-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Lucy Parker, Rosie Maxton, Archiving Faith: Record-Keeping and Catholic Community Formation in Eighteenth-Century Mesopotamia, Past & Present, Volume 257, Issue 1, November 2022, Pages 89–133, https://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtab037

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

This article investigates the archiving practices of a little-known group of Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, the Diyarbakır Chaldeans, in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It argues for a flexible definition of archives, based not on traditional characteristics such as links to a defined institutional repository, but on their purpose of community formation. The loose institutional structure of the Chaldean Church resulted in an unconventional archive, which never had one physical centre and consisted largely of liturgical manuscripts; nonetheless, it recorded recognizably archival material and gained cohesion from the overlapping circles of families, scribes and churches involved in its production, as well as from systematic innovations in scribal practices. The Diyarbakır Chaldean archive not only reflected the distinctive form of the community but also contributed to creating and reshaping it. By recording social ties, it kept these obligations alive for decades and generated ongoing commitments. It also imagined the community on an illusory level, occluding tensions and troubles in order to preserve an idealized image of a church united under pious leadership. This dispersed, mobile archive thus was intimately connected to community formation and contributed to the survival of the Chaldean Church in a time of immense difficulty.

In the early eighteenth century, a priest in the village of ʿAyn Tannūr, near the city of Diyarbakır in the south-eastern Ottoman Empire, produced an exceptional manuscript.1 In this manuscript, the priest, ʿAbd al-Aḥad son of Garabed, wrote a hagiographic Life of the first patriarch of his recently established Chaldean Catholic Church, Yawsep I (d. 1707).2 ʿAbd al-Aḥad depicts Yawsep as a ‘living martyr’ for Catholicism, who had banished the darkness of heresy and brought light to his followers.3 The Life is highly idealized, and although ʿAbd al-Aḥad was a contemporary and disciple of Yawsep, it is largely depersonalized: ʿAbd al-Aḥad erases himself from the narrative, barely referring to his own involvement in the events described.4 Elsewhere in the manuscript, however, he records intensely personal information about his own life. He provides a lively account of the mishaps and adventures that he experienced on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1707.5 He also describes a plague that afflicted his village in 1712, claiming the lives of his wife and three of his children; he himself survived, but was still unwell and leaning on a stick when he buried his family members.6

This manuscript is of manifold historical interest. Perhaps most obviously, it has great potential to illuminate the growth of Catholicism in the eastern Ottoman Empire. It provides an insight into religion and society in early eighteenth-century Diyarbakır and its neighbouring villages. Few studies have focused on the Diyarbakır region in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.7 Nonetheless, it was an area of considerable strategic importance to the Ottoman state, because of its proximity to the border with the Safavid Empire.8 In political terms, Kurdish tribes and notables wielded considerable influence in the region, often within the framework of Ottoman administration, but sometimes in tension with it.9 Diyarbakır had a very diverse population, including Christians of various confessions (Armenians, Syrian Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, and the so-called ‘Nestorian’ Church of the East) as well as Jews and Yezidis.10 Firm population numbers are lacking, but some estimates suggest that non-Muslims outnumbered Muslims at some dates in the early modern era.11 Languages spoken included Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic, Persian, Armenian and various Neo-Aramaic dialects; the Church of the East and the Syrian Orthodox still also used Syriac as a written and liturgical language.12

Catholicism was relatively new to the region.13 The sixteenth century had witnessed a union between the Catholic Church and a breakaway part of the Church of the East, under the patriarch Yōḥannan Sūlaqā, who had been confirmed as patriarch by Pope Julius III in 1553 and had established the seat of his new church in Diyarbakır. In 1555, however, Sūlaqā was put to death by a Muslim governor, allegedly at the behest of Christian rivals.14 Union between Sūlaqā’s successors and the Catholic Church continued for some generations, but in the early seventeenth century this patriarchal line relocated further east and the connection to Rome lapsed.15 By the late seventeenth century, in part due to European missionary work, Catholicism had begun to win converts from various Christian communities in the area. Yawsep I, the subject of ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s biography in CCM 12, had been a bishop in the Church of the East until his conversion to Catholicism; in 1681, he was officially confirmed by Innocent XI as patriarch of the new Chaldean Church (Chaldean being the term commonly applied to Catholics from the Church of the East tradition).16 ʿAbd al-Aḥad himself seems to have been a disciple of Yawsep, and was a member of the highest Chaldean echelons; in 1714, he was appointed metropolitan bishop of Diyarbakır by Yawsep’s successor Yawsep III.17 CCM 12 thus offers exceptional insights into this early phase of Catholicism in Ottoman Mesopotamia.

Early modern Catholicism is now fully recognized as a global movement.18 Scholarship on the Catholic expansion into Asia and the Americas has proliferated, but the focus tends to be on the European missionary orders, largely due to an apparent dearth of source material in indigenous non-European languages. Because of this, even the most sophisticated collections on Catholic missions often lack local perspectives.19 The Christians of the Ottoman Empire merit special consideration in this discussion. Western Catholic interactions with the various Christian communities of the Middle East (usually labelled together with the broad-brush term ‘Eastern Christians’) have sometimes been neglected in these debates, despite important studies by Eastern Christian specialists on these contacts.20 But the growth of Catholicism in the Middle East has the potential to move historians’ study beyond missionaries, in two main ways. First, compared to other fields of global Christianity, Eastern Christianity is relatively rich in texts surviving in indigenous languages (most commonly Arabic, sometimes Syriac and Armenian). Second, because, unlike in most other mission fields, the Middle East had a rich pre-existing tradition of Christianity, the missionaries (who primarily targeted Eastern Christians rather than Muslims or Jews) played a rather different role.21 Missionaries were often important in the foundation of Catholic churches in the Middle East; ʿAbd al-Aḥad records, for instance, that Yawsep I was converted to Catholicism by Capuchins in Diyarbakır.22 But because these Catholic converts had already been Christians, they had extensive local resources to draw upon, from biblical manuscripts to clergy. Local Catholicism was thus less dependent on missionary involvement than in some areas, and at times, particularly in more remote parts of the Ottoman East, Eastern Catholics sustained themselves with little missionary intervention.23 The Middle Eastern Churches thus provide an opportunity to write a history of extra-European Catholicism beyond missionaries.

Scholars have recently lamented that, in comparison to the study of the missionaries, far less work has considered developments after missionaries withdrew and local clergies took over, and, more fundamentally, that scholarship on ‘global Catholicism’ is almost entirely separate from that on Catholicism within Europe.24 The former is predominantly focused on the missions and on processes of evangelization and accommodation; the latter has investigated a range of questions about local religion, reform and the implementation of the Council of Trent, and, more recently, lay piety and practices of archiving.25 This historiographical division means that our understanding of these latter questions derives solely from the European context, thereby underestimating the diversity of the early modern Catholic experience. This creates a misleading boundary between European and non-European Catholicism, as if this loose geographical criterion was the critical divide in Catholic experiences, even though both areas had vast divergences within them. Little work has compared Catholic experiences in Europe and globally.26 By asking these questions typically applied to European Catholicism about Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, we hope to diversify understandings of what it meant to be Catholic in this period, and to break down this artificial barrier between the two dominant historiographies within the field.

ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s manuscript, CCM 12, provides a window into this. His inclusion of very personal information in the same manuscript in which he provides an idealized, polemical narrative of the founding of his new church raises questions about record-keeping and the formation of a local Catholic identity. Scholars of European Catholicism have recently, in the wake of the ‘archival turn’, rethought approaches to record-keeping, arguing for more flexible definitions of archives which can encompass processes beyond formal institutional records, and which enable comparison across geographical boundaries.27 The divide between ‘public’ and ‘private’ archives has also been convincingly challenged.28 Our work adds to these calls for a radical rethinking of the early modern archive, one that will enable the integration of extra-European Catholic communities into the discussion. Manuscript culture need not be excluded from definitions of archival practices. In many ways, CCM 12 functioned as a mini-archive in itself: ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s descendants used it to record further information about their family across the decades.

But CCM 12 can only be fully understood when considered in relation to a broader set of manuscripts, now scattered across the globe, in which members of ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s family and Church recorded various kinds of information about their community. These manuscripts, although they never had one fixed physical location, moving between local churches and family ownership, should be read together, as a disparate and mobile archive; seemingly random pieces of information recorded in individual texts gain coherence only when viewed in relation to other manuscripts in this group.29 The archive derived its unity not from a relationship to one physical location or institution; rather, its cohesion comes from shared scribal practices, from the relatively small group involved in its creation, and from its usage, passing between ‘private’ and ‘public’ ownership according to the shifting needs of the community. We thus argue for a definition of archives focused less on physical and institutional characteristics than on their purpose: preserving information about a group over time, in part with the intention of solidifying that group’s identity and community resolve.

