Abstract

This study identifies the impact of Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) on foreign direct investments (FDI) by taking advantage of the random timing of 44 unilateral BIT terminations in India between 2013 and 2019. Using quarterly bilateral data of 138 foreign investors’ home countries (FIHCs), our difference-in-differences (DD) estimates uncover a significant reduction in FDI inflows to India in response to BIT terminations by more than 30 percent compared to countries without terminations. We identify the sudden break with investor protection for new investments as the major transmission channel. Further investigations suggest that investors do not necessarily abandon India in response to BIT terminations but apparently reroute FDI via FIHCs with BITs. Evidence from firm-level data reveals that investors revoke or reroute mainly deals (e.g. mergers and acquisitions) rather than own new projects. Moreover, similarity of some legal institutions with India offsets the negative effect of BIT terminations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Until 2019, more than 10 percent of all ratified Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) worldwide have been terminated.Footnote 1 BIT terminations began slowly in the 2000s and temporarily peaked in the year 2017, where we saw more BITs terminated than newly adopted.Footnote 2 While the signing and ratification of BITs have gained considerable attention by scholars,Footnote 3 BIT terminations have yet been largely neglected.

In this paper, we address a rich and controversial debate on the impact of BITs on FDI.Footnote 4 One reason for controversy is the endogeneity in this relationship (Aisbett, 2009; Busse et al., 2010). A sequence of 44 unilateral BIT terminations in India provides a unique setting, which enables us to tackle this empirical challenge with a new way of identifying the impact of BITs on foreign direct investments (FDI).Footnote 5 With the sudden decision to unilaterally terminate BITs in the early 2010s, India provides not only the largest concentrated effort but also a pattern of heterogeneous timing of BIT terminations, which enables us to compare FDI inflows from several groups of foreign investors’ home countries (FIHCs) with BITs in force, BITs terminated and no BITs. In addition, we show that the specific setting of BIT terminations in India fulfills the necessary conditions for the use in quasi-experimental designs like difference-in-differences (DD). In doing so, it enables us to address an important empirical gap, which is of great interest to researchers and policy makers.

Treatments in DD require to be ‘as good as random’ (for example, Bertrand et. al. 2004, p. 250). Although the main reason for large-scale terminations of BITs was an increasing number of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) claims,Footnote 6 the terminations have not been directed towards the home countries of disputing foreign investors. Instead, India made a general decision to terminate all BITs, beginning with Argentina in 2013. Effective termination of all BITs, however, could not have been invoked immediately because the earliest possible termination dates of BITs were in most cases after the decision to terminate all BITs and they had occurred rather heterogeneously. This is further reinforced by the original ratification date, the treaty terms about minimum duration, extension of BITs, and the fact that these termination dates cannot be manipulated at the time of the termination decision. The ratification and treaty terms had been determined years, often decades before this decision. This set up paired with evidence that (almost without exception) FIHCs government were not spared from termination as soon as they became eligible for termination, makes BIT terminations plausibly exogenous to India-specific and FIHC-specific factors and makes them a good candidate for DD applications. Similar exogeneity claims have been made for the participation in the electricity rebate program in California due to the ‘eligibility rule’ (Ito, 2015), the change in Chinas’ FDI regulations due to WTO accession negotiations (Lu et al., 2017) or political leaders meeting the Dalai Lama due to his travel patterns (Fuchs & Klann, 2013).

The use of DD is likewise justified by the fact that terminations do not appear to be influenced by the extent of past FDI activity from a specific FIHC government or other economic factors. Unilateral BIT terminations were directed against all categories of FIHCs, which include very large FIHCs and historically important allies. Moreover, the perspective of BIT termination has another advantage because it triggers an abrupt break with investor protection of an existing BIT. This is different from the effect of BIT ratification, because the exact time window for possible adjustments of investment behavior is difficult to determine (Berger et al., 2013; Egger & Merlo, 2007). New foreign investments conducted after the BIT termination date, for example, cannot rely on ISDS procedures to enforce their rights against violations by public officials. For this reason, we expect that after the termination date, foreign investors from the affected BIT partner countries will instantaneously reduce new investments. Taken together, the randomization by hetrerogenous ratifcation and treaty terms (e.g. honeymoon phase, automatic renewal) for BIT terminations, the independence of BIT terminations in India from bargaining power of FIHCs or other bilateral factors and the instantenous break with investor protection by an exisiting BIT make us confident that the use of DD is valid in our setting.

The hetrerogeneity of the timing of BIT terminations, however, is challenging for the application to quasi-experimental methods, as it potentially introduces biases into the classic two-way fixed effects DD estimators. Fortunatley, we can rely on the recently proposed Goodman-Bacon decomposition (Goodman-Bacon, 2018) and Wald DD-estimators (De Chaisemartin & D'Haultfaeuille, 2018), which are both capable of identifying the average treatment effect in the presence of heterogeneous timing of the treatment itself. Morevover, the heterogeneous timing enables us to investigate the impact of BIT terminations on FDI by comparing multiple BIT termination groups (‘timing’ groups) with FIHCs with a BIT (‘always’ group) or without a BIT (‘never’ group) throughtout the whole time frame of this study.

The focus on a single country enables us to discuss the data quality of bilateral FDI panel data. In the many-to-many cross-country studies, data sources have incomplete records and suffer from different reporting standards and divergent FDI definitions (Blonigen & Piger, 2014; Chakrabarti, 2001; Schneider & Frey, 1985; Tomlin, 2000). A single country view as a reference point has been used to point out consistent reporting standards and quality of data in studies concerned with bilateral FDI. Studies with a single reference country have been conducted for the US (Haftel, 2010; Salacuse & Sullivan, 2005), Germany (Egger & Merlo, 2012), and Spain (Rodriguez & Pallas, 2008), and have been widely acclaimed. Moreover, we use firm-level data as an alternative data source to estimate the effect of BIT terminations in India and in addition assess whether BIT terminations do affect different types of investments equally.

Finally, India is not the only country with BIT terminations. We have chosen India due to a unique sequence and timing of a high number of unilateral BIT terminations, the availability of multiple data sources, the substantial volumes of FDI (e.g. compared to other BIT termination countries like Ecuador, Bolivia) and the fact that BITs are not complemented by other supranational institutions (e.g. the European Union in case of BIT terminations of Italy and Poland).

Based on quarterly aggregate FDI inflows of 138 FIHCs and 44 unilateral BIT terminations between 2013 and 2019, we find that terminations have significant and substantial negative effects on FDI inflows. In our preferred specification, the termination of a BIT is equivalent to a more than 30 percent decrease in FDI inflows compared to the ‘always’ and ‘never’ BIT groups. These results remain broadly stable when we account for heterogeneous timing, FIHC-specific time trends or pre-treatment trends, and across several specification checks.

Further investigations reveal that BIT terminations do not impose this significant negative effect on the ‘never’ and ‘always’ BIT groups, which suggests that the direct effect found in the baseline estimates is likely due to the termination of BIT-based investor protection and not due to a signal of general anti-FDI sentiments. In further tests, we evaluate the impact of the quality of domestic institutions on the effect of BIT terminations on FDI, the effect of BIT terminations of different types of investment (using firm-level data) and investigate the possibility of rerouting of FDI from BIT termination FIHCs to BIT FIHCs. Here we find that similar efficiency of the court systems of the FIHCs and India significantly reduces the negative effect of BIT termination, that foreign investor firms abandon deals (i.e. mergers and acquisitions (M&As) and buyouts) rather than own new projects, and that investors do not necessarily abandon India as FDI destination but apparently reroute substantial FDI flows to India via other FIHCs with a valid BIT. This is consistent with our predictions that BIT-based investor protection is highly important to foreign investors.

