5) since 1990.

-

25.8 million (95% UI, 17.8–35.8) years lived with disability (YLDs), an increase of 65.3% (95% UI, 62.4–68.0) since 1990.

In 2019, at the national or territory level, New Zealand was among the top three countries for each of these measures of burden in terms of age-standardised rates. As the majority of fractures occurred among older people, the first of four sets of policy and practice recommendations from the GBD Study authors included:

-

Expand screening and treatment of osteoporosis in older people.

-

Provide educational materials, assistive devices and other products to reduce the risk of falls.

-

Encourage exercise and diet that promotes bone strength throughout the life-course.

The third recommendation stated “… particularly in countries with the highest age-standardised disability burdens due to fractures, such as New Zealand and Slovenia, focusing on evidence-based policies to prevent fractures offers considerable value because fractures contribute so substantially to the overall burden of disability in these countries”.

The purpose of this paper is to describe ongoing efforts in New Zealand to address the challenges identified in the GBD Study. The approach is founded upon collaboration between all relevant stakeholder organisations, including government ministries and organisations, healthcare professional societies, non-governmental organisations and charities and representatives of District Health Boards and Primary Health Organisations. The systematic approach embraces the philosophy advocated by the IOF Capture the Fracture® Programme launched in 2012 [7], and the recommendations made in the Global Call to Action on Fragility Fractures published in 2018 [8], which could be adopted or adapted by colleagues in other countries.

Development of a national systematic approach

In 2012, Osteoporosis New Zealand published BoneCare 2020: A systematic approach to hip fracture care and prevention for New Zealand [9]. At the time of publication, New Zealand lacked a coordinated, nationwide strategy and systems to optimally manage individuals who sustained fragility fractures. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the initial four objectives of BoneCare 2020 were aligned to those advocated in the strategy to reduce the incidence of falls and fractures in England published by the Department of Health in 2009 [10]. Consistent with the approach to develop and maintain bone health throughout the life-course advocated by IOF in 2015 [11], the initial focus of BoneCare 2020 on older people was expanded to include all adults and children with the addition of objectives five and six in Fig. 2.

A systematic approach to fragility fracture care and prevention for New Zealand [9] (reproduced with kind permission of Osteoporosis New Zealand)

As a mechanism for all relevant stakeholder organisations to speak with a unified voice to policymakers, establishment of multisector and multidisciplinary alliances at the national level has been advocated by international organisations, including the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) [12, 13], FFN [14] and IOF [2]. Osteoporosis New Zealand strongly supports this approach and invited all relevant professional organisations, policy groups and private sector partners to join a national fragility fracture alliance to develop and implement this strategy. As described below, an informal alliance of organisations progressed implementation of the objectives proposed in BoneCare 2020 during the period 2012 to 2016. In 2017, the alliance was formalised under the Live Stronger for Longer programme [15], partners and contributors to which include ACC, Ministry of Health, Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand, Osteoporosis New Zealand, Carers New Zealand, Age Concern, St. John Ambulance, Stroke Foundation of New Zealand, District Health Boards, Primary Health Organisations and representatives of healthcare professional organisations.

Summaries of implementation efforts for each of the six objectives follow.

A systematic approach to implementation: Clinical priorities

Objective 1

Improve outcomes and quality of care after hip fractures by delivering Australian and New Zealand professional standards of care monitored by the New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry.

In 2020, in the second edition of a textbook on orthogeriatrics [16], Marsh et al. noted a substantial increase in the cumulative number of citations for keyword ‘orthogeriatrics’ in Google Scholar during the previous decade, from approximately 100 up to year 2010 to almost 3500 up to year 2019. The first publication cited in the PubMed database from an orthogeriatric service in New Zealand was from Christchurch in 1996 [17]. Subsequent publications have described the work of services in Auckland [18, 19], Christchurch [20,21,22] and Dunedin [23].

In September 2011, the Australian and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine published an updated version of their Position Statement on Orthogeriatric Care [24]. A month later, a preliminary meeting of representatives of stakeholder organisations was held in Sydney, Australia, to explore the potential for an Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR). The subsequent development and implementation of the ANZHFR [25] is the subject of a detailed case study that is an appendix to the Hip Fracture Registry Toolbox published in mid-2021 as a collaboration between the Asia Pacific Fragility Fracture Alliance (APFFA) and FFN [26]. Key milestones included:

-

2012: The ANZHFR Steering Group was the recipient of a Bupa Health Foundation Award of AU$477,000 (US$357,750, Euro 310,050) [27] which enabled:

-

Production of the Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care published in 2014 [28].

-

Work towards clinical care standards and quality indicators to enable benchmarking of care.

-

Development of a ‘consumer manifesto’ whereby members of the general public articulated their own views as to what constituted high quality care.

-

Piloting patient level data collection in all States/Territories in Australia.

-

-

2015: The initial development and piloting of data collection for the New Zealand arm of the ANZHFR was supported by grants from Osteoporosis New Zealand and the Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. ACC allocated core funding to support the New Zealand arm of ANZHFR from 2016 to 2018, and thereafter to the present day.

-

2016: Publication of the first Patient Level Audit, combined with the fourth Facility Level Audit [29], which included data from 25 of 121 public hospitals across both countries, with 3519 individual patient records (2925 from 21 hospitals in Australia and 594 from 4 hospitals in New Zealand). Publication of the audits coincided with the launch of the ‘trans-Tasman’ (i.e. Australian and New Zealand) Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard [30], the first joint Australian and New Zealand set of clinical care standards co-produced by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care and the Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand.

-

2020: Comprehensive participation in the Patient Level Audit by all District Health Boards (n = 20) in New Zealand was achieved by September 2020.

