Abstract

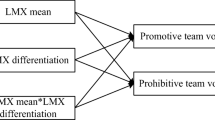

That individuals hold personal, implicit beliefs about the consequences of voice (i.e., implicit voice theories (IVTs)), and thus are inherently reluctant to speak up, is one of the most ubiquitous concepts in the voice literature. An extensive body of research also shows how situational factors (e.g., voice climate) profoundly affect voice. Unfortunately, few studies explore how dispositional beliefs combine with situational factors to influence voicing in teams; thus, the literature is unclear about whether and how leaders can encourage voice when their team members implicitly believe that voice is unsafe and inappropriate (i.e., high IVTs). We address this question by proposing a moderated-mediation model linking leaders’ prior reactions to voice (i.e., voice acceptance versus rejection) to team voice intentions via voice climate, such that encouraging leader behaviors (acceptance), unlike discouraging leader behaviors (rejection), creates positive voice climates that increase team voice intentions. Furthermore, drawing from the trait activation theory, we propose that team IVTs composition (i.e., the average IVTs held by each team member) moderates the mediated effect of voice climate on team voice intentions, such that this relationship is strongest for teams with high IVTs because, for these teams, positive voice climates are both highly salient to, and disconfirming of, implicit voice beliefs. Results of a multi-task team experiment support this model. We discuss the theoretical implications of considering person and situation factors in tandem, the potential influence of team IVTs composition, and practical implications for how leaders can inspire voice in teams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We conceptualize team voice as intentions because our experimental methodology does not permit future assessments of voice. We focus on intentions based on theoretical and meta-analytical evidence that intentions are strongly related to behaviors (e.g., Ajzen, 1991; Webb & Sheeran, 2006) as well as experimental research that has measured behavioral intentions as an indicator of future behavior (e.g., van Kleef et al., 2021), including voice intentions specifically (e.g., King et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2020). We return to this matter in our limitations.

Our perspective is that IVTs can also be conceptualized as a shared construct (e.g., Knoll et al., 2021) that emerges over time via shared experiences, which aligns with Kozlowski and Klein’s (2000) notion that collective constructs can emerge in different ways in different contexts. Much like the emergence of team knowledge structures (Kozlowski & Chao, 2012), we believe it is plausible for team members’ IVTs to converge and become similar over time through repeated interactions and shared experiences. However, given that research and theory on IVTs describes such beliefs as relatively immutable and consistent across contexts, we expect that many teams—particularly those at early stages of formation or that are only together for a finite period of time (which describes teams in the present research)—do not reach a point at which shared experiences regarding voice expectations start to create permanent changes to team members’ IVTs. That is, even if team members come to view voice as safe in their shared context, this does not mean that they would alter their implicit beliefs regarding voice safety across other contexts (Detert & Edmondson, 2011). Moreover, from a methodological perspective, we measured IVTs before our study, at which point there would not have been any grounds to expect convergence because the team members had not yet interacted.

At the conclusion of each experimental session, we debriefed participants on the true nature of the study, including the role of the confederate leader. As this manipulation could have disproportionately affected team ideation results, we explained that we would randomly select four participants for the $50 gift card as opposed to gifting the top teams. At the conclusion of the study, we emailed these four participants a $50 gift card redeemable at the Campus Bookstore.

Given the dispositional nature of IVTs, it is possible that team IVT composition could have also moderated the relationship between leader reactions and voice climate. We conducted a post hoc analysis to test this possibility in which we allowed for team IVT composition to simultaneously moderate both the first and second stages of our mediation model. To do so, we used Model 58 in Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro for SPSS and bootstrapped confidence intervals calculated with 5,000 iterations. The results of this analysis indicated a nonsignificant interaction effect of leader reactions to voice and team IVT composition on voice climate (B = − .74, 95% [− 1.55, .08]) and a significant interaction effect of voice climate and team IVT composition on team voice intentions (B = 1.58, 95% [.13, 3.05]). The results, therefore, suggest that team IVT composition is best modeled strictly as a moderator of the relationship between voice climate and team voice intentions.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior organizational behavior and human decision processes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ashford, S. J., Rothbard, N. P., Piderit, S. K., & Dutton, J. E. (1998). Out on a limb: The role of context and impression management in selling gender-equity issues. Administrative Science Quarterly, 43(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393590

Bacharach, S. B., Bamberger, P., & McKinney, V. (2000). Boundary management tactics and logics of action: The case of peer-support providers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45(4), 704–736. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667017

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice–Hall.

