Abstract

Indigenous groups in the American South relied on local resources including adapted neo-tropical and regionally domesticated crops and native fauna. Arrival of missionaries and non-native animal species (chickens, pigs, and cattle) led to changing subsistence strategies and settlement patterns. The mission communities needed to be self-sustaining and generate surpluses to supply the capital of La Florida (St. Augustine). Zooarchaeological data from sites in La Florida show how mission communities adopted these animals into their subsistence systems. Data shows adoption of domesticates varied across the provinces, and some food items became profitable market commodities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, Indigenous groups in what would become La Florida, subsisted upon the native terrestrial and aquatic fauna abundant in the surrounding forests and fields, lakes, rivers, estuaries, and marine waters of the coast. In some areas, maize agriculture was an established part of the subsistence economy. The arrival of Catholic missionaries from Spain and the introduction of non-native plants and animals into Indigenous territories resulted in a notable change in the subsistence strategies and settlement patterns of local communities. The colonizing Spaniards were required by the Crown to create self-sustaining communities that could also serve as food production areas for St. Augustine – the administrative and political capital of La Florida. This paper focuses on the zooarchaeological data available for three imported domesticated animals—cattle (Bos taurus), pigs (Sus scrofa), and chickens (Gallus gallus)—to discuss the extent to which mission communities in Spanish Florida (ca. 1622–1704) adopted these animals into their subsistence systems. I compare the abundance of domesticated animal remains in faunal assemblages between mission sites in the Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee provinces in temporal older (Guale missions were the first to be established, followed by the missions in Timucua Province, and those in Apalachee Province last). I then compare the relative abundance of domesticated animals recovered and identified from the urban site of St. Augustine (the capital of La Florida) and its western counterpart, San Luis de Talimali. The zooarchaeological record shows that the adoption of European derived domestic animals had varying success across the provinces and that some food items became profitable market commodities in Apalachee Province.

Catholic Missions in Spanish Florida

La Florida was the large swath of southeastern North America claimed by the Spanish as a territory in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This area included present-day Florida and parts of Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana (Fig. 1). The Catholic Mission communities included in this study are located in the Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee provinces of La Florida.

Location of La Florida and Mission Provinces discussed in the text (modified from Worth 2017)

Pedro Menéndez de Aviles established St. Augustine on September 8, 1565, bringing with him the first Catholic (in this case, Jesuit) missionaries (Cushner 2006). In 1566, Menéndez established the town of Santa Elena (modern day Parris Island, South Carolina), in Guale Province. Santa Elena served as the capital of La Florida until 1577. By 1568, letters written by the missionaries to their superiors in Rome reported that the Indigenous people were not easily converted to Christianity, and the priests, often in poor health, were sent to act as chaplains at forts along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts (Cushner 2006). St. Augustine served as a military post at this time. In 1571, the missionaries living in Guale Province along the Georgia coast were withdrawn at the order of Father Juan Bautista de Segura, the Jesuit Vice Provincial in Havana, Cuba (Lowery 1905). Ultimately, the Jesuit missionaries’ efforts were not successful in converting the Indigenous people to Christianity.

The first Franciscan friars arrived in St. Augustine after 1577 and established a mission doctrina at Nombre de Dios in 1587 (Deagan 2002). The series of Franciscan missions in Spanish Florida are referred to as a chain of missions because they stretched from the east to west and north along the coast. The mission settlements were located along well-established Indian routes, which eventually became the Camino Real. Dubcovsky (2016:15–16) notes that, although the “conquistadores imagined themselves exploring uncharted lands, they were actually traveling on Indian-made trails that conditioned where the Europeans could journey and who they met.”

The Franciscan mission chain began in the St. Augustine area, then moved north along the coast in the late sixteenth century. The earliest missions were established among the Saltwater Timucuas, Mocamas, and Guales in what today is northeast Florida and coastal southeastern Georgia. In the early seventeenth century, they moved into interior north Florida among the Freshwater Timucuas, Acueras, Utinas, Potanos, and Yustagas. Finally, in 1633, they moved into northwest Florida among the Apalachees. Beyond Apalachee Province, they were unsuccessful in attracting any of the Indigenous groups into permanent mission settlements. It was not until after the Apalachee Revolt of 1647 and the Timucua Rebellion of 1656 that Spanish government officials sought a complete reorganization of the mission system to be more linear along an east–west axis (the Camino Real) and connect more directly with St. Augustine and northern Mexico (Dubcovsky 2016:18).

Animal Use at Mission Period Sites in Guale Province

The zooarchaeological data analyzed for this paper are compiled from multiple sources, including publications, theses, and technical reports, from nearly 40 years of archaeological investigations at mission sites in La Florida (Blackmore 2000; Newsom and Quitmyer 1992; Reitz 1993; Reitz and Freer 1990; Reitz et al. 2010; Weinand and Reitz 1992). As the excavations that yielded the assemblages from these sites occurred over a span of several decades, and preservation environments were not equal, recovery methods varied. However, the recovery methods used during the original excavations were chosen to optimize the recovery of subsistence data when and where present. Datasets were identified and analyzed by zooarchaeologists trained by Dr. Elizabeth Wing at the Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Elizabeth Reitz (University of Georgia) and her students under her direct supervision analyzed the remains from the sites in Guale and Apalachee provinces, and St. Augustine. Analysis of faunal remains recovered in Timucua Province was completed by zooarchaeologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History – Cynthia Heath in 1976, Arlene Fradkin in 1978, and L. Jill Loucks in 1979 (Emery et al. 2018; Loucks 1979). Thus, identifications and data collection and estimation were completed in as uniform a manner as could be expected over four decades.

Coastal Georgia and South Carolina were home to the Guale Indians, first encountered by the Spanish in the 1560 s (see Fig. 1). Santa Elena was the sixteenth-century capital of La Florida from 1566 until the community relocated to St. Augustine in 1587. Archaeological investigations spanning more than 30 years have identified two forts (San Felipe and San Marcos), the oldest European-style kiln in North America, the town, roads, a plaza, and residential areas (Thompson et al. 2016). Faunal remains were recovered from some of these areas and are discussed below (Table 1; Fig. 2).