-

2021: The ANZHFR Annual Report 2021 [31] included data from 86 hospitals in the sixth Patient Level Audit and all 117 hospitals that were invited to participate in the ninth Facility Level Audit. Based on comparison with discharge coding reported in the National Minimum Data Set, it was estimated that case ascertainment had reached 86% in New Zealand during calendar year 2020, with 3334 records from 22 hospitals. As of June 2021, there were a total of 14,604 records in the New Zealand arm of the ANZHFR since inception.

Facility Level Audits assess and document what services, resources, policies, protocols and practices exist across a health care system. As shown in Fig. 3, a wealth of data has been generated by these audits over the last decade demonstrating where improvement in access to particular services has occurred, and where such improvements are still to be made. This is most notable for access to fracture liaison services (FLS) across both countries, which has almost doubled from 2014 to 2020.

Proportion of Australian and New Zealand Hospitals reporting specific services beyond the acute stay from 2014 to 2020 [31] (reproduced with kind permission of the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry)

The Patient Level Audits document processes and outcomes of care for each hospital participating in the ANZHFR reported for patient presentation to hospital, surgery, the post-operative period of the hospital stay and at 120-day follow-up. The ANZHFR Annual Report 2021 included 52 figures that document various aspects of care provided by participating hospitals on a named basis [31]. As an example, the proportion of patients with a hip fracture who had their preoperative cognitive status assessed is shown in Fig. 4.

Proportion of hip fracture patients who underwent preoperative cognitive assessment during acute admissions to hospitals in Australia and New Zealand during 2020 [31] (reproduced with kind permission of the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry)

The ANZHFR 2021 Annual Report also documented changes over time, or not, for facilities level and patient level indicators relating to the seven quality statements in the bi-national Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard [30]. It should be noted that since 2013 all 22 eligible hospitals in New Zealand have participated in annual facility level audits that document organisational aspects as described for Quality statements 1 and 7 below. The number of eligible hospitals contributing to annual patient level audit reports increased from 4 hospitals in 2016 to all 22 hospitals in 2021, thus the denominators have changed over time for the patient level data reported for Quality statements 2 to 6 below. Findings included:

-

Quality statement 1—Care at presentation: The proportion of hospitals in New Zealand with a hip fracture pathway as a reported element of hip fracture care increased from 70% in 2013 to 95% in 2020.

-

Quality statement 2—Pain management: The proportion of patients in New Zealand who had a documented assessment of pain within 30 min of presentation to the Emergency Department was 50% in 2017 and 62% in 2020.

-

Quality statement 3—Orthogeriatric model of care: The proportion of patients in New Zealand who saw a geriatrician during their acute hospital stay has remained approximately the same since patient level data has been collected, at 79% in 2016 and 82% in 2020.

-

Quality statement 4—Timing of surgery: The proportion of patients in New Zealand who underwent surgery within 48 h of presentation with hip fracture has also remained approximately constant at 86% in 2016 and 83% in 2020.

-

Quality statement 5—Mobilisation and weight bearing: Among patients treated at hospitals with more than 80% follow-up at 120 days (n = 18/22), the proportion returning to pre-fracture mobility at 120 days was 44% in 2016 and 51% in 2020.

-

Quality statement 6—Minimising risk of another fracture: The proportion of patients receiving a bisphosphonate, denosumab or teriparatide remained suboptimal in 2020, at 29% on discharge and 40% at 120 days. However, as is the case for other indicators reported by the ANZHFR, variation between hospitals is substantial, ranging from 2 to 65% of patients leaving hospital on an osteoporosis-specific treatment. The next section on the second objective of BoneCare 2020 describes new approaches to address this issue.

-

Quality statement 7—Transition from hospital care: The proportion of hospitals in New Zealand reporting routine provision of written information on treatment and care after hip fracture was 22% in 2013 and 59% in 2020.

As noted by Currie, well-used continuous feedback “… is continuously and consistently empowering and encourages a strategic approach. And units that make a regular practice of monthly audit meetings to scrutinise their own data can use it … to identify and quantify problems and address them as they emerge, with or without management support: a prompt and flexible ‘fire-fighting’ response that only continuous audit can provide” [32].

Inspired by ‘Hip Fests’ (i.e. Hip Festivals) conducted at the State-level in Australia since 2018, similar Hip Fests were held for multidisciplinary teams in the North and South Islands of New Zealand in 2019, which are available as recordings on the ANZHFR website [33]. The Hip Fests are open to clinicians, support staff, healthcare and hospital executives, and provide a forum for sharing of best practice. In 2020, on account of the COVID-19 pandemic, ANZHFR produced a series of lectures in lieu of in-person meetings that can be viewed on the ANZHFR Training and Education channel on YouTube [34]. In 2021, virtual Hip Fests were held in both countries and—inspired by the Scottish Hip Fracture Audit [35] and the Irish Hip Fracture Database [36]—a ‘Golden Hip Award’ was introduced to celebrate the top performing hospital in hip fracture care for each country. North Shore Hospital in Waitematā District Health Board (DHB) was the recipient of the award for New Zealand. Participation in the ANZHFR led Waitematā DHB to identify the need for an orthogeriatrician to provide comprehensive geriatric assessment and management for hip fracture patients. Success factors include:

-

Attendance of the orthogeriatrician at the acute trauma morning meetings to advocate for hip fracture patients to be prioritised for surgery.

-

Regular multidisciplinary meetings with representatives from the emergency department, anaesthetic department and orthopaedic department to discuss barriers and solutions identified in patient’s journey through the system.

