Abstract

Recent advances in FLT3 and IDH targeted inhibition have improved response rates and overall survival in patients with mutations affecting these respective proteins. Despite this success, resistance mechanisms have arisen including mutations that disrupt inhibitor-target interaction, mutations impacting alternate pathways, and changes in the microenvironment. Here we review the role of these proteins in leukemogenesis, their respective inhibitors, mechanisms of resistance, and briefly ongoing studies aimed at overcoming resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advent of imatinib for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia set the stage for targeted therapies in other hematologic malignancies. The development of molecularly targeted inhibitors has been challenging in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) on account of the polyclonal nature of the disease and the complexity of the underlying molecular aberrations. It took 14 years from the advent of Imatinib to the approval of the first molecularly targeted agent in AML, midostaurin. However, since then several agents have been developed targeting a variety of pathways.

Despite the development of these effective agents, achieving durable remission using these drugs has been challenging. The mechanisms underlying resistance to these agents are complex and are being extensively investigated.

FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) inhibitors and Isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH) inhibitors have been successfully employed in AML, inducing complete responses in a significant proportion of patients both as monotherapy and as a part of combination regimens. However, resistance to these therapies lead to relapse and progression. Increased understanding of the mechanisms of resistance can expedite the development of new agents that overcome this resistance. Here we will review mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting FLT3 and IDH. Possible combinations designed to overcome these resistance mechanisms will also be briefly discussed.

FLT3

FLT3 is a class III tyrosine kinase composed of an extracellular immunoglobulin-like domain, a transmembrane helix, a juxtamembrane (JM) domain, and a kinase domain comprised of N and C lobes along with an activation loop that sits between them [1]. FLT3 assumes 2 conformations: inactive and active. The JM domain binds the N lobe of the tyrosine kinase domain and the activation loop; thereby stabilizing the activation loop in a closed configuration and the protein in inactive conformation. Upon binding FLT3 ligand, homodimerization occurs leading to phosphorylation of the JM domains. Phosphorylation shifts the JM domain out of an autoinhibitory position. The activation loop subsequently adopts an open conformation, revealing the ATP binding site, as demonstrated in Fig. 1A [1, 2]. FLT3 signaling activates downstream pathways: PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and STAT5 [3,4,5].

A FLT3 ligand binds FLT3 receptor with phosphorylation of the juxtamembrane domain. The activation loop assuming an open configuration, resulting in the active conformation. After phosphorylation, the PI3K/Akt, the STAT5, and the MAPK pathways are activated with alterations in transcription. B Type 1 inhibitors bind the ATP binding side regardless of ITD (red juxtamembrane domain) or TKD (red activation loop) mutations. C The left side depicts type 2 inhibitor binding a protein with an ITD mutation (red juxtamembrane domain). Type 2 inhibitors bind the activation loop, stabilizing the inactive conformation. On the right side, the TKD mutation (red activation loop), shifts the activation loop into an open conformation. The type 2 inhibitor is unable to bind, permitting ATP binding. Figure created with Biorender.com.

FLT3 is expressed in CD34+ progenitor cells, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and T cells. FLT3 in conjunction with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is involved in hematopoiesis and differentiation of dendritic and natural killer cells [6].

Role in leukemogenesis

FLT3 is upregulated in a substantial fraction of AML patients with growth mediated by ligand binding [7]. However, FLT3 mutations are observed in 30–35% of patients [8]. These include FLT3 internal tandem duplications (ITD) mutations and FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) mutations. FLT3-ITD mutations comprise ~80% of all FLT3 mutations [8, 9].

The FLT3 gene is located on chromosome 13. FLT3-ITD mutations occur on exon 11, between codons 590 and 600. These mutations alter the length of JM domain; thereby disrupting the autoinhibitory interaction between the JM domain and the N lobe. While the length of tandem duplications does not impact prognosis, the positioning and charge at R595 is vital for survival of the clone [10]. FLT3-TKD mutations occur at exon 17, codon 835 [9]. These point mutations result in amino acid changes in the activation loop. With these mutations, the protein remains in the active conformation with the activation loop in an open configuration [6, 11].

The prognosis of FLT3-ITD mutations is determined by the allelic ratio and co-mutation with NPM1. In the European LeukemiaNet stratification of AML, FLT3-ITD mutations with allelic ratios of FLT3-ITD to FLT3-WT less than 0.5 with a concomitant NPM1 are favorable, FLT3-ITD mutations with allelic ratios of FLT3-ITD to FLT3-WT <0.5 without a concomitant NPM1 or FLT3-ITD with high (FLT3-ITDhigh) allelic ratios (>0.5) with a concomitant NPM1 mutation are intermediate risk, and FLT3-ITDhigh with wild type NPM1 is considered adverse risk [12]. FLT3-ITDhigh is independently associated with decreased overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) [9].

Singularly, FLT-TKD mutations do not confer decreased survival in patients with AML; however, there are trends to decreased overall survival in patients with a co-occurring FLT3-ITD or a co-occurring MLL-partial tandem duplication mutations, as demonstrated by Bacher et al. [13].

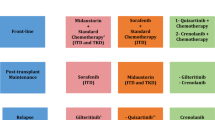

FLT3 inhibitors

Inhibitors targeting FLT3 are categorized by the conformation they bind and their specificity, as depicted in Table 1. Type 1 inhibitors inhibit the ATP binding pocket and are not dependent on conformation, as demonstrated in Fig. 1B [14]. Type 2 inhibitors stabilize FLT3 in the inactive conformation with the activation loop in a closed configuration (phenyalanine in the DFG motif protruding into the hydrophobic groove). As FLT3-TKD mutations disrupt the activation loop, maintaining an open configuration, Type 2 inhibitors are unable to bind FLT3 in this context, as demonstrated in Fig. 1C [15]. FLT3 inhibitors are further characterized based on specificity.

