Introduction

In September 2019, at least twelve African immigrants, most of them from Nigeria, were killed in South African townships after mobsFootnote 1 attacked their shops in Johannesburg and Pretoria.Footnote 2 This was not an isolated case of collective xenophobic violence, but one in a long series of disturbing attacks and brutal killings that had been going on since the end of the 1990s.Footnote 3 Notorious is the incident in September 1998 when two Senegalese and a Mozambican were thrown off a train by a group of people who had been fired up at a rally of the “Unemployed Masses of South Africa” (UMSA), where speakers blamed foreigners for high levels of unemployment, crime, and the spread of AIDS.Footnote 4 According to the African Centre for Migration and Society of the University of Witwatersrand, between 1994 and 2018 there were at least 529 incidents in Johannesburg, which left 309 people dead, over 2,000 shops looted, and more than 100,000 migrants displaced.Footnote 5

Although discrimination towards and violence against migrants, as well as people associated with them, have been documented in South Africa from the end of the nineteenth century onwards,Footnote 6 the number of violent collective outbursts against migrant workers increased considerably after the end of Apartheid and the start of majority rule by the ANC in 1994. Xenophobic mob violence, as a result of migrants being portrayed as a threat to resources, jobs, and safety, also occurred in other parts of Africa, including Ghana, Nigeria, Zambia, Ivory Coast, Kenya, and Zimbabwe.Footnote 7

The South African case is a good starting point for a broader exploration of the causes of mob violence against free labour migrants – both wage workers and self-employed – since the rise of the nation state. In this article, I limit myself predominantly to the North Atlantic region, but I also want to discuss to what extent the mechanisms that we find here may have a larger, global, reach. I follow Tilly's “universalising and variation-finding”Footnote 8 comparative method to help uncover broader mechanisms that allow us to understand under what conditions such mob violence occurs, and what factors prevent it.

Although most research has concentrated on Europe and North America, mob violence against labour migrants is not limited to this part of the world, as the South African case shows. After discussing the North Atlantic experience, I will therefore also look at cases in Africa and Asia as a stepping stone for a more global approach in the future.

Core Question, Concepts, and Theoretical Considerations

I will first define the core concepts used in this article, starting with “mob violence”. This refers to openly displayed physical violence against persons and their possessions (including houses), perpetrated by a group of people that goes beyond a particular intimate face-to-face group of friends or family, and, as a rule of thumb, consists of at least fifty people, who are convinced that their collective violent behaviour is morally justified. “Free labour migrants” are defined as workers and small self-employed entrepreneurs who are born abroad or are internal migrants, perceived as an outgroup, mostly on ethnic/racial/religious grounds, and who migrated voluntarily. Although mob violence can appear to resemble pogrom-like violence against settled minorities, such as Jews or Chinese, including them would dull our analytical razor. The same goes for widening the net to include coerced (and enslaved) migrant labour. Employers and authorities expose them to constant systemic and infrastructural violence,Footnote 9 but they are seldom the target of mob violence, most likely because they are not considered to be competing directly for jobs and housing with native workers.

The core question, then, can be formulated as: What are the historical conditions under which people who consider themselves as belonging to an ingroup can be found to resort to collective violence against free labour migrants? My comparative approach is inspired both by Dik van Arkel's quest to find common factors that explain virulent expressions of antisemitism, and by a recent universalist call from the anthropologist Christoph Antweiler to look for general mechanisms, while rejecting the notion of primitive behaviour.Footnote 10 Like the sociologist Andreas Wimmer, he asks the larger, preliminary question of why, in some cases, ethnic boundaries and group identities are much more entrenched than in other cases.Footnote 11

Explanations for ethnic antagonisms

There are a number of analytical tools and theoretical insights that can help us in our comparative endeavour. The question of why ingroups resent – and, in extreme cases, resort to violence against – labour migrants is not new and has often been cast in terms of ethnic competition for jobs and other resources. Highly influential in this respect is Edna Bonacich's seminal 1972 paper on split labour markets, in which she stresses the importance of direct competition between ethnic groups for the same jobs, often leading to a “split labour market”, in which immigrants accept lower wages and poorer working conditions, resulting in mutual antagonism and violence.Footnote 12 Only when the ingroup is strong enough to resist competition are employers forced to accept the exclusion of foreign workers – as was the case in Australia and other parts of the British Empire after the end of the nineteenth centuryFootnote 13 – or to create a caste system with a privileged position for native workers in a dual labour market setting – as in South Africa under Apartheid, and the Gulf States since the 1960s. Similarly, niche competition can occur when minorities specialize in certain middlemen occupations (traders, brokers, shopkeepers), which may threaten job monopolies employed by dominant groups.Footnote 14 Studying conflicts and violence between ethnic groups in eighty-one American cities between 1880 and 1914, Susan Olzak built on Bonacich's insightsFootnote 15 and concluded that the size and visibility of immigrants largely explains the intensity of conflicts. Violence is likely to occur not so much due to racism, but when dominant groups see themselves forced to compete for the same resources.Footnote 16

