Abstract

The petrographic composition of Cretaceous-age coals hosted in the Benue Trough, Nigeria is presented and discussed in terms of the paleodepositional settings that influenced the coal-bearing formations. The Benue Trough is a failed arm of the triple junction of an inland sedimentary basin that extends in a NE-SW direction from the Gulf of Guinea in the south, to the Chad Basin in the north. A total of twenty-nine (29) coal samples were obtained from nineteen coal localities in the Upper (UBT), Middle (MBT), and Lower Benue Trough (LBT). The high average volatile matter yield, low average ash yield, high calorific value (24.82 MJ/kg, on average), and low sulphur values indicate good quality coal deposits. The organic matter is dominated by vitrinite, reported at an average of 59.3% by volume (mineral-matter free). Variation was noted in the inertinite content across three sub-regions. Liptinite macerals were not commonly observed in the studied samples and were absent in the MBT samples. Coal facies studies decipher the paleoenvironmental conditions under which the vegetation accumulated. Indices commonly used are the gelification index (GI), tissue preservation index (TPI), ground water index (GWI and variations), vegetation index (VI), and wood index (WI). Comparing the array of coal facies models applied, the MBT samples differ from the UBT and LBT samples, concurring with the coal quality data. The UBT and LBT coals formed in an upper deltaic to drier piedmont plane depositional environment, while the MBT coal formed in a lower deltaic marsh to wet forest swamp depositional environment. All samples indicate an ombrotrophic paleomire. In view of the modified equations and the plots used, interpreting depositional environments from just a single model is not reliable.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Coal deposits, a result of the accumulation of vegetation in mires, peat swamps and bogs, can be used to decipher coal forming depositional environments. In order to reconstruct the paleoenvironment of a coal deposit, the primary genetic characteristics of the coal should be studied (Misz-Kennan and Fabiańska 2011; O’Keefe et al. 2013; Dai et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2020). Some of the features required to assess the paleoenvironments of precursor peats include the primary constituents of the coals, such as macerals and minerals and their associations (microlithotypes) (Cornelissen et al. 2004; Silva and Kalkreuth 2005; Misz-Kennan and Fabiańska 2011). Hence, the petrographic assessment of coal macerals can be used to gain an understanding of the conditions that prevailed during peat formation and subsequent coalification. Coal facies studies can decipher the paleoenvironmental conditions under which the vegetation accumulated, as presented by many scholars including Diessel (1982, 1986, 1992), Styan and Bustin (1983), Calder et al. (1991), Taylor et al. (1998), Sahay (2011), Ogala et al. (2012) and Zeiger and Littke (2019). The indices commonly used are the gelification index (GI), tissue preservation index (TPI), ground water index (GWI), vegetation index (VI), and wood index (WI). Dai et al. (2020) raise some concerns as to the use of GI and TPI indices to deduce the mire condition depending on which formulae is applied and to which samples the models are applied. Nonetheless, the various models do provide some insight into palaeoenvironments. Building on the original TPI and GI equations used by Diessel (1982, 1986) and Sahay (2011) included liptinite macerals in the equations. Calder et al. (1991), to calculate the GWI, included mineral matter, and Stock et al. (2016) modified the equation by replacing the mineral matter determined through petrography with the ash yield from proximate analysis.

The current study unpacks the petrographic composition and makes use of complementary geochemical data to interpret the paleodepositional setting prevailing during peatification in the Benue Trough, Nigeria, making use of various coal facies models. The petrographic composition of coal samples reveals the complexity of coal in terms of its discrete microscopic organic (maceral) and inorganic (mineral) components, and their relationships. Chemical data (ash and volatile matter) and gross calorific value (GCV) constitute the basis of many coal purchasing and performance prediction indices; certain parameters are a result of the depositional environment, others due to the coalification process.

2 Geological background

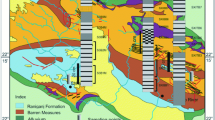

The Benue Trough is an inland sedimentary basin that stretches NNE-SSW, and extends 800 km in length and 150 km in width (Kogbe 1976; Offodile 1976; Ajayi and Ajakaiye 1981; Peters and Ekweozor 1982; Ojoh 1992; Akande et al. 2012) (Fig. 1). The sediments in the Benue Trough are Cretaceous-Cenozoic in age and form part of the Central West Africa Rift System, including Niger, Chad, Cameroon, and Sudan (Burke and Whiteman 1973; Schull 1988; Genik 1993). Many episodes of tectonic events are noted in the basement fragmentation, block faulting, subsidence and rifting systems resulted from the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean. The series of rift basins in the Benue Trough accumulate thick sediments ranging between 4000 and 6000 m (Ajayi and Ajakaiye 1981). Geographically subdivided into the Upper Benue Trough (UBT), Middle Benue Trough (MBT), and Lower Benue Trough (LBT), the geology of the Benue Trough has been extensively investigated by many scholars including Carter et al. (1963); Cratchley (1965); Grant (1971); Kogbe (1976); Offodile (1976); Reyment and Mörner (1977); Petters (1978); Ofoegbu (1988); Schull (1988); Ajibade and Wright (1989); Obaje et al. (1998); and Ogala et al. (2012). The stratigraphic sequence of the Benue Trough is described in Table 1.

