Abstract

This study aims to examine the relationship between various subcultures present in a higher education institution and the facilitation and realisation of academic quality criteria. Via a qualitative ethnographic approach consisting of in-depth interviews, observations and document analyses of a single higher education institution, it presents evidence of a type of subgroup (termed the quality subgroup) that has emerged in the targeted academic programmes. This quality subgroup has a positive impact on accomplishing academic quality criteria. In the same vein, the study highlights other types of subgroups that have a negative impact on such criteria. The findings underline a range of theoretical implications relating to organisational culture, subcultures and culture-quality theory and methodology. They also present a range of practical implications, most importantly, how the quality subgroup members work on quality standards and how they succeed in listing their academic programmes for academic accreditation. Finally, the findings of the study shed light on vital features and changes in the Saudi higher education institutions’ working environments (due to critical legal and social changes) that contribute to cultural studies and human resource practices in Saudi organisations. Such practical implications are argued to advance higher education institutions’ policies and management. A comprehensive discussion of the study theory and practical implications is included in the conclusion section.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Interest in academic quality in higher education institutions (HEIs) has noticeably increased in the last few decades (Ehlers, 2009; Bendermacher et al., 2017, 2019). Contemporary literature reviews attribute this increase to the effective economic and social roles that HEIs play in the modern era (Dzimińska et al., 2018; Ardito et al., 2019; Budiharso and Tarman, 2020). However, governments and other social institutions have raised concerns over the efficiency of HEIs processes and the effectiveness of their outcomes, especially those that receive public funds or societal donations (Bendermacher et al., 2017, 2019).

Thus, certain governments, and other societal institutions, rely on specialised institutions to assess the quality of HEIs (e.g. Research Excellence Framework, Times Higher Education, Quacquarelli Symonds and Shanghai Ranking Consultancy) to determine where to direct their funding (Hosier and Hoolash, 2019). These factors have caused HEIs to invest in organisational change processes, where management and academic quality standards (as identified by HEI ranking institutions) are often at the forefront of their strategic plans, enabling them to meet HEI ranking standards (Sutic and Jurcevic, 2012).

Saudi Arabia is no different in this respect from many other countries, placing their HEIs at the centre of their economic and societal aspirations (see Mousa and Ghulam, 2019). The Saudi government now recognises the value of academic quality in its HEIs and the influence of such quality on their outcomes. Consequently, a national project was established in 2004 to assess the management and academic quality of HEIs. This project is known as the National Center for Academic Accreditation and Assessment (NCAAA) (Education and Training Evaluation Commission, 2021a).

However, due to the complex structure of HEIs and their faculty (see Cameron and Freeman, 1991), it seems that applying academic quality criteria to such institutions is fraught with several challenges (see Cardoso et al., 2016; Bendermacher et al., 2017, 2019; Tight, 2020). Indeed, Saudi HEIs—as an example—offer more than 1500 different academic programmes; however, statistics indicate that only 180 programmes have thus far gained NCAAA accreditation (Education and Training Evaluation Commission, 2021b). To overcome such challenges, different studies have emphasised the role that organisational culture (OC) plays in enhancing academic quality in HEIs (Harvey and Stensaker, 2008; Bendermacher et al., 2017). They highlight that enforcing ‘quality values’ among members and managing/controlling other aspects of OC may facilitate the management of quality changes and the application of standards.

Nevertheless, reviews on OC highlight significant debates regarding the effectiveness of the concept of ‘controlling culture’ and how it affects other aspects of an organisation, such as quality culture (see Willmott, 1993; Alvesson and Spicer, 2012; Fleming, 2013). In addition, organisations are comprised of different subcultures that influence the natures of their workplaces. It is also worth mentioning that only a few studies covered the associations of subcultures in the Saudi context (e.g. Aldhobaib, 2017), although organisational studies are emphasising that national culture, and other personal characteristics, may have influences on OC (see Bolman and Deal, 2017; Ogbonna, 2019; Aldhobaib, 2020). Indeed, Aldhobaib (2017) and Subbarayalu et al. (2021) highlighted that the Saudi organisational environment differs from other countries in that religion and some social traditions may have direct influences in the workplace (e.g. the separation between males and females in the workplace). However, despite the ongoing criticisms of the assumption that OC can be directed to achieve management desires, and the empirical proof that subcultures have considerable influence over the work environment, only a few studies have taken this into consideration when examining the influence of subcultures on quality in HEIs (see Bendermacher et al., 2017).

Due to this lack of focus in previous studies, this present research aims to investigate the following main research questions: (a) what is the reality of the environment within colleges and academic departments, and are subgroups affecting management tasks; (b) what are the roles of subgroups in facilitating quality standards; and (c) how do subgroups accomplish NCAAA standards and succeed in listing their academic programmes for NCAAA accreditation?

The examination of these study questions may contribute to theoretical and empirical knowledge by discovering the realities of the Saudi higher education environment as well as examining subcultures in HEIs, the nature of their emergence and their interactions with academic quality criteria. More specifically, this study examines these issues from a more wide-ranging perspective to investigate management interactions and actions taken behind the scenes before an academic programme is accepted for accreditation. It interprets the impacts of ‘quality subcultures’ (a group formed due to their focus on accomplishing accreditation standards) on the facilitation of quality management changes and how they may emerge in other HEIs. Hence, by tracking the management activities of academic programmes that apply the NCAAA accreditation standards (it was designed for all academic programmes; Education and Training Evaluation Commission, 2021a) and analysing the interpretations of their members, this would achieve the aims of the study and answer its questions.

Literature review

Although OC has been extensively researched in contemporary organisational theory and practice, several aspects of the concept remain debatable (see Martin and Frost, 2011; Aldhobaib, 2020). Nevertheless, it should be indicated that the purpose of this review is not to investigate these issues in detail, but rather to emphasise the value of the subcultural approach in examining the role of subcultures in meeting academic quality criteria in HEIs.

Definition of OC

The definition of OC remains a problematic issue in literature; reviews show no firm agreement on its meaning nor how it should be analysed. Nevertheless, key reviews and research on OC indicate that Edgar Schein’s definition provides a broad understanding of the concept and how it can be analysed (Martin and Frost, 2011; Aldhobaib, 2020). Accordingly, this study defines OC as “the set of shared, taken-for-granted implicit assumptions that a group holds and that determines how it perceives, thinks about and reacts to its various environments” (Schein, 1996, p. 236).