Understanding the archive provides a new perspective on local Catholic communities. The archive did not simply reflect the shape of the Chaldean community; rather, it created and imagined the community.30 We could speak here of the agency of the archive, which had influence beyond the personal power of any individual who contributed to it. Donations and dedications of manuscripts helped to solidify loyalties within the community; the archive kept social ties alive for decades. The archive also, however, imagined the community in a more illusory fashion. We know from material in Western repositories that the Chaldeans faced considerable challenges in this period, from debts to absentee patriarchs. These challenges barely feature, however, in the Eastern manuscript archive, which is focused on successes: absent patriarchs are recorded as if present; debts are noted only if resolved. While the archive created real bonds in the community, it simultaneously transformed the community into an imagined, idealized church, when the reality was more complex and problematic. This very process of idealization in turn contributed to communal solidarities.

The Chaldean Catholic Church in the eighteenth century was recently established, small, and vulnerable to threats from rival Christians and from Muslim governors. Divisions within it were so considerable — in particular, as we will see, the patriarchs based in Diyarbakır struggled to extend their authority over Chaldeans in Mosul — that arguably we should speak not of the Chaldeans as a whole, but of the Diyarbakır Chaldeans. They thus represent a highly marginal group of early modern Catholics. Nonetheless, they have much to offer to understandings of early modern Catholicism. It is becoming increasingly apparent that global Catholicism was a compilation of many exceptions, rather than one typical Catholic experience.31 The Diyarbakır Chaldeans offer the opportunity to challenge the historiographical divide between extra-European and European Catholicisms, showing that it is possible and productive to ask the same questions about both. Secondly, they can contribute to a rethinking of early modern Catholic archives, one which focuses not on formal characteristics but on usage and purpose, thereby enabling comparison across geographical borders. Thirdly, they offer a new perspective on local Catholic identity formation, showing its deep entanglement with textual practices. Finally, we hope to demonstrate how an atypical microhistory ‘on the margins’, on the borders of a phenomenon, in this case early modern Catholicism, can contribute to our understanding of a much bigger picture.32

I CCM 12: AN UNCONVENTIONAL ARCHIVE

The exceptional manuscript CCM 12 serves as a window into the Chaldean record-keeping project as a whole. Its diverse contents, as well as the numerous paratextual notes added to it over more than a century, justify labelling this manuscript as an archive in its own right. It cannot be characterized as either public or private, seamlessly shifting its focus between individuals, families and communities. It sheds light on the close relationship between scribal culture and archiving, which has been demonstrated for other early modern settings.33 CCM 12 was not a manuscript frozen in time but a living archive, which Chaldeans across the years used to document important events in their personal and community histories.

The manuscript was copied by ʿAbd al-Aḥad son of Garabed in several stages from about 1705 to 1719. It spanned different phases of his career, from priest to bishop: in 1714 Patriarch Yawsep III appointed him as metropolitan of Diyarbakır, under the episcopal name Basileos, effectively designating him second-in-command of the Chaldean Church.34 Interestingly, the order of texts in the manuscript does not reflect their chronological sequence: ʿAbd al-Aḥad appears first to have copied various didactic texts including Marian miracle stories (items 3–4), before adding at the start of the manuscript two personal accounts of pilgrimage and plague (items 1–2), and returning to add the Life of Yawsep I (item 7).35

Contents of CCM 12 [Texts copied by ʿAbd al-Aḥad; notes added by other scribes]

fo. 1r. Ownership and other later notes.

fos. 1v–9r. Account of pilgrimage by ʿAbd al-Aḥad to Jerusalem in 1707–8.

fos. 9v–10r. Plague account 1712.

fos. 10v–171v. Miracle stories and letters of Mary. Includes other assorted sermons, proverbs and miracles.

fos. 172r–241r. Book of the Student (didactic Christian text). Completed May 22nd 1705.

fos. 241v–264v. Parables, Carmelite texts.

fos. 264v–273r. Commentary on the Rosary.

fos. 273v–291r. Life of Yawsep I. Completed May 22nd 1719.

fos. 291v–292v. Syriac poems in praise of the pope and the Roman church.

fo. 293r. Plague account 1771.

fo. 293v. Ownership and other notes.

The most well-known text in the manuscript, ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s Life of Yawsep I, has until now only been known to scholarship in modern translations, so the discovery of the autograph manuscript is of great significance.36 The Life represents the main source for the founding of the Chaldean Church in Mesopotamia in 1681. As it reports, a bishop of Diyarbakır, Yawsep, converted from the Church of the East (the so-called ‘Nestorian’ church, deemed heretical by Catholics) to Catholicism in the late seventeenth century after contacts with Capuchin missionaries. He was officially confirmed by Innocent XI in 1681 as patriarch of the new Chaldean Church.37 ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s Life of Yawsep extols Yawsep’s efforts to defend the Catholic faith with traditional hagiographical tropes, including vivid accounts of his suffering and salvation through heavenly miracles.38 As well as promoting Yawsep as a saintly individual, the Life is equally concerned with identity construction for the new Chaldean Church, expressing systematic rejection of the Church of the East from which it had seceded. ʿAbd al-Aḥad notably attacks the Church of the East for their veneration of the fifth-century patriarch Nestorius, who was condemned as heretical by Catholics for dividing the humanity and divinity in Christ and for refusing to call Mary ‘Mother of God’.39 He compares the followers of Nestorius to ‘vicious foxes’ who had ‘sowed tares in the field of the Church’, calling their doctrine ‘black, decaying smoke from the depths of Hell’.40 He is keen to demonstrate the Chaldeans’ perfect Catholic orthodoxy in belief and practice; he venerates the pope, refers to Mary as ‘Mother of God’, and even describes the Chaldeans using communion wafer moulds sent from Rome.41

His goal of promoting Chaldean Catholic orthodoxy is also revealed in other texts in the manuscript, despite their diverse literary genres: a collection of Marian miracles, which includes stories explaining doctrines such as purgatory;42 didactic treatises about the Carmelites, probably based on an Italian missionary’s original;43 and Syriac poems in praise of the pope, used by ʿAbd al-Aḥad to claim that earlier East Syrians shared the Chaldeans’ support for the papacy.44 The manuscript thus serves as a record of the history, growth and teachings of the Chaldean community.

Not all of the material in CCM 12 is of this formal nature, however. The manuscript also contains a much more personal text: an autobiographical account by ʿAbd al-Aḥad of his pilgrimage from his village of ʿAyn Tannūr to Jerusalem in 1707–8, which abounds in personal reflections and emotionally charged anecdotes.45 He describes the intense seasickness he experienced on the journey, the fatigue caused by the heavy vestments he wore during Easter celebrations in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and his disgust at the behaviour of other pilgrims during these celebrations.46 In contrast to the community-building focus of the other texts in the manuscript, ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s travelogue documents his individual piety, inscribing his presence at famous Christian sites, and memorializing an arduous trip propelled by his own devotion. This shifting focus between the individual and the collective supports scholarly calls to move beyond binary understandings of ‘public’ and ‘private’ archives.

The rich body of paratexts that frame CCM 12 also represent a fundamental element of its living archive. Some of these notes are lengthy, and challenge the boundary between ‘text’ and ‘paratext’.47 After his travelogue, ʿAbd al-Aḥad wrote an account of a plague that struck the Diyarbakır region in 1712.48 The first-person narrative begins by recording the losses suffered within ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s immediate family: his wife Eriskīn, his children Marta, Rifqa and Qūryāqūs, and several of his nieces and nephews. ʿAbd al-Aḥad provides poignant personal reflections, commenting, for example, that his brother Hormizd did not speak for fifteen days after his children died. The account then moves to the wider Chaldean community in ʿAyn Tannūr, quantifying losses of individuals and households in the village, before finally listing Chaldean victims across the entire Diyarbakır region, including prominent clerics (one of them Patriarch Yawsep II). This shift of scale is echoed in a later note in the manuscript by a different hand, this time concerning a plague that struck in 1771.49 The author of this note, whom we can almost certainly deduce from an ownership note was the grandson of the original scribe, also named ʿAbd al-Aḥad, again began by recording deaths within his own family, before noting figures for deaths among the Chaldeans of ʿAyn Tannūr and then Diyarbakır more generally. These two passages on the plagues of 1712 and 1771 are crucial to our perception of CCM 12 as a condensed archive. One key characteristic of record-keeping is the notion of continuity: the state of ‘work in progress’ that defines its existence.50 Recounting events almost sixty years apart, the two plague narratives are a striking example of efforts within one family to perpetuate a record. ʿAbd al-Aḥad the Younger updates his grandfather’s account, following the same format and subject matter.

