Abstract

Action-oriented summits like the 2018 Global Climate Action Summit and 2019 UN Climate Action Summit, have become a major feature of global climate governance. Their emphasis on cooperative initiatives by a host of non-state and local actors creates high expectations, especially when, according to the IPCC, governments’ policies still set the world on course for a disastrous 2.7 °C warming. While earlier studies have cautioned against undue optimism, empirical evidence on summits and their ability to leverage transnational capacities has been scarce. Here using a dataset of 276 climate initiatives we show important differences in output performance, with no improvement among initiatives associated with more recent summits. A summit’s focus on certain themes and an emphasis on minimal requirements for institutional robustness, however, can positively influence the effectiveness of transnational engagement. These results make an empirical contribution towards understanding the increasingly transnational nature of climate governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Action-oriented summits aim to engage a multiplicity of actors, alongside similar efforts, such as Conferences of the Parties (COPs) under the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) and processes such as the Lima–Paris Action Agenda (LPAA) and the Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action (MPGCA). These efforts have stimulated the launch of many transnational initiatives: collaborative arrangements that include at least one non-state or subnational actor, operate in at least two countries and commit to voluntary adaptation and mitigation efforts. Examples illustrate the heterogeneity of such initiatives, including the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI), Sustainable Energy for All (SE4ALL) and the Resilient Cities Acceleration Initiative.

Since 2014, there has been an enormous mobilization of climate action as well as growing research interest in such processes both inside and beyond the UNFCCC regime1. The UNFCCC records over 27,000 climate actions by more than 187,000 actors; UNEP Copenhagen Climate Center’s (UNEP-CCC) ‘Climate Initiatives Platform’ (CIP; https://climateinitiativesplatform.org/) records 284 large-scale cooperative initiatives (UNEP-CCC, 2022), that in turn engage over 30,000 participants2,3. While it is difficult to say how much of observed growth is attributable to UN-led mobilization efforts, the seemingly large scale of transnational action translates to notable potential impacts, including a narrowing of the global emissions gap, even when accounting for overlaps with national actions4,5,6,7,8. Initiatives could, if fully implemented, nearly close the gap to 2 °C by 20307,8, as well as generate substantial adaptation benefits9,10. However, one cannot assume the full implementation of commitments10. Moreover, while large-n studies overwhelmingly look at mitigation, many initiatives do not aim directly at reducing emissions and may instead seek to build climate resilience and adaptative capacity11,12. Indeed, scholars have argued that indirect impacts such as learning and innovation may be more important13,14. Despite the growth of transnational initiatives and their estimated potential, there is also little evidence regarding (ex-post) effectiveness due to limited systematic tracking of initiatives15,16.

Despite this knowledge gap, scholars have called for international organizations and governments to engage non-state actors towards collective climate goals through summits and mobilization processes17,18,19,20,21. ‘Orchestration’ has particularly become an important governance strategy22,23,24. It assumes the growth and replication of efforts as public actors (orchestrators) such as governments and international organizations convince non-state actors and networks (intermediaries) to leverage efforts by their peers and network members (target actors)25. This ‘orchestrator → intermediary → target’ strategy has been suggested for harnessing non-state and subnational mitigation potential25,26,27,28,29 but also to leverage adaptation benefits22,27,30,31. The expectation is that orchestration helps public actors to achieve more among actors that cannot simply be commanded, contracted or delegated tasks. Orchestration operates on an assumption of mutual dependence between a multiplicity of actors and a strengthening of horizontal relationships32, which seem particularly fitting with current climate governance. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are expected to progressively deliver emissions reductions; however, non-state efforts could give room for them to accelerate implementation and to increase ambition33.

Summits are by no means using orchestration as their only governance strategy. Climate summits can be associated with many functions, including agenda setting, improving inclusiveness and galvanizing national policies and institutions34,35. However, recent summits usually feature public actors in the role of orchestrator. Understanding climate initiatives can be a starting point for understanding, for example, variation among orchestration processes.

This study’s aim is limited to understanding the growing numbers of climate initiatives (Fig. 1) associated with summits and mobilization processes using a dataset that tracks their output performance. It makes an empirical contribution to debates on the increasingly transnational and orchestrated nature of climate governance and develops an initial evidence base for understanding the effectiveness of transnational climate initiatives associated with particular summits and mobilization processes36,37.