The UBT is divided at its northeastern end into the Gongola and Yola sub = basins. In both basins, the Albian Bima Sandstone lies uncomformably on the basement and is overlaid by the Cenomanian transitional/coastal Yolde Formation, representing the beginning of a marine incursion into the UBT (Kogbe 1976; Offodile 1976; Obaje et al. 1998). The Gombe Formation hosts the coal seams in the Gongola Basin, lying conformably on the Yolde Formation. The Gombe Sandstone (Maastrichtian) hosts sediments containing the coal bearing seams (Obaje et al. 1998; Jauro et al. 2007).

In the Yola Basin, the Dukul, Jessu, and Sekuliye Formations, along with the Numanha Shale and the coal bearing Lamja Sandstone, are the upper Cenomanian–Turonian-Santonian equivalents of the Gongola and Pindiga Formations (Kogbe 1976; Offodile 1976). The upper Cenomanian–Turonian-Santonian deposits in the Yola Basin are lithologically and paleo-environmentally similar to those in the Gongola Basin, except the Lamja Sandstone, which has a dominant marine sandstone lithology (Obaje et al. 1998; Jauro et al. 2007). The mid-Santonian was a period of folding and deformation throughout the Benue Trough (Obaje et al. 1998; Jauro et al. 2007).

The MBT basin is not sub-divided as in the case of the UBT and the LBT. The Precambrian Basement is overlain by the Asu River Group, which consists of the Arufu, Uomba, and Awe Formations (Ofoegbu 1985). The Asu River Group is overlain by the Ezeaku, Keana/Awe, and Awgu Formations. The Awgu Formation consists of shale/sandstones which host the coal deposits and is overlain by the Lafia Formation belonging to the Turonian-Santonian depositional cycle (Kogbe 1976; Offodile 1976; Obaje et al. 1998). The MBT is noted for its dynamic geologic history and fracture systems that are associated with igneous intrusions (Moshood 2004).

The LBT is divided into the Anambra Basin and Abakaliki Syncline which were formed in the late Cretaceous Period. They are associated with the separation of the African and South American continents and the subsequent opening of the South Atlantic Ocean (Murat 1972; Obaje et al. 1998; Ogala et al. 2012). During the filling of the Benue-Abakaliki sector of the Trough in Albian-Santonian times, the proto-Anambra Basin was a platform (Murat 1972; Benkhelil 1989; Obaje et al. 1998; Ogala et al. 2012). The Anambra Basin contains 6 km of sedimentary sequences of Cretaceous age and is the structural link between the Cretaceous Benue Trough and the Cenozoic Niger Delta (Mohammed 2005). Slow subsidence followed by a regression in Maastrichtian times, during which deltaic forests and floodplain developed, resulted in the coal measures of the Mamu, Ajali and Nsukka Formations; Awgu Formation and the Agbani sandstone; and the Odukpani Formation and Agala sandstone (Obaje et al. 1998; Ogala et al. 2012).

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Sampling

Twenty-nine (29) grab coal samples (Table 2), sampled at depths ranging from 1 to 3 m, were obtained from nineteen coal localities (Fig. 2) (seven samples from UBT, nine from the MBT, and thirteen from the LBT). Each sample had a mass between 2 and 5 kg. Samples originated from surface excavations where various seams outcropped; the excavations included active mines, borehole cuttings, river cuttings (weathered surfaces were removed prior to sampling), and an old mine shaft. Access to sample localities was a challenge, in view of persistent attacks by Boko Haram terrorists and Fulani herdsmen, and sampling may not have been optimised. However, the samples do provide adequate opportunity to gain an understanding of coal from the Benue Trough.

3.2 Sample preparation

The coal samples were milled to − 1 mm at the School of Chemical and Metallurgy Engineering Coal Laboratory, University of the Witwatersrand (Wits). Each sample was split for petrography (approximately 50 g) and the remainder milled to 212 μm for chemical analyses, elemental, and mineral composition. The data pertaining to the mineralogy and geochemistry of the coal samples will be reported in subsequent publications. For coal petrography, the particles were mixed with epoxy resin and hardener, and moulded as 30-mm-diameter block mounts. Each block surface was ground and polished for petrographic analysis in line with ISO 7404-2:2015, using a Struers Tegra-Force polisher with a final polish of 0.04-μm colloidal silica.