The significance of this definition is that it considers OC as a ‘negotiated order’. This means that OC is not merely inspired by organisational everyday activity, it is also influenced by the power of various groups and individuals to set the agenda for such activity. Another implication is that OC has physical and cognitive components, where the cognitive elements are inherited in the form of beliefs, values and underlying assumptions that, in turn, lead to interactions with the physical items in the workplace (Schein, 2010; Ogbonna and Harris, 2015; Aldhobaib, 2020).

Finally, this definition underlines the fact that identifying consistent values in large organisations is close to impossible (Gregory, 1983; Meyerson and Martin, 1987; Martin and Frost, 2011). This statement increases the significance of researchers’ suggestion that future studies should focus on discovering the values that characterise a single organisation and examining how those values interact with management and quality aspects (Harvey and Stensaker, 2008; Venuleo et al., 2016; Bendermacher et al., 2017).

Approaches to analysing OC

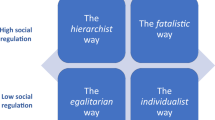

Similar to the definition of culture, OC reviews show variations in their approaches to analysing OC (e.g. Martin and Frost, 2011; Alvesson, 2013, 2016; Aldhobaib, 2020). While some studies view culture as the ideational system of the whole organisation that can be controlled by organisational leaders, other studies view it as multiple cultures that have mutable beliefs, values and underlying assumptions that exist simultaneously in any given organisation (Hopkins et al., 2005; Ogbonna and Harris, 2015; Ogbonna, 2019). This debate can be traced to the ontological and epistemological preferences of researchers, as succinctly outlined in Smircich’s (1983) classification of how culture is conceptualised.

Some scholars claim that culture should be viewed in material terms and, therefore, is subject to control (e.g. Peters and Waterman 1982). Others—who take a more social position—argue that culture should be considered as a cognitive manifestation of an organisation, which is loosely controlled by conscious action by those in authority (e.g. Legge, 1994). This debate has created three distinct but key assumptions in OC literature: (a) organisational leaders can unify OC and direct it to their desires; (b) organisations have multiple subcultures that are influenced by different employees, and only a few subcultures are subject to direct control; and (c) OC is vague and it cannot be managed (Martin and Frost, 2011).

Several studies that focus on unified/control culture assume that OC equates to ‘power’, and therefore, organisational leaders can create it and direct it to achieve explicit and implicit organisational goals (Ogbonna, 1993). This is achieved by enforcing—and reinforcing—certain values that, within time, are adopted by employees (Martin and Frost, 2011). Unsurprisingly, these claims have received noticeable criticisms (Willmott, 1993; Alvesson and Spicer, 2012; Fleming, 2013).

A pivotal issue that OC reviews highlight is that such studies are constructed based on snapshot accounts (Denison, 1996). This restriction has caused certain organisational scholars to argue that such studies concentrate on only a few visible cultural manifestations (i.e. values and norms) that are analysed by quantitative methods, instead of analysing wider and deeper manifestations (i.e. assumptions) using qualitative methodologies (Denison, 1996; Schein, 2010). These studies assume—sometimes without adequate evidence—that cultural manifestations are consistent with each other; and thus, a single manifestation would reflect the OC as a whole (Martin and Frost, 2011; Chatman and O’Reilly, 2016). Nevertheless, many OC scholars have disproved this claim, showing that the meaning associated with a single cultural manifestation may not be consistent with the meaning associated with other manifestations. Thus, following this erroneous belief may generate deceptive data (Schein, 2010; Martin and Frost, 2011; Alvesson, 2013, 2016).

These studies also assume that managers are the main players in creating OC. This assumption has led to the criticism that such studies neglect—either by denying or ignoring—the roles of other managerial levels, such as lower-level employees (Alvesson, 2013, 2016). Related to this is the fact that these studies exclude the existence and influence of subcultures and individual resistance from their analyses; they claim that they are signs of a weak culture (Schein, 2010).

Alternatively, multiple empirical research provides evidence that subcultures exist in organisations and that they play influential roles in the workplace (Van Maanen, 1991; Kunda, 1992; Ogbonna and Harris, 2015). Indeed, Bolman and Deal (2017) provide a case of a computer development team that shows how leaders and group members jointly created a subculture that tied people together to achieve a shared mission. It highlights that group stories, ceremonies, specialised language, humour and irony can all combine to convert varied individuals into a unified subgroup with purpose, spirit and soul. Such issues are critical in supporting the concerns of the recent study, its analysis and its contributions.

Culture-Quality studies in HEIs

Contemporary literature reviews on quality–culture relationships show that most studies have adopted the concept of unified culture in analysing OC and its associations with aspects of quality in HEIs (Ehlers, 2009; Bendermacher et al., 2017). Regardless of the ongoing criticisms levelled at this approach, these studies continue to assume that organisational leaders can create a unified culture and that organisational values can represent the OC as a whole (e.g. Yorke, 2000; Lycke and Tano, 2017; Hildesheim and Sonntag, 2020). They also neglect the emphasis that national culture and personal characteristics (e.g. gender, social background, education, race, seniority, etc.) may have influence on building subculture(s) within an organisation (Chatman and O’Reilly, 2016; Bolman and Deal, 2017; Aldhobaib, 2020). These limitations increase the significance of conducting empirical studies that examine the relationship between subcultures and quality in HEIs (Harvey and Stensaker, 2008; Ehlers, 2009; Bendermacher et al., 2017).

However, subculture-quality research shares a similar problematic conception of unified culture research. Such research often claims that organisational values are representative of OC, and therefore, the difference between organisational values and subgroup values can reveal subcultures (Bendermacher et al., 2017). They explain, in addition to the justifications discussed formerly, that analysing the deep manifestations of OC is a difficult mission; requiring extensive effort and time. Hence, concentrating on the difference between OC and subgroup values can identify subcultures, and this enables a researcher to examine their associations with quality issues (Cameron and Freeman, 1991). Such limitations increase the significance of conducting an empirical qualitative study that analyses the broad manifestations of subcultures and how they interact with quality issues in HEIs.