Bashshur, M. R., & Oc, B. (2015). When voice matters: A multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. Journal of Management, 41(5), 1530–1554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314558302

Bateman, T. S., & Crant, J. M. (1993). The proactive component of organizational-behavior—A measure and correlates. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(2), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030140202

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370.

Bell, S. T. (2007). Deep–level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 595–615.

Bledow, R., Carette, B., Kühnel, J., & Bister, D. (2017). Learning from others’ failures: The effectiveness of failure stories for managerial learning. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 16(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2014.0169

Bowers, K. S. (1973). Situationism in psychology: An analysis and a critique. Psychological Review, 80(5), 307–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0035592

Bradley, B. H., Klotz, A. C., Postlethwaite, B. E., & Brown, K. G. (2013). Ready to rumble: How team personality composition and task conflict interact to improve performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029845

Brykman, K. M., & King, D. D. (2021). A resource model of team resilience capacity and learning. Group & Organization Management, 46(4), 737–772. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011211018008

Brykman, K. M., & O’Neill, T. A. (2020). Beyond aggregation: How voice disparity relates to team conflict, satisfaction, and performance. Small Group Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496420956391

Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 851–875.

Chamberlin, M., Newton, D. W., & LePine, J. A. (2018). A meta-analysis of empowerment and voice as transmitters of high-performance managerial practices to job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1296–1313. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2295

Chan, D. (1998). Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.2.234

Chiocchio, F., & Essiembre, H. (2009). Cohesion and performance. Small Group Research, 40(4), 382–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496409335103

Cooper, W. H., & Richardson, A. J. (1986). Unfair comparisons. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.2.179

Crant, J. M., Kim, T.-Y., & Wang, J. (2011). Dispositional antecedents of demonstration and usefulness of voice behavior. Journal of Business and Psychology, 26(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9197-y

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.26279183

Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54(3), 461–488. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.61967925

Detert, J. R., Burris, E. R., Harrison, D. A., & Martin, S. R. (2013). Voice flows to and around leaders: Understanding when units are helped or hurt by employee voice. Administrative Science Quarterly, 58(4), 624–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839213510151

Duan, J., Xu, Y., & Frazier, M. L. (2019). Voice climate, TMX, and task interdependence: A team-level study. Small Group Research, 50(2), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496418805855

Dutton, J. E., Ashford, S. J., O’Neill, R. M., Hayes, E., & Wierba, E. E. (1997). Reading the wind: How middle managers assess the context for selling issues to top managers. Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), 407–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199705)18:5<407::AID-SMJ881>3.0.CO;2-J

Eagly, A. H., Makhijani, M. G., & Klonsky, B. G. (1992). Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.3

Edmondson, A. C. (1996). Learning from mistakes is easier said than done: Group and organizational influences on the detection and correction of human error. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886304263849

Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Speaking up in the operating room: How team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1419–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386

Edmondson, A. C., & Harvey, J.-F. (2018). Cross-boundary teaming for innovation: Integrating research on teams and knowledge in organizations. Human Resource Management Review, 28(4), 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.03.002

Edmondson, A. C. (2020). When employees are open with each other, but not management. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/01/when-employees-are-open-with-each-other-but-not-management

Ellis, A. P. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Mai, K. M. (2021). The impact of supervisor–employee self‐protective implicit voice theory alignment. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, joop.12374. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12374

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. Plenum Press.