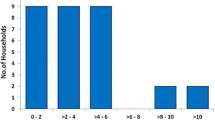

Mission Santa Catalina de Guale was established in the early 1590s on St. Catherines Island. It lasted as a community of Guale and Spaniards, mainly Catholic priests, until 1680, when it was abandoned in the face of English encroachment. Archaeological investigations of the site uncovered two mission churches, one with a cemetery beneath the floor, a convento, cocina, plaza, and Guale village (Reitz et al. 2010; Thomas 1987, 2011). The faunal remains identified from Santa Catalina de Guale record the fewest incidences of domesticated animals of the Guale sites (Fig. 3). Here two pigs are identified, with cattle and chickens absent from the faunal assemblage. This may be because the areas excavated were primarily in the religious complex and not domestic residences.

At the Guale Village (Fallen Tree site), few domesticated animals were identified (Reitz et al. 2010). One pig and one chicken were estimated for the faunal assemblage. Cattle are noticeably absent from the faunal assemblage. At the mission site of Santa Elena, a total of MNI of 52 is estimated for all domesticated animals. Chickens (MNI = 38) are the most abundant, followed by pigs (MNI = 13), and cattle (MNI = 1) (see Fig. 3).

The faunal assemblages from these three sites show a greater reliance on pigs and chickens for meat. Cattle, if present, may have been more important for the secondary resources they provide in the form of milk, dung (fertilizer), and labor. However, it is highly likely that cattle were not kept in abundance along the Georgia coast. Bushnell (1978: 409) notes that the governors of Florida prior to 1600 paid to import cattle from Cuba to the Sea Islands along the Georgia and South Carolina coasts. This plan ultimately failed because the sea islands were inhospitable to cattle raising due to lack of grazing pasture, fresh water, and an abundance of mosquitoes (Bushnell 1978: 409). Reitz and colleagues (2010) note that the hunting of wild animals increased during the Mission period from the preceding pre-Mission periods and centered on deer hunting. Overall, the faunal remains are indicative of the Guales’ efforts to feed themselves, their families, and the resident Spaniards. These assemblages do not suggest European domesticated animals were being raised on a large enough scale to be important market commodities in coastal Georgia as compared to assemblages from mission sites in Apalachee Province in the seventeenth century.

Animal Use at Mission Period Sites in Timucua Province

The Timucua Province is located in north-central Florida, stretching from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the western boundary that is the Aucilla River (see Fig. 2). Excavations at three sites in this province yielded faunal remains and are included here. The Fountain of Youth (FOY) site is located in eastern Timucua Province, at the mouth of the Matanzas River, approximately 1.5 km north of the sixteenth-century town of St. Augustine (Deagan 2002). FOY is the earliest site in Timucua Province. Reitz (1985) analyzed the faunal assemblage from excavations of midden areas. No domestic animals were identified at this site (see Fig. 3). Reitz determined that the people living here consumed only native animal resources. This is very likely due to the early age of the site (early period of contact) and the environmental setting (Reitz 1985). The Matanzas River is a brackish water river—meaning that it is a mix of fresh and saline waters. The Matanzas separates the mainland from the barrier island (known today as Anastasia Island). This area is not productive for animals that need to graze on open grasslands.

The Baptizing Spring site is located in Western Timucua Province. Excavations in separate areas occupied by the Spanish residents and the Timucuan community yielded a fragmentary and poorly preserved faunal assemblage (Loucks 1979). Analysis of the remains was completed by zooarchaeologists at the Florida Museum of Natural History – Cynthia Heath in 1976, Arlene Fradkin in 1978, and L. Jill Loucks in 1979 (Emery et al. 2018; Loucks 1979). There were no chickens identified in this assemblage. Pig and cattle were identified from both residential areas. The Spanish area yielded one pig and one cow based on Minimum Number of Individuals (see Fig. 3). The Timucua area yielded two pigs and one cow (MNI) (Reitz 1992). The limited access to domestic livestock was offset by a reliance on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) (Reitz 1992).

The Fig Springs site, also located in Western Timucua Province, is likely the mission site of San Martin de Ayaocuto. The faunal assemblage was recovered from excavations of domestic features within a structure (Newsom and Quitmyer 1992). Neither cattle nor chickens were identified in this sample. One pig was positively identified (see Fig. 3). Similar to Baptizing Springs, deer were important in the diet, as were fish (Newsom and Quitmyer 1992).

Animal Use at Mission Period Sites in Apalachee Province

In Apalachee Province, five mission sites yielded faunal assemblages of varying sizes (see Fig. 1). The primary limiting factors in the sizes of the faunal assemblages from this province are: a general lack of bone preservation, the goals of the original excavators (mainly centered in non-domestic areas), and sampling methods. Of the five sites included here, three have been extensively excavated (San Luis, Patale, O’Connell), resulting in sizable faunal assemblages (see Table 1, Fig. 2). The other two sites (Ocuya and Ocone) have had more limited excavations and thus smaller faunal assemblages (see Table 1, Fig. 2).

San Luis de Talimali was established at or near Anhaica, a paramount Apalachee town, in 1633 as the first mission community in Apalachee Province. In 1656, it was moved to its current location approximately 8 km to the west and became the western capital of La Florida until its abandonment and destruction in 1704 (Sheppard 2021). The residents of San Luis included one or more Franciscan friars, Apalachee elites, commoners and their families, Apalachee warriors, the Spanish lieutenant governor and his family, Spanish soldiers, and visiting dignitaries. At its height, over 1,400 people were living in and around Mission San Luis.

The community consisted of public spaces, village areas, a Catholic religious complex (including the church, convento, and cocina), the Apalachee council house, and eventually the military area on the northern part of the site that consisted of the fort complex (Lee 2021). Of the total assemblage analyzed to date, European domestic animals, including pigs (MNI = 20), cattle (MNI = 14), and chickens (MNI = 3) composed approximately 43% of the MNI (see Fig. 3; Reitz 1993: table 14.1). Reitz estimates that while cattle are second in terms of MNI, they represent the greatest percentage of the domestic livestock biomass (122 kg), followed by pigs (25 kg), and chickens (0.11 kg).

