Abstract

Background

A growing number of athletes return to elite sport following childbirth. Yet, they face significant barriers to do so safely and successfully. The experiences of elite athletes returning to sport following delivery are necessary to support evidence-informed policy.

Objective

The purpose of this qualitative description was to describe the experiences of elite athletes as they returned to sport following childbirth, and to identify actionable steps for research, policy and culture-change to support elite athlete mothers.

Methods

Eighteen elite athletes, primarily from North America, who had returned to sport following childbirth in the last 5 years were interviewed. Data were generated via one-on-one semi-structured interviews that were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed through a process of content analysis.

Results

The findings of this study are represented by one overarching theme: Need for More Time, and five main themes: (a) Training “New Bodies” Postpartum, (b) Injuries and Safe Return to Sport, (c) Breastfeeding While Training, (d) Critical Supports for Return to Sport, (e) Navigating Motherhood and Sport. The athletes identified the urgent need to develop best-practice policies and funding to support return to sport, as well as develop evidence-based return-to-sport protocols to support a safe and injury-free return.

Conclusion

Athletes shared detailed stories highlighting the challenges, barriers and successes elite athletes experience returning to elite-level sport following childbirth. Participants provided clear recommendations for policy and research to better support the next generation of elite athlete mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

There are limited supports for female elite athletes to return to sport following pregnancy. |

Interviews with female elite athletes identified a wide range of barriers that limit return to high-level sport following childbirth. This study outlines key actionable steps, including policy recommendations that can be implemented by sporting organizations to support postpartum athletes. |

Research supporting the development and implementation of evidence-based best practice return to sport protocols following childbirth will optimize a safe and injury-free return to sport. |

1 Introduction

Mothers have been competing (and succeeding) at elite sport for over a century. Mary Abbott was the first Olympic mother, coming in seventh place at the 1900 Paris Olympics. Although dozens of Olympians have competed while pregnant or postpartum in the subsequent years, motherhood is generally viewed by the public as incompatible with elite sport. We previously reported on the challenges facing elite athletes who trained and competed during pregnancy [1]. Yet, the postpartum period, from immediately after delivery until the infant is 12 months of age, [2] is a critical window of time; women face unique physiological, mental and emotional challenges include a lack of sleep, increased stress and fatigue, and new or persistent medical issues. As well, they have the added challenge of care and concern for their infant [2, 3].

The 2020 Tokyo Olympics publicized the inequities experienced by high-profile athletes who are navigating motherhood alongside sport. Boxer Mandy Bujold, marathoner Aliphine Tuliamuk and basketball player Kim Gaucher all faced major barriers to participating in the Olympics as a direct result of motherhood. Elite athletes are redefining societal norms by making rapid comebacks to elite sport, even breaking personal bests, while balancing their new identity as a mother. However, these athletes have navigated this transition mostly alone, as supports for elite athletes during this period are severely lacking [4].

In 2016, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) convened a meeting of experts in pre- and post-natal exercise to provide evidence-based guidance for elite athletes, and produced five documents reviewing available literature regarding elite pregnant and postpartum athletes [5,6,7,8,9]. These statements strongly demonstrate of the paucity of data supporting safe return to sport. More recently, we conducted an updated systematic review of the literature that demonstrated elite athletes were more likely than sub-elite and recreational athletes to return to training in the first 6× weeks after delivery [10]. Participants also experienced increased rates of injury, likely exacerbated by a rapid return to sport, further illustrating the urgent need to have strong supports and return to training plans for elite athletes. With the growing visibility of mothers engaging in elite sport, there have been increasing calls to action to develop high-quality research, and subsequent evidence-based policies, in this area [9].

It is essential the voices and experiences of elite athlete mothers become foundational in the development of evidence-based policies to support equitable sport environments. While their experiences have generally been under-represented in the vast sport literature, there is an emerging body of research that has focused on the experiences of athlete mothers. For instance, qualitative research with competitive recreational athlete mothers described the various cultural (e.g., the cultural norm that a “good” mother prioritizes her child over herself), personal (e.g., attempting to balance motherhood, work and sport with a limited amount of time), and social (e.g., childcare, emotional support to engage in sport) barriers that impact sport participation [11]. Similar findings have been noted in research that has documented the in-depth experiences of elite athletes who returned to elite-level sport following childbirth [1, 3, 12,13,14,15,16]. In their research with elite distance runners, Appleby and Fisher [14] described how athletes who returned to competition after pregnancy experienced a transformative process in which they negotiated social stereotypes related to motherhood alongside their athletic identities [14]. Darroch and Hillsburg also engaged in interviews to explore how elite-level runners negotiate the competing identities of athlete and motherhood, and found these dual identities can be complementary rather than conflicting [17].

