Abstract

In this review, we introduce the progress in the growth of large-aperture DKDP crystals and some aspects of crystal quality including determination of deuterium content, homogeneity of deuterium distribution, residual strains, nonlinear absorption, and laser-induced damage resistance for its application in high power laser system. Large-aperture high-quality DKDP crystal with deuteration level of 70% has been successfully grown by the traditional method, which can fabricate the large single-crystal optics with the size exceeding 400 mm. Neutron diffraction technique is an efficient method to research the deuterium content and 3D residual strains in single crystals. More efforts have been paid in the processes of purity of raw materials, continuous filtration technology, thermal annealing and laser conditioning for increasing the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) and these processes enable the currently grown crystals to meet the specifications of the laser system for inertial confinement fusion (ICF), although the laser damage mechanism and laser conditioning mechanism are still not well understood. The advancements on growth of large-aperture high-quality DKDP crystal would support the development of ICF in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inertial confinement fusion has attracted the worldwide attention as one of the most promising means to obtain clean energy in the future, which has practical application prospects in solving the problem of energy shortage. In 2021, the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) has made a major step forward, which has finally achieved 70% conversion efficiency, nearly reaching ignition1. NIF’s success gives relevant researchers more encouragement. In the past, the research on the growth and performance of large crystal optics has been one of the challenges for the successful construction and operation of NIF2,3,4,5. Large-aperture potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) and its deuterated analog DKDP are applied as electro-optic switches and frequency conversion crystals in ICF, which are attributed to their excellent performance including wide transmittance, high laser damage threshold, large nonlinear optical coefficient, the feature of growing to large sizes and good processability2,3,4,6. In contrast with KDP crystal, DKDP crystal is commonly used for third harmonic generation (THG) due to its weak transverse stimulated Raman scattering (TSRS), which can efficiently reduce the probability of crystal damage in high power laser systems7,8.

So far, laser-induced damage (LID) is still a challenging problem for THG DKDP crystals in the development of high power laser systems, which severely restricts the energy fluence of the output laser and the useful life of crystals. Laser-induced damage of crystal is a rather complex process, which is determined by laser parameters and crystal performance. The effect of laser parameters on LID has been widely investigated including pulse duration, size of the beam spot, laser wavelength9,10,11,12. From the perspective of the material, LID is related to intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic processes include linear absorption, nonlinear effects such as self-focusing, stimulated scattering, collisional (electron avalanche), and multiphoton absorption13,14,15, while extrinsic mechanism could be thermal effects caused by microstructural defects and absorbing inclusions in the materials13,16,17. The understanding of laser-induced damage in DKDP crystal helps to improve the crystal quality in the processes of growth and fabrication, which have been proved by the improvement on laser-induced damage thresholds (LIDT) over the past years. However, the mechanism of LID for THG DKDP crystals is not entirely understood yet and the LIDT of DKDP crystals should be further improved with the development of high power laser systems.

In this review, we present the progress of our research on the growth of large-aperture DKDP crystals and some aspects of crystal properties related to its application in high-power laser systems during the past ten years. These works include determination of deuterium content, homogeneity of deuterium distribution, three-dimensional (3D) residual strains, nonlinear absorption, and laser-induced damage resistance. We hope these data can be used for further improvement of the quality of the large-aperture DKDP crystals to meet the stringent requirements of the ICF project. Finally, we propose several application prospects for the DKDP crystals.

Crystal growth

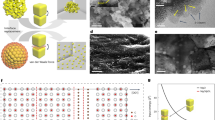

KDP type crystals are usually grown by the aqueous solution method, which mainly includes traditional temperature-reduction method2, solution circulating method18, rapid growth method19. The traditional temperature-reduction method has been widely used to grow large KDP/DKDP crystals, which requires a long growth period of more than two years with a slow growth rate (1–2 mm day−1). This will bring high risk and high cost to large-size crystal growth. However, it is likely to obtain high-quality large-size crystals by the traditional method, which can meet the more stringent requirements of quality and size for nonlinear optical crystals, especially for the third harmonic generation (THG) crystal with further development of the ICF engineering. The optimal growth process is determined by studying the DKDP crystal properties under different growth conditions including raw material, growth method, seed orientation, deuterium content20,21,22,23. Then large DKDP crystal has been successfully grown by traditional method on these bases (Fig. 1), which can fabricate the THG single-crystal optics with the size exceeding 400 mm.

Rapid growth technology has become a hot research topic since the 1990s, which can greatly increase the crystal growth rate (up to 50 mm day−1)24. Compared to the traditional method, the rapid growth method using a point seed can greatly reduce the volume of regenerated seed caps (the opaque region on the seed crystal) and highly improve the crystal utilization rate. The key problem of realizing the rapid rate of crystal growth is the stability and high supersaturation of an aqueous solution. If supersaturation is not properly controlled, the crystallization will occur not only on the crystal surfaces but also on the invisible small crystal nucleus in the solution, which will cause an undesirable spontaneous crystal in the crystallizer and then lead to the failure of rapid growth for large crystals. Nowadays, rapid growth technology has been successfully developed to grow large-aperture high-quality KDP crystals which can meet the requirements for the fabrication of the optics needed for the ICF24,25,26,27,28,29.

At the same time, the point-seed rapid growth technology has been used to grow DKDP crystals. In 1999, N. Zaitseva et al. designed a continuous filtration system for rapid crystal growth which was used to obtain KDP and DKDP crystals with sizes up to 55 cm30. Zhang et al. successfully used point-seed rapid growth technology to grow DKDP crystals with a deuterium content of 98%31,32. In 2019, Cai et al. reported that a highly deuterated DKDP crystal with sizes up to 318 mm × 312 mm × 265 mm was grown by the rapid-growth method33. This demonstrates that growth by the rapid growth method not only shortens the growth period but also avoids the disturbance of monoclinic crystals, especially for the growth of highly deuterated DKDP crystals. However, the pyramid-prism interfaces in the rapidly grown crystals not only decrease the optical properties of crystals but also lead to obvious phase jump, which will cause the intensity modulation of the propagation beam, especially for the third harmonic beam modulation34,35,36,37,38. Researchers have changed the initial seed orientation under the rapid growth conditions to achieve a high yield of THG optics and eliminate the pyramid-prism interfaces4,39,40,41.