First-generation FLT3 inhibitors are broad kinase inhibitors [16]. This generation of inhibitors includes sorafenib and midostaurin. Sorafenib, in particular, has a broad kinase profile with the initial trials utilizing sorafenib in the relapsed/refractory setting regardless of FLT3 mutations status in part due to this broad activity. Sorafenib alone and in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated significant activity in patients with FLT3 mutations [17]. Midostaurin was the first FLT3 inhibitor approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating patients with FLT3-mutated AML, in combination with chemotherapy [18]. The phase 3, CALGB10603 demonstrated a survival benefit with the addition of midostaurin to chemotherapy with a 4-year OS of 51% as compared to chemotherapy at 44% [19].

Second-generation Type 1 (gilteritinib and crenolanib) and Type 2 (quizartinib) inhibitors are more specific for FLT3 kinase. Gilteritinib has been approved by the FDA, for patients with relapsed FLT3 (ITD and TKD) mutated AML [20]. Monotherapy with gilteritinib and quizartinib has shown superior response rates in FLT3 mutant relapsed/refractory AML when compared to standard salvage chemotherapy as demonstrated by the phase 3 ADMIRAL and QuANTUM-R trials, respectively [21, 22].

Regardless of type, FLT3 inhibitor monotherapy in patients with FLT3-ITD mutations induces responses in 2 distinct patterns: differentiation in which mature myeloid cells with FLT3-ITD mutations can be detected and cytotoxicity in which a hypocellular marrow is initially present, usually resulting in lower FLT3-ITD VAF as compared to the differentiation pattern [23, 24].

Resistance mechanisms

Despite the activity of FLT3 inhibition in the frontline and relapsed/refractory disease, 30–45% of patients relapse on therapy [25,26,27]. Resistance occurs through a variety of mechanisms: FLT3 mutations, secondary mutations impacting other pathways, and factors within the micro-environment. These processes are not mutually exclusive and co-occur frequently [28].

FLT3 mutations

Type 2 inhibitors maintain the inactive, closed-loop conformation. Secondary FLT3-TKD mutations alter the activation loop, occurring in ~30% of patients at the time of progression on treatment with type 2 FLT3 inhibitor-based therapies [29]. The majority of these mutations target the D835(D835V, D835F, and D835Y) residue. A variety of subclones can exist with: FLT3-TKD without FLT3 ITD, FLT3 -ITD without FLT3-TKD mutations, and clones with multiple FLT3-TKD mutations [30]. While most patients who develop resistance to therapy with TKD mutations do so after treatment, clonal evolution with TKD mutated subclones does occur as illustrated by Baker et al. [28].

TKD mutations affecting the activation loop are uncommon mechanisms of resistance in patients on Type 1 inhibitors. However, mutations in other areas including F691L (gatekeeper mutation within the active site), Y693C, Y693N, and D698N may still confer resistance to Type 1 inhibitors [26, 31]. These mutations alter binding to the active site with resulting residue changes affecting side chains, aromaticity, direct steric clash, and indirect steric clash [31, 32].

While uncommon, ITD mutations can also occur within the kinase domains, as demonstrated by Breitenbuecher et al. in a patient treated with midostaurin [33]. Clonal evolution that selects for certain FLT3-mutated populations can occur leading to the expansion of FLT3 inhibitor-resistant subclones. Increased MCL1, persistent ERK activation, and increased STAT3 phosphorylation were noted in these patients. STAT3 and MCL1 inhibition resulted in response to therapy [33].

Secondary mutations in other pathways

Mutations impacting parallel pro-survival pathways are common mechanisms of resistance with targeted therapies. In regard to FLT3 inhibitors, a diverse range of mutations are utilized by leukemic clones in order to promote resistance.

RAS pathway mutations are the most common mutation-derived mechanism of resistance to type 1 inhibitors, occurring in ~30% of patients who relapse after having achieved a remission to type 1 inhibitors. These mutations can occur as new mutations after treatment or as clonal expansion with increasing variant allele frequency (VAF) throughout the treatment course. Higher variant allele frequencies in RAS/MAPK mutations are associated with poorer outcomes in both primary and secondary relapse settings. Compared to type 1 inhibitors, RAS pathway mutations occur less frequently with type 2 inhibition, occurring in only 6% of patients relapsing post type 2 inhibitors [34]. While FLT3-TKD mutations are the predominant mechanism of resistance with type 2 inhibitors, single-cell DNA sequencing in patients receiving quizartinib showed RAS-mutated clones can expand independent of FLT3 mutations or concomitantly with FLT3-TKD mutations [35].

A myriad of other mutations contributes to resistance. In one study investigating resistance to crenolanib, the VAFs of various mutations were monitored prior to the initiation of therapy until relapse. Germline TET2, RUNX1, U2AF1, DNMT3A, IDH1, and SF3B1 were noted to be pre-existing with VAFs in some patients 50% or more. Notably, the VAFs remained constant throughout therapy, suggesting primary resistance in the founder clone, despite FLT3 inhibition. Other mutations such as ASXL1, BCOR, STAG2, and CEBPA had an increase in VAF suggesting that these mutations could be contributing to resistance [26]. Parallel tyrosine kinase pathways can also be utilized for resistance with JAK and PI3K/AKT known to be associated with resistance to gilteritinib, sorafenib, and midostaurin [36, 37].