-

Development of a hip fracture care pathway from admission through to rehabilitation tailored specifically for WDHB.

As demonstrated in Table 1, improvements have been made against key performance indicators recorded in the ANZHFR since 2017. Furthermore, total length of stay reduced from 22 days in 2017 [37] to 17 days in 2021 [31].

In 2020, the Christchurch orthogeriatric service compared outcomes for four groups [38]:

-

1.

Publicly funded aged residential care (ARC) residents discharged directly from acute orthopaedics.

-

2.

Non-ARC residents discharged directly from acute orthopaedics.

-

3.

Patients discharged after orthogeriatric rehabilitation.

-

4.

Patients discharged after general geriatric rehabilitation.

Patients admitted for orthogeriatric rehabilitation had shorter length of stay, lower 30-day mortality, were more likely to return home and most likely to be offered osteoporosis treatment (88%).

Objective 2

Respond to the first fracture to prevent the second through universal access to Fracture Liaison Services in every District Health Board in New Zealand.

In October 2012, IOF published the World Osteoporosis Day thematic report on the Capture the Fracture® Programme [7] and the ASBMR Task Force report on secondary fracture prevention was also published [12, 13]. The IOF Capture the Fracture® Programme has since become a major flagship initiative for IOF, noting that “… implementation of coordinated, multi-disciplinary models of care for secondary fracture prevention … is recognized as the single most important step in directly improving patient care and reducing spiralling fracture-related healthcare costs worldwide” [39]. This sentiment was echoed in December 2012 in BoneCare 2020 [9], again in 2015 in the Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society Position Paper on Secondary Fracture Prevention Programs [40], and in 2018 in the Global Call to Action on Fragility Fractures [8], which has since been endorsed by 130 learned societies and other organisations worldwide, including ACC, the Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand and the Ministry of Health.

A brief chronology of the implementation of the FLS model of secondary preventive care in New Zealand follows:

-

2012–2013: A nascent FLS was established in Waitematā DHB at North Shore Hospital in Auckland. Pursuant to interactions between representatives of Osteoporosis New Zealand and the Minister of Health, and senior clinical advisors to the Minister, the Ministry of Health set an expectation that all District Health Boards would implement a FLS during the financial year July 2013 to June 2014 [41], which was continued for the following financial year July 2014 to June 2015 [42].

-

2014: The Ministry of Health collaborated with Osteoporosis New Zealand, the four Regional District Health Board Alliances, and clinical, information technology, service development and management teams from the District Health Boards to share best practices in development of FLS, from the Waitematā FLS in Auckland and extensive experience from overseas. By August 2014, six of the 20 District Health Boards had some form of FLS in place.

-

2015: Osteoporosis New Zealand facilitated a first meeting between FLS Coordinators and representatives of ACC and the Ministry of Health. A parallel educational component of this meeting catalysed the formation of the Fracture Liaison Network New Zealand, comprised of all FLS Coordinators in the country, which has since provided a mechanism to expedite sharing of best practice between FLS.

-

2016: The first peer-reviewed publication from a New Zealand FLS was published to describe the establishment and initial operations of the Waitematā FLS [43]. Osteoporosis New Zealand published a broadly endorsed first edition of Clinical Standards for FLS in New Zealand [44]. ACC made an investment of NZ$30.5 million (US$22.0 million, Euro 18.9 million) to support the nationwide implementation of the following initiatives [45]:

-

A FLS in every District Health Board

-

In-home and community-based strength and balance programmes

-

Assessment and management of visual acuity and environmental hazards in the home

-

Medication review for people taking multiple medicines

-

Vitamin D prescribing in Aged Residential Care

-

Integrated services across primary and secondary care (including supported hospital discharge) to provide seamless pathways in the falls and fracture system

-

-

2019: Some form of FLS was in place in all District Health Boards by December 2019. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in the scope and organisation of these services. Furthermore, when COVID-19 reached New Zealand in early 2020, some FLS Coordinators were redeployed due to the pandemic.

-

2020: In November 2020, ACC announced a second major investment in the Live Stronger for Longer programme that was intended to [5]:

-

Sustain delivery of approved Community-based Strength and Balance classes

-

Support District Health Boards to sustain delivery of their respective In-Home Strength and Balance programmes

-

Establish and embed a best-practice FLS within each District Health Board region

-

Explore, qualify and leverage Digital Strength and Balance opportunities

-

Sustain the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry

-

Sustain the use of the Live Stronger for Longer website and Health Sector Information Dashboards

-

Increase awareness of bone health (in close collaboration with Osteoporosis New Zealand and other key stakeholders)

-

Explore development of an Australian and New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry to enable benchmarking of the performance of FLS

The announcement of the second ACC investment clearly articulated that from July 2021, ACC funding would be focused on supporting District Health Boards and/or Primary Health Organisations to develop and embed a FLS accredited by the IOF Capture the Fracture® Best Practice Framework [46] that will be sustainable by the health sector without the need for ongoing ACC funding after June 2024. To the authors’ knowledge, this is one of just two examples of a government agency specifically linking funding of FLS in the public sector to IOF Capture the Fracture® accreditation. A similar approach has been advocated by the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand [47].

-

-

2021–2022: In December 2020, Osteoporosis New Zealand and ACC devised a national quality improvement programme for FLS in New Zealand comprised of the following key elements, that was implemented during 2021 and 2022:

-

Workforce development:

-

Undertook a national survey to establish baseline levels of capability and performance of FLS, which facilitated development and delivery of workshops to engage multidisciplinary teams in each District Health Board region to ensure a broad team was engaged rather than FLS Coordinators operating in isolation.