For tripler DKDP crystals grown by rapid-growth technology, although successfully producing the large-size optics meeting NIF requirements at LLNL, the material quality did not completely meet all NIF specifications. Therefore, all the tripler DKDP crystals used in NIF were grown by the traditional method5. Chen et al. successfully used the rapid growth method to grow a cuboid DKDP crystal without a pyramidal sector41. Whether the resulting material grown by this method meets the requirements of the project needs to be further verified.

Crystal characterization

Determination of deuterium content in DKDP crystal

Deuterium content is a very important parameter for DKDP crystal, which is defined as the molar percentage of deuterium in the total number of hydrogen atoms in the crystal lattice. The chemical and physical properties of DKDP crystals are highly sensitive to the deuteration level of DKDP crystals, such as lattice parameters, phase-transition temperature, refractive index, optical properties16,42,43,44. Therefore, an accurate measurement of the degree of deuteration in DKDP crystal is extremely important for its applications in high-power laser systems.

G. M. Loiacono et al. reported the variation in the ferroelectric transition temperature with deuteration in 1974, which was almost dependent linearly on its deuteration level45. Yaksin et al. presented that Raman scattering spectra could be used to measure the deuteration degree of DKDP crystals46. Huser et al. demonstrated that the Raman shift of the main PO4 vibration peak varied linearly with the deuteration level47. Li et al. proposed a new method to measure the deuterium content of DKDP crystals, which mainly used thermo-gravimetric apparatus to weigh the initial DKDP crystal sample and products of thermal decomposition48. Liu et al. found that there was a linear relationship between refractive index and deuteration degree of DKDP crystal, which might become a potential method to determine the deuterium content49. However, all of the above methods measured the variation of the physical and chemical properties of crystals with the deuterium content to determine the deuterium content of DKDP crystals indirectly.

The neutron scattering length of the deuterium atom is larger than that of other atoms in DKDP crystal, so neutron diffraction can be used as an effective technique to directly determine the deuterium content of DKDP crystals50,51. Neutron powder diffraction data were measured by the high-pressure neutron powder diffractometer (Fig. 2). Table 1 showed the deuterium content of DKDP crystals (Dc) grown from different solution deuteration levels (Ds), which could be obtained from the refined neutron diffraction data.

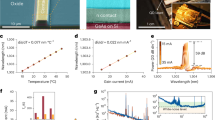

Then the results of neutron diffraction were used to calibrate the relationship between the deuterium content and the variation of PO4 vibration peak in Raman spectra and the absorption bands in IR spectra, respectively. According to the Raman shifts of PO4 vibration peak of KDP and DKDP crystals with different degrees of deuteration (Fig. 3a), the relative Raman shift [Δν1 = ν1(KDP) − ν1(DKDP)] was used to determine the deuterium content of DKDP crystals. There was a linear relationship between the relative Raman shift and Dc (Fig. 3b), as follows:

where ν1(KDP) and ν1(DKDP) were the Raman shifts of the PO4 vibration peak (cm−1) for KDP and DKDP crystals, respectively.

Similarly, the dependence of the variation in β(O-H/D) (it presents stretching vibration of the O-H or O-D bond) and ν1(PO4) of the IR spectra on the deuterium content was showed two different kinds of a linear relationship between them (Fig. 4). When the degree of deuteration was less than 73.8%, the linear relationship was shown as follows:

where β(KDP) and β(DKDP) were the β(O-H/D) absorption bands of KDP and DKDP crystals, respectively. When the degree of deuteration was more than 73.8%, the relationship could become the following Eq.:

Both spectral techniques could be applied to determine the deuterium content of DKDP crystals with solution deuteration level less than 92%, while IR spectroscopy should be more suitable to measure more highly deuterated DKDP crystals.

Homogeneity of deuterium distribution in DKDP crystal

It is well-known that the homogeneity of deuterium distribution in DKDP crystals is very important for optical applications. In the growth process of DKDP crystals, the inhomogeneity of deuterium distribution is closely related to the variation of growth parameters. For a rapidly grown DKDP crystal with the size of 65 mm × 65 mm × 113 mm, the homogeneity of deuterium distribution was measured by the Raman spectra and the results showed the maximum discrepancy of deuterium content was 5.4%36. The effect of supersaturation on deuteration distribution in DKDP crystal was further investigated by Raman and infrared spectroscopy52. The deuterium distributions in DKDP samples with different deuteration levels were obtained (Fig. 5a) and then the homogeneities between pyramidal and prismatic sections were compared (Fig. 5b). The maximum discrepancy of the average deuterium content between the two sections was approximately 2% when the solution deuteration level is 70%, while that of others was less than 1%. The deuteration segregation coefficient of rapid-growth DKDP crystal with high supersaturation was smaller than that of traditional-growth crystal with low supersaturation in solution with the same deuterium content (Fig. 6). For the rapid-growth DKDP crystal grown with different supersaturation, deuterium distributions in crystals were shown in Fig. 7. The results indicated that the deuterium content in the pyramidal section suffered only minimal disruption from variations in supersaturation, while that in the prismatic section presented a large fluctuation (Fig. 7a). The difference in the average deuterium content between the two sections increased with increasing supersaturation, which indicated serious inhomogeneity of deuterium distribution in the whole crystal (Fig. 7b).

