Abstract

Purpose of Review

This review aims to identify the evidence for the assessment of the effectiveness and feasibility of multi-sectoral climate adaptation for food security and malnutrition. This review and the assessments of the evidence inform the contents and confidence statements in section “multi-sectoral adaptation for malnutrition” and in the Executive Summary of the IPCC AR6 WGII Chapter 7: Health Wellbeing and Changing Community Structure.

Recent Findings

A review of adaptation for food security and nutrition FSN in West Africa concluded that food security and nutrition and climate adaptation are not independent goals, but often go under different sectors.

Summary

Most of the adaptation categories identified here are highly effective in reducing climate risks to food security and malnutrition, and the implementation is moderately or highly feasible. Categories include improved access to (1) sustainable, affordable, and healthy diets from climate-resilient, nutrition-sensitive agroecological food systems; (ii) health care (including child, maternal, and reproductive), nutrition services, water and sanitation; (iii) anticipatory actions, adoption of the IPC classification, EW-EA systems; and (iv) nutrition-sensitive adaptive social protection. Risk reduction, such as weather-related insurance, and risk management are moderately effective and feasible due to economic and institutional barriers. Women and girls’ empowerment, enhanced education, rights-based approaches, and peace building are highly relevant enablers for implementation of the adaptation options.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change and variability have, and will further have, significant impacts on food systems, food security, and nutrition, threatening the efforts to end malnutrition in all its forms, and achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 1, 2, and 3 [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Unsustainable food systems and increasing global demand of high calorie unhealthy foods and animal products are the main contributors to climate change (21–37% of total Green House Gas (GHG) emissions), environmental degradation, and contribute to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) [1, 6,7,8,9]. Imbalanced diets, low in fruits and vegetables, and high in salt, sugar, and red and processed meat, are the number one risk factor for mortality globally [10]. About a third of the National Food Based Dietary Guidelines (FBDG) worldwide are incompatible with the agenda on non-communicable diseases, and most of national FBDG are incompatible with the Paris Climate Agreement and other environmental targets [11].

Globally, more than 820 million people remain undernourished, 149 million children are stunted, 49.5 million children are wasted, and more than 2 billion people are micronutrient deficient [12]. More than 3.1 million child and maternal deaths annually are attributed to undernutrition (nearly half of all deaths in children under 5 are attribute to undernutrition) [13]. In addition to be the single main cause of mortality and disease, undernutrition in the first 1000 days of a child’s life can lead to stunted growth, resulting in impaired cognitive ability and reduced school and work performance in the future. The associated costs of stunting in terms of lost economic growth can be of the order of 10% of GDP per year in Africa [14]. At the same time, the prevalence of diseases associated with high-calorie, imbalanced diets is increasing globally, with 40.1 million under 5 children overweight [12] and 2.1 billion adults overweight or obese [7]. Climate change and variability, and their impacts in the form of more frequent and intense extreme climate events, are further threatening the efforts to end malnutrition in all its forms [2, 4].

The UN System Standing Committee on Nutrition has, for more than 10 years, been providing evidence of the urgency and benefits of investing in the integration of nutrition-sensitive solutions in the National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR), and in the National Determined Contributions (NDCs), in order to protect the lives of the most vulnerable [15, 16]. Despite this, adaptation solutions for malnutrition have been basically absent in both—the health and food security sections—of the National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs), and the NAPs of Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and Low-Income Countries (LIC) affected by hunger and severe nutritional problems.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 5th Assessment Report and the IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification and Land, assessed the impacts of climate change on food security and nutritional outcomes [2, 17]. However, these reports did not assess the existing evidence of multisectoral adaptation options to prevent climate impacts in malnutrition in all its forms, or to anticipate climate-related food emergencies which result in millions of people in several LDCs and LICs experiencing acute food insecurity and malnutrition, at the same time. This was reported during the last ENSO events 2014–2016 in Central America, and in Eastern and Southern Africa 2015–2017 [18, 21].

This paper will present the review of the evidence that inform the content and confidence statements of the section “multi-sectoral adaptation for malnutrition” and of the Executive Summary of the IPCC AR6 WGII Chapter 7: Health Wellbeing and the changing structure of communities. We review and identify effective multi-sectoral climate adaptation strategies and options for FSN and malnutrition in all its forms, and key cross-cutting adaptation enablers [22]. To increase the policy relevance of the results, we then present a feasibility and effectiveness assessment of these multi-sectoral climate adaptations across systems including food, health, water and sanitation, and social protection. Finally, we assess the relevance of cross-cutting enablers of climate adaptation for FSN and malnutrition, and the timeframe for implementation of coordinated adaptation actions to build climate and human resilience.

Methodology

Identification of Climate Risks

The identification of the severe climate risks for food security and nutrition for which the feasibility and effectiveness of the corresponding adaption options were assessed was informed by (1) national data on the observed impacts of climate extreme events on acute food insecurity and acute malnutrition compiled in the annual Global Reports on Food Crises [18,19,20,21, 23] and by (2) the evidence on the literature of the climate change risks on malnutrition in all its forms presented in Table 2 (see below).

Review of Evidence of Multi-Sectoral Adaptation for Food Security and Malnutrition in All its Forms and Key Cross-Cutting Adaptation Enablers

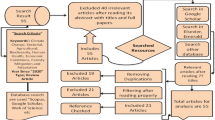

The review undertaken to identify the papers for this assessment is considered a rapid review [24, 25]. This is a method increasingly used by policy makers in order to inform decision-making [26]. Rapid reviews follow the principles of systematic reviews; however, these are undertaken in short periods [27]. For this research, the rapid review followed three steps: (i) agreed use of definitions and identification searching terms for climate change adaptation for food security and nutrition and key enablers; (ii) literature search in Scopus and Web of Science and Google Scholar published between 2014 and 2020 in English, plus relevant gray literature, such as United Nations and World Bank Reports; and (iii) the screening and content appraisal, cross-checking of references to include adaptation measures for food and nutrition and key enablers was done as an expert assessment.

The Food Security and Malnutrition terms and definitions used in this paper are internationally agreed, and several of them are key indicators from the SDG2 (Ending Hunger). Food Security is a state that prevails when people at all times have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious, and culturally appropriate food for normal growth and development, and an active and healthy life [9]. Malnutrition is a broad term that refers to all forms of poor nutrition, and it includes undernutrition as well as overweight and obesity. Malnutrition is caused by a complex array of factors, including dietary inadequacy (deficiencies, excesses, or imbalances in energy, protein, and micronutrients), infections, and sociocultural factors [28]. Undernutrition exists when a combination of insufficient food intake, health, and care conditions results in one or more of the following: underweight for age, short for age (stunted), thin for height (wasted), or functionally deficient in vitamins and/or minerals (micronutrient malnutrition) [9]. Under-nourishment (or hunger) is defined as the condition in which an individual’s habitual food consumption is insufficient to provide the amount of dietary energy required to maintain a normal, active, and healthy life [28]. Prevalence of undernourishment [29] is a complex, aggregated measure of undernourishment at national level.

Acute Food Insecurity is any manifestation of food insecurity at a specific point in time of a severity that threatens human lives, livelihoods, or both, regardless of the causes, context, or duration [30]. This indicator is measured by the IPC (Integrated Food Security Phase Classification) Consortium,which serves as a global reference for the classification of acute food insecurity and acute malnutrition [31].

Selection of the Literature on Climate Change Adaptation for Food Security and Nutrition and Cross-Cutting Adaptation Enablers

Based on literature reviewed, and the existing reports of the UN System Standing Committee on Nutrition (UN SCN) and the World Bank, effective multi-sectoral adaptation options for food security and nutrition across systems include nutrition-sensitive food production; access to healthy-diverse-affordable diets from sustainable food systems; nutrition-sensitive social protection; access to health (including child, maternal, and reproductive health); access to nutrition services; water and sanitation; adoption of early warning systems; and nutrition-sensitive risk reduction, risk transfer, risk sharing, and risk management [15, 32,33,34,35,36]. Common enablers across adaptation actions include education, women’s and girls’ empowerment, rights-based governance, and peace-building initiatives [15, 21, 33, 37,38,39,40].