-

Provided support and mentoring for each service through Osteoporosis New Zealand and the Fracture Liaison Network New Zealand to enable FLS to deliver a world-class service in accordance with the IOF Capture the Fracture® Best Practice Framework [46, 48].

-

-

Nationwide quality improvement:

-

Development of a broadly endorsed second edition of the Clinical Standards for FLS in New Zealand [49] with patient level key performance indicators (KPIs) that can be measured. The KPIs were informed by the KPI set published in 2020 jointly by IOF, FFN and the Bone Health and Osteoporosis Foundation of the United States of America (formerly the National Osteoporosis Foundation) [50].

-

Developed the New Zealand arm [51] of a new Australian and New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry [51, 52] that enables FLS teams, in real time, to benchmark the care they provide, identify variation in service delivery and continuously improve secondary fragility fracture prevention. As of June 2022, local site approvals for participation have been granted for 13 FLS sites to enable entry of patient-level data and 12 FLS are participating in the registry.

-

-

Readiness for health care reform:

-

Established a national systems approach in advance of the largest health reform ever undertaken in New Zealand, which is set to commence implementation in 2022 [53].

-

Evidence-based and standardised contracting for FLS between ACC and District Health Boards effectively managed at a regional level by ACC Regional Injury Prevention Partners to ensure equitable service provision for all New Zealanders.

-

-

On the IOF Capture the Fracture® Map of Best Practice [54], as of June 2022, 737 FLS from 50 countries featured, including nine from New Zealand. This includes four FLS that had achieved Gold Star recognition, four with Silver Stars and one with a Bronze Star. Collectively, these nine FLS deliver secondary fracture prevention for 58% of the population of New Zealand. The overarching objective of the current FLS quality improvement programme in New Zealand is for there to be near universal access (i.e. for at least 90% of regions) to IOF-accredited FLS by mid-2024, with the majority achieving Gold Star recognition.

Objective 3

General practitioners to stratify fracture risk within their practice population using fracture risk assessment tools supported by local access to axial bone densitometry.

In 2017, Osteoporosis New Zealand convened an Expert Panel to develop practical guidance for healthcare professionals relating to individuals at high risk of sustaining fragility fractures. The Guidance on the Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis in New Zealand [55] made recommendations relating to identification, diagnosis and treatment for people who had sustained prior fragility fractures and those at high risk of sustaining a first fragility fracture. In 2022, Osteoporosis New Zealand plans to update this guidance, considering the approach to updating clinical guidance advocated by the Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis [56]. Furthermore, a collaborative approach with the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners is an aspiration, akin to that jointly developed by the Royal Osteoporosis Society and the Royal College of General Practitioners in the UK [57]. A key consideration will be to develop information technology solutions to enable busy general practitioners to implement the guidance for their practice population, cognisant of the many competing demands upon their time.

A systematic approach to implementation: Public awareness

Objective 4

Consistent delivery of public health messages—to adults with healthy bones aged 65 years and over—on preserving physical activity, healthy lifestyles and reducing environmental hazards.

Objective 5

Consistent delivery of public health messages—to adults with healthy bones aged 19–64 years—to exercise regularly, eat well to maintain a healthy body weight and create healthy lifestyle habits.

In 2016, the Ministry of Health published the Healthy Ageing Strategy [58] for New Zealand which is aligned to the World Health Organization global strategy [59]. The Healthy Ageing Strategy’s key strategic themes are:

-

1.

Prevention, healthy ageing and resilience throughout people’s older years

-

2.

Living well with long-term health conditions

-

3.

Improving rehabilitation and recovery from acute episodes

-

4.

Better support for older people with high and complex needs

-

5.

Respectful end-of-life care

The Ministry of Health noted that the Live Stronger for Longer programme was a key achievement during the first two years of implementation of the strategy [60].

In 2017, Osteoporosis New Zealand first conceptualised a new approach to consumer engagement aligned to the first theme of the Healthy Ageing Strategy above. The previous year, colleagues in Osteoporosis Australia had launched the Know your Bones™ online consumer-friendly, fracture risk self-assessment tool [61] which had been developed collaboratively with the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney, Australia. In 2019, Osteoporosis New Zealand signed an agreement to licence the Know your Bones™ tool and develop a version of the tool for the New Zealand context. Aligned to the life-course approach to healthy ageing advocated by the Ministry of Health, Osteoporosis New Zealand developed a consumer-facing “brand”—Bone Health New Zealand—with the intention of stimulating a new national conversation on the need for a pro-active approach to maintaining a healthy skeleton. Bone Health New Zealand addresses the common misperception that osteoporosis only affects elderly women and, therefore, is not relevant to other groups, including the initial target audience of women aged 45 to 60 years.

In early 2020, a targeted digital campaign launched Bone Health New Zealand. The initial objective was for 3000 women to complete the Know your Bones™ assessment and, if the report deemed them to be at risk of sustaining a fragility fracture or a fall, to discuss their personalised report with their general practitioner regarding management and risk mitigation options. During the first 3 weeks of the campaign, approximately 500 people completed the Know your Bones™ assessment, which exceeded industry benchmarks. On March 25, 2021, on account of the COVID-19 outbreak, New Zealand went into Alert Level 4, putting the entire country into lockdown. This interrupted plans to secure additional funding for the campaign.