a Deuterium distribution in DKDP crystals grown from solutions with different deuterium contents and supersaturation levels ranging from 0.04 to 0.0652 and b difference in the average deuteration levels between the pyramidal and prismatic sections (their size represent the error bars)52. Images reproduced with the following permission: (a)52, (b)52 from Wiley-VCH

a The dependence of average deuterated-level in crystals grown by rapid growth with supersaturation of 0.04 to 0.06 on the deuteration level in solution and empirical formula used to traditional growth crystals52 and b difference in the segregation coefficients of the deuteration level between traditional and rapid growths (average)52. Images reproduced with the following permission: (a)52, (b)52 from Wiley-VCH

The deuterium homogeneities of large-size DKDP crystals grown by traditional growth method and rapid growth method were investigated in situ by Raman spectroscopy, respectively37,53. The results indicated that the inhomogeneity of deuterium content was estimated to be 0.12% for the traditional-growth DKDP crystal, which meant its influence on the third harmonic generation (THG) efficiency could be neglected. However, the deuterium gradient was about 0.2% cm−1 for the rapid-growth DKDP crystal, which will lead to about a 5% reduction of the THG efficiency at 3 GW cm−2 of fundamental radiation37.

Residual strain and stress in single crystal

In the growing and machining process of DKDP crystals, residual stress can be introduced in the crystal by the lattice deformation, which may be caused by some unavoidable changes such as the H/D isotopic exchange, temperature variation, defect generation, introduction of external forces50,54,55,56. The residual stresses not only affect the mechanical properties of the crystal but also affect the other properties. Thus, it is very important to investigate the residual stress in DKDP crystal for its applications in high power laser systems.

The residual stress in a single crystal is characterized mainly by the photoelastic method, X-ray technique, and neutron diffraction technique. Compared with the other two methods, the neutron diffraction technique has obvious advantages for its deep penetrability through most of the materials without damage occurring, which has been maturely applied to the research of stress and strains in polycrystal materials57,58,59.

DKDP crystals with different deuterium contents were grown by rapid growth method and the three-dimensional (3D) residual strains in single crystals were investigated by neutron diffraction technique52,60. The magnitude of residual strains (εij) in crystallographic coordinate was 10−3 to 10−4 and the normal strains along [001] direction were always compressive (Table 2). Then according to the values of macroscopic strains (εij) 60 and elastic stiffness constant (Cij)61, the residual stresses were calculated by Hooke’s law. It was illustrated that the value of shear stress was much smaller than that of normal stress and the magnitude of the macro-strain in DKDP crystals was independent of the deuterium content (Table 3). The average micro-strains of the {323} faces were calculated from the values of full-width at half-maximum for the diffraction peaks (Fig. 8), which indicated that there was a trend of increasing first and then decreasing for the average the micro-strain, with the maximum value occurring at 50% deuterium. In addition, the potential sources of the residual strains and stresses in single crystals were attributed to the defects including dislocations, interstitial defects, and vacancy defects. However, the influence of these defects on the macroscopic stress needs further research.

Nonlinear optical property of DKDP crystal

The absorption of UV light usually increases nonlinearly with the irradiated laser intensity, which has become one of the major problems for the frequency-conversion crystal. A. Melninkaitis et al. found that when the energy density increased from 0.1 J cm−2 to 3 J cm−2, the absorption of KDP crystal with a length of 1 cm at 355 nm increased 1.9%62. The nonlinear absorption (NLA) is usually attributed to multiphoton absorption. For the frequency-conversion crystals, the NLA not only results in the energy loss of the laser beam but also causes potential damage to the crystals63,64. At present, the NLA of KDP crystals at different wavelengths have been investigated, while the research for the NLA of DKDP crystals has been few reported65,66,67,68.

The NLA of DKDP crystals with deuterium content of 70% was measured by the Z-scan method using the nanosecond and picosecond Nd: YAG laser with a wavelength of 355 nm, respectively69,70. Both results showed that the NLA at 355 nm was assigned to two-photon absorption (Fig. 9). The NLA and nonlinear refraction (NLR) of DKDP crystals were obviously influenced by thermal annealing, which decreased with the increasing annealing temperatures (Figs. 10 and 11). In addition, the laser-induced damage of 70% deuterated DKDP crystal was considered to relate to NLA and NLR, which should be further researched.

Improvements on laser-induced damage resistance

The most important property of KDP and DKDP crystal used as nonlinear optics in high power laser systems such as NIF or SG III is the laser-induced damage resistance. The mechanism of laser-induced damage for these materials and how to improve their resistance to laser damage have attracted intensive attention since the construction of the large-aperture laser system for the Inertial Confinement Fusion. From the perspective on the microstructure of crystalline materials, many microscopic-scale defects such as impurities, dislocations, inclusions, growth boundaries, etc. generated during the growth of single crystals and their influences on laser induced damage have been studied71,72,73. Along with the improvement in the material manufacturing process, the above-mentioned defects can be well removed or controlled at a very low level, and studies have shown that the damage phenomenon of crystal optics is not substantially related to those defects. From the reported damage behavior and mechanism of crystal optics irradiated by ultraviolet laser with high fluences, the initial bulk damage of crystal is related to the nano-scale cluster defects inside the material, which become the light absorption center when irradiated by high power laser16,74. The damage characteristics of materials are closely related to the size and density of absorbing defects. The distribution of such absorbent defects is well below the detection limit of common optical techniques, so it is difficult to obtain complete information such as their chemical species, sizes, and distribution characteristics.

At the beginning of research on DKDP crystal growth, the effect of purity of raw materials and variable crystal growth parameters on the laser-induced damage property have been investigated. Although the thermal annealing method which has been confirmed for effectively improving the optical property of KDP crystal is seldom used for DKDP crystal as its lower phase transition temperature. Improved thermal annealing for DKDP crystal will be introduced here, as well as laser conditioning. Moreover, the connection between the growth parameters and the laser induced damage resistance of DKDP crystals could be revealed from the defects generated during the growth process. Some experiments and theoretical studies on the effect of defects on the properties of KDP/DKDP crystals will be present in the third section.