Farh, C. I. C., & Chen, G. (2018). Leadership and member voice in action teams: Test of a dynamic phase model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000256

Farh, C. I. C., Oh, J. K., Hollenbeck, J. R., Yu, A., Lee, S. M., & King, D. D. (2019). Token female voice enactment in traditionally male-dominated teams: facilitating conditions and consequences for performance. Academy of Management Journal, amj.2017.0778. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0778

Fast, N. J., Burris, E. R., & Bartel, C. A. (2014). Managing to stay in the dark: Managerial self-efficacy, ego defensiveness, and the aversion to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 57(4), 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0393

Frazier, M. L., & Bowler, W. M. (2015). Voice climate, supervisor undermining, and work outcomes: A group-level examination. Journal of Management, 41(3), 841–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311434533

Frazier, M. L., & Fainshmidt, S. (2012). Voice climate, work outcomes, and the mediating role of psychological empowerment. Group & Organization Management, 37(6), 691–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112463960

Frese, M., Teng, E., & Wijnen, C. J. D. (1999). Helping to improve suggestion systems: Predictors of making suggestions in companies. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(7), 1139–1155. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199912)20:7<1139::AID-JOB946>3.0.CO;2-I

George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2001). When openness to experience and conscientiousness are related to creative behavior: An interactional approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.513

Girotra, K., Terwiesch, C., & Ulrich, K. T. (2010). Idea generation and the quality of the best idea. Management Science, 56(4), 591–605. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1090.1144

Hackman, J. R., Wageman, R., & Fisher, C. M. (2009). Leading teams when the time is right: Finding the best moments to act. Organizational Dynamics, 38(3), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2009.04.004

Harlos, K. P. (2001). When organizational voice systems fail: More on the deaf-ear syndrome and frustration effects. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 37(3), 324–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886301373005

Haselton, M. G., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Error management theory: A new perspective on biases in cross-sex mind reading. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(1), 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.81

Haselton, M. G., & Nettle, D. (2006). The paranoid optimist: An integrative evolutionary model of cognitive biases. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(1), 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1001_3

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hoyt, C. L., & Burnette, J. L. (2013). Gender bias in leader evaluations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(10), 1306–1319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213493643

Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41(7), 1854–1872. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471386

King, D. D., Ryan, A. M., & Van Dyne, L. (2019). Voice resilience: Fostering future voice after non-endorsement of suggestions. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(3), 535–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12275

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Detert, J. R., Treviño, L. K., & Edmondson, A. C. (2009). Silenced by fear: The nature, sources, and consequences of fear at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2009.07.002

Knoll, M., Neves, P., Schyns, B., & Meyer, B. (2021). A multi-level approach to direct and indirect relationships between organizational voice climate, team manager openness, implicit voice theories, and silence. Applied Psychology, 70(2), 606–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12242

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Chao, G. T. (2012). Macrocognition, team learning, and team knowledge: Origins, emergence, and measurement. In E. Salas, S. M. Fiore, M. P. Letsky (Eds.), Theories of team cognition: Cross-disciplinary perspectives (pp. 19–48).

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Doherty, M. L. (1989). Integration of climate and leadership: Examination of a neglected issue. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(4), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.74.4.546

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the efectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Supplement, 7(3), 77–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.x

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Klein, K. J. (2000). A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: Contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In S. W. J. Kozlowski & K. J. Klein (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 3–90). Jossey-Bass.

Kramer, R. M. (1998). Paranoid cognition in social systems: Thinking and acting in the shadow of doubt. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(4), 251–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0204_3

Kuenzi, M., & Schminke, M. (2009). Assembling fragments into a lens: A review, critique, and proposed research agenda for the organizational work climate literature. Journal of Management, 35(3), 634–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308330559

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.2.326

Levy, S. R., Chiu, C., & Hong, Y. (2006). Lay theories and intergroup relations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 9(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430206059855

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. C., & Farh, J.-L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.10.014

Liu, W., Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2013). The relational antecedents of voice targeted at different leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(5), 841–851. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032913

Liu, W., Song, Z., Li, X., & Liao, Z. (2017). Why and when leaders’ affective states influence employee upward voice. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 238–263. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.1082

Luthans, F., & Stajkovic, A. D. (1999). Reinforce for performance: The need to go beyond pay and even rewards. Academy of Management Perspectives, 13(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1999.1899548

Martinko, M. J., Mackey, J. D., Moss, S. E., Harvey, P., McAllister, C. P., & Brees, J. R. (2018). An exploration of the role of subordinate affect in leader evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(7), 738–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000302

