Abstract

While many issue areas of global governance have witnessed the proliferation of evermore overlapping institutions, the topologies underlying regime complexes differ from strongly centralised, to rather decentralised institutional structures. This paper contributes to a better understanding of this phenomenon in two ways. First, it proposes a conceptualisation of institutional topologies that takes a social network perspective. Second, building on economic good theories, the paper complements the existing arguments about policy area competition claiming that they overlooked the important role of the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits. This policy specific variable shapes an institutional complex’s propensity for competition which, in turn, spurs the (de)centralisation of institutional complexes. Two structured comparisons provide empirical support for this argument: comparing the propensities for competition and network structures underlying the institutional complexes of TA and intellectual property protection, I show that despite their many similarities, fundamental differences regarding the excludability of institutional benefits co-vary with fundamentally different institutional configurations. I complement these findings with qualitative case studies of institutionalisation processes in both policy fields rendering further empirical support for the theory’s underlying causal claim.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global governance has witnessed the proliferation of ever more, sometimes overlapping international institutions. This has spurred the development of dense and oftentimes conflictual governance systems producing what scholars refer to as ‘regime complexes’ (Benvenisti and Downs 2007; Biermann et al. 2009; Alter and Meunier 2009; Hofmann 2011, 2019; Keohane and Victor 2011; Orsini et al. 2013; Urpelainen and van de Graaf 2015). Regime complexity has affected state behaviour as they are incentivised to shift their activities away from hitherto ‘core institutions’ towards alternative intergovernmental arrangements leading to a situation Morse and Keohane (2014) describe as ‘contested multilateralism’. However, complexity is also accompanied by the evolution of diverse forms of interaction among multilateral institutions themselves: they coordinate policies, defer, and refer to each other or even conflict over jurisdictions (Biermann 2008; Gehring and Faude 2014; Harsch 2015; Pratt 2018; Hofmann 2019).

Still, this underlying, implicit topology of institutional complexes varies greatly across policy areas. In some areas like financial stability, the lion’s share of everyday policy cooperation is shaped by a single institution, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with alternative and more regional institutions like the Chiang Mai Initiative (CMI) or the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) operating in its shadow, linking their institutional rules closely to those of the IMF (Schwarzer 2015). In other policy fields like development aid, institutional structures appear to be different. Here, the World Bank (WB) finds itself increasingly confronted with competition for projects by these alternative institutions (Humphrey 2014). It thus seems that, in this policy area, decentralised institutional structures have evolved. What explains this apparent (de)centralisation of institutional structures across policy fields?

IR scholarship on regime complexes has so far tended to focus on the consequences of this increase in complexity. While some authors argue that the growing number of institutions governing the same issue area leads to improved cooperation and the division of labour among them which helps to increase the benefits of cooperation (Kellow 2012; Gehring and Faude 2014; Pratt 2018) others suggest that the increasing number of institutions sharing similar jurisdictions leads to regulatory and legal uncertainty, higher transaction costs and growing inequality among states as it helps powerful states to increase their influence over outcomes (Raustiala and Victor 2004; Helfer 2009; Benvenisti and Downs 2007; Henning 2019; Biermann et al. 2010; Johnson and Urpelainen 2012). Both strands in the literature share their analytical focus on the consequences of varying institutional structures. Studies theorising and assessing conditions for the evolution of (de)centralised complexes have remained scarce.

Following the very recent call by Henning and Pratt (2020: 2) to ‘strengthen the foundation for comparative analysis of regime complexes and improve cumulation across studies’, this paper proposes to (re-)shift the focus from assessing the consequences of complexity towards their empirical manifestations and causes. Taking Lipscy’s (2015, 2017) theory of policy area competition and institutional change as a starting point, the paper refines and complements his concept of institutional competition by focusing on an important market characteristic of policy fields which has so far been overlooked by the literature on regime complexes. Drawing on theories on economic good characteristics of institutional cooperation (Cornes and Sandler 1996; Mattli 1999; Kaul et al. 1999; 2003; Kölliker 2001), I emphasise the important role of the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits in shaping policy area competition and, thus, the evolution of (de)centralised institutional topologies. More precisely, the paper claims that institutional competition is not only a consequence of network effects and barriers to entry (Lipscy 2015, 2017) but is also shaped by the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits. Differentiating between policy areas in which institutions are set up to provide club goods which can be enjoyed by member states exclusively, and policy fields where cooperation is established to provide public goods from which non-member states cannot be excluded, I claim that policy fields may exhibit fundamentally varying incentives for states to engage in the creation of overlapping institutions. The excludability of institutional benefits incentivises states to engage in regime shifting, forum shopping or alternative regime creation, thereby reinforcing institutional competition and spurring the evolution of decentralised institutional topologies. If, however, institutional cooperation provides public goods from which non-participants cannot be excluded effectively, institutional competition is low, creating incentives for states to foster inclusive and rather universal institutions while refraining from competitive institution-building, regime shifting or forum shopping.

The paper will proceed as follows. The next section introduces a theory of institutional topologies. It introduces a network approach which captures interactions among both institutions and member states allowing to map institutional topologies descriptively across policy areas. The section further discusses the main conceptual differences to existing efforts to conceptualise regime complexity. In the ensuing empirical section, I apply my framework by analysing institutional topologies underlying the policy fields of tax avoidance (TA) and intellectual property rights (IPRs). Following the logic of a most similar system, I show that while both policy fields are relatively similar, inter alia when it comes to network effects and barriers to entry, they exhibit significant differences when it comes to the excludability of institutional benefits. While in the policy field of TA, non-participating states cannot be prevented from free riding on the positive effects of cooperative efforts by institutional members, in the policy field of IPRs, non-participating states are seriously threatened by the exclusion from essential institutional benefits like access to trade networks and foreign direct investment. While the propensity for competition is therefore low in the complex of TA, the policy field of IPRs exhibits a comparatively strong degree of institutional competition. By mapping inter- institutional reference and membership networks underlying both issue areas, I show that both policy field’s’ institutional topologies vary greatly. Going beyond this mere co-variation analysis, in a final empirical section of this paper, I provide two case studies of institutionalisation processes in both policy fields to further demonstrate the plausibility of my argument.

Conceptualising and theorising institutional topologies in regime complexes

I define the relational structure among institutions set up to govern the same policy field as the institutional topology of a regime complex. While some complexes are marked by high degrees of centrality, others exhibit decentralised topologies. I argue that an institution’s relative position within its complex is a function of its recognition by other institutions and states (Sending 2017; Lake 2009, 2011; Zürn et al. 2012; Daßler et al. 2022; Kruck et al. 2022; Heinkelmann-Wild et al. 2021). Central positions within institutional complexes allow actors to exercise authority by directly or indirectly constraining others (Zürn et al. 2012: 70; Hooghe and Marks 2015). Only if international institutions are recognised by states and by other institutions claiming to govern the same policy issue, they can constrain, initiate, or encourage political actions by states on the respective issue. An international institution’s centrality in a certain complex thus hinges on its success in ‘claim[ing] the right to perform regulatory functions like the formulation of rules and rule monitoring or enforcement’ (Zürn et al. 2012: 70) within their policy areas.

To measure the topology of institutional complexes, I propose to think of them as social networks structured by the interaction of its constitutive actors, institutions, and states. Taking a social network perspective allows for the ‘fine-grained conceptualization and measurement of structures’ (Hafner-Burton et al. 2009: 561) and thus, to draw an abstract picture of a complex’s underlying cooperative activities which can be compared across policy fields, even if they differ greatly regarding characteristics of their underlying institutions or the number and characteristics of states involved. Its ability to analyse descriptively the degree of (de)centralisation of institutional cooperation across a potentially large set of completely different policy fields makes the network perspective complementary to other quantitative methods analysing regime complexity systematically (Haftel and Lenz 2021; Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn 2020; Gholiagha et al. 2020). These sophisticated approaches allow for a fine-grained quantification of different qualities of inter-institutional structures, e.g. the degree of policy and membership overlap (Haftel and Lenz 2021) or dyadic conflicts among a complex’s constitutive institutions (Kreuder-Sonnen and Zürn 2020; Gholiagha et al. 2020). While both approaches zoom-in on the micro level of dyadic institutional overlap and conflict thereby providing important insights into the quality of complexity, the network perspective provides a structural perspective focusing on the degree of (de)centralisation of institutional cooperation within different policy fields.