Drawing upon the experiences of two elite athletes, including a para-athlete, Massey and Whitehead [3] shared longitudinal insights into the manner in which such athletes must negotiate athlete, personal and mother identities. They explained how the most challenging identity negotiations occur in the first month postpartum, as this time period involves changes of priorities, feelings of uncertainty, and the navigation of funding and sponsorship changes. Research that has focused on the experiences of athlete mothers has highlighted critical insights into athletes’ complex experiences of trying to navigate social expectations and stereotypes, while at the same time trying to negotiate their new identity as a mother and athlete. Such research also highlights the need for more studies that focus on the voices and experiences of elite athlete mothers to support the development of evidence-informed policies and practices that support complex and unique experiences during pregnancy and postpartum.

There is a critical need for sport organizations and corporate sponsors to improve policies that create more equitable sporting environments for pregnant or postpartum elite athletes [4]. Such policies must be informed by research evidence that is grounded in the experiences of elite athlete mothers. Findings from Darroch, Giles, and McGettigan-Dumas’ work with elite distance runners emphasized the need for “formal sources” that athletes could use for “trustworthy advice” about how to have a safe pregnancy while training at a high intensity [4]. While their research highlights necessary considerations for athletes during pregnancy, it is equally important for athletes to have formal sources that they can draw upon for trustworthy advice about how to train when returning to elite sport after pregnancy.

Various organizations including the Professional Triathlon Organization, Ladies Professional Golf Association and UK Sport have begun to develop policies to address pregnancy discrimination and to ensure the mental and physiological well-being of their athletes. However, the vast majority of sporting bodies lack evidence-based, athlete-centered policies supporting athlete mothers. Furthermore, drawing upon their work with professional footballers in England, Culvin and Bowes argued that when policies do exist, there is a need to “remove the negative stigma attached to using policy” [16]. Culvin and Bowes’ research highlights the current “omissions and inadequacies” of maternity and family policies in the contracts of professional sportswomen. As such, the purpose of this qualitative study was to describe the experiences of elite athletes as they navigate return to sport following childbirth, and to identify actionable steps for research, policy and culture-change to support elite athlete mothers. Specifically, the present study sought to address the following research questions: (1) how do elite athletes describe their experiences of returning to sport following childbirth? and (2) what changes to policy, practice and research are necessary to support elite athlete mothers?

2 Methods

This study was approved by the University of Alberta Institutional Research Ethics Board (PRO00104326). We utilized qualitative description as the study design as it is often used when there is a dearth of knowledge within a subject area, and when a detailed description is sought [18]. Being less interpretive than other qualitative study designs, qualitative description supports researchers in staying “data-near” [19]. This process of staying near to the data facilitates simple or straightforward answers to questions that are relevant to practitioners and policy makers [18], such as how elite female athletes navigate return to sport following pregnancy. Qualitative description has been successfully applied in various other sport and physical activity-related studies, including some of our own research [20, 21]. This research is part of a larger project that is broadly focused on exploring and describing the experiences of athletes as they navigate pregnancy and their return to sport postpartum. We have previously reported on athletes’ experiences of elite sport during pregnancy [1]. Themes, and the supporting data, that represent participants’ experiences as they navigated return-to-sport following pregnancy are reported in the current study.

2.1 Participants

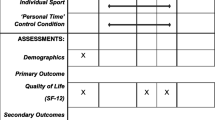

Eighteen athletes from nine Olympic sports (team and individual, winter and summer games) participated in this research. Between January and June 2021, we recruited postpartum elite athletes through social media (i.e., Twitter, Facebook, Instagram) and word of mouth via a purposeful and snowball sampling approach [10]. To be eligible, athletes could reside anywhere in the world, had to be ≥ 18 years old, and must have trained and/or competed at the highest level of their sport immediately prior to, and during, pregnancy, and returned to sport following childbirth within the last 5 years (2016–2021). Twenty-four athletes responded to our request for participants. Two declined to participate, two did not meet our inclusion criteria, and two were currently pregnant with no experience returning to sport postpartum. The athletes were 35 ± 5 years of age, primarily from North America, and most were currently training or competing at the elite level (n = 14; see Table 1). To ensure anonymity of the participants, a complete list of the athletes’ sports is not provided, and pseudonyms have been used in the reporting of the results. However, sporting types included (but were not limited to) weight-bearing and non-weight-bearing sprint and endurance sports, technical sports, ball-game sports and power sports. Athletes would be classified as World Class (n = 8) or Elite/International Level according to the Participant Classification Framework developed [22].