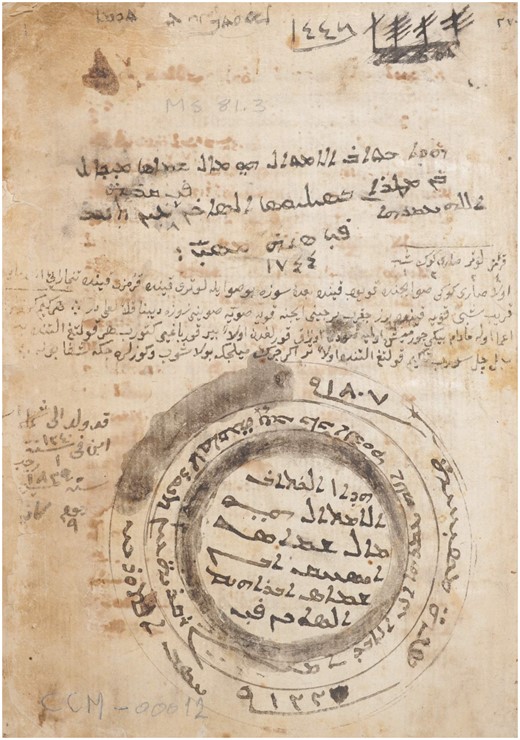

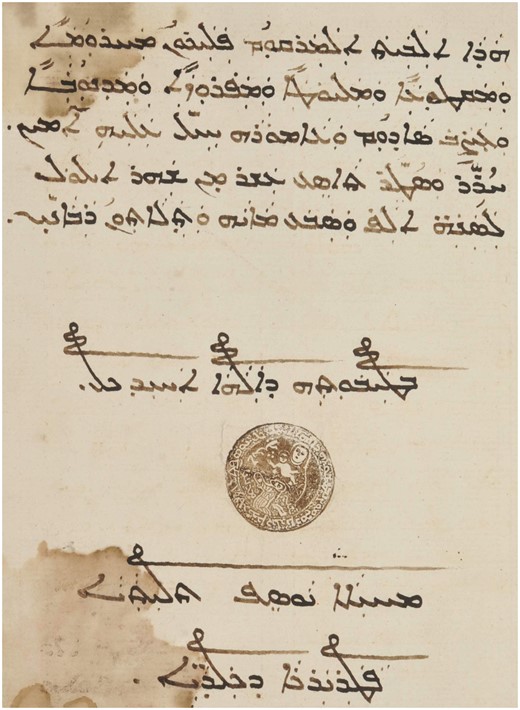

Ownership notes also shed light on the practices of preservation that generated the archive. CCM 12 remained in the possession of the family of ʿAbd al-Aḥad, the original scribe, for three generations. A note records that in 1744 the manuscript was owned by ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s son, Deacon Mikhāʾīl.51 A later undated note records the sale of the manuscript by Mikhāʾīl’s son ʿAbd al-Aḥad, who had presumably inherited it from his father, to a certain Deacon Isḥāq son of Ibrahim.52 Elsewhere in the manuscript Isḥāq again records his ownership, this time providing a date of 1807 (see Plate 1).53 It is difficult to confirm whether Isḥāq was a member of ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s Chaldean community, although it appears probable. Certainly, these notes confirming the manuscript’s ownership by the scribe’s son and grandson testify to the family efforts that kept this miniature archive alive, not only by preserving it in material terms, but by continually updating its contents.

1. Turkey, Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, MS 12 (HMML Pr. No. CCM 00012), fo. 1r, ownership notes of Mikhāʿīl son of ʿAbd al-Aḥad and Isḥāq son of Ibrahim. Photo courtesy of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Saint John’s University, MN, USA and the Chaldean Cathedral, Mardin, Turkey. Published with permission of the owners. All rights reserved.

CCM 12 was not a static scribal creation, but a living project which traversed time and individuals. It reveals that a single manuscript could operate as a condensed archive, commemorating the history of a community and its confessional practices, and ensuring its remembrance to posterity. The manuscript illuminates multiple layers of identity and belonging, moving between ʿAbd al-Aḥad the pious individual, his family, the Chaldean community of his village, and the Diyarbakır region as a whole. While CCM 12 may have lacked the physical repository traditionally associated with an archive, the confessional, communal and familial bonds manifested in its pages bear a force of their own. Moreover, as a record on its front page of the birth of a baby boy to a deacon in 1825 reminds us, its usage as an archive long outlived its founders.54

Although this section has focused on CCM 12 as an archive in itself, it should not be considered in isolation. We have identified a body of manuscripts originating from the same social and geographical setting, produced by connected individuals with shared scribal practices. To take one striking example, another account of the plague of 1771 survives, written by a priest, Yūsuf, from Diyarbakır.55 Although Yūsuf wrote from a different location, and in a different script (Arabic rather than Syriac), his account has a similar structure to that of ʿAbd al-Aḥad in CCM 12; he even names the same five priests as victims of the plague, suggesting a context of shared information and styles of record-keeping across the two manuscripts.56

II LOCATING A DISPERSED ARCHIVE

CCM 12 should thus be seen as part of a wider archive, one scattered in notes and texts across numerous manuscripts never kept in one single location. Recent scholarship on European record-keeping has broadened the definition of archive. Liesbeth Corens’s important work on the ‘counter archives’ of English Catholic expatriate communities has shown the possibility of studying record-keeping beyond ‘recognizable national and institutional archives’, record-keeping that was sometimes geographically dispersed.57 Scholars now recognize that European practices did not represent the only form of record-keeping: Randolph Head has suggested that we speak of different ‘archivalities’, of which European archivalities were only one manifestation.58 The editors of an important recent volume on early modern archives, however, warn of the risks of the overly loose use of the concept, risks including overlooking the ‘materiality’ of the archive.59 They also suggest that scholars should ‘avoid too broad an elision between manuscript culture and record-keeping’, since producing material in manuscript form is an ‘act of publication’ for a current audience, whereas a record is intended less for circulation than for posterity, and has a particular juridical significance.

Our unconventional collection of manuscripts around CCM 12, which we will refer to as the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive, pushes at the boundaries of any conventional definition of archiving. Manuscripts are its core, while it does not possess the typical material characteristics of conventional archives. Nonetheless, it serves a clearly archival function, recording information about events including births, ordinations and deaths within a defined community: the Diyarbakır Chaldeans. In this section, therefore, we argue for a rethinking of definitions of archives, focused less on their physical form and link to a defined repository than on their purpose: preserving information over time about a group, with the intention of reinforcing that group’s sense of communal belonging. Our series of records gains cohesion not from any single repository, but from overlapping circles of scribes, families and churches, which could be termed an archival community.60 It was also connected by scribal practices, including the shared use of new religious formulae. It had institutional elements, but was not linked to one clearly defined institution, beyond the fairly nebulous Chaldean Church. It cannot be termed either public and institutional, or private; it transcends these boundaries, its manuscripts shifting between different types of ownership and usage.

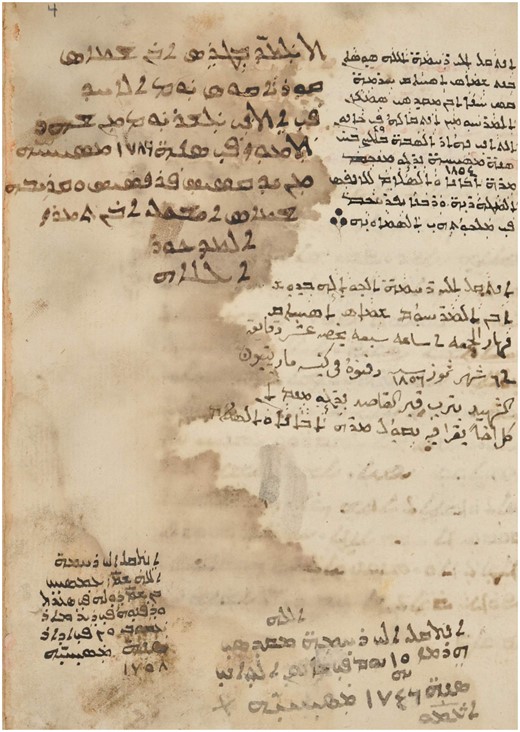

The Diyarbakır Chaldean archive as it survives now comprises about forty-five manuscripts, almost all written in Syriac or Arabic Karshuni.61 Their contents are predominantly religious, including biblical lectionaries,62 orders of service and other ritual texts,63 psalters,64 catechisms and didactic treatises,65 and theological and mystical works.66 These religious texts may seem a world away from that of the archive. But it is on their pages that scribes and other users record more typical ‘archival’ material: an early eighteenth-century psalter, for instance, contains several records of baptisms, ordinations and deaths from 1742 until as late as 1858 (see Plate 2).67 In a theological manuscript of 1720, a priest, Yūsuf, described a plague in Diyarbakır in the 1770s, as well as his own marriage and ordination.68 Not all of the manuscripts that we associate with this archive contain this kind of information. Some contain notes that are more directly linked to the history of the manuscript, recording ownership and sales; others contain no paratextual elements beyond a colophon recording the name of the scribe and the date and the location of the manuscript’s copying. Nonetheless, we believe that these manuscripts also belong within the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive. The information contained in the colophon is in itself a form of record-keeping, and there is no reason to separate records of book production, sales and donations from records of ordinations, births and deaths.69 All appear as important events in local history, and are sometimes linked: books are re-gifted after deaths, or donated on behalf of deceased individuals.70 In addition, as we will see, the manuscripts are closely connected through individuals and churches involved in their production.