In June 2020, a grant from Mediaworks NZ—a television, radio and interactive media company—provided an opportunity to promote the Bone Health New Zealand campaign with a television commercial that would air for 2 weeks on NZ TV3. A 30-s commercial was produced, which can be viewed on YouTube at https://youtu.be/bBQd1WHHiJo [62]. The commercial encouraged viewers to visit www.bones.org.nz to complete the Know your Bones™ assessment. As illustrated in Fig. 5, a still image of the commercial was also displayed on three digital billboards in prominent locations in Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city. During the 2-week period that the commercial aired, 5000 people completed the Know your Bones™ assessment, representing 1 in 1000 New Zealanders. This significantly exceeded expectations and illustrates that a very simple message, combined with a clear call to action, can engage members of the public, at scale.

Bone Health New Zealand Know your Bones™ television commercial [62] (reproduced with kind permission of Osteoporosis New Zealand)

Osteoporosis New Zealand is currently working to secure funding to broaden the Bone Health New Zealand campaign to target all New Zealanders aged 50 years or over who have sustained a fragility fracture. In due course, and with adequate resource, the intention would be to expand this to the entire population of 1.8 million people aged 50 years or over in New Zealand.

There remains much work to be done to address objectives 4 and 5 of BoneCare 2020 [9], which will be considered in a new strategy for the current decade, BoneCare 2030, outlined below.

Objective 6

Consistent delivery of public health messages—to children with healthy bones aged up to 18 years—on accrual of peak bone mass through a well-balanced diet and regular exercise which promotes bone development.

In late 2017, representatives of Osteoporosis New Zealand met with the leadership of a prominent high school in Auckland to explore the potential for incorporation of bone health awareness into the curricula for science, health and physical education. This was followed by an introductory lecture and discussion session with school staff and alumnae. As the least progressed of the BoneCare 2020 objectives, attention will be given in BoneCare 2030 to strategies to improve awareness among children and stimulation of intergenerational conversations within families.

The next decade: BoneCare 2030

In December 2020, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2021–2030 the Decade of Healthy Ageing [63]. During the previous decade, BoneCare 2020 served as a stimulus to promote a systematic approach to bone health in New Zealand which successfully engaged a broad array of stakeholders to work towards mutually agreed goals. These two factors provide the rationale for development of a strategy for bone health in New Zealand for the current decade. Osteoporosis New Zealand is committed to collaboratively develop BoneCare 2030 with all organisations that have contributed to date and to expand the stakeholder group to strengthen the approach for aspects where limited progress has been made, including the consideration of equitable outcomes being actively designed for and monitored.

According to the six objectives proposed in BoneCare 2020, achievements by 2030 should include:

-

Objective 1: The care of people who sustain hip fractures to be documented in the New Zealand arm of the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry [25], and, from 2023 to 2030, all patients to receive best practice as described by the Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard [30].

-

Objective 2: Universal access to IOF-accredited Gold Star FLS to be available from 2025, and for the care of individuals who sustain fragility fractures at any relevant skeletal site to be benchmarked against the second edition of the Clinical Standards for FLS in New Zealand [49] in the New Zealand arm of the Australian and New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry [51].

-

Objective 3: A collaboration led by the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners, Osteoporosis New Zealand, Ministry of Health, Health NZ, Māori Health Authority and ACC to ensure reliable identification, investigation and interventions for all New Zealanders who are at high risk of sustaining fragility fractures, underpinned by state-of-the-art information technology solutions and regularly updated national clinical guidance.

-

Objective 4: New Zealanders aged 65 years or over to complete the Know your Bones™ online self-assessment and discuss their personalised report with their general practitioner. Osteoporosis New Zealand, ACC and the Ministry of Health to collaborate to develop awareness campaigns relating to preserving physical activity, healthy lifestyles and reducing environmental hazards.

-

Objective 5: New Zealanders aged 50–64 years to complete the Know your Bones™ online self-assessment and discuss their personalised report with their general practitioner. Osteoporosis New Zealand to collaborate with all relevant stakeholder organisations to develop awareness campaigns relating to regular exercise, nutrition to maintain a healthy body weight and creating healthy lifestyle habits.

-

Objective 6: Osteoporosis New Zealand to collaborate with the Ministry of Education, academic educationalists and teachers, and their professional organisations to incorporate content relating to bone health into the school curricula for science, health and physical education.

The 2015 IOF World Osteoporosis Day thematic report summarised associations between inadequate maternal nutrition and bone development of offspring [11, 64]. Consideration should be given to an additional objective relating to maternal diet and bone health.

Conclusions

A significant proportion of the systematic approach to care and prevention of fragility fractures proposed in Osteoporosis New Zealand’s BoneCare 2020 has been developed and implemented during the period 2012 to 2022. Most progress has been made in relation to the care of individuals who have sustained hip or other fragility fractures, supported by production of clinical standards and registries to benchmark provision of care. Formation of a national alliance of stakeholder organisations from different sectors, including government, medical charities and not-for-profit organisations focused on older people, healthcare professional organisations and the health sector has facilitated much of the progress made to date. Creation of a consumer-facing, not-for-profit “brand” that emphasises bone health rather than osteoporosis, per se, shows early promise in the promotion of greater public awareness. As New Zealand begins to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, a determined effort is required to capitalise on the gains made during the 2010s to deliver optimal outcomes for individuals who sustain fragility fractures in the 2020s, and to reduce the burden of new fragility fractures on older New Zealanders, their families, the health system and the national economy.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Mitchell PJ, Magaziner J, Costa M, Seymour H, Marsh D, Falaschi P, Beaupre L, Tabu I, Eleuteri S, Close J, Agnusdei D, Speerin R, Kristensen MT, Lord S, Rizkallah M, Caeiro JR, Yang M (2020) FFN Clinical Toolkit. 1st Edition. Fragility Fracture Network. Zurich. https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Cooper C and Ferrari S, on behalf of the IOF Board and Executive Committee (Reginster JY, Chair of Committee of National Societies; Dawson-Hughes B, General Secretary; Rizzoli R, Treasurer; Kanis J, Honorary President; Halbout P, CEO) (2019) IOF Compendium of Osteoporosis. 2nd Edition. Writer: Mitchell P. Reviewers: Harvey N and Dennison E. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Nyons. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/educational-hub/files/iof-compendium-osteoporosis-2nd-edition. Accessed 20 July 2022