2.2 Data Generation

Prior to participation, individuals provided written, informed consent, and completed a brief questionnaire about their sporting background, demographics, and an overview of their postpartum return-to-sport experiences. Specifically, the questionnaire included items such as the highest level of competition achieved, the duration/type of training during pregnancy, and specifics of delivery (e.g., birth weight). The participant questionnaire (Online Resource 1) is available in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

Qualitative description offers researchers the flexibility to use various forms of data generation and analysis; however, in-depth interviews are often used to explore the nature and shape of participants’ personal experiences [18]. As such, once eligibility was confirmed, participants engaged in a one-on-one semi-structured interview; the interview guide was informed by sport and pregnancy-related literature and a Research Advisory Board (RAB). The all-female RAB included researchers with expertise in qualitative and quantitative research; the researchers also identified as mothers, clinicians and former elite level athletes. The researcher and researcher assistants’ perspectives align with constructionist perspectives. Researchers, such as our team, who are guided by a constructionist epistemological position acknowledge that there is a dialectic relationship between the participants and the researchers, whereby knowledge is co-constructed [23]. As researchers guided by a constructionist perspective we acknowledge that the insights that are co-constructed on a particular topic are grounded in “historically specific and culturally relevant knowledge” [23]. Such knowledge is critical for seeking to describe the experiences of elite athlete mothers.

The interview guide (Online Resource 2, ESM) consisted of 12 major questions relating to athletes' experience (e.g., “Tell me about your experience with return to sport at the elite level following delivery?”). Given the semi-structured nature of this interview guide, the interviewers (i.e., co-authors and RAB members AN and LR) had the flexibility to probe participants to elaborate on specifics provided in their responses. More specifically, having the room to ask probe and follow-up questions beyond the specific questions outlined on the semi-structured interview guide supported the researchers in further exploring each participant’s unique personal and sport histories and cultures, which shaped their experiences of returning to sport after childbirth. Both interviewers have expertise in qualitative processes of data generation, and research interests in psychosocial aspects of sport participation.

Interviews lasted an average of 60 min (range 45–70 min) and took place between January 2021 and June 2021. Interviews took place during the COVID-19 pandemic; thus, all interviews were conducted via video-conferencing that were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by Otter.ai transcription software, and then checked for accuracy. This complied with the University's REB COVID-19 protocols and facilitated the team’s success in recruiting participants who were geographically dispersed across Canada and beyond. As well, immediately following each interview, a narrative summary of each interview was created by the interviewer and shared with members of the RAB.

2.3 Data Analysis

Researchers who employ a qualitative description study design prioritize staying close to the data and presenting a comprehensive summary of the findings. Therefore, content analysis is an ideal approach for analyzing the data generated from the interviews [18]. Elo and Kyngas' three-phase approach (i.e., preparation, organization and reporting) [24] to content analysis was utilized in analyzing the findings of this research project. This three-phase process of content analysis was informed by our team’s constructionist perspective. Specifically, and as noted below, the knowledge generated from this research and represented as findings were co-constructed by the interviewers (AN, LR), members of the RAB, and the participants. In the preparation phase, the verbatim transcripts were checked for accuracy and the unit of analysis was selected (i.e., the words of participants) [24]. To familiarize themselves with the data, the RAB read and re-read the transcripts and narrative summaries. The organization phase involved a process of open-coding. AN and LR led the initial process of “open coding”, whereby they recorded notes in the margins of all transcripts. Other members of the RAB also engaged in a process of open coding to ensure their familiarity with the data as well. The RAB met weekly via Zoom to discuss the project. During such meetings, the team discussed similarities and differences between the codes they had identified. The data were classified, and re-classified, into comprehensive higher order themes until consensus was achieved among the RAB. Results were then shared with all participants, who were asked to provide any feedback or comments to be integrated into the reporting of findings. In terms of the reporting phase of analysis, direct quotes from participants were used to describe and support each theme.

A relativist approach for judging the quality of work varies depending on the purpose of the research. Therefore, we encourage readers to consider the quality of this study based on the worthiness of the topic, coherence and utility [25]. As argued in the Introduction of this article, this topic is worthy of study, as the experiences of elite athletes returning to sport following delivery are limited in the research literature, but necessary to support evidence-informed policy. The coherence of this research is demonstrated by aligning our guiding philosophical approach, with the qualitative descriptive design, participant sampling, data generation, and data analysis. Smith and McGannon described how utility refers to the effectiveness of the design and methods in achieving the study objectives [25]. In terms of this study, we recruited participants who were experts in their own experiences as athletes who had returned to sport following pregnancy. The sharing of these experiences via semi-structured interviews and the analysis of verbatim transcripts via content analysis supported us in achieving the study objectives.