Impurities and growth conditions

Normally, there always exist some impurities in the aqueous solution for DKDP crystal growth. The impurities in the solution may come from starting salts, deuterated water, intention dopants, or dissolved materials of the vessel. Even now the nature origin of bulk damage is unclear, or no impurities or defects that are directly related to the formation of pinpoint damage have been detected. The impurities with ion state in the solution could be absorbed on the growing surface and modify the movement of the growth steps, the growth habit, and the crystallinity of DKDP crystals.

In our previous work, we concentrated on impurities from the starting salt. Sun et al.75 have used the conventional temperature-reduction method to grow KD2PO4 (DKDP) crystals from 85% deuterated solution synthesized by two kinds of KH2PO4 (KDP) starting salts. The crystals which were grown from material containing higher-level metallic impurity (Fe~10 ppm) have more ultraviolet optical absorption than that grown from material with lower-level impurity (Fe~1 ppm). The crystal grown with high purity material has superior laser damage resistance at 1064 nm, but no significant difference (<15%) at 355 nm compared to the crystal grown with lower purity material. Liu et al.76 have used three kinds of KH2PO4 salts (named as A, B, and C; A and B were purer than C, the mass content of main metal ions were below 1 ppm) to grow DKDP crystals by conventional and rapid growth methods, respectively. The 1-on-1 testing damage probabilities curves of these DKDP crystals are shown in Fig. 12. For conventional growth, the difference in material purity does not lead to a visible variation of damage probabilities between the three crystals A1, B1, and C1. Normally, the rapidly grown crystals have poor laser damage resistance compared with the conventionally grown crystals. However, there will be comparable damage resistance to conventionally grown crystals when the crystal is grown at a lower growth rate (e.g., about 3 mm day−1 for crystal C2). With identical other growth parameters, the damage resistance in DKDP is slightly independent of raw material with the mass content of main metallic impurity below 1 ppm.

Burnham et al.72 have reported that laser induced pinpoint bulk damage of DKDP crystals at 351 nm depends on growth conditions such as growth temperature, and continuous filtration. Negres et al.77 have proved that the damage performance of DKDP crystals was dependent on growth temperature and non-correlated with impurity concentration. In addition, the damage resistance in DKDP is independent of the growth rate at constant growth temperature. In our work, continuous filtration is a key procedure during the process of large-aperture DKDP crystal grown in a 1000 L crystallizer. It was found that the samples from different locations within the boule of conventionally grown DKDP crystal with continuous filtration have a slight difference in laser damage resistance at 355 nm (Table 4). Like the previous report, the sample from the last grown pyramidal section (represent material grown at low temperature) has higher laser damage resistance. Moreover, we have grown four DKDP crystals with 60% deuterated level at different temperatures using the point seed technique but without continuous filtration. The aspect ratio of crystal grown at high temperature is higher than that grown at low temperature. The crystalline perfection and the laser induced damage threshold at 1064 nm decrease with the decrease of growth temperature. DeMange et al.78,79 have reported that precursors responsible for damage initiation at 1064 nm are different from those at 355 nm. Thus, there appears a different trend for laser damage resistance at 1064 nm.

Thermal annealing and laser conditioning

In addition to using high-purity raw materials and optimizing growth processes, additives, dopants, and post-treatment can also be used to improve the quality of the KDP and DKDP crystals. The post-treatment including thermal annealing and laser conditioning could be used to increase the activation energy of lattice motion, release excess energy, reduce the internal stress of the crystal, and improve the crystallinity. Then the laser damage resistance and optical homogeneity can be improved.

Early in the 1980s, Swain et al.80,81 have investigated the effect of subthreshold irradiation on the 1064 nm bulk laser damage resistance of KDP crystals. The combination of baking (thermal annealing) and laser irradiation with sub-threshold fluence was more effective in improving the bulk damage threshold for all laser pulse duration from 1 to 20 ns. Fujioka et al.82 also proved that the thermal conditioning was effective for the rapidly grown crystals to improve the damage threshold (1064 nm, 1 ns, 1- on - 1 test), as well as reducing the strain in the crystal. Guillet et al. have reported that thermal annealing could indeed improve laser damage resistance at 3ω for DKDP crystal, the resistance increment depends on the pulse length83. In Fu’s work84, the optical homogeneity of the samples for KDP and DKDP have been improved after thermal conditioning, while the laser damage threshold and light absorption coefficient showed no significant change. Sun et al. also confirmed that thermal conditioning was an effective method to improve the transmittance in ultraviolet wavelength and no improvement on laser damage thresholds for both 1ω and 3ω75. The thermal annealing temperature is usually below 363 K for DKDP crystals, while the annealing temperature of KDP crystals is about 423 K. The relative low annealing temperature leads to no significant improvement of thermal annealing on the laser damage resistance for DKDP crystals. Thus, we investigated in detail the high temperature phase transition of KD2PO4 crystal. And a new annealing method was developed by using silicone oil as a protective ambient environment under higher temperatures, the hydrogen-deuterium exchange can be inhibited under this environment85. After the annealing process (Fig. 13), the crystallinity of the DKDP crystal is improved (Fig. 14). Moreover, the improvement on 3ω laser damage resistance after thermal annealing was confirmed by Cai et al. (Fig. 15)70. This new thermal annealing method has been set as an important procedure in our production of large-aperture DKDP optics.

Since laser conditioning by pre-exposure to subthreshold laser pulse have been proved as an effective method to improve the laser damage resistance for KDP and DKDP crystals. Protocols for laser conditioning on optics used in large-aperture laser systems gain intensive attention from researchers, as well as the characteristics and mechanisms of laser conditioning for KDP/DKDP crystals11,86,87,88,89,90. Zhao and Hu have studied the absorption property and mitigation of scattering defects for DKDP crystals after laser conditioning91,92,93. We have measured the laser induced damage threshold of many DKDP crystals, one typical result is given in Table 5. It can be seen that the LIDT of R-on-1 measurement which has the effect of laser conditioning is obviously higher than that of 1-on-1 measurement. The efficiencies of laser conditioning are dependent on the growth process of DKDP crystals. Liao et al. developed an Absorption Distribution Model (ADM) to map the defect population variability in DKDP crystals90. It’s necessary to use this kind of model to optimize the laser conditioning protocol for crystals with different damage qualities.