Articles were selected via cross-referencing and expert consultation. Articles were considered relevant if they explicitly identified multisectoral climate adaptation options related to food security and nutrition (FSN) and/or cross-sectoral enablers focused on education, women’s and girls’ empowerment, peace building, or rights-based approaches. Identified papers were screened with the following inclusion criteria: (a) case studies, empirical research, scenario-modeling studies; (b) multi-sectoral climate change adaptation for FSN; and (c) cross-sectoral enablers: education, women’s empowerment, rights-based approaches, and peace building. We identified 80 papers that featured case studies, empirical research, or scenarios of frequently used climate adaptation for FSN, including cross-cutting adaptation enablers. Of particular interest for this assessment was to include case studies showcasing the effectiveness of combined and/or integrated multisectoral approaches (e.g., integrating Climate or WASH in nutrition programing). The UN World Food Program (WFP) facilitated case studies of coordinated multisectoral climate adaptation for food security and malnutrition in East Africa, Middle East, and Central America.

Assessing Effectiveness and Feasibility of Adaptation Options

The feasibility assessment was introduced in the IPCC Special Report on 1.5 °C (SR1.5) responding to a request made by member states, regarding which adaptation options are more feasible compared to others. The methodology used to carry out this feasibility assessment is adapted from the IPCC Special Report on 1.5 °C [41], de Conick et al. [42], and Singh et al. [43].

Effectiveness

of an adaptation option can be interpreted differently depending on the purpose of the adaptation. In this assessment, we used the risk mitigation potential definition, which refers to the degree the adaptation option can reduce the likelihood and/or consequences of a particular risk [42, 43], in this case, climate change risks to food security and nutrition (Appendix SR1.5). Effectiveness is determined by comparing it against a baseline damage to determine the damage reduction potential.

Three levels of effectiveness determined in the context of this assessment are:

-

High (> 75% of a baseline damage level)

-

Medium (25–75% of a baseline damage level)

-

Low (< 25% of a baseline damage level)

Feasibility

was defined as how significant the barriers reported in the literature are to implementing a particular adaptation option.

-

Highly feasible options are those where no or very few barriers are reported (and had an average score > 2.5 on the scoring criteria).

-

Moderately feasible are those where barriers exist but do not have a strong negative effect on the adaptation option or evidence is mixed (it scores between 2.5 and 1.5).

-

Low feasibility options have multiple barriers reported that could block the adaptation option (and score below 1.5 on the criteria used).

Six dimensions of feasibility (economic, technical, social, institutional, environmental, and geophysical) have been considered per each adaptation category, using nineteen indicators according to the feasibility assessment presented in the appendix of the IPCC SR1.5 Chapter 4, (see Table 1) [41]. An extraction table with these dimensions and indicators has been used to extract and compile the relevant information from the 80 papers selected, for the assessment of feasibility and effectiveness of the adaptation options (including evidence and agreement) and the cross-sectoral enablers (see Table 4).

The feasibility and effectiveness assessment covers six categories of multi-sectoral adaptation options for food security and nutrition, and in particular to malnutrition in all its forms (due to decline in food availability and nutritional quality and increased cost of healthy food, see Table 3). Cross-cutting enablers across adaptation actions include education, women’s and girls’ empowerment, rights-based governance, and peace-building initiatives. Timeframe for implementation has also been assessed when evidence was available (e.g., urgent, short term, and medium term/longer term).

The references used for the feasibility and effectiveness’ assessment are in Table 3. The selected papers were assessed by experts who allocated the final score for each indicator and the dimensions. Once all the indicators for each dimension were identified, the weighting procedure from SR15 was used to aggregate the indicators into the dimensions’ averages [43].

Evidence is defined here as the degree of evidence that reflects the amount, quality, and consistency of scientific/technical information. Agreement refers here to the degree of agreement within the scientific body of knowledge, on a particular finding. It is assessed based on multiple lines of evidence (e.g., mechanistic, theory, data, models, expert judgment) and expressed qualitatively.

Strengths and Limitations of the Methodology for Assessing Feasibility of Adaptation Options

Some of the main strengths of this methodology for assessing feasibility of adaptation options are that it is comprehensive, traceable, and transparent and it can greatly increase the policy relevance of the results. Feasibility and effectiveness were assessed using a very detailed indicator subset. Limitations are related to inability to carry out a full systematic review, due to the substantial time and resource required to do such assessments. Some indicators may not be relevant for the selected adaptation options, and it is possible that not all issues are captured by the set of indicators used. There are opportunities to have a regional/economic breakdown, and to include trade-offs.

Results

Climate Change Impacts and Risks to Food Security and Nutrition

Climate change affects all the dimensions of food security: food production and availability, stability of food supplies, access to food, and food utilization [2]. Declining food availability caused by climate change is likely to increase food costs, impacting consumers globally by reducing purchasing power, with low-income consumers particularly at risk from hunger [4, 44, 45]. Higher prices depress consumer demand, reducing energy intake (calories) globally, leading to less healthy diets, potentially with lower availability of key micronutrients in foods [3, 5, 45] and increasing diet-related mortality in low and middle-income countries [1, 6, 9]. Climate change and variability impact the main underlying causes of maternal and child malnutrition and disease, including household food security; dietary diversity; nutrient quality; water quality; and access to maternal, reproductive, and child health, leading to disease and child stunting [33]. Climate extreme events impact the socio-economic factors that determine food security and nutrition, such as livelihoods, assets, income, food aid, resources, infrastructure (e.g., hospitals, sanitation) resources, and political structures [16].

Extreme climate events have been the main drivers of the observed acute food insecurity and malnutrition (measured as IPC|CH Acute Food Insecurity Phase 3 Crisis or above.) of an estimated 166 million people in 31 countries who required humanitarian assistance due to climate-related food emergencies between 2015 and 2019 (45.1 million people in the Horn of Africa, 62 million in Eastern and Southern Africa, and 13.2 million in the Dry Corridor of Central America) [18,19,20,21, 23]. Between 2015 and 2017, El Nino–driven droughts and floods were the main cause of food emergencies in 26 countries, driving 103 millions of people in IPC|CH Acute Food Insecurity Phase 3 Crisis or above, and requiring humanitarian assistance to survive (40.5 million people in the Horn of Africa, 28.9 million in Eastern and Southern Africa, and 7.2 million in the Dry Corridor of Central America) [18,19,20,21, 23].

Projected climate risks on malnutrition in all its forms are linked to the decline in food availability and nutritional quality, and increased cost of healthy food resulting in three main risks: (i) reduced energy intake (measured as calories), (ii) decreased availability of fruits and vegetables, and (iii) lower micronutrients availability in main staple foods, fruits, and vegetables due to excessive CO2 in the atmosphere [3, 5] (see Table 2).

Multisectoral and Multi-System Adaptation for Food Security and Nutrition

The protection of nutrition under climate change requires multi-sectoral adaptation actions across sectors and systems: the food system, social protection systems, health system (Swinburn et al. 2019), water and sanitation systems, early warning systems, and risk reduction and risk management. Within the efforts of climate-resilient development, a combination of healthy and affordable diets from sustainable food systems improved access to health, nutrition, water and social protection, community-based risk reduction, and institutional cross-sectoral collaboration which have been identified as a means to address the impacts of climate change to food security and nutrition [2, 9, 33, 34]. Six adaptation categories and four cross-cutting adaptation enabling factors have been considered in the feasibility and effectiveness’ assessment of multisectoral climate adaptation for nutrition (Tables 3 and 4). Each option is explained in detail in the following sections.