States—understood as bounded rational and uniform actors – seek cooperation on issues where they expect the cooperative outcome to be beneficial and representing a mutually preferable equilibrium (Oye 1985; Abbott and Snidal 1998; Koremenos et al. 2001). Scholars have stressed that external conditions like the situational dependency structure (Copelovitch and Putnam 2014; Jupille et al. 2013) or state interests and their relative power are important variables that shape the design of institutions (Urpelainen and van de Graaf 2015; Johnson and Urpelainen 2012). While I agree with these theories about the causal relevance of interests and power when it comes to the evolution of institutional configurations, I argue that they underestimate the policy area specific propensity for competition and its role as a moderator constraining or enabling the proliferation of overlapping institutions.

Taking Lipscy’s (2015, 2017) theory of institutional change as a starting point, this paper argues that the concept of policy area competition not only helps to better grasp the conditions for intra-institutional reform, but also helps to better understand change or resilience in inter-institutional topologies. I further refine and complement Lipscy’s theory by claiming that it has overlooked an important issue area characteristic shaping the propensity for institutional competition, i.e. the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits.

In his seminal contributions, Lipscy (2015, 2017) argues that there are two variables shaping a policy area’s propensity for institutional competition. The first policy area characteristic is the presence or absence of network effects, ‘which arise when the marginal utility of joining an activity increases with the total number of participating states’ (Lispcy 2017: 28). High network effects are considered to weaken institutional competition, as they incentivise states to corporate via large- scale and rather universalistic institutions. The second policy area characteristic are barriers to entry. These ‘hindrances to alternative forms of cooperation’ (Lipscy 2017: 28) increase the political and material costs for states to set up alternative institutions. Thus, the higher barriers to entry, the more costly and hence less attractive it is for states to pursue institutional outside options which results in low propensities for institutional competition. While I agree with the causal relevance of both variables, drawing on economic theories about good characteristics, I argue that there is a third ‘market characteristic’ of issue areas, the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits, which needs to be considered to fully grasp the competitive structure underlying international regime complexes.

Economists as well as political scientists have produced a burgeoning literature on how the type of good provided by economic or state actors affects incentives for private as well as political actors to engage in its supply (Clarke 1971; Ostrom 1990; Cornes and Sandler 1996). This literature differentiates whether a good is (non-)rivalrous, and (non-)excludable.Footnote 1 While the first, internal dimension addresses potential distributional conflicts over the good among institutional members due to its (in)finite supply, the second, external dimension focuses on whether actors not involved in the creation of the good can be effectively excluded from its positive effects or not. I argue that, within international regime complexes, it is particularly the latter, external dimension of an institutional good that strongly affects a policy field’s propensity for institutional competition. The attractiveness of outside options depends on whether there are positive externalities for non-participating states or, on the contrary, benefits can exclusively be enjoyed by institutional members. In the latter case, incentives to join the existing institutions or to create completely new ones are high. In the case of non-excludable institutional benefits, on the contrary, they are absent. Thus, it matters whether institutional cooperation is associated with benefits resembling a club good (Mattli 1999: 59‒64), which can be enjoyed exclusively by member states, or whether institutional cooperation is associated with benefits resembling a public good, where non-participating states equally enjoy benefits stemming from cooperation by others (Snidal 1979: 539‒44).

Issue areas with non-excludable institutional benefits (public good provision): if policy issues require that institutions are set up to provide public goods, comparatively low institutional competition can be expected, favoruing the evolution of centralised institutional topologies. The main reason is the free rider problem (Runge 1984: 156; Carraro and Siniscalco 1998: 2; Fischbacher and Gachter 2010). Once public good institutions are established, incentives to create alternative institutions decrease sharply.Footnote 2 Non-participating states benefit from the public good provision by others without having to bear any costs by themselves. Moreover, in issue areas where institutions provide public goods, non-members face positive externalities through the cooperation of others. Thereby, the pre-existence of a public good institution creates disincentives for outsider states to engage in the creation of institutional alternative (Hofmann 2011). For instance, if a group of states decides to set up an environmental agreement in which they obligate themselves to reduce their carbon dioxide emissions, the positive effects on global climate are not restricted to member states, but equally beneficial for those states who refrain from cooperation. Thus, within issue areas where the provision of non-excludable goods is central to institutional cooperation, states refraining from cooperation face positive externalities arising through the cooperation by others (Kölliker 2001: 130; Mattli 1999: 59‒64). Here, positive external effects for outsiders are significantly higher than the internal costs of participation (Kölliker 2001). This, in turn, significantly reduces the attractiveness of institutional outside options. Even more, the non-excludability of cooperative benefits creates strong incentives for members of the existing public good institutions to opt for a strategy of ‘buying non-members in’, thereby unintendedly further weakening institutional competition and reinforcing centripetal tendencies within a regime complex. As institutional members are interested in the (re)distribution of costs and the expansion of the institution’s underlying rules and norms, they have to offer non-participants benefits in exchange for their participation. To ensure their participation, institutional outsiders need to be co-opted e.g. by ‘trading institutional privileges for institutional support’ (Kruck and Zangl 2019: 321). Such privileges can entail the provision of soft and non-binding arrangements which allow non-members access to institutional resources without requiring legally binding commitments associated with sovereignty costs (Abbott and Snidal 2000). Consequently, the attractiveness of institutional outside options is low in issue areas where institutions provide non-excludable goods. States face no incentives to engage in competitive regime creation or forum shopping, institutional competition remains weak which, in turn, creates centripetal rather than centrifugal effects on the institutional complex’s underlying topology.

Issue areas with excludable institutional benefits (club good provision): if policy issues allow states to set-up institutions providing club goods where non-participants can effectively be excluded from institutional benefits, comparatively high institutional competition can be expected, favoruing the evolution of decentralised institutional topologies. Here free riding on the provision of non-excludable goods by others is not possible. Moreover, as compared to issue areas where public goods are central to institutional cooperation, there are no positive externalities for non-members. Positive internal effects for members are significantly higher than positive external effects for outsiders (Kölliker 2001: 134–38). Quite the opposite, institutional clubs are oftentimes associated with negative externalities for nonmembers. For instance, if a group of states decides to establish a military alliance with reciprocal security guarantees, the good provided by the respective institution can be enjoyed exclusively by member states (Bernauer 1995; Buchanan 1965: 2; Cornes and Sandler 1996: 34; Sandler and Tschirhart 1997: 337). Moreover, the pre-existence of such an institutional club often comes with negative effects for non-participants. The establishment of exclusive security institutions can lead to increasing uncertainty among non- members who view the exclusive institution as a potential threat, provoking them to engage in counter-institutionalisation. Military alliance states are not participating. For non-participants to enjoy the benefits provided by security institutions, it is necessary to either join the existing arrangements or to create their own institutional club. This, I argue, creates centrifugal effects in a regime complex’s underlying topology. In such issue areas, where the threat of exclusion from essential institutional benefits is real, states oftentimes find themselves forced to enter institutional arrangements rules which are not in line with their interests to avoid the negative effects of being excluded from the good provided by the institutional club. For instance, the decision to abstain from a certain free-trade arrangement comes with prohibitively high costs for states as they may find themselves excluded from essential markets, so they eventually agree upon rules harmful to their economic development to avoid these negative effects of exclusion (see in particular Gruber 2001; Murphy 2009; Slapin 2009). Thus, and in contrast to issue areas where institutions provide public goods, excludability allows cooperators to force, rather than having to coopt, the unwilling into institutionalised forms of cooperation. Here, the pre-existence of institutions providing excludable goods alter the preferences of states (Hofmann 2011). For those states forced to join to avoid the negative consequences of exclusion, as well as for those states capable of pursuing independent institutional alternatives, strong incentives arise to create or strengthen institutional alternatives to mitigate the negative effects of the existing club’s unpleasant rules. Engaging in strategies like competitive regime creation, regime shifting (Helfer 2004, 2009) or forum shopping (Busch 2007) become rational strategies. Consequentially, in issue areas marked by the institutional provision of non-excludable goods, centrifugal effects arise on the complex’s institutional topologies.