3.3 Complementary analyses

Proximate analysis was performed at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) using a Perkin Elmer Thermogravimetric Analyzer following the procedure of ASTM D3172-13 (2013). Ultimate analysis was undertaken at Bureau Veritas, Centurion, South Africa, following SANS 17247 (2006) and ISO 17247 (2005). Gross calorific value was determined using a dry-cal bomb calorimeter at Wits (SANS 1928, 2009).

3.4 Petrographic analyses

The maceral, microlithotype, and vitrinite reflectance analyses were performed according to standard procedures: SANS/ISO 7404-3 2016; SANS/ISO 7404-4 2018; SANS/ISO 7404-5 2016, respectively. The study followed the terminology recommended by the International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology (ICCP) (ICCP 1998, 2001; Pickel et al. 2017). The point count method for maceral and microlithotype determination was conducted on the polished grain mount blocks under oil-immersion with a × 50 oil-immersion objective (total magnification of × 500) using a semi- automated point-counting stage on a Zeiss Axio Imager M2m reflected light microscope retrofitted with Hilgers Fossil Diskus components and software, housed at the University of Johannesburg (UJ). A minimum of 500 readings were recorded for the maceral and microlithotype analyses. Mean random vitrinite reflectance (% RoVmr) measurements were carried out on the polished blocks following calibration using two glass reflectance standards with known reflectance values: a five-block standard with reflectance values 0.31, 0.50, 0.92, 0.99, and 1.63, and an Yttrium–Aluminium Gallium YAG (% Ro = 0.90 and zero reflectance). The calibration was checked between each sample, and a minimum of 100 readings were taken on collotelinite, avoiding poorly polished or pitted vitrinite. Coal rank is not related to the palaeoenvironment at the time of peatification but is included herein for completeness in terms of the petrographic analyses.

4 Results

4.1 Complementary analyses

The proximate and ultimate data are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3. The relatively low ash yields observed in the LBT samples agree with data presented by Ogala et al. (2012). The GCV values for the UBT and LBT samples are higher than those for the MBT samples, representing higher grade coals. The moisture content was higher in some of the coal samples, possibly indicative of variable coal rank, or a degree of weathering due to the sample origin (grab surface samples). Samples 01 and 17 had very high ash yields, 69.2% and 79.0%, respectively. These samples were omitted from the average calculations in Table 3, as they were not considered to be coal (ISO11760 2005). The sulphur content was generally less than 1%, except for a few samples (16, 17, 04, 08 18 and 20) where values above 1% were determined (Table 3). The sulphur data agrees with the findings by Ogala et al. (2012), but some variation is noted with data provided by Ayinla et al. (2017). Sample 16 was taken from the B Seam in the Maiganga coal mine and has a very high sulphur value, differing from the far lower sulphur values reported by Ayinla et al (2017). It may be that the grab sample in this study intersected a pyrite vein or large nodule. Despite being grab samples, proximate and ultimate data indicated that the samples generally represented coals of high quality (ISO 11760 2019).

4.2 Vitrinite reflectance

Variation was observed in the coal rank from the three sub-regions of the Benue Trough (Table 4). The reflectance values, on average, placed the UBT samples in the medium rank D bituminous coal category (ISO 11760 2019). The LBT samples fell in the low rank A subbituminous category, and the MBT samples as medium rank C bituminous coals (Table 4), except for sample 09 which was classified as lignite. Samples 01 – 07 are from the same locality but different coal seams, sampled along a river channel (River Dep), represented as horizons A–G (Table 2); no weathering effect was determined. Three locations in the UBT contain coals in the medium rank C category, but all samples in the LBT region were low rank, implying differing coalification processes between the three sub-basins. Owing to the variations in coal rank reported, the study included the maceral terminology recommended by the ICCP for huminite (ICCP 2001; Sýkorová et al. 2005; ICCP 1998, 2001; Pickel et al. 2017).

4.3 Maceral and mineral composition

The maceral composition varies through the sub-regions of the Benue Trough, as shown in Fig. 3 and Tables 5, 6, 7. The samples showed dominance in vitrinite, with varying proportions of the inertinite and liptinite. Liptinite was poorly distributed in the UBT and LBT samples, and generally missing in the MBT except for sample 09 that shows a higher liptinite content. Samples from both the UBT and LBT contained funginite, which was absent in the MBT samples. These findings imply different peatification conditions prevailed in the MBT compared to the LBT and UBT, indicative of variable geological controls during the Cretaceous to early Cenozoic. Resinite is the dominant liptinite maceral, collodetrinite the dominant vitrinite maceral, and fusinite the dominant inertinite maceral.