Climate-Resilient, Nutrition-Sensitive, and Agroecological Food Systems

Nutrition-sensitive and climate-resilient sustainable food production systems, including agroecological approaches and indigenous food systems (such as nomadic pastoralists and artisanal fisher folks), are part of food system adaptation solutions. To be sustainable, these adaptation strategies must be suitable for the local needs, agroecosystem, microclimate, and socio-cultural contexts. Adaptation strategies need to address social inequities such as gender, race, or class to be nutrition-sensitive and climate-resilient [37, 112, 113]. As part of the climate adaptation process, countries need to enhance agricultural food production’s nutritional quality and dietary diversity for local consumption. In this context, biodiversity of food systems is considered a lynchpin of sustainable food systems, as it increases resilience [114,115,116]. Agroecological practices by small and mid-sized family farms offer opportunities to increase dietary diversity at the household level while building climate-related local resilience to food insecurity [53, 117, 118]. Integrated agroecological systems bring the synergies of mixed crop-livestock-fisheries and agroforestry systems to reduce waste and expenses on agricultural inputs and increase food production diversity [53, 119]. Those synergies, alongside increased biodiversity, enhancing beneficial ecological interactions, recycling of biomass, and a lesser dependence on external inputs (e.g., oil-based or commercial inputs), render these agroecological systems more resilient to climate shocks, especially when gender equity and social justice are integrated into the equation [49, 53, 55, 120,121,122]. Agroecological systems also draw on indigenous, local knowledge, farmer-to-farmer learning, and experimentation and encourage collective, democratic, and inclusive governance of food systems [53, 123]. Agroecological practices, either customary or new innovations, are sustained by a different valuation of food as a common, public good and human rights [124]. Participatory, peer-based education methods [125, 126]; communication for development; and social marketing strategies that strengthen local and regional food systems and promote diverse cultivation and consumption of local micronutrient-rich foods can also bolster nutrition and food security [69, 127, 128]. Addressing gender and other social inequities may be crucial if these programs are to be effective [129, 130].

Access to Sustainable, Diverse, Healthy, and Affordable Diets

Diverse, plant-rich diets, in line with WHO recommendations on healthy eating, could reduce global mortality by 6‒10% and food-related GHG emissions by 29‒70% compared with a reference scenario for 2050 [1]. A transformation into healthy dietary habits by 2050 would require substantial dietary shifts, including a greater than 50% reduction in global consumption of red meat and sugar, and more than doubling the consumption of healthy foods, such as nuts, fruits, vegetables, and legumes [8]. Transitioning towards healthy diets in line with the planetary diet could prevent up to 11.1 million deaths per year in 2030, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) from food production and consumption worldwide by up to 80% [8]. The necessary shifts into healthy diets differ regionally and by country [60], and the impacts of dietary transitions should be considered in climate change mitigation policy [131]. A trade-off of the planetary diet is that it exceeded the income of more than 1.6 billion people worldwide [132]. Adopting the EAT-Lancet planetary health diet, using current food production methods, would reduce GHGE in 101 countries and it would increase in 36 countries [131]. Transformative approaches towards healthy, sustainable, plant-rich diets require policies for the production of more fruits, vegetables, and pulses, by diverting subsidies from the cash crops that are the basis of ultra-processed foods (such as corn, soybean, and palm oil) to fruits, vegetables, and pulses. These policies can be supported by public education, inclusion of sustainability criteria in national Food Based Dietary Guidelines, promoting traditional/indigenous diets, and labeling and establishing healthy and sustainable institutional food procurement for School Feeding Programs among others [7, 8, 16, 133,134,135,136].

Access to Health, Nutrition Services, and Water and Sanitation

Access to universal health, including maternal and child care, reproductive health, family planning, nutrition services, safe food, access to water and sanitation, clean cookstoves, and healthy environments and education, contributes to reducing vulnerability and building resilience to the impacts of climate change and variability in malnutrition in all its forms [33, 64, 67, 68, 82, 137]. Building resilience in communities severely affected by climate-related extreme events and food crisis (i.e., IPC acute food insecurity Phase 3 or more) requires a two-pronged approach, consisting in an urgent and short-term response to prevent the threat and prevent acute malnutrition and mortality, and a medium to long-term nutrition-sensitive multi-sectoral adaptation approach. The first urgent response to climate-related extreme events consists in immediate food assistance, safety nets, and direct nutrition interventions to treat the severe impacts in acute food insecurity and malnutrition and save lives. The adoption of IPC indicator of acute food insecurity is critical to plan the humanitarian assistance needs. The prevention or treatment of moderate undernutrition and the treatment of severe undernutrition (i.e., acute malnutrition) with ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF) are frequently required to save children’s lives. Food assistance needs to be targeted directly to meet immediate FSN requirements of vulnerable groups, to increase their productive potential and adaptive capacity, and to protect them from climate-related disasters. Food assistance can be delivered, for example, by the provision of school meals, labor-based safety nets, or cash-based interventions, such as vouchers. Direct nutrition interventions that can build resilience overtime to the impacts of climate change on children and maternal undernutrition include a set of highly cost-effective, evidence-based interventions for children under 2 years old, such as exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months; complementary feeding for infants over 6 months of age; improved hygiene, including handwashing and deworming programs; micronutrient supplementation for young children and their mothers (e.g., periodic vitamin A supplements and therapeutic Zinc supplements for diarrhea management); and provision of micronutrients through food fortification for all (e.g., salt iodization, iron fortification) [32, 35, 70]. Recurrent and more intense droughts and floods can result in the contamination of drinking water and poor sanitation and hygiene. Integrating water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) into nutrition programs is critical to decrease undernutrition and address the needs among the very poor and vulnerable populations [36]. A second broader medium-longer-term approach aims to counter the drivers of malnutrition by scaling up integrated responses guided by inter-sector analysis of multiple vulnerabilities such as related to improved EW-EA anticipatory systems, access to water and sanitation systems, healthcare, nutrition-sensitive agriculture, adaptive social protection, and enhancing disaster risk reduction and risk management [2, 33, 34].

Nutrition-Sensitive and Shock-Responsive Adaptive Social Protection

Social protection mechanisms typically entail cash or food transfers to households or individuals that meet a particular vulnerability threshold, such as food insecurity and malnutrition [138]. Common instruments include unconditional cash transfers or public work programs (food-for-work or cash-for-work), or extension of credit and insurance services. The use of conditional cash and asset transfers has been shown to reduce impacts of extreme climate events [77]. Short-term emergency or seasonal safety nets avoid impacts and irreversible losses in human capital, reduce the incidence of negative coping mechanisms, and protect the family’s access to sufficient, nutritious, and safe food [35]. Shock-responsive social protection schemes focus on large-scale shocks that affect a large proportion of the population simultaneously. Nutrition-sensitive social protection, such as school feeding programs, contributes to build resilience to the impacts of climate change, facilitating access to healthy diets. School feeding programs improve nutritional and health outcomes, especially among girls, by promoting education and reducing child pregnancy and fertility rates [67]. Children from families participating in Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program have improved nutritional outcomes, partly due to better household food consumption patterns and reduced child labor [139]. Social protection can enhance livelihoods in the face of long-term climate change, especially if the program engages the beneficiaries in communal public works that foster resilience (such as water catchment technologies to address drought risk, slope protection barriers, or micro-dams) or if they engage in behavior that increases adaptive capacity such as reducing the production of water-intensive crops [74]. Adaptive social protection programs that combine social protection, disaster risk reduction, and climate adaptation objectives in an integrated program are more likely to foster preventive and longer-term adaptive and/or transformational interventions to address climate risks than schemes focusing on social protection and disaster risk reduction alone [140, 141].

Early Warning-Early Action Systems to Prevent Acute Food Insecurity/Malnutrition

Anticipatory options, such as Early Warning-Early Action (EW-EA) systems for FSN, such as the USAID Famine Early Warning System (FEWS NET), FAO’s Global Information, and Early Warning Systems (GIEWS), and WFP’s Corporate Alert System, are fundamental for anticipating food crisis and prioritizing interventions to avert acute food insecurity, acute malnutrition, famines, and mortality [30, 83]. EW-EA systems were primarily developed to prevent and address slow-onset climate risks, usually on seasonal scales, and have adaptation benefits [80]. Investments in EW-EA have shown to be cost-effective in reducing hunger and mortality induced by climate-related (and other) shocks. During the 2017 drought-induced food crisis in Kenya, half a million fewer people required humanitarian assistance than would be expected by similar droughts, due to effective EA triggered by EW [82]. As the frequency and magnitude of climate-related extreme events increase under climate change, and their potential impact on FSN intensifies, so does the need to anticipate when an extreme event might trigger a food crisis. EW has improved significantly, due to monitoring technologies, such as through Earth observation, and to new approaches of quantifying long-term, rather than only short-term risks, such as the integration of climate risk monitoring into FSN monitoring through the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC). The adoption of IPC indicator of acute food insecurity is critical to build resilience to the impacts of extreme climate events, by providing data on acute food insecurity and malnutrition which are used to determine severity of needs and the number of people in need of humanitarian assistance [21]. The IPC comprises a set of analytical tools and processes aimed at studying and classifying the severity of acute and chronic food insecurity, specifically designed to provide Governments, UN, and Humanitarian Assistance organizations with information in both emergency and development contexts [33]. The integration of climate risk monitoring into FSN monitoring has been a critical adaptation option to build resilience to the impacts of El Nino in the Dry Corridor in 2014–2016 [33]. Investments are needed to forecast crises and to establish forecast-based finance initiatives that prioritize limited resources [79, 142].