The microenvironment and cytokines

The bone marrow environment plays an important role in the preservation of FLT3 mutated clones. Preservation of leukemic clones can be mediated by cytokines and growth factors released from the bone marrow microenvironment. Interactions between stromal cells and leukemic cells also contribute to resistance [38].

Cytokines such as CCL5 (receptor CCR5) and receptors such as CXCR4 (ligand CXCL12) play important roles in stem cell localization and survival. Elevated levels of CCL5 and the expression of CXCR4 on leukemic cells result in downstream ERK and Akt activation, promoting survival and disrupting migration of these cells to the blood. These cytokines have been shown to promote survival of FLT3 clones in a kinase-independent manner [39,40,41,42]. Furthermore, pre-clinical studies in mouse models have shown that the transcription of CXCR4 in addition to E-selectin ligand are upregulated after exposure to quizartinib, suggesting that evasion, utilizing niches within the bone marrow microenvironment, is an important component to resistance [43].

In an in vitro and in vivo study investigating the relationship between growth factors and resistance to therapy, GM-CSF resulted in activation of the RAS and the AKT pathways. In addition, GM-CSF induce activation of PIMs, anti-apoptotic kinases, in a JAK2 dependent manner. The administration of PIM and JAK2 inhibitors in combination with FLT3 inhibitors resulted in decreased survival of previously resistant clones [44]. Similarly, in another in vitro study utilizing quizartinib, FGF2 (a growth factor produced by the stroma) promoted survival of leukemic cells. FGF2 was expressed primarily by the stroma and peaked early in resistance, declining thereafter. Upon binding FGF2, leukemia cells will activate FGFR1 and by extension the MAPK pathway. Interestingly, removing FGF2 or FLT3 ligand-mediated signaling resulted in secondary mutations or clonal evolution of cells with RAS/MAPK mutations [45].

The microenvironment is dynamic and changes with therapy. FLT3 ligand in relapsed patients after intensive chemotherapy was found to be significantly higher [46]. FLT3 ligand binds FLT3-WT activating ERK, AKT, and downregulating pro-apoptotic proteins. The activation of these pathways via FLT3-WT promotes survival despite FLT-ITD inhibition [47].

Taken together, the microenvironment plays an important role in the preservation of leukemic cells via activation of alternative pathways involved in survival and apoptosis. Based on the cytokine profile in the marrow, diverse subclones can exist dependent to varying degrees on cytokines in the environment.

Overcoming resistance

As a result of the diverse mechanisms of resistance to FLT3 inhibitors, a multitude of agents targeting downstream pathways have been studied. A phase 1 study utilizing pacritinib (a JAK and FLT3 inhibitor) in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated limited effectiveness with 3 of 13 patients responding [48]. In vivo studies have shown improved survival in mouse models with the combination of FLT3 inhibitors with MEK inhibitors, JAK inhibitors, and dasatinib (a multi-kinase inhibitor targeting BCR-ABL, c-KIT, and Src kinases) [49, 50].

FLT3 inhibitors induce remissions in two patterns: differentiation and cytotoxic with differentiation associated with higher residual VAFs [23, 24]. Combination with pro-apoptotic agents such as venetoclax, may improve survival and response by increasing the cytotoxic activity [51]. Pre-clinical models with a FLT3 inhibitor and venetoclax demonstrated synergy even in samples with resistance to FLT3 inhibitor monotherapy [52, 53]. Results from the ongoing phase 1b trial with venetoclax and gilteritinib combination therapy have yielded promising results in the relapsed or refractory setting with a composite response rate of 78 and 60% in patients with prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy and prior venetoclax, respectively [54].

The most promising results have been with the triplet therapy: a FLT3 inhibitor, venetoclax, and a hypomethylating agent. In a report by Maiti et al., combination of venetoclax, decitabine, and a FLT3 inhibitor of clinician’s choice in the relapse or refractory setting yielded a composite response rate of 63% in patients who had prior tyrosine kinase inhibitors [55]. An ongoing phase 1–2 trial utilizing azacitidine with venetoclax and gilteritinib demonstrated an overall response rate of 67% and an overall survival of 10.5 months in relapsed patients including patients with prior transplant and prior treatment with FLT3 inhibitors [56].

Finally, therapies targeting the microenvironment are under development. Uproleselan, a E-selectin inhibitor, in particular has shown promise in AML, inducing a composite response of 41% when combined with chemotherapy in relapse or refractory setting [57]. In light of upregulation of E-selectin in patients with quizartinib exposure, combination therapy with uproleselan and a FLT3 inhibitor may overcome microenvironment induced resistance mechanisms.

IDH

Both isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) share similar structures consisting of 2 subunits forming a homodimer with each subunit comprised of a large domain, a small domain, and a clasp domain. The active site is comprised of a combination of a large domain of one subunit with a small domain of another subunit. The clasp domain holds the unit together and plays an important role in maintaining the active site. Another site called the back cleft consists of large and small domains on one subunit. This site is important for maintaining conformation [58].

IDH enzymes function within the Krebs cycle in a 2-step process converting isocitrate to oxalosuccinate, reducing NADP+ to NADPH, followed by decarboxylation resulting in the formation of α-ketoglutarate [59]. These enzymes assume 2 conformations: an open conformation and a closed conformation. The closed conformation is required for catalytic activity [60]. In addition to its role in metabolism, IDH plays an important role in preventing and addressing oxidative damage via production of NADPH and activation of HIF1α [61].

Leukemogenesis

Mutations affecting proteins involved in metabolism with resulting metabolic derangements is an established step in carcinogenesis. IDH mutations, specifically, occur in ~18% of patients with AML, in particular the elderly and in patients with normal karyotypes. While patients with pre-existing IDH mutations are at increased risk of developing AML, they usually require another driver mutation in order to induce transformation of pre-leukemic clones to AML [62]. As a result, they can occur early or late in the process of leukemogenesis. In one study utilizing single-cell sequencing, two clones with IDH1 and IDH2 mutations followed an initial NPM1, DNMT3A, or RUNX1 mutation, a pattern that is well elucidated as these commonly occur together [63].

