Abstract

Kenya has seen unprecedented declines in fertility from the late 1970s, which stalled during the decade from the mid-1990s, only to resume in the early 2000s when Kenya experienced rapid growth in financial inclusion. In this paper, we do not intend to make causal explanations of these phenomena; instead, we explore what may be sensible to adduce from relationships between fertility and financial inclusion. The Kenyan context presents some unique challenges to establish such connections; regional geographic and ethnic differences, spatial and temporal uneven economic growth, diverse legacies of colonialism, all of which may have affected how fertility trends and financial inclusion activities played out. We find that while modernisation variables such as urbanisation, education, wealth and employment are convincingly related to lower fertility levels, there is little plausible evidence of a role for financial inclusion. More plausible explanations may be found in the country’s colonial history, ethnic identities and post-independence politics.

Résumé

Le Kenya a connu une baisse sans précédent de la fécondité à partir de la fin des années 1970, puis une stagnation d’une décennie à partir du milieu des années 1990. La fécondité a repris au début des années 2000 lorsque le Kenya a connu une croissance rapide de l'inclusion financière. Dans cet article, nous n'avons pas l'intention de fournir d’explications sur les causes de ces phénomènes ; nous explorons plutôt ce qu'il peut être judicieux de déduire sur la question des relations entre la fécondité et l'inclusion financière. Le contexte kenyan présente des défis uniques pour établir de telles connexions ; des disparités géographiques et ethniques régionales, une croissance économique inégale dans l'espace et dans le temps, les divers héritages du colonialisme, qui peuvent tous avoir affecté la façon dont les tendances de la fécondité et les activités d'inclusion financière se sont déroulées. Nous constatons que si des variables de modernisation telles que l'urbanisation, l'éducation, la richesse et l'emploi sont liées de manière convaincante à des niveaux de fécondité plus faibles, il existe peu de preuves plausibles que l'inclusion financière ait joué un tel rôle. L'histoire coloniale du pays, les identités ethniques et la politique post-indépendance fournissent des explications plus plausibles.

Source World Development Indicators, 1960–2017. Notes: A 10-year moving averages trendline for GDP per capita growth in annual % has been added

Source KeDHS, authors estimates. TFR estimated for the previous 15 years unmet need DHS definition estimated with survey weights

Source Authors calculations. WFS, 1977–1978 and KeDHS, 1989–2014, Financial Sector Deepening database

Source Authors calculations. WFS 1977–1978, KeDHS 1989–2014, for the 15 years prior to survey

Source Authors calculations. WFS 1977–1978, KeDHS 1989–2014. Children under 5 mortality rate (U5MR) is used

Source Authors calculations. WFS 1977–1978, KeDHS 1989—2014. Notes: No data for wealth available for 1978

Source Authors calculations using tfr2 from WFS 1977–1978, KeDHS 1989–2014

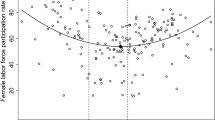

Source Authors calculations. WFS, 1977–1978 and KeDHS, 1989–2014

Source Authors calculations. WFS, 1977–1978 and KeDHS, 1989–2014

Source Authors calculations. WFS 1977–1978, KeDHS 1989–2014

Source Authors calculations. Notes: Orange dotted line = Railways; Red solid line = Boundaries of White Highlands; Black dots = Towns in 1962

Source Financial Sector Deepening database and authors calculations

Source Financial Sector Deepening database and authors calculations

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available at The DHS Program—Data which provides access to unrestricted survey data at no cost upon registration. The FinAccess we draw on is also openly available at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/finaccesshousehold at no cost.

Notes

UN population projections suggest that the population of SSA will be more than twice that of China and other East and South-east Asian countries in 2100 (https://population.un.org/wpp/DataQuery/, accessed 11/3/2020; https://www.economist.com/special-report/2020/03/26/africas-population-will-double-by-2050, accessed 30/3/2020).

E.g. based on experimental or quasi-experimental quantitative analysis (see Deaton and Cartwright 2018 and others).

According to the Polity IV Kenya index (http://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/ken2.htm).