Synthesising the above considerations, I formulate the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1:

All else equal, within policy areas, where institutionalised cooperation is associated with the provision of excludable goods, the propensity for inter-institutional competition is higher, and institutional topologies are more decentralised.

Hypothesis 2:

All else equal, within policy areas where institutionalised cooperation is associated with the provision of non-excludable goods, the propensity for inter-institutional competition is low and institutional topologies are more centralised.

To probe the plausibility of these claims, the following section provides a structured comparison of two policy fields and their underlying institutional complexes. Most importantly, the analysis seeks to establish the independent effect of the issue area characteristics of (non-)excludable institution goods on the policy field’s propensity for institutional competition. In particular, the analysis probes the claim that institutional competition is not merely a result of network effects and barriers to entry as suggested by Lipscy (2015, 2017) but is also strongly affected by the (non-)excudability of institutional benefits. Therefore, following the logic of most similar system designs, the section begins by highlighting important similarities of the field of TA and IPRs. This allows to further control for important alternative explanations like interest constellations and power configurations. I then turn to my independent variable of interest, the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits. I demonstrate that when it comes to this issue-specific variable, both policy fields differ greatly which translates into significantly different degrees of institutional competition.

The competitive structure of the policy fields of Intellectual Property Rights and Tax Avoidance

The issue areas of TA and IPRs share important characteristics regarding the functional need for cooperation. Within the policy field of TA, states cooperate to harmonise their taxation policies to mitigate incentives for tax evasion which creates incentives for harmful tax competition among states (Eden and Kudrle 2005: 104; Rixen 2011; Hakelberg 2015; Ndikumana 2015). Intergovernmental cooperation on IPRs, on the other hand, seeks to establish rules among states that regulate the protection of immaterial goods (Sell 2017). Thus, in both fields, states bargain about institutional rules addressing the (re)distribution of economic profits. In the field of TA, they negotiate about the rate and jurisdictions of taxes. In the issue area of IPRs, states bargain about the compensation of private entities for the use of their immaterial goods. These similarities of the underlying cooperation problem should, from a rational-institutionalist perspective (Koremenos et al. 2001; Abbott and Snidal 1998; Keohane and Victor 2011; Jupille et al. 2013), translate into comparable institutional configurations in both fields. We should observe that the institutional topology underlying both issue areas provide equally central positions to those institutions offering the most ‘fitting’ design in terms of utility maximisation for states. At least, there should be no profound differences in how institutionalised forms of cooperation are pursued in both policy fields.

Moreover, variation in institutional competition and thus, topologies, cannot be explained by the interests of powerful states alone, as suggested by neorealist arguments (Benvenisti and Downs 2007; Drezner 2009; Ikenberry and Lim 2017). In both issue areas, economically powerful states strive for binding rules to counter the problem of TA through the shifting of capital to tax havens, predominantly situated within economically small states, and the problem of the non-paid use of IP by counterfeiting industries, which are also predominantly situated within economically weaker states. Powerful states like the US, Germany or Japan have traditionally been strong proponents, in both policy areas, of stricter and more binding rules which are in line with their economic interests and have articulated these ambitions within institutions like the OECD or the WTO’s TRIPs agreement. By contrast, in both fields economically weaker states argue for low and flexible regulations. According to them, attracting capital through low tax rates as well as the cheap production and retail of non-licensed products are key to their economic development. However, as I will show in the subsequent section, in both issue areas these similar power structures did not translate into equally centralised patterns of institutional cooperation catering to the interests of these powerful states. The power structure among negotiating states can thus not account for varying institutional topologies across both issue areas.

Furthermore, both policy areas exhibit striking similarities when it comes to barriers to entry and network effects (Lipscy 2015, 2017). To begin with, material and immaterial hurdles to set up institutionalised forms of cooperation in both areas are relatively moderate. First, states do not need vast material or immaterial resources to initiate cooperation on IPRs: due to their intangible nature, there are no significant material hurdles for states to engage in institutionalised cooperation on IPRs (Muzaka 2010: 763; Emmert 1990: 1318). Unlike in e.g. the issue area of financial stability where states require vast financial resources to set up institutions capable of solving balance of payments issues by its members, in the issue area of IPRs, states can engage in cooperation irrespective of their financial resources. Even economically weak countries set up IP institutions to protect traditional and indigenous knowledge or biological or genetic resources (Daßler et al. 2019). Furthermore, virtually every state in the world today runs national or even subnational patent offices where the bureaucratic and legal expertise necessary to engage in intergovernmental cooperation on intellectual property issues exists (WIPO 2019). The same holds for the issue area of TA: just like in the field of IPRs, states do not need to (re)create vast capacities to engage in cooperation on the issue of TA at the international level. Modern corporate income tax policies and the associated bureaucratic and legal expertise, despite some scarce exceptions, have spread across the globe and have also been introduced among low-income countries throughout the last decades (Seelkopf et al. 2016). Moreover, the regular and frequent bilateral exchange of information among governments regarding their taxation policies is well established in most countries, meaning that governments usually are aware of other state’s taxation policies further decreasing the costs of cooperation on TA issues (Dehejia and Genschel 1999: 404).

However, in both issue areas there are also similar challenges regarding enforcement. To effectively implement measures against TA proposed by international institutions, members need to make substantial resources available exclusively devoted to tax enforcement (Slemrod and Wilson 2009: 1262). This implies the need for international legal expertise beyond the existing national capacities that allows enforcement of institutional provisions. The same holds for the policy field of IP protection. To counter the inflow of unlicensed goods, states need specifically trained customs authorities to efficiently identify and confiscate them. Especially for states lacking these well-equipped and trained customs authorities, the major problem will be their ‘failure to get [their][…] laws and international obligations adequately and effectively enforced’ (Massey 2006: 232). The case of the Chinese government’s long-lasting struggle to contain the problem of ‘piracy’ to fulfil their institutional obligations illustrates this. For China, high enforcement costs have been for a long time a significant hurdle for deepening institutional cooperation on IP which they needed in order to gain access to Western markets (Massey 2006). Thus, both issue areas are remarkably similar when it comes to barriers to entrerinstitutionalised forms of cooperation.