Defects for damage initiation in KDP/DKDP crystal

In the past decades, many efforts including experimental measurements or theoretical studies have been devoted to exploring the defects in KDP/DKDP crystals which are thought to be relative to the laser damage initiation94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103. The observed results based on microscopic techniques such as laser scatter diagnostic and fluorescence microscopy has indicated that the scattering defects and fluorescent clusters didn’t strongly correlate to the location of bulk damage sites94,98. The experimental work using optical absorption and electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopies has identified four main intrinsic (atomic) defects in KDP crystals, such as [HPO4]− center, [HPO4]0 center, (H)0 atoms, and [PO3]2− center95,96,97. S. G. Demos et al.16 developed a novel experimental approach to probe the electronic structure of damage precursors. In their experiment, the sample was irradiated to spatially and temporally overlapping 2ω and 3ω pulses at various fluence combinations and the density of pinpoint damage sites as a function of the ratio of the 3ω effective fluence over the corresponding 2ω fluence was estimated. The results could be reproduced by using a multi-level electronic structure model. Based on the experimental observations and the modeling results, they proposed that clusters of holes trapped near oxygen sites are the constituent defects of the damage precursors. However, it remains a challenge to directly detect this kind of defect in experiment.

On the other hand, theoretical studies by density functional theory have been carried out to investigate the electronic structure of point defects in KDP crystal. The modeling results such as band-gap narrowing or a new state in the band-gap can explain the variation of optical absorption property for this material. In our recent works, the first-principle method was applied to investigate the intrinsic, interstitial, and metal ion defects in KDP and ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (ADP) crystals104,105,106,107,108. However, crystal defects often do not exist singly but combine to form clusters. Thus, Sui et al. have investigated the structure, stability, and electronic structures of the oxygen vacancy cluster defect and Fep2− + Vo2+ cluster defect for the KDP crystal. The partial density of states (PDOS) of the oxygen vacancy and cluster defects are shown in Figs. 16 and 17108. The concentration of oxygen vacancy defects has little effect on the electronic structure, only leading to the torsion of the surrounding bonds. The defect state induced by Fep2− defect could introduce three defect states at 0.5, 1.2, and 4.0 eV, respectively. When the Fep2− + Vo2+ cluster defect forms, these defect states shift about 1.0 eV close to conduction band minimum (CBM). This variation would influence the transient optical absorption under irradiation by a high-intensity laser pulse. As the most common defects in KDP/DKDP crystals, we also studied the effect of dislocation by theoretical modeling. The structure, total system energies, electronic structures, and optical absorption of the [010] and [011] screw dislocations in KDP crystals have been investigated using the density functional theory with Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof and Heyd-Suseria-Ernzerhof (HSE06) functionals109,110. The results show that these dislocations would contribute to a large nonlinear absorption, enhance the crystal to absorb more laser energy, and decrease the laser-induced damage threshold of the KDP crystal.

Conclusios and perspectives

Large-aperture high-quality DKDP crystals have been successfully grown by the traditional method, which can fabricate the large single-crystal optics with size exceeding 400 mm. Raman spectroscopy as a non-destructive detection method is applied to determine the deuterium content and its distribution in DKDP crystal, which has been calibrated by neutron diffraction. The three-dimensional residual strains in DKDP crystals with different deuterium contents are investigated by neutron diffraction technique. However, the pathway by which the defects affect the macroscopic stress in the grown crystal needs further research. The nonlinear absorption of 70% deuterated DKDP crystal at 355 nm has been assigned as two-photon absorption with the Z-scan method, which may contribute to the laser-induced damage.

For the preparation of DKDP crystals with excellent laser damage resistance, the purity of raw materials, continuous filtration technology, thermal annealing and laser conditioning are all key factors. Although the laser damage mechanism and laser conditioning mechanism are still not well understood, improvements of these processes enables the grown crystals to meet the specifications of the ICF laser system. Another remaining challenge is the lack of techniques to effectively characterize defects associated with the laser damage initiation. This makes it difficult to implement more efficient process improvements to further enhance the damage resistance of DKDP crystals. The simulation results of theoretical calculations can provide further insights into the experimental observations to a certain extent. Considering the difference brought about by isotopic effect, developing the pseudopotential of deuterium atom can make future theoretical calculations for DKDP crystals more accurate. In addition, as nonlinear optical crystals with outstanding performance, the applications of KDP/DKDP crystals and their analogs in fourth frequency generation, true zero-order waveplate, optical parametric chirped pulse amplification (OPCPA) still require further research.

References

Clery, D. Laser-powered fusion effort nears 'ignition'. Science 373, 841 (2021).

Zaitseva, N. & Carman, L. Rapid growth of KDP-type crystals. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 43, 1–118 (2001).

Hawley-Fedder, R. et al. NIF Pockels cell and frequency conversion crystals. In Proceedings of SPIE 5341, Optical Engineering at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory II: The National Ignition Facility 121–126 (San Jose: SPIE, 2004).

De Yoreo, J. J., Burnham, A. K. & Whitman, P. K. Developing KH2PO4 and KD2PO4 crystals for the world's most power laser. Int. Mater. Rev. 47, 113–152 (2002).

Baisden, P. A. et al. Large optics for the national ignition facility. Fusion Sci. Technol. 69, 295–351 (2016).

Maunier, C. et al. Growth and characterization of large KDP crystals for high power lasers. Optical Mater. 30, 88–90 (2007).

Barker, C. E. et al. Transverse stimulated Raman scattering in KDP. In Proceedings of SPIE 2633, Solid State Lasers for Application to Inertial Confinement Fusion (ICF) 501–505 (Monterey: SPIE, 1995).