San Pedro y San Pablo de Patale was occupied from 1633 to 1647 (Marrinan et al. 2000:237). Both cattle and pig are present in the faunal assemblage, as is general bird (Aves). The faunal sample was recovered from the plowzone, thus it is not clear if they are from the more modern/historic period or associated with the mission occupation.

Mission O’Connell was established late in the Spanish Mission period (1690—1704) based on glass trade beads recovered from the site (de Grummond 1997; Marrinan 2021; Wallace 2006). Blackmore (2000) analyzed a sizeable (n = 18,414, 1.15 kg) faunal assemblage from a single trash pit feature (Feature 84) and found that the assemblage was diverse and made up of entirely indigenous fauna. Thus, no domestic animals have been identified from the O’Connell site to date. This is surprising given the late date of the site occupation in the Mission period. It may be that domestic animals were present, but given the taphonomic processes at the site, they are not recovered or if recovered, not identifiable. For example, approximately 66% of the faunal remains from Feature 84 at the O’Connell site were burned and highly fragmented, resulting in few identifiable long bone elements (Blackmore 2000:62). These fragments may be the byproduct of intensive processing of mammal long bones for marrow and grease (Peres 2018a, 2018b).

At the site of San Joseph de Ocuya, a small faunal assemblage was recovered, but the preservation of the remains is poor (Jones 1973:45). Given the limitations of the sample, Reitz (1993) recorded taxonomic identifications and presence/absence. She identified the presence of both pig and cow at this site (see Table 1).

A small faunal sample was recovered from the site of San Francisco de Ocone (Boyd et al. 1951:175). Again, due to poor preservation, the faunal sample is small and limited in data potential. Reitz (1993) recorded presence/absence data. She identified the presence of pig, cattle, deer, and oyster (Crassostrea virginica) (see Table 1).

Comparison of Domesticated Livestock Use across La Florida

In this section I present a comparison of the use of domesticated livestock at colonial period sites in the three main provinces of La Florida. The Guale Province was the first to be colonized, followed by the Timucua Province, and later Apalachee Province. The unique environment of the Guale Province – coastal and Sea Islands – and the turmoil that existed within the earliest mission forays into Indigenous lands are evident in the uneven success of introduced European domesticated livestock. In contrast, the Spaniards learned from these experiences and used them to introduce and raise livestock in Timucua and Apalachee provinces more successfully.

The second part of this section provides a comparison of domesticated livestock use in St. Augustine and San Luis. Both communities were political, religious, economic, and social centers of La Florida in the mid to late seventeenth century. St. Augustine was the eastern capital that housed the major administrative offices of the Spanish government in La Florida. A central feature of the town was the Castillo de San Marcos, a coquina fortification structure built to defend the port city and the Atlantic trade route. Residents of the city included all social, economic, ethnic, and racial classes of Spanish Colonial society. San Luis was the western capital of La Florida, on the western frontier of the colony. It was home to Apalachee chiefs and their families as well as the Spanish Lieutenant Governor and his family, a resident friar (sometimes more than one), Spanish soldiers and their families (Hann 1988; McEwan 1993). The use of domesticated livestock and native fauna at these two communities is part of the story of community subsistence, survival, and economic production.

Guale, Timucua, and Apalachee Provinces

In this section I address the absence/presence and quantities of domesticated animals at Spanish Mission period sites in the three provinces of La Florida. I then compare these data across time and space and discuss the implications of the faunal record for our understanding of local subsistence economies and the larger food production economy of La Florida.

Generally, when domesticated animals are present at these sites, pigs most often make up the greatest quantity (in terms of MNI), and in some cases are the only domesticated taxon present (Table 2; see Fig. 3). However, in Guale Province, the faunal assemblage identified from Santa Elena contains 13 pigs and 38 chickens, nearly three times as many pigs as chickens. Remains of one cow were identified. At the Guale village site of Fallen Tree, one pig, one chicken, and no cattle were identified. At Mission Santa Catalina only the remains of two pigs were identified.

One cow and no chickens have been identified from sites located in the western portion of Timucua Province. This likely is indicative of environmental conditions that were better suited for raising these animals in the western, rather than, the eastern portion of Timucua Province. Poor preservation of osseous remains, especially those from young individuals or more gracile elements/taxa, at sites located in the coastal and estuarine environments of the Fountain of Youth site in the eastern part of Timucua Province may also be a factor (Reitz and Scarry 1985; Reitz and Wing 2008).

In Apalachee Province to the west, the landscape gives way to rolling hills, and when cleared of trees, offers abundant good grazing pastures. The number of domesticated animals identified from sites across the province is greater than that seen in the Guale and Timucua provinces. However, the majority of the domesticated taxa (in terms of MNI and biomass) are from one site – San Luis de Talimali. Cattle remains dominate the San Luis faunal assemblage.

This could be for several reasons—excavations at San Luis include many features associated with domestic life, whereas at other mission sites in the area, the excavations focused on identifying the major structures (like the church) (Shapiro 1987). It is reasonable to expect architectural features at these sites, such as post molds and roof drip lines of religious structures, to yield few animal remains. The soils in Apalachee Province are acidic (pH range of 3.5–6) and not well suited to the preservation of archaeofaunal remains (Bierce-Gedris 1981:231; USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service 2022). The most abundant assemblages are recovered from trash pits and other closed contexts, are carbonized, and recovered using water screening with window mesh (1.6 mm). Those types of features have not been identified or excavated at all of the mission sites in the area, nor were all of the assemblages recovered with methods best suited for the recovery of subsistence data.