Our study contributes to a better understanding of the role of BITs in attracting FDI. To this end, we exploit a new angle, which allows for better identification of the effect of BITs as determinant of FDI activity. Termination properties in case of India enable us to exploit the variation in instantaneous treatment effects over time and to address endogeneity concerns, which are commonly found in studies of BIT ratification. While others used dynamic panel estimators and matching (Egger & Merlo, 2012; Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2011), we exploit the properties of BIT terminations for DD applications. While there are DD applications with bilateral FDI data, for example in the context of financial development (Bilir et al., 2019; Desbordes & Wei, 2017) or environmental regulations (Cai et al., 2016), there are no comparable applications of DD concerning the effect of BITs on FDI activity. Moreover, existing studies have addressed the determinants of BIT ratification (Bergstrand & Egger, 2013) and renegotiation (Haftel & Thompson, 2018), but they have not yet addressed the economic consequences of BIT terminations. We found several studies by legal scholars (Calvert, 2018; Carska-Sheppard, 2009; Lavopa et al., 2013) but are, to the best of our knowledge, not aware of any economics research on BIT termination.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the existing literature and postulates the expected effect of BIT terminations on the flow of foreign direct investment. Section 3 presents the identification strategy. Section 4 discusses the data and sample used in our analysis. Section 5 proceeds with the results. Section 6 presents some robustness checks. Section 7 explores the transmission mechanisms. Section 8 concludes.

2 BIT termination and the expected effects on FDI in India

2.1 BIT Terminations and FDI in India

India has steadily ratified BITs between 1994 and 2014. In the early 2010s, India began reviewing its strategy and began pressuring their BIT partners to renegotiate most of these treaties to align the existing BIT to a new model BIT. This policy shift was not well received by the investors. Therefore, India chose to unilaterally terminate its BITs. It initially notified 58 out of 87 BIT partners about the unilateral terminations. Until the year 2019, the number of notified countries has grown to 68.Footnote 7 This leaves only 21 BITs in force.

India did not terminate all investment treaties at the same time. It started termination with Argentina at the end of 2013, followed by 4 terminations in 2016 and 37 in 2017 and again 4 terminations in 2018. Further terminations were due in the second half of 2019. Table 1 provides a detailed overview of all BIT terminations and the ‘always’ and ‘never’ BIT countries, which have been recorded as investors to India.

The main purpose of BIT terminations appears to be the re-negotiation of BITs after an increasing number of expensive ISDS claims invoked by international investors against India in the early 2010s.Footnote 8 In turn, Indian officials introduced a new model BIT with a more restrictive definition of who qualifies as a foreign investor, less extensive investor rights, and a new process for handling disputes about investor rightsFootnote 9 in 2015. By the end of 2018, none of the FIHCs, which either had terminated or kept their BIT, had ratified the new model BIT.Footnote 10

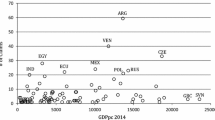

During the same time span, the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry has reported FDI inflows from 144 FIHCs. Singapore and Mauritius provide the largest fraction of FDI inflows to India with 28 percent and 27.6 percent of all reported FDI inflows during the period between 2013 and 2019. Highly beneficial double taxation treaties and confidence in the judiciary and contract enforcement has historically established Mauritius and Singapore as attractive hubs for investments to India for many investors around the world. In general, the aggregate FDI inflows to India have grown until 2015, while the trend flattened out thereafter and even began to decrease after 2016 (see Fig. 1).

2.2 The expected effect of BIT Terminations on FDI inflows

There are many determinants of FDI flows. While India shows an improvement in its general business environment over the same time span of our study, a sudden plummet of annual FDI inflows after 2016 can be observed (see Fig. 1). We argue that the termination of BITs is an important factor, which does explain this discrepancy.

Without the loss of generality, the key hypothesis developed in this paper is that BIT terminations lead to an immediate and sustained drop in FDI inflows from FIHCs affected by these terminations. A plausible explanation is that the instantaneous absence of BIT-based extended investor protection to new investments makes investors less confident about the security of their assets and therefore they tend to reduce new investment activity in favor of alternatives. ISDS procedures are working independently from the domestic institutions of the FDI host country and are therefore valued by international investors with higher levels of FDI activity (Aisbett et al., 2018; Berger et al., 2011; Egger & Pfaffermayr, 2004; Frenkel & Walter, 2019; Hallward-Driemeier, 2003; Nichols, 2018).Footnote 11 If the investors initially valued BIT-based investor protection, a sharp break with this investor protection at the termination date is expected to immediately deplete FDI inflows.

Besides the legal aspect of investor rights, the number of BITs ratified by a country also signals investor-friendliness of that host country. The extended rights offered to investors from BIT partner countries suggest commitment to the protection of foreign investments and pro-investor policies (Büthe & Milner, 2009, 2013; Colen et al., 2016; Rose-Ackerman, 2009; Salacuse & Sullivan, 2005; Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2011). In this regard, BIT terminations, in particular if the number of terminations accumulates during a reasonably short period, are expected to signal growing hostility and anti-FDI sentiments and therefore they probably deter FDI.

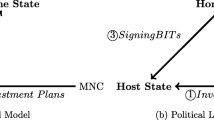

The expected responses of investors to BIT termination differ for these two channels. If the BIT as legal instrument of investor protection is the main concern of investors, a reduction in FDI activity is expected only after the effective termination of the protection of these rights for investors after the actual termination date. If BIT termination signals anti-investor sentiment, we expect FDI activity to drop either after the initial announcement of (large-scale) BIT terminations or after the first BITs had been effectively terminated. The main difference is that the legal instrument argument would show a change in investor activity only after the BIT of the FIHC has been effectively terminated, while in cases of the anti-investor sentiment, a general overall decrease in activity should affect all investors after the BIT termination policy has been made credible (e.g. communication at an official press conference, notification of investors about the BIT termination, first effective termination). The main difference in empirical patterns for the two alternative channels is that in case of the legal instrument argument, the response of investors to termination of a BIT should sharply change after the effective termination date of the BIT protecting the investors’ assets, while in case of anti-investor sentiment, most investors would react immediately after the announcement of (large-scale) BIT terminations because they already expect anti-investor sentiment in the near future.

Finally, the quality of domestic legal institutions is an important reference point because BITs contain terms and procedures, which potentially act as substitutes for domestic institutions. Legal scholars argue that investors rely on BITs with international arbitration provisions because they enable investors to circumvent slow and biased domestic courts (Ginsburg, 2005; Schreuer, 2011). We expect that the negative effect of BIT terminations on FDI does diminish, if the quality of legal institutions in the FIHC country is similar to that in the host country. A plausible explanation is that investors with a similar quality of legal institutions are better equipped for the specific challenges of the domestic legal environment, after BIT protection suddenly ends.

We begin our empirical analysis by investigating the instantaneous legal effect of BIT terminations to obtain baseline results. Thereafter we explore the alternative channels, terminations as negative signals, the role of domestic institutions and possible transmission channels, in Sect. 7.

3 Identification strategy

3.1 Baseline setup

Our goal is to examine the contribution of terminating BITs to the flow of FDI consistently. To this end, we exploit the timing of BIT terminations as a source of variation in the FDI inflows. Our identification strategy relies on pre-termination trends, which we exploit by using a simple DD estimator. In this respect, we augment the simple 2 × 2 DD empirical specification with multiple groups and multiple time periods (Bertrand et al., 2004; Hansen, 2007a, 2007b; Imbens & Wooldridge, 2009):

where \(y\) is the FDI inflow of i-th investor in t-th year-quarter to India. The key coefficient of interest is \(\hat{\beta }\) which denotes the impact of BIT termination M. The treatment effect is measured with a dummy variable, which indicates one if an FIHC government i has no BIT in a year-quarter t and zero otherwise. This coding is opposite to most other studies but is intentional because the coefficient 2 × 2 DD fixed effect estimator can be interpreted as the effect of BIT termination.