Demos, S. G. et al. Measurement of the Raman scattering cross section of the breathing mode in KDP and DKDP crystals. Opt. Express 19, 21050–21059 (2011).

Stuart, B. C. et al. Laser-induced damage in dielectrics with nanosecond to subpicosecond pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2248–2251 (1995).

Natoli, J. Y. et al. Influence of laser beam size and wavelength in the determination of LIDT and associated laser damage precursor densities in KH2PO4. Proceedings of SPIE 6720, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2007. Boulder: SPIE, 2007, 672016

DeMange, P. et al. Multiwavelength investigation of laser-damage performance in potassium dihydrogen phosphate after laser annealing. Opt. Lett. 30, 221–223 (2005).

Carr, C. W., Radousky, H. B. & Demos, S. G. Wavelength dependence of laser-induced damage: determining the damage initiation mechanisms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 127402 (2003).

Manenkov, A. A. & Prokhorov, A. M. Laser-induced damage in solids. Sov. Phys. Uspekhi 29, 104–122 (1986).

Wood, R. M. Laser-induced damage of optical materials. (Bristol: Institute of Physics, 2003).

Koldunov, M. F., Manenkov, A. A. & Pokotilo, I. L. Efficiency of various mechanisms of the laser damage in transparent solids. Quantum Electron. 32, 623–628 (2002).

Demos, S. G. et al. Investigation of the electronic and physical properties of defect structures responsible for laser-induced damage in DKDP crystals. Opt. Express 18, 13788–13804 (2010).

Demos, S. G. et al. Imaging of laser-induced reactions of individual defect nanoclusters. Opt. Lett. 26, 1975–1977 (2001).

Lu, Z. K. et al. Growth of large KDP crystals by solution circulating method. J. Synth. Cryst. 25, 19–22 (1996).

Zaitseva, N. P., Rashkovich, L. N. & Bogatyreva, S. V. Stability of KH2PO4 and K (H, D) 2PO4 solutions at fast crystal growth rates. J. Cryst. Growth 148, 276–282 (1995).

Sun, S. T. et al. Effects of raw material on the growth habit and optical properties of DKDP crystal. J. Synth. Cryst. 38, 539–543 (2009).

Sun, S. T. et al. Effects of growth method on the growth habit and optical property of DKDP crystals. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 37, 1914–1918 (2009).

Sun, S. T. et al. Study on the growth habit and optical property of DKDP crystal grown by different seed. J. Funct. Mater. 40, 1955–1957 (2009).

Xu, M. X. et al. Effect of deuterium content on the optical properties of DKDP crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 53, 1700298 (2018).

Nakatsuka, M. et al. Rapid growth over 50 mm/day of water-soluble KDP crystal. J. Cryst. Growth 171, 531–537 (1997).

Zaitseva, N. P. et al. Rapid growth of large-scale (40-55 cm) KH2PO4 crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 180, 255–262 (1997).

Hawley-Fedder, R. et al. Rapid growth of very large KDP and KD*P crystals in support of the national ignition facility. In Proceedings of SPIE 4102, Inorganic Optical Materials II 152–161 (San Diego: SPIE, 2000).

Zhuang, X. X. et al. The rapid growth of large-scale KDP single crystal in brief procedure. J. Cryst. Growth 318, 700–702 (2011).

Li, G. H. et al. Rapid growth of a large-scale (600 mm aperture) KDP crystal and its optical quality. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 2, e2 (2014).

Zhang, L. Y. et al. Research progress of oversized KDP/DKDP. Cryst. J. Synth. Cryst. 50, 724–731 (2021).

Zaitseva, N. et al. Design and benefits of continuous filtration in rapid growth of large KDP and DKDP crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 197, 911–920 (1999).

Zhang, L. S. et al. Study on rapid growth of 98% deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate (DKDP) crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 401, 190–194 (2014).

Zhang, L. S. et al. Rapid growth of a large size, highly deuterated DKDP crystal and its efficient noncritical phase matching fourth-harmonic-generation of a Nd: YAG laser. RSC Adv. 5, 74858–74863 (2015).

Cai, X. M. et al. Rapid growth and properties of large-aperture 98%-deuterated DKDP crystals. High. Power Laser Sci. Eng. 7, e46 (2019).

Chen, D. Y. et al. Investigation of the pyramid-prism boundary of a rapidly grown KDP crystal. CrystEngComm 21, 1482–1487 (2019).

Xu, L. Y. et al. A study on nonlinear absorption uniformity in a KDP crystal at 532 nm. CrystEngComm 22, 5338–5344 (2020).

Ji, S. H. et al. Homogeneity of rapid grown DKDP crystal. Opt. Mater. Exp. 4, 997–1002 (2014).

Chai, X. X. et al. Deuterium homogeneity investigation of large-size DKDP crystal. Opt. Mater. Exp. 8, 1193–1201 (2018).

Chai, X. X. et al. Research on the growth interfaces of pyramidal and prismatic sectors in rapid grown KDP and DKDP crystals. Opt. Mater. Exp. 9, 4605–4613 (2019).

Zaitseva, N., Carman, L. & Smolsky, I. Habit control during rapid growth of KDP and DKDP crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 241, 363–373 (2002).

Liu, F. F. et al. Effect of supersaturation on hillock of directional Growth of KDP crystals. Sci. Rep. 4, 6886 (2014).

Chen, D. Y. et al. Rapid growth of a cuboid DKDP (KDxH2–x PO4) crystal. Cryst. Growth Des. 19, 2746–2750 (2019).

Fu, D. W., Zhang, W. & Xiong, R. G. Isotope effect on SHG response and ferroelectric properties of a homochiral zinc coordination compound containing tetrazole Ligand. Cryst. Growth Des. 8, 3461–3464 (2008).

Tachikawa, M. et al. First-principle calculation on isotope effect in KH2PO4 and KD2PO4 of hydrogen-bonded dielectric materials. approach with dynamic extended molecular orbital method. Ferroelectrics 268, 3–9 (2002).

