Abstract

Evolutionary psychological theories posit that higher social status is conducive to men’s reproductive success. Extant research from historical records, small scale societies, as well as industrialized societies, support this hypothesis. However, the relationship between status difference between spouses and reproductive success has been investigated less. Moreover, even fewer studies have directly compared the effect of status and status difference between spouses on reproductive success in men and women. Using data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) conducted between 2010 and 2017 (N = 55,875; 28,931 women) and operationalizing social status as standardized income and educational level (compared with same-sex peers), we examined how social status and relative status between spouses impact men’s and women’s mating and reproductive success. We found that (1) men with higher social status were more likely to have long-term mating (being in a marriage and/or not going through marriage disruption) and reproductive success, mainly through having a lower risk of childlessness; (2) women with higher social status were less likely to have mating and reproductive success; and (3) relative status between spouses had an impact on the couple’s reproductive success so that couples, where the husband had higher status compared to the wife, had higher reproductive success. Thus, social status positively impacted men’s reproductive success, but relative status between spouses also affected mating and impacted childbearing decisions.

Significance statement

In terms of standardized educational level and income among peers, social status positively predicts men’s mating and reproductive success in contemporary China. However, while a higher social status increases the probability of having at least one child, it does not predict a greater number of children for men. A status difference between spouses, on the other hand, consistently predicts having children. Thus, the higher the husband’s status relative to his wife, the greater the likelihood of having the first, second, and third children. The current results suggest that when examining the effect of status on mating and reproduction, social status and status within a family should be considered. We also stress the importance of exploring the potential proximate mechanisms by which a status difference influences childbearing decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to females’ higher obligatory parental investment in gestation and lactation compared with males in the case of mammals, including humans (Bateman 1948), females tend to provide more parental care and devote less energy to mating. This tendency, in turn, affects the operational sex ratio (Clutton-Brock 2007), skewing it toward males. Therefore, females can exert their preferences in mate selection, choosing males with a higher social status and more resources thus able to provide more parental investment (Trivers 1972). In humans, it has been found that women are choosier compared to men (Buss 1989; Buss and Schmitt 1993, 2019) and that there is more significant variance in men’s reproductive success as a result of sexual selection (Wilder et al. 2004; Betzig 2012).

Social status influences mating and reproductive success

As higher social status is accompanied by more resources being available for rearing offspring and women thus would be expected to prefer higher social status men as their mates (Trivers 1972), men with higher social status should in theory have greater mating success and reproductive success (i.e., more offspring) than men with lower social status. Empirical evidence has consistently shown that, in pre-industrial societies, higher-social status men achieved greater reproductive success (Mealey 1985; Clark and Hamilton 2006; Hu 2020). However, in modern societies, the association between social status and reproductive success is less clear. Some studies have found a null (Freedman and Thornton 1982; Perusse 1993) or negative relationship (Vining 1986) between social status and a man’s number of offspring, while others have found a positive relationship (Hopcroft 2006, 2019, 2021; Fieder and Huber 2007). What is worth noting is that although there is no positive relationship between social status and the number of offspring, Perusse (1993) found evidence suggesting that higher social status men had greater potential fertility — that is, higher copulation frequency. Fieder and Huber (2007) found that income was positively associated with reproductive success for men, mainly because they could reduce the risk of childlessness; after excluding men who had no children, the positive association between social status and reproductive success for men became non-significant. Similar relationships between social status and bachelorhood, as well as childlessness, were found in contemporary Sweden (Kolk and Barclay 2021). Hu (2020) found that the positive relationship between men’s social status and the number of offspring in historical China became non-significant after controlling for the number of marriages.

Taken together, these results suggest that in the past, a high social status would have contributed to men’s reproductive success primarily because of mating success (i.e., a greater number of mates) rather than having more children per partner. This is also consistent with the fact that the maximum number of offspring a woman can have is limited. Note that this explanation does not contradict evolutionary thinking as no prediction of higher social status being associated with an increased desired number of children is made. Instead, it is more likely that the higher reproductive success of high-social status individuals is an indirect result of having more sexual partners (Forsberg and Tullberg 1995) and engaging in more copulations (Perusse 1993; Hopcroft 2006), which would naturally lead to more pregnancies and offspring in the evolutionary past, but not necessarily at present. Thus, in modern secular societies where contraceptives are widely used and (serial) monogamy is the norm, the social status-fertility link may be less strong for men. However, based on both theoretical predictions of women’s preference for higher social status men (Buss 1989) and previous research examining the social status-reproductive success association in men (Hopcroft 2006, 2021; Fieder and Huber 2007), we would still expect men with higher social status to have greater long-term mating success, leading to a decreased likelihood of having no children at all.

On the other hand, according to parental investment theory, reproductive success tends to vary less for women at different points on the social status dimension compared with men, as lower status women are being selected against less than lower status men. That being said, women with a higher social status are more likely to have fewer children than their lower- social status counterparts in modern societies (Fieder and Huber 2007; Huber et al. 2010). From an evolutionary perspective, the lower fertility of higher social status women may partly originate from the interaction between the tendency for hypergamy and the norm of serial monogamy in modern societies. That is, women tend to marry partners who have a relatively higher social status compared with themselves, which is associated with mating and reproductive success for women (Bereczkei and Csanaky 1996). This tendency, however, could also result in spinsterhood at the top and bachelorhood at the bottom of society (Van Den Berghe 1960) in modern societies with a norm of serial monogamy. Research has shown that women with higher education and career prospects may be less desirable in the marriage market, which may result in lower marriage and fertility rates (Hwang 2016; Bertrand et al. 2020). As more women enter and succeed in higher education and careers, obtaining higher social status, hypergamy is less and less achievable, especially for high social status women. Indeed, a recent population-based study revealed that educational hypergamy (i.e., the pattern in which husbands have a higher educational level than their wives) is ending, while hypogamy (by women) is increasing (Esteve et al. 2016). Research from China also indicates that the expansion of higher education enhances the tendency for educational homogamy among younger cohorts (Hu and Qian 2016). Therefore, higher social status women may have lower mating success leading to decreased reproductive success (for opposing evidence in recent Western cohorts, see Torr 2011; Budig and Lim 2016).