As Michael Hechter noted in 1994, the problem with the split labour market theory is that it cannot explain conflicts and violence between ingroups and outgroups in situations where competition is lacking. Moreover, he argues that we should not take ethnic boundaries and categories as given, nor consider resources as finite.Footnote 17 More important for our problematic is that Bonacich more or less takes ethnic boundaries as a given and does not explain how they came about, let alone how boundary maintenance is linked to prevailing negative ideas about certain groups of migrant workers, and ultimately mob violence. These questions are crucial for a long-term analysis and make it necessary to analyse the emergence of ethnic and racial hierarchies and how they impact the construction of membership of communities – both real and imagined.Footnote 18 This may occur at different levels: locally; nationally; or even supranationally, as in the case of the European Union with its common external border regime.Footnote 19 In studying and comparing forms of xenophobiaFootnote 20 against free labour migrants, we can distinguish three different stadia of boundary work.Footnote 21

First, Boundary making: the social construction of group boundaries by implementing a “master status” or inferiorityFootnote 22 of the other, on the basis of religious, ethnic, or social criteria. Such a master status reduces the other to their religion, nationality, “race”, or ethnicity, ignoring all other aspects of a person's identity – irrespective of the context.Footnote 23 The identity of the other is reduced to these primordial and one-dimensional categories in order to align members of the ingroup, especially because their interests often conflict in other domains, such as income and wealth.Footnote 24

Second, Boundary maintenance. Once put in place, these boundaries need to be maintained and guarded by confirming existing inequalities, either by law, or informally, through discrimination on the labour and housing market, and through, inter alia, racial profiling, social distancing, or name calling. Creating different social spheres in the workplace, residential areas, and the public space buttresses the prevailing master status and leads to what Rogers Brubaker has dubbed “groupism”.Footnote 25 Such boundaries often prove resilient and can easily be activated, with “Jews”, “Gypsies”,Footnote 26 and “Blacks” as the most deeply rooted master statuses in the Western hemisphere, and various kinds of caste-like “untouchables” (“Dalit”, “Burakumin”) in India and Japan. The formal boundary maintenance may involve structural physical and psychological violence, as under Apartheid in South Africa, but as long as the outgroup accepts its inferior position as a (regrettable) status quo, mob violence against them will be exceptional. The threat of violence in itself is already highly effective.

Thirdly, Boundary defence: this occurs when the boundary is under threat, or the perceived threat, of eroding. This can occur either because dissenting members of the ingroup start to oppose discrimination, or because members of the outgroup try to blur or shift the boundary, often in combination with opposition from within the ingroup.Footnote 27 In this stage, dominant segments of the ingroup will scale up the boundary maintenance and spread the message that the ingroup is under threat. Crucial for violence to erupt is the role of the state that actually may be unable to guarantee public order, but more often turns a blind eye to vigilantism, or even joins in with or leads the attackers. This may range from lynching individuals and police violence against outgroups,Footnote 28 to murderous mob violence.

This process of boundary work is highly dynamic and often pits different outgroups against each other, as is illustrated by the history of immigration to the United States in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the era of mass migration, European immigrants whose insider status was ambiguous, repeatedly joined collective violence against African Americans in order to demarcate a black–white boundary and thus to emphasize their membership of the ingroup. Also, the “lynching as access card” mechanism forced bystanders, who were afraid to become tarnished by the stigma, to participate or at least not oppose “Judge Lynch”. Lynching thus functioned as a social ritual that affirmed the colour line.Footnote 29 In the words of Beck and Tolnay: “Poor whites, suffering from reduced incomes, perceived neighboring blacks to be competitors for a shrunken economic ‘pie’, as well as a challenge to their superior social station that was ‘guaranteed’ by the caste system.”Footnote 30

Testing the Water: Violence Against Labour Migrants in the North Atlantic Since the Middle Ages

Although the vast secondary literature on the history of migration might suggest that mob violence against labour migrants is predominantly a modern phenomenon, there are good reasons to look at earlier periods as well.Footnote 31 Firstly, we know of xenophobic incidents against labour migrants that occurred in England as early as the Middle Ages, offering us an opportunity to compare with the modern period. Secondly, the period of “thin globalization”Footnote 32 following the opening of sea routes to Asia and Columbus's arrival in the Americas around 1500, created an entirely new opportunity structure for European states to exploit and dehumanize both the Amerindian populations as well as some 12.5 million enslaved Africans. This had long-lasting consequences for the emergence of racial hierarchies and outgroup-making in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean world. For both arguments we have to take a closer look at Europe before the rise of the nation state.

Xenophobia in Europe before the rise of the nation state

In early modern Europe, violence against outgroups occurred frequently, but was mostly limited to social minorities such as Jews, “Gypsies”, “vagrants”, and, later, religious minorities, be they Jewish, Muslim, Protestant, or Catholic.Footnote 33 Few of them were migrants, and they were rarely perceived as a threat to the position of insiders in the labour market. The obsession with religious group identities in early modern Europe may partly explain why antagonism against labour migrants as such remained limited. But more important to explain this scarcity are the following three factors.