Five of the coal samples (15, 16, 09, 28, 29) were classified as lignite (Table 4). These were described using the huminite classification system (Sýkorová et al. 2005; ISO 7404-5 2009) for adherence to petrographic norms and were also described using the classification for bituminous coal for ease of comparison with the other samples of the study (Table 8). The LBT samples were dominated by densinite, equivalent to collodetrinite in higher rank coals. Note that collodetrinite is also the dominant maceral in the higher rank coal samples (Tables 5, 6, 7).

The observable mineral matter showed a similar trend to the ash yield, with the MBT samples containing the highest mineral matter compared to the UBT and LBT samples. The dominant minerals observed were clays and quartz, with limited pyrite in the LBT samples. Detrital zircons were observed in the MBT samples studied, but further study is required for confirmation. As with the maceral composition, the observable mineral composition indicates different geological controls and even sediment source in the MBT compared to the two other sub-regions (Fig. 4).

Selection of macerals observed (× 500, scale-bar is 100 µm; oil immersion, reflected light) (UBT: A–D; MBT: E–H and LBT: I–L). Note: (QTZ: Quartz; FUS: Fusinite; TEL:Telinite; GEL: Gelinite; RES: Resinite; CUT: Cutinite; FUG: Funginite; CD; Collodetrinite; PY: Pyrite (framboidal structure); COR: Corpogelinite)

4.4 Microlithotype composition

The microlithotype composition is plotted in Fig. 5 and shown in Table 9. Vitrite was dominant in most of the samples. The MBT samples were primarily vitrite-rich, whereas the UBT and the LBT samples showed varied composition. Duroclarite was abundant in UBT and LBT samples and was apparently absent in the MBT samples. Clarodurite and vitrinertoliptite were poorly distributed in the UBT and LBT samples. Carbominerite in the samples was dominated by carbargillite/clays and carbosilicate/quartz (Table 9). Sample 16 (UBT, B seam, Gombe Formation) has a high carbopyrite content, indicating an area of high sulphur. The total sulphur for this sample is 7.34%, far higher than the other 28 samples.

5 Discussion

Qualitative and quantitative petrographic data are used to unpack the paleodepositional history of the coal deposits in the Benue Trough. The data is useful in understanding the coal facies and depositional controls of the peat swamp. The maceral data plotted on the coal facies diagram (Fig. 6) shows that 70% of the samples cluster in the lacustrine environment with 25% in the fluvial environment. All the MBT samples plot in the lacustrine environment, in contrast to UBT and LBT samples (Fig. 6). Four of the UBT samples (13, 14, 15, and 16) represent a stratigraphic sedimentary sequence where sample 13 is the topmost sample followed by samples 14 to 16. Samples 13 and 14 cluster in the lower deltaic facies field, while samples 15 and 16 plot in the fluvial setting field. Samples 15 and 16 were noted for high proportion of fusinite fragments that were possibly generated by forest fire and blown into the peat swamp. This affects the reliability of the plots as the fusinite may not have been derived in situ.

Coal facies diagram proposed for the coal studied (samples 01 and 17 are excluded), modified after Teichmüller (1989)

Most models used in coal facies analysis are the TPI, GI, GWI, and VI (Diessel 1986), which are based on quantitative amounts of coal constituents including macerals to determine paleoenvironments. Diessel (1986) developed these models for Permian coals of the Hunter Valley, NSW, Australia; the models may not be applicable to all coals globally. TPI and GI have been more widely used to infer peat depositional environment than the GWI and VI; all indices have some shortcomings as discussed by Dai et al. (2020). In order to interpret the depositional environments for these coal samples, GI and TPI equations were considered for the facies studies as proposed by other scholars, namely: Diessel (1986), Calder et al. (1991), Müller et al. (1992), Silva and Kalkreuth (2005), Sahay (2011), and Stock et al. (2016). The TPI and GI values were calculated using the formulae expressed by Diessel (1986) in Eqs. (1) and (2) and were further modified by Silva and Kalkreuth (2005). Sahay (2011) modified the indices to include liptinite as expressed in Eqs. (3) and (4).

Calder et al. (1991) considered the groundwater, vegetation, and wood indexes as expressed in Eqs. (5), (6), and (7); while Stock et al. (2016) included the ash yield divided by 2 as expressed in Eqs. (8) and (9) used by Zieger and Littke (2019). Stock et al. (2016) modified the GWI equation of Calder et al. (1991) by considering the ash yield divided by 2 as seen in Eq. (8).