Though women’s fertility along the social status dimension can be influenced by evolutionary logic, other important factors have been proposed and studied. Firstly, pursuing higher education and participating in the labor market tends to delay the age of a woman’s first marriage (Ikamari 2005), thus postponing reproduction (Mills et al. 2011). Moreover, the anticipation and planning of marriage can also impact women’s education levels. Research shows that in specific settings (e.g., rural India), the perceived incompatibility between higher education and preferred age of marriage in women is more significant, which impacts the parents’ decision toward their daughter’s education (Maertens 2013). Secondly, the cost of rearing a child increases as social status rises. Borg (1989) found that after controlling for the estimated net cost of a child, calculated by the sum of a child’s cost and benefits and the mother’s opportunity cost, the negative relationship between income and fertility became positive. Thirdly, evidence suggests that childbirth negatively affects women’s employment and income (Hofferth and Curtin 2006; Takeuchi and Otani 2007; Ejrnæs and Kunze 2013), suggesting a bi-directional relationship. All of these point to the complexity of the mechanisms involved.

Taken together, we hypothesized higher social status to be associated with greater mating success (staying in a marriage) and reproductive success for men but less mating success and reproductive success for women. More specifically, we hypothesized that:

-

1.

Higher social status increases the likelihood of being married for men but decreases it for women (H1).

-

2.

Among those who were or have been in a marriage, higher social status decreases the likelihood of marriage disruption for men but increases it for women (H2).

-

3.

Higher social status increases reproductive success for men but decreases it for women (H3).

The association of social status difference between spouses and their mating and reproduction

Besides influencing men and reproductive success via mating success, the tendency for hypergamy can also influence the reproductive success among those who have entered a marriage. That is, the social status difference between partners may also impact reproductive success. Women who marry higher social status men and men who choose younger women as mates have significantly more surviving children than those who pursue alternative mating strategies (Bereczkei and Csanaky 1996). A recent study from China found that women’s relatively higher social status compared to their partners negatively predicted the intention of having a second child (Qian and Jin 2018). Indirect evidence from marital quality also suggests that the social status difference between partners is important. Women who have higher relative social status compared with their male partner were more likely to suffer from domestic violence (Kaukinen 2004; Kayaoğlu 2021) which, from an evolutionary point of view, can be conceptualized as a male mate retention tactic (Shackelford et al. 2005; Kaighobadi et al. 2009). Moreover, women who have a relatively higher social status compared with their partner were more likely to separate and divorce (Heckert et al. 1998; Liu and Vikat 2007), though in recent US cohorts, this relationship seems to no longer hold (Schwartz and Han 2014; Schwartz and Gonalons-Pons 2016). Therefore, we hypothesized that among first-time married couples, the higher the relative social status of the husband compared with the wife, the greater will be their reproductive success (H4). We restricted this hypothesis to first-time married couples because the current dataset neither recorded individuals’ fertility by marriage nor contained social status information about the respondents’ ex-partners. Therefore, using the relative social status of the current partners to predict fertility through multiple marriages is theoretically problematic.

Age at first marriage can serve as an indicator of mating success in humans. Using historical data, Telford (1992) showed that higher social status is associated with earlier marriage for sons in China. As there is a trade-off between spending time searching for high-value partners and securing an available mate to reproduce with, men who have a relatively higher social status than their future partner may enter into marriage earlier than those not in this advantageous position. We hypothesized that for women, however, the tendency for hypergamy predicts that higher social status women may face more difficulty finding satisfactory partners, increasing the marriage age (H5). Evolutionary psychology also predicts that compared with women, men tend to prefer younger mates who are more fecund (Kenrick and Keefe 1992). However, men's reproductive function is less influenced by ageing than women, and wealth tends to accumulate with age. Therefore, men may make trade-offs between their partners' social status and age, but not women. We hypothesized that men who marry women of relatively lower social status than themselves have younger wives than those men who marry up. In comparison, women who marry men of relatively lower social status than themselves do not have younger husbands than those who marry up (H6). Note that in both hypotheses 5 and 6, we only propose the negative relationships due to trade-offs and do not state that the social status difference causes changes in the age of marriage.

To recap, regarding the social status difference between spouses, we hypothesized the following:

-

1.

Among first-time married couples, the higher the relative social status of the husband compared with the wife, the greater will be their reproductive success (H4).

-

2.

Higher social status men enter marriage at an earlier age, compared with their lower status counterparts. Higher social status women enter marriage at an older age, compared with their lower status counterparts (H5).

-

3.

Men who married lower status women would have younger wives while this does not hold for women who married lower status men (H6).

The relationships hypothesized in H1-3 have been partially examined and supported in previous studies (Hopcroft 2006, 2021; Fieder and Huber 2007) using WEIRD (Henrich et al. 2010) data. Thus, the corresponding analyses in the current study will be conceptual replications using different statistical methods and data (see Methods section). However, examining how the relative social status between married couples affects their mating and marriage outcomes (H4-6) has been studied less directly and, therefore, represents a relatively novel contribution to the literature.