Tackling the challenging question of effectiveness

As changes in environmental quality are difficult to attribute to regimes38, let alone specific summits, scholarship has remained relatively silent on the extent to which summits have contributed to problem solving. Rather, they have concentrated on whether summits can create ‘constitutional moments’ for strengthening institutions39 or greater institutional capacity. This has provided invaluable insight into the evolution of institutions40,41, the emergence and expansion of international law42,43,44 and the furthering of (national) legalization45,46,47. Scholars have also highlighted the impact of summits on actors other than states, for example, women’s rights organizations and businesses34,48,49,50,51,52. By stimulating transnational interactions, summits have strengthened the capacity and role of some non-governmental actors35,53,54,55,56,57. Yet, the question remains whether summits orchestrate effective transnational initiatives. Here we do not fully answer the question of impacts; however, we aim to better understand the effectiveness of climate initiatives associated with summits.

The question of ‘effectiveness’ is conceptually and empirically challenging58,59,60. Effectiveness can be understood in related yet distinct terms, including compliance, behavioural and environmental changes, each engaging very different assessment methods61. On the basis of a literature review, others16 suggest to align disparate research contributions and to assess climate action by conjoining different conceptual understandings of effectiveness (targets, inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts) in a logical framework. Our study particularly builds on understanding effectiveness on the basis of outputs or achieved, tangible and attributable production of climate initiatives62. This focus stands out from other large-n climate initiatives tracking efforts, which generally lack information on ex-post impacts19,63. Moreover, the focus on outputs fits in an Eastonian political systems view of effectiveness, which assumes a logical progression between outputs, outcomes and impacts, in which the preceding effect is necessary for the next type of effect64,65,66. Within this progression, outputs can be understood as a minimal but necessary measure of effectiveness which could lead to behavioural changes (outcome) and environmental and social changes (impact). Our focus on outputs also helps to overcome perennial questions of attribution and challenges of comparing initiatives that vary greatly in scope and design.

For this study, the Climate Cooperative Initiatives Database (C-CID)3 was developed: a dataset of 276 transnational climate initiatives, covering 2017–2020. Initiatives were identified from announcements at global climate summits between 2014 and 2019, as well as records from the UNFCCC’s Global Climate Action Platform and UNEP-CCC’s Climate Initiatives Platform. Except for Chan and Amling22, who explored the prevalence of adaptation initiatives across summits, earlier studies4,7,8,64 did not relate data on transnational initiatives to respective summits and mobilization processes to gain a comparative understanding. C-CID contains data on inter alia actors, organizational characteristics, target setting, geography of implementation and the mobilization processes and summits to which initiatives are related. C-CID’s main dependent variable is output performance. To determine output performance, we inductively categorized initiatives’ functions (such as training, campaigning or technical implementation) and subsequently assessed whether initiatives produced outputs that are consistent with their main functions (Supplementary Tables 2–4). For example, an initiative promoting energy-saving behaviour should produce campaign materials or advertising. Importantly, we assume direct functions (such as creating new infrastructure) and indirect functions (such as campaigning or lobbying) as equally relevant. To generate our indicator, the ‘Function–Output–Fit’ (FOF), we divide the number of functions for which relevant outputs have been produced by the total number of relevant functions, resulting in a score between 0 and 1 (Supplementary Table 5), where ‘0’ indicates that an initiative has not produced relevant outputs and ‘1’ indicates relevant outputs for every relevant function.

Data were collected from publicly available sources, including websites, publications, social media, and event broadcasts, as well as correspondence with initiatives (Data availability). The data have been reviewed and updated annually (since 2014) by different coders to capture any changes in functions and activities and to ensure inter-coder reliability. Using C-CID and the output performance methodology allows identification of clusters of initiatives and factors associated with higher or lower output performance, including which summits are associated with more or less effective initiatives.