2. Turkey, Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, MS 289 (HMML Pr. No. CCM 00289), fo. 4r, records of deaths and other events. Photo courtesy of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Saint John’s University, MN, USA and the Chaldean Cathedral, Mardin, Turkey. Published with permission of the owners. All rights reserved.

The religious contents of the manuscripts also provide cohesion. A religious text may not appear to us as a ‘record’. But, in the context of a recently established church, they could fulfil a record-keeping function. This is perhaps most obvious in the case of the Life of Yawsep, but even the copying of the new Chaldean liturgical texts, which had been revised by Patriarch Yawsep II and other Chaldean clerics to fit with Catholic precepts, arguably served to record and consolidate the changes made in the Chaldean Church. This ‘record-keeping’ aspect of liturgical texts is sometimes emphasized in paratexts. In 1734, Mikhāʾīl, ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s son, copied a revised biblical lectionary containing Catholic festivals produced by his father; after the text he noted that his father had compiled it while he was a priest, piously enduring the heavy burden of assembling various scattered readings.71 In recording the circumstances of the text’s production, he inscribed both its history and his father’s piety for future users of the manuscript. In 1709 ʿAbd al-Aḥad copied a Chaldean liturgy revised by Yawsep II. An introduction records that Yawsep was inspired to rewrite the liturgy upon realizing that the existing prayers for feast days ‘were rife with heresies’.72 It reports that Yawsep had removed these heresies, corrected textual errors, arranged the book in a fine melody suitable for chanting, and added missing feast days. ʿAbd al-Aḥad does not simply copy the new liturgy for practical reasons; rather, he records the circumstances of its creation as part of a broader mission, achieved across his manuscripts, of documenting the formation and doctrines of the new Chaldean Church.

Manuscripts, then, can constitute a communal archive, in which text, paratexts, colophons and marginalia work together. Liesbeth Corens has noted perceptively that ‘archives work at the interface between past and future’.73 The same is true of manuscripts. They transmit traditions, but can also record changes and developments, as in the case of the Chaldean liturgy. They may have a practical function in the short term, but they also look towards their future users. They can also step out of human time to interact with the eternal: Shmūnī, granddaughter of ʿAbd al-Aḥad, donated a manuscript to a church on behalf of the souls of her deceased daughter, father, grandfather and brother.74 Past, present and future coalesce in their pages.

Having established the archival potential of manuscripts, we can turn to other features of the dispersed Diyarbakır Chaldean archive. Most of the manuscripts are now in the collection of the Chaldean Cathedral in Mardin, although before the First World War some of these had been in Diyarbakır.75 Other parts of the archive are dispersed more widely: one manuscript is in Our Lady of Bzoummār Convent in Lebanon;76 two are in the Chaldean patriarchate in Baghdad;77 one in a monastery near Baghdad;78 one in the Mar Behnam Monastery in Mosul;79 at least two are in the Vatican;80 one in Berlin;81 one in Birmingham;82 and one in London.83 One important manuscript, produced by Theresa, daughter of the priest Khajjū, in 1766–7, is apparently lost, and known only from an early catalogue.84 None of this is exceptional for a Middle Eastern manuscript collection: many manuscripts have been moved and dispersed over the centuries due to war and instability, ecclesiastical reorganization, contacts with Western Catholics, and purchase or looting by European orientalists.85

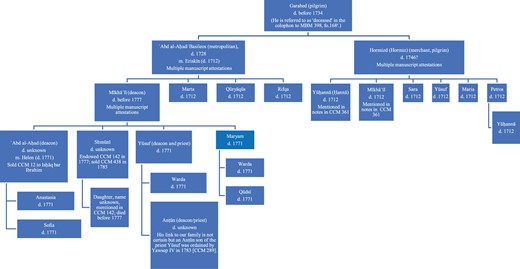

What is striking is that the manuscripts of the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive were never held in one physical centre. Rather, the archive was connected through its links to several overlapping circles of families, scribes and churches, which gave the archive an intangible unity. The family of ʿAbd al-Aḥad is at the heart of the archive. His relatives played a dominant role in three ways: as producers and commissioners of manuscripts and records, as owners of manuscripts across multiple generations, and as subjects of the information recorded. We find references to five generations of his family in the manuscripts, with sufficient detail to reconstruct a family tree (see Figure). ʿAbd al-Aḥad himself copied more than ten of the manuscripts in the archive;86 he restored another;87 donated one to the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs in ʿAyn Tannūr;88 purchased another from a church in Mardin;89 and recorded his own ordination as bishop in another.90 His son Mikhāʾīl was equally prolific, producing more than fifteen surviving manuscripts;91 he also gave a manuscript to his son Yūsuf,92 and he recorded his ownership of several other manuscripts.93 ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s brother, Hormizd, commissioned at least three ornate manuscripts from his brother.94 He is also the subject of notes in several manuscripts: one records him bailing out the church of Saint Qūryāqūs; two document the death of his children; one records his own death in 1746.95 Other members of the family also appear in the archive. We have seen that the plague accounts in CCM 12 focus on ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s relatives. Notes also recorded the ordinations of two of Mikhāʾīl’s sons, Yūsuf and ʿAbd al-Aḥad,96 and sales and donations of manuscripts made by Mikhāʾīl’s children ʿAbd al-Aḥad and Shmūnī.97 Several manuscripts were passed down within the family, across three generations, from ʿAbd al-Aḥad to Mikhāʾīl, and to his children ʿAbd al-Aḥad and Shmūnī.98 ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s family thus appear as producers, owners and subjects of the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive; at one level it could be seen as their family archive.

Family Tree of the Descendants of Garabed

Yet the archive cannot only be explained in terms of this one family. Several other scribes were active in the same period in ʿAyn Tannūr, also copying Chaldean manuscripts, using very similar language in colophons, and sometimes showing interest in ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s family. One striking example is the young scribe Theresa, daughter of Khajjū from ʿAyn Tannūr.99 A manuscript she copied in 1766–7, aged 15, contains a list of deaths within the Chaldean community from 1692 until 1757.100 Sadly the manuscript appears to be lost, but Scher’s catalogue entry reports that the deaths listed included that of Metropolitan Basileos of ʿAyn Tannūr on 3 January 1728 — that is, ʿAbd al-Aḥad son of Garabed himself. Theresa’s great-great-grandfather is the first death listed in the manuscript; the deaths also include her ancestors, the deacon ʿAbd al-Karīm and priest Bākūs. The list thus takes on the character of Theresa’s family history, interwoven with that of prominent Chaldeans such as Metropolitan ʿAbd al-Aḥad. Social ties within ʿAyn Tannūr probably connected these scribes, but the archive was not simply ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s family archive.

As well as families, churches were also very significant in giving the archive unity. Most of the manuscripts in the archive can be linked to four churches. Most important was the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs in ʿAyn Tannūr, which was not simply a repository for the preservation of the collection, but an active site of its creation. We know from a Western observer that ʿAyn Tannūr only contained two churches in this period, one Chaldean (that is, Saint Qūryāqūs), and one Armenian.101 Saint Qūryāqūs was thus the only ecclesiastical place of worship for Chaldeans in this village. It also formed the centre of Chaldean scribal culture. Numerous manuscripts were copied there by scribes including ʿAbd al-Aḥad and his son Mikhāʾīl, as well as other Chaldeans such as ʿAbd al-Masīḥ son of Yūḥannā, the priest Daniel son of Adam, the deacon Tūmā son of Qūryāqūs, and Khajjū son of Tūmā.102 ʿAbd al-Aḥad also repaired a manuscript there.103 It must therefore be seen not only as a passive repository of records, but an important site where scribes, many of them members of the clergy, communicated with and influenced each other. It was also a centre of Chaldean devotion. ʿAbd al-Aḥad copied and donated several manuscripts to Saint Qūryāqūs.104 His brother Hormizd commissioned one manuscript for Saint Qūryāqūs and endowed another to it after the death of his children, its original recipients.105

Other churches appear more commonly as recipients of manuscripts rather than sites of production. The Church of Saint Pethion in Diyarbakır was arguably the spiritual centre of the Yawsep Chaldean movement.106 ʿAbd al-Aḥad copied one manuscript there in 1693,107 but it more frequently appears in the archive as a dedicatee, benefiting from the gift of several manuscripts, including at least one copied in Saint Qūryāqūs.108 Less important were the Church of Saint Hormizd in Mardin, which at various points owned three manuscripts produced by ʿAbd al-Aḥad and Mikhāʾīl, and the Church of Saint Shmūnī in the village of Jarūkhīyā, to which Hormizd donated a manuscript.109 Thus, although the archive had no single geographical location, there were certain sites crucial to its production and preservation, which gave the archive another sort of unity.