Mutations affecting IDH function occur in the active site: R132 in IDH1, R140 and R172 in IDH2, respectively [64]. Unlike mutations occurring in FLT3 or other kinases that augment the underlying function, IDH mutations results in neomorphic enzymatic activity. As a result, IDH reduces α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydoxyglutarate (2HG), an oncometabolite which competitively inhibits aKG, as represented in Fig. 2A [65].

A Mutations of IDH occur at the active site, resulting in neomorphic activity. 2HG production results in hypermethylation, increased BCL2 expression, and altered metabolism. B IDH inhibitors function by stabilizing the open conformation, preventing catalytic activity. Figure created with Biorender.com.

2HG interferes with metabolism and suppresses the Krebs cycle, decreasing the availability of α-ketoglutarate. As a result, α-ketoglutarate is generated via upregulated glutamine metabolism, a form of anapleresis, supplying carbon for both 2HG production and the Krebs cycle [66].

Independent of its function within the Krebs cycle, α-ketoglutarate binds KDM4a, TET2, and ALKBH3, enzymes important in DNA repair and methylation. 2HG binds these enzymes and inhibits them, resulting in progressive DNA damage, increased methylation (CpG island methylator phenotype), and preventing differentiation. These are thought to be the primary mechanisms by which IDH mutations contribute to leukemogenesis [65].

Finally, 2HG inhibits cytochrome C oxygenase, a component of the mitochondrial electron transport chain located in the mitochondrial membrane and an enzyme involved in addressing reactive oxygen species. While the exact underlying mechanism is unknown, inhibition results in increased expression of BCL-2. Increased BCL2 sequesters pro-apoptotic proteins, preventing apoptosis in leukemic cells [67, 68].

In summary, IDH mutations alter metabolism, confer resistance against differentiation, and upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins, promoting leukemogenesis.

IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors

IDH1 and IDH2 inhibitors both bind allosteric sites preventing their respective proteins from assuming a closed conformation required for catalytic activity. There are 2 FDA-approved IDH inhibitors: ivosidenib, an IDH1 inhibitor, and enasidenib, an IDH2 inhibitor. IDH inhibitors bind the homodimer interface, altering binding of NADPH and stabilize the open conformation of the protein (Fig. 2B). Both of these drugs result in significant reduction in the production of 2HG [69,70,71].

Enasidenib was the first FDA-approved IDH inhibitor, specifically in the relapsed and refractory IDH2-mutated setting. The ORR was 40.3%, CR/CRi rate was 26.8%, and a median OS of 9.3 months. The median duration of response in patient achieving CR/CRi was almost 6 months [72, 73].

The efficacy, safety, and FDA approval of ivosidenib was similarly established in a phase 1 trial of relapsed/refractory patients with IDH1-mutated AML. As single-agent therapy, the ORR was 41.6%, CR/CRi rate was 30%, with a median OS of 8.3 months [74]. Analysis of 34 treatment naïve patients suggested efficacy in the frontline setting with an ORR of 42.4% and a median OS of 12.6 months, leading to FDA approval for ivosidenib monotherapy for both relapsed/refractory as well as newly diagnosed, older chemotherapy-ineligible patients with IDH1-mutated AML. This trial also suggested that IDH1 mutation clearance by digital PCR (sensitivity 0.02–0.04%) was associated with increased duration of response and could be utilized as a method of MRD detection [75]. More recently, the preliminary data from the ongoing phase 3 AGILE study showed superior response and survival with the combination of ivosidenib and azacitidine compared to azacitidine with placebo with an ORR of 63% and 19% and an overall survival of 24 and 8 months, respectively [76].

Resistance mechanisms

Leukemogenesis via IDH mutations is partially dependent on hypermethylation preventing differentiation. IDH inhibitors rapidly prevent 2HG production, which promotes differentiation through reversal of hypermethylation. Resistance to IDH inhibition occurs through multiple mechanisms, including 2HG rescue through second site mutations or isoform switching, preservation of a hyper-methylator phenotype through mutations in key transcription factors involved in differentiation (RUNX1, GATA2, CEBPA), as well as clonal evolution and expansion of receptor tyrosine kinase pathway mutations (i.e., KRAS, NRAS, PTPN11, FLT3). Importantly, a number of these mechanisms can coexist representing the complexity involved in the leukemic response to targeted inhibition.

2-hydroxyglutarate rescue

IDH mutations are heterozygous. Mutations conferring resistance can occur on the same allele that is affected or the opposite allele. Normally IDH2 mutations alter amino acid expression localized to the dimer interface. Mutations occurring on the opposite allele, trans-mutations, include Q316E and I319M can confer resistance. These mutations change the structure of the enasidenib binding site on the dimer interface. As a result, enasidenib cannot bind the protein. These can also occur within the same allele, resulting in cis-mutation mediated resistance and increased 2HG [77]. Isoform switching in patients on enasidenib is rare. However, the IDH1-R132 has been shown to rescue 2HG production [78].

In an analysis of patients who relapsed while receiving ivosidenib, second-site IDH1 and IDH2 mutations were noted in 14% and 12% of patients, respectively. IDH1 mutations cause steric interference and protein conformation changes, preventing binding of ivosidenib. IDH2-R140Q was the only emerging IDH2 mutations noted. Single-cell sequencing elucidated the roles of isoform switching and IDH2-mutated clonal evolution. Three different patterns of IDH2 mediated resistance exist: pre-treatment IDH2 clones that expand, new onset IDH2 mutations in the same clone, or IDH2 mutations in another clone, separate from the IDH1-mutated clone. The resulting rescue of 2HG suggests a dependence on this pathway for survival [79].