Despite advantages, this method does have limitations. First, it does not indicate progression in absolute terms (for example, the scale of emissions reduction), neither does it guarantee problem solving. However, it can be combined with other assessment approaches to estimate problem solving, for instance vis-à-vis global mitigation efforts6,8. Such analysis, however, is beyond the scope of the current study. Second, initiatives set different levels of ambition and propagate and adopt different approaches. Despite this variation, we consider initiatives that share essential features (described above). Third, we cannot assume that initiatives are acting in good faith and without ulterior motives; non-state actors may promote selfish interests while giving a false impression of generating broad societal benefits. This study refrains from determining whether an initiative is genuine or ambitious. Rather, we focus on the relative performance at the level of orchestration processes, by comparing different transnational initiatives associated with different summits and processes and by analysing the differentials between them. Finally, this study does not allow dispositive causal claims to be made that trace causal mechanisms between an orchestrator’s actions and the performance of initiatives, neither do we aim to test orchestration theory. In fact, our study does not provide data on the actual orchestration processes, for example who orchestrators are, what priorities they set, how they legitimize their mobilization efforts and so on, nor does it assess the effectiveness of orchestration efforts per se, as orchestration involves many functions, among which transnational initiatives may only be one19,25,30.

Using the above method and a mix of descriptive inference along with multivariate regression, we address the following questions:

-

(1)

How does output performance vary across different summits and mobilization processes; is it improving over time?

-

(2)

What features of initiatives might explain differences in effectiveness?

-

(a)

Are different substantive foci (for example, on across thematic areas) associated with different levels of output performance?

-

(b)

Do summits or processes that emphasize institutional robustness yield initiatives with stronger organizational features and higher output performance?

-

(a)

Regarding the first question, scholars have highlighted learning and collaboration between orchestrators65,66,67,68 which could lead to better performance over time. For instance, the 2014 UN Climate Summit was convened by the UN Secretary General, which was quickly followed by the LPAA, featuring a collaboration effort between Peru and France—successive presidencies of the UNFCCC COP—as well as the Office of the UN Secretary General and the UNFCCC secretariat. Subsequently, in 2016 the MPGCA was established, again involving the French government and Morocco (then president of the UNFCCC COP) with support from the UNFCCC Secretariat and newly appointed ‘High-Level Climate Champions’69,70. Even summits beyond the UNFCCC context, including the ‘Climate Chance Summits’ (since 2016) and ‘One Planet Summits’ (2017, 2018 and 2019), the ‘Climate Action Partnership’ (CAPP 2017 and 2018), the 2018 Global Climate Action Summit (GCAS 2018) and the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit (UNCAS 2019) would frequently involve consultation and coordination with the UNFCCC process. These summits and process therefore not only share the basic governance logic of realizing climate goals through transnational engagement but also are linked through their collaborations with the UNFCCC and with orchestrators of preceding processes and summits.

Regarding the second question, effectiveness of initiatives may relate to their substantive foci. For instance, orchestrators may prioritize climate change mitigation or adaptation. Previous studies suggest a relative underperformance of adaptation initiatives, compared to mitigation initiatives11,22. Subsequently, summits and initiatives that focus more on mitigation initiatives may perform better than those that focusing on adaptation.

Finally, studies emphasize the importance of institutional robustness, such as the presence of monitoring frameworks, dedicated secretariats, assigned budgets and so on, for effectiveness47,71,72. Subsequently, orchestrators may set conditions regarding ‘procedures and reporting’ or the design of initiatives to ensure greater institutional robustness and better-performing initiatives.

Transnational initiatives across summits and processes

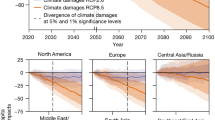

Considering output performance over time, we apply standard t-tests to compare initiatives under successive orchestration efforts (Supplementary Table 8) and find that average output is not increasing over time. In fact, the earlier 2014 UN Climate Summit (FOF_max 0.64***) and LPAA (FOF_max 0.66***) perform well above average, while One Planet Summits (since 2016, FOF_max 0.43*) and the Climate Action Pacific Partnership conferences (since 2017, FOF_max 0.29*) perform well below average (Fig. 2). The 2018 Global Climate Action Summit, a more recent orchestration effort, shows average performance (FOF_max 0.52).

The x axis is FOF_max, indicating initiatives’ output performance which makes desirable social and environmental change more likely. Values range from ‘0’ (no output, left) to ‘1’ (full fit between all functions and outputs, right). The y axis is the kernel density (or proportion) of initiatives. Kernel densities are closely related to histograms. Distributions for each summit along with means are indicated. Initiatives launched at recent summits (2017 and 2018) have a lower proportion of high scores (and a higher proportion of low scores) than those launched at earlier summits (2014 and 2015). Source: own data.