The archive also gained cohesion from developments in scribal practices. Our scribes predominantly wrote in Syriac and in Karshuni (Arabic language in Syriac script). This use of Syriac script may in itself have been a conscious strategy of differentiation from other Ottoman communities who used Arabic script.110 Syriac had a long manuscript tradition with well-established, albeit flexible, formulae for writing colophons, which are more common and lengthier in Syriac manuscripts than in many other traditions.111 Colophons mattered: they helped to legitimize the manuscript and also to endow the scribe and other figures named with authority through their association with the religiously prestigious texts copied.112 They also served ‘to create a community of readers linked across space and time’, by situating the individual manuscript and scribe in relationship to churches, commissioners, ecclesiastical authorities and cities.113 It is thus highly significant that the Diyarbakır Chaldeans developed new formulae for their colophons, based on traditional Syriac colophons but deviating from them in several important respects, in keeping with the Chaldean emphasis on papal primacy and orthodox Catholic doctrine. First, whereas traditional Syriac colophons often named the reigning patriarch of the day, the Chaldeans now frequently referred to the incumbent pope before mentioning their patriarch.114 The pope is endowed with epithets including ‘our Lord and Lord of all Christianity’,115 while the patriarch is typically identified as ‘patriarch of the Chaldeans and all the orthodox in the East’.116 The pope is thus inscribed as the leader of all Christians, while the patriarch’s role is defined in terms of the Eastern Chaldean community.

Second, the Chaldean scribes often refer to the protection of Mary ‘Mother of God’, in a clear reference to one of the main doctrinal differences between Catholic Chaldeans and the Church of the East from which they had seceded.117 Chaldean scribes thus reflected and reinforced their new Catholic Chaldean identity in colophons. Given the importance of colophons as records, these changes represent a significant reframing of forms of archiving: information was now preserved in a deliberately Catholic framework, and individual events situated in a broader Chaldean world view. The Chaldean focus of this record-keeping project is also shown in the CCM 12 plague accounts, which focus on deaths within ‘our Chaldean community’.118 Some figures involved in manuscript production explicitly inscribed their Chaldean identities, including an illustrator, ‘Zachariah the Chaldean’, and a scribe, ‘Daniel of Alqōsh, the Catholic, the Chaldean’.119 This widespread recording of Chaldean beliefs and self-identification further suggests that these individual manuscripts should be seen as part of a wider transformation in record-keeping by the Chaldean archival community.

Despite the lack of an institutional repository, the archive did nonetheless contain what we might regard as institutional ecclesiastical elements. As discussed, many of the manuscripts were copied in or donated to churches. Notes recorded details of church events such as baptisms and ordinations, thereby inscribing the membership and structure of the Chaldean Church. Many of the scribes had ecclesiastical positions.120 The patriarchs were also involved, not only as passive subjects of records, but also as authors of notes and participants in manuscript transfers. Yawsep III, for example, wrote a variety of notes on subjects as diverse as his receipt of the pallium from the pope, his ordination of a bishop and a priest, a property purchase by Hormizd son of Garabed, the death of Hormizd’s sons, and the ownership history of a liturgical manuscript.121 It may seem surprising that the patriarchs recorded these events in their own hands, but their personal prestige must have rendered additional authority to the records, in the absence of a more official system of record-keeping. It is also true that the Chaldean Church was at this date a very small institution, consisting in large part of the patriarch, one or two bishops and a handful of priests.122 Although it had symbolic prestige and authority, it had few resources, relying on donations and loans incurred from its members. In this context, the institutional was intensely personal: the patriarch himself in a sense embodied the Chaldean Church. This helps to explain why the Chaldean community produced an unconventional archive of this form, lacking one physical centre.

Although dispersed, the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive was remarkably cohesive. It gained unity not from any single repository, but from a series of overlapping circles involved in its creation and transmission, including families, scribes, churches and patriarchs. Given that most manuscripts were the product of more than one individual, from scribes to commissioners to owners to note-makers, it makes sense to speak not of any individual creator but of an archival community. The shape of the community determined the shape of the archive: in the case of the Diyarbakır Chaldeans, a small, institutionally flexible community held together by personal social ties produced an unconventional archive, reliant on intangible connections between its creators.

III ARCHIVES AND COMMUNITY FORMATION

The archive thus reflected and was shaped by the emergent Chaldean community. But this was not a one-way process: the archive also created and imagined the community. We cannot disentangle the archive from the community, not only because the archive provides almost all of our knowledge about this community, but also because, in a very real sense, the archive created and fostered community belonging.123 This happened at both a practical and an imagined level. In terms of the former, practices associated with archiving, including the gifting of manuscripts, the education of children, and the recording of acts of piety and generosity, served to reinforce community bonds. Lay people participated as well as clergy, demonstrating the porous boundaries between lay and clerical piety. The archive was mobile, moving between the ownership of different figures and institutions, further cementing community cohesion. But at the same time as the archive established real links, it also imagined the community on a more illusory level. Sources in Western repositories reveal that the Chaldean community was small and embattled, severely threatened by their rivals in the Church of the East. Barely a hint of these tensions appears in the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive, which instead presents an idealized vision of a community united under the patriarch’s pious leadership.

We draw here on Benedict Anderson’s famous concept of the imagined community.124 Applying Anderson’s concept to the fifteenth-century Church of the East (although not in terms of archiving), Thomas Carlson has argued that the term ‘community concepts’ is preferable to ‘imagined communities’, in part because it ‘avoids connotations of unreality and invention’.125 In the Chaldean case, however, we think that these connotations are helpful, because there were illusory and fictive elements in how the archive imagined its community, elements which could have real consequences. We want to advance the investigation of the relationship of archives and communities, by seeing archiving not only as part of a broader process by which a community imagined itself, but also by exploring how archives themselves imagined and created communities. Indeed, we could speak here of the agency of the archive, as it had concrete historical effects. To a large degree, this represented the agency of the individuals involved in its creation and dissemination, recalling Gell’s theory of artistic products with ‘secondary’ agency enacting the ‘extended mind’ or ‘distributed personhood’ of their creator.126 Historians of early modern book culture have shown that Gell’s model can prove useful for understanding the social roles of books and manuscripts as well as of visual art.127 It becomes more complex when applied to an archive produced not by an individual but by a community. Importantly, Gell did suggest that objects could embody the agency not only of individuals but of collectives.128 The archive in its entirety bore the potential for effects beyond the capability, and possibly even the intention, of any one of its various creators. By exploring this creative, productive, aspect of the archive, we hope to offer a new perspective on community formation within the recently established Chaldean Church in Ottoman Mesopotamia.

First, let us consider how the archive created real ties within the community. Its manuscripts served as conduits for a host of social bonds, primarily as gifts; manuscripts were gifted between individuals, including from fathers to sons,129 but more often from individuals to churches.130 Sometimes donations were made on behalf of departed souls, further complicating the nexus of relationships involved; in a sense Shmūnī, when she gave a manuscript to a church on behalf of her deceased relatives, was making a gift as much to them as to the church itself, since it was intended to benefit their eternal souls.131 Paratextual notes recorded these acts of generosity, preserving them for future generations. Events thus operated on two levels: first, a manuscript was gifted, creating an immediate social effect. At the same time, this gift was recorded in the pages of the manuscript, creating a potential effect on any future reader or user of the text. Unfortunately, we rarely have direct evidence of how people responded to these manuscripts. Nonetheless, by exploring the materiality of the manuscripts, we hope to elucidate how text and paratext operated together to encourage cohesion within the Chaldean community.