First, demographic-economic. Labour migration, both within and between territorial states, was a widespread and systemic feature of early modern societies, within Europe and elsewhere.Footnote 34 Especially those with sought after skills were regarded as an asset to the urban economy, but less skilled workers were often also welcomed, not least because until the nineteenth century urban mortality was so high that cities constantly needed immigrants to maintain their population size, let alone to grow.Footnote 35 Urban elites were well aware that migrants constituted the “linchpin of the urban economy and regulator of urban growth”,Footnote 36 whereas endemic warfare in Europe as a result of state fragmentation after the fall of Charlemagne's empire promoted continuous rural–urban migration and made cities the centres of highly mobile artisanal activity.Footnote 37 Moreover, port cities (like Amsterdam) attracted constant immigrants and trans-immigrants as recruits for the merchant navy.Footnote 38

Second, religious. A second reason why labour migrants were generally not perceived as a threat is the socio-political religious context. Expelled religious minorities such as the Flemish Protestants in the sixteenth century and the Huguenots a century later, were predominantly welcomed and supported by coreligionists.Footnote 39 Moreover, in some states institutional arrangements allowed for religious difference and peaceful coexistence, which explains why most Iberian Jews chose to settle in the Ottoman Empire, with its “millet” system, and others in the “tolerant” Dutch Republic, where Jews and Catholics, although treated as second-rate citizens, were tolerated and protected for economic as well as political-administrative reasons.Footnote 40

Third, political. The absence of national citizenship based on mutually enforceable rights between rulers and ruled constitutes the third pillar of the early modern lack of antagonism against labour migrants. Because societies were highly layered and characterized by structural and ideologically legitimized inequalities, both at the national and the local level,Footnote 41 it was difficult to mobilize nativist sentiments against migrants. The lack of a democratic system explains the absence of political entrepreneurs to serve their populist agenda. Although there was a substrate of protonational feeling,Footnote 42 these seem largely confined to the arts and literature and did not nourish urban inclusion and exclusion mechanisms.Footnote 43 As a result, the fault line between indigenous inhabitants of cities (let alone states) and foreigners was vague at best.Footnote 44 In these “ternary societies”Footnote 45 most urban dwellers, irrespective of their national allegiance, lacked full citizenship and could only gradually and partially become members of urban communities.Footnote 46 Poor relief systems were organized at the urban level, along religious and occupational lines (through guilds), and in the event of unemployment or sickness in parts of Europe (especially England, the Low Countries, and German states) sending communities could be asked to share in the costs or accept their migrated members being repatriated.Footnote 47 Migration was predominantly regulated at the level of cities, not states, and for most urban elites “foreignness” was an undifferentiated category that started beyond the city gates.Footnote 48 Although these observations are all based on the European experience, at first glance the Ottoman, Chinese, and Indian empires seem not to have differed fundamentally in this respect.Footnote 49

These three prophylactic factors may explain the absence of mob violence against labour migrants in most of early modern Europe (and possibly in other continents as well), but not all regions were equally immune. Some regions seem to foreshadow a different national opportunity structure that emerged on a worldwide scale in the nineteenth century. This seems to have been the case especially in the South of England, with London as a hotspot, where collective violence against foreign labour migrants can be traced back to the thirteenth century. The available historiography suggests there are at least eight incidences of mob violence against labour migrants that predate the rise of the modern nation state (Table 1), all of them in England. Further systematic research may render more examples, but crucial for my argument is the fact that they occurred so long before the rise of the nation state, which may help us to better understand the mechanism behind this collective violence.

Table 1. Eight incidents of mob violence against labour migrants in England (thirteenth to eighteenth centuries)

Although, in general, immigrants from the continent were well received in England, a number of conspicuous incidents of violence against “strangers” (especially Flemings and Italians) have been documented. The most well-known is the Peasants Revolt in 1381, by far the most lethal, with the bodies of dozens of murdered foreigners piled up in the streets of London. What seems crucial is the relatively early national demarcation between natives and foreigners, whereby the latter were being accused by English craftsmen, journeymen, and tradesmen of taking their jobs and being favoured by the Crown.