Research design and methods

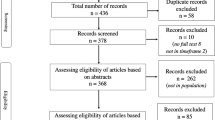

To serve the purpose of this study, five universities that had gained NCAAA institutional accreditation were identified and contacted to arrange the case study. Three of them were private universities and two were state universities. The private universities showed more concern than the public universities in how the researcher would collect the data and how it would be used. This is despite the fact that the research ethics were fully explained and guaranteed by the researcher. Hence, the options were reduced to two public universities.

After selecting the most suitable university between the two, all its academic programmes that had gained NCAAA accreditation, or had received a final visit by NCAAA examiners, were listed. Only five from a total of 160 academic programmes were identified. Four academic programmes across different colleges allowed the researcher to collect the data. Due to the confidentiality agreement in place for this research, participants were given different names and the academic programmes were given ranking codes based on their accreditation results: A1, A2, B, and C.

Data gathering

This study relies on an established ethnographic, qualitative approach comprising interviews, observations and document analyses of a single-organisation case study (Mathew and Ogbonna, 2009; Aldhobaib, 2020). The organisation studied is referred to here under the pseudonym ‘Century University’ and is one of 29 state universities in Saudi Arabia (Ministry of Education, 2020). Century University granted essential access to the researcher, which lasted between January 2020 and March 2021. This access included interviewing the university faculty, visiting its facilities and collecting relevant documents. Beyond the university strictly adhering to the confidentiality conditions laid out at the beginning of data collection, they were very generous with the time they allowed the researcher to spend interviewing the university faculty, observing their activities and viewing some of the university’s confidential documents.

The study began with data collection that involved visiting some of the university’s facilities to observe their formal and informal functions and to collect relevant documents, such as their manual on monitoring the quality of educational processes at the university, their system of quality management and academic accreditation, and regulations of state university affairs that had been established by The Ministry of Education. This stage continued for the rest of the data-gathering period; it was necessary to generate a general view of the university’s history and culture and validate the claims of the university members about the OC and subculture issues (Ogbonna and Harris, 2015; Aldhobaib, 2020).

After around 4 weeks, unstructured interviews were conducted with 11 high-level officials. Using the information analysed from the former step, they were asked broad questions about the history of the university, the changes that occurred recently and the issues that would differentiate it from other universities. Around 3 weeks were spent on this step to gain an insight into the general culture of the university (the wider organisational cultural assumptions, beliefs and values) and the history of its management changes. This step provided several advantages to the study. Most importantly: (a) participants provided several insights that were used in the Case Background section; (b) participants shed light on the emergence of academic department subgroups; (c) participants highlighted the academic programmes that had received a final visit from the NCAAA examiners; and (d) participants offered the researcher vital connections to the head of targeted academic departments and other key members, which significantly facilitated the data collection process. Table 1 summarises the interview factors and essential characteristics of its participants.

After interviewing high-ranking officials, the rest of the data gathering time was spent conducting semi-structured, private, face-to-face interviews with members of the targeted departments. The data gathered from observations, document analyses and interviewing high-ranking officials assisted in devising questions for these semi-structured interviews. Participants here exposed a range of critical issues. Most significance: (a) their interpretations of the existence of different subgroups within a college/academic department; (b) how quality subgroups emerged within academic departments, the values their members held and how they were defined and differentiated from other members of the same college; and (c) the differences that occurred within the targeted department and their consequences for inter and intracultural relations.

All interviews, barring six, were audio-recorded, the exceptions being mainly those with high-level employees who asked that they be exempt from recording. These interviewees, however, allowed the researcher to take notes. The interviews lasted between 40 and 100 min, on average, and were all transcribed verbatim. The questions in the semi-structured interviews were open-ended; maximising the opportunity for participants to illustrate the reality of their work in their own language, using their own terms and jargon (Ogbonna and Harris, 2015; Bolman and Deal, 2017; Aldhobaib, 2020). It is also worth highlighting that the inclusion of such a wide dataset of interviewees negated the potential for bias. This is because numerous, highly qualified and knowledgeable participants were able to provide a broad range of opinions and perspectives on the research targets (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007).

Regarding observations, the researcher was allowed to attend various meetings during the data gathering and granted access to different colleges and academic facilities. This included observing training sessions that the university provided to employees who work on NCAAA accreditation (which frequently contained ‘heated debates’ regarding the essential support that the university should provide to its staff) and attending some final visits by NCAAA examiners (where the researcher witnessed the activities and interactions of staff at close proximity).

Data analysis

This study used electronic research notebooks to record data that were collected from document analysis, the notes taken from the unrecorded interviews and the extensive series of observations. The data were combined with the verbatim transcripts of the audio-recorded interviews to facilitate data analysis. All data were reviewed regularly, which assisted the researcher in linking events and perspectives and finding explanations for multiple unjustified actions and decisions. This required the researcher to revisit some of the university’s facilities, reconnect with already interviewed participants and interview new members.

Following the suggestions of Strauss and Corbin (1998) on grounded theory, the data analysis applied a systemic approach (i.e. open, axial and incorporated selective coding). Open coding was initially used to explore and classify patterns and dimensions of concepts in the data. Following this, axial coding was used to create themes that linked similar core patterns and dimensions. Finally, selective coding was applied to subdivide themes into coherent theoretical groups.

Study analysis

Case background

It is essential to provide a broad overview of the organisation under investigation. This will shed light on critical factors and changes that have implications for the university and the emergence of subgroups within academic departments. It will also underline fundamental social factors and other social changes that have influenced the work of the university.

Century University is one of four state universities established to provide Islamic academic programmes (or ‘Islamic science’). This includes Sharia law, Arabic and other related subjects in the humanities (e.g. Islamic Economics). However, due to sharp population growth—especially among youth—(see Saudi General Authority for Statistics, 2020) and the excellent infrastructure of these universities, the government decided to expand academic programmes to other areas, such as medicine, engineering, computer science and other business subjects. This decision, as the data collection detected, created opposing views that have had major effects on all formal and informal functions of the university. Some argue that the core of this university’s work is teaching and developing Islamic programmes; thus, other ‘non-Islamic’ universities may focus on non-Islamic programmes.

In the same vein, others emphasised that Islamic science is ‘Semitic’ and should not be mixed with other ‘positive’ sciences. Others disagreed with such an assumption and believe that there is no such ‘Islamic science’ that relies on the established methodologies of ontology and epistemology. Due to these conflicting views, academic departments are divided into implicit and explicit subgroups, and this was considered to be the first sign that academic departments contained multiple/counter subgroups.