3 Results

Findings are represented by an overarching theme: Need for More Time, and five main themes: (a) Training “New Bodies” Postpartum, (b) Injuries and Safe Return to Sport, (c) Breastfeeding while Training, (d) Critical Supports for Return to Sport, and (e) Navigating Motherhood and Sport. Themes are described and supported by direct quotes from participants. While the themes are presented separately, it is important to note that the themes are not exclusive and there is overlap among the themes.

3.1 Need for More Time

This overarching theme speaks to a common feature among all of the five main themes. That is, participants repeatedly expressed how many of the challenges they experienced when they return to sport could have been alleviated if they were afforded more time prior to returning to sport. They described how there are pressures and expectations for returning to sport after having a baby that are simply not realistic and many of the athletes explained how they wished they would have just given it a little bit more time. As stated by “Jana” (32 years): In the working world, a woman will get one year from her delivery date, usually plus or minus weeks, right? So why are athletes who use their body for work, and their body to carry and make and deliver a baby, expected to be back within six months? We're not superhumans. We are humans.

Similarly, “Leslie” (41 years) explained: It’s really hard to be expected to go back right away. The very same year as you having your baby, you’d be competing with the best in the world to earn your spot back.

Participants outlined various reasons they felt pressure to return to their sport. “Amy” (36 years) said: When you leave the game… a year later, the players are that much faster and that much better. So, you need to not only come back as good as you were, you need to very quickly get better.

“Jana” also explained how a quick return to sport is expected by sponsors and, therefore, there are financial pressures to return: I think there's still a long way to go. Like, some of them [sponsors] only support you up until 6 months after delivery, and then they expect you to be back… And that's, that's not possible. It's not realistic.

“Cassidy” (30 years) shared similar sentiments regarding funding pressures. She said: Well definitely I should have had a little bit more time off or eased back in a little bit slower. But for the funding sake l rushed it a little bit.

In an effort to avoid repetition and to emphasize the range of experiences shared by participants, the “need for more time” is not explicitly described in each of the following five main themes. However, the specific quotes that were intentionally chosen to represent each of the five main themes are meant to highlight, more subtly, the various ways in which “more time” could likely enhance participants experiences of returning to sport following childbirth.

3.2 Training “New” Bodies

Changes to the body, both physical and mental, were identified as key challenges of returning to sport postpartum. Most participants described their experience of some form of frustration, fatigue, and uncertainty with their postpartum bodies. As “Jana” shared: My body wasn't the same. My pelvis didn't sit in the same area. “Tamara” (31 years) also explained how she remembers feeling burnt out after 3 months of her return to sport postpartum. She said: I remember really feeling shitty [doing sport], like really heavy… It really was not enjoyable. It felt physically horrible. And so I did back off quite a bit and take a hiatus from [sport] for a period of time.

In addition to “Tamara”, several athletes described the negative and persisting impact the physical changes had on their performance. As “Nicola” (33 years) shared: I just remember I went to do a [warm up activity], I just fell over, like my spatial awareness. I'm sure my boobs were huge compared to a normal athlete. I was a mess. I felt terrible. It was gross.

Given the various physical changes to their bodies postpartum, some participants, such as “Heidi” (41 years), explained how they were nervous or scared about returning to their sport too early.

Despite the various concerns shared by athletes, infrequently participants highlighted the positive impacts of returning to sport postpartum. “Amy” explained: I felt strong as heck. The hormones after having a baby, I think you can really benefit physically from that. I gained a lot of strength…I think I'm the strongest I've ever been…I definitely took advantage of the hormones, the blood volume. I could feel it more so aerobically. And then as well, in my recovery, like, I would recover so fast. It was crazy. I just felt like I had more energy.

Other participants explained how it took time before they felt like they knew their body after giving birth. Many of the participants explained how they found the return to sport in this new postpartum body difficult. As “Jill” (33 years) stated: I hate that ‘listen to your body again’, because I don't know what that means in this body now, because it's new to me.

In addition to the various physical changes the athletes experienced postpartum, mental and emotional challenges were also described by the participants. “Tanis” (29 years) shared: I definitely experienced a degree of postpartum depression and I never got help or support for that…. figuring out, you know, my role as a mom and athlete, and all of those things…it just it's a lot of that kind of mental stuff to deal with.

“Nicola” shared similar insights: I could have benefited from a sports psych to mentally overcome some of those struggles that I was like internally dealing with.

3.3 Injuries and Safe Return to Sport

Experiences of injury were prominent among many of the athletes’ return to sport postpartum. Participants described how they experienced pelvic organ prolapse, stress fractures, problems with their (sacroiliac) joint and strained abs when they returned to sport. The athletes provided in-depth insights as to the various reasons why they believe that such injuries occur, in addition to the huge trauma of labour and delivery. “Robyn” explained how there are many additional changes to the body that likely increase injury. She said: Elite athletes tend to get injured within a year of pregnancy if they try to come back. And it's just the bone density and breastfeeding, it puts you at risk for bone injuries. And then the lack of sleep and all the changes to your body and everything like that. So it's pretty common to get injured in that first year, enough so that you wouldn't be able to compete at the same level.