TPI and GI according to Sahay (2011) modified equation.

The coal facies model based on Diessel (1986), modified after Silva and Kalkreuth (2005), and Sayay (2011) formulae are plotted in Figs. 7 and 8. Variation was noted in the TPI and GI values based on the Diessel (1986) and Sahay (2011) formulae, due to limited liptinite macerals especially in the MBT region. TPI values are low for the coal samples suggesting a predominance of herbaceous plant in the mire or large-scale destruction of wood because of extensive humification and mineralization (Diessel 1992). However, a few samples are noted with high TPI values indicative of the non-destruction of the wood (well preserved plant material). Samples 15 and 26 plot out of Fig. 7, indicating this model does not fit all samples; these samples have very high fusinite contents. Samples 15 and 26 plot into Fig. 8 and the clustering of the samples appears better using the modified equations proposed by Sayah (2011).

The MBT samples are noted for high GI values, suggesting a high moisture content in the mire with higher rate of subsidence and a decrease in oxidation (Table 10). However, few of the UBT and LBT samples showed similarity in high GI values (Table 10). Based on the tree density coal facies diagram and using Sahay (2011) formula, the plots showed a positive tree density (Fig. 8), while Diessel (1986) formula showed greater variation in distribution (Fig. 7; Table 10).

The UBT and LBT samples reveal a transitional paleoenvironment ranging from transgressive and regressive, upper-deltaic to drier piedmont plane, related to their vitrinite-rich content with variability in inertinite content (Fig. 8). A gradual change in vegetation type and subsidence rates of the palaeomire affect maceral accumulation. The MBT samples cluster in the marsh to wet forest facies.

The paleomire conditions varied from (borderline) ombrotrophic (atmospheric/rain moisture) limnic environment to mesotrophic (most samples) to (borderline) rheotrophic hydrological conditions (surface water) as shown in Fig. 9. The clustering of all the Benue Trough samples is improved in Fig. 10, with all samples plotting to mesotrophic to borderline ombrotrophic peat mires. Mesotrophic mires are characteristic of a moderate amount of dissolved nutrients in the body of water. Samples 15, 26, and 16 (all very high in fusinite) indicate very high vegetation index values; all other samples plot under 2.

Teichmüller (1989) observed that wet conditions of peat formation are normally distinguished by high GI and high TPI indices for wet conditions, while low GI and low TPI indices are distinguished by dry conditions. TPI values for the studied coal samples are generally low suggesting either a predominance of herbaceous plant in the mire or large-scale destruction of wood due extensive humification and mineralization (Diessel 1992). However, some samples are noted for high TPI values due to non-destruction of the wood (well preserved plant material). Despite the distinct geographical regions and different coal seams most samples show similar depositional settings based on the TPI and GI values (Figs. 8 and 10; Table 10).

Coal is heterogeneous in composition and, likewise, the coal samples from the Benue Trough are characterized by different qualities because of the depositional environments. Akinyemi et al. (2020) found comparable results. The UBT samples showed varied depositional setting (back barrier to wet forest swamp to terrestrial environment) which influenced the maceral distribution. The MBT coal deposits (marsh to lower delta plain) developed in a wet condition as indicted by the high vitrinite and higher mineral matter content (compared to the UBT and LBT samples); these MBT samples contained very little fusinite. LBT and UBT samples ranged from limnic—back barrier—wet/dry forest swamp—terrestrial environment in a wet to dry environment.

Samples 15, 16 (UBT), 18, and 26 (LBT) (refer to Fig. 2 for location) were noted for high TPI and VI, with low GI. These samples contain higher amounts of inertinite, an indication of dry palaeomire conditions. Samples 15, 16, and 26 have very high fusinite contents, which is likely to have affected the reliability of the facies model equations. This fusinite is unlikely to have formed in situ (refer to the low fusite values in Table 9) and more likely blown into the palaeomire, as indicated by the fragmented nature of the fusinite particles. The fact that the MBT samples have very little fusinite is again of interest. The high TPI values indicated a balanced ratio of plant growth and peat accumulation with a rise in the water level due to basin subsidence.

6 Conclusions

The study presented the detailed petrographic composition of twenty-nine grab samples taken from the three sub-basins of the Benue Trough, Nigeria. The depositional conditions that influenced the coal-bearing formations hosted within the Benue Trough were discussed using a variety of facies models. The entire sedimentary package within the Benue Trough occurs in a failed arm of the triple junction, an inland sedimentary basin that influenced the vegetation accumulation, and subsequent coalification and coal quality. It is evident from the maceral data that the geological structure of the trough impacted on the depositional environment, with the MBT samples forming in a different paleoenvironment to the UBT and LBT samples.