See Duvendack and Palmer-Jones (2017), for a similar argument for Bangladesh.

KeDHS 1989, 1993, 1998, 2003, 2008 & 2014; WFS 1977–1978; Kenya Census 1962 and 1999; FinAccess surveys 2006, 2009, 2013, 2016 and 2018.

The questions on acceptability and decision making are particularly likely to invoke normative responses, and are asked at the same point in the questionnaire; hence it is not surprising that they emerge as factors in principal component analysis, multiple correspondence analysis or factor analysis.

The WFS 1977–1978 does not contain information on which to calculate a wealth index. KeDHS do not report wealth indexes for 1989 to 1998, for which surveys we compute asset indexes based on multiple classification scores (in preference to principal components scores) using the household assets reported in those surveys.

Variables reflecting employment are not well conceptualised in the KeDHS; this is partly because much employment of females is on household or own account farming or gathering, and none of the relevant variables seems to reflect a sharp divide between women predominantly involved in these types of work and those who may be involved in “empowering” types of employment—for wages and or in the formal sector.

Unlike Jedwab et al. (2017), we cannot identify these effects since the data do not allow us to construct a pseudo-panel of fertility by location over an extended period.

We classify the ethnic groups reported in WFS and KeDHS along conventional ethno-linguistic lines distinguishing Bantu (sub-set into the Kikuyu as the nationally most numerous, other Western, and Eastern Bantu, Nilotic (merging Eastern, Southern and Western groups), and Cushitic categories (Greenberg 1948).

Official KeDHS reports of fertility stalling in Kenya only report ethnic differences in desire for more children by ethnic group.

There are insufficient numbers of Cushitic in the surveys up to 2003 for meaningful estimates of fertility.

Quoted in Kokole (1994).

for Kikuyu this variable is 1 between 1963—1978 and 2003—2014, 0 otherwise; for Nilotic it is 1 between 1979 and 2002.

Democracy takes the value 1 1963-1969 and 2003—2014. In both cases 0 otherwise. The regime is classified as autocratic between 1969 and 1992. This periodisation is the same as in Burgess et al. (2015).

It was initially built to provide military access to Lake Victoria, seen as a key to imperial interests; it so happened that the route passed through or near areas which would become of agricultural interest to settlers, partly through deliberate colonial policies aimed to make the railways pay. The thrust of Jedwab et al. (2017) is that towns set up to support and administer first the initial colonial railway and then settler interests had lasting effects on the pattern of urbanisation.

Further results from the authors.

References

Alkire, S., R. Meinzen-Dick, A. Peterman, A.R. Quisumbing, G. Seymour, and A. Vaz. 2012. The women’s empowerment in agriculture index. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2197300.

Alwy, A., and S. Schech. 2004. Ethnic inequalities in education in Kenya. International Education Journal 5 (2): 266.

Amin, R., R.B. Hill, and Y. Li. 1995. Poor women’s participation in credit-based self-employment: The impact on their empowerment, fertility, contraceptive use, and fertility desire in rural Bangladesh. The Pakistan Development Review 34: 93–119.

Amin, R., Y. Li, and A.U. Ahmed. 1996. Women’s credit programs and family planning in rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives 1: 158–162.

Askew, I., Ezeh, A. C., Bongaarts, J., & Townsend, J. 2009. Kenya's Fertility Transition: Trends, determinants and implications for policy and programmes. Available at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2158&context=departments_sbsr-rh.

Askew, I., N. Maggwa, and F. Obare. 2017. Fertility transitions in Ghana and Kenya: Trends, determinants, and implications for policy and programs. Population and Development Review 43: 289–307.

Balbo, N., F.C. Billari, and M. Mills. 2013. Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population/revue Européenne De Démographie 29 (1): 1–38.

Balk, D. 1994. Individual and community aspects of women’s status and fertility in rural Bangladesh. Population Studies 48: 21–45.

Basu, A.M. 1996. Women's education, marriage and fertility: Do men really not matter? (No. 96). Cornell University, Population and Development Program.

Bauni, E., W. Gichuhi, and S. Wasao. 1999. Ethnicity and fertility in Kenya. https://www.popline.org/node/534282.