Social status and reproduction in China

In China, the fertility rate has been declining due to social and economic development and the state’s policy on birth control (Lavely and Freedman 1990; Cai 2010; Piotrowski and Tong 2016) dating from the 1970s (Wang 2012). Thus, a popular conception of fertility decline in China is that the family planning policy mainly drives it. However, research has suggested that social and economic development play a more critical role, like other countries that have experienced a demographic transition (Cai 2010). Furthermore, previous research on social status and fertility in China has more focused on women’s fertility and found that education was negatively associated with fertility and childbearing intentions (Zheng et al. 2016), consistent with findings from other countries (Fieder and Huber 2007; Huber et al. 2010). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that despite being influenced by a strict policy, Chinese data remains suitable for examining the social status-fertility link.

Moreover, it is difficult, if not impossible, to find a modern industrialized state where the natural fertility of humans may be studied without the influence of any societal structures. As mentioned above, other countries have influenced fertility patterns by social policies (Jalovaara et al. 2019), albeit in the opposite direction. Analyses based on these data have been published and considered as evidence either for or against evolutionary hypotheses. Therefore, results from China are not just acceptable but essential for developing an unbiased understanding of the hypothesized social status-fertility link. However, at this moment, less is known about how social status impacts men’s marriageability and fertility in China. Yu and Xie (2015) employed mini-census survey data to study the determinants of marriageability in China. They found that economic prospects had an impact on marriage entry for men. However, direct evidence on reproductive success is still needed. To what extent does the higher social status – high reproductive success link in men hold in China demands further investigation.

Methods

The CGSS data

The Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS, http://cgss.ruc.edu.cn/) is a cross-sectional, nationwide social survey administrated by the National Survey Research Center at Renmin University of China conducted annually since 2003. The cycle-2 sampling design (2010–2019) uses a multi-stage sampling method (140 primary selection units and 480 secondary selection units) to collect representative urban and rural household data from 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities. The response rates of the surveys in the current analysis ranged from 71.5 to 74.3%. Considering the complex and multi-faceted nature of the CGSS project, we believe that neither the interviewers nor the respondents were aware of the hypotheses in the current study, making it double-blind.

The data employed in our research came from the 2010–2017 CGSS (2014 and 2016 data were unavailable), containing 55,875 (N female = 28,931, M age = 46.23, SD age = 13.62) face-to-face interviews with respondents born since 1945 who were at least 18 years old when surveyed. The reasons behind restricting the cohorts from 1945 onward were twofold. The first is that China instituted its primary education system in 1952 (Wu and Peng 2015), so collapsing earlier cohorts with later ones when examining the effects of education may not be a good approach. Second, family planning began around 1970 in China and impacted the fertility of Chinese families. Combined with a cultural preference for male offspring, this has resulted in higher rates of abortions targeting female fetuses and a skewed sex ratio (Ding and Hesketh 2006). Restricting the sample to cohorts from 1945 makes it relatively homogenous in terms of the family planning policy, as the 1945 cohort entered adulthood around the starting point of this policy. Although, it is also worth noting that, within this period of family planning, the policies of different stages may impact the social status-fertility link differently with the one-child policy in the 1990s, having the potential to attenuate the relationship to a greater extent.

Variables

Social status indicators in the CGSS

The annual total income (in CNY) of the interviewees, their partners, and their annual household income was the self-reported sum of income from all sources during the previous year, with an upper limit of ‘over 1,000,000 CNY’. Further, the educational levels of the interviewees and their partners have been measured continuously from 1 = “no education at all” to 13 = “graduate degree and above.”

Social status variables in the current analyses

Standardized income level

In the current analyses, the annual incomes of respondents were first log-transformed, then standardized according to the respondent’s region, sex, and year of the survey.

Standardized educational level

We standardized the continuous measurement of educational level based on five-year cohorts, sex, and respondents’ regions.

Absolute educational attainment

We recoded total education level into four categories: below high school, high school and equivalent, college or bachelor’s degree, and graduate degree and above.

Household income

Household income was first log-transformed, then mean-centered based on regions and the year of the survey.

Educational difference between spouses

We calculated educational differences in two steps: (1) subtracting the raw measure of the educational level of the respondent’s spouse from their own educational level, and (2) arranging the educational differences into deciles. Therefore, in the analyses, an educational difference of 1 indicates the respondent has an extremely low social status compared with their spouse, while an educational difference of 5 or 6 would show educational homogamy. The reason for arranging educational differences into deciles is that extreme values of raw differences can affect the regression results. Raw educational differences ranged from –12 to 11 (only one observation each at the two ends), with a standard deviation of 2.10 and a mean of 0.03.

Income differences between spouses

We calculated income differences by subtracting the log-transformed annual income of the respondent’s spouse from their own log-transformed annual income.

Because of the rapid expansion of education in China (e.g., in this dataset, 16.4% of the 1945–1950 cohort have a high school/vocational school diploma, while 70.9% obtained a diploma in the 1990–1995 cohort) and regional inequality in economic development (Yang 2002), the current analyses scaled income and education to locate respondents’ social status more accurately. This was done by accounting for the differences in living costs, the dissemination of education among different cohorts and regions, and income inequality between the sexes. We acknowledge that these standardization operations resulted in examining only the effect of social status (i.e., relative position compared with others), neglecting the effect of the absolute level of financial resources. We simultaneously put absolute (i.e., diplomas obtained) and standardized education levels (i.e., education level compared with same-sex peers in the same region) into models. We hoped to differentiate the multiple mechanisms by which education impacts mating and reproduction. Standardized education level and absolute educational attainment were only moderately correlated, r (55,775) = 0.29, p < 0.001, suggesting a level of collinearity that would not severely affect the regression results.