The term \(\gamma\) captures the investor-level heterogeneity bias that is unobserved, and \(\lambda\) denotes the set of time-varying common FDI technology shocks common to all home countries of foreign investors to India. The vector X contains the covariates capturing time-varying investor characteristics. In studies with large numbers of zeros and the presence of heteroscedasticity, the reliance on the Poisson pseudo-maximum likelihood (PPML) with clustered standard errors is recommended (Head & Mayer, 2014; Santos Silva & Tenreyro, 2006; Westerlund & Wilhelmsson, 2011). In panels, it delivers consistent and unbiased estimates with reasonably large number of groups and time periods (Fernandez-Val & Weidner, 2016). In the following sections we discuss the identifying assumptions, major challenges and outline important checks, which help us to test validity of our approach in case of BIT termination.

3.2 Exogeneity and quasi-randomization of BIT termination

To understand whether the exogeneity and random occurrence of BIT terminations in India is a plausible assumption, we require detailed knowledge about the termination decision and the effective termination dates.

The ratifications of BITs have often been done as a response to the prospect of large volumes of investments. However, BIT terminations in India have different reasons and appear not to be a direct response to FIHC specific factors. In India, the main rationale behind termination was the increasing number of BIT-based ISDS claims and the urge of India to introduce a new model BIT, which limits the scope of investors rights and gives India more space for regulation and policy making (Ranjan, 2019). Terminations were not directed against the few foreign investors involved in ISDS procedures against India. It was instead a general decision to terminate all BITs.Footnote 12 An example is the ISDS case won by an Australian investor in 2011. Indian officials have singled out this case as a reason for the revision of their BIT strategy, but it did not lead to the termination of the Australian BIT until March 2017, while the first termination in August 2013 against Argentina did happen without any previous ISDS claim or any other dispute.

Moreover, BIT terminations in India are by themselves not directly related to contemporaneous foreign investor relations such as high FDI stocks or recent FDI inflows. Sparing important BIT partner countries (for example, Mauritius and Singapore) from BIT termination would be an indication of a strategic termination decision. Moreover, having FIHC governments with high bargaining power on one side (e.g. BIT) and less powerful FIHCs on the other side, would also be an indication that termination is not ‘as good as random’. Looking at the effective termination in the case of India, we see that FIHCs with high bargaining power end up in different groups. Investigating such cases, we find Singapore with a ratified BIT in place while Mauritius experienced an effective termination of its BIT in the year 2017. A rather heterogeneous set of ratification dates, durations of the treaties and sunset clauses of countries with arguably high bargaining power (France May 2000, Netherlands December 1996, Spain December 1998, Italy March 1998 etc.) left these countries with different effective termination dates within a few months of the announcement of the general decision (e.g. France 2017Q2, Spain in 2016Q3, Netherlands 2016Q4, Italy 2017Q1) and others after longer time spans (e.g. China: BIT ratification in August 2007 and BIT termination in late 2018) (for an overview of the distribution of ratification year, treaty duration and sunset clause duration, see Table 2).

Figure 2 shows an overview of the three groups of FIHCs plotted in order of the aggregate FDI inflows between 2013 and 2019 by the three different groups. In addition to our investigation of ratification dates, renewal procedures, and the announcement timing, the pattern derived from ordering FIHCs by aggregate FDI inflows from larger to smaller does not appear to indicate bias towards FIHCs with high bargaining power in any of the groups (‘never’, ‘always’ and ‘timing’).

In fact, the critical factors for effective termination are the decision to terminate all BITs and the expiration date of each individual BIT. The expiration date depends on treaty terms of the BITs like minimum duration (‘honeymoon phase’), extension and termination rule along with their original ratification date. In India, the ‘honeymoon phase’ amounts to 10 years for 72 FIHCs, 15 years for seven FIHCs, and indefinite for eight FIHCs of all 87 BITs. After this phase, BITs had been up for automatic renewal for either an indefinite period, or 10 to 15 years. The expiration of the ‘honeymoon phase’ is a necessary condition for unilateral BIT termination.

Due to the fact that many BITs had been ratified at different times, often decades ago, and that treaty terms considerably vary among BITs, and given the arbitrary decision to terminate all BITs at the earliest possible termination date, we argue that effective BIT terminations have been randomized in case of India. Some BITs were terminated soon after the decision, others followed later and some are still in force today. This does not only introduce randomization but also enables us to make comparisons of FIHCs with and without BITs over the whole time period (‘always’, ‘never’ groups), and conduct comparisons of BIT terminations at different points in time (‘timing’ groups).

The BIT terminations between 2013 and 2018 were conducted with remarkable rigor and in almost each case were implemented exactly at the earliest possible termination date. When looking at the timing, almost all BITs were unilaterally terminated as soon as they exceeded the initial or renewal period.Footnote 13 By the end of 2018, 68 BITs were terminated and 19 remained in force. These active BITs, with the exception of Philippines and Singapore, had not been eligible for unilateral termination.

Based on this evidence, and the fact that it is impossible to manipulate the ratification dates and treaty terms or anticipate the termination decision in 2013, decades earlier when the treaty terms were determined and ratified, we argue that BIT terminations are plausibly exogenous to India-specific and FIHC-specific factors.Footnote 14 Further concerns of non-random selection are addressed by including additional time-varying control variables to account for observable differences between FIHCs. In addition, we rely on further tests to check on the identifying assumptions by adding FIHC-specific linear and quadratic time trends and removing pre-treatment trends (see Sect. 6.1.1).

3.3 BIT termination as sharp break from existing investor protection

BIT termination posits an instantaneous and reasonably sharp break from existing investor protection at a clearly defined date. After the passing of this date, violations of investor rights of new investments are legally handled by domestic courts. For the estimation of the effect of BITs, the termination perspective has a considerable advantage over the ratification perspective. While newly ratified BITs predictably remain effective over longer time spans, FDI behavior does not necessarily have to adjust instantaneously. Unilateral termination rules in the BIT obliged India to notify BIT partner countries a year in advance of the effective termination date. This rule could lead to an anticipation effect of a deterioration of conditions for foreign investors (investor protection, general hostility), which makes it more difficult to identify the treatment effect at the termination date. We do not expect such a behavior due to the ‘sunset clause’ contained in the Indian BITs. It protects all investments conducted before BIT termination for an extended period of 5 to 20 years after the termination date. The effect of the notification of the termination, if anything, could trigger an increase in FDI inflows to India before the effective termination date. For the treatment effect, however, we expect a substantial and instantaneous drop in FDI inflows in response to effective BIT termination. Aside of these expectations, we address these concerns about anticipation by conducting placebo tests (Sect. 6.1.2).

3.4 BIT termination as heterogeneous treatment

As Table 1 has shown, BIT termination in India had been heterogeneously scattered over different quarters between 2014 and 2018. Heterogeneity in the treatment effects does potentially introduce bias to the two-way fixed effects estimatorFootnote 15 (De Chaisemartin & D'Haultfoeuille, 2020; Imai & Kim, 2019). In this regard, addressing this problem requires a better understanding of the sources of the heterogeneity, which can—aside of heterogeneity in timing – also be heterogeneity in magnitude of the treatment over time. Hence a deeper understanding of the heterogeneity is important to understand the validity of the estimators, which are available for such as setting.