These examples suggest that early state centralization in England – strengthened by its insular geography – stimulated a relatively strong national identity long before the rise of the modern nation state. A pivotal role was played by the Crown, advised by the Privy Council, which could trump the autonomous authority of urban authorities, mostly in London.Footnote 58 Especially the granting of privileges to foreign craftsmen and merchants,Footnote 59 which overruled urban elites, in order to stimulate the national economy, was frowned upon. This strengthened the xenophobic nationalist feelings among English apprentices and merchants, supported by urban authorities. A good example is the complaint of the Lord Mayor of London in 1563, who opposed the liberal immigration regime of Queen Elizabeth because it would lead to native impoverishment and burden the poor relief: “Her majesty subjects […] are eaten out by strangers artificers, to their undoing and our burden and the unnatural hardness to our own country, whereas none of her majesties subjects can be suffered [sic, LL] (be they never so excellent in any art) in their country too live by their work.”Footnote 60

Incidents of mob violence may have been few in number, they nonetheless contain crucial elements of modern violent xenophobia. All occurred in the context of a relatively homogenized state that defined migrant workers, manufacturers, and merchants from other states as “foreign” and “alien”, which stimulated competition for resources along national lines. It is no coincidence that recruitment for the army and the Royal Navy followed this protonationalist pattern, framed as the “great patriotic enterprise”,Footnote 61 based on the Navigation Act of 1651 introduced by Cromwell.Footnote 62 Especially in London, this anti-alien stance concurred with the policy of urban guilds, which excluded foreign artisans and merchants. Thanks to the vigilant measures taken by the urban authorities, serious riots by urban crowds of workers against immigrants were narrowly averted in London in 1563 and in Norwich in 1571.Footnote 63

At the end of the eighteenth century, the nature of mob violence in England converged with the general rise of nationalism, which stressed cultural differences between citizens of different states. Throughout Europe, territorial states became prone to mobilize their subjects along national lines, especially in periods of international tensions, with nationhood (often overlapping with a specific religion) defining the boundary.Footnote 64 A good illustration is the so-called Gordon riots in 1780, when London mobs turned against Catholics in Great Britain, most of whom were seen as being as foreign as the Irish and the French. As a protest against the passing of the “Papist acts” of 1778, meant to reduce discrimination against Catholics (and allow them to join the army), widespread looting and rioting gripped London for days and cost the lives of some 300–700 people, including those of many rioters.Footnote 65

These “Gordon riots” have been interpreted in various ways. A classic Marxist account can be found in George Rudé's famous book The Crowd in History, from 1959, in which he stressed that poverty and economic inequality were the key for many people to revolt. Without arguing that economic factors are irrelevant, however, I think that Rudé too easily dismissed the deeply rooted anti-Catholicism among the urban masses that inspired tens of thousands in London to revolt.Footnote 66 Although predominantly aimed at rich native Catholics and foreign embassies, the poor Irish migrant neighbourhood Moorfields was targeted as well.Footnote 67

Persecuting societies, globalization, and new racial hierarchies

The second reason why the early modern period is crucial to understand mob violence against migrants, including labour migrants, in the past two centuries is the medieval and early modern roots of modern racism and ethnicity. Building on R.I. Moore's Formation of a Persecuting Society, Geraldine Heng has recently argued that the persecution and expulsion of internal religious “enemies” in Europe during the High Middle Ages, especially Jews and Muslims, lay the foundation for the notions of a superior “homo europaeus”.Footnote 68 Religion may have been the dominant category to define outgroups in early modern Europe, but notions of territorialized ethnicity,Footnote 69 race, and blood developed alongside. A good illustration is the suspicion of Jewish and Moorish converts (New Christians) in late medieval Spain. Converted Jews (Marranos) and Muslims (Moriscos) were never accepted as full members of Spanish society, and notions about heredity and genealogy gave rise to an obsession with blood purity (“limpieza de sangre”). This ideology of “blood and faith” was permeated with religion, but unmistakably also contained racist ingredients that would become more entrenched at the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote 70

With the more extensive travels of seafaring Europeans in the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean, these notions, mixed with white Christian superiority, increasingly gained influence and became visible in the new world from the end of the fifteenth century onwards. In the Atlantic, the main outgroups were enslaved African (forced) migrants and the native Amerindian population. Their dehumanization legitimized the system of land grabbing, and slavery enabled the plantation system and other forms of coerced labour.Footnote 71 At first the Spanish and Portuguese tried to compel the indigenous population of South America to work under a system of encomiendas. Where this failed, especially in the Caribbean, native people were killed or expelled from their land, which was transformed into a “terra nullius”, populated by enslaved Africans.

Structural violence against slaves was applied to prevent them from running away and establishing marron communities in impenetrable uphill regions, or reaching the territory of competing empires.Footnote 72 This plantation system with imported coerced labour was found in its most intensive form in the Caribbean, Brazil, and later on in the southern part of the United States. In South and Southeast Asia, as well as in South Africa, Europeans followed similar strategies, forcing millions of African and Asian people to move and work.Footnote 73

The ideas that legitimized slavery are highly relevant to understand how ethnic and racial boundaries forged xenophobic notions antithetical to free labour migrants in the modern era. From the end of the eighteenth century, until then partially fluid categories in overseas regions became petrified and chiselled in scientifically approved racial hierarchies, resulting in structural discrimination of former slaves and their descendants in the Americas, Brazil, and South Africa.Footnote 74 Furthermore, racist ideas motivated the exclusion of Chinese and other Asian workers from the Western hemisphere from the 1880s onwards.Footnote 75 Finally, racist notions about Africans were used to stigmatize Irish and “swarthy” eastern and southern Europeans migrants in mid-nineteenth century North America.Footnote 76