Mating and reproductive success

Marital status

Marital status was measured using a multiple-choice question including seven categories: unmarried, cohabitation, married, remarried, divorced, separated, and widowed in the CGSS2011-2017. In the CGSS 2010, no distinction was made between married and remarried. Unmarried refers to the status of being single and never having been married. In our analysis, we recoded those who reported being married but whose year of current marriage and year of the first marriage were not the same as remarried. All six categories except married (for the first time) were dummy-coded.

Number of children

The number of children was measured by asking participants for their total number of sons and daughters, including stepchildren, adopted children, and deceased children. CGSS2017 also asked participants for the total number of biological sons and daughters, including deceased biological children, but the size of this subsample is too small for reliable estimates. Therefore, to maintain the consistency of our analyses, we only reported the results for the number of children. Thus, we calculated the number of children as the sum of sons and daughters. To make sure that the total number of children is a valid measure of reproductive success, we ran Kendall’s rank correlation for the total number of children and the total number of biological children. The results show that the total number of children has a near-perfect correlation (τ = 0.983. z = 122.35, p < 0.001) with the total number of biological children, providing support for its validity.

Age of marriage

The age of marriage for the interviewee and their partners was calculated by subtracting their birth year from the year of their marriage. As the current dataset did not record the complete history of the interviewees, we restricted the analyses to first-time married couples only to avoid any confounding from multiple marriages.

Statistical analyses

Data preparation.

Before the statistical analyses, we reviewed the age of first marriage and number of offspring to identify and remove extreme values (e.g., age of marriage below 10, 59 cases; the number of son or daughters greater than 20, 4 cases) that were likely to be a result of data entry mistakes or misreporting.

Modelling.

We conducted all statistical analyses using R (version 4.1.0: R Development Core Team 2017). We used lme4 (Bates et al. 2015) to perform a series of (generalized) linear mixed-effects analyses using individual weights provided in the CGSS data. First, we examined the effect of marital status on the number of children (modelling results can be accessed in supplementary materials). Then, we examined the impact of social status as operationalized by standardized income, education level on mating success (H1: getting married, and H2: going through marriage disruption), and reproductive success (H3) while controlling for absolute educational attainment. Because of the sample size limitation, it was unrealistic to analyze data in separate cohorts. An offset variable is often used to control the differences of exposure length in Poisson or logit regressions (Hutchinson and Holtman 2005). Therefore, when examining the number of children, we used Poisson regression with age as an offset variable; that is, we entered logged age in the regression with a fixed coefficient of 1. As a result, the variables were predicting the rates in these models instead of counts (Gagnon et al. 2008). We used logit regression with age as an offset variable for the models with binary outcomes (e.g., childless, unmarried, and marriage disruption). In addition to social status, we also examined how relative social status between partners in terms of standardized income and education affects a couple’s reproductive outcome (H4: the number of children) and how relative social status between partners is associated with age at first marriage (H5: age at first marriage of the participant and H6: age at first marriage of their spouse) using (generalized) linear mixed models. While examining how status differences between couples may affect reproductive success, we controlled for household resources (i.e., annual household income centered by regions and year) and the average education level of the couple. In all models, we used random intercepts for regions and cohorts.

Results

In the combined sample, men on average had 1.43 children (SD = 1.04) and women had 1.57 children (SD = 1.06). Eighty-three percent (n = 22,354) of the men had at least one child, 50.4% (n = 11,213) had at least two children, and 31% (n = 3475) had at least three children. Eighty-eight percent of (n = 25,556) the women had at least one child, 52.7% (n = 13,397) had at least two children, and 32.9% (n = 4414) had at least three children. Before examining the associations between social status and mating, as well as reproductive success, we first examined the associations between marital status and reproductive success. Compared with those who were married for the first time, being unmarried (men: B = − 3.03, p < 0.001; women: B = − 3.22, p < 0.001), cohabiting (men: B = − 0.30, p < 0.001; women: B = − 0.17, p = 0.003) or divorced (men: B = − 0.39, p < 0.001; women: B = − 0.27, p < 0.001) were associated with fewer children in both men and women. Being remarried was associated with more children in both men (B = 0.13, p < 0.001) and women (B = 0.15, p < 0.001) (see supplementary materials for detailed regression results).

Effect of social status on long-term mating success and reproductive success

Both absolute educational attainment and standardized educational level, as well as income, were significant predictors of being unmarried for men and women (see Table 1). Specifically, sex interacted with standardized educational level and personal income to predict being unmarried. A higher standardized educational level and personal income decreased the probability of being unmarried for men. Meanwhile, a higher standardized income was associated with a greater likelihood of being unmarried for women, while standardized education level had no significant effect (supporting H1). Absolute educational attainment predicted being unmarried similarly for men and women, with higher educational attainment increasing the likelihood of being unmarried. Excluding those who were unmarried and cohabiting (i.e., those who had never been married), we conducted a second analysis to examine the predictive power of standardized income and education on the likelihood of going through marriage disruption (i.e., divorce or separation, Heckert et al. 1998). Results from Table 2’s right-half columns show that men with a higher standardized education and higher standardized income were less likely to experience marriage disruption. However, higher standardized education and income for women were both associated with a higher likelihood of marriage disruption (supporting H2). As for absolute educational attainment, compared with those who had high school level education, men and women who had a college education and above were less likely to go through marriage disruption. For men, those with less than a high school education were also less likely to go through separation or divorce. Robustness checks were run with different independent variables in the models (i.e., sex and standardized income; sex, standardized educational level, and absolute education attainment; sex, the summed score of standardized income and educational level, and absolute education attainment). The results were similar to the ones presented in Table 1 (see Table S2 in supplementary materials).

For reproductive success, we first examined how standardized personal income and education were associated with men’s and women’s total number of children while controlling for absolute educational attainment. Results showed that standardized personal income and education level were significant positive predictors of the number of children for men and significant negative predictors for women (see Table 2). Conversely, absolute educational attainment negatively predicted the number of children for both men and women. Robustness checks were also run with different independent variables and the results were similar to the ones presented in Table 2 (see Table S3 in supplementary materials).