In our case, the terminations are stable and have a sustained legal effect. Although having some differences, the scope of coverage of Indian BITs is remarkably consistent with respect to important cornerstones of investor protection. ISDS provisions, expropriation clauses and full protection and security are included in all 87 Indian BITs. Fair and equitable treatment (85), National Treatment (84) and Most Favored Nation Clauses (81) are included in most Indian BITs. Looking deeper into ISDS there are 10 countries with security exception clauses, and another three exclude certain policy areas from ISDS and one has limitations to the provisions of ISDS (Slovakia). Despite these few deviations, we assume that the BITs to India are remarkably similar in the composition of treaty terms and the strength of ISDS provisions.Footnote 16 Moreover, after India had terminated BITs, the legal situation changed immediately and this change did not alter any further over the whole time period under consideration. The scope of the treatment effect is stable because BIT termination has the same consequences for investor protection rights at any year-quarter period. Therefore, we address heterogeneity in timing, for which we are able to rely on two recently introduced estimators, which are now briefly introduced

3.4.1 Decomposing the treatment effect using Bacon-Goodman approach

Given the variation in the timing of BIT terminations, the fixed-effects DD estimator from Eq. (1) is most likely contaminated by FIHC-specific time trend in FDI inflows induced by the termination itself. One way to address this problem is the recently introduced Goodman-Bacon (2018) decomposition. In its simplest version, \(\hat{\beta }^{DD}\) consists of the weighted average of all DD parameters of all possible 2 × 2 period comparisons. Compared to the original specification in Eq. (1), which only effectively compares treated and non-treated FIHCs, the decomposition exploits several comparisons of groups being treated earlier and later over the period in question. For these comparisons, we apply the specifications as in Eq. (1) but replace the 2 × 2 two-way fixed effects DD estimator

where \(y\) represents the FDI inflow from investor i at time t, M denotes again the dummy variable which indicates BIT termination by switching from 0 to 1 or remains constant otherwise, and X is a vector of time-varying covariates. Given the \(k = 1,2, \ldots K\) range of possible treatment-period interactions, we deploy specifications with different treated and untreated groups. Besides the ‘timing’ groups ‘early’ (k) and ‘late’ (l) termination, we also consider a group of never (U) and always (A) treated groups. The ‘never’ and ‘always’ treated groups represent the countries, which have a valid BIT in place throughout the whole timespan and is therefore never treated with termination while the always group are the FIHCs, which have never ratified a BIT in the first place. The decomposed treatment effect contains the following two-by-two estimators (\({\beta }^{2x2})\) and weights (S):

In the two-way fixed effects specification the estimate of \({\hat{\beta }}^{DD}\) (2) is the ‘variance- weighted average treatment effect on the treated’ (VWATT) and represents the ‘ weighted average of all possible two-by-two DD estimators’. According to Goodman-Bacon (2018: p. 8) they are defined as following:

The superscripts stand for the subperiods after (‘Post’), and before (‘Pre’) treatment as well as at the time window when the ‘treatment status varies’ (‘Mid’) (Goodman-Bacon, 2018: p. 6). For example, the values of the ‘early’ groups work as treatment while the ‘later’ groups in this setting serve as control groups (6). The weights S are determined by group sizes and treatment variance. The variance of treatment is largest for groups with timing of the treatment being in the middle of the time span of the study and the lowest weights are assigned to groups near the start and end points (Goodman-Bacon, 2018: p. 8–9).

Two key identifying assumptions for the validity requires the treatment effect to be stable over time which requires homogeneity and monotonicity. The first means that the treatment effect should not vary in intensity over time while the latter excludes the case where units switch in and out of treatment. As described in the properties of BIT termination in India, we have no FIHCs in our sample where the treatment effect changes in intensity over time and no FIHCs, which had terminated and resigned a new BIT during the time span of our study. Therefore, we expect that the Bacon-Goodman approach is valid in our case and that the estimator delivers unbiased estimates of the treatment effect.

3.4.2 Estimating the heterogeneous treatment with temporal correction

As another alternative, we compute the Wald DD and time-corrected Wald ratio (Wald TC) coefficients that are applicable for multi-group and multi-periods DD settings (De Chaisemartin & D'Haultfaeuille, 2018). To address the temporal correction, we calculate the coefficients for the multiple groups and multiple period case, which is weighted sum of coefficients at each year-quarter as the weighted average of the local average treatment effects (LATEs) of FIHCs switching treatment at any year-quarter. This implementation is straightforward, when the treatment is homogenous and monotonic over time. In fact, homogenous means that we can assume that the treatment rate of the treated is constant over time and monotonic requires that groups do not switch repeatedly in and out of treatment (de Chaisemartin & D’Haultfoeuille, 2017). The termination of BITs is homogenous, because it becomes effective at a clearly defined date and maintains constant until a new BIT is ratified. Monotonic treatment holds in our case because, there were no new ratifications which replace formerly terminated BITs terminations.

Another important assumption in our setting is ‘conditional common trends’, which is more credible than assuming just ‘common trends’ for estimating the Wald estimators in presence of multiple groups and heterogeneous treatment (de Chaisemartin & D’Haultfoeuille, 2017). We control for the covariates, which influence the pre-treatment dynamics of the outcomes. Herewith, we precisely rely on the covariates to balance FIHCs in treatment and control groups in the pre-treatment period with propensity score matching. We calculate the standard errors by using cluster bootstrapping. This procedure paired with the fact that our setting matches well with the required assumptions of the Wald DD estimator and the Wald DD with temporal correction, make us confident that the use of these estimators is valid and that the results are unbiased.

For better comparability of the results, we use the same three sets of subsamples for the two Wald estimators as for the Bacon decomposition and add the same control variables.

4 Data

We obtain the quarterly bilateral FDI inflow data from SIA newsletters of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) of the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry (IMCI) for the period 2013 to mid-2019.Footnote 17 In the baseline estimates with PPML, we use the values in Million US-Dollars,Footnote 18 while in specifications in which this estimator is not available, we use the inverse hyperbolic transformation on FDI inflows in US-$ (Aisbett et al., 2018).

The FDI inflow data consist of FDI equity inflows of the Automatic Route (largest fraction which requires no government or Reserve Bank of India approval), Approval Route via the Ministry of Finance and Foreign Investment Promotion Board (FIPB) (mostly Banking, Telecom, Power etc.), acquisition of existing shares, and equity capital of unincorporated bodies. Bilateral FDI data in general is messy. The specific problems are hard to come by in cross-country studies of bilateral FDI. For the Indian data of the DPIIT, omissions and delays in reporting have been detected (Rao et al., 2018). Such delays likely hurt the ability of our estimator to detect sharp FDI responses to sudden policy changes, because the delays in reporting and omission are very unlikely to be exactly tied systematically to temporally heterogeneous BIT terminations. Based in the insights about the nature of the biases in the DPIIT bilateral FDI data, we carefully interpret our results in the light of this knowledge. In addition, we later challenge our results by re-estimating our baseline models based on an alternative firm-level data source for the same time span (2013–2019).

The full sample contains FDI inflows from 144 investor-countries for which 47.7 percent of the investor-quarter pairs report non-zero inflows. The treatment effect is measured with a dummy variable, which indicates one if an investor i has no BIT in a year-quarter t and zero otherwise. Looking at this over time, we end up again with our three distinct groups of FIHCs.

The FIHCs in the ‘timing’ group have a BIT ratified before 2013, but experience termination at any year-quarter t after 2013 and before 2019. In our sample of bilateral FDI flows, this group holds 44 FIHCs.Footnote 19 These are FIHCs with termination of ratified BITs and without any complementary investment agreement with investor protection provisions. The 18 ‘always’ BIT partner countries have a BIT ratified before 2013 and in force until at least the second quarter in 2019, which means that they do not experience a termination of their BIT over the entire period of our study. We observe only one newly ratified BIT by United Arab Emirates in 2014.Footnote 20 All BITs in our sample include ISDS provisions. The remaining 75 FIHCs deploy FDI inflows to India but have never had a treaty ratified during the entire time span and are therefore grouped as ‘never’ BIT group.

We exclude some countries from the baseline estimates because they appear to be ambiguous cases. First, Malaysia and South Korea are countries, which have their BIT terminated but they still have a valid Treaty with Investment Provisions (TIP) with India in place. The two FIHCs could be either classed in the ‘always’ or ‘timing’ groups. Second, Ghana, Nepal, Seychelles, and Djibouti are excluded because they have had a BIT terminated, which has only been signed but never ratified. We remove all the ambiguous cases from the baseline estimates, which leaves us with 44 ‘timing’, 18 ‘always,’ and 75 ‘never’ BIT FIHCs and only one new ratification, which in total amounts to 138 all FIHCs.