Another related issue regarding Century University is the recent change in its leadership. As the data analysis reflects, this has created a chain of changes in different functions, including the academic quality regulations. An important implication of the leadership change is the revision of the university’s budget for academic programmes. The university also worked on redesigning certain units to maximise their efficiency. The downside of these steps has been that the university reduced funding to existing academic programmes, including some that were working towards NCAAA accreditation. These, as will be discussed shortly, have created several challenges for serving the purpose of NCAAA accreditations.

In terms of the structure of quality, it is rather complex (see Fig. 1 for a helpful graphic). However, it is worth highlighting that the fundamental role of all quality position tasks (except that of the academic department) is technical support and overseeing quality work done by the academic department team. This means that the core of academy quality relies on the management of the academic departments, the collaboration of their members and—most significantly – the Subquality Committee members, who are responsible for fulfilling all the NCAAA criteria that lead to accreditation. The data analysis indicates that failure to achieve NCAAA standards was mainly due to the poor formation of subquality committees; the members do not share mutual values that could otherwise drive their efforts towards quality work. In short, the subquality committees, despite being but a small cog, leverage the entire bureaucratic machine.

Another relevant point is that Century University used to have a total separation between males and females (academic staff, managerial staff, students, etc.) (see Aldhobaib, 2017, pp. 82–97 for further explanation of Saudi social and work issues). However, these separation restrictions started to loosen due to reforms that the Saudi government recently enacted in this regard (Saudi Unified National Platform, 2021). The circumstances of these reformations will be reflected in the following subsections.

The reality of academic departments

Multiple subgroups

Data analysis shows that the targeted academic programmes had engaged in necessary management change processes in the last 2–3 years to meet NCAAA standards. Data analysis revealed that the NCAAA accreditation journey involved three main phases: (a) emergence of quality subgroups; (b) quality subgroups taking the lead to work on quality; and (c) quality groups maintaining quality gains.

A notable issue found here is that the management change processes caused the creation of both active and inactive subgroups that had significant impacts on quality work. Some of these subgroups supported quality group work, believing in continuous improvement and educational excellence, whereas others showed strong resistance to the tasks that quality groups requested and the culture that they attempted to promote.

Interesting contra groups that existed in A2, B and C are known as ‘old-times’. Its members were described as ‘traditional’, preferring traditional teaching strategies and refusing new techniques emphasised by NCAAA standards. Abdullah (a C quality member) noted the following:

The ‘old-timer’ group harmed the accreditation processes. They prefer typical teaching strategies, just reading and explaining the content of a textbook, which they have been using for a long time. They did not want to use the syllabus or pay real effort to achieve the learning outcomes that were set up for their modules [mentioned other quality requirements]. Dealing with this group slowed down quality progress and delayed the NCAAA accreditation.

Another example of the contra subgroups is known as the ‘gurus’, who assume that they are experts in teaching and learning processes and know what is better for their students. Omar (a quality member at A2) highlighted some issues that characterised this group:

There is a group that resisted the accreditation standards for a while due to some characteristics they have. First, they are relatively older, which made them claim that they know everything related to teaching and learning issues… and thus they used to argue that NCAAA standards are a waste of time and effort. The other characteristic, which I could not understand, is they assume the college must consult them in any changes that it would make, since they were ‘the experts’, and should not be guided by those quality members.

The data gathering and analysis indicate that most colleges have the same, or at least similar, types of subgroups. The only college that did not show evidence of such subgroups was A1; participants explained that the environment of the college was relatively new, and therefore, members were more open to change and improving their own environments.

The emergence of quality subgroups

Data analysis reveals that quality subgroups emerged when colleges started signing contracts with the NCAAA, and it also shows that they have had an effective impact on work towards quality. Different participants emphasised that the regulations of academic work and affairs advanced after the quality group started their mission:

The academic works before the quality standards were random. There was no clear plan or guidance on how you start a module and how you end it. Sometimes, you found a group of instructors teaching the same module in different styles. But, after we made the contract with the NCAAA, things started to change gradually. Today, quality standards involve every teaching process and programme management task. Every instructor now knows what to do in their modules and how to improve the weaknesses they discover, or are given by the quality group, in the next semester (Sami, quality member at B).

The most interesting group emerged in A2. They showed distinctive characteristics and applied unique approaches to achieving quality work. This group developed in the female sections, where quality work is led by female members. This was different from other colleges under investigation, where quality groups developed in the male sections (as with the deanship) and quality work is mainly led by male members.

Different participants explained that the establishment of the A2 subgroup was influenced by a highly respected member among the A2 group with a visionary approach that inspired female members to join or interact positively with quality work:

We have an inspirational member that made miracle changes in [A2], who is [her name]. Since day one, she never stopped encouraging us to present the excellence of our college and what it teaches through applying the quality accreditation strictures and listing the college in the NCAAA accreditation, where it belongs (Anood, A2 female quality member).

Multiple participants showed that the vision of the head team (which will be highlighted further in the following sections) succeeded in inspiring other members to accomplish accreditation tasks, regardless of the challenges that they faced during the accreditation journey:

When I joined the accreditation team [quality group], [mentioned the name of the female member] was leading the work and her passionate vision that was making the college among the top. This has encouraged us to go beyond what the accreditation required. She has created a different atmosphere that the college has never experienced. When we [members of the quality group] face depressive moments, which has happened many times because of careless members who delayed quality tasks, or an official who did not give quality priority, you find her next to you asking you to think about the ultimate goal [increasing the position of the college]. This always changes everything, and it always gets us back to our mission (Aisha, A2 female quality member).

Interestingly, the findings reveal changes in the role of Saudi female employees and how they may effectively impact quality work. The communication and interaction between male and female employees in this organisation have recently increased to the point where many participants assumed that female employees may lead quality work in the future. Many participants expressed the view that female employees are more determined and precise in quality work than males; however, this should be investigated in more detail, as the data gathering was not purely focused on female employees’ interactions with quality work.