The athletes described how they may have been able to avoid injury if they were afforded more time to recover after delivery. Participants also described how there is a need for resources and a support system that will facilitate the safe transition of athletes back into sport after pregnancy. As stated by “Pamela” (35 years): I want to return to sport safely. And I've read enough studies and sort of anecdotal information about, you know, women coming back and getting stress fractures… so just sort of having someone who is comfortable helping me to navigate that, I think, would be really helpful.

“Darcy” shared similar sentiments about the need for a return-to-sport plan that is co-developed by the athlete, coach, and healthcare provider. “Darcy” (31 years) further stated that: Athletes are not going to listen to conservative strategies most of the time, and their bodies are probably more resilient than most.

Participants also acknowledged that there are a lot of pressures from various sources to return to sport quickly. “Mallory” (32 years) shared how some of her younger teammates do not understand the time needed to recover from having a baby. She said: They're very naive about the whole process. And they're like, ‘Well, why aren't you back yet?’ And I'm like, ‘because I had a baby 6 weeks ago, like I can't just come back’.

3.4 Breastfeeding While Training

Participants discussed various considerations regarding breastfeeding while training as an elite athlete. For example, even though it was often difficult to coordinate breastfeeding with training, “Joelle” (30 years) stated: I would have taken [my child] on the road with me anyways, up until he was probably a year old because I'm still nursing. And I enjoy that. And I think it's very important, not pushing it on anybody. And I want to nurse [my child] as long as I can, I guess, within reason.

The athletes discussed the effort that went into coordinating their babies’ feeding schedule around their training. As “Heidi” described: Because you're breastfeeding, your breasts are really full and heavy. Except for when you pump and then they're kind of like, deflated. But they start to fill up right away. So it's kind of like a ticking clock. Some of the athletes explained how they found it best to train immediately following a feeding.

Despite the various considerations given to breastfeeding and training schedules, athletes described the difficulties they still encountered with respect to breastfeeding. As “Jana” shared: I'd want to go [train]. So I'd have to nurse, double up on my sports bra, and call a friend over to come and watch her while she slept. So I can get out for 30 min. And then I come back and have to nurse again. Sometimes just depending on the feed that we had, and I’d be sweaty and she wouldn’t want to eat of course, why would you want to eat off sweaty breasts, that would be awful.

Some participants also explained how they had challenges with milk supply when they returned to training. “Mallory” explained: I think one thing I believe contributed to the drop in my milk supply was [training]. Whether that's true or not, I don't know. But like, I noticed that once the intensity ramped up, once I started going back to [training], once I wasn't sleeping as well, my cortisol levels increased, right? Because I was stressed.

3.5 Critical Supports for Return to Sport

Athletes discussed the importance of having various supports in place to ensure their successful return to sport postpartum. As “Norah” (26 years) shared: If I could see anything changed, honestly, I think giving parents support to pay for childcare…, we have a National Training Centre. So here’s the daycare for the kids while these athletes go and train. As well, funding and organizational support were highlighted as essential components to athletes’ successful return to sport.

Participants described the various challenges, successes and considerations that were given to childcare when they returned to sport. “Cassidy” shared: I didn't really have any support that way, in terms of easy access to childcare, we always had to go find it and pay for it. Other athletes, such as “Stella”, explained how their partner took a paternity leave, which in turn supported their return to sport. As well, some of the athletes also explained how their teams were supportive of athletes bringing their baby to training. “Charlotte” (35 years) shared: Everybody's happy for [baby] to come… more happy for [baby] to come than not come…so everybody's been very accommodating.

In addition to childcare, athletes described how support provided for parents by sport organizations is instrumental to athletes’ successful return to sport postpartum. “Amy” shared how her sport organization supported her in bringing her baby to a training camp by covering her parents’ hotel room so they could provide childcare. She explained: The [sport organization] would drive me back to the hotel so I could breastfeed my [baby], or they would give me extra time before games. If I needed to pump, or whatever it was, and they would help me find somewhere to put the milk…. I felt completely and totally supported.

“Cassidy”, on the other hand, was not welcome to stay in the same hotel as her team when she travelled with her baby. She shared: We [my family and I] had to stay at a different hotel, but I'm expected to eat meals with the team… it doesn't help for making me feel welcome.