Nutrition-Sensitive Risk Reduction, Risk Management, Risk Sharing and Insurance

With increasing evidence that extremes climate events affect malnutrition [143,144,145,146], and those impacts will only exacerbate vulnerabilities and risks [147], there is a need to support communities that are vulnerable to nutrition insecurity and disaster risks. Current efforts have focused on risk assessments [148], improving emergency and contingency planning efforts [149], and promoting livelihood resilience [150]. Such approaches assume that solutions required to manage risks associated with future climate change are politically and financially feasible. Resilience to increasing extreme events can be accomplished through risk sharing and transfer mechanisms such as insurance markets and index-based weather insurance [2]. Financial transfer mechanisms and microinsurance schemes targeting nutrition-insecure households hold potential [91], especially when combined with other risk reduction approaches such as water catchment. For example, the World Food Programme-Oxfam R4 Rural Resilience Initiative in Ethiopia incorporates improved resource management (risk reduction), insurance (risk transfer), microcredit (prudent risk-taking), and savings (risk reserves) [151]. Communities participating in this initiative seek to reduce key climate risks while also insuring their livelihoods against unavoidable impacts [151]. Some studies caution about additional risks which poor households may bear with these insurance programs, including increased debt loads [152,153,154].

Cross-Cutting Factors for Climate Adaptation for Food Security and Nutrition: the Enablers

Women’s and Girls’ Empowerment

Strengthening women’s agency in promoting sustainable and diverse diets, resilient livelihoods, and local food systems is key to empowering women in addressing climate change impacts on nutrition. Empowered women have increased the climate resilience capacity of their communities for food security and nutrition [92, 155]. Women’s empowerment has been associated, in different cultural contexts, with higher resilience and adaptation capabilities as well as lower malnutrition rates [37, 93, 156]. Studies using long-term series and multiple variables showed that women’s empowerment through education and equality policies is key drivers of past reductions of malnutrition in more than 115 countries [9, 157]. The economic, social, and institutional arrangements needed to facilitate women’s empowerment may include targeting men in integrated agriculture programs to change gender norms and improve nutrition [93]. Moreover, addressing the gendered politics of access to food not only contributes to better adaptation practices but also to improved dietary diversity [38]. And, as a co-benefit with the agroecological practices described above, women’s empowerment and agroecology are mutually supportive. Agroecology as a paradigm, a praxis, and a movement challenges the gendered dimensions of traditional agriculture, empowering women to generate and control income, thus improving self-esteem, decision-making power, and leadership [94].

Education

In order to achieve transformation with combined adaptation measures that contribute to reduce the risk of malnutrition, education emerges as an effective approach with multiple co-benefits. Promoting a better understanding of climate change impacts and information about adaptation options, combined with higher male and female educational levels, is strongly associated with higher adoption of adaptation measures in Africa and Asia [95, 97, 99]. The number of adaptation practices adopted is positively associated with education [96], and more practices are linked to higher food security levels and lower poverty. Moreover, there is evidence that having better access to climate information is often a key success factor in adopting climate adaptation diversification [98]. The acquired knowledge is not usually expressed in individual isolation but shared with peers in order to gain legitimization of the adaptation measures through social acceptance [158]. Actually, having a better knowledge of the consequences of climate change for one’s livelihoods and how to adapt and mitigate through daily practices is relevant not only for food security and nutrition but also for other adaptation practices, being thus a multiplier of co-benefits.

Rights-Based Approaches and Good Governance

A multi-sectoral approach, institutional and cross-sectoral collaboration, and policy coherence, when based on human rights, due diligence, and good governance, can foster preventive and long-term adaptive and/or transformational interventions to address the impacts of climate change to malnutrition [33, 34, 100, 101]. Actually, food system resilience and food security adaptations are framed with multiple dimensions, encompassing political, economic, psychological, historical, and natural elements [104], and better food and nutrition security in itself can also contribute to higher resilience [105]. When rights-based approaches to climate change adaptation are followed, livelihood impacts last longer and are deeply internalized [102, 103]. Any climate adaptation framework must thus prioritize equitable outcomes and entrench good governance and accountability. There is an increasing recognition that addressing climate change is a component of realizing the right to health, and thus it shall be supported by appropriate legal and institutional frameworks [159]. As climate change and variability increase in scale and urgency, it will be critical to ensure respect for human rights while designing and implementing adaptation options [160].

Humanitarian, Development, and Peace Nexus

Food and water insecurities are drivers of social unrest and conflict and, at the same time, conflict-forced displacement, livelihoods loss, food insecurity and hunger are causes of conflict. Therefore, addressing hunger is a foundation for stability and peace. Nexus approach refers to strengthening collaboration, reducing overall vulnerability and unmet needs, strengthen risk management, and address root causes of conflict [40]. The approach to the humanitarian, development, and peace nexus (HDP) aims to address conflict-driven fragility, climate resilience, and chronic food and nutrition security [22]. Another nexus, the triple nexus in socio-environmental analysis and policymaking was previously conceptualized as the linkages between water, energy, and food [161], later on, enlarged with adaptive capacities [162]. The HDP nexus approach, including peace building and social cohesion interventions, seems relevant in areas where major drivers interact, namely in protracted food crises [21, 40, 108,109,110], with health in armed conflict [106], or for religious actors in food insecure areas [111].

Assessment of Feasibility and Effectiveness of Climate Change Adaptation for Food Security and Nutrition

The effectiveness of the adaptation options in reducing climate impacts and risks to FSN and malnutrition is determined by factors such as the nature and extent of the shock or risk, complementary/synergistic adaptation options in place across systems and sectors, existing socio-economic and political context, and adaptation enablers for FSN. Based on the evidence assessed in this paper, there is robust evidence and high agreement on the effectiveness of adaptation strategies for FSN that integrate options such as improved access to (i) sustainable, affordable, and healthy diets from local climate-resilient, nutrition-sensitive agroecological food systems; (ii) universal health care (including child, maternal, and reproductive health), water and sanitation systems, and integration of WASH in nutrition programs; (iii) nutrition-sensitive adaptive social protection; and (iv) anticipatory actions, EW-EA systems or adoption of the IPC Acute Food Insecurity classification among others. There is medium evidence and agreement of the effectiveness of risk reduction instruments, such as weather-related insurance, and risk management in reducing climate-induced food insecurity and nutrition risks.

The feasibility assessments in this study considered six dimensions (economic, technical, institutional, socio-cultural, environmental, geophysical) which are part of the standardized methodology applied throughout the different chapters of the IPCC AR6 WGII. Based in the literature assessed in this paper, the adaptation categories with the highest feasibility across dimensions, include (i) climate-resilient and agroecological local food systems; (ii) access to sustainable, affordable, and healthy diets, and (iii) nutrition-sensitive social protection. The latter presents socio-cultural and institutional barriers for implementation. The implementation of adaptation categories with focus on improved anticipatory actions and EW-EA systems and access to health, nutrition and water and sanitation services scored moderately or highly feasible. Based on the evidence assessed in this paper, risk reduction instruments, risk transfer, risk sharing, weather-based insurance, and risk management present feasibility challenges related to economic and institutional barriers.