The chemical results show high GCV (24.82 MJ/kg average), low ash yield, and low sulphur content (0.94% on average). The MBT samples are generally noted for their lower GCV (21.97 MJ/kg average) compared to the UBT and LBT samples, where average GCVs of 24.11 and 28.39 MJ/kg, respectively, were recorded.

The petrographic data show a degree of variation in maceral composition between the three sub-regions of the Benue Trough. The coal samples are generally medium vitrinite (average composition of 59.3% by volume (mmf)), with variability in inertinite and liptinite distribution. Liptinite macerals occur in the UBT and LBT samples but are conspicuously absent in the MBT sub-region. The MBT samples have higher vitrinite reflectance values—a consequence of coalification not the depositional environment. The variation in petrographic properties is indicative of differing syn-and post-depositional influences in the MBT compared to those imposed on the UBT and LBT. Akinyeme et al. (2020) also report high vitrinite with variable inertinite contents.

The coal facies model plots indicate that UBT and LBT coals formed in an upper deltaic to drier piedmont plane depositional environment, while the MBT coal formed in a lower deltaic marsh to wet forest swamp depositional environment. Ayinla et al (2017) also concluded that the UBT Gombe Formation Maigonya coals formed in an upper deltaic plane. Using GWIac and VI (Eqs. (8) and (9), all the samples fall in a mesotrophic hydrological environment following the equations of Stock et al. (2016). Coal samples in the MBT region are generally characterized by high GI, indicative of a wet environment. Most of the coal samples plot within the lower delta plain to dry forest swamp/wet forest swamp to terrestrial in the telmatic (tree density positive) depositional environment.

In view of the modified equations and the plots used, interpreting depositional environment accurately from just a single model is quite challenging. Therefore, a combination of published models based on the petrographic indices is highly recommended. Not all facies models are applicable to all coals globally.

References

Ajayi C, Ajakaiye D (1981) The origin and peculiarities of the Nigerian Benue Trough: another looks from recent gravity data obtained from the Middle Benue. Tectonophysics 80:285–303

Ajibade A, Wright J (1989) The Togo-Benin-Nigeria Shield: evidence of crustal aggregation in the Pan-African belt. Tectonophysics 165:125–129

Akande SO, Egenhoff SO, Obaje NG, Ojo OJ, Adekeye OA, Erdtmann BD (2012) Hydrocarbon potential of Cretaceous sediments in the Lower and Middle Benue Trough, Nigeria: Insights from new source rock facies evaluation. J Afr Earth Sci 64:34–47

Ayinla HA, Abdullah WH, Makeen YM, Abubakar MB, Jauro A, Yandoka BMS, Abidin NSZ (2017) Petrographic and geochemical characterization of the Upper Cretaceous coal and mudstones of Gombe Formation, Gongola sub-basin, northern Benue trough Nigeria: implications for organic matter preservation, palaeodepositional environment and tectonic settings. Int J Coal Geol 180:67–82

Akinyemi SA, Adebayo OF, Nyakuma BB, Adegoke AK, Aturamu OA, OlaOlorun OA, Adetunji A, Hower JC, Hood MM, Jauro A (2020) Petrology, physicochemical and thermal analyses of selected cretaceous coals from the Benue Trough Basin in Nigeria. Int J Coal Sci Technol 7:26–42

ASTM D3172-13 (2013) Standard practice for proximate analysis of coal and coke. ASTM International, West Conshohocken

Benkhelil J (1989) The origin and evolution of the Cretaceous Benue Trough (Nigeria). J Afr Earth Sci (and the Middle East) 8:251–282

Burke K, Whiteman A (1973) Uplift, rifting and the break-up of Africa. Implic Cont Drift Earth Sci 2:735–755

Calder J, Gibling M, Mukhopadhyay P (1991) Peat formation in a Westphalian B piedmont setting, Cumberland basin, Nova Scotia: Implications for the maceral-based interpretation of rheotrophic and raised paleomire. Contribution series No. 91-002

Carter J, Barber W, Tait E, Jones G (1963) The geology of parts of Adamawa. Bauchi and Bornu provinces in northeastern Nigeria. Geol Surv Nig Bull 30:1–109

Cornelissen G, Kukulska Z, Kalaitzidis S, Christanis K, Gustafsson Ö (2004) Relations between environmental black carbon sorption and geochemical sorbent characteristics. Environ Sci Technol 38:3632–3640

Cratchley CR (1965) An interpretation of the geology and gravity anomalies of the Benue Valley, Nigeria. Overseas Geol Surv Geophys 1:26