Mob Violence in the Era of Nation States

In the nineteenth century, these two early modern developments – the proto formation of nationhood and its concomitant xenophobia, and the developing racial hierarchies following the rise of the “homo europaeus” – merged in the format and ideology of the nation state, based on direct rule and the ideal of ethnically homogenous populations, with citizenship regimes shifting from the level of cities to that of states.Footnote 77 The concomitant belief in hierarchically structured human races with “whites” at the top and “blacks” at the bottom became widely accepted in science and society, and legitimized the colonization policies of states like Great Britain, France, Portugal, the Netherlands, and Japan. The countermovement, inspired by the principles of brotherhood and equality of the French Revolution, led to the rise of socialism and the abolition of slavery and proved strong as well. But with the outbreak of World War I in 1914, international solidarity encountered the bounded membership regime of nation states, which prioritized rights and resources of its own citizens.

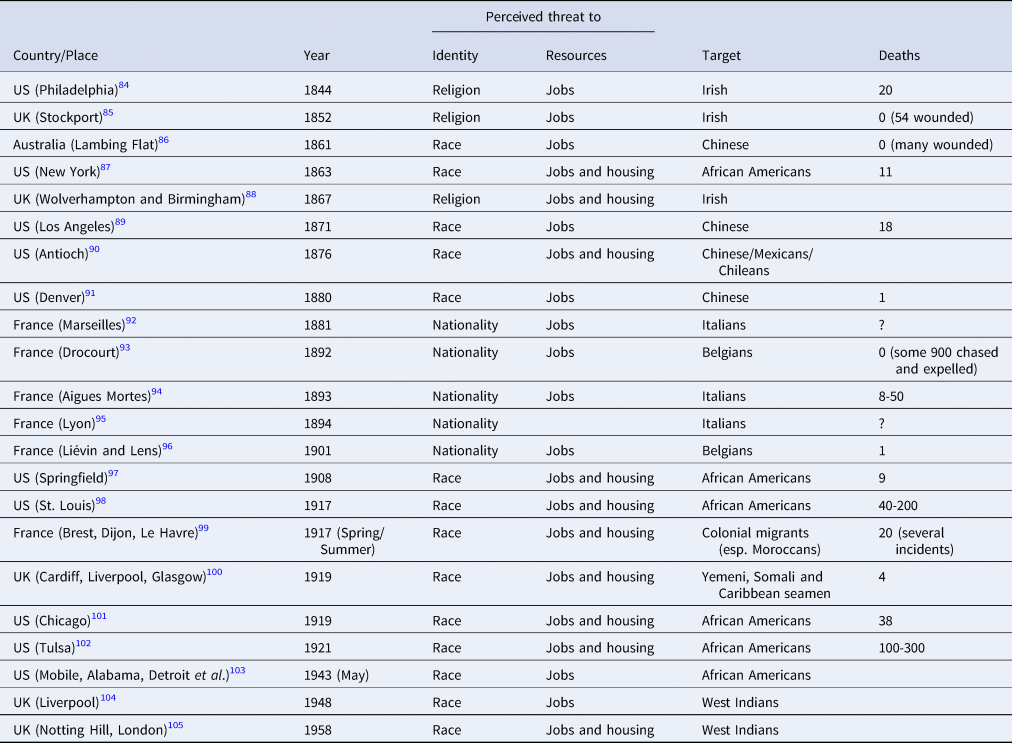

To map the extent of xenophobic mob violence against free labour migrants (both internal and international) in the modern era I have undertaken a search through the secondary literature. Although far from complete, the results in Table 2 suggest that this type of violence largely overlaps with what has been called the first round of modern globalization, starting in the 1820s, but really getting underway with the transport revolution – steamships and trains – in the mid-nineteenth century.Footnote 78 As Adam McKeown has demonstrated, globalization did not end with World War I, but extended in large parts of Asia and Latin America well into the 1930s.Footnote 79 Finally, it also concurs with the “Great Migration” of African Americans and poor whites from the south of the United States to the west and the north of the United States, starting in World War I.Footnote 80 After World War II the number of incidents quickly decreased and became less lethal, only to reappear since the 1990s, especially after regime changes in Russia and South Africa, to which I will return later.

Table 2. Most infamous recorded incidents of collective xenophobic violence against (internal and foreign) labour migrants in the North Atlantic world (1844–1958)

Although far from exhaustive, a common thread is that, in all cases listed here, violence was motivated by a mix of perceived cultural (identity) and socio-economic (resources) threats to the position and status of members of the ingroup who considered themselves superior and more deserving.Footnote 81

In the North Atlantic, the outgroup varied from African Americans and Chinese, to West Indians, Italians, and Irish migrant workers.Footnote 82 They were almost invariably accused of working for too low wages and accepting subhuman (“coolie”) conditions. Often, protests were framed in an anti-capitalist, pro-worker discourse, as in the Denver anti-Chinese riot of 1880, which became part of the Democratic campaign that accused Republicans of deliberately importing Chinese labour to weaken the (“white”) working class.Footnote 83 Such racial connotations were not limited to labour migrants from Asia or those with African roots. Irish and Italians, too, were often framed as racially inferior.Footnote 106