Altered methylation and differentiation

In a study investigating the role of leukemia stemness in IDH inhibitor resistance, two distinct clusters with differing degrees of methylation were identified in pre-treatment samples. The hypermethylated cluster had decreased response compared to more hypomethylated cluster. Hypermethylated regions included promoters for RUNX1 and other proteins involved in differentiation. Of note, both clusters had significant demethylation after therapy with the hypermethylated cluster remaining comparatively more hypermethylated after treatment.

Mutation analysis was conducted after treatment, with mutations relating to methylation occurring in 17% of samples on relapse, mainly involving DNMT3A and TET2. Mutations involving RUNX1 and other transcription factors (CEBPA and GATA2) involved in differentiation were associated with worse prognosis.

Finally, this study details 3 patterns of resistance: RAS activation, TET2 mutations, and IDH1 mutations with the latter 2 associated with increased methylation at relapse, elucidating the importance of maintaining methylation and the prevention of differentiation [80].

Clonal evolution and secondary mutations

RAS and RTK pathway mediated resistance is common to both types of inhibitors. Differentiating co-occurring mutations that grant resistance to therapy and mutations that occur after therapy impart understanding of leukemogenesis. Clonal evolution plays an essential role in mediating resistance to therapy in enasidenib-resistant patients. Expansion of co-mutated clones with FLT3, RUNX1, and RAS pathway mutations, respectively, confer a survival advantage [78]. In patients receiving ivosidenib, RAS pathway mutations were associated with lower VAF IDH1 mutation status, suggesting a complex system in which multiple clones exist dependent to varying degrees on 2HG. In addition, it suggests the existence of clones without IDH1 mutations. Nonetheless, response to IDH inhibition did not correlate to pre-treatment IDH VAF levels [80].

In summary, IDH inhibitor-mediated resistance is complex and dictated by a multitude of factors. Understanding 2HG rescue, the persistence of hypermethylation, and second site mutations and their interaction with each other, elucidates possible targets for therapy after IDH inhibitor resistance.

Overcoming resistance

Multiple ongoing trial are addressing the various mechanisms of resistance to IDH inhibitors. The addition of hypomethylating agents to IDH inhibitors has improved ORR [81, 82]. Similar results have been noted with IDH inhibitor therapy with 7 + 3 [83]. Venetoclax, a BCL2 inhibitor, in combination with hypomethylating agents has been shown to be efficacious in IDH-mutated AML, with an emphasis on IDH2-mutated AML [84, 85]. Preliminary data from triplet therapy involving ivosidenib, venetoclax, and azacitidine appears to be promising. This combination in particular is notable due to the degree of MRD negative rates, up to 60% in both newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory venetoclax and ivosidenib naïve patients. This combination directly addresses 2HG, the hypermethylated phenotype, upregulated anti-apoptotic mechanisms, and the polyclonal nature of IDH resistance [86]. Finally, several Pan-IDH inhibitors targeting both IDH1 and IDH2 isoforms are currently in early clinical trials [87].

Discussion

FLT3 and IDH inhibitors represent 2 success stories in the treatment of AML, contributing to safe and efficacious regimens.

Resistance to these therapies is complicated and involves a multitude of mechanisms. For FLT3, a receptor tyrosine kinase, resistance occurs via primary mutations, secondary mutations, and changes in the microenvironment. For IDH, an enzyme that generates 2HG, resistance is dependent on 2HG rescue, changes in methylation homeostasis, clonal evolution, and secondary mutations.

The solution for resistance toward these inhibitors resides in combination regimens and novel, more potent inhibitors. Combination regimens involving these inhibitors in particular with venetoclax and hypomethylating agents have improved response and decreased resistance. Unfortunately, RAS pathway mutations continue to be a major obstacle preventing durable remissions. Further studies into the leukemogenesis before and after therapy need to be conducted in order to appropriately address these patients.

Data availability

As no new data was generated for this manuscript, data sharing is not applicable.

References

Grafone T, Palmisano M, Nicci C, Storti S. An overview on the role of FLT3-tyrosine kinase receptor in acute myeloid leukemia: biology and treatment. Oncol Rev. 2012;6:64–74.

Griffith J, Black J, Faerman C, Swenson L, Wynn M, Lu F, et al. The structural basis for autoinhibition of FLT3 by the juxtamembrane domain. Mol Cell. 2004;13:169–78.

Darici S, Alkhaldi H, Horne G, Jørgensen HG, Marmiroli S, Huang X. Clinical medicine targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR in AML: rationale and clinical evidence. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2934.

Wingelhofer B, Maurer B, Heyes EC, Cumaraswamy AA, Berger-Becvar A, de Araujo ED, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of STAT5 in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk. 2018;32:1135–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-017-0005-9.

Takahashi S. Downstream molecular pathways of FLT3 in the pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukemia: biology and therapeutic implications. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2011;4:13.

Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. The roles of FLT3 in hematopoiesis and leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1532–42.

Hayakawa F, Towatari M, Kiyoi H, Tanimoto M, Kitamura T, Saito H, et al. Tandem-duplicated Flt3 constitutively activates STAT5 and MAP kinase and introduces autonomous cell growth in IL-3-dependent cell lines. Oncogene. 2000;19:624–31.

Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, Harrison G, Langabeer SE, Belton AA, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98:1752–9.