Basu, A.M., and G.B. Koolwal. 2005. Two concepts of female empowerment—Some leads from DHS data on women’s status and reproductive health. In A focus on gender—Collected papers on gender using DHS data, ed. S. Kishore, 15–33. Calverton: ORC Macro.

Berman, B.J. 1998. Ethnicity, patronage and the African state: The politics of uncivil nationalism. African Affairs 97 (388): 305–341.

Berman, B.J., J. Cottrell, and Y. Ghai. 2009. Patrons, clients, and constitutions: Ethnic politics and political reform in Kenya. Canadian Journal of African Studies/la Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 43 (3): 462–506.

Bernhardt, E.M. 1993. Fertility and employment. European Sociological Review 9 (1): 25–42.

Bongaarts, J., O. Frank, and R. Lesthaeghe. 1984. The proximate determinants of fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review, 511–537.

Bongaarts, J. 1978. A framework for analyzing the proximate determinants of fertility. Population and Development Review 105–132.

Bongaarts, J. 2008. Fertility transitions in developing countries: Progress or stagnation? Studies in Family Planning 39 (2): 105–110.

Bongaarts, J. 2017. Africa’s unique fertility transition. Population and Development Review 43 (S1): 39–58.

Booth, A., and D. Duvall. 1981. Sex roles and the link between fertility and employment. Sex Roles 7 (8): 847–856.

Burgess, R., R. Jedwab, E. Miguel, A. Morjaria, and Padró i Miquel, G. 2015. The value of democracy: Evidence from road building in Kenya. American Economic Review 105 (6): 1817–1851.

Caldwell, J.C., and P. Caldwell. 1987. The cultural context of high fertility in sub-Saharan Africa. Population and Development Review 409–437.

Carter, M.W. 2002. “Because he loves me”: Husbands’ involvement in maternal health in Guatemala. Culture, Health & Sexuality 4: 259–279.

Cheeseman, N., K. Kanyinga, G. Lynch, M. Ruteere, and J. Willis. 2019. Kenya’s 2017 elections: Winner-takes-all politics as usual? Journal of Eastern African Studies 13 (2): 215–234.

Cleland, J., S. Bernstein, A. Ezeh, A. Faundes, A. Glasier, and J. Innis. 2006. Family Planning: The Unfinished Agenda. The Lancet 368 (9549): 1810–1827.

Constantine, C. 2017. Economic structures, institutions and economic performance. Journal of Economic Structures 6 (1): 2.

Crichton, J. 2008. Changing fortunes: Analysis of fluctuating policy space for family planning in Kenya. Health Policy and Planning 23 (5): 339–350.

Cruz, M., and S.A. Ahmed. 2018. On the impact of demographic change on economic growth and poverty. World Development 105: 95–106.

Davis, K., and J. Blake. 1956. Social structure and fertility: An analytic framework. Economic Development and Cultural Change 4 (3): 211–235.

Deaton, A., and N. Cartwright. 2018. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine 210: 2–21.

Desai, J., and A. Tarozzi. 2011. Microcredit, family planning programs, and contraceptive behavior: Evidence from a field experiment in Ethiopia. Demography 48 (2): 749.

Duvendack, M., and P. Mader. 2020. Impact of financial inclusion in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review of reviews. Journal of Economic Surveys 34 (3): 594–593.

Duvendack, M., and R. Palmer-Jones. 2017. Micro-finance, women’s empowerment and fertility decline in Bangladesh: How important was women’s agency? The Journal of Development Studies 53 (5): 664–683.

Easterly, W., and R. Levine. 1997. Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1203–1250.

Ewerling, F., J.W. Lynch, C.G. Victora, A. van Eerdewijk, M. Tyszler, and A.J. Barros. 2017. The SWPER index for women’s empowerment in Africa: Development and validation of an index based on survey data. The Lancet Global Health 5 (9): e916–e923.

Franck, R., and I. Rainer. 2012. Does the leader’s ethnicity matter? Ethnic favoritism, education, and health in sub-Saharan Africa. American Political Science Review 106 (2): 294–325.