In line with previous investigations11,22, we find that adaptation initiatives significantly underperform (Supplementary Table 11). While earlier studies suggested that underperformance may be due to the late inclusion of adaptation initiatives in orchestration processes and their relative novelty11, we find underperformance even when age and a host of controls are included in multivariate regressions (Supplementary Table 12). Indeed, across almost all summits, adaptation initiatives underperform compared to mitigation initiatives (Supplementary Table 9). In the baseline model, adaptation initiatives had FOF_max scores about 10% lower than others, all else equal.

Different thematic emphases may also explain differences in performance. While mitigation-focused initiatives are not statistically distinguishable from the population, we see higher performance in thematic areas that typically emphasize mitigation approaches; in particular transport (FOF_max 0.60**), energy (FOF_max 0.55*) and industry (FOF_max 0.57*), show higher output performance (Supplementary Table 8).

Our findings generally confirm that the presence of monitoring arrangements and designated secretariats are particularly strong drivers of output performance. In the baseline model (Supplementary Table 12), having a secretariat or a monitoring arrangement is associated with a 15% increase in output performance. Applying t-tests comparing summits on institutional robustness indicators, we find that initiatives associated with the 2014 UN Climate Summit and the LPAA are much more likely to have secretariats, monitoring and budgets (Supplementary Table 10). The 2018 Global Climate Action Summit, One Planet Summits and the Climate Action Pacific Partnership Conferences perform (well) below average. We do not see significant effects of initiative openness to new partners (institutional openness) or budget transparency, although this may be due to limited data availability.

The importance of tracking transnational action

The emphasis on transnational climate action in global climate governance since 2014 has created high expectations. As the world remains on course for an estimated 2.7 °C warming by the end of the century73,74,75,76, transnational alternatives promise additional climate mitigation and adaptation efforts. Although empirical evidence on the performance of initiatives has been scarce, many suggestions have been made for orchestrating non-state capacities, for instance through summits18,77,78. Indeed, the number of summits and non-state mobilization efforts has rapidly increased17,79.

This study demonstrated significant variability in performance and outcomes of initiatives associated with different orchestration processes. We do not find evidence that initiatives and summits in the context of the UNFCCC have become more effective, despite learning and cooperation among orchestrators. While there is uncertainty as to why this is the case, a plausible explanation may be that successive orchestration efforts have led to diminishing returns. Initial initiatives may be more easily orchestrated around ‘low-hanging fruit’ but as orchestrators increasingly aim at more actions and harder-to-reach actors, it becomes increasingly difficult to generate effective action. Successive orchestration efforts might also target the same networks and actors leading to ‘summit fatigue’ among target actors.

The effectiveness of summits and orchestration processes between climate conferences may also depend on their thematic focus. We find a relative underperformance of adaptation initiatives. This may relate to the fact that such initiatives more frequently target developing countries, where infrastructure, institutional capacities and resources are often weaker. Moreover, initiatives perform better, if they reside in thematic areas more often associated with mitigation such as energy, transport and land-use. This may be explained by the pre-existence of strong sectoral networks that provide an opportunity structure for multiple actors to engage with international climate goals80 but also to align activities and to consistently liaise with orchestrators such as the UN climate secretariat. For instance, the transport sector is densely populated with such networks, including the the Partnership on Sustainable Low-Carbon Transport (SLoCaT) and the International Association of Public Transport (UITP). By contrast, ‘oceans and coastal zones’ see few transnational networks; with 12 partners from eight countries, the ‘Future Oceans Alliance’, is dwarfed by UITP’s more than 1,700 members. Performance should therefore be considered against the substantive issues that initiatives seek to address.

Finally, better-performing summits and mobilization processes are more frequently associated with transnational initiatives that have secretariats and monitoring arrangements. This suggests that orchestrators could positively influence performance by setting minimal requirements for institutional robustness among the initiatives they engage43.

As the trend towards orchestration and transnational climate initiatives is likely to continue, tracking their effects becomes increasingly important. This study demonstrates a political systems approach to tracking transnational climate initiatives. Our approach helps to overcome questions of attribution and the challenge of comparing a large, varied and growing number of initiatives. However, output performance can only be understood as a minimal indicator. Future investigations should combine approaches to, for example, more accurately estimate the scale of environmental and social impacts16. Moreover, qualitative investigations remain important, for example to understand whether orchestrators’ and initiatives’ goals are compatible or whether actors act with ulterior motives while giving the impression of supporting broad societal goals. Hence, the appraisal of performance should be part of a broader research agenda which combines quantitative and qualitative methods to explore different aspects of transnational engagement.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data that support the findings in this research are available from the corresponding author S.C. upon reasonable request.