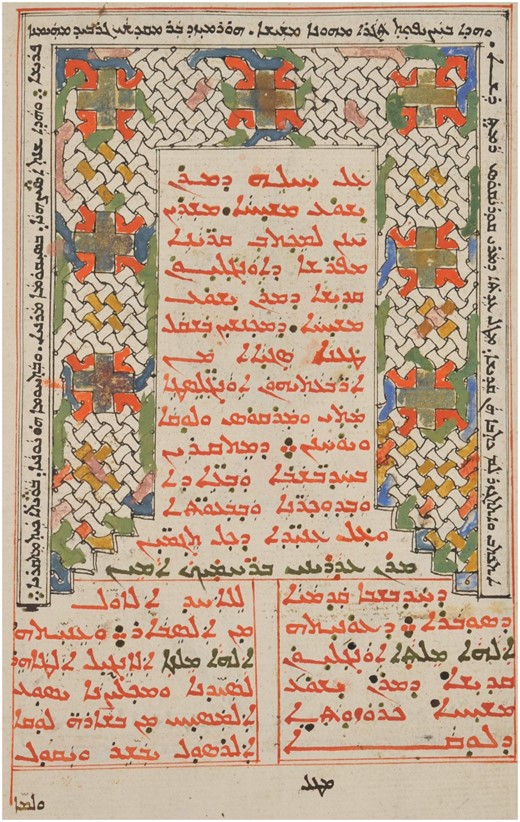

An ornate gospel lectionary copied in 1695 provides a compelling example.132 It was commissioned by Hormizd son of Garabed from his brother ʿAbd al-Aḥad, the scribe of the manuscript, for the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs. ʿAbd al-Aḥad recorded Hormizd’s commissioning in multiple places, including, as was conventional, in its lengthy colophon:133

This book … was written at the command … of the true believer, perfectly orthodox, guardian of monasteries and religious houses, and father of orphans and widows …

Hormizd son of Garabed, pilgrim, the brother of the wretched scribe, for the very holy Church … of Saint Qūryāqūs … and he caused it to be written from his own means, and he bestowed it … with his whole heart willingly … may Christ absolve … his sins … and grant him fellowship with all of his saints.134

Rather than simply recording the details of the commissioning, ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s ornate language provides a guide as to how the reader should interpret it. Hormizd’s charitable donation appears as part of his wider role as Christian leader, protecting the vulnerable. Epithets referring to the patronage of monasteries, orphans and widows were often applied to patriarchs;135 here, however, they are bestowed upon Hormizd, a layman. His donation to the church, made willingly from his own resources, also serves, the scribe implies, to earn him heavenly credit with Christ. Strikingly, at some point Hormizd’s name has been erased from the colophon, although the contextual information identifying him survives; this could have been an act of humility by Hormizd himself, but is perhaps more likely to have been carried out by a later owner of the manuscript. In any case, it shows that names and their records mattered; it was important to someone to remove Hormizd’s name.

The colophon would, perhaps, only be read by some users, interested in actively seeking out details of the manuscript’s creation. But Hormizd’s donation is also recorded in a much more prominent place, visible to more readers: on the title page of the gospel lectionary itself, in a note surrounding an ornamental border.136 The note, which concisely records Hormizd’s commissioning of the manuscript, is visually striking, written in black on a page dominated by red and a multi-coloured border (see Plate 3). It thus served to associate the manuscript very strongly with Hormizd’s generosity towards Saint Qūryāqūs.

3. Turkey, Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, MS 64 (HMML Pr. No. CCM 00064), fo. 7v, title page of gospel lectionary with ornamental border surrounded by note in black detailing commissioning by Hormizd son of Garabed. Photo courtesy of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Saint John’s University, MN, USA and the Chaldean Cathedral, Mardin, Turkey. Published with permission of the owners. All rights reserved.

We know, in fact, that this association was real and lasting. A note written at the end of the same manuscript by Yawsep III in 1730 records that Hormizd had helped Saint Qūryāqūs out of financial difficulty by buying one of their properties and endowing it back to them.137 It cannot be coincidence that Yawsep wrote this note recording a second act of generosity by Hormizd to Saint Qūryāqūs here; thirty-five years after Hormizd’s original commissioning of the manuscript, the manuscript was still associated with this generous lay donor, revealing the power of the record to cement and maintain community bonds.

The note itself is extremely interesting, in both content and form:

May it be known to every believing brother that the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs owned a property. However, when great strain was put on our father … Yawsep III, due to affairs in Mosul concerning the Catholic faith, the brothers found themselves in dire need, and this abundance of hardship convinced them to sell the aforementioned property. However, pilgrim Hormizd, son of the deceased pilgrim Garabed, overwhelmed by his zeal for the faith, took pains to purchase [the property] out of his own pocket for 160 piastres and endowed it to the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs …

This property is flanked from the north by the house of Jum’ah the barber; and from the direction of the qiblah by the house of Ibn Farrah; and from the west by the house of Ibrāhīm; and in the fourth direction by the main road. I, the wretched … Yawsep III, writer of these words, say to anyone who dares to sell the aforementioned property: may he be excommunicated, cut off … discreditable.

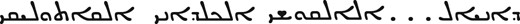

Two themes appear particularly important in this record. First, this donation is again framed in terms of Hormizd’s piety: Yawsep presents it as the act of a devoted Catholic believer, ‘overwhelmed by his zeal for the faith’. Second, the note has a formal, legalistic aspect. Not only does Yawsep go on to record the location of the property carefully, specifying its neighbours on all sides, but the layout of the note is noticeably formal. The Karshuni note is followed by Yawsep’s subscription in Syriac, embellished with flourishes on the long letters: ‘by the grace of God … the weak Yawsep III, patriarch of the Chaldeans’.138 Yawsep has also affixed his seal, which bears an image of the Virgin and Child (see Plate 4). CCM 64 thus serves as witness to a decades-long relationship between Hormizd and the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs. Indeed, it seems likely that the manuscript not only testified to this relationship, but encouraged it; the records of Hormizd’s initial donation served as an ongoing reminder to all parties of his pious devotion to the church, and even, perhaps, created an obligation to continue supporting it.

4. Turkey, Mardin, Chaldean Cathedral, MS 64 (HMML Pr. No. CCM 00064), fo. 206r, end of Karshuni note with Yawsep III’s Syriac subscription and seal. Photo courtesy of the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, Saint John’s University, MN, USA and the Chaldean Cathedral, Mardin, Turkey. Published with permission of the owners. All rights reserved.

The example of CCM 64 suggests that records of donations mattered; they still had resonance decades after they were first written, and contributed to ongoing social ties. The inscribing of religious affiliations through the new colophon formulae may have had similar effects, reinforcing identities within the Chaldean community across the years. Importantly, this was not simply a clerical community. While many of the scribes of the manuscripts had some ecclesiastical status, lay people also participated in manuscript production and dissemination. As in many European contexts, lay and clerical piety cannot be clearly distinguished:139 the merchant Hormizd was venerated with the same epithets often applied to bishops and patriarchs. Women could also participate, from Theresa, the young scribe, to Shmūnī, who endowed and sold manuscripts, to Warda, who together with her husband donated a manuscript on behalf of their deceased son Ibrahim.140 Practices associated with manuscripts and archiving contributed to community cohesion, offering a form of piety in which a wide range of believers could participate (albeit primarily those of some financial means).

It is important to note here that the manuscripts were mobile and fluid in both usage and ownership. This helps us to understand how this archive operated and contributed to community cohesion; manuscripts circulated within the community, making records accessible, visible and beneficial to more people. Manuscripts moved between what we might regard as private and public or institutional ownership, from the hands of individuals to churches and vice versa. Hormizd, for instance, commissioned a theological manuscript from his brother ʿAbd al-Aḥad in 1707. Patriarch Yawsep II recorded that Hormizd had

requested the copying of this book for his blessed children Ḥannā and Mikhāʾīl. And this aforementioned one [Hormizd] instructed that it should be read by those desirous of knowledge, saying: ‘I, the wretched one, ordered and shall order my children that no one who wishes for the salvation of his soul and to become versed in theology should be prevented from [reading it]’.141

This implies that Hormizd’s sons should make the manuscript available to anyone who wished to learn from its contents; its owners had a duty to share it with a wider public, suggesting a concern with community. Furthermore, after his sons died in the 1712 plague, Hormizd endowed the manuscript to the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs;142 it moved from family to church ownership, and was seemingly suited for both uses. A note added to a liturgical manuscript from 1707 records that it had been owned by Patriarch Yawsep II, but was then sold by the Church of Hormizd in Mardin to Bishop ʿAbd al-Aḥad son of Garabed; it was subsequently endowed by Yawsep III back to the Church of Hormizd.143 There are some gaps in this manuscript history, but it is clear that it moved between ‘individual’ ownership, albeit by high-profile clerics, and church ownership. It is not implausible that priests who owned manuscripts would have brought them to churches to use in the liturgy. In 1755 Mikhāʾīl son of ʿAbd al-Aḥad gave a liturgical manuscript to his son Yūsuf, a ‘servant of the Church of Saint Qūryāqūs’.144 We know from another manuscript that Yūsuf had been ordained as a priest in the previous year;145 it seems possible, therefore, that Mikhāʾīl gave him this manuscript both as a mark of pride at his ordination, and as a practical gift, to use in church services.

In view of this, it makes little sense to differentiate strictly between individual/private and institutional/public ownership. Research on European archives has shown that this distinction is often artificial and unhelpful;146 it is particularly inapplicable to the relatively fluid institutional context of a newly established, small church. Manuscripts were mobile and their ownership was changeable, which helps us to understand how a seemingly dispersed collection of manuscripts could function as an archive. As manuscripts moved, and were used and reused, their records, from marginal notes to the liturgical texts proclaiming the new Chaldean faith, were seen and used by various members of the community in different contexts. Donors such as Hormizd imagined manuscripts as community resources, offering knowledge and help to any pious believer, and reinforcing the Chaldean faith.