The assessment of the relevance of cross-sectoral enablers with focus on women’s and girls’ empowerment has emerged as very relevant enabler for nutrition-sensitive community-based adaptation and other development realms [39, 97]. Enhanced education, including formal education for all and specific climate change education, and extension services targeted to improve access to climate information have shown to be instrumental to reduce FSN and malnutrition and other risks. The realization of human rights (particularly the right to health, the right to food, and the right to water) and good governance is highly relevant to reduce the risks and build resilience to the climate impacts on FSN. Enablers such as Social Cohesion and Peace Building (within the framework of the Humanitarian Development and Peace Nexus), although there is high agreement of their relevance for nutrition-sensitive adaptation, require further evidence and improved design research to become pivotal.

The analysis of exemplary case studies of the implementation of coordinated and/or integrated multi-sectoral climate adaptation options—to anticipate, respond, cope, and adapt—to the impacts and risks to FSN and malnutrition is fundamental to inform future needs, approaches, and timeframes for implementation required to build climate resilience. Based on the evidence of coordinated multi-sectoral adaptation efforts reviewed in this paper, multi-phased approaches and integration of effective adaptation options across sectors, systems, and scales are necessary for a timely implementation to prevent/respond to impacts and reduce risks of climate-related extreme events on livelihoods, acute food insecurity, and malnutrition. (1) Urgent adaptation measures are related to the anticipation and response to climate related food emergencies, and the assistance to the people affected by acute food insecurity and acute malnutrition, and require urgent humanitarian assistance to survive. Urgent measures include direct nutrition interventions, training in therapeutic feeding, food assistance, cash transfers, labor-based safety nets, and school meals among other. (2) Short-term approaches include the establishment of climate services, anticipatory actions, and multi-risk EW-EA systems to safeguard assets and save lives, and adoption of IPC Acute Food Insecurity classification and forecast-based finance initiatives, as tools to prevent and build resilience to climate impacts to FSN. These adaptation options need to be supported with improved access to nutrition, social protection, and health care. (3) Medium-term to long-term approaches to address climate risks to FSN include investments in rural development that promotes nutrition-sensitive agro-ecological local food systems to improve access to healthy and affordable diets, enhancing risk reduction, risk transfer, insurance/micro-insurance, and risk management, and investing in nutrition-sensitive adaptive social protection, universal health access, water and sanitation systems, and healthy environments.

Conclusions

In this paper we have assessed for the first time the feasibility and effectiveness of multi-sectoral climate adaptation strategies and options for food security and malnutrition in all its forms, including the relevance of cross-cutting adaptation enablers for implementation. The review of the evidence and the results of the assessments inform the contents and confidence statements of the section on “multi-sectoral adaptation for malnutrition” of the IPCC AR6 WGII Chapter 7: Health Wellbeing and the Changing Structures of Communities.

Considering the nature of the feasibility dimensions included in this assessment (i.e., economic, technical, social, institutional, environmental, and geophysical), these results can inform policy and decision makers, International Finance Institutions (IFIs), implementing organizations and stakeholders across sectors and systems (e.g.. agriculture, food, water, health, social protection, EWS).

One of the limitations is that the results are based in the evidence reviewed (case studies or empirical research in specific countries or regions), and, therefore, the results cannot be always extrapolated, as they should inform only regions with similar climate, geographical and socio-economic, and political contexts. Indeed, the information from the effectiveness and feasibility of adaptation options in the local context is critical for the successful implementation. The contextual information and existing trade-offs are available in most of the studies used in this assessment, and this would allow a regional and economic breakdown to consider options and outcomes.

The solution space for climate adaptation for food security and malnutrition in affected regions requires a focus on effective and feasible multi-sectoral nutrition-sensitive climate adaptation across food, water, health, and social protection systems. Anticipatory actions, EW-EA that trigger early actions for FSN; risk reduction; and risk management schemes, including weather-related insurance and forecast-based financing, are critical to build climate resilience. Safety nets, EWS, insurance, and education have been prioritized as feasible adaptation measures [43], and EWS and micro-finance have been prioritized in low and middle-income countries [71]. The integration of climate risk monitoring into FSN monitoring through the adoption of the IPC classification is a critical adaptation option to assess the severity of acute and chronic food insecurity for emergency and development purposes, and to build climate resilience. Integrated agroecological food systems where food and water are considered as human rights, public goods, and commons [163] offer opportunities to value food differently and thus to increase dietary diversity at household level while building local climate resilience. This is particularly relevant when community-based adaptation planning considers issues related to gender equality and empowerment, social justice, the resilience of indigenous food systems and diets, human rights, and the local management of natural resources and biodiversity.

Long-term adaptive social protection programs and rights-based approaches that support food insecure households and individuals through cash transfers or public work programs (or employment generation schemes), land reforms, insurance, extension of credit, or other effective actions have shown to be effective both in reducing climate risks of food insecurity and malnutrition, and in improving household livelihoods. Long-term adaptation would require aspirational system transitions aiming for transformative sustainable and healthy food systems and diets, and supported by universal access to social protection, health care, education, and food through school meal programs. These comprehensive and integrated long-term solutions are getting increasing attention in the context of the COVID-19 era and the need to build pandemic-resilient food systems.

Climate adaptation measures for nutrition have been absent in the health or food security sections of the National Adaptation Plans’ (NAPs) in most of the LDCs and LICs, where various forms of malnutrition coexist, mirroring a trend that was detected a decade ago [15, 34, 164]. Only 27% of the LDCs with NAPs have identified nutrition as a priority for adaptation, and only 26% of the LICs identified nutrition as a priority in their first NCD submissions. Until very recently climate adaptation solutions for nutrition were missing even in the Community-Based Adaptation network. One of the main reasons contributing to this gap is that malnutrition aspects were not considered in vulnerability assessments, reinforcing the importance of considering malnutrition in all its forms in national and local vulnerability assessments.

The needs, effectiveness, and feasibility of climate adaptation options to prevent acute food insecurity and malnutrition in all its forms are among the least frequently studied. Climate adaptation policy studies are still limited, and have been focusing on needs and socio-political and institutional settings of few western countries [165], and on major structural adaptation needs in LIC and LDCs, where, despite being affected by the triple burden of malnutrition, adaptation for FSN has not been prioritized. This review aims to inform the IPCC AR6 WGII and has expanded the type of multi-sectoral adaptation options for food security and malnutrition in all its forms, and including for the first-time gender equity, peace-building, and human-rights based enablers.

Poorly defined institutional roles between ministries and institutional capacity limitations and siloed approaches to agriculture, food security, and nutrition have been hindering the integrated multi-sectoral climate change adaptation options for FSN that are presented here. Further and better articulation between climate adaptation measures, NDCs, and zero hunger objectives may result in higher resilience and better food security and nutrition at individual, household, community, and national levels. There will be no resilient development with malnourished children, nor food security with individuals and communities that are highly vulnerable to climate change and at risk of extreme climate events.

In this context, Climate Resilient Development Pathways that combine multisectoral adaptation measures to address food insecurity and malnutrition urgent needs, and build individual, household, and ecosystem resilience, with ambitious mitigation policies that minimize food systems’ impacts to climate change, and improve access to local, affordable, and healthy diets, are critical to achieve SDG1, SDG2, SDG3, and SDG13, and ensure Climate Resilient Food Systems for all beyond 2030.

References

Springmann M, Godfray HCJ, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. PNAS. 2016;113(15):4146–51.

Mbow C, Rosenzweig C, Barioni LG, Benton TG, Herrero M, Krishnapillai M, et al. Food security. Geneve: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; 2019.

Beach R, Sulser T, Crimmins A, Cenacchi N, Cole J, Fukagawa N, et al. Combining the effects of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on protein, iron, and zinc availability and projected climate change on global diets: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3(7):E307–17.

Hasegawa T, Sakurai G, Fujimori S, Takahashi K, Hijioka Y, Masui T. Extreme climate events increase risk of global food insecurity and adaptation needs. Nat Food. 2021;2:587–95.

Sulser TB, Beach RH, Wiebe KD, Dunston S, Fukagawa NK. Disability-adjusted life years due to chronic and hidden hunger under food system evolution with climate change and adaptation to 2050. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(2):550–63.

Springmann M, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S, Garnett T, Godfray HC, Gollin D, et al. Global and regional health effects of future food production under climate change: a modelling study. Lancet. 2016;387(10031):1937–46.

Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: <em>The Lancet</em> Commission report. Lancet. 2019;393(10173):791–846.