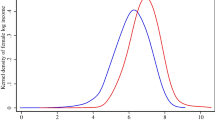

Even though the number of children is count data, one of the assumptions of Poisson regression is that each child’s birth is independent, which is not likely to hold up. Therefore, for more accurate analyses, we also ran logit models to examine how standardized personal income, education level, and absolute educational attainment predicted the following: having at least one child, having at least a second child among those who had children, and having at least three children among those who had two or more children. Results are presented in Table 3. For men, a higher standardized income increased the probability of having the first child but had no significant association with having a second child and decreased the likelihood of having a third child. Moreover, a higher standardized education increased the probability of having the first child, reduced the likelihood of having a second child, and did not predict having a third child. For women, a higher social status in terms of standardized education and income decreased the probability of having the first, second, and third children (supporting H3). The upper panels of Fig. 1 present the proportion of having at least one child along with income and standardized education deciles. As for absolute educational attainment, higher education levels were associated with a decreased likelihood of having children for both men and women. However, women with a graduate degree were more likely to have a second child than their high school-educated counterparts.

Mating and reproduction along social status and relative 1 status between couples. Age at first marriage was plotted using all cases while the mating as well as the reproductive outcome was plotted using only cases with age ≥ 40. The upper panels indicate that higher status men are less likely to be unmarried, going through marriage disruption or childless while the patterns are the opposite for women. For the lower three panels, decile 1 would indicate the respondent had an extremely lower status compared with their partner while decile 10 extremely higher status compared with their partner. Deciles 5–6 would indicate homogamy in terms of education level. Men who are relatively higher status compared with their spouse married at a younger age and had younger wives. The patterns are the opposite for women. Both hypergamy and homogamy are effective reproductive strategies

Effects of status differences on mating and reproductive success

We examined how relative social status between spouses was associated with reproductive success among first-time married couples. Table 4 presents how a spouse’s income and education relative to their partner’s predicted the likelihood of having children. In all models, we controlled for the average absolute education level (continuous measure) of the couple and household income. For men, higher relative social status than the spouse in terms of education and income was associated with a greater likelihood of having the first and second child. Higher education relative to the spouse, but not income, also increased the probability of having a third child. For women, the pattern was the opposite; higher relative social status in terms of education and income was associated with a decreased likelihood of having the first and second child. A higher education level relative to the partner, but not income, was also associated with a reduced chance of having a third child (supporting H4). Robustness checks without controlling for household income and average education level were run and the results were similar to the results presented in Table 4 (see Table S5 in supplementary materials).

Based on the assumption that, in general, men marrying early in life represents mating success and the trade-off between relative social status and a potential partner’s availability for marriage, we predicted that those with a relatively higher social status than their partner would marry at a younger age. The model results support this hypothesis (see Table 5, Fig. 1). A higher relative social status than one’s spouse, proxied by education and income differences, was associated with a lower age at first marriage in men. Conversely, in women, income and education had the opposite effect in predicting the age of first marriage, with higher relative status predicting an older age for a first marriage (supporting H5). A higher income and education level relative to their spouse predicted that men married a younger wife after controlling for their own age (supporting H6). For women, a higher education level relative to the spouse also negatively predicted the spouse’s age (going against H6). However, the effect was significantly smaller (see Table S4 supplementary materials for the interaction effect of sex and education difference on partner’s age).

Discussion

We utilized the 2010–2017 CGSS data to examine how social status is associated with Chinese men and women’s mating and reproductive success. In our analyses, due to the rapid expansion of education over the last few decades in China, we used statistical operations to separate the effect of standardized educational level (among same-sex peers) and absolute educational attainment. The results suggest that social status measured by standardized education level and income still predict reproductive success in terms of marital status and whether there are offspring in contemporary China. Furthermore, relative social status between spouses predicted the likelihood of having children and age at marriage among first-time married couples.

Effects of social status on mating and reproductive success

After isolating the effect of absolute educational attainment, men with a higher social status than their peers in terms of standardized education and income were more likely to be in a long-term relationship and stay in it. This result is consistent with the evolutionary hypothesis that higher social status is conducive to men’s mating success. In contrast, for women, social status had the opposite effect. However, the results do not warrant the conclusion that higher social status women have lower long-term mate value in the eyes of men. Although educated women have been perceived as less desirable, especially in cultures holding traditional gender roles (Hwang 2016; Bertrand et al. 2020), this decreased desirability may reflect the status concerns of men rather than the low mate value of high- social status women.

Furthermore, past research has suggested that women exhibit greater hypergamy than men (Van Den Berghe 1960). Therefore, women with higher income may tend to choose from men who earn more than they do, and as a result, they face a much smaller mating pool, increasing the difficulty of finding a suitable long-term mate. On the other hand, men may also prefer women who have equal or lower social status compared with themselves, which has been a successful reproductive strategy in the past (Bereczkei and Csanaky 1996). The penalty educated women face in the mating market (Hwang 2016; Bertrand et al. 2020) may result from social status concerns men may have (i.e., men may prefer to have partners who have relatively lower social status).