Dai S, Bechtel A, Eble CF, Flores RM, French D, Graham IT, Hood M, Hower JC, Korasidis VA, Moore TA, Püttmann W, Qi We, Zhao L, O’Keefe JMK (2020) Recognition of peat depositional environments in coal: a review. Int J Coal Geol 219:103383

Diessel CFK (1982) An appraisal of coal facies based on maceral characteristics. Aust Coal Geol 4(2):474–484

Diessel CFK (1986) On the correlation between coal facies and depositional environments. In: Proceeding 20th Symposium of Department Geology, University of New Castle, New South Wales, pp 19–22

Diessel CFK (1992) Coal-bearing depositional systems. Springer, Berlin, p 721

Ehinola O (1995) Facies evolution of the middle Cretaceous black shales from the Lower Benue Trough, SE Nigeria. Unpublished MSc dissertation. (Ibadan: University of Ibadan), p 21

Genik G (1993) Petroleum geology of Cretaceous-Tertiary rift basins in Niger, Chad, and Central African Republic. AAPG Bull 77:1405–1434

Grant NK (1971) South Atlantic, Benue Trough, and Gulf of Guinea Cretaceous Triple Junction. Geol Soc Am Bull 82:2295–2298

ICCP (International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology) (1998) The new vitrinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 80(4):459–471

ICCP (International Committee for Coal and Organic Petrology) (2001) The new inertinite classification (ICCP System 1994). Fuel 77(5):349–358

ISO 7404-3 (2017) Methods for the petrographic analysis of coal—part 4: method of determining microlithotype, carbominerite and minerite composition. ISO, Geneva

ISO 7404-2 (2009) Methods for the petrographic analysis of coal—part 2: preparation of coal samples. ISO, Geneva

ISO 7404-5 (2009) Methods for the petrographic analysis of coal—part 5: method of determining microscopically the reflectance of vitrinite. ISO, Geneva

ISO 11760 (2019) Classification of coals. ISO, Geneva

Jauro A, Obaje N, Agho M, Abubakar M, Tukur A (2007) Organic geochemistry of Cretaceous Lamza and Chikila coals, upper Benue trough, Nigeria. Fuel 86:520–532

Kogbe CA (1976) Geology of Nigeria. Elizabethan Publishing Company, Lagos, pp 237–252

Liu B, Zhao C, Fiebig J, Bechtel A, Sun Y, Püttmann W (2020) Stable isotopic and elemental characteristics of pale and dark layers in a late Pliocene lignite deposit basin in Yunnan Province, southwestern China: implications for paleoenvironmental changes. Int J Coal Geol 226:103498

Misz-Kennan M, Fabiańska MJ (2011) Application of organic petrology and geochemistry to coal waste studies. Int J Coal Geol 88:1–23

Mohammed Y (2005) Predictive petroleum system model of prospective Anambra Basin, Nigeria. Nigerian Association of Petroleum Explorationists. American Association of Petroleum Geologists Abstracts (NAPE/AAPG) Publication, p 70.

Moshood NT (2004) Evolution of saline waters and brines in the Benue Trough, Nigeria. Appl Geochem 19:1355–1365

Müller G, Diessel E, Weiss D, Von Klitzing K, Ploog K, Nickel H, Schlapp W, Lösch R (1992) Influence of interedge channel scattering on the magneto-transport of 2D-systems. Surf Sci 263:280–283

Murat R (1972) Stratigraphy and paleogeography of the Cretaceous and Lower Tertiary in southern Nigeria. Afr Geol 1:251–266

Obaje NG (2009) Geology and mineral resources of Nigeria. Springer, Berlin, p 221p

Obaje NG, Abaa SI, Funtua II, Ligouis B (1998) Organic maturation and coal-derived hydrocarbon potentials of Cretaceous coal measures in the middle Benue Trough of Nigeria. J Min Geol 34(1):7–18

Obaje N, Abaa S, Najime T, Suh C (1999) Economic geology of Nigerian coal resources—a brief review. Afr Geosci Rev 6:71–82

Offodile ME (1976) The geology of the middle Benue, Nigeria. Palaentological Inst Univ Uppsala Spec Publ 4:1–166

Ofoegbu CO (1984) A model for the tectonic evolution of the Benue Trough of Nigeria. Geol Rundsch 73(3):1007–1018

Ofoegbu CO (1985) A review of the geology of the Benue Trough, Nigeria. J Afr Earth Sci (1983) 3:283–291

Ofoegbu C (1988) An aeromagnetic study of path of the Upper Benue Trough, Nigeria. J Afr Earth Sci (and the Middle East) 7:77–90