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division (2017) World Population Prospects: Volume II: Demographic Profiles 2017 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/400). New York

Accident Compensation Corporation (2021) Accident Compensation Corporation website. https://www.acc.co.nz/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Accident Compensation Corporation (2020) Live Stronger for Longer Board Paper October 2020. Wellington

Wu A-M, GBD (2019) Fracture Collaborators (2021) Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev 2:e580–e592

Akesson K, Mitchell PJ (2012) Capture the fracture: a global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. In: Stenmark J, Misteli L (eds) World Osteoporosis Day Thematic Report. International Osteoporosis Foundation, Nyon

Dreinhofer KE, Mitchell PJ, Begue T et al (2018) A global call to action to improve the care of people with fragility fractures. Injury 49:1393–1397

Osteoporosis New Zealand (2012). BoneCare 2020: A systematic approach to hip fracture care and prevention. Osteoporosis New Zealand. Wellington. https://osteoporosis.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/Bone-Care-2020-web.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022

Department of Health (2009) Falls and fractures: effective interventions in health and social care. In Department of Health (ed)

Mitchell PJ, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B, Gordon CM, Rizzoli R (2015) Life-course approach to nutrition. Osteoporos Int 26:2723–2742

Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R et al (2012) Making the first fracture the last fracture: ASBMR task force report on secondary fracture prevention. J Bone Miner Res 27:2039–2046

Eisman JA, Bogoch ER, Dell R, et al. (2012) Appendix A to ‘making the first fracture the last fracture’: ASBMR Task Force Report on Secondary Fracture Prevention. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jbmr.1698/suppinfo. Accessed 20 July 2022

Marsh D, Mitchell PJ (2019) Guide to formation of national Fragility Fracture Networks. Fragility Fracture Network, Zurich

Accident Compensation Corporation, Ministry of Health, Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand, New Zealand Government (2022) Live stronger for longer: prevent falls and fractures website. http://livestronger.org.nz/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, Falaschi P, Beaupre L, Magaziner J, Seymour H, Costa ML (2020) The multidisciplinary approach to fragility fractures around the world: An overview. In: Falaschi P and Marsh D (eds) Orthogeriatrics: The management of older patients with fragility fractures. 2nd Edition. Springer, Cham, pp 3–18. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-48126-1_1. Accessed 20 July 2022

Elliot JR, Wilkinson TJ, Hanger HC, Gilchrist NL, Sainsbury R, Shamy S, Rothwell A (1996) The added effectiveness of early geriatrician involvement on acute orthopaedic wards to orthogeriatric rehabilitation. N Z Med J 109:72–73

Tha HS, Armstrong D, Broad J, Paul S, Wood P (2009) Hip fracture in Auckland: contrasting models of care in two major hospitals. Intern Med J 39:89–94

Fergus L, Cutfield G, Harris R (2011) Auckland City Hospital’s ortho-geriatric service: an audit of patients aged over 65 with fractured neck of femur. N Z Med J 124:40–54

Sidwell AI, Wilkinson TJ, Hanger HC (2004) Secondary prevention of fractures in older people: evaluation of a protocol for the investigation and treatment of osteoporosis. Intern Med J 34:129–132

Thwaites JH, Mann F, Gilchrist N, Frampton C, Rothwell A, Sainsbury R (2005) Shared care between geriatricians and orthopaedic surgeons as a model of care for older patients with hip fractures. N Z Med J 118:U1438

Gilchrist N, Dalzell K, Pearson S et al (2017) Enhanced hip fracture management: use of statistical methods and dataset to evaluate a fractured neck of femur fast track pathway-pilot study. N Z Med J 130:91–101

Teo SP, Mador J (2012) Orthogeriatrics service for hip fracture patients in Dunedin Hospital: achieving standards of hip fracture care. J Clin Gerontol Geriatr 3:62–67

Mak J, Wong E, Cameron I (2011) Australian and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine. Position statement--orthogeriatric care. Australas J Ageing 30:162–169

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (2022) Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry website. http://www.anzhfr.org/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Close JCT, Seymour H, Mitchell PJ, et al. (2021) Hip Fracture Registry Toolbox: a collaboration between the APFFA Hip Fracture Registry Working Group and the FFN Hip Fracture Audit Special Interest Group. Asia Pacific Orthopaedic Association, Kuala Lumpur

Bupa Health Foundation (2021) Bupa Health Foundation: About us. https://www.bupa.com.au/about-us/bupa-health-foundation. Accessed 20 July 2022

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (ANZHFR) Steering Group (2014) Australian and New Zealand Guideline for Hip Fracture Care: improving outcomes in hip fracture management of adults. Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry Steering Group, Sydney. https://anzhfr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1164/2021/12/ANZ-Guideline-for-Hip-Fracture-Care.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (2016) Annual Report 2016. Sydney

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, Health Quality & Safety Commission New Zealand (2016) Hip Fracture Care Clinical Care Standard. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/clinical-care-standards/hip-fracture-care-clinical-care-standard. Accessed 20 July 2022