Both policy fields are further similar when it comes to network effects. In both cases, the ‘marginal utility of joining an activity’ (Lipscy 2017: 28) does not increase but decreases with the total number of participating states. For tax havens creating large shares of their economic growth by attracting foreign capital through low tax rates, the marginal utility of joining a TA institution decreases with growing numbers of institutional members. For them ‘being a tax haven in a world where every other state is also a tax haven is not very profitable but being the sole tax haven in an otherwise tax haven-free world is potentially very profitable’ (Genschel and Plümper 1997: 637). The more states decide to join a respective tax institution, the lower the incentives for non-participating states to join in. Indeed, the complete abolishment of harmful tax competition is only thinkable in the case of a truly universal institution (Rixen 2011: 204; Dehejiha and Genschel 1999). The same holds for the issue area of IP protection. For states interested in the deregulation of IP, the marginal utility of abstaining increases with growing numbers of cooperators. The demand for non-licensed products sold by their counterfeiting industries increases with more states abolishing their own ‘piracy firms’. This, in turn, may incentivise those states with important counterfeiting industries to abstain from cooperation the more other states decide to oblige themselves to institutionalised rules protecting IPRs. The role of Brazil and India in the dispute surrounding the production and export of generic drugs through compulsory licenses is an excellent example of such an effect. The establishment of the large-scale TRIPS agreement in 1995 prompted many economically weak countries to look for alternatives to the expensive and now patent-protected pharmaceuticals which they desperately needed to tackle the spreading HIV/AIDS epidemic. Both India and Brazil promoted the generic drugs produced under compulsory licenses by their domestic pharmaceutical industry, which led to a significant decrease in prices for HIV/ AIDS drugs in economically weak countries while strengthening their pharmaceutical industries specialised in the production of generic drugs (Coriat 2008: 9; Dauvergne and Farias 2012: 910–11; Grace 2004). Thus, in both issue areas states interested in deregulation rather than institutionalisation benefit from higher numbers of states. In contrast to e.g. the policy field of financial stability, where there are strong network effects present curbing down institutional competition by creating incentives for all states to participate in universal institution (Lipscy 2017: 68‒70), in the issue areas of TA and IP, these effects are absent.

Despite these many similarities, both policy fields differ significantly in their underlying propensity for institutional competition. In the policy field of TA, institutional benefits are essentially non-excludable. Here, non-participating states benefit strongly from the cooperative efforts by others. As Dehejia and Genschel (1999) show, economically weak states have much less interest in institutional cooperation as compared to economically strong states. As they differ strongly regarding the size of their tax base, smaller states’ potential tax revenues losses when reducing rates are relatively low. In contrast, the positive effect of attracting foreign capital for their tax base is comparatively high. Thus, when it comes to the harmonisation of taxes, ‘cooperation would leave the small state with less tax revenue than under tax competition (absent side payments)’ (Dehejia and Genschel 1999: 411). Once a group of states engages in institutionalised cooperation to tackle the issue of TA, virtually all non-participating states benefit from the cooperating states’ efforts to harmonise their tax rates: Outsiders are not excluded but face positive externalities from the competitive self-restraint by members as they now face less competition for foreign capital (Shapiro 2001). As corporations interested in shifting their capital to a jurisdiction with low tax rates face a smaller range of potential tax havens, the race-to-the-bottom might eventually even slow down. Thus, once a group of states decides to institutionalise their cooperation on TA, other states face no more incentives to join or create alternative institutional arrangements. Furthermore, states participating in TA institutions face incentives to ‘buy non-members in’ (Kruck and Zangl 2019) to expand the scope of their rules. This, in turn, reduces inter-institutional competition in the field.

In the field of IPRs, to the contrary, institutional benefits are excludable. If states decide to abstain from a respective IPRs institution, they are excluded from privileges enjoyed exclusively by members of the ‘IPRs club’. These privileges entail access to club members’ domestic markets, or the possibility to protect own patents. Thus, the very nature of cooperation on IP standards entails the creation of institutional clubs. Conveniences associated with IP club membership cannot be enjoyed by outsiders. Quite the opposite, the creation of IP clubs creates negative externalities for states with a preference for IP deregulation. They are worse off than they were at the time before the institution was established (Slapin 2009). Ex-post-institutional creation, there are fewer potential markets for their (unlicensed) products, and they face higher prices for licensed products from club member jurisdictions. In fact, the creation of IPRs institutions forces states interested in deregulation to pay for licenses that allow the use of desperately needed foreign goods (Dosi and Stieglitz 2014: 2). Many studies have shown that countries abstaining from IPRs institution receive less foreign direct investment and less joint ventures, especially in research and development facilities (Mansfield 1995) thereby significantly hampering economic growth (Gould and Gruben 1996). Furthermore, firms from countries with high IP protection standards often tend to refuse licensing their products to companies from states only reluctantly enforcing IPRs fearing contracts will not be enforceable (see e.g. Sherwood 1990). Hence, the exclusion from benefits stemming from IPRs cooperation outweighs the costs of IPRs commitments. Thus, once IPRs institutions have been established, unilateralism is no longer a rational option, even for states with profound interests in non-cooperation. To the contrary, outsiders face strong incentives to either join institutions thereby trying to mitigate rules from within, or to engage in the creation or strengthening of alternative clubs promoting less strict IPRs protection standards to mitigate the harmful effects of non-cooperation. It becomes a rational strategy to shift cooperation to those institutional clubs providing exceptions and less strict IP rules. These tendencies rooted in the excludability of institutional benefits reinforce institutional competition in the policy field of IPRs. Here, as compared to the policy field of TA, excludability creates strong incentives for states to engage in (re-)negotiation of institutions. Strategies like competitive regime creation or regime shifting and forum shopping are rational strategies which unfold centrifugal effects on the regime complex’s underlying topology.

A comparative network analysis of the institutional complexes of TA and IP

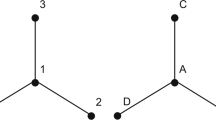

To assess the topologies underlying the complexes of TA and IP, I propose to think of them as social networks. Within these networks, each institution’s relative position shapes the overall topology of the complex. Areas dominated by one central institution with others located at the network’s outskirts exhibit strongly centralised inter-institutional network structures. Issue areas in which there is no clear-cut centre in their underlying institutional networks, to the contrary, exhibit more decentralised inter-institutional network structures.

I measure institutional networks along two important dimensions. (1) The first dimension captures instances of references among all relevant institutions within the complex. In line with Pratt (2018), I argue that structures within such inter-institutional networks are constituted by instances of inter-institutional policy coordination and deference (Pratt 2018: 562–63). These acts of recognition occur in official IO documents. If they contain the explicit reference to another IO governing the same issue area, this constitutes an IO relation and an edge among two nodes of the respective institutional complex’s network. The more an institution is referred to by all other institutions of the respective policy field, the more central its position within the institutional complex’s reference network. I complement the analysis by another dimension capturing formal participation in institutions by relevant states actively engaging in the policy field.Footnote 3 The institutional topology underlying regime complexes can be considered fragmented in policy fields where states pursue cooperation via many unrelated institutions and where references among these institutions are rather equally distributed. To the contrary, institutional structures are centralised if states pursue cooperation on a respective policy issue predominantly via universalistic, large-scale institutions and where references among institutions are directed towards one or only a tiny number of institutions. I selected the sample of states based on quantitative criteria indicating the degree to which a respective state has a substantial interest in cooperation on the respective issue.Footnote 4 To identify the relevant institutions set-up in each policy field, I consulted several existing studies of the two issue areas and their underlying institutions (Table 1).Footnote 5

For this sample of institutions, I collected more than 17.000 pages of institutional documents. These documents include annual reports, policy documentations, financial statements or statistical reports. Whenever an institution is directly mentioned within an analysed document, it is coded as a referential tie between the mentioned institution and the institution from which the document was sourced. The resulting network graphs indicate the intensity and direction of reciprocal recognition among all relevant institutions of a respective institutional complex during the period of observation. All documents collected for the institutions of both issue areas originate from 2013–2017.Footnote 6 The state membership socio-matrices, on the contrary, were coded non-directional. Ties among states and institutions are unweighted and undirected. In a binary sense, the socio-matrices contained cells for each pair of state and institution where ‘1’ indicates membership and ‘0’ indicates non-membership. The following network graphs map both the reference networks and the membership networks of the IPRs and TA’s complexes. The node size indicates an institution’s weighted number of incoming references, while the colour shading indicates its respective normalised betweenness centrality.Footnote 7

Figures 1 and 2 indicate that inter-institutional structures differ across both policy fields. Corroborating my expectations, the issue area of IPRs with its more competitive institutional environment exhibits a more fragmented topology in both the reference and the membership network as compared to the complex of TA. Here, the OECD obtains the most central position in both networks. In the issue area of IPRs, to the contrary, WIPO’s and the WTO/TRIPS positions are more contested, e.g. by the CBD or regional institutions like EPO or ARIPO. In the IPR network, institutions with a broad and rather unspecific mandate like the CBD or the WHO obtain comparatively central positions. When comparing the differences in centrality scores among institutions across both complexes, the difference in indegree and betweenness centrality to all other institutions is greater in the case of the OECD as compared to WIPO (see Appendix A.1.). In contrast to the institutional complex of TA, in the IPRs complex, institutional activity appears not to be centralised towards a clear-cut centre but spreads across several similarly centralised institutions.