Taking the lead on quality and programmes

This section of the study reflects the functioning of quality groups, their interactions with accreditation standards and how they succeeded in gaining NCAAA accreditation. The conversations that took place in quality training sessions and workshops underline that most quality groups failed to take primary steps towards accomplishing accreditation standards at the beginning of their mission. This was attributed to the high-level resistance and the negative influence of other dominant groups (e.g. old-times).

Recruiting new members to join quality groups

Quality groups, especially in A2, B and C, stated the need for other members to support advanced quality work, as Anood describes:

When we started the accreditation journey, there were only a few who really cared about quality and accreditation standards. Some used to say, ‘what is quality?’, ‘why do they keep throwing tasks on us?’ and ‘why should we be bothered?’ But this has changed. We started using every gathering, workshop and meeting to recruit new members and convince them about the importance of quality standards to all programme stakeholders. Thank Allah [God]. This has changed quality work for good, especially during the time before the NCAAA examiners visited us (female quality member at A2).

C quality members prepared induction programmes that targeted those who had just joined the department and ran sessions related to quality work, accreditation standards and how to carry out related tasks. Although new members to the group showed no resistance to their new work, most existing members highlighted that these steps would make new members immune from negative thoughts that contra subgroup members may pass to them, as Abdullah illustrated:

We also welcome every member who joins the department. We give them an induction session that stresses the importance of quality and how to apply its standards. So, we stop poisoned thoughts [of other groups] from coming first to them. At the same time, we try to be closer to them and follow up on their quality work; it is easier to train someone who has no negative background about quality than someone you need first to change his thoughts about how modern academic work should be (C quality member).

Another point worth noting from the data is that quality groups have learned the advantage of recruiting members who have specific personal characteristics. They illustrate that such members have a positive effect on quality work and that they were mainly recruited to occupy positions within quality groups. Participants highlighted fairly common desirable characteristics (e.g. committed, determined, flexible, organised, passionate, etc.), but also certain unusual characteristics (i.e. having diplomatic skills, patience, and social intelligence).

Mai (a female A2 quality group member) explained how social intelligence aids quality work and supports their group:

Interviewee: Among the mistakes we made is recruiting some quality officials that did not know how to manage things in smart ways, I mean using ‘social intelligence’. They tended to confront others, opening unnecessary battlefronts and forcing members to submit quality work without understanding the soul of ‘quality’ [that members should be convinced about quality tasks to provide real data about their work and contribute to the continuous improvement that quality standards emphasise].

Interviewer: How did you solve this challenge?

Interviewee: Among the things we tried is increasing ‘friendliness’ aspects among department members. This reduced tensions, especially when we asked members about the many quality tasks. For example, we have a friendly gathering at the beginning and end of every semester, where we serve tea and coffee [these two drinks symbolise hospitality and friendship in the Saudi community], and we encourage making friendly conversations. When we feel the atmosphere is smooth, we pass pre-planned messages about the importance of our mission and the importance of quality for the department stakeholders.

Regarding diplomatic skills, several participants from different quality groups indicated they are necessary to attract other members’ attention and concentrate efforts on fulfilling accreditation standards. Here is one indicative example:

We attracted those who have time management skills and members who were not rigid but had inner determination and showed a strong spirit of work improvement. We especially attracted those who were non-confrontational persons because quality works were forked and needed the commitment of different people from different units. So, we were looking for those who had diplomatic skills to deal with such people in different units (Husain, quality member at B).

Regarding patience, participants underlined that such a trait is essential; quality personnel should deal with daily obstacles without complaining about them to other members of the department to maintain a positive atmosphere:

The issue of quality work is endless, so are work problems. So, we learned that a quality member should be highly organised, determined and precise. We also learned that quality members should be wise and patient because work results would not appear immediately. Patience prevents quality members from getting bored, although they might get upset about the delay in submitting quality requirements or the negative reactions that they might receive from some members of the college (Khalid, quality member at C).

These findings suggest that certain personal characteristics may have correlations with subgroups and quality work. However, it cannot be certain whether such characteristics are a good fit for quality work in HEIs only or whether they may also suit such work in other complex work environments. In other words, due to the high level of organisational bureaucracy in state universities, members may be required to have such characteristics, which may also fit other public organisations.

Involving leaders in quality

All quality groups understood that without involving leaders of the college (i.e. the dean, vice deans and heads of department) in quality work, they would not make significant progress towards accreditation because quality group members had no authority over other members of the department whose collaboration was necessary to fulfil accreditation aims. Accordingly, they relied on two strategies to prompt leaders to be supportive of quality work.

The first strategy was to involve leaders in the quality group by pushing leaders to make the final decisions regarding quality work. Participants provided several examples of this, with the most noteworthy being the signing off on quality topics to be discussed in the department council. This also caused the quality work to appear legitimate and highly important:

Interviewee: Accreditation tasks were varied, and while some members collaborated with us [at the beginning of the accreditation mission], others resisted quality work.

Interviewer: How did you deal with this issue?

Interviewee: We sought the head of department’s collaboration. We suggested some names to the head of the department to be responsible for the subquality committees, and we asked him to appoint them to the council, so all council members know that they were appointed by the head of the department. We also asked the head of the department to discuss the delay in submitting the course reports, and we also listed all of those who submitted excellent course reports and asked the head of the department to give them awards. Such steps have encouraged members to work positively with quality work and have reduced resistance considerably (Ibrahim, quality member at B).

The other notable strategy was influencing the nomination of the college leaders. Participants of all colleges under investigation explained that they somehow recommended names from quality groups (or names of those who were interested in quality work) to leaders of colleges to be appointed to leadership positions. This has remarkably accelerated quality work and minimised challenges, as Yosif indicates:

The former dean was a quality guy [he established quality groups], and he was the dean and the head of the department at the same time. While we were working on [mentioned a name of another international accreditation], he asked me to be responsible for the NCAAA. I agreed, so he nominated me to be the vice-dean of quality. This step made quality a priority, where all members’ efforts were focused on the two accreditations at the same time (high-ranking member at A1).

Participants of A1 revealed that this step effectively empowered quality group work, where department members gathered and created a sophisticated computer system that facilitated quality work for department members. This system has received multiple awards from the college and university officials.

Enforcing quality culture

Participants emphasised the importance of what they called ‘quality culture’ that emphasised continuous improvement for facilitating quality work (i.e. one of the main values they shared). They explained that quality culture had been encouraged via different approaches, such as rewarding excellence, enforcing quality values during formal and informal gatherings and spreading quality slogans in departments and across colleges.