San Luis and St. Augustine

St. Augustine, a military and port town on the Atlantic Coast founded in 1565, was the administrative and political capital of La Florida from 1587–1763. In 1702, St. Augustine boasted a population of approximately 1,500 residents, including administrative/political leaders, civilians, soldiers, refugees, and religious leaders (Bushnell 1994). St. Augustine was located in eastern Timucua Province among a dynamic coastal, estuarine, and riverine environment. The native flora consists of palm scrub on sandy soils. The largest terrestrial fauna native to this area are white-tailed deer and turkey. The coastal waters provide access to a variety of aquatic resources. It is not surprising that the faunal assemblages from St. Augustine show a greater use of indigenous foods, especially fish. Reitz (1985) notes that the use of fish by the Spanish differed from that of the Indigenous residents. The Spanish fished for bigger individuals and often in deeper waters as compared to the use of smaller estuarine fish by the Timucua (Reitz 1985). There are fewer remains of domesticated animals in the samples (Fig. 4).

Five soldiers were deployed from St. Augustine to San Luis in 1638 to protect Spain’s territory along the western frontier of La Florida (McEwan 1993:296). A dedicated fort was established at San Luis in the 1650s, and the garrison grew to 45 soldiers in the 1680s (Bushnell 1978; Hann 1988). The community of San Luis de Talimali was established at its current location as the western capital of La Florida in 1656. The cacique (chief) of Anhaica, the western capital of Apalachee, moved his village to be closer to the Catholic church founded at this location (Bushnell 1994; Sheppard 2021). An increasing number of Spanish ranches and farms proved the agricultural viability of the region. The military presence offered security while the agricultural opportunities seemed limitless. The Spanish government granted land across the northern part of Florida to “influential Spaniards.” These factors ultimately led to an influx of Spanish colonists (peninsulares and criollos) into Apalachee Province seeking to raise their social and economic status (Arnade 1961; Bushnell 1978).

The San Luis community demographics included Apalachee and Spanish men, women, and children. They represent a cross-section of seventeenth-century society in La Florida. At its height, the population of San Luis was 1,500 people, including Indigenous and Spanish civilians, religious leaders, and military leaders and troops. San Luis retained its social, cultural, political, military, and religious importance until its abandonment in 1704, in advance of the invading British and allied forces (Sheppard 2021).

From the faunal samples recovered from San Luis and analyzed by Reitz (1993; Weinand and Reitz 1992), we know the following about domestic animal consumption. An MNI of 20 pigs with a total biomass of 25 kg pork, 14 cattle with a total biomass of 122 kg of beef, and three chickens yielding a total biomass of 0.11 kg are known from this site (see Fig. 4). Overall, the biomass estimates suggest that the residents of San Luis were eating more beef than any other type of meat, and eating more of it than the residents of St. Augustine.

Food Production Economies in La Florida

The Spanish Crown supplied the start-up resources and capital for the missions from the Patronado Real de las Indias, or king’s purse (Bushnell 1994). It was never the intent of the Spanish crown to supply the La Florida communities fully or indefinitely with the food and objects necessary for daily and spiritual life. The mission communities were expected to become self-sustaining and produce a surplus of food and goods to send back to St. Augustine and other ports in the Spanish Atlantic Empire.

Here I explore the archaeological and documentary evidence for food production economies in La Florida and specifically Apalachee Province. I use multiple lines of evidence, including the previously discussed zooarchaeological data, historical documents, and artifactual and contextual data to draw conclusions about the type and extent of food production that took place in La Florida. I specifically examine the evidence for animal husbandry of cows, pigs, chickens and the secondary sources these animals provide.

Cattle Ranching

During the seventeenth century, Spanish elites established cattle ranches in western Timucua and Apalachee provinces (Hann 1988:136). As noted by Bushnell (1978: 408), the growth of the cattle ranches was enabled by many Indigenous peoples dying due to epidemics, causing large swaths of agricultural fields to lay abandoned. These lands were given to high-ranking families in the Spanish government to encourage a self-sustaining colony, and one that could supply other Spanish interests with beef, tallow, and hides.

Western Timucua Province is likely the site of the earliest cattle ranch, though specific locational and temporal information have yet to be identified (Bushnell 1978). The Hacienda de la Chua, while not the first cattle ranch, is the most famous. Hacienda de la Chua was one of several ranches owned by Menendez Marquez and his family (Bushnell 1978) The modern city of Alachua in Alachua County, Florida is named for this hacienda. Starting a cattle ranch was not a cheap endeavor. Bushnell (1978:418) estimates the start-up costs to have been over 6,000 pesos, at least four years’ worth of salary for government officials in La Florida.

According to tax rolls from 1698 and 1699, there were nine Spanish ranches located in Apalachee Province (Arnade 1961:1220). Ranchers were required to pay taxes to the Spanish Governor, and in the late 1600s the rate was assessed at 10%, paid in heads of cattle (1 cow per 10 head of cattle) (Arnade 1961:122). During these two documented tax years, 60 head of cattle were paid to the governor, who maintained an official slaughterhouse in St. Augustine. The largest ranch paid 15 head (Arnade 1961:122). Based on these data points we can estimate that a minimum of 600 cattle were in La Florida. Given the highest tax assessment of 15 head of cattle, which translates to a herd of 1,500 individual animals, it is safe to assume that more than 1,500 cattle roamed La Florida in the seventeenth century.

For the most part cattle herds were free ranging, as documented in the complaints of the Apalachee that cattle were trampling their agricultural fields and other complaints by friars that Natives would kill off the cattle to drive the Spanish from their lands (Bushnell 1978; Hann 1988). Nevertheless, the Spanish were determined to establish successful economic ventures in La Florida. Cattle ranching would be the most successful of those ventures.

Locally, cattle were important as a food resources. Beef was eaten fresh or as salt beef. Organs were incorporated into traditional recipes. Residents of San Luis ate more beef than any other animal meat and consumed more beef than their counterparts in St. Augustine (Reitz 1993). The secondary resources derived from cows, namely milk and the derivative dairy products (butter, cheese), tallow, and hides, were also important parts of the provincial economy. The first deputy governor established a cattle ranch not far from San Luis. The historical documents mention that this deputy governor required Apalachee men, under the repartimiento (labor requirement), to work for the cattle ranch (Hann 1988). There is also mention in the historical documents that the village of Ocuya owned community cattle and that an individual at Patale personally owned cattle. Residents of Patale complained that cattle from Marcos Delgado’s cattle ranch, Our Lady of the Rosary, damaged their crops. In the early 1650s, Manuel, the Chief of Asile (another Apalachee Mission) “objected to Governor Ruiz de Salazar y Vallecilla’s cattle operation on the coastal lowlands below Asile and Ivitachuco because it threatened foodstuffs obtained from that area, such as acorns and palm berries” (Hann 1988:135).