The need for funding support for postpartum athletes, particularly in terms of childcare, was also described by many of the athletes. “Kara” (31 years) said: It would be ideal if there was some sort of subsidy for [childcare] for athletes. Athletes did highlight that they could access some funds for childcare, but there were inconsistencies in funding available. “Amy” explained: In Olympic years, we get some childcare funding, and in non-Olympic years we do not get any childcare funding. Athletes also described the critical need for funding that would support them in taking time to recover from childbirth and returning to sport. “Robyn” explained: I think that that would be good if our sport policies could mirror our employment policies, and have a little bit of a safety net [i.e., financial support], which it doesn't right now. As stated by “Stella” (38 years): People need a pregnancy card. And quite likely, it's for 2 years for pregnancy and postpartum year, because you can't rush your return. In addition to the “carding” challenges pregnant athletes face, athletes also shared how qualification and ranking processes do not accommodate for pregnant athletes or those returning to sport postpartum. “Kendra” (33 years) explained: I would like to have policies around maternity leave…if I wasn’t ready to come back, our team would have had to forego our spot [at Olympic trials].

3.6 Navigating Motherhood and Sport

Several athletes discussed how the culture in sport is beginning to shift to support women athletes in motherhood. As stated by “Darcy”: I think there was this general idea previously, that's starting to change that once you have a kid you're done in sport, and that the words mom and athlete can't be in the same sentence, which I think is honestly just crap. Because you can totally do both. And we can empower women to do both.

Similarly, “Nicola” explained: These people are in public and they're like, I'm still an athlete. I'm a mom. And so now it's like cool. You can do it; it's cool to be both.

While athletes acknowledged that they can be both an athlete and a mother, they also acknowledged that there are certain expectations that must be met. “Amy” explained: Coaches, management will always support us. And they're always understanding, but at the end of the day, you're still a player on the team. And what's expected of everyone else is the same as what's expected of you. So, you have to be able to do both, you have to be able to balance both and juggle both.

Athletes also explained how their personal expectations had to be modified in order to balance the role of mother and athlete. “Heidi” shared: My expectations are different. Before, I was a lot more selfish, in a productive way. Like I could just set rules… But with kids… they're a higher priority than me in many ways. Some athletes found creative ways to incorporate their training (e.g., running with their child to daycare), while others compared training with their child to bringing their child to work. As “Jana” shared: I remember one of my girlfriends who came back from pregnancy to elite sport. She's like, ‘Listen, I don't [train] with a stroller. That's my job. I don't bring my kid to work every day. You don't bring your kid to work every day. I'm not going to [train] with a stroller.

Participants discussed the importance of having postpartum role models in sport. As “Stella” suggested: I think honestly, there are a lot of role models out there that people see, you know. Like, it's doable, you can do both successfully. Amy shared a message for younger athletes regarding being an athlete and a mother. She said: I think it's important for young female athletes to know that you can do it, that it is doable, but it is hard. But if you put the work in, it's 100% doable.

4 Discussion

High-profile elite athletes such as Alison Felix, Sophie Power and Gwen Jorgensen are proving that childbirth doesn’t have to mean the end of an athletic career. Elite athletes who compete as mothers inspire women and girls to view physical activity and sport as a lifelong endeavour.

The impact of athlete mothers extends throughout society, stimulating discussions of the science and policies around return to sport. We identified an overarching theme that permeated all interviews with athlete-mothers; that is, they described pressures and expectations to return to sport too quickly after childbirth, often against their better judgement and at a detriment to their emotional and physical health.

The 2016 IOC guidelines likened vaginal birth to an acute sport injury, and advocated for increased research to develop return to sport protocols for postpartum [7]. The athletes in our study strongly identified the need for flexible return to sport timelines that would allow them to resume training on their own terms without penalizing their success as an athlete. Fear of losing their position on a team, or not being able to qualify for major competition, drove many athletes to return to sport too soon with many experiencing injuries as a result. Currently, few evidence-informed recommendations on postpartum return to sport exist; there is often a strong reliance on medical clearance at the 6-week postpartum checkup before resuming activity, with little guidance afterwards [26]. In 2019, a group of physiotherapists developed return-to-running guidelines for the postpartum period presenting the first evidence-based framework for health professionals [27, 28]. They highlighted the need to reach specific milestones prior to resuming high-impact/intensity exercise, and provided key considerations about common postpartum complaints including musculoskeletal pain and urinary incontinence. Although these recommendations can be adapted to other modalities, further research and guidance are urgently needed to support return to other sports, which addresses specific contextual factors within each sport, as well as for athletes who train at elite levels.