FSD Kenya, Central Bank of Kenya & Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. 2019. FinAccess household survey on financial inclusion. Nairobi: FSD Kenya, Central Bank of Kenya and Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Gibbon, P. 1992. A failed agenda? African agriculture under structural adjustment with special reference to Kenya and Ghana. The Journal of Peasant Studies 20 (1): 50–96.

Goliber, T.J. 1985. Sub-Saharan Africa: Population pressures on development. Population Bulletin 40 (1): 1.

Greenberg, J.H. 1948. Linguistics and ethnology. Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 4 (2): 140–147.

Hartmann, B. 1995. Reproductive rights and wrongs: The global politics of population control. South End Press.

Hulme, D., J. Kashangaki, and H. Mugwanga. 1999. Dropouts amongst Kenyan Microfinance Institutions. MicroSave Research Paper. http://www.microsave.org/relateddownloads.asp.

International Labour Office. 1972. Employment, incomes and equality: a strategy for increasing productive employment in Kenya. International Labour Office.

Iyer, S., and M. Weeks. 2009. Social interactions, ethnicity and fertility in Kenya. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/229439/0903.pdf?sequence=2.

Jedwab, R., E. Kerby, and A. Moradi. 2017. History, path dependence and development: Evidence from colonial railways, settlers and cities in Kenya. The Economic Journal 127 (603): 1467–1494.

Kebede, E., A. Goujon, and W. Lutz. 2019. Stalls in Africa’s fertility decline partly result from disruptions in female education. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116 (8): 2891–2896.

Khadiagala, G.M. 2010. Political movements and coalition politics in Kenya: Entrenching ethnicity. South African Journal of International Affairs 17 (1): 65–84.

Kim, J.C., C.H. Watts, J.R. Hargreaves, L.X. Ndhlovu, G. Phetla, L.A. Morison, et al. 2007. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. American Journal of Public Health 97 (10): 1794–1802.

Kishore, S. (Ed.). 2005. A focus on gender: Collected papers on gender using DHS data. Claverton, MD: ORC Macro.

Kokole, O.H. 1994. The politics of fertility in Africa. Population and Development Review 20: 73–88.

Kramon, E., and D.N. Posner. 2016. Ethnic favoritism in education in Kenya. Quarterly Journal of Political Science 11 (1): 1–58.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de-Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1999. The quality of government. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15 (1): 222–279.

Leatherman, S., M. Metcalfe, K. Geissler, and C. Dunford. 2012. Integrating microfinance and health strategies: Examining the evidence to inform policy and practice. Health Policy and Planning 27 (2): 85–101.

Lloyd, C.B. 1991. The contribution of the World Fertility Surveys to an understanding of the relationship between women’s work and fertility. Studies in Family Planning 22 (3): 144–161.

Lundberg, S., and R.A. Pollak. 1993. Separate spheres bargaining and the marriage market. Journal of Political Economy 101 (6): 988–1010.

Mackie, J.L. 1965. Causes and conditions. American Philosophical Quarterly 2 (4): 245–264.

Maseland, R. 2018. Is colonialism history? The declining impact of colonial legacies on African institutional and economic development. Journal of Institutional Economics 14 (2): 259–287.

Michalopoulos, S., and E. Papaioannou. 2013. Pre-colonial ethnic institutions and contemporary African development. Econometrica 81 (1): 113–152.

Michalopoulos, S., and E. Papaioannou. 2020. Historical legacies and African development. Journal of Economic Literature 58 (1): 53–128.

Moultrie, T.A., R.E. Dorrington, A.G. Hill, K. Hill, I.M. Timæus, and B. Zaba. 2013. Tools for demographic estimation. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

Mulli, L. 1999. Understanding election clashes in Kenya, 1992 and 1997. African Security Studies 8 (4): 75–80.

Nunn, N. 2010. Religious conversion in colonial Africa. American Economic Review 100 (2): 147–152.

Nunn, N. (2014). Historical development. In Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 2, pp. 347–402). New York: Elsevier

O’Brien, F.A., and T.C.I. Ryan. 2001. Aid and reform in Africa: Kenya case study. In Aid and reform in Africa: Lessons from ten case studies, ed. S. Devarajan, D. Dollar, and T. Holmgren, 469–532. Washington: World Bank.