As for reproductive success, a higher standardized income and education level were associated with more children for men. However, closer examination revealed that standardized education and income were only significant in predicting the first child for men. For women, a higher social status was associated with a decreased likelihood of having children. Combined with previous studies showing that the social status-fertility relationship is primarily driven by the high risk of childlessness among lower social status men (Kolk and Barclay 2021), the current results suggest that social status, in terms of income and standardized education level, positively contributes to men’s but not women’s reproduction. This is done through mating success and a better chance at transitioning to parenthood instead of having more offspring in an industrialized societal setting. Moreover, the current results are consistent with previous studies in Western populations (Hopcroft 2006, 2021; Fieder and Huber 2007), suggesting that Chinese data are an appropriate and integral part of evolutionary demographic research. However, it is also important to note that fertility is a complex issue that is not only influenced by an individual’s social status but also societal changes (Newson et al. 2007), culture (McQuillan 2004), social welfare (Mills et al. 2011), and family planning policies (Liu and Liu 2020). Specifically, the way in which social status is associated with fertility change depending on regional or national social policies. For example, in more recent cohorts in Nordic countries, the negative relationship between women’s educational level and fertility is diminishing due to social welfare reforms (Jalovaara et al. 2019).

Relative status between spouses for predicting mating and reproductive success

Men who married relatively lower-social status women entered their marriages earlier and married a younger wife compared with those who married relatively high-social status women. This result is consistent with our hypothesis that men may make a trade-off between their partners’ social status (relative to themselves) and availability, as well as fecundity. However, as women do not necessarily prefer younger men as mates, we did not hypothesize a relationship between women’s status relative to their partner and their partner’s age. From Fig. 1, it is clear that women with a higher social status than their spouses married later and had older spouses. However, after controlling for their own age, we did find a weaker but significant negative effect of educational difference on the partner’s age for women. Therefore, though women with relatively higher social status compared with their spouses had older spouses, this pattern is mainly driven by the fact that higher social status women enter marriage at an older age.

For reproductive success, men who had higher relative social status than their spouses were more likely to have children. On the other hand, women were less likely to have children if their relative social status was higher. Notably, this pattern was significant after controlling for the couple’s household income and average educational level, suggesting that relative social status in terms of resource potential may impact women’s childbearing decisions. In Fig. 1, it is easy to see that besides hypergamy, homogamy is also associated with higher reproductive success. This is consistent with previous research, suggesting that both hypergamy and homogamy are successful strategies (Bereczkei and Csanaky 1996). The current results indicate that the relative social status difference between partners is more useful in predicting reproductive success.

One may be concerned that the observed relationship could be explained solely by women, not men, being more likely to stop their education after having their first child and, thus, having a lower education level than their husbands. Another mechanism for this phenomenon, that does not require an evolutionary strategic explanation, would be personality differences. That is, women with stronger career motivations may devote more energy to advancing their social status and are, thus, less likely to have children. Both hypotheses would receive additional support if the observed phenomenon were present only in cases with a higher educational background. However, using only cases where education was no higher than high school or its equivalent (i.e., a subset where childbirth conflicts less with pursuing an education and a career), we replicated the findings that if the male partner has a relatively higher social status, the couple will have higher fertility (see Table S6 in supplementary materials). As for evolutionary explanations, whether the relationship is because women are more likely to bear children if their partner has a relatively higher social status or because women’s relative social status versus their partner’s is simply a more accurate way to measure social status within a subpopulation, demands further research. If the former is true, investigating whether this pattern is driven by a worse relationship associated with hypogamy (Kaukinen 2004) could also be a research topic of both theoretical and practical value. It could inform policymaking that may ameliorate the fertility decline, such as promoting a culture where social status is less determined by personal income and education and more associated with aspects of familial and social life.

Limitations and future directions

Though the CGSS data provided us with a large representative sample with several mating and reproductive success measures, it has several limitations. First, in measuring reproductive success, most of the surveys in CGSS did not differentiate between biological versus non-biological children, nor did the measurements exclude children who were deceased before reaching the age of reproduction. Second, the surveys were not linked with official records. Thus, the data could suffer from inaccurate self-reporting, especially for men’s reproductive success (Hopcroft 2021), which is also supported by the current analysis that, on average, women (M = 1.57, SD = 1.06) had significantly more children than men (M = 1.43, SD = 1.04), F (1, 55,653) = 256.6, p < 0.001. Third, income from the previous year is not an accurate measure of social status compared with wealth. This might explain the fact that standardized education was a slightly better predictor in our models. Finally, the analyses only provide correlational, but not causal, evidence due to its cross-sectional design. These limitations should be noted when making inferences.

As for the analyses, to make the current research more focused and concise, we controlled regional and ecological differences with random intercepts for rural and urban areas for each provincial region. However, it is well acknowledged that in China, rural–urban dualism (Zhang et al. 2022) and ecological features such as agricultural style (Talhelm and English 2020) impact behavioral patterns. Therefore, how these differences are reflected in reproductive decisions and outcomes should be conceptualized and examined.

Regarding the interpretations of the findings, especially for the sex differences found in our research, we should consider the cultural and demographical differences between China and other regions. For example, the sex ratio bias in China could also be a causal factor for the above results. Because the sex ratio is biased toward men, women would, in theory, have more bargaining power in the mating market, biasing both sexes toward high investment. The potential influence of the family planning policy should also be taken into consideration. The fact that social status only positively predicted the likelihood of having the first child for men could result from the former one-child policy in China rather than reflect an inherent feature of the social status-reproduction relationship.

Studying the relationship between social status and reproductive success is only part of the picture. Thus, researchers should also integrate findings from other areas of evolutionary science — for example, the study of personality and individual differences conferring social status (Durkee et al. 2020), and behavioral genetics that links traits and genes (for a recent review, see Harden 2021). Specifically, recent research examining how the education-reproduction link could influence human population genetics found that because of the negative relationship between education and reproduction, selection has favored genetic variants associated with low educational attainments (Beauchamp 2016; Kong et al. 2017). Future research could extend our understanding by investigating the relationships between social status-conferring traits (phenotypes), genetics, and educational and financial achievements together and contextualizing the observed patterns by incorporating cultural and ecological factors.