That anti-black sentiment became especially virulent in postbellum United States need not come as surprise, because from then on African Americans gradually became more mobile and started to work as free wage labourers. The presence of black Americans in similar sectors and occupations as whites was perceived by the latter as an insult and threat to their racial self-esteem. Violence against African Americans was used to restore the colour line and to diminish direct competition between blacks and whites. Especially the issue of miscegenation aroused violent sentiment and was the source of most lynchings.Footnote 107

In Europe, Irish and Italian labour migrants were also confronted with mob violence.Footnote 108 Although accusations of wage debasement and breaking strikes were recurrent elements, as in the United States these labour migrants were primarily considered a threat to the status and core identity of the native worker ingroup. When in the course of the twentieth century Italian and Irish migrants gradually “became white”,Footnote 109 mob violence in North America and Western Europe increasingly targeted Mexican, Asian (Chinese sailors),Footnote 110 and African labour migrants, and racialized internal migrants such as Afro-Americans in the US and Roma in Europe. This shift is mirrored in the racial hierarchy of France's leading demographer in the interwar period, George Mauco, who drew the line between Europeans and migrants from African and Asian colonies.Footnote 111 In Great Britain, we find similar colonial stereotypes, which motivated various attacks on African and West Indian sailors in Cardiff and Liverpool in June 1919. Although the number of fatal casualties was limited, it created an atmosphere of terror, well described by a young sailor who arrived shortly after the riots: “Suddenly you couldn't go out. White people in groups started roaming and anytime they saw a black man: ‘There's a nigger, get him! Get him!’ They used to come from all over to hunt black people to beat them up. It became a bit of fun for them.”Footnote 112

Mob violence against labour migrants in Africa and Asia

Although most examples of mob violence against labour migrants in the literature come from the North Atlantic, the more recent outbursts in South Africa show that this phenomenon is not an exclusively Western one. Two earlier examples make clear that a similar ingroup–outgroup mechanism may be at work in other continents, although further research is needed to find out whether this also holds for other cases. The first case regards Indian labour migrants in interwar Burma. Technically, they were internal migrants, but due to their ethnicity and religion (partly Hindu, partly Muslim) they were considered an inferior and threatening outgroup by the native (Buddhist) Burmese population. In 1930 and 1938, this led to widespread organized attacks on Indian workers, who were accused of unfair competition in the labour market, but also of imposing their religion and culture on the native Buddhist Burmese.Footnote 113 Furthermore, Muslims especially were targeted, because nationalists regarded them as an existential threat to Burmese nationhood, not in the least because a number of them married Burmese women.Footnote 114 The violent outbursts cost the lives of hundreds of Indian workers, predominantly Muslims.Footnote 115

The second case at first sight seems an outlier in the sense that the violence was much more encouraged from above.Footnote 116 The mass killing of Korean migrants in Japan in 1923 started after false rumours (not contradicted by the government) were spread about Korean labour migrants immediately after the earthquake in the Kantō region of Tokyo that killed between 100,000 and 140,000 people. Koreans, a small minority of some 20,000 migrants, were accused of using the occasion to plunder and rob people, and poison the well water as part of a revolt against the Japanese state.Footnote 117 To suppress this putative uprising, the state mobilized the police and soldiers under martial law and allowed vigilantes to participate in the murderous violence that eventually cost 6,000 Koreans their lives.Footnote 118 The main explanation for this bloodbath is the impenetrable boundary between those who were considered Japanese and those who were outsiders, who could never acquire membership. Or, as explained by Sonia Ryang:

This pseudo- or fictive-blood myth as a national origin is important, as it works to eternally and completely exclude anyone who cannot claim their descendancy from the Sun Goddess from membership to the people called Japanese, that is, the eternal banishment of the non-Japanese. Japan's case, thus, is a classic case of the national sovereignty granted to individuals according to their birth into that nation. To this day, its nationality law, along with that of Germany's, bases its principle on jus sanguinis, that of blood.Footnote 119

Apparently, the chaos and panic ignited a widespread fear of the breakdown of the boundary between Japanese and foreigners and Koreans taking over. As members of the outgroup they did not belong to the political orderFootnote 120 and were considered outcasts, unworthy of basic human rights. This mass murder in 1923 may seem extreme in its extent and cruelty, but it mirrors the ground rules of mob violence against labour migrants in the North Atlantic; the only exception being that in this case the state actively supported the violence.