While all quality groups applied such techniques to encourage quality culture, two groups applied additional, more unusual techniques for encouraging quality culture, which assisted such work. A2 and B quality groups inspired members of their departments to interact with quality work by linking it with academic disciplines. This helped both groups to overcome difficulties such as member resistance and lack of collaboration.

Members of B showed that their emphasis on the notion that their programme should be the first listed in NCAAA and the first to apply quality standards encouraged members to work on accreditation tasks and empowered quality culture, as Nora illustrated:

Quality always takes a huge part of our meetings, such as the department council. We always repeat that our programme will be the first listed [in the NCAAA] in the entire Kingdom, and this somehow encouraged members to work more, especially junior instructors. Members became more interested in quality and how to apply its standards. They even started attending workshops we organised [the quality group used to complain about the lack of attendance] and asking relevant questions like, ‘how to apply better teaching strategies’ and ‘how to improve my teaching style’, all of which enabled the spread of quality culture (female quality member at B).

However, the A2 group applied the most unique strategy to encourage quality culture and advance quality work. This culture was inspired by the vision of the head of the female group, who challenged the implicit norm of the college: that its programmes focus on Islamic teachings. The perception was that Islamic sciences are ancient and Semitic and, therefore, do not need (positivist) relatively new criteria to prove their quality. While the A2 group approved of this view, they argued that the NCAAA standards improved and ensured the quality of management and teaching procedures, not the science itself. They believed that this would boost the experiences of both instructors and students.

Due to the focus of the A2 academic programmes, the group used certain Islamic concepts for implementing the NCAAA standards. For example, they emphasised the reward that Allah [God] gives to those who teach Islam and transfer its knowledge to the next generation with high-quality standards. They frequently support their claims with verses from the Quran and from the Prophet Muhammed’s speeches ‘hadith’, such as: ‘Allah will raise those who have believed among you and those who were given knowledge [i.e. Islamic knowledge], by degrees’ (Qur’an 58: 11). The group also used Islamic terminology and concepts to support quality culture and its practices (e.g. ‘Allah [God] appreciates those who do their work perfectly’ and ‘Islam means perfection’).

Nevertheless, among the many concepts, the A2 group stressed, they focused on the concept of ‘volunteering’ most strongly. Participants indicated that the concept of volunteering was suggested by the head of the female quality group and that it positively affected their quality of work and culture. Data analysis reveals several examples related to this matter. For instance, as Mohammed, shows:

The concept of volunteering started in the female section, and it has spread over to the male section. It has helped a lot, especially when the university stopped funding some of the quality initiatives. Sometimes we needed someone to collect data about the courses and their results and there was no budget for it. So, we had no option but to say do it voluntarily […] or work in this committee voluntarily, and we found high responses by members.

The approach that A2 applied indicates that Islamic values (whose followers believe that it is an approach to life) may have positive effects on Muslim employees. Indeed, some participants from other groups stressed Islamic values that have affected their work performance (e.g. integrity, devotion and mastery. However, the data could not link these values to their groups as they were stressed by some members of the groups only. Thus, the question of whether stressing certain Islamic values enhances Muslims’ work performance remains unanswered. Studies that investigate this issue in the future may thus advance the theory and practice of organisations.

Post-accreditation

Quality groups in all colleges under investigation recognised that, after their programmes had been listed in the NCAAA or they had received the final visit by NCAAA examiners, certain members of their departments tended to become lax regarding quality tasks. This caused some concern that the drive for quality could be lost. Therefore, data analysis observes that key quality members applied two core strategies to maintain quality work, as illustrated by the following sub-sections.

Keeping quality work ‘alive’

Several participants indicated methods of maintaining quality work such as preparing successors for quality committees, creating manuals for quality processes, organising ongoing workshops and ongoing discussion of quality issues during department councils. For instance, Nora highlighted that following up on quality tasks has maintained member enthusiasm, even after the programme was listed in the NCAAA:

Since the beginning of quality work, quality has been the aim of the department, not just the accreditation. So, we [quality group members] have kept the quality concept alive as we are still improving processes and infrastructure and discovering effective teaching strategies. Quality workshops never stopped, course reports are revised by quality subcommittees and there is close follow up by the quality subcommittees and the vice-dean for quality and head of the department. So, thank Allah [God] we kept everything as it is (female quality member at B).

Ali presents another example, as they were preparing successors for leading quality subcommittees and work:

Quality is an essential aspect today, so we [quality group members] kept this thought all the time. Thus, we are preparing the new head of the Quality Subcommittee, who will be trained [by the quality group] and will be ready after six months to take over quality tasks and not let the concept die (quality member at A1).

Rewarding work on quality

Data analysis indicates that quality members continued rewarding those who worked on quality tasks to maintain member motivation for quality work and secure their interest:

As professionals, we should continue rewarding those who sustain their performance on quality work and sacrifice their time and effort to improve the learning process. This gives clear messages that the accreditation was not the goal. The goal is quality. In fact, we do more than this; we make farewell to everyone leaving the department. We usually give them a shield of appreciation and invite them, and all members, to have dinner as one family. This shows all members, especially new members, that the department appreciates high-quality work (Yaya, quality member at A1).

Indeed, A1s focus on working as a family was acknowledged by the NCAAA examiners’ board. These actions helped the programme create a collaborative and friendly atmosphere that assisted them in overcoming many challenges and achieving two accreditations (international and NCAAA) in a short time.

C group also shared related sentiments, as Khalid noted:

After we finished the final visit by the NCAAA, the department organised a huge celebration in the college theatre. The aim, as was also confirmed by the head of the quality programme, was that accreditation is the means, not the end, where quality is the ultimate goal that should be kept in mind. The head of the department also emphasised the sacrifices of the quality group and that all members should work as one to continue quality work (quality member at C).

Finally, the B group revealed another approach for rewarding their members and advancing their quality work:

The department highlights distinctive work and those who apply distinctive quality practices in its WhatsApp group and Twitter account. This greatly encourages members and sustains their quality performance, like submitting course reports regularly, keeping improving teaching strategies and even giving training sessions about software programmes, like R and Blackboard (Sami, quality member at B).