In 1693, 60 years after the first mission was established in Apalachee Province, Governor Laureano de Torres y Ayala purchased more than two tons of salt beef, three steers, and three calves locally in Apalachee province (Hann 1988:135). These provisions were to be eaten by members of his overland expedition from San Luis to Pensacola Bay. He also purchased 22 locally produced cheeses for the trip, all supplied by Spanish rancher Marcos Delgado (Hann 1988:135).

Certainly, every part of the cow was used once slaughtered. While the meat was eaten fresh or salted for storage and shipment, the hides were tanned for leather and used locally or sold at market (Bushnell 1978). The marrow and grease bound up in the skeletons of cattle were processed into tallow and exported as important non-food commodities (Bushnell 1994: 139). Marrow and grease extraction have recognizable signatures in the archaeological record (Peres 2018a, 2018b). A large quantity of fragmented and burned bone from Feature 84 at O’Connell suggests this type of intensive grease extraction. According to the historical documents, “hides and tallow” were “the principal export products of Apalachee’s cattle industry” often being shipped to Havana (Cuba) (Hann 1988:137). In 1675, the province sent 150 hides and 3,800 lb (1,724 kg) of tallow to Havana (Hann 1988:137), probably by way of boats belonging to the Havana merchants and sent to the mouth of the Suwannee River for the goods (Bushnell 1978:424).

Dairying

In Spain, milk from goats and cows was important to the cuisine. Goats’ milk was used to make cheese (which was easier stored than milk) (Campbell 2017:32). However, in La Florida, goats were not easily assimilated and raised. Cows were better suited to the harsh subtropical environments, and became the preferred dairy animal. The importance of cow’s milk and milk products to Spanish cuisine is evident in historical records and in Spanish recipes recorded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Unfortunately, the faunal assemblages from these sites have little to say on the use of milk cows. Weinand and Reitz (1992) addressed the issue of dairying in Apalachee Province with the data from San Luis. They assert that “many of these animals were slaughtered young, indicating that they were raised specifically for food rather than dairy production or traction” (Weinand and Reitz 1992:3–4). However, it is likely that our conclusions about the absence of dairying evidence are biased by taphonomy (and lack of preservation) and that the previous excavations focused on identifying and documenting public spaces, sacred spaces, and overall site layout.

The historic documents do record the occurrence of milk at San Luis and its importance to at least the ruling class Spanish families. Juana Caterina de Florencia (granddaughter of the first Lieutenant Governor of Apalachee Province), married Captain Jacinto Roque Perez who was appointed as Deputy Governor of Apalachee in 1700, and raised her ten children at San Luis. She used her status and authority to demand “she be given an Indian to go and come every day with a pitcher for the house of said deputy” (Boyd et al. 1951:25; emphasis added).

The importance of the pitcher form is evidenced by Señora Juana specifying that milk be brought in a pitcher. The ceramic assemblage at San Luis has yielded a number of colonoware vessels in the form of pitchers (Bruin 2019; Lee 2021; Vernon 1988). That these vessels are colonoware speaks to the form’s importance to daily life at San Luis. Apalachee Colonoware ceramics were made by Indigenous potters using locally sourced materials (Cordell 2002). These are unique in that they were created in Spanish forms to fill the void left by a lack of Spanish majolica imports to the colony. According to a comparison of colonial-period sites in the Southeast that yielded Indigenous-made colonowares, it is notable that pitchers are only present in the samples from Apalachee and West Florida sites (Cobb and DePratter 2012: table 1). There may have been a greater need for milk pitchers in Apalachee Province due to the success of cattle ranching in this area and the large Spanish population at San Luis, especially after 1670. Notably, the majority of pitcher forms identified at San Luis are from Feature 174 (minimum number of vessels = 10) (Lee 2021: table 6.3, fig. 6.3e). This feature is a trash pit associated with Structure 4, an excavated whitewashed wattle and daub structure less than 5 m from the presumed route of the Camino Real (Lee 2021: figs. 6.1 and 6.2). There are several possible interpretations for Structure 4, one of which is that it was the home of the deputy governor and his family (Lee 2021; Shepard 2009).

Pig Husbandry

Pigs were introduced early into Spanish Florida and raised across the colony by Indigenous and Spanish members of mission communities. Pigs have been identified archaeologically from 82% (n = 9) of the sites in the sample. They were likely raised at the other mission sites, but are not well preserved in the deposits. Pigs were useful for meat and fat (especially lard). Hann (1988:132) suggests that lard (and butter) replaced nut oil, which was more labor intensive to extract. Historical documents record lard as an important locally consumed item and one of Apalachee’s export commodities (Hann 1988:132). Pig raising as an economy was lucrative for Apalachees until the late seventeenth century, when the Spaniards expanded into the market. A combination of price control and new Spaniards moving into the area and raising their own hogs led to many Apalachees abandoning the practice (not necessarily willingly) (Hann 1988:136–137).

Chicken Husbandry

Chickens were among the first, and most successful, of the domestic animals brought to La Florida by the Spanish. Chicken was considered a special food with curative properties (Bushnell 1994:57). The first Franciscan friar to arrive on the Georgia Sea Islands in 1587, Father Baltasar Lopez, was taken ill in 1601 (Bushnell 1994: 57). Two physicians in St. Augustine advised Governor Mendez Cano that Father Baltasar Lopez’s health would only improve if he ate chicken (Bushnell 1994:57). This resulted in an increase in the friar’s daily ration of 3 reales to 9 or 10, necessitated by the high cost of chicken (8–10 reales) (Bushnell 1994:57).