Besides individual positions of institutions, diverging structures are further reflected in both reference networks’ underlying normalised indegree- and betweenness centralisations. While the reference network underlying the TA complex exhibits a high degree of in-degree and betweenness centralisation, the issue area of IPR, to the contrary, exhibits lower degrees of both, weighted indegree and betweenness centralisation.Footnote 8

Going beyond this mere co-variation analysis of market characteristics and institutional configurations, in the following section, I conduct two case studies of institutionalisation processes in both complexes. Tracing institutionalisation processes, I show that in the policy field of TA the non-excludability of institutional benefits created centripetal effects on the complex’s underlying structures strengthening particularly the OECD’s position. In the policy fields of IPRs, to the contrary, higher propensities for inter-institutional competition due to the excludability of institutional benefits created centrifugal effects on the complex’s underlying structures, resulting in more decentralised patterns of institutional cooperation through the WTO, the WHO, the CBD and other fora.

Tax avoidance institutions and the non-excludability of institutional benefits

In the issue area of TA, the non-excludability of institutional benefits played a crucial role in the OECD member states struggle to implement and expand more binding and encompassing institutions. Although the OECD had deepened its cooperation on the issue including more internal rules to avoid TA among member states, non-OECD members like Panama, the Cook Islands or Macau continuously declined any participation in their initiatives but acted as ‘renegade states’ (Eden and Kudrle 2004). Rather than facing any incentives to join the OECD’s institutional projects or creating alternative institutions by themselves, to the contrary, for a long time they benefitted from the OECD’s regulatory efforts without having to bear any costs by themselves. Most importantly, they economically profited strongly from transnational firms’ tax evasion practices in response to higher tax rates in OECD jurisdictions (Sherman 2011). In response to higher rates in many OECD states, there were huge capital shifts in particular to small tax havens (Slemrod and Wilson 2009). Due to this ‘competitive self-restraint’ for non-members there were further no incentives to strengthen alternative TA institutions which in turn strongly mitigated institutional competition in the field. Moreover, institutional competition was further hampered by the fact that the OECD actively engaged in efforts to create a more encompassing tax regime by ‘buying non-members in’, thereby weakening alternative institutional arrangements that had emerged over time, like the UN Tax Committee regional institutions like the Intra-European Organisation of Tax Administrations (IOTA).

At the latest since the early 1990s the OECD intensified its effort on tackling this growing issue of non- cooperation by tax havens (see Rixen 2008b; Lesage and van de Graaf 2015: 84–85). In 1998, the OECD introduced concrete measures to intensify international cooperation beyond its members by creating the international Forum on Harmful Tax Practices (OECD 1998: 52–55). Most importantly, the forum explicitly aimed at including noncooperators as it intended ‘that non-Member countries […] [are] associated with the recommendations to the extent possible […] [and] to ensure that the application of the guidelines by member countries will not simply result in the displacement of investment to harmful preferential regimes in non-member countries’ (Weiner and Ault 1998: 607). These considerations clearly indicate that the OECD was aware of the free-riding problem associated with institutionalised cooperation on TA. Simultaneously, the cautiously formulated ambitions also indicate that the organisation was aware that the incentives for non-members to cooperate were prohibitively low.

For a long time, economically less powerful states favoured the so-called UN Tax Model, including more source-based taxation, which corresponds more to their economic interests as compared to the OECD Tax Model favouring residence-based taxation, which corresponds more to capital-exporting interests (Baistrocchi 2013: 17). Furthermore, among non-OECD countries, pursuing cooperation on tax matters via the United Nation’s Tax Committee was perceived to be more legitimate due to its universal membership and the fact that it provides an equal voice to economically weaker countries (Lesage and van de Graaf 2015: 86). With the explicit endorsement of the much more diverse G20, in 2009, the OECD reinforced its efforts to establish institutionalised cooperation on tax matters beyond their own limited group of members. By reorganising its Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes into a non-binding institutional arrangement that is ‘open to all states and has a clearly defined purpose’ (Kudrle 2014: 205), the OECD aimed at coopting reluctant nonmembers that had so far ridden free on their tax rate increasing policies.

To incentivise reluctant non-members to participate in the proliferation of its public good, the OECD offered them benefits in exchange for institutional participation. They offered significant material and immaterial support to non-member states, e.g. through the ‘OECD- SAT Multilateral Tax Centre’, the first of its kind set up outside the OECD world in which ‘OECD tax specialists […] train local taxation civil servants’ (Clifton and Diaz- Fuentes 2014: 262). Through this centre, the OECD aims inter alia at supporting ‘a consistent implementation of BEPS outcomes [i.e. the OECD project aiming to tackle Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)] for the benefit of developing countries with almost ten events per year’ (OECD 2018: 37). Thus, the OECD aimed to guide non-members towards implementing their epistemic standards and norms, thereby reducing incentives for these states to cooperate on tax matters outside of the OECD environment.

Moreover, the OECD put strong emphasis on the fact that its cooperative arrangements with non-members are soft law legal instruments (OECD 2015: 5). This lack of an adequate enforcement mechanism allowed states to join the OECD’s arrangements without having to fear any sovereignty costs (Grinberg 2016: 166). Especially towards China, the OECD relaxed its demands from the country to not endanger its participation in its projects. In 2009, when the OECD Tax Centre reinforced its efforts against TA by publishing a list of ‘non-cooperative’ tax havens including Hong Kong and Macau, China put their cooperation with the OECD on tax matters on hold. China’s annoyance was so great that they eventually insisted on excluding the OECD from the G20 summit in London in March 2009 (Clifton and Diaz-Fuentes 2014: 73–74). In rushing obedience, the OECD removed both, Hong Kong and Macau, from its tax haven list to reassure China’s future participation in the organization’s tax initiatives. This concession was finally crowned by success. In 2013, China signed the OECD Multilateral Convention on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Tax Matters, which provides an inclusive framework enabling participating countries to swiftly implement the automatic exchange of tax information (OECD 2013).

The OECD also intensified its accommodation towards non-members through its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project which ‘provides 15 Actions that equip governments with the domestic and international instruments needed to tackle TA’ (OECD 2019b). While for its 34 member states, the OECD considers the implementation of the minimum standards of this package by legislation as obligatory, several non-member states were actively involved in the development of these standards but merely ‘invited’ to implement them by becoming ‘BEPS Associates’ (Christians 2016: 1603). This indicates the OECD’s awareness of the free-riding problem arising if members would have implemented the initiative alone. Because of the increasing tax rates and further TA instruments then implemented by OECD members, non-members would have become an even more attractive destination for corporate capital as in their jurisdictions, the strict BEPS standards were not an issue for private profits.