Following existing studies, we add covariates reflecting the size and structure of the economy of the FIHCs. We take the logarithm of the expenditure side annual real GDP from Penn World Tables 9.1 and the GDP per capita as well as the real GDP growth from the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI). They reflect the size of the economy and the degree of economic development. All covariates are lagged by one year.

As an alternative, we also estimate specifications with control variables, which are available on a quarterly basis. We use the first lag of the year-quarter for international liquidity, the trade balance with India form the International Financial Statistics (IFS) of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Uncertainty Index (WUI) (Ahir et al., 2018). In addition, we account for dyadic disputes by using a dummy variable, which equals one if in a quarter a firm from the same FIHC filed an ISDS claim (UNCTAD, 2019) against India, and zero otherwise. This indicator measures the bilateral hostility against the respective FIHCs. All quarterly reported covariates are lagged by one quarter. Table 3 provides the descriptive statistics of all variables used in the baseline and robustness specifications.

5 Results

The baseline results consist of the parsimonious model of the regression-based DD model with FIHC and year-quarter dummy variables and covariates. These are followed by the new DD estimators for heterogeneous timing before we provide evidence on the assumptions needed for these empirical settings and further robustness checks.

5.1 Two-way FE DD estimates

In columns (1) and (2) of Table 4, we show the results of the regression-based DD estimates with investor and year-quarter fixed effects for the full sample. The results show substantial negative and significant coefficients for BIT terminations. In columns (3) through (6), we add control variables to our original parsimonious baseline model. We find a highly significant negative effect of BIT terminations on FDI inflows. The magnitude of a reduction of more than 30 percent is in the range of what has been found by seminal contributions in this field (Neumayer & Spess, 2005; Aisbett et al., 2018). Overall, the baseline models can explain a substantial fraction of more than 90 percent of the variance in bilateral investment flows.Footnote 21

5.2 DD with Heterogeneous timing

Table 5 reports the Bacon decomposition results along with the results of the 2-way fixed effects estimates for comparison. We use a parsimonious specification with the same set of control variables for the full sample (columns 1 and 2), the sample with the ‘always’ group excluded (columns 3 and 4) and a sample restricted to only the ‘timing’ groups (columns 5 and 6).Footnote 22 The results show consistently negative and significant coefficients with similar sizes as the baseline results in Table 4.

The weights, which are calculated along with the decomposition estimators show that the treatment effect between ‘timing’, the ‘always’ and ‘never’ BIT groups are approximately half of the treatment effect of the timing groups. The weights for the average DD estimator in the full sample come to the largest degree from comparisons between the ‘timing’ groups and the ‘always’ and ‘never’ BIT groups. However, the highest negative coefficient is found for the comparison among the ‘timing’ groups. If we restrict the sample to comparisons of only the ‘timing’ groups, the overall coefficient raises from -0.19 to -0.31 while maintaining its significance level.

Table 6 shows the results of the Wald DD and the Wald TC estimates. The sample composition is the same as in the Bacon decomposition with one notable exception. Other than the Bacon estimator, the Wald estimators allow for switching of treatment in both directions. Therefore, we keep the United Arab Emirates in the sample.

For the full sample, we obtain a coefficient of more than double the size of the baseline estimates and the Bacon decomposition. The significance level for the Wald DD is at 0.05 and for the Wald TC estimator at the 0.1 level for the full sample and the ‘timing’ and ‘always’ BIT subsample respectively, while for the sample restricted to only ‘timing’ groups only the Wald DD maintains significance.

Recall that the DD estimator under Goodman-Bacon decomposition is a weighted average of all possible 2 × 2 group/period estimators taking advantage of the differential timing of the treatment. By contrast, Wald TC for the timing groups produces the difference in the underlying treatment effect because time is not a standard estimator. Since the treatment rate in our control group is stable, the trends in the counterfactual investment flows can be identified by considering the changes in mean outcomes across treatment and control samples over time. By adding these changes to the outcomes in the timing groups, we are able to recover the mean outcome for the switching countries, had they not changed their BIT status to termination over time. Since such adjustment yields a lower denominator for the temporal correction, given the absence of time as a standard instrument, the resulting coefficients are larger compared to Goodman-Bacon decomposed coefficients.

6 Robustness checks

6.1 Further investigations of the identifying assumptions

In the following section, we challenge the assumptions of our DD approach by controlling for FIHC-specific time trends, removing pre-treatment trends from the baseline specification, and implementing placebo-tests.

6.1.1 Assessing the common trend assumption

A challenge to the common trend assumption in the regression base multi-group and multi-period DD with heterogeneous treatment is adding group-specific time trends to the two-way fixed effects specification (Besley & Burgess, 2004). As long as the treatment effect remains significant under this specification, we can assume that BIT terminations and not unobserved FIHC trends influence the FDI inflows. In our case, the linear FIHC-specific time trends are the interaction of each FIHC with the year-quarter variable over the entire period of our sample. As done by similar studies, we also add quadratic time trends to account for the possibility that there is an unobserved non-linear trend among the FIHCs, which could alternatively explain the variation in FDI inflows. The results in Table 7 columns 1 and 2 show that after adding the FIHC-specific time trends, the coefficient substantially grows relative to the baseline results and becomes significant at the 0.01 level.

As an alternative to the group-specific time trends, we use a two-step procedure to remove pre-treatment trends (Goodman-Bacon, 2018). To this end, we add another eight quarters of FDI inflows to our sample, which leaves us with 10 pre-treatment quarters of FDI inflows between 2011 and the quarter of the first BIT termination by India with Argentina in August 2013. We restrict the sample to this pre-treatment period and estimate the baseline model including interactions of all timing groups and comparison groups along with linear time trends. We use the results to predict the residuals for the baseline sample between 2013 and 2019. In doing so, we obtain an outcome variable with the pre-treatment trends removed. In the second step, the outcome variable is used as dependent variable in an specification, which equals our baseline model. The results of the ‘pre-trend-adjusted estimator’ are consistent with the baseline estimates and are reported for the models with and without control variables in columns 3 and 4.Footnote 23 As the validity of the FIHC-specific time trends is known to rely on longer pre-treatment phases, we finally re-estimate the specification from column 1 with the extended dataset from 2011 to 2019 and again find consistent results.

6.1.2 Placebo test

The placebo tests should indicate significant differences between treated and untreated groups before treatment (Autor, 2003). In our case the change in FDI inflows between the ‘always’, ‘never’ BIT and ‘timing’ groups should not be significantly different from zero. For this purpose, we add 6 quarters of lead coefficients before the actual BIT termination and assess the persistence of the treatment effect by adding the same amount of lagged values.Footnote 24

We plot the point estimates of the Wald TC coefficients along with the 95% confidence intervals for all lead and lagged values centered around the treatment, which is indicated by zero on the horizontal axis. The plot reveals that the investors did obviously not anticipate treatment or change their investment behavior before the treatment relative to the other groups. All lead coefficients are insignificant. The coefficients turn significantly negative in comparison to the control groups and are relatively persistent through the quarters following the termination. This is consistent with the argument that investors respond to the effective legal change (e.g. absence of ISDS provisions) and not anti-investor sentiment signaled by the general decision to terminate BITs. It is consistent with prior evidence and also shows that the treatment effect is not temporary. We provide another placebo test using an alternative estimator recently suggested by Callaway and Sant'Anna (2021) in Appendix C. The results are consistent with Fig. 3.