Xu, M. X. et al. Study on the properties of the DKDP crystal with different deuterium content. Proceedings of SPIE 8206, Pacific Rim Laser Damage 2011: Optical Materials for High Power Lasers. Shanghai: SPIE, 2012, 82062B.

Loiacono, G. M., Balascio, J. F. & Osborne, W. Effect of deuteration on the ferroelectric transition temperature and the distribution coefficient of deuterium in K(H1−xDx)2PO4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 24, 455–456 (1974).

Yakshin, M. A. et al. Determination of the deuteration degree of DKDP crystals by Raman spectroscopy technique. Laser Phys. 7, 941–945 (1997).

Huser, T. et al. Characterization of proton exchange layer profiles in KD2PO4 crystals by micro-Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Spectrosc. 58, 349–351 (2004).

Li, G. H. et al. A new method to determine the deuterium content of DKDP crystal with thermo-gravimetric apparatus. Optical Mater. 29, 220–223 (2006).

Liu, W. J. et al. Dependence of refractive indices on deuterium content in K(H1−xDx)2PO4 crystals. Opt. Laser Technol. 44, 1769–1772 (2012).

Tun, Z. et al. A high-resolution neutron-diffraction study of the effects of deuteration on the crystal structure of KH2PO4. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 21, 245–258 (1988).

Liu, F. F. et al. Determination of deuteration level of K (H1−xDx)2PO4 crystal. Opt. Mater. Exp. 6, 2221–2228 (2016).

Liu, F. F. et al. Effect of supersaturation on deuteration distribution in K(H1−xDx)2PO4 crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 51, 681–687 (2016).

Chai, X. X. et al. Noncritical phase-matched fourth harmonic generation properties of traditional grown large-size DKDP crystal. Opt. Commun. 392, 162–166 (2017).

Belouet, C., Monnier, M. & Verplanke, J. C. Autoradiography as a tool for studying iron segregation and related defects in KH2PO4 single crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 29, 109–120 (1975).

Zaccaro, J. et al. Origin of crazing in deuterated KDP crystals. Cryst. Growth Des. 14, 6581–6588 (2014).

Dam, B. et al. On the formation of etch grooves around stress fields due to inhomogeneous impurity distribution in KH2PO4 single crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 51, 607–623 (1981).

Fitzpatrick, M. E. & Lodini, A. Analysis of residual stress by diffraction using neutron and synchrotron radiation. (Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2003).

Jiang, W. C. et al. Neutron diffraction measurement and numerical simulation to study the effect of repair depth on residual stress in 316L stainless steel repair weld. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 137, 041406 (2015).

Chen, X. Z. et al. Residual stresses determination in an 8 mm Incoloy 800H weld via neutron diffraction. Mater. Des. 76, 26–31 (2015).

Liu, F. F. et al. 3D residual strain in DKDP crystals by neutron diffraction. Cryst. Res. Technol. 54, 1900022 (2019).

Straube, U. & Beige, H. Third order elastic coefficients of KDP at room temperature. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 3, S459-–S4460 (1998).

Melninkaitis, A. et al. Characterization of the KDP crystals used in large-aperture doublers and triplers. In Proceedings of SPIE 5647, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2004 298–305 (Boulder: SPIE, 2004).

Veitas, G. et al. Efficient femtosecond pulse generation at 264 nm. Opt. Commun. 138, 333–336 (1997).

Begishev, I. A. et al. Generation of the fifth harmonic of a neodymium laser and two-photon absorption in KDP and ADP crystals. Sov. J. Quantum Electron. 18, 224–228 (1988).

Chai, X. X. et al. Nonlinear absorption properties of DKDP crystal at 263 nm and 351 nm. Optical Mater. 64, 262–267 (2017).

Wang, D. L. et al. Effect of Fe3+ on third-order optical nonlinearity of KDP single crystals. CrystEngComm 18, 9292–9298 (2016).

Liu, P. et al. Absolute two-photon absorption coefficients at 355 and 266 nm. Phys. Rev. B 17, 4620–4632 (1978).

Divall, M. et al. Two-photon-absorption of frequency converter crystals at 248 nm. Appl. Phys. B 81, 1123–1126 (2005).

Cai, D. T. et al. Third-harmonic-generation nonlinear absorption coefficient of 70% deuterated DKDP crystal. Optical Mater. Express 7, 4386–4394 (2017).

Cai, D. T. et al. Effect of annealing on nonlinear optical properties of 70% deuterated DKDP crystals at 355 nm. CrystEngComm 20, 7357–7363 (2018).

Woods, B. W. et al. Investigations of laser damage in KDP using light-scattering techniques. In Proceedings of SPIE 2966, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 1996 20–31 (Boulder: SPIE, 1997).

Burnham, A. K. et al. Laser-induced damage in deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate. Appl. Opt. 42, 5483–5495 (2003).

Pommiès, M. et al. Detection and characterization of absorption heterogeneities in KH2PO4 crystals. Opt. Commun. 267, 154–161 (2006).

Feit, M. D. & Rubenchik, A. M. Implications of nanoabsorber initiators for damage probability curves, pulselength scaling, and laser conditioning. In Proceedings of SPIE 5273, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2003 74–82 (Boulder: SPIE, 2004).

Sun, S. T. et al. The effect of material, thermal and laser conditioning on the damage threshold of type II tripler-cut DKDP crystals. Cryst. Res. Technol. 43, 773–777 (2008).

Liu, B. A. et al. Effect of raw material and growth method on optical properties of DKDP crystal. Chin. Opt. Lett. 12, 101604 (2014).

Negres, R. A. et al. Expedited laser damage profiling of KDxH2−xPO4 with respect to crystal growth parameters. Opt. Lett. 31, 3110–3112 (2006).

DeMange, P. et al. Differentiation of defect populations responsible for bulk laser-induced damage in potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals. Opt. Eng. 45, 104205 (2006).