Thiede C, Steudel C, Mohr B, Schaich M, Schä U, Platzbecker U, et al. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–35.

Vempati S, Reindl C, Kaza SK, Kern R, Malamoussi T, Dugas M, et al. Arginine 595 is duplicated in patients with acute leukemias carrying internal tandem duplications of FLT3 and modulates its transforming potential. Blood. 2007;110:686–94.

Abu-Duhier FM, Goodeve AC, Wilson GA, Care RS, Peake IR, Reilly JT. Identification of novel FLT-3 Asp835 mutations in adult acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:983–8. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2001.02850.x.

Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–47.

Bacher U, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T, Schnittger S. Prognostic relevance of FLT3-TKD mutations in AML: the combination matters—an analysis of 3082 patients. Blood. 2008;111:2527–37.

Levis M, Perl AE. Gilteritinib: potent targeting of FLT3 mutations in AML. Blood Adv. 2020;4:1178–91.

Zorn JA, Wang Q, Fujimura E, Barros T, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the FLT3 kinase domain bound to the inhibitor quizartinib (AC220). PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0121177.

Short NJ, Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, Daver N. Emerging treatment paradigms with FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2019;10:204062071982731.

Ravandi F, Cortes JE, Jones D, Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Konopleva MY, et al. Phase I/II study of combination therapy with sorafenib, idarubicin, and cytarabine in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1856–62.

Levis M. Midostaurin approved for FLT3-mutated AML. Blood. 2017;129:3403–6.

Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, Laumann K, Geyer S, Bloomfield CD, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. 2017;377:454–64. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614359.

Pulte ED, Norsworthy KJ, Wang Y, Xu Q, Qosa H, Gudi R, et al. FDA approval summary: gilteritinib for relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3515–21.

Cortes JE, Khaled S, Martinelli G, Perl AE, Ganguly S, Russell N, et al. Quizartinib versus salvage chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukaemia (QuANTUM-R): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:984–97.

Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, Neubauer A, Berman E, Paolini S, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. 2019;381:1728–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1902688.

Nybakken GE, Canaani J, Roy D, Morrissette JD, Watt CD, Shah NP, et al. Quizartinib elicits differential responses that correlate with karyotype and genotype of the leukemic clone. Leuk. 2016;30:1422.

McMahon CM, Canaani J, Rea B, Sargent RL, Qualtieri JN, Watt CD, et al. Gilteritinib induces differentiation in relapsed and refractory FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv 2019;3:1581.

Cortes JE, Khaled S, Martinelli G, Perl AE, Ganguly S, Russell N, et al. Quizartinib versus salvage chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukaemia (QuANTUM-R): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:984–97.

Zhang H, Savage S, Schultz AR, Bottomly D, White L, Segerdell E, et al. Clinical resistance to crenolanib in acute myeloid leukemia due to diverse molecular mechanisms. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08263-x.

Perl AE, Martinelli G, Cortes JE, Neubauer A, Berman E, Paolini S, et al. Gilteritinib or chemotherapy for relapsed or refractory FLT3-mutated AML. 2019;381:1728–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1902688.

Baker SD, Zimmerman EI, Wang YD, Orwick S, Zatechka DS, Buaboonnam J, et al. Emergence of polyclonal FLT3 tyrosine kinase domain mutations during sequential therapy with sorafenib and sunitinib in FLT3-ITD-positive acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5758–68.

Swaminathan M, Kantarjian HM, Levis M, Guerra V, Borthakur G, Alvarado Y, et al. A phase I/II study of the combination of quizartinib with azacitidine or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica. 2021;106:2121–30.

Smith CC, Paguirigan A, Jeschke GR, Lin KC, Massi E, Tarver T, et al. Heterogeneous resistance to quizartinib in acute myeloid leukemia revealed by single-cell analysis. Blood. 2017;130:48–58.

Tarver TC, Hill JE, Rahmat L, Perl AE, Bahceci E, Mori K, et al. Gilteritinib is a clinically active FLT3 inhibitor with broad activity against FLT3 kinase domain mutations. Blood Adv. 2020;4:514–24.

Mcmahon CM, Ferng T, Canaani J, Wang ES, Morrissette JJD, Eastburn DJ, et al. Clonal selection with RAS pathway activation mediates secondary clinical resistance to selective FLT3 inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia secondary resistance to selective FLT3 inhibition in AML. Cancer Disco. 2019;9:1050–63.

Breitenbuecher F, Markova B, Kasper S, Carius B, Stauder T, Bö FD, et al. A novel molecular mechanism of primary resistance to FLT3-kinase inhibitors in AML. Blood 2009;113:4063-73.

Alotaibi AS, Yilmaz M, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Loghavi S, Kadia TM, DiNardo CD, et al. Patterns of resistance differ in patients with acute myeloid leukemia treated with type I versus type II FLT3 inhibitors. Blood Cancer Disco. 2021;2:125–34.

Peretz CAC, McGary LHF, Kumar T, Jackson H, Jacob J, Durruthy-Durruthy R, et al. Single-cell DNA sequencing reveals complex mechanisms of resistance to quizartinib. Blood Adv. 2021;5:1437–41.

Rummelt C, Gorantla SP, Meggendorfer M, Charlet A, Endres C, Döhner K, et al. Activating JAK-mutations confer resistance to FLT3 kinase inhibitors in FLT3-ITD positive AML in vitro and in vivo. Leukemia. 2020;35:2017–29.

Lindblad O, Cordero E, Puissant A, Macaulay L, Ramos A, Kabir NN, et al. Aberrant activation of the PI3K/mTOR pathway promotes resistance to sorafenib in AML. Oncogene. 2016;35:5119.