Mathieu, J. E., & Chen, G. (2011). The etiology of the multilevel paradigm in management research. Journal of Management, 37(2), 610–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310364663

Maynes, T. D., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2014). Speaking more broadly: An examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(1), 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034284

Milliken, F. J., Morrison, E. W., & Hewlin, P. F. (2003). An exploratory study of employee silence: Issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1453–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00387

Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (1999). The structure and function of collective constructs: Implications for multilevel research and theory development. Academy of Management Review, 24(2), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.1893935

Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2011.574506

Morrison, E. W. (2014). Employee voice and silence. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Morrison, E. W., Wheeler-Smith, S. L., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020744

Morrison, E. W., See, K. E., & Pan, C. (2015). An approach-inhibition model of employee silence: The joint effects of personal sense of power and target openness. Personnel Psychology, 68(3), 547–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12087

Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413

Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2011). Human threat management systems: Self-protection and disease avoidance. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(4), 1042–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.08.011

Ogunfowora, B., Stackhouse, M., Maerz, A., Varty, C., Hwang, C., & Choi, J. (2020). The impact of team moral disengagement composition on team performance: The roles of team cooperation, team interpersonal deviance, and collective extraversion. Journal of Business and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09688-2

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Randall, K. R., Resick, C. J., & DeChurch, L. A. (2011). Building team adaptive capacity: The roles of sensegiving and team composition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022622

Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392563

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.109

Schneider, B., & Reichers, A. E. (1983). On the etiology of climates. Personnel Psychology, 36(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1983.tb00500.x

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2001). A social capital theory of career success. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 219–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069452

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2012). Ask and you shall hear (but not always): Examining the relationship between manager consultation and employee voice. Personnel Psychology, 65(2), 251–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01248.x

Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(3), 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500

Tett, R. P., & Guterman, H. A. (2000). Situation trait relevance, trait expression, and cross-situational consistency: Testing a principle of trait activation. Journal of Research in Personality, 34(4), 397–423. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2000.2292

Tett, R. P., Toich, M. J., & Ozkum, S. B. (2021). Trait activation theory: A review of the literature and applications to five lines of personality dynamics research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8, 199–233. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-062228

Turner, N., Tucker, S., & Deng, C. (2020). Revisiting vulnerability: Comparing young and adult workers’ safety voice intentions under different supervisory conditions. Accident Analysis & Prevention, 135, 105372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2019.105372

van Kleef, G. A., Heerdink, M. W., Cheshin, A., Stamkou, E., Wanders, F., Koning, L. F., Fang, X., & Georgeac, O. A. M. (2021). No guts, no glory? How risk-taking shapes dominance, prestige, and leadership endorsement. Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000868

Waller, M. J., Okhuysen, G. A., & Saghafian, M. (2016). Conceptualizing emergent states: A strategy to advance the study of group dynamics. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 561–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1120958

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

Wei, X., Zhang, Z.-X., & Chen, X.-P. (2015). I will speak up if my voice is socially desirable: A moderated mediating process of promotive versus prohibitive voice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(5), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039046

Weiss, M., Kolbe, M., Grote, G., Spahn, D. R., & Grande, B. (2018). We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.002

Withey, M. J., & Cooper, W. H. (1989). Predicting exit, voice, loyalty, and neglect. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34(4), 521. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393565

Yang, J., Lee, H. W., Zheng, X., & Johnson, R. E. (2021). What does it take for voice opportunity to lead to creative performance? Supervisor listening as a boundary condition. Journal of Business and Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09726-z

Zohar, D. (2002). The effects of leadership dimensions, safety climate, and assigned priorities on minor injuries in work groups. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(1), 75–92.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the 2018 annual conference of the Academy of Management. We would like to thank Jana Raver, Julian Barling, and Matthias Spitzmuller for their constructive comments and insightful feedback on this research.

Funding

This research was supported by funding provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Odette School of Business. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Academy of Management 2018 annual conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brykman, K.M., Maerz, A.D. How Leaders Inspire Voice: The Role of Voice Climate and Team Implicit Voice Theories. J Bus Psychol 38, 327–345 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09827-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-022-09827-x