Consequentially, the OECD engaged in coopting non-members by inviting them to the agenda-setting and rule formulation process to increase the likelihood of their later participation, while at the same time ‘maintaining the position that the organization is not imposing any rules on sovereign states’ (ibid.: 1608). This cooptation strategy by the OECD indicates its awareness of the non-excludability of benefits associated with their cooperative efforts. Only by reducing the costs of cooperation and providing further incentives in exchange for participation, they succeeded in ‘buying non-members in’. This ‘cheap’ cooperation offer by the OECD was attractive: The uncertain legal status of the institutional arrangements offered to non-members by the OECD allowed them to be ‘opportunistic about their decision to cooperate or remain autonomous in specific tax policy matters’ (ibid.: 1616). Simultaneously, the inclusion of institutional outsiders to the agenda-setting and policy formulation stage of the project allowed non-members to shape the conditions under which BEPS cooperation takes place, thereby reducing their incentives to strengthen institutional alternatives. E.g. China used its hosting of the G20 summit in 2016 to present and underscore its ideas of relevant measures against BEPS which were finally adopted to the package (Avi- Yonah and Xu 2018: 4–5).

By catering to the interests of important non-member states thereby further reducing the attractiveness of institutional outside options, the OECD was able to fortify its central position within the institutional complex of TA: due to the non-excludability of benefits associated with cooperation on the issue, the OECD had to accommodate the interests of non-members to ensure their participation. The OECD was ultimately successful by trading institutional privileges and weakness for institutional support as many non-members joined its soft institutional arrangements like the Global Forum or BEPS.

IPRs institutions and the excludability of institutional benefits

In the policy field of IPRs the excludability of institutional benefits incentivised states to engage in strategies of regime shifting and forum shopping which translated into centripetal effects on the topology of the IPRs regime. In contrast to the policy field of TA, industrialised states’ efforts to create more binding and strict institutions were successful, because they could credibly threaten economically weak states to be excluded from future cooperation. Moreover, and in sharp contrast to the issue area of TA, non-participation in IPRs institutions was not associated with positive external effects, but with significantly negative ones. Defiant states could not expect to attract foreign capital if they refrained from cooperation like in the tax case. Quite the opposite, non- participation meant a de facto exclusion from vital (industrial) markets. Thus, there was no free-riding possible on positive externalities of IPRs, but to the contrary, strongly negative externalities forced defiant states into cooperation. However, due to the excludable nature of IPRs, there were strong incentives to counter these negative externalities by engaging in the creation of ‘alternative IPRs clubs’. Over time, these incentives led many states to engage in regime shifting, competitive regime creation or forum shopping which created centrifugal effects on the institutional complex’s topology.

During negotiations on the intake of stricter IPRs rules to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) framework in the context of the Uruguay Round (1986–1994), a broad coalition of industrialised states led by the US aimed at framing internationally binding IPRs as a normatively desirable goal and a mandatory prerequisite for fair and balanced trading agreements. Non-cooperators were accused of producing ‘broader negative effects on U.S. competitiveness, its trade balance, and American jobs’ (Sell and Prakash 2004: 158). Consequentially, only those states committing themselves to IPRs agreements should be allowed to profit from trade facilitation and enhanced access to the important sales markets within developed states. Agreeing upon the institutionalisation of strong IPRs was thereby directly linked to an enhanced potential for economic growth (Adede 2003: 31–32). Thus, in the sense of an exclusive club good, only those states agreeing upon strict IPRs rules within the GATT negotiations should profit from trade privileges. Those states who were initially reluctant to accommodate the demands of the industrialised states for stricter IPRs were increasingly pressured with threats of trade sanctions if they were to further resist enhanced IPRs protection within the GATT framework (Weissman 1996: 1078). For many economically weak countries the only option to avoid the exclusion from these important trade networks was to join the proposed club of IPR cooperators as ‘compliance with TRIPS […] [could effectively] shelter the foreign party [from US sanctions]’ (Finger and Nogues 2002: 336).

Weak economies further saw themselves increasingly confronted with the concrete risk of a complete breakdown of the Uruguay Negotiation Round if they were to further block the intake of IPRs to the trade talks as free trade was tied to strict IPRs. Developing countries (DCs) perceived it to be of the highest importance to ‘remain in the multilateral system rather than be caught in the middle of an impending trade war that might result in due to the failure of GATT […] [which] calls for a “fair” and possibly a uniform standard of patent protection laws’ (Patnaik 1992: 37). For them, solving IPR disputes multilaterally appeared to be an instrument of protection against unilateral sanctions (Correa 2000: 11). Faced with the negative consequences of exclusion from important trade markets, joining the proposed IPRs institution was considered the least evil and they eventually gave up their resistance and agreed to put IPRs on the Uruguay Negotiation Round’s agenda (Drahos 2002: 774).

When the agreement became effective in 1995, many economically weaker states faced negative externalities arising from the new IPRs club. Prices for newly licensed products increased, while many DCs had difficulties implementing the required IPRs standards domestically (Dosi and Stieglitz 2014). They subsequently started to intensify their cooperation efforts on alternative, especially more flexible IPRs rules outside the WTO as the TRIPS agreement de facto excluded them from access to vital drugs which were now patent-protected and hence unaffordable for many DCs (Daßler et al. 2019: 595–96). Consequently, a coalition of emerging countries under the leadership of Brazil and South Africa engaged in shifting the IPR issue to the World Health Organisation (WHO) (Helfer 2004: 42). As a result, the WHO indeed gradually intensified and expanded its institutional activities concerning IPRs. In its ‘revised drug strategy’ it decided about the ‘monitoring and analysis of the impact of trade agreements on essential drugs in partnership with four WHO collaborating centers […] [and to] monitor all relevant issues under discussion at WTO that may have implications for the health sector’ (WHO 2001: 4). Moreover, in 2003, at the initiative of DCs, the WHO decided to formally institutionalise the monitoring of negative consequences of IPRs for public health provisions by WHO members by establishing a whole new body with the exclusive task to examine the effect of IPRs on the development of new drugs allowing the WHO also to formulate proposals reviewing TRIPS in the future (WHO 2003; Helfer 2004: 44). Thus, to mitigate the negative effects of TRIPS, DCs engaged in gradually undermining the TRIPS agreement by shifting policy-related authority towards the WHO.

Another issue for many DCs concerned the ‘patentability’ of biological resources. To mitigate the risks of an exploitation of their rich biological resources by industrialised states enabled by TRIPS provisions, a coalition of DCs called for institutionalised solutions to this problem outside of the WTO/TRIPS framework (Helfer 2004: 28–29). For them, the Convention on Biological Resources (CBD), established in 1992, provided a possibility to pursue IPRs norms contrasting those of TRIPS, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of TRIPS on the use of their biological resources. Especially India, a country with wealthy knowledge on the traditional use of such resources, engaged in further strengthening the provisions by the CBD, which should ‘give better protection to the rights of developing countries [than TRIPS]’ (Kruger 2001: 172). Indeed, the CBD, in contrast to TRIPS, formulates concrete rights for biodiversity-rich states to ‘control genetic resources within their borders and to determine conditions of access to them. Access may be granted only upon mutually agreed terms and subject to the prior informed consent of the state providing the resources’ (Helfer 2004: 31).

Together with China, India subsequently pushed for institutionalising these norms by formulating rules and guidelines for affected members. These attempts were ultimately successful when in 2001, the CBD’s Convention of Parties (COP) decided to establish a working group of experts to address the relationship between IPRs as formulated by TRIPS and the regulation of access to and benefits from the use of genetic and biological resources (Helfer 2004: 33). Under their leadership, a coalition of Like-Minded Megadiverse Countries (LMMC) successively pushed for more and even stronger and adequate benefit-sharing mechanisms under the CBD (Daßler et al. 2019). Against the fierce resistance of many industrialised economies, the LMMC reached an agreement on the so-called Nagoya- Protocol in 2010. Among other things, it gives provider countries legal permission to restrict free access to their genetic resources and to require from users the sharing of benefits while also committing providers to establish comprehensible rules that give users legal certainty about the conditions of access and benefit-sharing (Daßler et al. 2019: 605). In sum, the threat of being excluded from critical institutional benefits had pushed DCs into institutionalised cooperation, providing rules against their interests. To mitigate these adverse effects, in the years following the establishment of the TRIPS agreement, they strove for opportunities to carry the issue of IPRs governance to alternative institutions providing them with the opportunity to create alternative IPR norms to allow for partial mitigation of the negative consequences of TRIPS. This created centrifugal effects on the institutional complex’s topology. This centrifugal dynamic was further reinforced by industrialised countries striking so-called TRIPS-plus agreements due to their dissatisfaction with the legal uncertainty surrounding TRIPS and the forum-shopping strategies applied by DCs (Sell 2007; Morin 2009). This competitive regime creation behaviour, mainly by the US and its allies, further undermined the authority of the so far focal institutions WIPO and TRIPS while reinforcing the complex’s decentralised topology.