Parmar A, Marz S, Rushton S, Holzwarth C, Lind K, Kayser S, et al. Stromal niche cells protect early leukemic FLT3-ITD+ progenitor cells against first-generation FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2011;71:4696–706.

Yang X, Sexauer A, Levis M. Bone marrow stroma-mediated resistance to FLT3 inhibitors in FLT3-ITD AML is mediated by persistent activation of extracellular regulated kinase. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:61.

Zeng Z, Xi Shi Y, Samudio IJ, Wang RY, Ling X, Frolova O, et al. Targeting the leukemia microenvironment by CXCR4 inhibition overcomes resistance to kinase inhibitors and chemotherapy in AML. Blood. 2009;113:6215–24.

Rashidi A, Uy GL. Targeting the microenvironment in acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10:126.

Waldeck S, Rassner M, Keye P, Follo M, Herchenbach D, Endres C, et al. CCL5 mediates target‐kinase independent resistance to FLT3 inhibitors in FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML. Mol Onco. 2020;14:779.

Jia Y, Basyal M, Ostermann LB, Chang KH, Zhang Q, Fogler WE, et al. FLT3 inhibitors upregulate CXCR4 and E-selectin ligands and CD44 Via ERK suppression in AML cells, and blockade of CXCR4 and E-selectin signaling with GMI-1359 overcomes AML resistance to quizartinib in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2021;138:1171–1171.

Sung PJ, Sugita M, Koblish H, Perl AE, Carroll M. Hematopoietic cytokines mediate resistance to targeted therapy in FLT3-ITD acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2019;3:1061–72.

Traer E, Martinez J, Javidi-Sharifi N, Agarwal A, Dunlap J, English I, et al. FGF2 from marrow microenvironment promotes resistance to FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6471–82.

Sato T, Yang X, Knapper S, White P, Smith BD, Galkin S, et al. FLT3 ligand impedes the efficacy of FLT3 inhibitors in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2011;117:3286–93.

Chen F, Ishikawa Y, Kiyoi H, Naoe T. Mechanism of FLT3 ligand dependent resistance to FLT3 inhibitors. Blood. 2014;124:908–908.

Jeon JY, Zhao Q, Buelow DR, Phelps M, Walker AR, Mims AS, et al. Preclinical activity and a pilot phase I study of pacritinib, an oral JAK2/FLT3 inhibitor, and chemotherapy in FLT3-ITD-positive AML. Invest N. Drugs. 2020;38:340.

Weisberg E, Liu Q, Nelson E, Kung AL, Christie AL, Bronson R, et al. Using combination therapy to override stromal-mediated chemoresistance in mutant FLT3-positive AML: synergism between FLT3 inhibitors, dasatinib/multi-targeted inhibitors and JAK inhibitors. Leukemia 2012;26:2233–44.

Morales ML, Arenas A, Ortiz-Ruiz A, Leivas A, Rapado I, Rodríguez-García A, et al. MEK inhibition enhances the response to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Rep. 2019;9:18630.

Altman JK, Perl AE, Hill JE, Rosales M, Bahceci E, Levis MJ. The impact of FLT3 mutation clearance and treatment response after gilteritinib therapy on overall survival in patients with FLT3 mutation–positive relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Med. 2021;10:797–805. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3652.

Mali RS, Zhang Q, DeFilippis RA, Cavazos A, Kuruvilla VM, Raman J, et al. Venetoclax combines synergistically with FLT3 inhibition to effectively target leukemic cells in FLT3-ITD+ acute myeloid leukemia models. Haematologica. 2021;106:1034–46.

Zhu R, Li L, Nguyen B, Seo J, Wu M, Seale T, et al. FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors synergize with BCL-2 inhibition to eliminate FLT3/ITD acute leukemia cells through BIM activation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:1–11.

Daver N, Perl A, Maly J, Levis M, Ritchie E, Litzow M, et al. Venetoclax in combination with gilteritinib demonstrates molecular clearance of FLT3 mutation in relapsed/refractory FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2021;138:691.

Maiti A, DiNardo CD, Daver NG, Rausch CR, Ravandi F, Kadia TM, et al. Triplet therapy with venetoclax, FLT3 inhibitor and decitabine for FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:1–6.

Short N, DiNardo C, Daver N, Nguyen D, Yilmaz M, Kadia T, et al. A triplet combination of azacitidine, venetoclax and gilteritinib for patients with FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: results from a phase I/II study. Blood. 2021;138:696.

DeAngelo DJ, Jonas BA, Liesveld JL, Bixby DL, Advani AS, Marlton P, et al. Phase 1/2 study of uproleselan added to chemotherapy in patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2022;139:1135–46.

Zhao S, Guan KL. IDH1 mutant structures reveal a mechanism of dominant inhibition. Cell Res. 2010;20:1279–81.

Molenaar RJ, Maciejewski JP, Wilmink JW, van Noorden CJF. Wild-type and mutated IDH1/2 enzymes and therapy responses. Oncogene. 2018;37:1949–60.

Crispo F, Pietrafesa M, Condelli V, Maddalena F, Bruno G, Piscazzi A, et al. IDH1 Targeting as a new potential option for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treatment—current state and future perspectives. Molecules. 2020;25:3754.

Guo J, Zhang R, Yang Z, Duan Z, Yin D, Zhou Y. Biological roles and therapeutic applications of IDH2 mutations in human cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;0:1344.

Tuval A, Shlush LI. Evolutionary trajectory of leukemic clones and its clinical implications. Haematologica. 2019;104:872–80.

Morita K, Wang F, Jahn K, Hu T, Tanaka T, Sasaki Y, et al. Clonal evolution of acute myeloid leukemia revealed by high-throughput single-cell genomics. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5327.