Conclusions

While social status is associated with mating and reproduction, the data from China are still limited. Our research explored how standardized income and education were associated with mating and reproductive success using the cycle-2 CGSS data. Our results showed that higher social status is associated with more mating and reproductive success for men. Conversely, higher social status predicts lower mating success and reproductive success for women.

Furthermore, relative social status between married couples was associated with mating and reproductive success. Men who had a relatively high social status than their spouses married earlier with younger wives and were likely to have more children. The pattern was the opposite for women. The results were consistent with the evolutionary hypothesis that higher social status contributes to mating success for men. However, more research is needed to establish causation and to disentangle the specific mechanisms.

Data availability

CGSS is part of the East Asia Social Survey project. The anonymized CGSS data can be accessed at the Chinese National Survey Data Archive (http://www.cnsda.org/index.php?r=users/create) or the East Asia Social Survey website (https://www.eassda.org/pages/access.php). The former site is in Chinese while the latter site is in English. R code for data preparation and analyses can be accessed at OSF (https://osf.io/dhgqc/).

References

Bateman AJ (1948) Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 2:349–368

Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S (2015) Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw 67:1–48

Beauchamp JP (2016) Genetic evidence for natural selection in humans in the contemporary United States. P Natl Acad Sci USA 113:7774–7779

Bereczkei T, Csanaky A (1996) Mate choice, marital success, and reproduction in a modern society. Ethol Sociobiol 17:17–35

Bertrand M, Cortes P, Olivetti C, Pan J (2020) Social norms, labour market opportunities, and the marriage gap between skilled and unskilled women. Rev Econ Stud 88(4):1936–1978

Betzig L (2012) Means, variances, and ranges in reproductive success: comparative evidence. Evol Hum Behav 33:309–317

Borg MOM (1989) The Income–Fertility Relationship: Effect of the Net Price of a Child. Demography 26(2):301–310

Budig MJ, Lim M (2016) Cohort differences and the marriage premium: emergence of gender-neutral household specialization effects. J Marriage Fam 78:1352–1370

Buss DM (1989) Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behav Brain Sci 12:1–14

Buss DM, Schmitt DP (1993) Sexual strategies theory: an evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychol Rev 100:204–232

Buss DM, Schmitt DP (2019) Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annu Rev Psychol 70:77–110

Cai Y (2010) China’s below-replacement fertility: government policy or socioeconomic development? Popul Dev Rev 36:419–440

Clark G, Hamilton G (2006) Survival of the richest: the Malthusian mechanism in pre-industrial England. J Econ Hist 66:707–736

Clutton-Brock T (2007) Sexual selection in males and females. Science 318:1882–1885

Ding QJ, Hesketh T (2006) Family size, fertility preferences, and sex ratio in China in the era of the one child family policy: results from national family planning and reproductive health survey. Brit Med J 333:371–373

Durkee PK, Lukaszewski AW, Buss DM (2020) Psychological foundations of human status allocation. P Natl Acad Sci USA 117:21235–21241

Ejrnæs M, Kunze A (2013) Work and wage dynamics around childbirth. Scand J Econ 115:856–877

Esteve A, Schwartz CR, van Bavel J, Permanyer I, Klesment M, Garcia J (2016) The end of hypergamy: global trends and implications. Popul Dev Rev 42:615–625

Fieder M, Huber S (2007) The effects of sex and childlessness on the association between status and reproductive output in modern society. Evol Hum Behav 28:92–398

Forsberg AJL, Tullberg BS (1995) The relationship between cumulative number of cohabiting partners and number of children for men and women in modern Sweden. Ethol Sociobiol 16:221–232

Freedman DS, Thornton A (1982) Income and fertility: the elusive relationship. Demography 19:65–78

Gagnon DR, Doron-Lamarca S, Bell M, O’Farrell TJ, Taft CT (2008) Poisson regression for modeling count and frequency outcomes in trauma research. J Trauma Stress 21:448–454

Harden KP (2021) Reports of my death were greatly exaggerated: behavior genetics in the postgenomic era. Annu Rev Psychol 72:37–60

Heckert DA, Nowak TC, Snyder KA (1998) The impact of husbands’ and wives’ relative earnings on marital disruption. J Marriage Fam 60:690–703

Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A (2010) The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci 33:61–83

Hofferth SL, Curtin SC (2006) Parental leave statutes and maternal return to work after childbirth in the United States. Work Occupation 33:73–105

Hopcroft RL (2019) Sex differences in the association of family and personal income and wealth with fertility in the United States. Hum Nat 30(4):477–495

Hopcroft RL (2006) Sex, status, and reproductive success in the contemporary United States. Evol Hum Behav 27:104–120

Hopcroft RL (2021) High income men have high value as long-term mates in the U.S.: personal income and the probability of marriage, divorce, and childbearing in the U.S. Evol Hum Behav 42:409–417

Hu S (2020) Survival of the Confucians: social status and fertility in China, 1400–1900. Economic History Working Papers (307). London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK

Yang DT (2002) What has caused regional inequality in China? China Econ Rev 13:331–334

Hu A, Qian Z (2016) Does higher education expansion promote educational homogamy? Evidence from married couples of the post-80s generation in Shanghai, China. Soc Sci Res 60:148–162

Huber S, Bookstein FL, Fieder M (2010) Socioeconomic status, education, and reproduction in modern women: an evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol 22:578–587

Hutchinson MK, Holtman MC (2005) Analysis of count data using poisson regression. Res Nurs Health 28:408–418

Hwang J (2016) Housewife, “gold miss,” and equal: the evolution of educated women’s role in Asia and the U.S. J Popul Econ 29(2):529–570