Ogala J, Siavalas G, Christanis K (2012) Coal petrography, mineralogy and geochemistry of lignite samples from the Ogwashi-Asaba Formation, Nigeria. J Afr Earth Sci 66:35–45

Ojoh K (1992) The Southern part of the Benue Trough (Nigeria) Cretaceous stratigraphy, basin analysis, paleo-oceanography and geodynamic evolution in the equatorial domain of the South Atlantic. NAPE Bull 7:67–74

O’Keefe JM, Bechtel A, Christanis K, Dai S, Dimichele WA, Eble CF, Esterle JS, Mastalerz M, Raymond AL, Valentim BV, Wagner NJ (2013) On the fundamental difference between coal rank and coal type. Int J Coal Geol 118:58–87

Petters S (1978) Stratigraphic evolution of the Benue Trough and its implications for the Upper Cretaceous paleogeography of West Africa. J Geol 86:311–322

Petters SW, Ekweozor CM (1982) Origin of mid-cretaceous black shales in the Benue Trough, Nigeria. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 40(4):311–319

Pickel W, Kus J, Flores D, Kalaitzidis S, Christanis K, Cardott BJ, Misz-Kennan M, Rodrigues S, Hentschel A, Hamor-Vido M, Crosdale P (2017) Classification of liptinite—ICCP System 1994. Int J Coal Geol 169:40–61

Reyment R, Mörner N (1977) Cretaceous transgressions and regressions exemplified by the South Atlantic. Spec Pap Palaeont Soc Jpn 21:247–261

Sahay V (2011) Limitation of petrographic indices in depositional environmental interpretation of coal deposits. Open Geosci 3:287–290

SANS 1928:2009/ISO 1928 (2009) Solid mineral fuels—determination of gross calorific value by the bomb calorific method, and calculation of net calorific value

SANS 17247:2006/ISO 17247 (2005) Coal-ultimate analysis

Schull TJ (1988) Rift basins of interior Sudan: petroleum exploration and discovery. AAPG Bull 72:1128–1142

Silva M, Kalkreuth W (2005) Petrological and geochemical characterization of Candiota coal seams, Brazil—implication for coal facies interpretations and coal rank. Int J Coal Geol 64:217–238

Stock AT, Littke R, Lücke A, Zieger L, Thielemann T (2016) Miocene depositional environment and climate in western Europe: the lignite deposits of the Lower Rhine Basin, Germany. Int J Coal Geol 157:2–18

Styan WT, Bustin R (1983) Petrography of some fraser river delta peat deposits: coal maceral and microlithotype precursors in temperate-climate peats. Int J Coal Geol 2:321–370

Sýkorová I, Pickel W, Christanis K, Wolf M, Taylor G, Flores D (2005) Classification of huminite—ICCP System 1994. Int J Coal Geol 62:85–106

Taylor GH, Teichmüller M, Davis A, Diessel C, Littke R, Robert P (1998) Organic petrology. Gebrüder Borntraeger, Berlin, p 704

Teichmüller M (1989) The genesis of coal from the viewpoint of coal petrology. Int J Coal Geol 12(1–4):1–87

Zieger L, Littke R (2019) Bolsovian (Pennsylvanian) tropical peat depositional environments: the example of the Ruhr Basin, Germany. Int J Coal Geol 211:103209

Acknowledgements

The support of the Department of Science and Innovation through its funding agency, the National Research Foundation, and the Centre of Excellence for Integrated Mineral and Energy Resource Analysis (DSI-NRF CIMERA) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author(s) and are not necessarily to be attributed to the CoE, DSI or NRF. The authors would like to thank DSI-NRF CIMERA for financial support during the PhD studies. Special appreciation goes to the University of Johannesburg Geology Department for access to the petrographic microscope and other analytical facilities, and the University of the Witwatersrand for allowing access to the Coal and Gemin Laboratories for general coal characterisation analyses. I remain forever grateful to University of Jos-Nigeria for releasing me for this study on coal petrology. I thank Dr Jessica Atong Pinta for editing the paper. I thank Mr Ajol Fube for assisting in sample collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAD wrote this article as an extract from the thesis in partial fulfillment of his PhD programme at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa, under the supervision of Prof. NJW and co-supervised by Prof. UAL. Prof. NJW assisted with funding, training, guidance of the research, and construction and editing of this manuscript. Dr. MOM provided contributions to the design of the work and gave extensive suggestions on the data analysis and interpretation and editing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mangs, A.D., Wagner, N.J., Moroeng, O.M. et al. Petrographic composition of coal within the Benue Trough, Nigeria and a consideration of the paleodepositional setting. Int J Coal Sci Technol 9, 35 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00500-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40789-022-00500-5