Cerchione C, Romano A, Daver N, DiNardo C, Jabbour EJ, Konopleva M, et al. IDH1/IDH2 inhibition in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Oncol. 2021;0:345.

M. Gagné L, Boulay K, Topisirovic I, Huot MÉ, Mallette FA. Oncogenic activities of IDH1/2 mutations: from epigenetics to cellular signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2017;27:738–52.

Lo Presti C, Fauvelle F, Jacob MC, Mondet J, Mossuz P. The metabolic reprogramming in acute myeloid leukemia patients depends on their genotype and is a prognostic marker. Blood Adv. 2021;5:156–66.

Chan SM, Thomas D, Corces-Zimmerman MR, Xavy S, Rastogi S, Hong WJ, et al. Isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations induce BCL-2 dependence in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2015;21:178.

Pronier E, Levine RL. IDH1/2 mutations and BCL-2 dependence: an unexpected chink in AML’s armour. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2015;36:229–43.

Chen J, Yang J, Sun X, Wang Z, Cheng X, Lu W, et al. Allosteric inhibitor remotely modulates the conformation of the orthestric pockets in mutant IDH2/ R140Q OPEN. Sci Rep. 2017;7:16458.

Wang F, Travins J, DeLaBarre B, Penard-Lacronique V, Schalm S, Hansen E, et al. Targeted inhibition of mutant IDH2 in leukemia cells induces cellular differentiation. Science. 2013;340:622–6.

Deng G, Shen J, Yin M, McManus J, Mathieu M, Gee P, et al. Selective inhibition of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) via disruption of a metal binding network by an allosteric small molecule. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:762–74.

Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, Fathi AT, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017;130:722–31.

Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Fathi AT, Pollyea DA, Stone RM, Altman JK, et al. Molecular remission and response patterns in patients with mutant-IDH2 acute myeloid leukemia treated with enasidenib. Blood. 2019;133:676–87.

DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Roboz GJ, Altman JK, Mims AS, et al. Durable remissions with ivosidenib in IDH1-mutated relapsed or refractory AML. N. Engl J Med. 2018;378:2386–98. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1716984.

Roboz GJ, DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Mims AS, Prince GT, et al. Ivosidenib induces deep durable remissions in patients with newly diagnosed IDH1-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2020;135:463–71.

Montesinos P, Recher C, Vives S, Zarzycka E, Wang J, Bertani G, et al. AGILE: A global, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study of ivosidenib + azacitidine versus placebo + azacitidine in patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia with an IDH1 mutation. 2022. https://ash.confex.com/ash/2021/webprogram/Paper147805.html. Accessed 11 Apr 2022.

Intlekofer AM, Shih AH, Wang B, Nazir A, Rustenburg AS, Albanese SK, et al. Acquired resistance to IDH inhibition through trans or cis dimer-interface mutations. Nature. 2018;559:125–9.

Quek L, David MD, Kennedy A, Metzner M, Amatangelo M, Shih A, et al. Clonal heterogeneity of acute myeloid leukemia treated with the IDH2 inhibitor Enasidenib. Nat Med. 2018;24:1167.

Choe S, Wang H, DiNardo CD, Stein EM, de Botton S, Roboz GJ, et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating relapse following ivosidenib monotherapy in IDH1-mutant relapsed or refractory AML. Blood Adv. 2020;4:1894.

Wang F, Morita K, DiNardo CD, Furudate K, Tanaka T, Yan Y, et al. Leukemia stemness and co-occurring mutations drive resistance to IDH inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2607.

DiNardo CD, Schuh AC, Stein EM, Montesinos P, Wei AH, Botton Sde, et al. Enasidenib plus azacitidine versus azacitidine alone in patients with newly diagnosed, mutant-IDH2 acute myeloid leukaemia (AG221-AML-005): a single-arm, phase 1b and randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:1597–608.

DiNardo CD, Stein AS, Stein EM, Fathi AT, Frankfurt O, Schuh AC, et al. Mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 inhibitor ivosidenib in combination with azacitidine for newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:57–65.

Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Fathi AT, Mims AS, Pratz KW, Savona MR, et al. Ivosidenib or enasidenib combined with intensive chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed AML: a phase 1 study. Blood. 2021;137:1792–803.

Venugopal S, Maiti A, DiNardo CD, Loghavi S, Daver NG, Kadia TM, et al. Decitabine and venetoclax for IDH1/2-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:E154.

DiNardo CD, Jonas BA, Pullarkat V, Thirman MJ, Garcia JS, Wei AH, et al. Azacitidine and venetoclax in previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl J Med. 2020;383:617–29.

Lachowiez CA, Borthakur G, Loghavi S, Zeng Z, Kadia TM, Masarova L, et al. A phase Ib/II study of ivosidenib with venetoclax +/− azacitidine in IDH1-mutated myeloid malignancies. 2021;39:7012. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO20213915_suppl7012.

Mellinghoff IK, Penas-Prado M, Peters KB, Burris HA, Maher EA, Janku F, et al. Vorasidenib, a dual inhibitor of mutant IDH1/2, in recurrent or progressive glioma; Results of a first-in-human Phase I trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:4491.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SPD and FR wrote the initial and final versions of the manuscript. FR, TK, ND, MK, and CD edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

FR has received funding from Astellas and Novartis and serves as a member on the advisory board for Astellas and Novartis. The authors report no other relevant disclosures.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Desikan, S.P., Daver, N., DiNardo, C. et al. Resistance to targeted therapies: delving into FLT3 and IDH. Blood Cancer J. 12, 91 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00687-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41408-022-00687-5

This article is cited by

-

Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2022)