Odwe, G. O. (2015). Fertility and household poverty in Kenya: A comparative analysis of Coast and Western Provinces. African Population Studies 29(2).

Oyugi, W. O. 1997. Ethnicity in the electoral process: The 1992 general elections in Kenya. African Journal of Political Science/Revue Africaine de Science Politique 41–69.

Ravallion, M. 2001. Growth, inequality and poverty: Looking beyond averages. World Development 29 (11): 1803–1815.

Schatz, E., and J. Williams. 2012. Measuring gender and reproductive health in africa using demographic and health surveys: The need for mixed-methods research. Culture, Health & Sexuality 14: 811–826.

Schoumaker, B. 2011, March 31–April 2. Omissions of births in DHS birth histories in Sub-Saharan Africa: Measurement and determinants. Paper presented at PAA, Washington, DC.

Schoumaker, B. 2019. Stalls in fertility transitions in sub-Saharan Africa: Revisiting the evidence. Studies in Family Planning 50 (3): 257–278.

Schuler, S.R., S.M. Hashemi, and A.P. Riley. 1997. The influence of women’s changing roles and status in Bangladesh’s fertility transition: Evidence from a study of credit programs and contraceptive use. World Development 25: 563–575.

Shipton, P. M. (2010). Credit between cultures: Credit between cultures: Farmers, financiers, and misunderstanding in Africa. Yale University Press.

Sinding, S. W., Ross, J. A., & Rosenfield, A. G. (1994). Seeking common ground: Unmet need and demographic goals. International Family Planning Perspectives, 23–32.

Sobotka, T., V. Skirbekk, and D. Philipov. 2011. Economic recession and fertility in the developed world. Population and Development Review 37 (2): 267–306.

Spolare, E., and R. Wacziarg. 2013. How deep are the roots of economic development? Journal of Economic Literature 51 (2): 325–369.

Stewart, R., C. van Rooyen, K. Dickson, M. Majoro, and T. de Wet. 2010. What is the impact of microfinance on poor people? A Systematic Review of Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. Technical Report, EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, University of London.

Story, W.T., and S. Burgard. 2012. Couples’ reports of household decision-making and the utilization of maternal health services in Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine 75: 2403–2411.

Suri, T., and W. Jack. 2016. The long-run poverty and gender impacts of mobile money. Science 354 (6317): 1288–1292.

Thurston, A. 1987. Smallholder agriculture in Colonial Kenya: The official mind and the swynnerton plan. Cambridge African Monographs 8. Cambridge, Cambridgeshire: African Studies Centre.

Tyce, M. 2018. The political dynamics of growth and structural transformation in Kenya: exploring the role of state-business relations (Doctoral dissertation, University of Manchester).

Upadhyay, U.D., and D. Karasek. 2010. Women’s empowerment and achievement of desired fertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. USAID, DHS Working Paper No. 80.

Upadhyay, U.D., J.D. Gipson, M. Withers, S. Lewis, E.J. Ciaraldi, A. Fraser, et al. 2014. Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine 115: 111–120.

Vogt, M., N.C. Bormann, S. Rüegger, L.E. Cederman, P. Hunziker, and L. Girardin. 2015. Integrating data on ethnicity, geography, and conflict: The ethnic power relations data set family. Journal of Conflict Resolution 59 (7): 1327–1342.

Weinreb, A.A. 2001. First politics, then culture: Accounting for ethnic differences in demographic behavior in Kenya. Population and Development Review 27 (3): 437–467.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge, without implication, funding by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) under a research grant, ESRC Reference: ES/N013344/2, on ‘Delivering inclusive financial development and growth’.

Funding

Funding was provided by ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, University of Southampton (ES/N013344/2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duvendack, M., Palmer-Jones, R. Colonial Legacies, Ethnicity and Fertility Decline in Kenya: What has Financial Inclusion Got to Do with It?. Eur J Dev Res 35, 1028–1058 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00557-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-022-00557-7