Willett W, Rockstrom J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019;393(10170):447–92.

FAO/IFPRI. Progress towards ending hunger and malnutrition: a cross-country cluster analysis. Agricultural and food systems at a cross roads. Rome: FAO and IRPRI; 2020. p. 80.

IHME. Findings from the global burden of disease study 2017. Seatle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2018.

Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark M, Poore J, Herforth A, Webb P, et al. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ-Br Med J. 2020;370.

GNR. Global Nutrition Report (2020): Action on equity to end malnutrition. Development initiatives. 2020.

UNICEF/WHO/WBG. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank Levels and trends in child malnutrition: key findings of the 2019 Edition Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization, Geneva; 2019.

Galasso E, Wagstaff A. The economic costs of stunting and how to reduce them. World Bank Group; 2017.

UNSCN. 6th report on the world nutrition situation: progress in nutrition. Switzerland; 2010.

Tirado MC. Sustainable diets for healthy people and a healthy planet. United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition. Discussion paper. Italy, Rome. 2017.

Smith K, Woodward A, Campbell-Lendrum D, Chadee D, Honda Y, Liu Q, et al. Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In: Field C, Barros V, Dokken D, Mach K, Mastrandrea M, Bilir T, et al., editors. Climate Change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability part A: global and sectoral aspects contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 709–54.

Nkunzimana T, Custodio E, Thomas AC, Tefera N, Perez Hoyos A, Kayitakire F. Global analysis of food and nutrition security situation in food crisis hotspots. Ispra and Rome, Italy; Report by the European Commision Joint Research Center in collaboration with the FAO and the WFP. 2016.

FSIN. Global Report on Food Crises 2017. Rome: Food Security Information Network; 2017.

FSIN. Global Report on Food Crises 2018. Rome: Food Security Information Network; 2018.

FSIN. Global Report on Food Crises 2019. Rome: Food Security Information Network; 2019.

FSIN-GNAFC. Global Report on Food Crises 2020. Rome: Food Security Information Network and Global Network Against Food Crises; 2020.

FSIN-WFP. Global report on food crises 2017. Joint analysis for better decisions Rome: Food Security Information Network; 2018.

Liem A, Natari R, Jimmy Hall B. Digital health applications in mental health care for immigrants and refugees: a rapid review. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27(1):3–16.

Bryant SL, Gray A. Demonstrating the positive impact of information support on patient care in primary care: a rapid literature review. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(2):118–25.

Tricco A, Antony J, Zarin W, Strifler L, Ghassemi M, Ivory J, et al. A scoping review of rapid review methods. BMC Med. 2015;13:224.

Sharpe EE, Karasouli E, Meyer C. Examining factors of engagement with digital interventions for weight management: rapid review. JMIR Res Protoc. 2017;6(10):e205. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.6059.

GNR. Global nutrition report: shining a light to spur action on nutrition. Bristol: Development Initiatives; 2018.

Watts N, Amann M, Ayeb-Karlsson S, Belesova K, Bouley T, Boykoff M, et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: from 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. Lancet. 2018;391(10120):581–630.

FSIN-GNAFC. Global report on food crises 2021: a joint analysis for better decisions. Rome: Food Security Information Network and Global Network Against Food Crises; 2021.

Partners IG. Technical Manual Version 3.0: evidence and standards for better food security and nutrition decisions. Rome: Integrated Food Security Phase Classification; 2019.

Shekar M, Kakietek J, D’Alimonte M, Rogers M, Eberwein J, Akuoku J, et al. Reaching the global target to reduce stunting: an investment framework. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(5):657–68.

FAO/IFAD/UNICEF/WFP/WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building climate resilience for food security and nutrition. Rome, Italy. 2018

Tirado MC, Crahay P, Mahy L, Zanev C, Neira M, Msangi S, et al. Climate change and nutrition: creating a climate for nutrition security. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(4):533–47.

Alderman H. Leveraging social protection programs for improved nutrition: summary of evidence prepared for the Global Forum on Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programs, 2015. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2016.

WHO, USAID, UNICEF. Improving nutrition outcomes with better water, sanitation and hygiene: practical solutions for policies and programmes. World Health Organization. 2015.

Ruel MT, Quisumbing AR, Balagamwala M. Nutrition-sensitive agriculture: what have we learned so far? Glob Food Sec. 2018;17:128–53.

Nyantakyi-Frimpong H. Agricultural diversification and dietary diversity: a feminist political ecology of the everyday experiences of landless and smallholder households in northern Ghana. Geoforum. 2017;86:63–75.

Bezner Kerr R, Chilanga E, Nyantakyi-Frimpong H, Luginaah I, Lupafya E. Integrated agriculture programs to address malnutrition in northern Malawi. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3840-0.

OECD. DAC recommendation on the humanitarian-development-peace nexus: OECD Legal Instruments; 2019

IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In: Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pörtner H-O, Roberts D, Skea J, Shukla PR, Pirani A, Moufouma-Okia W, Péan C, Pidcock R, Connors S, Matthews JBR, Chen Y, Zhou X, Gomis MI, Lonnoy E, Maycock, Tignor M, Waterfield T editors. Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018, pp. 32

de Coninck H, Revi A, Babiker M, Bertoldi P, Buckeridge M, Cartwright A, et al. Strengthening and implementing the global response. Global Warming of 15 °C an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 15 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); 2018.

Singh C, Ford J, Ley D, Bazaz A, Revi A. Assessing the feasibility of adaptation options: methodological advancements and directions for climate adaptation research and practice. Clim Change. 2020;162(2):255–77.

Krishnamurthy PK, Lewis K, Choularton RJ. A methodological framework for rapidly assessing the impacts of climate risk on national-level food security though a vulnerability index. Glob Environ Chang. 2014;25:121–32.

Nelson G, Bogard J, Lividini K, Arsenault J, Riley M, Sulser T, et al. Income growth and climate change effects on global nutrition security to mid-century. Nat Sustain. 2018;1:773–81.

Hasegawa T, Fujimori S, Shin Y, Takahashi K, Masui T, Tanaka A. Climate change impact and adaptation assessment on food consumption utilizing a new scenario framework. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48(1):438–45.

Hasegawa T, Fujimori S, Shin Y, Tanaka A, Takahashi K, Masui T. Consequence of climate mitigation on the risk of hunger. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49(12):7245–53.

Smith MR, Myers SS. Impact of anthropogenic CO2 emissions on global human nutrition. Nat Clim Chang. 2018;8(9):834–9.

Bezner Kerr R, Kangmennaang J, Dakishoni L, Nyantakyi-Frimpong H, Lupafya E, Shumba L, et al. Participatory agroecological research on climate change adaptation improves smallholder farmer household food security and dietary diversity in Malawi. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2019;279:109–21.

Boedecker J, Odhiambo Odour F, Lachat C, Van Damme P, Kennedy G, Termote C. Participatory farm diversification and nutrition education increase dietary diversity in Western Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(3):e12803. https://doi.org/10.1111/mcn.12803.

Calderón CI, Jerónimo C, Praun A, Reyna J, Santos Castillo ID, León R, et al. Agroecology-based farming provides grounds for more resilient livelihoods among smallholders in Western Guatemala. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2018;42(10):1128–69.

D’Annolfo R, Gemmill-Herren B, Graeub B, Garibaldi LA. A review of social and economic performance of agroecology. Int J Agric Sustain. 2017;15(6):632–44.

HLPE. Agroecological and other innovative approaches for sustainable agriculture and food systems that enhance food security and nutrition. Rome: FAO; 2019.

Makate C, Wang R, Makate M, Mango N. Crop diversification and livelihoods of smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe: adaptive management for environmental change. SpringerPlus. 2016;5(1):1135.

Rogé P, Friedman AR, Astier M, Altieri MA. Farmer strategies for dealing with climatic variability: a case study from the Mixteca Alta Region of Oaxaca, Mexico. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2014;38(7):786–811.

Heckelman A, Smukler S, Wittman H. Cultivating climate resilience: a participatory assessment of organic and conventional rice systems in the Philippines. Renew Agric Food Syst. 2018;33(3):225–37.