Placebo effect and persistence of treatment. The plot shows the point estimates of the Wald TC estimator for the 6 quarters leading up and 6 quarter lagging the BIT termination. The dashed lines are the 95 percent confidence intervals, which are clustered by FIHC and calculated with bootstrap based on 1,000 repetitions

6.2 Exclusion of ambiguous termination cases

Moreover, the decision to keep some ambiguous cases and exclude others from our sample could potentially influence our results. Previous research on the determinates of FDI excludes very small counties because they often represent outliers with non-typical investment patterns (one example is tax havens). Another ambiguous case is the United Arab Emirates, which is the only country that ratified a new BIT between 2013 and 2019. Japan and Singapore technically do not have a BIT but only a treaty with investment provisions (TIP) in force. Philippines and Singapore are the only countries in the sample, which still have the BIT not terminated even if it has been technically eligible for unilateral termination.

Another concern is that Mauritius and Singapore, by far the two largest source countries for FDI to India (together almost 45 percent of all inflows), both had double taxation (DT) amendments in the second quarter of the year 2017.Footnote 25 DT agreements are important reasons why investors do channel their investment to India through these countries.

While all BITs with India include ISDS, full protection and security and expropriation clauses, some leave out other properties, which arguably make for a strong BIT. These include national treatment, Most Favored Nation (MFN) and Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET) clauses. We identified these weaker BITs for Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Turkey, Taiwan, Lithuania, and Uruguay. In addition, we see some variation in the strength of the ISDS provisions of Indian BITs. Weaker ISDS BITs exclude some policy areas (e.g. Japan, Singapore, Korea and Mozambique) or impose limitations on ISDS provisions (e.g. Slovakia). The argument is that if BITs and BIT provisions differ in scope, the estimates on the treatment might be contaminated by the strength of the BIT provisions and not the fact that they are kept or terminated.

We therefore, one at a time, exclude all these cases from the sample and report the results of the baseline estimates and finally exclude them all at once. The results are reported in Table 8. They are stable with the expected sign and almost all of them are significant below the 0.05. Hence, none of these decisions about the composition of the sample does change the baseline findings.Footnote 26

7 How do BIT terminations affect FDI?

In the following section, we further explore how BIT terminations actually do matter for FDI inflows in India. For this purpose, we test if BIT terminations act as a signal to the untreated FIHC and how the quality of domestic institutions does affect the impact of BIT terminations on FDI flows. Moreover, we use firm-level data to explore if different types of investments are affected in different ways and if foreign investors have rerouted their investments via other countries after experiencing BIT terminations.

7.1 Do all foreign investors react to BIT terminations? (Anti-investor sentiment argument)

In the baseline estimates, we established a significant negative effect of BIT terminations on FDI flows in the quarters following the BIT terminations. This is evidence that the instantaneous change in investor protection is likely to be an important channel. Another possible channel is the signal of BIT terminations to FIHCs in general. An explanation is that BIT terminations signal a shift in investor-friendliness attitude of the host country.

Several empirical articles explored the legal and signaling channel and find evidence pointing in different directions (Dixon & Haslam, 2016; Gallagher & Birch, 2009; Kerner, 2009; Neumayer & Spess, 2005). If BIT terminations indicate anti-investor sentiment to all foreign investors, at some point the overall FDI inflows should decline while BIT terminations accumulate.

If BIT terminations send out a signal to all investors, they should have significant effects on untreated groups. If the legal protection is the exclusive channel, the accumulation of BIT terminations in India should not affect the FDI behavior of the untreated groups.

We, therefore, exclude all ‘timing’ groups for the whole timespan and estimate the effect of cumulative BIT terminations on the ‘always’ and ‘never’ BIT groups. Table 9 shows that there is no direct effect of BIT terminations on FDI inflows in the untreated groups. The results do not change if we allow for different effects of cumulative BIT terminations for the ‘never’ or ‘always’ group.

Adding cumulative BIT termination along with the BIT termination dummy to the sample restricted to only the ‘timing’ groups, however, shows the expected negative sign for terminations, and a weak significant effect of cumulative terminations on FDI. Adding the interaction of the BIT termination dummy along with cumulative terminations variables reveals a negative interaction effect in column 5, which indicates that the cumulative terminations of BITs augment the effect of the contemporary BIT terminations. An interpretation is that BIT termination of the ‘early’ groups sends out a negative signal to the ‘late’ termination groups while it appears not to transcend to the untreated groups. This is also consistent with the results of the placebo tests, which have shown that investors have not adjusted their behavior before the BIT of their home country with India has been terminated.

7.2 BIT termination and domestic institutions

The absence of finding direct effects of BIT ratifications has pointed past studies to alternative explanations. Some claim that BITs substitute weak domestic institutions (Busse et al., 2010) while others do not find conclusive evidence on this relationship (Neumayer & Spess, 2005; Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2011). Most agree that investigating home-host country differences in institutional features is a viable perspective to understand the role of BITs for FDI activity. The reason is that BITs can substitute weak domestic legal institutions. Without a BIT, the security of property rights of new investments relies mainly on the quality of the host country domestic institutions.

The existing studies investigate the effect of BIT ratifications for countries conditional on varying levels of political constraints and risk, and economic development. We focus on the quality of the legal institutions of FIHCs compared to India. The rationale behind our perspective is that BITs contain wide-ranging investor rights and enforcement procedures for investors, and with BIT terminations new investors lose these safeguards and have to rely on the quality of domestic legal institutions. We expect that if foreign investors observe a large difference between the quality of their home countries’ legal institutions and legal institutions in India, the reduction of FDI inflows is likely much larger compared to FIHC with a similar quality of legal institutions as India.

The World Bank DB indicators assess the quality of formal bureaucratic and judicial processes exclusively for domestic firms, which cannot rely on the additional safeguards from BITs. We use the time and cost of enforcement of private contracts, the duration of judicial trials until the final judgment, and the time to enforcement of the judgment and interact them with the treatment variable. We obtain this data for 116 out of 138 FIHCs in our baseline sample from the DB historical dataset. The data reveals that most FIHCs have more effective judiciary systems and enforcement mechanisms relative to India. The domestic business environment of India is common to all investors countries and is absorbed by the quarterly time dummies.

The results in Table 10 and the plots in Fig. 4 show that FIHCs with similarly long durations of contract enforcement and court trials as in India do not significantly divert FDI activity in response to BIT terminations. This is consistent with the notion that investors with efficient home-country business environments value the reliable and relatively efficient international arbitration procedures for the protection of their rights more than investors from countries with weak legal institutions. Investors form countries with similar challenges are more familiar with them (Azemar et al., 2012; Chang & Chen, 2021) and likely more positive about being able to navigate them even in absence of BIT protection. Taking a closer look at the results, we uncover that the length of domestic trials and not the enforcement of judgments appears to be the most important dimension. This is consistent with our predictions because ISDS claims are heard and decided in international arbitration courts, while after the decision, the awarded claims have to be enforced by domestic courts. These results make sense because BITs only affect the efficiency of how investors are getting a decision on their claims and do not fundamentally alter the way how fast the decisions are enforced.

7.3 Heterogeneity of investments: Firm-level data

Our main data source (DPIIT) does provide FDI inflows for many FIHCs, but it does not reveal how different types of investments were affected by BIT terminations? Exploring this question requires a different data source. To this end, we use firm-level data to further investigate the impact of BIT terminations and in doing so also challenge our baseline results by using an alternative data source.

We obtained the data by accessing the Orbis Crossborder Investment database of Bureau van Dijk and downloaded all equity investments conducted by foreign investors in India (downloaded on September 25, 2021). The database contains information on the date of completion of firms’ projects and deals, their location, and financial information of the investing firms from 2013 onwards. The data allows us to assign BITs and the exact timing (completion dates) of the investments to BIT terminations. An additional advantage besides the ability to distinguish between different types of investment is that the use of an alternative data source enables us to challenge our baseline results. We do not expect that the errors and incompleteness of the Orbis data do exactly match the omissions and misclassifications of the DTIIP data.Footnote 27 The reason is that Orbis Crossborder Investment follows a different search strategy, relies on various different sources and verifies projects and deals with additional information from news and company pages. The substantially lower number of available FIHCs in the Orbis data, however, suggests that there are also omissions and limitations to this data. Using two admittedly imperfect data sources, should still enable us to learn more about the effect of BIT terminations on different types of investments and to challenge our main results with an additional (firm-level) data source.