The rise of universal human rights and the welfare state

Initially, the immediate post-war years seemed a continuation of the pre-war situation. A telling example was the “race riots” in Liverpool in August 1948. During the war thousands of “black” workers had been drawn from British colonies in the Caribbean and Africa to man Britain's navy and vital economic sectors, but as soon as the war was over the National Union of Seamen demanded that “coloured” seafarers be vetoed entrance to the country and those present be expelled. In this atmosphere large crowds attacked houses and restaurants frequented by black seamen.Footnote 121

These temporary guests were soon joined by large numbers of postcolonial immigrants from the West and East Indies who came to stay. On arrival, most of them became citizens, at least formally,Footnote 122 which created tensions in the cities and neighbourhoods where they settled down. Small-scale riots flared up and in the 1960s conservative politicians like Enoch Powell consciously mobilized the racism within working-class neighbourhoods. His infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech in 1968, in which he predicted that: “In this country in fifteen or twenty years’ time the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”, shows that colonial racism was far from dead.Footnote 123

The highly incendiary language of Powell and others fuelled racism and discrimination, but did not debouch into mob violence in general or against labour migrants in particular. An important prophylactic factor, especially in Europe, was the ponderous memory of the Holocaust, the rise of a human rights regime, and the ideology of equality.Footnote 124 Together with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, this gave rise to what we could call an “ethical revolution”, defined as the broadly shared conviction that all kinds of discrimination and stigmatization should be banned.Footnote 125

A second crucial factor that explains the decrease and fading of mob violence in Europe is the inclusion of labour migrants in fully fledged welfare states, which erased wage differences for the same jobs, while channelling migrant workers into lower segments of the labour market where competition with native workers was limited. This new regime explains the decline of mob violence against labour migrants in the North Atlantic, while conversely its absence laid the foundation of new riots elsewhere. Most conspicuous is the shift to Africa, Asia, and Russia after regime changes at the end of the twentieth century, where a mix of nationalism and lack of state welfare has generated similar tensions between ingroups and outgroups and where migrants became a direct competitor for resources to native workers. The long list of cases of xenophobic violence against foreign migrants in Africa, especially South Africa,Footnote 126 and in RussiaFootnote 127 since the 1990s testifies to this shift.

Hitherto undiscussed are middlemen minorities (migrants as well as their descendants) such as the Chinese in Southeast Asia (especially in Indonesia) and the Caribbean.Footnote 128 Due to their concentration in self-employment, they are perceived less as a threat to jobs and housing, and resented more for exploiting their semi-monopoly position by raising prices of basic foods and, in some cases, discriminating against other outgroup minorities, including African Americans – ingredients that fuelled the 1992 Los Angeles riots against Korean shopkeepers.Footnote 129

Barriers to mob violence and their erosion

Notwithstanding the ubiquity of migration in the globalizing world, xenophobic mob violence is more the exception than the rule. This does not mean that migrants are treated as equals or seen as unproblematic. Lower-skilled migrants especially are often discriminated against and excluded from all kinds of social rights and citizenship, both internal (China, within the European Union)Footnote 130 and internationally. The difference is that the infrastructural violence they encounter is not produced by the enraged native population, as in South African townships, but by employers and state officials (police, border guards).Footnote 131 Collective mob violence is especially rare in autocratic polities, where migrants are firmly locked into a secondary segment with few rights. A well-known example is the strict segregation under Apartheid and under Jim Crow legislation, or the Bracero system in the United States.Footnote 132 And, more recently, the labour market apartheid in Gulf states like Qatar, where, currently, eighty-eight per cent of the total population (2.8 million) are migrants, most of them from South Asia. In all these cases, the “autochthonous” minority is so powerful and privileged that there are no grounds for xenophobic mob violence.Footnote 133 It is exactly this highly segmented vulnerable semi-rightless position that explains the absence of collective violence, because the ingroup is shielded from competition. Breaches in the wall that separates such segregated labour markets, however, often immediately lead to reactions from the privileged group.

This happened regularly in South Africa, where employers, especially in the mining sector, at times tried to incite white and black workers against each other. A telling example is the “Rand Revolt” in 1922. Initially, it was fought among white workers, some of whom refused to join the strike. Black workers, whom the mine owners used to break the strike, were initially ignored and not seen as “scabs”, simply because they were not considered as belonging to the community of labour, which was perceived by definition as “white”. Only after two months, when the strike failed, was violence directed at blacks, who were indiscriminately hunted in the Johannesburg suburb of Vredeburg, whereas others attacked compounds of black workers. According to Jeremy Krikler: “It might be seen as displaced violence: a terrifying assertion of supremacy over the symbolic (black) enemy at the moment when it became clear that the infinitely more formidable white enemy had defeated the rebels. For there appears to have been a spate of racial killings in Johannesburg at the very moment of defeat.”Footnote 134