ANZHFR Annual Report of Hip Fracture Care (2021) Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry, Sydney. https://anzhfr.org/registry-reports/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Currie C (2018) Hip fracture audit: creating a ‘critical mass of expertise and enthusiasm for hip fracture care’? Injury 49:1418–1423

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (2021) Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry website: Health Professionals. https://anzhfr.org/healthprofessionals/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry (2022) ANZHFR Training and Education. https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpp4eyskmQL3ZImxnCAKSUg. Accessed 20 July 2022

NHS National Services Scotland (2022) The Scottish Hip Fracture Audit website. https://www.shfa.scot.nhs.uk. Accessed 20 July 2022

National Office of Clinical Audit (2022) Irish Hip Fracture Database (IHFD) website. https://www.noca.ie/audits/irish-hip-fracture-database. Accessed 20 July 2022

ANZHFR Bi-National Annual Report for Hip Fracture Care (2017). Australian and New Zealand Hip Fracture Registry, Sydney. https://anzhfr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1164/2021/12/ANZHFR-Annual-Report-2017.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022

Warhurst S, Labbe-Hubbard S, Yi M, Vella-Brincat J, Sammon T, Webb J, McCullough C, Hooper G, Gilchrist N (2020) Patient characteristics, treatment outcomes and rehabilitation practices for patients admitted with hip fractures using multiple data set analysis. N Z Med J 133:31–44

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2022) Capture the Fracture® Programme website. https://www.capturethefracture.org/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Mitchell PJ, Ganda K, Seibel MJ (2015). Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society Position Paper on Secondary Fracture Prevention Programs: A Call to Action. Australian and New Zealand Bone and Mineral Society, Sydney. https://www.anzbms.org.au/downloads/ANZBMSPositionPaperonSecondaryFracturePreventionApril2015.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022

Ministry of Health (2012). 2013/14 Toolkit Annual Plan with Statement of Intent. Ministry of Health. Wellington. No longer available online

Ministry of Health (2014). 2014/15 ANNUAL PLAN Guidelines (Including Planning Priorities) WITH STATEMENT OF INTENT and STATEMENT OF PERFORMANCE EXPECTATIONS. Ministry of Health. Wellington. https://nsfl.health.govt.nz/dhb-planning-package/previous-planning-packages/201415-planning-package/planning-guidelines-201415-0. Accessed 20 July 2022

Kim D, Mackenzie D, Cutfield R (2016) Implementation of fracture liaison service in a New Zealand public hospital: Waitemata district health board experience. N Z Med J 129:50–55

Osteoporosis New Zealand (2016) Clinical standards for fracture liaison services in New Zealand. 1st Edition. Osteoporosis New Zealand. Wellington

New Zealand Government (2016) ACC invests $30m to reduce falls and fractures for older New Zealanders. https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/acc-invests-30m-reduce-falls-and-fractures-older-new-zealanders. Accessed 20 July 2022

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2022) IOF Capture the Fracture®: best practice framework. https://www.capturethefracture.org/best-practice-framework-questionnaire. Accessed 20 July 2022

Strategy and Planning Division, Office of the Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Public Health (2018) Twenty-year national strategic plan for public hHealth (2017-2036) - First Revision 2018. In Strategy and Planning Division, Ministry of Public Health. Bangkok

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD, Kyer C, Cooper C, Group IOFFW (2013) Capture the Fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24:2135-2152

Fergusson K, Gill C, Harris R, Kim D, Mackenzie D., Mitchell PJ, Ward N (2021) Clinical standards for fracture liaison services in New Zealand 2nd Edition. Osteoporosis New Zealand, Wellington

Javaid MK, Sami A, Lems W et al (2020) A patient-level key performance indicator set to measure the effectiveness of fracture liaison services and guide quality improvement: a position paper of the IOF Capture the Fracture Working Group, National Osteoporosis Foundation and Fragility Fracture Network. Osteoporos Int 31:1193–1204

Australian and New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry Steering Group (2022) New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry website. https://fragilityfracture.co.nz/. Accessed 26 May 2022

Australian and New Zealand Fragility Fracture Registry Steering Group (2022) Australian Fragility Fracture Registry website. https://fragilityfracture.com.au/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Department of The Prime Minister and Cabinet (2021) The new health system. https://dpmc.govt.nz/our-business-units/transition-unit/response-health-and-disability-system-review/information. Accessed 20 July 2022

International Osteoporosis Foundation (2022) IOF Capture the Fracture®: Map of Best Practice https://www.capturethefracture.org/map-of-best-practice. Accessed 20 July 2022

Gilchrist N, Reid IR, Sankaran S, Kim D, Drewry A, Toop L, McClure F (2017) Guidance on the Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis in New Zealand. Osteoporosis New Zealand. Wellington. https://osteoporosis.org.nz/resources/health-professionals/clinical-guidance/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Chandran M, Mitchell PJ, Amphansap T et al (2021) Development of the Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO) Framework: clinical standards of care for the screening, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis in the Asia-Pacific region. Osteoporos Int 32:1249–1275

Royal Osteoporosis Society (2022) Osteoporosis resources for primary care. https://theros.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/courses-and-cpd/osteoporosis-resources-for-primary-care/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Associate Minister of Health (2016) Healthy Ageing Strategy. Ministry of Health. Wellington. https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/healthy-ageing-strategy. Accessed 20 July 2022

World Health Organization (2017) Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. Geneva

Ministry of Health (2021) Healthy Ageing Strategy: update. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/life-stages/health-older-people/healthy-ageing-strategy-update. Accessed 20 July 2022

Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Healthy Bones Australia (2022). Know your bones bone health assessment tool. https://www.knowyourbones.org.au/. Accessed 20 July 2022