But the archive also contributed to imagining the community in a rather different way, presenting an idealized picture of a church which was in reality facing existential threats, above all from the rival Church of the East patriarchs. Only the occasional hint of conflict appears in the archive. The Life of Yawsep I describes Eliya IX’s opposition to Yawsep, but suggests that Yawsep successfully overcame this through God’s support; ʿAbd al-Aḥad does not refer to ongoing conflicts with Eliya’s followers. The clearest sign of tension appears in the note recording Hormizd’s bailing out of Saint Qūryāqūs, which refers obliquely to Yawsep III’s troubles in Mosul. Although the note provides no detail, this episode is attested in European sources. It seems that in 1723 Yawsep III had decided to extend his influence into Mosul, traditionally beyond the purview of his patriarchal predecessors. In pursuit of this goal, he had tried to appoint the Catholic priest Khidr son of Hormizd as Chaldean bishop in Mosul, using ʿAbd al-Aḥad son of Garabed as his envoy.147 This prompted fury from Eliya XI, who redoubled his efforts to destroy Yawsep’s church, in part by encouraging the Muslim governors of Diyarbakır to extort heavy payments from Yawsep.

After these events, Yawsep III desired to leave Mesopotamia and move to Rome. The Maronite Giuseppe Simone Assemani attributed this to the ‘continuous vexations of the heretic Nestorians and the infidel Mohammedans, who … do not cease from condemning him to considerable sums of money’.148 The Propaganda Fide initially refused Yawsep’s request for permission to leave for Rome, but later, after the patriarch himself spent a few months in Mosul in 1728, he prompted more hostility from the rival church, was imprisoned and only released after paying further heavy fines. In 1731 he left Diyarbakır for Constantinople and then Europe, where he ended up spending almost ten years, returning only in 1741.149 He left his people considerably poorer: a list of his debts survives in Rome, revealing that his creditors included the church of ʿAyn Tannūr (presumably Saint Qūryāqūs), which had loaned 1,800 piastres to Yawsep, as well as various lay people, notably Saja of Diyarbakır, who together with her daughter Maria had lent Yawsep the vast sum of 8,000 piastres.150 In 1767 the Discalced Carmelite Emmanuel Balliet issued a harsh verdict on Yawsep, stating that in 1728 the Chaldean Nation had been ‘entirely ruined by the imprudence of the last Chaldean Patriarch’.151

Rhetorical exaggeration aside, it is clear that the community was facing considerable difficulty. Yawsep III’s career was not an unmitigated failure; despite his troubles in Mosul, he was more successful in winning over a Church of the East bishop in Seert to the Chaldeans, and in appointing a new bishop in Mardin.152 Nonetheless, the Chaldeans were an embattled minority who lacked consistent protection from local leaders. They felt Yawsep’s absence during his Roman sojourn keenly, writing many desperate letters to Rome imploring him to return. One characteristic example, apparently written by the ‘priests, clerics and other lay people’ of Diyarbakır, urges the cardinals and pope to send Yawsep back to them, describing themselves as ‘orphans without a Father’, threatened by ‘Heretics [who] surround us on every side like ravening wolves’.153 They may have exaggerated the level of threat faced, but clearly strongly desired Yawsep’s return from Rome.

And yet almost no sign of this conflict appears in the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive. Indeed, during the 1730s, while Yawsep was absent in Rome, scribes continued to name Yawsep as patriarch in their manuscripts with no reference to his departure.154 A lectionary copied by Mikhāʾīl son of ʿAbd al-Aḥad in 1734 is typical: the colophon reports that the book was completed in ‘the days of the excellent fathers’, Clement XII and Yawsep III, ‘patriarch of the Chaldeans and of all the orthodox in the East’, ‘may God … elevate their thrones … and make them triumph against their opponents’.155 The mention of opponents could perhaps be an oblique reference to Yawsep’s ecclesiastical rivals, although a wish for God to grant the patriarchs prosperity is typical of Syriac colophons. Nonetheless, the colophon certainly suggests that Yawsep was the current head of the Eastern Catholics; no reference is made to his absence or to the difficult situation of his followers. It thus records an idealized vision of the church hierarchy, glossing over its difficult realities.

This cannot be explained simply as a matter of form or genre: we have seen that it was possible to make innovations in colophons, and that notes recorded a range of different events and situations. Earlier Syriac colophons and notes had recorded visits by East Syrian patriarchs and bishops to Rome.156 Instead, this silence should be seen as a deliberate choice not to document the contemporary struggles faced by the church. The archive was primarily a record of successes and acts of piety: of ordinations, of births, of donations, of pilgrimages, of the reform of the liturgy, of the creation or transfer of manuscripts, and of important events such as the receipt of the pallium from the papacy. It did also record deaths, but this served to recall the membership of the Chaldean community and to create links between its past and present members. It was not a record of failures, debts or struggles. It created an idealized vision of a successful church bound together by acts of piety, by shared adherence to Catholic doctrines, and by wide-ranging social ties. It is difficult, unfortunately, to assess the effects of this imagining of the community. Contemporaries must have been aware of its limitations. But to future generations it presented a picture of success, erasing from history the tensions within the church over their absent leadership. Even for contemporaries, it is possible that the process of recording an idealized vision of the church helped to reinforce solidarity in a time of difficulty. In spite of his absence, Yawsep III was present through the notes that he had written in earlier manuscripts, and through scribal affirmation of his leadership in colophons. Certainly, the Chaldean community survived these trials; the archive continues for several generations after this particularly difficult period. The archive may thus have contributed to bringing into reality aspects of its imagined ideal community.

conclusion

The Diyarbakır Chaldean archive challenges many conventional definitions of archives. It bursts dichotomies sometimes applied to record-keeping projects, such as public or private, family or institutional. It had no fixed geographical centre or holding institution, and the information it contained was diverse in form and function, from records of property transactions to revisions of liturgical texts. But recognizing this project as archival is helpful in several ways, both for understanding the Diyarbakır Chaldean manuscripts more fully, and for enhancing approaches to early modern Catholic archives. First, it helps us to uncover the more typically archival aspects of the Chaldean manuscripts. It encourages us to explore the relationship between manuscripts, institutions and power; power dynamics were clearly involved in the archiving project, which saw participation from patriarchs, bishops, priests and wealthy laypeople. It helps us to uncover elements of unity in the manuscript records, which might otherwise appear haphazard and disorganized. Most strikingly, the new colophon formulae were applied fairly systematically to the manuscripts, representing a new way of framing the preservation of information. It also helps us to reveal links between text and paratext: to see why, for instance, details of ordinations or donations to churches were recorded on the margins of liturgical texts. It was not simply that liturgical manuscripts had longevity and were therefore a useful place to record information. The liturgy in itself was a record of the new Chaldean religion; the notes contributed to this by commemorating events and people important to the Chaldean community. By thinking of these manuscripts as an archive, we come to appreciate far better their cohesiveness and underlying logic, rather than viewing them as chaotic products of an outdated scribal tradition.

Acknowledging the Diyarbakır Chaldean manuscripts as an archive also enhances our understanding of early modern archives more generally. First, adopting a more fluid definition of archive helps to break down the historiographical barrier between scholarship on European and extra-European Catholicism. It is unsurprising that in contexts where Catholic churches were more recently established, restricted in wealth and membership, and vulnerable to external threats, they would produce less conventional forms of archiving. In the Chaldean case, its decentralized archive reflected the small size of the church and its lack of an established institutional centre. Nonetheless, this was a distinctively Catholic archiving project: the scribes and commentators recorded Catholicizing texts; they inscribed their Chaldean identities in manuscripts; they emphasized papal supremacy and used Catholic formulae to describe Mary. Widening the definition of archive thus facilitates the discussion of Catholic communities and record-keeping across geographical boundaries. In this piece, we have focused on recovering the Diyarbakır archive itself, since this groundwork was necessary before any detailed comparisons can be achieved. But the potential for comparison and synthesis is considerable. What parallels might be found with archiving practices of other marginal groups of Catholics, such as the English Catholics overseas who produced ‘counter-archives’ to combat Protestant histories?157 What can be learnt from comparing the archives of Chaldean converts in the Middle East with those of the colonized peoples of New Spain?158 Far more differences than similarities might well emerge from such comparisons. But this work is still important to decentre the European Catholic experience and to understand better the local factors that affected archival practices and community formation. Comparisons could also be made to local archiving practices in Mesopotamia among Muslims and other Christian confessions alike.159

Second, the insights gained from the Diyarbakır Chaldean archive encourage us to think dynamically about the factors involved in archival production. The relationships between archives and institutions were not straightforward; an institution such as a church could serve as a site of production and of innovation in record-keeping, even if it was not the dominant repository of the archive. People were involved in different ways — as scribes, note-makers, commissioners, illustrators, donors — and interaction between them encouraged developments. It is helpful to think of an archival community who created the archive and gave it forms of cohesion, while also, through the different interests and customs of individuals involved, engendering elements of variation and diversity. An archive thus becomes a story as much of people and community as of institutions and repositories.