Philpott S, Lin B, Jha S, Brines S. A multi-scale assessment of hurricane impacts based on land-use and topographic features. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2008;128:12–20.

Green R, Milner J, Dangour AD et al. The potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the UK through healthy and realistic dietary change. Clim Change. 2015;129:253–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-015-1329-y.

Hidalgo D, Witten I, Nunn P, Burkhart S, Bogard J, Beazley H, et al. Sustaining healthy diets in times of change: linking climate hazards, food systems and nutrition security in rural communities of the Fiji Islands. Reg Environ Chang. 2020;20(3):1–13.

Kim BF, Santo RE, Scatterday AP, Fry JP, Synk CM, Cebron SR, et al. Country-specific dietary shifts to mitigate climate and water crises. Glob Environ Chang. 2020;62:101926.

Murendo C, Kairezi G, Mazvimavi K. Resilience capacities and household nutrition in the presence of shocks. Evidence from Malawi. World Dev Perspect. 2020;20:100241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wdp.2020.100241.

Song M, Fung TT, Hu FB, Willett WC, Longo VD, Chan AT, et al. Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality association of protein intake with mortality association of protein intake with mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1453–63.

Springmann M, Clark M, Mason-D’Croz D, Wiebe K, Bodirsky BL, Lassaletta L, et al. Options for keeping the food system within environmental limits. Nature. 2018;562(7728):519–25.

de Pee S, Hardinsyah R, Jalal F, Kim BF, Semba RD, Deptford A, Fanzo JC, Ramsing R, Nachman KE, McKenzie S, Bloem MW. Balancing a sustained pursuit of nutrition, health, affordability and climate goals: exploring the case of Indonesia. Amer J Clin Nutr. 2021;114(5):1686–1697. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab258.

Stylianou KS, Fulgoni VL, Jolliet O. Small targeted dietary changes can yield substantial gains for human health and the environment. Nat Food. 2021;2:616–27.

Hirvonen K, Bai Y, Headey D, Masters W. Affordability of the EAT-Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8(1):e59–66.

Drake L, Fernandes M, Aurino E, Kiamba J, Giyose B, Burbano C, et al. School feeding programs in middle childhood and adolescence. BTI - child and adolescent health and development. In: Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC, editors. Disease control priorities (Volume 8): Child and adolescent health and development, 3rd edn. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2017 p. 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-0423-6_ch12.

Hamm M, Frison E, Tirado von der Pahlen M. Human health, diets and nutrition: missing links in eco-agri-food systems. TEEB for agriculture & food: scientific and economic foundations. Geneva: UN Environment; 2018. p. 11.

Kim SS, Nguyen PH, Yohannes Y, Abebe Y, Tharaney M, Drummond E, et al. Behavior change interventions delivered through interpersonal communication, agricultural activities, community mobilization, and mass media increase complementary feeding practices and reduce child stunting in Ethiopia. J Nutr. 2019;149(8):1470–81.

Sanson AV, Van Hoorn J, Burke SE. Responding to the impacts of the climate crisis on children and youth. Child Dev Perspect. 2019;13(4):201–7.

Scheelbeek P, Dangour A, Jarmul S, Turner G, Sietsma A, Minx J, et al. The effects on public health of climate change adaptation responses: a systematic review of evidence from low-and middle-income countries. Environ Res Lett. 2021;16(7). https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ac092c.

Asfaw A, Simane B, Hassen A, Bantider A. Determinants of non-farm livelihood diversification: evidence from rainfed-dependent smallholder farmers in northcentral Ethiopia (Woleka sub-basin). Dev Stud Res. 2017;4(1):22–36.

Asfaw S, Davis B. The impact of cash transfer programs in building resilience: insight from African countries. In: Fs W, As T, editors. Boosting growth to end hunger by 2025: the role of social protection. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI); 2018.

Béné C, Cornelius A, Howland F. Bridging humanitarian responses and long-term development through transformative changes—some initial reflections from the World Bank’s Adaptive Social Protection Program in the Sahel. Sustainability. 2018;10:1697.

Del Ninno C, Coll-Black S, Fallavier P. Social Protection Programs for Africa’s drylands. Washington, DC: The World Bank; 2016.

Gilligan DO. Safety nets for agriculture and nutrition. In: Agriculture for improved nutrition: seizing the momentum. Wallingford: CABI; 2019. p. 104–112. http://www.cabi.org/cabebooks/ebook/20193035302.

Johnson C, Bansha Dulal H, Prowse M, Krishnamurthy K, Mitchell T. Social Protection and climate change: emerging issues for research, policy and practice. Dev Policy Rev. 2013;31(s2):o2–18.

Ulrichs M, Slater R, Costella C. Building resilience to climate risks through social protection: from individualised models to systemic transformation. Disasters. 2019;43(S3):S368–87.

Choularton RJ, Krishnamurthy PK. How accurate is food security early warning? Evaluation of FEWS NET accuracy in Ethiopia. Food Secur. 2019;11(2):333–44.

Cools J, Innocenti D, O’Brien S. Lessons from flood early warning systems. Environ Sci Policy. 2016;58:117–22.

Ewbank R, Perez C, Cornish H, Worku M, Woldetsadik S. Building resilience to El Niño-related drought: experiences in early warning and early action from Nicaragua and Ethiopia. Disasters. 2019;43(S3):S345–67.

Funk C, Davenport F, Eilerts G, Nourey N, Galu G. Contrasting Kenyan resilience to drought: 2011 and 2017. USAID Special Report; 2018.

Funk C, Shukla S, Thiaw W, Rowland J, Hoell A, McNally A, et al. Recognizing the famine early warning systems network: over 30 years of drought early warning science advances and partnerships promoting global food security. Bull Am Meterol Soc. 2019;100(6):27.

Rüth A, Fontaine L, de Perez EC, Kampfer K, Wyjad K, Destrooper M, Amuron I, Choularton R, Bürer M, Miller R. Forecast-based financing, early warning, and early action. In: The Routledge companion to media and humanitarian action. New York and London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2017. p. 135–149. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781134969173/chapters/10.4324/9781315538129-15.

Aryal J, Sapkota T, Khurana R, Khatri-Chhetri A, Rahut D, Jat M. Climate change and agriculture in South Asia: adaptation options in smallholder production systems. Environ Dev Sustain. 2019;22:5045–75.

Atela J, Gannon KE, Crick F. Climate change adaptation among female-led micro, small, and medium enterprises in Semiarid areas: a case study from Kenya. In: Handbook of climate change resilience. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 1–18. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-71025-9_97-1.

Crate S, Nuttall M. Insuring the rain as climate adaptation in an Ethiopian agricultural community. In: Crate SA, Nuttal M, editors. Anthropology and Climate Change: Routledge; 2016. p. 373–87.

Fisher E, Hellin J, Greatrex H, Jensen N. Index insurance and climate risk management: addressing social equity. Dev Policy Rev. 2019;37(5):581–602.

Greatrex H, Hansen J, Garvin S, Diro R, Le Guen M, Blakeley S, et al. Scaling up index insurance for smallholder farmers: recent evidence and insights. CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agirculture and Food Security; 2015.

Jensen N, Barrett C. Agricultural index insurance for development. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2017;39(2):199–219.

Wilkinson E, Weingärtner L, Choularton R, Bailey M, Todd M, Kniveton D, et al. Forecasting hazards, averting disasters: implementing forecast-based early action at scale. Overseas Development Institute (ODI); 2018.

Alston M. Gender mainstreaming and climate change. Womens Stud Int Forum. 2014;47:287–94.

Bezner Kerr R, Lupafya E, Shumba L, Dakishoni L, Msachi R, Chitaya A, et al. “Doing Jenda Deliberately” in a Participatory Agriculture and Nutrition project in Malawi. In: Njuku J, Kaler A, Parkins J, editors., et al., Transforming gender and food security in the Global South. London: Routledge; 2016. p. 241–59.

Caceres-Arteaga N, Maria K, Lane D. Agroecological practices as a climate change adaptation mechanism in four highland communities in Ecuador. J Lat Am Geogr. 2020;19(3):47–73.

Alam GMM, Alam K, Mushtaq S. Climate change perceptions and local adaptation strategies of hazard-prone rural households in Bangladesh. Clim Risk Manag. 2017;17:52–63.