References

Aykut, S. Taking a wider view of climate governance: moving beyond the ‘iceberg,’ the ‘elephant,’ and the ‘forest’. WIREs Clim. Change 7, 318–328 (2016).

UNFCCC/Marrakech Partnership. Yearbook of Global Climate Action 2018 (UNFCCC, 2018).

Chan, S., Deneault, A. & Hale, T. Climate—Cooperative Initiatives Database (C-CID) dataset (2021) (German Development Institute/ Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Blavatnik School of Government at the University of Oxford, 2020).

Roelfsema, M., Harmsen, M., Olivier, J. J. G., Hof, A. F. & van Vuuren, D. P. Integrated assessment of international climate mitigation commitments outside the UNFCCC. Glob. Environ. Change 48, 67–75 (2018).

Hsu, A. et al. in United Nations Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report 2018 Ch. 5 (UNEP, 2018).

Global Climate Action from Cities, Regions and Businesses (New Climate, 2019).

Kuramochi, T. et al. Beyond national climate action: the impact of region, city, and business commitments on global greenhouse gas emissions. Clim. Policy 20, 275–291 (2020).

Lui, S. et al. Correcting course: the emission reduction potential of international cooperative initiatives. Clim. Policy 21, 232–250 (2020).

Dovie, D. B. K. Case for equity between Paris Climate agreement’s co-benefits and adaptation. Sci. Total Environ. 656, 732–739 (2019).

Swart, R. & Raes, F. Making integration of adaptation and mitigation work: mainstreaming into sustainable development policies? Clim. Policy 7, 288–303 (2007).

Chan, S., Falkner, R., Goldberg, M. & Van Asselt, H. Effective and geographically balanced? An output-based assessment of non-state climate actions. Clim. Policy 18, 24–35 (2018).

Chan, S. et al. Promises and risks of non-state action in climate and sustainability governance. WIREs Clim. Change 10, e572 (2019).

Bernstein, S. & Hoffmann, M. The politics of decarbonization and the catalytic impact of subnational climate experiments. Policy Sci. 51, 189–211 (2018).

Hale, T. Transnational actors and transnational governance in global environmental politics. Ann. Rev. Pol. Sci. 23, 203–220 (2020).

Hsu, A. et al. A research roadmap for quantifying non-state and subnational climate mitigation action. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 11 (2019).

Hale, T. N. et al. Sub- and non-state climate action: a framework to assess progress, implementation and impact. Clim. Policy 21, 406–420 (2021).

Abbott, K. W., Genschel, P., Snidal, D. & Zangl, B. (eds) International Organizations as Orchestrators (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Hale, T. & Roger, C. Orchestration and transnational climate governance. Rev. Int. Organ. 9, 59–82 (2014).

Chan, S. & Pauw, W. P. A Global Framework for Climate Action (GFCA): Orchestrating Non-state and Subnational Initiatives for More Effective Global Climate Governance (German Development Institute/ Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), 2014).

Betsill, M. et al. Building productive links between the UNFCCC and the broader global climate governance landscape. Glob. Environ. Politics 15, 1–10 (2015).

Chan, S. et al. Reinvigorating international climate policy: a comprehensive framework for effective non-state action. Glob. Policy 6, 466–473 (2015).

Chan, S. & Amling, W. Does orchestration in the Global Climate Action Agenda effectively prioritize and mobilize transnational climate adaptation action? Int. Environ. Agreem.-P. 19, 429–446 (2019).

Bäckstrand, K. & Kuyper, J. W. The democratic legitimacy of orchestration: the UNFCCC, non-state actors, and transnational climate governance. Environ. Politics 26, 764–788 (2017).

Widerberg, O. The ‘Black Box’ problem of orchestration: how to evaluate the performance of the Lima–Paris Action Agenda. Environ. Politics 26, 715–737 (2017).

Abbott, K. W. & Snidal, D. Strengthening international regulation through transmittal new governance: overcoming the orchestration deficit. Vanderbilt J. Transnatl Law 42, 501 (2009).

Blok, K., Höhne, N., Van Der Leun, K. & Harrison, N. Bridging the greenhouse-gas emissions gap. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 471–474 (2012).

Emissions Gap Report 2020 (UNEP, 2020).

Hsu, A., Cheng, Y., Weinfurter, A., Xu, K. & Yick, C. Track climate pledges of cities and companies. Nature 532, 303–306 (2016).