We follow others by aggregating firm-level FDI data (e.g. Egger & Merlo, Head & Ries, 2008; Rossi & Volpin, 2004) on country-level.Footnote 28 In our case, we aggregate deals (mostly e.g. M&As, buyouts) and projects (including new projects, expansions, and colocations) conducted by foreign investors to India. We rely on the completion dates of the deals and projects provided by Orbis Cross-Border to arrange the data by FIHC and year-quarter. In doing so, we identify 943 deals from 43 and 2,894 projects from 62 FIHCs. While information on the timing of the completion of projects and deals is delivered very consistently throughout the dataset, information on the actual value of the deals and projects shows lots of missing values. We, therefore, use counts of projects and deals completed of i-th investor in t-th year-quarter to India including again FIHC and year-quarter time dummies and control variables. After removing the same ambiguous cases of FIHC as for the baseline estimates, the total number of deals and projects and summary statistics ae displayed in Table 1.

Table 11 shows the results of the BIT terminations on total investment (all projects and deals), and on deals and projects separately. While the coefficients show the expected negative sign throughout these specifications, the results for total investments and projects are insignificant. The results for deals, however, show considerably higher negative and highly significant effects of BIT terminations.

Based on these results from our firm-level data source, the negative effect of BIT termination on FDI inflows to India appears to be largely driven by significantly fewer deals conducted by investors after the BIT of their home country with India has been effectively terminated.

Another (complementary) explanation is that revoking or rerouting of M&As and buyouts in response to BIT terminations might be feasible at lower costs, while new projects often involve long-term planning and costly upfront activity and are therefore costlier to be diverted close to completion. This is consistent with our finding that foreign investors do not tend to discontinue new projects in response to BIT terminations compared to FIHCs with no change in BIT status. Moreover, the category projects also include project expansions and colocations, which we do not expect to be affected by BIT terminations if they are based on existing projects. The reason is that due to the sunset clause, these projects would still be eligible to access to ISDS even after BIT terminations. Finally, another aspect for the diversion argument of deals is that these investment types have been more strictly regulated in India compared to Greenfield investments (e.g. new projects) (Rao et al., 2018).

To check, whether the results are affected by the sample composition (e.g. due to the availability of fewer FIHCs in the firm-level data set), we re-estimate the baseline model with the exact same composition of FIHCs as our original DPIIT data set. The results are consistent with our earlier findings and presented in columns 7 and 8.

Although the data sources are far from perfect, the fact that these two different, independently collected data sources, both detect a sharp decline in investment activity in response to BIT termination, makes us confident that our results are not an artifact of the choice of a specific dataset.

7.4 Treaty shopping and rerouting as a possible channel

Although in total, FDI inflows declined after 2016, this does not necessarily say that investors from FIHCs with BIT terminations are not interested in India anymore.Footnote 29 According to our baseline results, FDI inflows to countries with BIT terminations had declined on average by over 30 percent compared to FIHCs without BIT terminations. The overall decline of FDI inflows to India in 2017 (the year with the most BIT terminations) amounts to only about 9 percent (from 44 to 40 billion US-$, UNCTAD, 2018). A possible explanation for the fact that Indian FDI inflows overall had not decreased further is rerouting of FDI and a practice called treaty or forum shopping (e.g. Baumgartner, 2016). The logic of this practice is that in order to direct their investment to a specific host country, foreign investors establish (often smaller) subsidiaries in countries with ratified or stronger BITs (e.g. Georgallis et al., 2021). The presence of this behavior would strengthen the argument, that investors really are distracted by the absence of BIT-based investor protection and not ant-investor sentiment. A simple test is to investigate if aggregate FDI inflows to India from FIHCs with BIT terminations had plummeted in a year with many BIT terminations (e.g. 2017) while at the same time FIHCs, which maintained their ratified BITs (‘always group’) over the whole time period of the study, had increased their investment activity in the same year. Figure 5 shows that rerouting practices of FDI into India were a highly likely response to the large-scale BIT terminations of the year 2017.

The argument for treaty shopping is also supported when looking at the firm-level data. Large companies like Procter & Gamble (via the Netherlands) or Amazon (via Mauritius) apparently had strategically placed subsidiaries to invest in India because the United States does not have a BIT with India. Although our data does not directly allow us to track relocation of firms in response to BIT terminations, the patterns in the aggregate data and the presence of such subsidiaries in locations suspicious for rerouting activity indicate that a substantial fraction of the revoked FDI inflows in response to BIT terminations had been rerouted via countries with ratified BITs.

Summing up, our earlier findings paired with this evidence that investors obviously respond to BIT termination with rerouting, lead us to the conclusion that investors react to the disruption in legal investor protection (e.g. sudden absence of ISDS provision) and do not divert investments in anticipation of anti-investor sentiment.

8 Conclusion

Identification of the impact of BIT ratification on FDI is notoriously difficult because the relationship is endogenous and the adjustment of investors’ behavior to new investor protection terms is difficult to predict. In contrast, our study of India provides a new angle, which allows us to identify the impact of BITs by shifting the perspective to BIT termination. The main advantage of this setup is that we are able to show that BIT terminations are plausibly exogenous to India and FIHC-specific characteristics and that terminations do represent sharp breaks with existing BIT-based investor protection. This enables us to use quasi-experimental methods to identify the impact of BITs on FDI. Moreover, the unique setting of BIT terminations in India allows us to study multiple comparison groups within one very large country with multiple data sources.

Based on a sample of 138 FIHCs over 26 year-quarter periods, we find a consistent negative effect of BIT terminations on FDI inflows. We estimate two-way fixed DD for multiple groups and periods and compare the results with the findings of two relatively new DD estimators that are capable of estimating the (average) treatment effect in presence of heterogeneous timing. The results of all three approaches are consistent and the effect sizes, in general, are substantial and significant with drops of more than 30 percent in FDI inflows for FIHC with BIT terminations compared to FIHC with no change in BIT status. We include several further tests of the identifying assumptions, demonstrate that the results are not driven by sample composition, the choice of the data set, and end with an assessment of potential channels explaining how BIT terminations do affect FDI inflows.

Based on these robustness checks, we can specify that mainly deals such as M&As, and buyouts were diverted in response to BIT terminations and that many investors likely (strategically) rerouted their investments via subsidiaries to countries with a ratified BITs in place. Moreover, differences in the effectiveness of the domestic court system (rather than the bias of the court system) between the FIHC and India are important factors to explain the influence of BIT terminations on FDI inflows. In case of India, foreign investors which are used to lengthy trials in their home country do not show significant changes in their behavior in response to BIT termination. Investors with reliable court systems at home, however, appear to particularly value the option of dispute settlement via BIT-based ISDS procedures.

These results provide several new insights in how foreign investors do relate to BITs. We show that foreign investors care about investor protection by BITs. This is further indicated by the fact that FDI inflows attributed to FIHCs declined after their respective BIT has been effectively terminated. In contrast, the announcement of BIT terminations or the terminations of BITs of other FIHCs, in general, have not significantly changed investment activity of foreign investors. This suggests that it is the legal instrument BIT with investor protection, which does matter to foreign investors and not anti-investor sentiment signaled by BIT terminations. It is also consistent with findings from our further analysis that foreign investors do not necessarily abandon the idea to invest in India after BIT terminations but tend to strategically reroute their investments through countries, which still maintain a ratified BIT. Finally, we find that mainly deals like M&As and buyouts are significantly affected by BIT terminations, while firms obviously do not significantly reduce new projects in response to BIT terminations compared to FIHCs with no BIT terminations. A reason could be that new projects oftentimes require longer planning phases and might therefore be less feasible for rerouting compared to deals.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Notes

Between June 1959 and 2019, 3,291 International Investment Agreements (IIAs) have been signed and more than 80 percent of them have been ratified. They are valid treaties, which protect investors from violation of investor rights by host country public officials. Of more than 300 terminations, 177 ended with unilateral terminations.