Bone Health New Zealand (2020) Bone Health New Zealand Know your Bones™ TV Commercial - https://youtu.be/bBQd1WHHiJo. Wellington

World Health Organization (2020) The decade of healthy ageing: a new UN-wide initiative. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-12-2020-decade-of-healthy-ageing-a-new-un-wide-initiative. Accessed 20 July 2022

Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B, Gordon CM, Rizzoli R (2015) Healthy nutrition, healthy bones: How nutritional factors affect musculoskeletal health throughout life. Writer: Mitchell PJ. Editors: Jagait CK and Mistelli L. Reviewers: Edwards M, Harvey NC, Pierroz D. International Osteoporosis Foundation. Nyons. https://www.osteoporosis.foundation/sites/iofbonehealth/files/2019-03/2015_HealthyNutritionHealthyBones_ThematicReport_English.pdf. Accessed 20 July 2022

Acknowledgements

Osteoporosis New Zealand would like to thank the numerous healthcare professionals and colleagues from the government, not-for-profit and healthcare administration sectors in New Zealand, Australia and further afield who have contributed to this body of work during the last decade. In particular, we thank Osteoporosis New Zealand’s advisors, Dr. Michael Nowitz, Dr. Susannah O’Sullivan, Distinguished Professor Ian Reid CNZM and Dr. Jacob Munro, and Dr. Hannah Seymour (President, Fragility Fracture Network), for their encouragement and support. Osteoporosis New Zealand would also like to acknowledge the support of ACC, which enabled licencing of Know your Bones™ from Osteoporosis Australia (which rebranded as Healthy Bones Australia during 2021) and development of the national quality improvement programme for Fracture Liaison Services. We also thank Mediaworks NZ for the grant to air the Bone Health New Zealand TV commercial. Furthermore, very generous pro-bono support from Osteoporosis New Zealand’s agency Deep Ltd., in combination with colleagues at The Rig and Factory Studios, made it possible to produce the television commercial at a fraction of standard costs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

Christine Ellen Gill is the Executive Director of Osteoporosis New Zealand and has no disclosures relating to this work. Adjunct Associate Professor Paul James Mitchell has undertaken consultancy for governments, national and international osteoporosis societies, healthcare professional organisations and private sector companies relating to systematic approaches to fragility fracture care and prevention since 2005. Jan Clark reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Jillian Cornish reports no disclosures relating to this work. Peter Fergusson reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Nigel Gilchrist reports no disclosures relating to this work. Lynne Hayman reports no disclosures relating to this work. Sue Hornblow reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. David Kim reports no disclosures relating to this work. Denise Mackenzie reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Stella Milsom reports no disclosures relating to this work. Adrienne von Tunzelmann reports no disclosures relating to this work. Elizabeth Binns reports no disclosures relating to this work. Kim Fergusson reports no disclosures relating to this work. Stewart Fleming reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Sarah Hurring reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Rebbecca Lilley reports no disclosures relating to this work. Caroline Miller reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Pierre Navarre reports consultancy and payment for development of educational presentations from DePuy Synthes and travel/accommodations/meeting expenses from Stryker, both unrelated to this publication. Andrea Pettett is Chief Executive Officer of the New Zealand Orthopaedic Association and reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Shankar Sankaran reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Min Yee Seow reports no disclosures relating to this work. Jenny Sincock reports no disclosures relating to this work. Nicola Ward reports no disclosures relating to this work. Mr. Mark Wright, FRACS, Orthopaedic Surgeon, reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Jacqueline Clare Therese Close reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Ian Andrew Harris reports no disclosures relating to this work. Elizabeth Armstrong is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Programme (RTP) Scholarship and reports no disclosures relating to this work. Jamie Hallen reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Joanna Hikaka reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Ngaire Kerse reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Andrea Vujnovich reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Kirtan Ganda reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Markus Joachim Seibel reports no disclosures relating to this work. Thomas Jackson reports no disclosures relating to this work. Paul Kennedy reports no disclosures relating to this work. Kirsten Malpas reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Leona Dann reports no disclosures relating to this work. Carl Shuker reports no disclosures relating to this work. Colleen Dunne reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Philip Wood reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Jay Magaziner reports membership of the Own the Bone® Multidisciplinary Advisory Board of the American Orthopedic Association and membership of the Board of the Fragility Fracture Network. Professor David Marsh reports no disclosures relating to this work. Associate Professor Irewin Tabu reports no disclosures relating to this work. Professor Cyrus Cooper has received consulting fees and honoraria from Amgen, Danone, Eli Lilly, GSK, Medtronic, Merck, Nestle, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Shire, Takeda and UCB. Dr. Philippe Halbout is the Chief Executive Officer of the International Osteoporosis Foundation and has no disclosures relating to this work. Associate Professor Muhammad Kassim Javaid reports in the last three years receiving honoraria, unrestricted research grants, travel and/or subsistence expenses from Amgen, Consilient Health, Kyowa Kirin Hakin, UCB, Besin Healthcare and Sanofi. Professor Kristina Åkesson has undertaken consultancy for government related agencies, international and national osteoporosis societies and private sector companies related to osteoporosis and fracture prevention during the past 5 years. Anastasia Soulié Mlotek reports no disclosures relating to this work. Eric Brûlé-Champagne reports no disclosures relating to this work. Dr. Roger Harris reports no disclosures relating to this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christine Ellen Gill and Paul James Mitchell are joint first authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gill, C.E., Mitchell, P.J., Clark, J. et al. Experience of a systematic approach to care and prevention of fragility fractures in New Zealand. Arch Osteoporos 17, 108 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01138-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-022-01138-1