Ikamari LDE (2005) The effect of education on the timing of marriage in Kenya. Demogr Res 12:1–28

Jalovaara M, Neyer G, Andersson G, Dahlberg J, Dommermuth L, Fallesen P, Lappegård T (2019) education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. Eur J Popul 35:563–586

Kaighobadi F, Shackelford TK, Goetz AT (2009) From mate retention to murder: evolutionary psychological perspectives on men’s partner-directed violence. Rev Gen Psychol 13:327–334

Kaukinen C (2004) status compatibility, physical violence, and emotional abuse in intimate relationships. J Marriage Fam 66:452–471

Kayaoğlu A (2021) Do relative status of women and marriage characteristics matter for the intimate partner violence? J Fam Issues. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211030030

Kenrick DT, Keefe RC (1992) Age preferences in mates reflect sex differences in human reproductive strategies. Behav Brain Sci 15:75–91

Kolk M, Barclay K (2021) Do income and marriage mediate the relationship between cognitive ability and fertility? Data from Swedish taxation and conscriptions registers for men born 1951–1967. Intelligence 84:101514

Kong A, Frigge ML, Thorleifsson G et al (2017) Selection against variants in the genome associated with educational attainment. P Natl Acad Sci USA 114:E727–E732

Lavely W, Freedman R (1990) The origins of the Chinese fertility decline. Demography 27:357–367

Liu J, Liu T (2020) Two-child policy, gender income and fertility choice in China. Int Rev Econ Finance 69:1071–1081

Liu G, Vikat A (2007) Does divorce risk in Sweden depend on spouses’ relative income? A study of marriages from 1981 to 1998. Can Stud Popul 34:217–240

Maertens A (2013) Social norms and aspirations: age of marriage and education in rural india. World Dev 47:1–15

McQuillan K (2004) when does religion influence fertility? Popul Dev Rev 30:25–56

Mealey L (1985) The relationship between social status and biological success: a case study of the Mormon religious hierarchy. Ethol Sociobiol 6:249–257

Mills M, Rindfuss RR, McDonald P, te Velde E (2011) Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum Reprod Update 17:848–860

Newson L, Postmes T, Lea SEG, Webley P, Richerson PJ, McElreath R (2007) Influences on communication about reproduction: the cultural evolution of low fertility. Evol Hum Behav 28:199–210

Perusse D (1993) Cultural and reproductive success in industrial societies: testing the relationship at the proximate and ultimate levels. Behav Brain Sci 16:267–283

Piotrowski M, Tong Y (2016) Education and fertility decline in China during transitional times: a cohort approach. Soc Sci Res 55:94–110

Qian Y, Jin Y (2018) Women’s fertility autonomy in urban China: the role of couple dynamics under the universal two-child policy. Chin Sociol Rev 5:275–309

R Development Core Team (2017) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.R-project.org

Schwartz CR, Gonalons-Pons P (2016) Trends in relative earnings and marital dissolution: are wives who outearn their husbands still more likely to divorce? RSF Russell Sage Found. J Soc Sci 2:218–236

Schwartz CR, Han H (2014) The reversal of the gender gap in education and trends in marital dissolution. Am Sociol Rev 79:605–629

Shackelford TK, Goetz AT, Buss DM, Euler H, Hoier S (2005) When we hurt the ones we love: predicting violence against women from men’s mate retention. Pers Relationship 12:447–463

Takeuchi M, Otani Y (2007) Cost of motherhood effects of childbirth on women’s and couple’s earnings (in Japanese). Osaka School of International Public Policy, Osaka University

Talhelm T, English AS (2020) Historically rice-farming societies have tighter social norms in China and worldwide. P Natl Acad Sci USA 117:19816–19824

Telford TA (1992) Covariates of men’s age at first marriage: the historical demography of Chinese lineages. Pop Stud 46:19–35

Torr BM (2011) The changing relationship between education and marriage in the United States, 1940–2000. J Fam Hist 36:483–503

Trivers RL (1972) Parental investment and sexual selection. In: Campbell B (ed) Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971. Aldine, Chicago, pp 136–179

Van Den Berghe PL (1960) Hypergamy, hypergenation, and miscegenation. Hum Relat 13:83–91

Vining DR (1986) Social versus reproductive success: the central theoretical problem of human sociobiology. Behav Brain Sci 9:167–187

Wang C (2012) History of the Chinese Family Planning program: 1970–2010. Contraception 85:563–569

Wilder JA, Mobasher Z, Hammer MF (2004) Genetic evidence for unequal effective population sizes of human females and males. Mol Biol Evol 21:2047–2057

Wu J and Peng Z (2015) Basic education school system reform in New China: History, Experience and Prospect. Educ Teach Res 10:32–38. https://doi.org/10.13627/j.cnki.cdjy.2015.10.007

Yu J, Xie Y (2015) Changes in the determinants of marriage entry in post-reform urban China. Demography 52:1869–1892

Zhang Y, Sun Q, Liu Y (2022) Social capital mediates the effect of socioeconomic status on prosocial practices: evidence from the CGSS 2012 survey. J Community Appl Soc 32:198–211

Zheng Y, Yuan J, Xu T, Chen M, Liang H, Connor D, Gao Y, Sun W, Shankar N, Lu C, Jiang Y (2016) Socioeconomic status and fertility intentions among Chinese women with one child. Hum Fertil 19:43–47

Acknowledgements

We thank the reviewers for providing us with a wealth of constructive comments to improve this work.

Funding

The current research is supported by the China Scholarship Council (NO.202106140025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Communicated by M. Raymond

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Santtila, P. Social status predicts different mating and reproductive success for men and women in China: evidence from the 2010–2017 CGSS data. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 76, 101 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-022-03209-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-022-03209-2