The findings here draw attention to the extensive effort required by academic programme officials and members to continue their focus on quality after accreditation standards have been met. It is notable in the cases studied here that the quality aims go beyond the desire for accreditation in itself and that, by emphasising the significance of quality work through rewarding those who continue their high-quality performance, the quality groups and cultures that have been encouraged are more than sufficient to maintain the following up of quality tasks. Thus, similar HEIs should take note of these practices to encourage such a culture of quality across their institutions.

Conclusion and implications

The results of this study suggest a range of contributions and implications for theory and practice. The first contribution is linked to OC literature (specifically, unified OC research). The discussion of OC literature presented in this research determines attempts to control OC, where practitioner-oriented journals are replete with incredibly optimistic suggestions for such processes (Chatman and O’Reilly, 2016). However, such research is limited to theoretical critiques of simplistic management or studies.

The emphasis on widely shared values substantially underestimates the concept’s potential, which has led some to describe such studies as ‘stupidity management’ (Alvesson and Spicer, 2012) and others to even declare the end of ‘corporate culturism’ (Fleming, 2013). The findings of this study lend weight to these critiques as they emphasise the multiple values, beliefs and assumptions that might develop in multiple subcultures, where some could support an organisation’s mission statements and visions, and others may act against these goals. Analysing OC and its relationships with other work dimensions based on this fact should prompt revealing findings that may advance theory and practice.

The other contribution of this study is on culture–quality relation literature. The literature review shows that much culture–quality-related research relies on the unified culture concept, which causes the research to be subject to similar critiques as unified OC research. Quality–culture literature emphasises the enforcement of shared values and norms committed to quality (Bendermachera et al., 2017). However, consistent with findings from similar culture–quality relationship studies (e.g. Cameron and Freeman, 1991), the concept has critical limitations; notably, that HEIs members may be part of—and are affected by—different subcultures that may comprise various (sometimes opposing) values.

Analysing OC based on this logic enables studies to uncover different OC dimensions (i.e. subcultures) and their associations with essential work issues (e.g. quality). Nevertheless, it should be indicated that the current study is distinguishable from other similar studies in that it analyses all cultural manifestations, not only values and norms, and their relationship to quality work. This has provided deep insight into the role of subcultures and quality and how accredited academic programmes have met and maintained quality standards.

Another key contribution of this study is the insights provided into intra-subcultural relationships (Van Maanen, 1991; Kunda, 1992; Ogbonna and Harris, 2015; Bolman and Deal, 2017). The study’s inclusion of intra-subcultural relationships shows that a realistic understanding of intra-subcultural dynamics is vital if organisational/HEI leaders wish to assess OC or evaluate cultural change programmes effectively. The results of the current study show that the struggles quality groups face may lessen if qualified academic programme leaders can evaluate the OC (such as the opposing subcultures) and direct quality work. This could explain the failure of several academic programmes to fulfil academic accreditation standards.

The findings also prove the importance of recruiting and selecting personnel that have characteristics that are suited to their goals (not necessarily organisational values) and that have the capability to deal with potential challenges (Aldhobaib, 2020). Indeed, the personal traits that quality groups expressed in this study show how these traits have enabled them to overcome a variety of obstacles.

The final contribution of this study is that it is one of only a few that has evaluated OC via an ethnographic approach and uncovered numerous realities of Saudi organisations (Aldhobaib, 2017; Mousa and Ghulam, 2019). Most interestingly, this study has revealed an increase in the participation of female employees in Saudi HEIs (see Aldhobaib, 2017 for comparison). This may be attributed to two key factors: (a) the change of ‘conservative’ ideology that used to limit Saudi females’ participation to private life only (Saudi Unified National Platform, 2021) and (b) the recent initiative of the Saudi national vision that concentrates on increasing the participation of Saudi females in public life (Saudi General Authority for Statistics, 2020).

This highlights positive changes for Saudi female employees, but it also points towards the increased responsibility of these employees and their organisational leaders (Subbarayalu et al., 2021). To be more specific, female Saudi employees are still required to manage their private lives, whereas males’ responsibilities are traditionally constrained to protecting and providing for their families. In the same vein, most Saudi organisations (which find themselves required to employ Saudi females or give them leading positions) are not yet familiar with dealing with female employees’ affairs. These issues may create serious conflicts in Saudi female employees’ work–life balance, which could impact their private lives, work performance or both. Thus, further studies are required to understand the issues related to the increased participation of Saudi females in the workforce so that organisational leaders can understand their needs and desires as well as help them perform in the workplace.

Data availability

The data supporting the study’s findings are available upon request from the author.

References

Aldhobaib M (2017) The Relationship between organisational culture and individual behaviour in Saudi Arabia. PhD thesis, Cardiff University.

Aldhobaib M (2020) The Interaction between organisational culture and individual behaviour: a conceptual approach. Organ Cult 20:13–34. https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-8013/CGP/v20i02/13-34

Alvesson M (2013) Understanding organisational culture, 2nd edn. Sage, London

Alvesson M (2016) Organisational culture and work. In: Edgell S, Gottfried H, Granter E (ed) The SAGE handbook of sociology of work and employment. Sage, London, pp. 262–282

Alvesson M, Spicer A (2012) A stupidity-based theory of organisations. J Manag Stud 49:1194–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01072.x

Ardito L, Ferraris A, Petruzzelli AM, Bresciani S, Del Giudice M (2019) The role of universities in the knowledge management of smart city projects. Technol Forecast Soc Change 142:312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.030

Bendermacher GWG, Oude Egbrink MGA, Wolfhagen HAP, Leppink J, Dolmans DHJM (2019) Reinforcing pillars for quality culture development: a path analytic model. Stud High Educ 44:643–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1393060

Bendermacher GWG, Oude Egbrink MGA, Wolfhagen IHAP, Dolmans DHJM (2017) Unravelling quality culture in higher education: a realist review. High Educ 73:39–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9979-2

Bolman LG, Deal TE (2017) Reframing organisations: artistry, choice, and leadership. John Wiley and Sons, NJ

Budiharso T, Tarman B (2020) Improving quality education through better working conditions of academic institutes. J Ethn Cult Stud 7:99–115. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/306

Cameron KS, Freeman SJ (1991) Cultural congruence, strength, and type: relationships to effectiveness. Res Organ Change Dev 5:23–58