This in turn encourages us to recognize that the archive itself contributed to shaping and supporting the community. Catholic identities, particularly in contexts where Catholics constituted a recently established minority, were often fragile; elsewhere in the Middle East Christians are known to have adopted, renounced, and sometimes readopted Catholicism.160 In the Chaldean context, the archive helped to reinforce Catholic belonging, not only in an abstract fashion by enabling individuals to inscribe their religious beliefs, but also through fostering real social obligations. It recorded and thereby made eternal acts of piety and generosity, creating ongoing social ties which demonstrably survived across decades. It also created an imagined vision of an idealized Chaldean community, emphasizing their successes and minimizing their struggles, and seems to have given the church real strength in a time of difficulty. This dynamic, creative side of archiving provides a new perspective on extra-European Catholic community formation, enabling us to move beyond missionaries as the primary focus of attention.

This fluid approach to archives does bring challenges. In particular, it is much harder to establish the boundaries in both time and space of an archive that lacks a single repository or other clear identifying marker. Archiving practices certainly changed over time. The earliest years of the Diyarbakır Chaldeans, under Yawsep I, saw some experiments in colophon formulae, but the regular form which we have discussed here was not consistently established until the early eighteenth century.161 We find changes again towards the end of this century. Perhaps most strikingly, the descendants of ʿAbd al-Aḥad, the family at the heart of the archive, disappear in the historical record from the late eighteenth century onwards. Was the male line eradicated through plague or other misfortune? Did the family fall from grace within the Chaldean community? Did they record their identities and names in different ways, and are therefore lost from our sight? The nineteenth century saw considerable changes to the Chaldean position, as well as to the broader historical context of the region. The rival Eliya line of patriarchs converted to Catholicism, and subsumed the Yawsep patriarchate back into a larger, blended Chaldean Church.162 The late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries consequently represent a unique moment in the history of the Catholic Church in Mesopotamia. We are lucky that this exceptional archive provides a window into the formation and survival of the community in such turbulent times.

Footnotes

This article was prepared and written as part of the project ‘Stories of Survival: Recovering the Connected Histories of Eastern Christianity in the Early Modern World’, which is supported by funding from a European Research Council Starting Grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 638578). Lucy Parker completed this article while funded as a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, and would like to thank the British Academy for supporting her research. Rosie Maxton is grateful to the Leverhulme Trust and the Somerville College Vanessa Brand Scholarship for funding her doctoral research. We would both like to thank John-Paul Ghobrial, Celeste Gianni, Feras Krimsti, Salam Rassi and Vevian Zaki for their very helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. Remaining errors are of course our own. This article is dedicated to Mandy Maxton.

The manuscript is available online via the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library (hereafter HMML) digital collection, project number CCM 12, at <https://www.vhmml.org/readingRoom/view/132214>.

This Life has never been critically edited, but is available in an Arabic abbreviation and a French translation, neither of them based directly on eighteenth-century manuscripts: for the Arabic, see L. Cheikho, ‘ترجمة يوسف الأول بطريرك الكلدان’ [‘Biography of Yawsep I, Patriarch of the Chaldeans’], al-Mashriq Journal, xix (1921), 124–38; French translation, J.-B. Chabot, ‘Les Origines du patriarcat chaldéen: vie de Mar Youssef Ier, premier patriarche des Chaldéens’, Revue de l’Orient Chrétien, i (1896). We discovered three manuscripts of the text in the collection of the Chaldean Cathedral in Mardin, all available online via HMML, with the project numbers CCM 12 (the autograph), CCM 6, and CCM 281.

ܫܗܝܕ ܚܝ CCM 12, fo. 273v.

Towards the end of the Life he refers to letters he received from Yawsep (ibid., fo. 288v).

Ibid., fos. 1v–9r. Alice Croq and Bernard Heyberger are currently preparing to publish this text.

Ibid., fos. 9v–10r.

Studies include: on the seventeenth century, Martin van Bruinessen and Hendrik Boeschoten, Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir: The Relevant Section of The Seyahatname (Leiden, 1988), esp. 13–63; on the eighteenth century, Yavuz Aykan, Rendre la justice à Amid: procédures, acteurs et doctrines dans le context ottoman du XVIIIème siècle (Leiden, 2016); Ariel Salzmann, Tocqueville in the Ottoman Empire: Rival Paths to the Modern State (Leiden, 2003), esp. ch. 3. The neglect of studies of the eastern frontiers of the Ottoman Empire has recently been noted by Ayşe Baltacıoğlu-Brammer, ‘Neither Victim nor Accomplice: The Kızılbaş as Borderland Actors in the Early Modern Ottoman State’, in Tijana Krstić and Derin Terzioğlu (eds.), Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c.1450–c.1750 (Leiden, 2020), 428.

Aykan, Rendre la justice à Amid, 16–19, 26–7; Salzmann, Tocqueville in the Ottoman Empire, 131.

Hakan Özoğlu, Kurdish Notables and the Ottoman State: Evolving Identities, Competing Loyalties, and Shifting Boundaries (New York, 2004), ch. 3; Aykan, Rendre la justice à Amid, passim; Van Bruinessen and Boeschoten, Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir, 13–28.

Aykan, Rendre la justice à Amid, 30–35; Salzmann, Tocqueville in the Ottoman Empire, 151; Van Bruinessen and Boeschoten, Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir, 29–35; David Wilmshurst, The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913 (Leuven, 2000), 54. On the diversity of the south-eastern empire in this period more broadly, see also Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Scribes and Scriptures: The Church of the East in the Eastern Ottoman Provinces, 1500–1850 (Leuven, 2015), esp. 31–9.

See Van Bruinessen and Boeschoten, Evliya Çelebi in Diyarbekir, 32–3.

On language use in the Church of the East, see Murre-van den Berg, Scribes and Scriptures, 31, 33–5 and passim.

For a summary of Catholicism and the Church of the East in Diyarbakır and its neighbouring villages, see Wilmshurst, Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 49–62.

On these events, see especially J.-M. Vosté, ‘Mar Ioḥannan Soulaqa: premier patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l’union avec Rome (†1555)’, Angelicum, viii (1931); Joseph Habbi, ‘Signification de l’union chaldéenne de Mar Sulaqa avec Rome en 1553’, L’Orient Syrien, xi (1966); Murre-van den Berg, Scribes and Scriptures, 44–54; Lucy Parker, ‘The Ambiguities of Belief and Belonging: Catholicism and the Church of the East in the Sixteenth Century’, English Historical Review, cxxxiii (2018). Many sources related to these events are published in Samuel Giamil, Genuinae relationes inter Sedem apostolicam et Assyriorum orientalium seu Chaldaeorum ecclesiam (Rome, 1902), and Giuseppe Beltrami, La chiesa caldea nel secolo dell’unione (Rome, 1933).

For a narrative, see Murre-van den Berg, Scribes and Scriptures, 51–60.

On Yawsep’s career, see Albert Lampart, Ein Märtyrer der Union mit Rom (Einsiedeln, 1966); Murre-van den Berg, Scribes and Scriptures, 60–3. ‘Chaldean’ (like most other names used for different churches and groups in this region) is a problematic term which has been used in numerous different ways historically: for discussion see, for example, John Joseph, The Modern Assyrians of the Middle East: Encounters with Western Christian Missions, Archaeologists, and Colonial Powers (Leiden, 2000), ch. 1; Lucy Parker, ‘Yawsep I of Amida and the Invention of the Chaldeans’, in Bernard Heyberger (ed.), Les Chrétiens de tradition syriaque à l’époque ottomane (Études syriaques 17, Paris, 2020).

As described in notes in CCM 438, fo. 3r, and CCM 338, fo. 207r. On ʿAbd al-Aḥad’s career, see also Wilmshurst, Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 52.

Simon Ditchfield, ‘Decentering the Catholic Reformation: Papacy and Peoples in the Early Modern World’, Archiv für Reformationsgeschichte, ci (2010), though contrast for some nuance, Simon Ditchfield, ‘ “One World Is Not Enough”: The “Myth” of Roman Catholicism as a “World Religion” ’, in Simone Maghenazi and Stefano Villani (eds.), British Protestant Missions and the Conversion of Europe, 1600–1900 (London, 2020), ch. 1.

As noted by Robert Maryks in his review of Ronnie Po-Chia Hsia (ed.), A Companion to Early Modern Catholic Global Missions (Leiden, 2018) — in Renaissance Quarterly, lxxii, no. 4 (2019). The titles of collections on extra-European Catholicism normally prioritize missions and missionaries, as with Po-Chia Hsia (ed.), Early Modern Catholic Global Missions; Nadine Amsler et al. (eds.), Catholic Missionaries in Early Modern Asia: Patterns of Localization (London, 2019); Alison Forrestal and Seán Alexander Smith (eds.), The Frontiers of Mission: Perspectives on Early Modern Missionary Catholicism (Leiden, 2016).