Gordon, D. J. Global urban climate governance in three and a half parts: experimentation, coordination, integration (and contestation). WIREs Clim. Change 9, e546 (2018).

Graham, E. & Thompson, in International Organizations as Orchestrators (eds Abbott, K., Genschel, P., Snidal, D., & Zangl, B.) 114–138 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Adaptation Gap Report 2020 (UNEP, 2021).

Abbott, K. W., Genschel, P., Snidal, D. & Zangl, B. Two logics of indirect governance: delegation and orchestration. Br. J. Political Sci. 46, 719–729 (2016).

Dimitrov, R., Hovi, J., Sprinz, D. F., Saelen, H. & Underdal, A. Institutional and environmental effectiveness: will the Paris Agreement work? WIREs Clim. Change 10, e583 (2019).

Seyfang, G. Environmental mega-conferences—from Stockholm to Johannesburg and beyond. Glob. Environ. Change 13, 223–228 (2003).

Death, C. Summit theatre: exemplary governmentality and environmental diplomacy in Johannesburg and Copenhagen. Environ. Politics 20, 1–19 (2011).

Bakhtiari, F. International cooperative initiatives and the United Nations framework convention on climate change. Clim. Policy 18, 655–663 (2018).

Hsu, A., Brandt, J., Widerberg, O., Chan, S. & Weinfurter, A. Exploring links between national climate strategies and non-state and subnational climate action in nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Clim. Policy 20, 443–457 (2020).

Krasner, S. D. Structural causes and regime consequences: regimes as intervening variables. Int. Organ. 36, 185–205 (1982).

Biermann, F. et al. Navigating the Anthropocene: improving Earth system governance. Science 335, 1306–1307 (2012).

Sands, P. Greening International Law Vol. 1 (Earthscan, 1993).

Andresen, S. in Handbook of Global Environmental Politics (ed. Dauvergne, P.) 87–96 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012).

Paradell-Trius, L. Principles of international environmental law: an overview. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 9, 93–99 (2000).

Overall Progress Achieved Since the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, Report of the Secretary-General (United Nations Commission on Sustainable Development, 1997).

Haas, P. M. The road from Rio: why environmentalism needs to come down from the summit. Foreign Affairs www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2012-08-16/road-rio (2012).

Fahn, J. Rio+20 side events become the main event. Columbia Journalism Review www.cjr.org/the_observatory/rio20_coverage_outcome_environ.php (2012).

Chan, S. in Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Governance and Politics (eds Pattberg, P. & Zelli, F.) 275–280 (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2015).

Pattberg, P., Biermann, F., Chan, S. & Mert, A. (eds) Public–Private Partnerships for Sustainable Development: Emergence, Influence and Legitimacy (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2012).

Seyfang, G. & Jordan, A. in Yearbook of International Cooperation on Environment and Development (eds Stokke, O. S. & Thommessen, Ø.B.) 19–39 (Earthscan, 2002).

Conca, K. Environmental governance after Johannesburg: from stalled legalization to environmental human rights. J. Int. Law Int. Relat. 1, 121–138 (2005).

Friedman, E. J. The effects of ‘transnationalism reversed’ in Venezuela: assessing the impact of UN global conferences on the women’s movement. Int. Fem. J. Politics 1, 357–381 (1999).

Downie, C. Transnational actors in environmental politics: strategies and influence in long negotiations. Environ. Politics 23, 376–394 (2014).

Stevenson, H. & Dryzek, J. S. The discursive democratisation of global climate governance. Environ. Politics 21, 189–210 (2012).

Willetts, P. From ‘consultative arrangements’ to ‘partnership’: the changing status of NGOs in diplomacy at the UN. Glob. Gov. 6, 191–212 (2000).

Death, C. Governing Sustainable Development: Partnerships, Protests, and Power at the World Summit (Taylor & Francis, 2010).

Eweje, G. Strategic partnerships between MNEs and civil society: the post-WSSD perspectives. Sustain. Dev. 15, 15–27 (2006).

Morton, K. The emergence of NGOs in China and their transnational linkages: implications for domestic reform. Aust. J. Int. Aff. 59, 519–532 (2005).

Lövbrand, E., Hjerpe, M. & Linnér, B. Making climate governance global: how UN climate summitry comes to matter in a complex climate regime. Environ. Politics 26, 580–585 (2017).