Cardoso S, Rosa MJ, Stensaker B (2016) Why is quality in higher education not achieved? The view of academics. Assessm Eval High Educ 41:950–965. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1052775

Chatman J, O’Reilly C (2016) Paradigm lost: reinvigorating the study of organisational culture. Res Organ Behav 36:199–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.004

Denison D (1996) What is the difference between Organisational culture and Organisational climate? A native’s point of view on a decade of paradigm wars. Acad Manag Rev 21:619–654. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9702100310

Dzimińska M, Fijałkowska J, Sułkowski Ł (2018) Trust-based quality culture conceptual model for higher education institutions. Sustainability 10:2599. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082599

Education and Training Evaluation Commission (2021a) About Education and Training Evaluation Commission. https://etec.gov.sa/en/About/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 21 May 2021

Education and Training Evaluation Commission (2021b) Accredited programs. https://etec.gov.sa/en/productsandservices/NCAAA/academic/Pages/ProgramsDirectory.aspx. Accessed 21 May 2021

Ehlers UD (2009) Understanding quality culture. Qual Assur Educ 17:343–363. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880910992322

Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME (2007) Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manag J 50:25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

Fleming P (2013) ‘Down with Big Brother!’ The end of ‘corporate culturalism’? J Manag Stud 50:474–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01056.x

Gregory K (1983) Native-view paradigms: multiple cultures and culture conflicts in Organisations. Adm Sci Q 28:359–376. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392247

Harvey L, Stensaker B (2008) Quality culture: understandings, boundaries and linkages. Eur J Educ 43:427–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00367.x

Hildesheim C, Sonntag K (2020) The quality culture inventory: a comprehensive approach towards measuring quality culture in higher education. Stud High Educ 45:892–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1672639

Hopkins WE, Hopkins SA, Mallette P (2005) Aligning organisational subcultures for competitive advantage: a strategic change approach. Basic Books, New York

Hosier M, Hoolash BKA (2019) The effect of methodological variations on university rankings and associated decision-making and policy. Stud High Educ 44:201–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1356282

Kunda G (1992) Engineering culture: control and commitment in a high-tech corporation. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA

Legge, K (1994) Managing culture: fact or fiction. In: Sisson K (ed) Personnel management: a comprehensive guide to theory and practice in Britain. Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 397–433

Lycke L, Tano I (2017) Building quality culture in higher education. Int J Qual Serv Sci 9:331–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-04-2017-0033

Martin, J, Frost P (2011) The Organisational culture war games: a struggle for intellectual dominance. In: Godwayn M, Gittell JH (eds) Sociology of organisations: structures and relationships. SAGE, London, pp. 315–336

Mathew J, Ogbonna E (2009) Organisational culture and commitment: a study of an Indian software organisation. Int J Hum Resour Manag 20:654–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190802707433

Meyerson D, Martin J (1987) Cultural change: an integration of three different views. J Manag Stud 24:623–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1987.tb00466.x

Ministry of Education (2020) State universities. https://www.moe.gov.sa/en/education/highereducation/pages/universitieslist.aspx. Accessed 11 Dec 2020

Mousa W, Ghulam Y (2019) Exploring efficiency differentials between Saudi higher education institutions. Manag Decision Econ 40:180–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2995

Ogbonna E (1993) Managing organisational culture: fantasy or reality. Hum Resour Manag J 3:42–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.1992.tb00309.x

Ogbonna E (2019) The uneasy alliance of organisational culture and equal opportunities for ethnic minority groups: a British example. Hum Resour Manag J 29:309–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12227

Ogbonna E, Harris L (2015) Subcultural tensions in managing organisational culture: a study of an English premier league football organisation. Hum Resour Manag J 25:217–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12059

Peters T, Waterman R (1982) In search of excellence. Random House, New York

Saudi General Authority for Statistics (2020) The General Authority for Statistics issues a special report about Saudi women on the occasion of International Women’s Day 2020. https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/news/384 Accessed 21 May 2020

Saudi Unified National Platform (2021) Women empowerment. https://www.my.gov.sa/wps/portal/snp/careaboutyou/womenempowering/!ut/p/z0/04_Sj9CPykssy0xPLMnMz0vMAfIjo8zijQx93d0NDYz8LYIMLA0CQ4xCTZwN_Ay8TIz0g1Pz9AuyHRUBwQYLNQ!!/ Accessed 21 May 2021

Schein EH (1996) Culture: the missing link in organisation studies. Adm Sci Q 41:229–240. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393715

Schein EH (2010) Organisational culture and leadership, 4th edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Smircich L (1983) Concepts of culture and organisational analysis. Adm Sci Q 28:339–359. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392246

Strauss A, Corbin J (1998) Basics of Qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Subbarayalu AV, Prabaharan S, Devalapalli M (2021) Work–life balance outlook in Saudi Arabia. In: Adisa TA, Gbadamosi G (eds) Work–life interface. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, pp. 215–254

Sutic I, Jurcevic M (2012) Strategic management process and enhancement of quality in higher education. Bus Excell 6:147–161. https://hrcak.srce.hr/84686

Tight M (2020) Student retention and engagement in higher education. J Furth High Educ 44:689–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1576860

Van Maanen J (1991) The Smile Factory: work at disneyland. In: Foster P, Moore L, Louis M, Lundberg C, Martin J (eds) Reframing organisational culture. Sage, Newbury Park, CA, pp. 58–76.

Venuleo C, Mossi P, Salvatore S (2016) Educational subculture and dropping out in higher education: a longitudinal case study. Stud High Educ 41:321–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.927847

Willmott H (1993) Strength is ignorance; slavery is freedom: managing culture in modern organisations. J Manag Stud 30:515–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1993.tb00315.x

Yorke M (2000) Developing a quality culture in higher education. Tert Educ Manag 6:19–36. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009689306110

Acknowledgements

This study would not have been possible without the participants, especially those who devoted their time and efforts for academia. Their enthusiasm and spirit for improving academic quality added to the author work and personal experience.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the College of Economy and Administrative Sciences Research Ethics Committee. It was confirmed that the research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. All participants were informed about the purpose and aims of the study, their participation is entirely voluntary and the ways the data would be used.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aldhobaib, M.A. Do subcultures play a role in facilitating academic quality?—A case study of a Saudi higher education institution. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 227 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01250-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01250-0