Conclusion

This paper aimed to contribute to the literature on regime complexity in two ways. First, introducing the concept of institutional topologies allows analysing interactions among a regime complex’s constitutive actors from a network perspective allows mapping the (de)centralisation of institutional cooperation across a potentially wide range of issue areas. Second, the paper offers a novel theoretical argument to explain the oftentimes wildly varying institutional topologies underlying institutional complexes of global governance. Taking Lipscy’s (2015, 2017) theory of policy area competition and institutional change as a starting point in this paper, I emphasised the critical role of the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits in shaping institutional competition and, thus, the evolution of (de)centralised institutional topologies. More precisely, the paper has put forth the argument that institutional competition is not only a consequence of network effects and barriers to entry (Lipscy 2015, 2017) but is also shaped by the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits. Against the premise of theories explaining variation in institutional configurations merely based on individual interests or power constellation of states (Urpelainen and van de Graaf 2015; Johnson and Urpelainen 2012; Henning 2019), or the functional necessity for distinct institutional designs (Koremenos et al. 2001; Abbott and Snidal 1998) the paper introduces a structural perspective that stresses the relevance of a policy fields’ market characteristics in general, and the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits in particular.

Two important caveats are in order. First, while the comparative analysis confirms the plausibility of my theoretical argument that there is an independent effect of the (non-)excludability of institutional benefits on institutional competition and thus topologies, future research should engage in broadening the analytical focus by including more cases and more rigorous tests of the theory’s explanatory power vis-à-vis alternative explanations. Structural comparisons of more than two issue areas and their underlying topologies would further allow mapping (de)centralisation trends across numerous policy fields or different periods in time. Second, as this approach has analysed institutional topologies assuming unitary state actors, it has neither theorised nor analysed the role of transnational private actors in shaping the (de)centralization of regime complexes. As recent scholarship has begun to illude on how e.g. transnational corporate interests can be part of and actively shape authority structures within regime complexes (Green 2021), it appears promising for future research to also include these non-state actors in the theorisation and analysis of the (de)centralisation of institutional topologies. However, regarding the two cases analysed in this paper, it remains doubtful whether private interests alone can explain the variation in topologies across issue areas. At least when it comes to the issue area of TA, following the assumption that state behaviour merely reflects the interests of big corporate actors, we should not see such strong efforts by the OECD to centralise, deepen and formalise institutional cooperation. Quite the opposite, the OECD has taken the lead in recent initiatives against TA, for instance by initiating and successfully negotiating a global minimum tax rate for multinational enterprises. Although contradicting the interests of giant transnational corporations, the OECD has successfully deepened TA cooperation throughout recent years. My paper has pointed to the important role of a policy field’s underlying cooperation problem in order to grasp such centripetal dynamics in interstate cooperation. Specifically, it has shown how the non-excludability of institutional benefits shapes interstate negotiations on the issue, thereby improving our understanding of the evolution of the TA fields centralised institutional topology, but also of the variation of these structures among different issue areas in general.

Notes

Crossing both dimensions, the economic literature differentiates between purely private goods, club goods, common pool resources and public goods. For more nuanced and detailed differentiations of different types of good see e.g. Kaul et al. (2003); Barrett (2007); Sandler (2004: 82); Cornes and Sandler (1996).

In particular powerful states have profound interests in institutions that provide public goods. Such institutions can stabilise the institutional order thereby fortifying their central position and reassuring themselves against potential revisionist behaviour by emerging powers (Gowa 1989; Nye 2002; Gilpin 2016: 364 f.).

I gathered state membership status from each organisation’s official institutional website and available up-to-date documents containing membership status information.

For the policy field of TA, I consulted the OCED dataset on Statutory Corporate Income Tax Rates to identify 17 states with the relatively lowest CIT rates and 19 states with the highest CIT rates for the year 2018 (OECD 2019a). For the policy field of IPRs, I consulted the WIPO dataset on total patent applications (direct and PCT national phase entries) identifying 33 states with the highest total number of patent applications as reported for the year 2017 (WIPO 2019).

For the issue area of TA, I consulted Rixen (2008, 2011), Brauner (2002) and Christians (2010) to identify the most important multilateral tax institutions. For the issue area of IPRs, I consulted Helfer (2004), (2009), Raustiala and Victor (2004) and Sell (2017) to identify the most relevant multilateral IPR institutions.

To ensure comparability of frequencies across institutions and policy fields, I performed weighting procedures. For each 5 years, the number of references within a specific set of institutional documents was weighted by the total number of documents.

Dark shades indicate high betweenness centralities, light shades indicate low betweenness centralities. The measure of betweenness centrality captures the number of shortest paths passing through a respective node indicating how all other network institutions connect via this institution (Freeman 1977: 35).

Tables including all centralisation scores for both reference networks are available in this paper’s Appendix.

References

Abbott, K. W. and D. Snidal (2000) ‘Hard and soft law in international governance’, International Organization 54(3): 421–56.

Abbott, K. W. and D. Snidal (1998) ‘Why states act through formal international organizations’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 42(1): 3–32.

Adede, O. (2003) ‘Origins and History of the TRIPS Negotiations’, in Christophe Bellmann, Ricardo Melendez-Ortiz, eds, Trading in Knowledge: Development Perspectives on TRIPS, Trade and Sustainability, 23–35, London: Routledge.

Alter, K. J. and S. Meunier (2009) ‘The politics of international regime complexity’, Perspectives on Politics 7(1): 13–24.

Baistrocchi, E. A. (2013) ‘The International Tax Regime and the BRIC World: Elements for a Theory’, Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 33(4): 733–66.

Bernauer, T. (1995) ‘Theorie der Klub-Güter und Osterweiterung der NATO’ [‘Theory of club goods and eastward expansion of NATO’, translated by the author], Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen 79–105.

Biermann, F., P. Pattberg, H. Van Asselt and F. Zelli (2009) ‘The fragmentation of global governance architectures: A framework for analysis’, Global Environmental Politics 9(4): 14–40.

Brauner, Y. (2002) ‘An international tax regime in crystallisation’, Tax L Rev 56: 259.

Buchanan, J. M. (1965) ‘An economic theory of clubs’, Economica 32(125): 1–14.

Busch, M. L. (2007) ‘Overlapping institutions, forum shopping, and dispute settlement in international trade’, International Organization 61(04): 735–61.

Carraro, C. and D. Siniscalco (1998) ‘International Institutions and Environmental Policy: International environmental agreements: Incentives and political economy’, European Economic Review 42(3–5): 561–72.

Christians, A. (2010) ‘Taxation in a Time of Crisis: Policy Leadership from the OECD to the G20’, Nw. JL and Soc. Poly 5: 19.

Copelovitch, M. S. and Putnam T. L. (2014) ‘Design in context: Existing international agreements and new cooperation’, International Organization 68(2): 471–93.

Cornes, R. and Sandler T. (1996) The theory of externalities, public goods, and club goods, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Correa, C. M. (2000) Intellectual property rights, the WTO and developing countries: the TRIPS agreement and policy options, London: Zed Books.