A more positive prophylactic institutional arrangement is states that combine open or regulated access for labour migrants with inclusive welfare arrangements and a principal anti-discriminatory stance. Most early modern cities, as well as welfare states during the “Trente Glorieuses”, to a large extent meet this criterion, distinguishing admittedly between citizens and foreigners, but offering clear pathways for gradual inclusion. Since the 1980s, this inclusive welfare model, in which labour migrants – supported by civil society organizations – have (or can successfully claim) social and residency rights, has been under attack.Footnote 135 When, in the course of the 1980s, the welfare state was challenged by the rise of neoliberal fiscal and social policies, ingroups increasingly felt threatened, especially when xenophobic politicians became successful in obscuring the root causes of the growing social inequality and in blaming immigrants for the erosion of the social contract. This new global ideological opportunity structure stimulated what has more recently been termed “welfare chauvinism”: the conviction among the native working class that the nation state should protect its own (national/white) members when it comes to access to jobs, social housing, and welfare. Part of the ingroup is drawn to radical right populist anti-immigration parties, which mobilized this discontent and played in to what Lipset called “working class authoritarianism”.Footnote 136 Yet, as Crepaz in his comparison of welfare and migration policies in the United States and Western Europe has shown, this anti-immigrant stance can be contained and the more comprehensive the welfare states are, the more tolerant natives tend to be of immigrants.Footnote 137 That this development has seldom led to mob violence against labour migrants is furthermore due to the upholding of the monopoly of violence by the state.Footnote 138

Conclusion

To what extent does the tour d'horizon of mob violence against labour migrants in the North Atlantic, and our brief exploration of cases in Asia, help us to understand under what conditions people who regard themselves as natives (or aspire to belong to the ingroup) resort to collective violence against free labour migrants? And to what extent can the insights derived from North America and Western Europe have a broader (more global) explanatory power? Before we return to the South African case that we started our journey with, let us first summarize the most important mechanisms behind the cases that have been listed in this article.

The first conclusion is that scholars like Edna Bonacich and others were right in pointing to competition for resources between natives and migrants as an important cause of violent xenophobia. What is largely missing in her analysis, however, is the preliminary question of how group boundaries came about and how they helped to legitimate exclusion. In other words, she assumed too easily that this kind of violence is closely linked to the rise of the nation state, which defined those outside the idealized homogenous core group (largely defined in ethnic or racial terms). Only in early modern England did this boundary-making process start earlier, with a key role for the Crown.

Once in place, such boundaries need maintenance, through discourse, legislation, and surveillance. Migrants defined as outsiders who did not accept their inferior role and thus became direct competitors for key resources such as jobs and houses were bound to evoke irritation, protest, and in extreme cases mob violence. The latter occurred a number of times in early modern England, but such incidents were especially visible in the period 1860–1880 (US and Australia), 1880–1900 (Western Europe), and on both sides of the Atlantic around World War I.

In all these cases, boundary making (through heightened nationalism, imperialism, and embedded racial hierarchies) was prominent, while at the same time the state was unable or unwilling to protect its citizens against competition on the labour market and to provide a welfare safety net. This lack of actual boundary maintenance and thus a glaring contrast between ideology and practice could lead to major tensions, and in some cases to mob violence – especially when the authorities were unwilling or unable to intervene. Moreover, it is striking that violence was especially directed against outsiders who were considered racially or culturally inferior, such as the Chinese and African American internal migrants in the United States and colonial migrants in the United Kingdom. But racialized Italians and Irish labour migrants could, too, become a target.

These cases of boundary defence decreased from the 1930s onwards in the North Atlantic. This can be explained by a mix of factors. First, the rise of welfare arrangements since World War I reduced the risks of unemployment and sickness and made direct competition less threatening. Second, Asian workers, especially Chinese, were largely excluded from the Atlantic (as well as from the western offshoots in Oceania). Third, part of the racialized others who were allowed in by the state were channelled into specific (secondary) segments of the labour market and moreover treated as temporary workers. Examples here include the Bracero programme for Mexicans in the United States (1942–1964) and guest worker schemes in Western Europe, which functioned as a segmented way of boundary maintenance.

New tensions arose in Western Europe when, in the era of decolonization after World War II, immigration from colonies or former colonies in the Caribbean, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Africa to the various “metropoles” took off. Mob violence was limited and largely averted due to the intervention of urban police forces that upheld the monopoly of violence, but also because states deliberately framed some of these newcomers as “belonging”. Hence the term “repatriates” for ethnically mixed migrants from the former Dutch East Indies, most of whom had never been in the Netherlands. Furthermore, the extensive welfare system and various forms of labour (and housing) market segmentation shielded insiders from direct competition for resources. And, finally, the 1960s were the era of an ethical revolution, when the ideal of equality crowded out racist and discriminatory discourses, giving rise to a period of “integration optimism” that lasted until the late 1980s.Footnote 139

These prophylactic barriers were largely missing in the South African case that this article began with. Although the post-Apartheid South African state clearly created a hierarchical boundary between its citizens and foreigners and moreover raised great expectations in the form of a social welfare contract, these promises were not kept.Footnote 140 At the same time, while stigmatizing foreign workers the state refused to maintain the boundary and created a situation of direct competition for jobs and houses. Furthermore, the state left the ensuing boundary defence to the population in the townships and thus largely relinquished the monopoly on violence.Footnote 141 This example calls for a more global comparison, which may show whether this recipe for mob violence against free labour migrants also worked outside the North Atlantic and former colonized parts of the world.