Catholic religious doctrine and cookbooks from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries highlight the importance of eggs and chicken broth as components of dishes prepared for and eaten on abstinence days (Hayward 2017; Worth 2007). Raimondo Gómez, a Franciscan (lay) friar and cook, published a collection of recipes under the pen name, Juan Altamiras. Altamiras’s New Art of Cookery (1758) includes recipes for roasting a capon, making sauces with egg yolks, and adding hard boiled eggs to soups (Hayward 2017; Worth 2007). Campbell (2017) notes the importance of chickens to the quotidian diet of people of all socioeconomic classes in Spain during the Early Modern period. The importance of chicken (and other animal meats) to the Spanish diet necessitated that European domestic animals be imported into the Americas to meet the needs of the peninsulares, criollos, and mestizos in La Florida.

Archaeologically, we can recover the bones and eggshells of chickens in La Florida, though their preservation is dependent on context, local soil conditions, site areas investigated, and recovery methods. Chicken bones are present at two sites in Guale Province, with the greatest abundance of any site identified at Santa Elena (Reitz 1993).

Chickens were introduced into Apalachee Province and became another commodity to be exported out of the port at St. Marks (Bushnell 1994:116; Hann 1988:137). In 1685, 100 chickens were part of the cargo loaded onto a ship at St. Marks to be traded elsewhere (Hann 1988:137). Chicken bones are identified from multiple contexts at San Luis (Weinand and Reitz 1992). Eggshells were recovered from the O’Connell site, though their taxonomic identification is uncertain at this time (R. Marrinan, pers. comm. 2019).

Another proxy for the presence of chickens at a site is the identification of gastroliths (Taber et al. 2019). Gastroliths are small hard objects ingested by birds to help break down their food. During the digestion process, they become smoothed with some possible pitting and they have a matte appearance (Lucas and Hunt 2022). At San Luis, there are two areas that have strong evidence for chicken raising. One is a small structure interpreted as a henhouse in the yard of a Spanish house (Structure 4) in the Spanish Village area. The second is in the kitchen adjacent to the convento. Here more than 100 presumed gastroliths have been identified (Lee 2021). The majority of these presumed gastroliths are smoothed-edged pieces of glass, quartz, porcelain, and chert with a matte finish (Lee 2021). Further analysis is needed to unequivocally identify them as gastroliths (see Lucas and Hunt 2022).

Information from historical documents, both personal letters and journals and official government records, outline the importance of domesticated animals to Spanish colonial cuisine and economy in La Florida. The archaeological record yields the physical data to quantify the temporal and geographical importance of these animals across La Florida. Combining these with the secular, religious, and medical beliefs about specific animals to Spanish cuisine, and especially for those that strictly observed Catholic liturgical rules and calendars, paints a picture of a complex, nuanced, and flavorful foodways in La Florida.

Discussion and Conclusions

The Spanish colonized La Florida in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. To keep their foothold in the area, they had to create self-sustaining communities. St. Augustine was located in an environment better suited to fishing and oystering than to terrestrial food production. The traditional Spanish foodways that relied on the production of cattle, pigs, and chicken could not be sustained in this area at levels that allowed for a surplus of foodstuffs to feed the growing urban community. Initially, residents of the capital depended in large part on the Guales and other Indigenous groups along the Atlantic coast for food, trade, and labor. However, depopulation of those areas due to disease, slave-raiding, and death, meant the Spanish had to find other sources for their agricultural enterprises. The Spanish government turned their eyes west to the fertile lands of Apalachee Province. Here the Apalachees’ traditional and transformed farming, hunting, and fishing economies produced a surplus of foodstuffs to feed the resident and visiting friars, government officials, and soldiers. Basket loads of maize, beef, and venison were carried on the backs of Apalachee men overland to St. Augustine, or via boat around the southern tip of the Florida Peninsula, stopping in Havana before sailing on to St. Augustine (Bushnell 1994; Hann 1988). These food items became market commodities, bringing in profits for the friars, government officials, and the Apalachee chiefs (Bushnell 1994).

A synthesis of the historical documents and the archaeological record suggests that the feeding of the friars and families in Apalachee Province during the Spanish Mission period was dominated by Indigenous foods and Indigenous labor (Peres 2021). In this way, Indigenous foodways persisted throughout the period, but were not completely unchanged. The addition of European livestock, namely cattle, pigs, and chicken, and their secondary resources, surely came with a learning curve in terms of animal management, processing, and preparation. Few European staple crops were successfully introduced into Spanish Florida, despite attempts to grow wheat and garbanzo beans (Scarry 1993). European fruits saw higher rates of success. Peaches, watermelons, and figs are known archaeologically from sixteenth-century sites in St. Augustine (Reitz and Scarry 1985). They are identified from the Council House and Spanish domestic contexts at San Luis that date to the seventeenth century (Scarry 1993: table 13.2).

Objectively, it should have been clear to the Spanish colonizers that Indigenous subsistence systems were more than adequate for supporting thriving communities prior to the Spaniards’ arrival. However, the prevailing Spanish beliefs about food at that time were inextricably linked with morality, class, health, and religious doctrine (Campbell 2017; Earle 2012). It is well documented that the Spanish desired to keep their traditional lifeways, including the Catholic Iberian diet, and recreate it in the Spanish colonies (Earle 2012; Hann 1988; Reitz and Scarry 1985). The result was the importation of European domesticated animals and plants, and the incorporation of useful plants and animals from local indigenous environments and/or brought from other parts of the Americas (e.g., chocolate, chili peppers, turkeys, and corn to Europe).

In La Florida, individual friars were giving the task of setting up and/or trying to maintain mission communities that could produce quantity, quality, and the right type of foods to feed the community members, the friar, the chiefs, and produce a surplus to be traded with, sold, or paid as tax to the Spanish administrative ranks. Indigenous community members were expected to grow and raise new foodstuffs (like wheat, cows, chickens, and pigs) to fill these needs. This effort was met with variable success. The destruction of the missions in 1704 ended a system that was in its infancy, relatively speaking (Sheppard 2021). The ultimate success or failure of the imported Iberian agrosystem into La Florida was upended by these external social and political influences. The Seminole Tribe of Florida and the Muscogee (Creek) of Alabama and Georgia continued the cattle ranching tradition in the mid-1700s until the present day. Today, cattle ranchers in Florida trace their stock (known as Florida Cracker Cattle) back to those introduced to the region by the Spanish (Rey 2010).