Andresen, S. in The Handbook of Global Climate and Environment Policy (ed. Falkner, R.) 304–319 (John Wiley and Sons, 2013).

Helm, C. & Sprinz, D. Measuring the effectiveness of international environmental regimes. J. Confl. Resolut. 44, 630–652 (2000).

Mitchell, R. B. (2008) in Institutions and Environmental Change: Principal Findings, Applications, and Research Frontiers (eds Young, O. R. et al.) 83–84 (MIT Press, 2008).

Chan S. & Mitchell, R. B. in Agency in Earth System Governance (eds Betsill, M. M. et al.) Ch. 14 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2020).

Young, O. R. Effectiveness of international environmental regimes: existing knowledge, cutting-edge themes, and research strategies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 19853–19860 (2011).

Widerberg, O. & Stripple, J. The expanding field of cooperative initiatives for decarbonization: a review of five databases. WIREs Clim. Change 7, 486–500 (2016).

Szulecki, K., Pattberg, P. & Biermann, F. Explaining variation in the effectiveness of transnational energy partnerships. Governance 24, 713–736 (2011).

Chan, S. et al. Climate ambition and sustainable development for a new decade: a catalytic framework. Glob. Policy 12, 245–259 (2021).

Abbott, K. W. Orchestrating experimentation in non-state environmental commitments. Environ. Politics 26, 738–763 (2017).

Cashore, B., Bernstein, S., Humphreys, D., Visseren-Hamakers, I. & Rietig, K. Designing stakeholder learning dialogues for effective global governance. Policy Soc. 38, 118–147 (2019).

Dubash, N. K. Revisiting climate ambition: the case for prioritizing current action over future intent. WIREs Clim. Change 11, e622 (2020).

UNFCCC/Marrakech Partnership for Global Climate Action (UNFCCC, 2016).

Chan, S., Brandi, C. & Bauer, S. Aligning transnational climate action with international climate governance: the road from Paris. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 25, 238–247 (2016).

Bulkeley, H. et al. Transnational Climate Change Governance (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Widerberg, O. & Pattberg, P. International cooperative initiatives in global climate governance: raising the ambition level or delegitimizing the UNFCCC? Glob. Policy 6, 45–56 (2015).

Rogelj, J., Forster, P. M., Kriegler, E., Smith, C. J. & Séférian, R. Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate targets. Nature 571, 335–342 (2019).

Climate Action Tracker (Climate Analytics & New Climate Institute, 2020); www.climateactiontracker.org

Höhne, N. et al. Emissions: world has four times the work or one-third of the time. Nature 579, 25–28 (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, in press).

Abbott, K. W. The transnational regime complex for climate change. Environ. Plan. C 30, 571–590 (2012).

Gordon, D. J. & Johnson, C. A. The orchestration of global urban climate governance: conducting power in the post-Paris climate regime. Environ. Politics 26, 694–714 (2017).

Chan, S., Ellinger, P. & Widerberg, O. Exploring national and regional orchestration of non-state action for a <1.5 °C world. Int. Environ. Agreem.-P. 18, 135–152 (2018).

Tosun, J. Collective climate action and networked climate governance. WIREs Clim. Change 8, e440 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research received support from Volkswagen Stiftung, grant no. A137201 (T.H, S.C, K.M. and V.C) and the Klimalog project at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS), funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) (A.D.). We thank J. Brehm, M. Garcia, M. Gütschow, B. Nimshani Khawe Thanthrige, M. Mohan, B. Nagasawa de Souza, S. Pfund, S. Posa, A. Teunissen, E. Tingwey and M. Whitney for their support in data collection and the continued development of C-CID.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) gGmbH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.H. and S.C. conceived and designed the study and wrote the manuscript. T.H., S.C. and A.D. collected and validated data and produced figures. T.H. and A.D. conducted statistical analysis. A.D., M.S., K.M., V.C. and J.A. contributed to writing the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Bjorn Ola Linner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussion, Sections I–IV, Tables 1–12 and Fig. 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, S., Hale, T., Deneault, A. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of orchestrated climate action from five years of summits. Nat. Clim. Chang. 12, 628–633 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01405-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01405-6

This article is cited by

-

Synergy of climate change with country success and city quality of life

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

International bureaucrats’ attitudes toward global climate adaptation

npj Climate Action (2023)

-

The impact of climate summits

Nature Climate Change (2022)