DeMange, P. et al. Laser-induced defect reactions governing damage initiation in DKDP crystals. Opt. Exp. 14, 5313–5328 (2006).

Swain, J. et al. Improving the bulk laser damage resistance of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals by pulsed laser irradiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 40, 350–352 (1982).

Swain, J. E. et al. The effect of baking and pulsed laser irradiation on the bulk laser damage threshold of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 41, 12–14 (1982).

Fujioka, K. et al. Optical properties of rapidly grown KDP crystal improved by thermal conditioning. J. Cryst. Growth 181, 265–271 (1997).

Guillet, F. et al. Effects of thermal annealing on KDP and DKDP on laser damage resistance at 3ω. In Proceedings of SPIE 7842, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2010 78421T (Boulder: SPIE, 2010).

Fu, Y. J. et al. Study on K(DxH1−x)2PO4 crystals: growth habit, optical properties and their improvement by thermal-conditioning. Cryst. Res. Technol. 35, 177–184 (2000).

Zhang, L. S. et al. New annealing method to improve KD2PO4 crystal quality: learning from high temperature phase transition. CrystEngComm 17, 4705–4711 (2015).

Negres, R. A., DeMange, P. & Demos, S. G. Investigation of laser annealing parameters for optimal laser-damage performance in deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate. Opt. Lett. 30, 2766–2768 (2005).

Adams, J. J. et al. Pulse length dependence of laser conditioning and bulk damage in KD2PO4. In Proceedings of SPIE 5647, Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 2004 265–278 (Boulder: SPIE, 2005).

DeMange, P. et al. Laser annealing characteristics of multiple bulk defect populations within DKDP crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 103103 (2008).

Duchateau, G. Simple models for laser-induced damage and conditioning of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals by nanosecond pulses. Opt. Express 17, 10434–10456 (2009).

Liao, Z. M. et al. Predicting laser-induced bulk damage and conditioning for deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals using an absorption distribution model. Opt. Lett. 35, 2538–2540 (2010).

Hu, G. H. et al. One-on-One and R-on-One Tests on KDP and DKDP crystals with different orientations. Chin. Phys. Lett. 26, 087801 (2009).

Hu, G. H. et al. Transmittance increase after laser conditioning reveals absorption properties variation in DKDP crystals. Opt. Express 20, 25169–25180 (2012).

Wang, Y. L. et al. Mitigation of scattering defect and absorption of DKDP crystals by laser conditioning. Opt. Express 23, 16273–16280 (2015).

Runkel, M. J. et al. Analysis of high-resolution scatter images from laser damage experiments performed on KDP. In Proceedings of SPIE 2714, 27th Annual Boulder Damage Symposium: Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials: 1995 185–195 (Boulder: SPIE, 1996).

Setzler, S. et al. Hydrogen atoms in KH2PO4 crystals. Phys. Rev. B 57, 2643–2646 (1998).

Stevens, K. T. et al. Identification of the intrinsic self-trapped hole center in KD2PO4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 75, 1503–1505 (1999).

Chirila, M. M. et al. Production and thermal decay of radiation-induced point defects in KD2PO4 crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 94, 6456–6462 (2003).

Demos, S. G., Staggs, M. & Radousky, H. B. Bulk defect formations in KH2PO4 crystals investigated using fluorescence microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 67, 224102 (2003).

Liu, C. S. et al. electron-or hole-assisted reactions of h defects in hydrogen-bonded kdp. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 015505 (2003).

Liu, C. S. et al. Electronic structure calculations of intrinsic and extrinsic hydrogen point defects in KH2PO4. Phys. Rev. B 68, 224107 (2003).

Liu, C. S. et al. Electronic structure calculations of an oxygen vacancy in KH2PO4. Phys. Rev. B 72, 134110 (2005).

Wang, K. P. et al. First-principles study of interstitial oxygen in potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystals. Phys. Rev. B 72, 184105 (2005).

Li, L. et al. Sulfate may play an important role in the wavelength dependence of laser induced damage. Opt. Express 14, 12196–12198 (2006).

Sui, T. T. et al. Stability and electronic structure of hydrogen vacancies in ADP: hybrid DFT with vdW correction. RSC Adv. 8, 6931–6939 (2018).

Sui, T. T. et al. Comparison of hydrogen vacancies in KDP and ADP crystals: a combination of density functional theory calculations and experiment. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 6186–6197 (2019).

Sui, T. T. et al. Comparison of oxygen vacancy and interstitial oxygen in KDP and ADP crystals from density functional theory calculations. Comput. Mater. Sci. 182, 109783 (2020).

Sui, T. T. et al. Structural stress and extra optical absorption induced by the intrinsic cation defects in KDP and ADP crystals: a theoretical study. CrystEngComm 22, 1962–1969 (2020).

Sui, T. T. et al. Hybrid density functional theory for the stability and electronic properties of Fe-doped cluster defects in KDP crystal. CrystEngComm 23, 7839–7845 (2021).

Jiang, X. Y. et al. First-principles studies on optical absorption of [010] screw dislocation in KDP crystals. CrystEngComm 23, 7412–7417 (2021).

Jiang, X. Y. et al. Theoretical analysis of electronic structure and optical properties of potassium dihydrogen phosphate crystal affected by [011] screw dislocation. Cryst. Growth Des. 22, 1764–1769 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported part by the Young Scholars Program of Shandong University (Grant No. 2018WLJH65) and the Fundamental Research Funds of the Central Universities. The authors also thank the support of neutron diffraction technique from Institute of Nuclear Physics and Chemistry, China Academy of Engineering Physics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, M., Liu, B., Zhang, L. et al. Progress on deuterated potassium dihydrogen phosphate (DKDP) crystals for high power laser system application. Light Sci Appl 11, 241 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00929-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-022-00929-y

This article is cited by

-

400nm ultra-broadband gratings for near-single-cycle 100 Petawatt lasers

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Special Issue on the 120th Anniversary of Shandong University

Light: Science & Applications (2023)