References

Altamiras, J. (1758). Nuevo Arte de Cocina, Sacado de la Escuela de la Experiencia Economica. Imprenta de Don Juan de Bezáres, dirigida por Ramon Martí, Impresor, Barcelona.

Arnade, C. W. (1961). Cattle ranching in Spanish Florida, 1513-1763. Agricultural History 35(3): 116-124.

Bierce-Gedris, K. (1981). Apalachee Hill: The Archaeological Investigation of an Indian Site of the Spanish Mission Period in Northwest Florida. Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Blackmore, C. (2000). Analysis of Faunal Remains from Feature 84, a Protohistoric Refuse Pit from the O’Connell Mission Site (8LE157). Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Boyd, M. F., Hale, G. S., and Griffin, J. W. (1951). Here They Once Stood. University of Florida Press, Gainesville.

Bruin, A. (2019). A Comparative Study of Colonoware Ceramics from Two Missions Sites in Apalachee Province, Leon County, Florida. Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Bushnell, A. (1978). The Menendez Marquez Cattle Barony at La Chua and the determination of economic expansion in seventeenth-century Florida. Florida Historical Quarterly 56(4): 407-431.

Bushnell, A. (1994). Situado and Sabana: Spain’s Support System for the Presidio and Mission Provinces of Florida. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

Campbell, J. (2017). At the First Table: Food and Social Identity in Early Modern Spain. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Cobb, C. R. and DePratter, C. B. (2012).Multisited research on colonowares and the paradox of globalization. American Anthropologist 114(3): 446-461.

Cordell, A. S. (2002). Continuity and change in Apalachee pottery manufacture. Historical Archaeology 36(1): 36-54.

Cushner, N. P. (2006). Why Have You Come Here? The Jesuits and the First Evangelization of Native America. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Deagan, K. A. (2002). Historical Archaeology at the Fountain of Youth Park (8-SJ-31), St. Augustine, Florida, 1934–2007. https://www.flagler.edu/media/documents/campus-community/historic-st-augustine-research-institute/funded-research/2002-Deagan-FOY-report-reduced.pdf

de Grummond, E. C. (1997). Beads from the O’Connell Site (8LE157): A Study of Bead Chronology and the Seventeenth-Century Spanish Missions of Apalachee Province. Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Dubcovsky, A. (2016). Informed Power, Communication in the Early America South. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Earle, R. (2012). The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race, and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492-1700. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Emery, K. F., Loucks, L. J., Milanich, J. T., Fairbanks, C., Heath, C., Fradkin, A., LeFebvre, M., and Brenskelle, L. (2018). Baptizing Spring Zooarchaeological Data. In Emery, K. F., Guralnick, R., LeFebvre, M., Brenskelle, L., and Wieczorek, J. W. (eds.), ZooArchNet. https://doi.org/10.6078/M7H70CX3

Hann, J. H. (1988). Apalachee: The Land between the Rivers. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Hayward, V. (2017). New Art of Cookery: A Spanish Friar’s Kitchen Notebook by Juan Altamrias. Rowman and Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Jones, B. C. (1973). A semi-subterranean structure at mission San Joseph de Ocuya, Jefferson County, Florida. Division of Archives, History, and Records Management, Florida Department of State, Tallahassee.

Lee, J. (2021). Imported ceramics and colonowares as a reflection of Hispanic lifestyle at San Luis de Talimali. In Peres, T. M. and Marrinan, R. A. (eds.), Unearthing the Missions of Spanish Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, pp. 167-214.

Loucks, L. J. (1979). Political and Economic Interactions between Spaniards and Indians: Ethnohistorical and Archaeological Perspectives of the Mission System in Florida. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Lowery, W. (1905). The Spanish Settlements within the Present Limits of the United States Florida 1562-1574. Knickerbocker Press, New York.

Lucas, S. G. and Hunt, A. P. (2022). Gastroliths in archaeology: a note of caution. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 32(2): 541-543.

Marrinan, R. A. (1993). Archaeological investigations at Mission Patale, 1984-1992. In McEwan, B. G. (ed.), The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 244-294.

Marrinan, R. A. (2021). The lives of friars in Apalachee Province. In Peres, T. M. and Marrinan, R. A. (eds.), Unearthing the Missions of Spanish Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, pp. 244-279.

Marrinan, R. A., Halpern, J. A., Heide, G. M., and Blackmore, C. (2000). An overview of findings from the O’Connell Mission site, Leon County, Florida. Florida Anthropologist 53(2-3): 224-249.

McEwan, B. G. (1993) Hispanic life on the seventeenth-century Florida frontier. In McEwan, B. G. (ed.), The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 295-321.

Newsom, L. and Quitmyer, I. R. (1992). Archaeobotanical and faunal remains. In Weisman, B. R. (ed.), Excavations on the Franciscan Frontier: Archaeology at the Fig Springs Mission. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 206-234.

Orr, K. L. (2001). Vertebrate fauna from Nombre de Dios (8-SJ-34), St. Johns County, Florida. Ms. on file, Zooarchaeology Laboratory, Georgia Museum of Natural History, University of Georgia, Athens.

Orr, K. L. and Colaninno, C. (2008). Native American and Spanish subsistence in sixteenth-century St. Augustine: vertebrate faunal remains from Fountain of Youth (8SJ31), St. Johns Co., Florida. In Deagan, K. (ed.), Historical Archaeology at the Fountain of Youth Park (8-SJ-31 ), St. Augustine, Florida: 1954–2007, Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainesville.

Peres, T. M. (2018a). Splitting the bones: marrow extraction and Mississippian Period foodways. In Peres, T. M. and Deter-Wolf, A. (eds.), Baking, Bourbon, and Black Drink: Foodways Archaeology in the American Southeast. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, pp. 51-62.