Ali A, Erenstein O. Assessing farmer use of climate change adaptation practices and impacts on food security and poverty in Pakistan. Clim Risk Manag. 2017;16:183–94.

Fadina A, Barjolle D. Farmers’ adaptation strategies to climate change and their implications in the Zou department of South Benin. Environments. 2018;5(1):15. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3298/5/1/15.

Mulwa CK, Visser M. Farm diversification as an adaptation strategy to climatic shocks and implications for food security in northern Namibia. World Dev. 2020;129(C):S0305750X20300322.

Tambo JA. Adaptation and resilience to climate change and variability in north-east Ghana. Int J Disaster Risk Reduction. 2016;17:85–94.

Bailey I, Buck LE. Managing for resilience: a landscape framework for food and livelihood security and ecosystem services. Food Secur. 2016;8(3):477–90.

Bizikova L, Tyler S, Moench M, Keller M, Echeverria D. Climate resilience and food security in Central America: a practical framework. Clim Dev. 2016;8(5):397–412.

Duyck S, Lennon E, Obergassel W, Savaresi A. Human rights and the Paris Agreement’s implementation guidelines: opportunities to develop a rights-based approach. Carbon Clim Law Rev. 2018;12(3):191–202.

Ensor J, Forrester J, Matin N. Bringing rights into resilience: revealing complexities of climate risks and social conflict. Disasters. 2018;42(S2):S287–305.

Jacobi J, Mukhovi S, Llanque A, Augstburger H, Kaser F, Pozo C, et al. Operationalizing food system resilience: an indicator-based assessment in agroindustrial, smallholder farming, and agroecological contexts in Bolivia and Kenya. Land Use Policy. 2018;79:433–46.

Raheem D. Food and nutrition security as a measure of resilience in the Barents Region. Urban Sci. 2018;2(3):72.

Horne S, Boland S. Understanding medical civil-military relationships within the humanitarian-development-peace ‘triple nexus’: a typology to enable effective discourse. BMJ Mil Health. 2020;jramc-2019-001382. https://jramc.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/jramc-2019-001382.

Fanning E, Fullwood-Thomas J. The humanitarian-development-peace nexus: what does it mean for multi-mandated organizations? OXFAM Discussion papers. 2019. https://doi.org/10.21201/2019.4436. Available online: https://policy-practice.oxfam.org/resources/the-humanitarian-development-peace-nexus-what-does-it-mean-for-multi-mandated-o-620820/.

Howe P. The triple nexus: a potential approach to supporting the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals? World Dev. 2019;124:104629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104629.

Vivekananda J, Schilling J, Smith D. Climate resilience in fragile and conflict-affected societies: concepts and approaches. Dev Pract. 2014;24(4):487–501.

WFP. Triple nexus: WFP’s contributions to peace beyond the annual performance report 2018 series. Rome: World Food Programme; 2019. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000111108/download/.

Agensky J. Religion, governance, and the ‘Peace–Humanitarian–Development Nexus’ in South Sudan. In: de Coning C, Peter M, editors. United Nations Peace Operations in a Changing Global Order. Cham: Palgrave: Palgrave Macmillan; 2019. p. 277–95.

Carr ER, Thompson MC. Gender and climate change adaptation in agrarian settings: current thinking, new directions, and research frontiers. Geogr Compass. 2014;8(3):182–97.

Editorial. Gender in conservation and climate policy. Nat Clim Change. 2019;9(4):255.

Dainese M, Martin EA, Aizen MA, Albrecht M, Bartomeus I, Bommarco R, et al. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity-mediated benefits for crop production. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaax0121.

Isbell F, Adler P, Eisenhauer N, Fornara D, Kimmel K, Kremen C, et al. Benefits of increasing plant diversity in sustainable agroecosystems. J Ecol. 2017;105:871–9.

Kremen C, Merenlender A. Landscapes that work for biodiversity and people. Science. 2018;362:eaau6020.

Bezner Kerr R, Madsen S, Stuber M, Liebert J, Enloe S, Borghino N, et al. Can agroecology improve food security and nutrition? A review. Glob Food Secur. 2021;29:100540.

Snapp SS et al. Agroecology and climate change rapid evidence eview: Performance of agroecological approaches in low- and middleincome countries. Wageningen, The Netherlands: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), CGIAR; 2021. p. 63–63. Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/10568/113487.

Wezel A, Casagrande M, Celette F, Jean-François V, Ferrer A, Peigné J. Agroecological practices for sustainable agriculture. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2014;34:1–20.

Debray V, Wezel A, Derkimba A, Roesch K, Lieblein G, Francis C. Agroecological practices for climate change adaptation in semiarid and subhumid Africa. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2018:1–28.

Pandey R, Aretano R, Kumar Gupta A, Meena D, Kumar B, Alatalo J. Agroecology as a climate change adaptation strategy for smallholders of Tehri-Garhwal in the Indian Himalayan Region. Small-scale For. 2017;16:53–63.

Schipanski ME, MacDonald GK, Rosenzweig S, Chappell MJ, Bennett EM, Bezner Kerr R, et al. Realizing resilient food systems. Bioscience. 2016;66(7):600–10.

Méndez V, Bacon C, Cohen R, Gliessman S, Editors. Agroecology: a transdisciplinary, participatory and action-oriented approach. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2016;37(1):3–18.

Vivero-Pol JL. The idea of food as commons: multiple understandings for multiple dimensions of food. In: Vivero-Pol JL, Ferrando T, DeSchutter O, Mattei U, editors. Routledge: Handbook of Food As a Commons; 2019. p. 25–41.

Bezner Kerr R, Young SL, Young C, Santoso MV, Magalasi M, Entz M, et al. Farming for change: developing a participatory curriculum on agroecology, nutrition, climate change and social equity in Malawi and Tanzania. Agric Hum Values. 2019;36(3):549–66.

Rosset P, Val V. The ‘Campesino a Campesino’ agroecology movement in Cuba. In: Vivero-Pol JL, Ferrando T, De Schutter O, Mattei U, editors. Routledge Handbook of Food As a Commons; 2018. p. 251–65.

Olney D, Pedehombga A, Ruel M, Dillon A. A 2-year integrated agriculture and nutrition and health behavior change communication program targeted to women in Burkina Faso reduces anemia, wasting, and diarrhea in children 3–12.9 months of age at baseline: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Nutr. 2015;145(6):1317–24. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.203539.

Marquis GS, Colecraft EK, Kanlisi R, Aidam BA, Atuobi-Yeboah A, Pinto C, et al. An agriculture–nutrition intervention improved children’s diet and growth in a randomized trial in Ghana. Maternal Child Nutrit. 2018;14(S3):e12677.

Ragasa C, Aberman N-L, Alvarez MC. Does providing agricultural and nutrition information to both men and women improve household food security? Evid Malawi Glob Food Secur. 2019;20:45–59.

Raghunathan K, Kannan S, Quisumbing AR. Can women’s self - help groups improve access to information, decision - making, and agricultural practices? The Indian case. Agric Econ. 2019;50(5):567–80.

Semba R, de Pee S, Kim B, McKenzie S, Nachman K, Bloem M. Adoption of the ‘planetary health diet’ has different impacts on countries’ greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Food. 2020;1:481–4.

Hirvonen Y, Headey D, Masters W. Affordability of the EAT–Lancet reference diet: a global analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e59–66.

Glover D, Poole N. Principles of innovation to build nutrition-sensitive food systems in South Asia. Food Policy. 2019;82:63–73.

Springmann M, Mason-D’Croz D, Robinson S, Wiebe K, Godfray HCJ, Rayner M, et al. Mitigation potential and global health impacts from emissions pricing of food commodities. Nat Clim Chang. 2017;7:69.

Springmann M, Wiebe K, Mason-D’Croz D, Sulser TB, Rayner M, Scarborough P. Health and nutritional aspects of sustainable diet strategies and their association with environmental impacts: a global modelling analysis with country-level detail. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2(10):e451–61.

Gonzalez Fischer C, Garnett T. Plates, pyramids and planets developments in national healthy and sustainable dietary guidelines: a state of play assessment. . Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Food Climate Research Network; 2016.