Daßler, B., T. Heinkelmann-Wild and A. Kruck (2022) ‘Wann eskalieren westliche Mächte institutionelle Kontestation? Interne Kontrolle, externe Effekte und Modi der Kontestation internationaler Institutionen’ [‘When do Western powers escalate institutional contestation? Internal Control, External Effects and Modes of Contestation of International Institutions’, translated by the author], Zeitschrift für Internationale Beziehungen, forthcoming.

Daßler, B., Kruck A. and Zangl B. (2019) ‘Interactions between hard and soft power: The institutional adaptation of international intellectual property protection to global power shifts’, European Journal of International Relations 25(2): 588–612.

Dehejia, V. H. and Genschel P. (1999) ‘Tax competition in the European Union’, Politics and Society 27(3): 403–30.

Dosi, G. and Stiglitz J. E. (2014) ‘The role of intellectual property rights in the development process, with some lessons from developed countries: an introduction’ in Mario Cimoli, Giovanni Dosi, Keith E. Maskus, Ruth L. Okediji, Jerome H. Reichman, eds., Intellectual property rights: Legal and economic challenges for development, 1: 1–55, Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online.

Drahos, P. (2002) ‘Developing Countries and International Intellectual Property Standard Setting’, The Journal of World Intellectual Property 5(5): 765–89.

Eden, L. and Kudrle R. T. (2005) ‘Tax havens: Renegade states in the international tax regime?’, Law and Policy 27(1): 100–27.

Finger, J. M., & Nogues, J. J. (2002) ‘The Unbalanced Uruguay Round Outcome: The New Areas in Future WTO Negotiations’, The World Economy 25(3), 321–40.

Fischbacher, U. and Gachter S. (2010) ‘Social preferences, beliefs, and the dynamics of free riding in public goods experiments’, American Economic Review 100(1): 541–56.

Freeman, L. C. (1977) ‘A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness’, Sociometry 40 (1): 35–41.

Gehring, T. and B. Faude (2014) ‘A theory of emerging order within institutional complexes: How competition among regulatory international institutions leads to institutional adaptation and division of labor’, The Review of International Organizations 9(4): 471-98.

Genschel, P. and T. Plumper (1997) ‘Regulatory competition and international cooperation’, Journal of European Public Policy 4(4): 626–42.

Gholiagha, S., Holzscheiter, A. and Liese, A. (2020) ‘Activating norm collisions: Interface conflicts in international drug control’, Global Constitutionalism 9(2): 290-317.

Gould, D. M. and W. C. Gruben (1996) ‘The role of intellectual property rights in economic growth’, Journal of Development Economics 48(2): 323–50.

Gowa, J. (1989) ‘Rational hegemons, excludable goods, and small groups: An epitaph for hegemonic stability theory?’, World Politics 41(3): 307–24.

Green, J. F. (2021) ‘Hierarchy in Regime Complexes: Understanding Authority in Antarctic Governance’, International Studies Quarterly, forthcoming.

Grinberg, I. (2016) ‘Does FATCA teach broader lessons about international tax multilateralism?’, Global Tax Governance: 157–75.

Gruber, L. (2001) ‘Power politics and the free trade bandwagon’, Comparative Political Studies 34(7): 703–41.

Hafner-Burton, E. M., M. Kahler and A. H. Montgomery (2009) ‘Network analysis for international relations’, International Organization: 559–592.

Haftel, Y., Z., and Lenz, T. (2021) ‘Measuring institutional overlap in global governance’, The Review of International Organizations:1-25.

Hakelberg, L. (2015) ‘The power politics of international tax cooperation: Luxembourg, Austria and the automatic exchange of information’, Journal of European Public Policy 22(3): 409–28.

Heinkelmann-Wild, T., A. Kruck and B. Daßler (2021) ‘A Crisis from Within: The Trump Administration and the Contestation of the Liberal International Order’ in Böller, F. and Werner, W., eds., Hegemonic Transition, 69-86, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Helfer, L. R. (2004) ‘Regime shifting: the TRIPs agreement and new dynamics of international intellectual property lawmaking’, Yale Journal of International Law 29: 1–83.

Helfer, L. R. (2009) ‘Regime shifting in the international intellectual property system’, Perspectives on Politics 7(1): 39–44.

Henning, C. R. (2019) ‘Regime complexity and the institutions of crisis and development finance’, Development and Change 50(1): 24–45.

Hofmann, S. C. (2011) ‘Why institutional overlap matters: CSDP in the European security architecture’, Journal of Common Market Studies 49(1): 101-20.

Hofmann, S. C. (2019) ‘The politics of overlapping organizations: Hostage-taking, forum-shopping and brokering’, Journal of European Public Policy 26(6): 883-905.

Hooghe, L. and G. Marks (2015) ‘Delegation and pooling in international organizations’, The Review of International Organizations 10(3): 305–28.

Humphrey, C. (2014) ‘The politics of loan pricing in multilateral development banks’, Review of International Political Economy 21(3): 611–39.

Johnson, T. & Urpelainen, J. (2012) ‘A Strategic Theory of Regime Integration and Separation’, International Organization 66(4): 645-77.

Jupille, J. H., W. Mattli and D. Snidal (2013) Institutional Choice and Global Commerce, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Keohane, R. O. and D. G. Victor (2011) ‘The regime complex for climate change’, Perspectives on Politics 9(1): 7–23.

Kölliker, A. (2001) ‘Bringing together or driving apart the union? Towards a theory of differentiated integration’, West European Politics 24(4): 125–51.

Koremenos, B., C. Lipson C and D. Snidal (2001) ‘The rational design of international institutions’, International Organization 55(4): 761–99.

Kreuder-Sonnen, C., & Zürn, M. (2020) ‘After fragmentation: Norm collisions, interface conflicts, and conflict management’, Global Constitutionalism 9(2): 241-67.

Kruck, A., T. Heinkelmann-Wild, B. Daßler, and R. Hobbach (2022) ‘Disentangling institutional contestation by established powers: Types of contestation frames and varying opportunities for the re-legitimation of international institutions’, Global Constitutionalism: 1-25.

Kruck, A. and B. Zangl (2019) ‘Trading privileges for support: the strategic co-optation of emerging powers into international institutions’, International Theory 11(3): 318–43.

Kruger, M. (2001) ‘Harmonizing TRIPS and the CBD: A Proposal from India’, Minnesota Journal of International Law 10: 169 – 207.

Lake, D. A. (2009) ‘Relational authority and legitimacy in international relations’, American Behavioral Scientist 53(3): 331–53.

Lesage, D. and T. Van de Graaf, (eds). (2015) Rising powers and multilateral institutions, New York: Springer.

Li, J. (2016) ‘China and BEPS: From Norm-Taker to Norm-Shaker’, Bulletin for International Taxation 69.

Lipscy, P. Y. (2015) ‘Explaining institutional change: Policy areas, outside options, and the Bretton Woods institutions’, American Journal of Political Science 59(2): 341–56.

Lipscy, P. Y. (2017) Renegotiating the World Order: Institutional Change in International Relations, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mansfield, E. (1995) ‘Intellectual property protection, direct investment, and technology transfer: Germany, Japan, and the United States’, available at https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/ (accessed 12 June 2019).

Mattli, W. (1999) The logic of regional integration: Europe and beyond, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Morin, J. F. (2009) ‘Multilateralizing TRIPs‐Plus Agreements: Is the US Strategy a Failure?’, The Journal of World Intellectual Property 12(3): 175-97.

Murphy, S. (2009) ‘Free trade in Agriculture: A bad idea whose time is done’ Monthly Review 61(3): 78.

Ndikumana, L. (2015) ‘International tax cooperation and implications of globalization. Global Governance and Rules for the Post-2015 Era: Addressing Emerging Issues in the Global Environment’, Bloomsbury Academic: 73–106.

OECD (1998) ‘Harmful Tax Competition. An Emerging Global Issue.‘ OECD Secretariat, Paris.