We and others have previously described that many athletes worry that their decision to become a mother can permanently derail their athletic career [1, 4]. Indeed, our athletes described a wide variety of experiences from personal best performances, to months and years plagued by injury and stress. Athletes identified a lack of awareness of, and access to, physiotherapists specializing in pelvic floor health, lactation consultants to support breastfeeding, and psychologists to support their mental health. The lack of medical resources to support them both physically and mentally was detrimental to their success. Successful return post-pregnancy is greatly influenced by available financial/social supports including childcare and sufficient time to recover from childbirth. The timing and success in returning to elite sport were highly variable and complicated, as athletes had to balance their mental health with high volumes of training and breastfeeding. To complicate their experiences further, athletes had to navigate their own return with a severe lack of evidenced-based return-to-sport protocols. Previous research has documented the critical need for organizational and sponsorship support for elite athlete-mothers [4, 12, 13, 29]. Similarly, athletes in the current study strongly reinforced the critical role that sporting organizations and coaches play in supporting athletes postpartum. Professional organizations such as the Professional Triathlon Organization and Ladies Professional Golf Association have recently developed parental leave policies supporting childcare and maternity leave. In 2018 the Women’s Tennis Association implemented policies on seeding that would ensure that postpartum athletes would not be penalized. Formal protections to support being a mother-athlete are emerging at the professional level, but remain elusive in most other organizations.

The current study complements and builds on previous work exploring the experiences of motherhood of elite athletes returning to sport following childbirth. The progressive, challenging transition from athlete to athlete-mother has been described previously in the literature [3, 13]. Although this dual identify can be complementary [17], it is often fraught with social, cultural and financial challenges. The athletes in our study echoed both the challenges and joy of becoming a mother but also identified key strategies that sporting organizations, coaches and athletes can take to reduce these barriers and facilitate the retention of mothers in elite sport. Clear maternity and family policies are often missing from sport policy [4, 16]. Athletes highlighted the urgent need to develop policies that do not penalize athletes for taking a parental leave. They argued for the critical and urgent need for clear policies on the duration and amount of funding, how pregnancy and parental leave would impact their eligibility and ranking in future competitions, as well as policies and individualized planning for return to training to support athlete wellbeing. Although the need for formal information sources during pregnancy has been previously recognized [4], postpartum athletes identified the lack of evidence-based information guiding return to sport, as well as awareness about the necessity for lactation, pelvic floor health and mental health services specializing in working with elite athletes. Athletes argued for early education about fertility and training to provide a more open and supportive culture that values the contribution of athlete mothers. Based on this work, actionable steps to improve the experiences of athlete mothers have been identified; many of which can be implemented immediately.

We identify several strengths of this study. Although the struggles of elite athlete-mothers have been previously documented in the literature, our participants identified key action items to support a safe and successful return to high-level competition (see Table 2). Our study reported in-depth interviews with elite athletes who had been pregnant in the last 5 years, competing in a wide variety of team and individual sports. We also acknowledge limitations when interpreting the findings of our study. Although we had wide representation across sports, the majority of athletes were from North America; the experiences of athletes in other regions may be different. All but one returned to elite level sport in the postpartum period, thus there was limited representation of individuals who either chose or were not able to return to sport following delivery. Given the voluntary nature of this study, the experiences of athletes who did not return to sport following delivery, or athletes who returned but did not participate in this study, may be different than those who engaged with the interviews.

5 Conclusion

As female athletes extend their athletic careers longer than ever before, sport policy that enables mothers to successfully return to elite sport is paramount and urgently needs to be developed by sporting organizations around the world. Athletes voiced the need to clearly identify maternity leave supports and consequences, as well as education within the organization. High-quality studies are urgently needed to develop individualized return-to-sport protocols to enhance training, reduce injury, and create a less-stressful or uncertain training environment. Inclusion of both quantitative and qualitative studies are necessary to inform practice and adapt to the specific needs of elite-athlete mothers.

References

Davenport MH, Nesdoly A, Ray L, Thornton JS, Khurana R, McHugh TF. Pushing for change: a qualitative study of the experiences of elite athletes during pregnancy. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56(8):452–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104755.

Presidential Task Force on Redefining the Postpartum Visit Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion Number 736. Optimizing postpartum care. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):e140–50.

Massey KL, & Whitehead, A.E. . Pregnancy and motherhood in elite sport: The longitudinal experiences of two elite athletes. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2022;60.

Darroch FEGA, Hillsburg H, McGettigan-Dumas R. Running from responsibility: athletic governing bodies, corporate sponsors, and the failure to support pregnant and postpartum elite female distance runners. Sport Soc. 2019;22(12):2141–60.

Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, Brown W, Davies GAL, Dooley M, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 1—exercise in women planning pregnancy and those who are pregnant. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(10):571–89.

Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, Brown W, Dooley M, Evenson KR, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 2—the effect of exercise on the fetus, labour and birth. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(21):1297–305.

Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, Brown WJ, Davies GAL, Dooley M, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/2017 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 5. Recommendations for health professionals and active women. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(17):1080–5.

Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, Brown WJ, Davies GAL, Dooley M, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3—exercise in the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(21):1516–25.

Bø K, Artal R, Barakat R, Brown WJ, Davies GAL, Dooley M, et al. Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC expert group meeting, Lausanne. Part 4—recommendations for future research. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(24):1724–6.

Kimber ML, Meyer S, McHugh TL, Thornton J, Khurana R, Sivak A, et al. Health outcomes after pregnancy in elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021;53(8):1739–47.

McGannon KR, McMahon J, Gonsalves CA. Juggling motherhood and sport: a qualitative study of the negotiation of competitive recreational athlete mother identities. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2018;36:41–9.

McGannon KR, Tatarnic E, McMahon J. the long and winding road: an autobiographic study of an elite athlete mother’s journey to winning gold. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2019;31(4):385–404.

Tekavc JWP, Cecic ES. Becoming a mother-athlete: female athletes’ transition to motherhood in Slovenia. Sport Soc. 2020;23(4):734–50.

Appleby KM, Fisher LA. Running in and out of motherhood: elite distance runners’ experiences of returning to competition after pregnancy. Women Sport Phys Act J. 2009;18(3–17):3–17.

Giles AR, Phillipps B, Darroch FE, McGettigan-Dumas R. Elite distance runners and breastfeeding: a qualitative study. J Hum Lact. 2016;32:627–32.

Culvin A, Bowes A. The incompatibility of motherhood and professional football in England. Front Sport Act Living. 2021;3:1–13.

Darroch FHH. Keeping pace: mother versus athlete identity among elite long distance runners. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2017;62:61–8.

Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description. Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–40.

Sandelowski M. What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(1):77–84.

McCormack GR NA, Ghoneim D, McHugh TLF. ‘Cul-de-sacs make you fat’: homebuyer and land developer perceptions of neighbourhood walkability, bikeability, livability, vibrancy, and health. Cities Health. 2021.

Larson HKMT, Young BW, Rodgers WM. Pathways from youth to masters swimming: exploring long-term influences of youth swimming experiences. Psycol Sport Exerc. 2019;41:12–20.

McKay AKA, Stellingwerff T, Smith ES, Martin DT, Mujika I, Goosey-Tolfrey VL, et al. Defining training and performance caliber: a participant classification framework. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17(2):317–31.

Karnilowiz W, Ali L, Phillimore J. Community research within a social constructionist epistemology: implications for ‘Scientific Rigor.’ Commun Dev. 2014;45(4):353–67.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Smith B, McGannon KR. Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol. 2018;11:101–21.

Davies GA, Wolfe LA, Mottola MF, MacKinnon C. Joint SOGC/CSEP clinical practice guideline: exercise in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Can J Appl Physiol. 2003;28(3):330–41.

T Goom GD, E Brockwell. Returning to running postnatal—guidelines for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population 2019 2019 [cited; Available from: Returning to running postnatal—guidelines for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population 2019.

Donnelly GM, Moore IS, Brockwell E, Rankin A, Cooke R. Reframing return-to-sport postpartum: the 6 Rs framework. Br J Sports Med. 2022;6(5):244–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2021-104877.

Palmer FRLS. Elite athletes as mothers: managing multiple identities. Sport Manag Rev. 2009;12(4):241–54.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the individuals who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This project was funded by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Development Grant. MHD is supported by the Christenson Professorship in Active Healthy Living and a Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada Joint National and Alberta Improving Heart Health for Women New Investigator award. JT is supported by a Canada Research Chair in Injury Prevention and Physical Activity for Health. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap1 electronic data capture tools hosted and supported by the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute at the University of Alberta.

Conflict of interest

Margie H. Davenport, Lauren Ray, Autumn Nesdoly, Jane Thornton, Rshmi Khurana and Tara-Leigh F. McHugh declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data availability

The generated and analysed data in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Compliance with ethical standards

This study was approved by the University of Alberta Institutional Research Ethics Board (PRO00104326). Participants gave informed consent after reading an information sheet about the study. The study complied with the latest guidelines set out in the Declaration of Helsinki, apart from registration in a publicly accessible database.

Author contributions

MHD, TLM, JT and RK conceived and designed the project. AN and LR conducted the interviews, AN, LR, TLM and MHD analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors interpreted the data, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davenport, M.H., Ray, L., Nesdoly, A. et al. We’re not Superhuman, We’re Human: A Qualitative Description of Elite Athletes’ Experiences of Return to Sport After Childbirth. Sports Med 53, 269–279 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01730-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01730-y