The data on signing, ratification and termination is recorded in the UNCTAD investment policy hub database.

A simple search for ‘Bilateral Investment Treaties’ results in 30,500 entries on google scholar and 779 articles in academic journals on SCOPUS (accessed 10.4.2022).

Some find positive effects of BITs on aggregate FDI (Busse et al., 2010; Büthe & Milner, 2009; Egger & Merlo, 2007; Egger & Pfaffermayr, 2004; Haftel, 2010; Kerner & Lawrence, 2014; Neumayer & Spess, 2005; Salacuse & Sullivan, 2005), while others find no empirical evidence in support of this relationship (Aisbett, 2009; Blonigen & Piger, 2014; Hallward-Driemeier, 2003; Tobin & Rose-Ackerman, 2005; Yackee, 2008).

Throughout the paper foreign investor activities or FDI refer to the aggregates of investment activities of foreign firms from the same home country.

ISDS procedures enable foreign investors to file claims against their host state at international arbitration courts. In doing so, investors can get rulings on alleged breaches of their rights without any involvement of domestic courts.

See UNCTAD Investment Policy Hub. Due to sample restrictions, we could not add four more terminations because they happened after our sample of bilateral FDI ends in 2019.

The case ‘White Industries Australia Limited v. The Republic of India’, has been quoted in reference to the decision of India to review its BITs (see: Press release of the Indian Ministry of Commerce & Industry (6 May 2013). https://pib.gov.in/newsite/erelease.aspx?relid=55875). The cases concluded in 2011 and quoted ‘judicial delays’ as reason why it was decided against India. The award required India to pay AUD 98,12,077 as compensation to the Australian firm.

One key element is that investors should consult domestic Indian courts before they file ISDS claims. Press Information Bureau Government of India Ministry of Finance, Model Text for the Indian Bilateral Investment Treaty, 16. December 2015. https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=133412.

The only newly ratified BIT with the United Arab Emirates (ARE) in August of 2014 has used the old model BIT.

The major importance of ISDS provisions to investor has also been detected in a recent managerial survey, which indicates that ISDS is strongly preferred over most other available litigation methods and treaties without ISDS would be substantially less attractive to the investors (QMUL-CCIAG, 2020: Chart 1 & 3).

There are only two exceptions of BIT, which do not include modalities of unilateral termination. The first is Korea, which is excluded from our sample because it has one BIT terminated and at the same time a complementary TIP in force. The second is United Arab Emirates, which had been signed and ratified the BIT in 2014.

The change of the expiration date could have been circumvented by consensual termination, but this has not been invoked in case of India.

More precisely, they refer to the problems of the two-way fixed effects estimator.

We admit that that arguably weaker BITs or ISDS provisions could affect our results and thus exclude them in further robustness checks (see Table 7 columns 10–14).

The end date is the most recent data issued by the time we conducted our analysis.

The inflows are denominated in current US-Dollars, which we seasonally and quarterly adjust with the implicit price deflator (1st quarter 2012 = 100) from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

We do not count terminations of BITs, which have never been ratified. This reduces the number of terminations from 68 terminations to 44 BITs. Table 1 summarize the composition of these groups and the countries excluded fromthe sample for these reasons.

After the termination of the BIT in 2017, Belarus has been the first country, which signed a new BIT in 2018. India also signed a TIP with ASEAN in 2014. Both treaties have not been ratified yet. Finland, Island, Mexico, Saudi-Arabia and Turkey BIT were unilaterally terminated after our sample ends.

We have to exclude the United Arab Emirates from the sample because the Bacon estimators allow only for switching into treatment and not vice versa. United Arab Emirates ratified a BIT in 2014 and therefore has to be excluded from the sample.

The coefficients are consistent and significant although due to the 2-step procedure, the standard errors are likely biased and have to be interpreted carefully.

The choice of six quarters appears as a reasonable time window to us because it exceeds the minimum notification period for BIT termination, which is one year. In further robustness checks, we increase and decreased the pre- and post-treatment phases and found that the results are not affected by the length of the time window. These results are not reported but are available upon request from the authors.

The amendment made it harder for investors to save taxes. Mauritius was more severely affected because it now requires investors to have a significant presence in the country to be able to transfer capital gains tax-free.

E.g. Orbis cross-border follows a different search strategy, relies on various different sources and verifies projects, and deals with additional information from news and company pages.

In a slight deviation of this analysis, we repeat the analysis using the investment data disaggregated along with firm-fixed effects. The results remained consistent. The results are not reported but are available upon request.

This likely strategic consideration has been pointed out by two anonymous reviewers. We are very grateful to them for this insight. This helped us with understanding the mechanisms behind BIT termination and our results and substantially improved our paper.

References

Ahir, H., Bloom, N., & Furceri, D. (2018). The World Uncertainty Index.

Aisbett, E. (2009). Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: correlation versus causation. In K. P. Sauvant & L. E. Sachs (Eds.), The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows (pp. 395–435). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aisbett, E., Busse, M., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2018). Bilateral investment treaties as deterrents of host-country discretion: The impact of investor-state disputes on foreign direct investment in developing countries. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 154(1), 119–155.

Autor, D. H. (2003). Outsourcing at will: The contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. Journal of Labor Economics, 21(1), 1–42.

Azemar, C., Darby, J., Desbordes, R., & Wooton, I. (2012). Market familiarity and the location of South and North MNEs. Economics & Politics, 24(3), 307–345.

Baumgartner, J. (2016). Treaty shopping in international investment law. Oxford University Press.

Berger, A., Busse, M., Nunnenkamp, P., & Roy, M. (2011). More stringent BITs, less ambiguous effects on FDI? Not a bit! Economics Letters, 112(3), 270–272.

Berger, A., Busse, M., Nunnenkamp, P., & Roy, M. (2013). Do trade and investment agreements lead to more FDI? Accounting for key provisions inside the black box. International Economics & Economic Policy, 10(2), 247–275.

Bergstrand, J. H., & Egger, P. (2013). What determines BITs? Journal of International Economics, 90(1), 107–122.

Bertrand, M., Duflo, E., & Mullainathan, S. (2004). How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 249–275.

Besley, T., & Burgess, R. (2004). Can labor regulation hinder economic performance? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 91–134.

Bilir, L. K., Chor, D., & Manova, K. (2019). Host-country financial development and multinational activity. European Economic Review, 115, 192–220.

Blonigen, B. A., & Piger, J. (2014). Determinants of foreign direct investment. Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(3), 775–812.

Busse, M., Koniger, J., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2010). FDI promotion through bilateral investment treaties: More than a bit? Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 146(1), 147–177.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2009). Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: A political analysis. In K. P. Sauvant & L. E. Sachs (Eds.), The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: Bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows (pp. 171–224). Oxford University Press.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2013). Foreign direct investment and institutional diversity in trade agreements: credibility, commitment, and economic flows in the developing world, 1971–2007. World Politics, 66(1), 88–122.

Cai, X., Lu, Y., Wu, M., & Yu, L. (2016). Does environmental regulation drive away inbound foreign direct investment? Evidence from a Quasi-natural experiment in China. Journal of Development Economics, 123, 73–85.

Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. C. (2021). Difference-in-Differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230.

Calvert, J. (2018). Constructing investor rights? Why some states (Fail to) terminate bilateral investment treaties. Review of International Political Economy, 25(1), 75–97.