Peres, T. M. (2018b). Zooarchaeological approaches to the identification of bone fat production in the archaeological record. Ethnobiology Letters 9(2):107-109.

Peres, T. M. (2021).Feeding families and friars in Apalachee Province during the Mission Period. In Peres, T. M. and Marrinan, R. A. (eds.), Unearthing the Missions of Spanish Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, pp. 215-243.

Reitz, E. J. (1980). Vertebrate remains from Santa Elena, South Carolina, 1979 excavations. Ms. on file, Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia, Athens.

Reitz, E. J. (1985). Faunal evidence for sixteenth-century Spanish subsistence at St. Augustine, Florida. Florida Anthropologist 38(1-2): 54-69.

Reitz, E. J. (1993). Evidence for animal use at the missions of Spanish Florida. In McEwen, B. G. (ed.), The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 376-398.

Reitz, E. J. and Freer, J. (1990). Vertebrate fauna from the Spanish Village at San Luis de Talimali, Feature 6. Manuscript on file, Mission San Luis Archaeology Laboratory, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee, FL.

Reitz, E. J., Pavao-Zuckerman, B., Weinand, D. C., Duncan, G. A., and Thomas, D. H. (2010). Mission and Pueblo Santa Catalina de Guale, St. Catherines Island, Georgia (USA): A Comparative Zooarchaeological Analysis. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Reitz, E. J. and Scarry, C. M. (1985). Reconstructing Historic Subsistence with an Example from Sixteenth-Century Spanish Florida. Society for Historical Archaeology, Germantown, MD.

Reitz, E.J. (1992). The Spanish colonial experience and domestic animals. Historical Archaeology 26(1): 84–91.

Reitz, E. J. and Wing, E. S. (2008). Zooarchaeology, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rey, J. R. (2010). Florida Cracker Cattle. Animal Sciences Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville.

Scarry, C. M. (1993). Plant production and procurement in Apalachee Province. In McEwan, B. G. (ed.), The Spanish Missions of La Florida. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp. 357-375.

Shapiro, G. (ed.) (1987). Archaeology at San Luis: Broad-Scale Testing, 1984–1985. Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, Tallahassee.

Shepard, H. E. Jr. (2009). Architectural Research: The Provincial Governor’s House, Mission San Luis, Tallahassee, Florida. Manuscript on file, Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research, Tallahassee.

Sheppard, J. (2021). “With the many enemies that it has”: the collapse of Apalachee Province. In Peres, T. M. and Marrinan, R. A. (eds.), Unearthing the Missions of Spanish Florida. University of Florida Press, Gainesville, pp. 304-324.

South, S. A. (1980). The Discovery of Santa Elena. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

South, S. A. (1982). Exploring Santa Elena 1981. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

South, S. A. (1983). Revealing Santa Elena 1982. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

South, S. A. (1985). Excavation of the Casa Fuerte and Wells at Ft. San Felipe 1984. South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Taber, E. C., Wilson, D. C., Cromwell, R., Wynia, K. A. and Knowles, A. (2019). Transfer-printed gastroliths: fowl-ingested artifacts and identity at Fort Vancouver’s village. Historical Archaeology 53:86-102.

Thomas, D. H. (1987). The archaeology of Mission Santa Catalina de Guale, part 1: search and discovery. American Museum of Natural History, New York.

Thomas, D. H. (2011). St. Catherines: An Island in Time. 2nd ed. University of Georgia Press, Athens.

Thompson, V. D., DePratter, C. B., and Roberts Thompson, A. D. (2016). A preliminary exploration of Santa Elena's sixteenth-century colonial landscape through shallow geophysics. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 9: 178–190.

USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service. (2022). Leon County, Florida. Web Soil Survey. https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/surveylist/soils/survey/state/?stateId=FL

Vernon, R. (1988). 17th-century Apalachee Colono-Ware as a reflection of demography, economics, and acculturation. Historical Archaeology 22: 76-82.

Wallace, J. T. (2006). Indigenous Ceramics from Feature 118 at the O’Connell Site (8LE157): A Late Spanish Mission in Apalachee Province, Leon County, Florida. Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Weinand, D. C. and Reitz, E. J. (1992). Vertebrate fauna from San Luis de Talimali, 1992. Manuscript on file, Mission San Luis Archaeology Laboratory, Division of Historical Resources, Tallahassee, FL.

Worth, J. (2007). Spanish colonial recipes. Electronic document, https://pages.uwf.edu/jworth/jw_spanfla_recipes.html, accessed July 2019.

Worth, J. (2017). Spanish Florida, 1587–1706. Electronic document, https://pages.uwf.edu/jworth/SpanishFlorida_1587-1706.jpg, accessed April 2021.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Zooarchaeology in the Modern Era Working Group (ICAZ) First Annual Conference. Many thanks to Rebecca Gordon and Eric Tourigny for organizing the conference and this special journal issue, and their patience. I appreciate the helpful comments provided by Suzanne Needs-Howarth and one anonymous reviewer. Unpublished reports and data cited in the text were graciously provided by Elizabeth Reitz, Jerry Lee, and Rochelle Marrinan. Special thanks to my writing partner, Katie Foss, and Any Good Thing (AGT) for the encouragement and discipline.

Land Acknowledgment

I acknowledge that my institution, Florida State University, and the city where I live and conduct research, Tallahassee, is located on land that is the ancestral and traditional territory of the Apalachee Nation, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the Miccosukee Tribe of Florida, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida. The data included in this paper are from research projects conducted on land that are the ancestral and traditional territories of the Apalachee Nation, Mocama, Timucua, Yamassee, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, the Miccosukee Tribe of Florida, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida. I pay my respects to their Elders past and present, and extend that respect to their descendants, to future generations, and to all Indigenous people.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares there are no potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peres, T.M. Subsistence and Food Production Economies in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Florida. Int J Histor Archaeol 27, 274–295 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00667-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-022-00667-2